The Cell Polarity Protein Scribble Is Involved in Maintaining the Structure of Neuromuscular Junctions, the Expression of Myosin Heavy Chain Genes, and Endocytic Recycling in Adult Skeletal Muscle Fibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Procedures and Genotyping

2.2. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, PCR

2.3. SDS-PAGE, Western Blot, Immunoprecipitation

2.4. Histochemical Staining, Immunofluorescence Staining, Quantitative 3D Morphometrical Imaging, Color Deconvolution, Fluorescence Microscopy

2.5. Nerve Muscle Preparation and Electrophysiological Recordings

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Muscle Grip Strength Is Reduced in Conditional Muscle-Specific Scribble Knockout Mice

3.2. The Absence of Scribble Did Not Affect ERBIN, Only LANO Protein Levels, but Reduced Interaction of All LAP Proteins with RAB Indicated Involvement in Endocytic Recycling

3.3. Skeletal Muscle in Scribble Mutant Mice Does Not Show Any Changes in General Muscle Histology or Energy Metabolism

3.4. Myosin Heavy Chain Transcript Levels and Cross-Sectional Areas of Skeletal Muscle Fibers Are Altered in Conditional Scribble-Deficient Mice

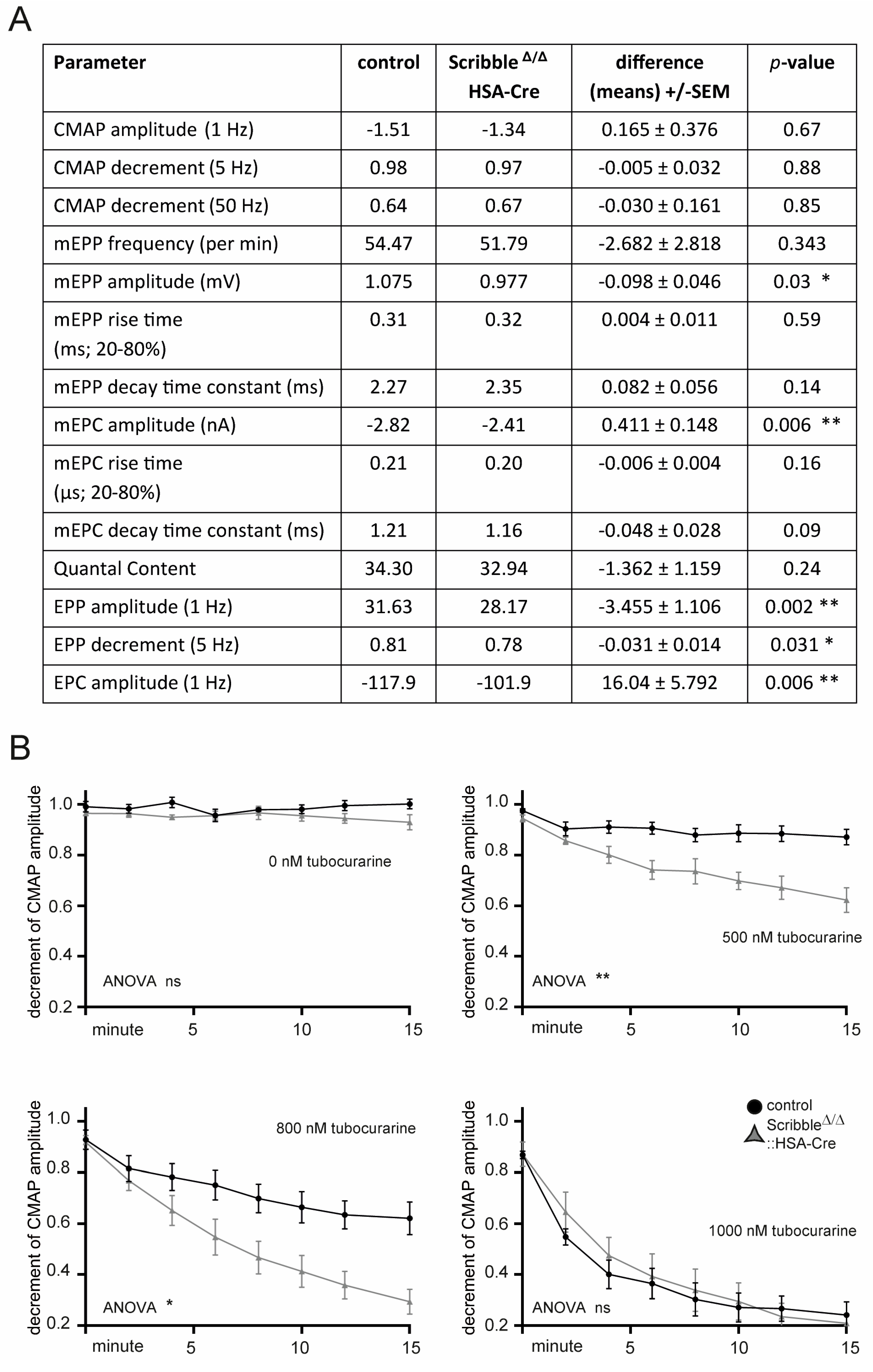

3.5. Neuromuscular Transmission Was Compromised in Skeletal Muscles of Mutant Scribble Mice

3.6. The NMJs of Mutant Scribble Knockout Muscles Are Fragmented, and Less Acetylcholine Receptor Alpha Subunit Is Expressed

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilder, D.; Birnbaum, D.; Borg, J.P.; Bryant, P.; Huigbretse, J.; Jansen, E.; Kennedy, M.B.; Labouesse, M.; Legouis, R.; Mechler, B.; et al. Collective nomenclature for LAP proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, E114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, J.P.; Marchetto, S.; Le Bivic, A.; Ollendorff, V.; Jaulin-Bastard, F.; Saito, H.; Fournier, E.; Adelaide, J.; Margolis, B.; Birnbaum, D. ERBIN: A basolateral PDZ protein that interacts with the mammalian ERBB2/HER2 receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Shen, C.; Luo, S.; Traore, W.; Marchetto, S.; Santoni, M.J.; Xu, L.; Wu, B.; Shi, C.; Mei, J.; et al. Role of Erbin in ErbB2-dependent breast tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4429–E4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Shen, C.; Luo, Z.; Bates, C.R.; Lee, D.; Marchetto, S.; Gao, T.M.; Borg, J.P.; Xiong, W.C.; et al. Erbin interacts with TARP gamma-2 for surface expression of AMPA receptors in cortical interneurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apperson, M.L.; Moon, I.S.; Kennedy, M.B. Characterization of densin-180, a new brain-specific synaptic protein of the O-sialoglycoprotein family. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 6839–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilder, D.; Perrimon, N. Localization of apical epithelial determinants by the basolateral PDZ protein Scribble. Nature 2000, 403, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legouis, R.; Gansmuller, A.; Sookhareea, S.; Bosher, J.M.; Baillie, D.L.; Labouesse, M. LET-413 is a basolateral protein required for the assembly of adherens junctions in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Santoni, M.J.; Arsanto, J.P.; Jaulin-Bastard, F.; Le Bivic, A.; Marchetto, S.; Audebert, S.; Isnardon, D.; Adelaide, J.; Birnbaum, D.; et al. Lano, a novel LAP protein directly connected to MAGUK proteins in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 32051–32055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, J.P.; Sun, T.Y.; Montell, D.J. Development and dynamics of cell polarity at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Wang, Q.; Xiong, W.C.; Mei, L. Erbin is a protein concentrated at postsynaptic membranes that interacts with PSD-95. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 19318–19326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin-Jageman, I.; Yu, K.; Hall, R.A.; Mei, L.; Lee, A. Erbin enhances voltage-dependent facilitation of Ca(v)1.3 Ca2+ channels through relief of an autoinhibitory domain in the Ca(v)1.3 alpha1 subunit. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Tao, Y.; Shen, C.; Tan, Z.; Xiong, W.C.; Mei, L. Erbin is required for myelination in regenerated axons after injury. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 15169–15180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarjour, A.A.; Boyd, A.; Dow, L.E.; Holloway, R.K.; Goebbels, S.; Humbert, P.O.; Williams, A.; ffrench-Constant, C. The polarity protein Scribble regulates myelination and remyelination in the central nervous system. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentzinger, C.F.; Wang, Y.X.; Rudnicki, M.A. Building muscle: Molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a008342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, Y.; Urata, Y.; Goto, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Humbert, P.O.; Li, T.S.; Zammit, P.S. Muscle stem cell fate is controlled by the cell-polarity protein Scrib. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.R.; Lichtman, J.W. Development of the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1999, 22, 389–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Luo, S.; Wang, Q.; Suzuki, T.; Xiong, W.C.; Mei, L. LRP4 serves as a coreceptor of agrin. Neuron 2008, 60, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Stiegler, A.L.; Cameron, T.O.; Hallock, P.T.; Gomez, A.M.; Huang, J.H.; Hubbard, S.R.; Dustin, M.L.; Burden, S.J. Lrp4 is a receptor for Agrin and forms a complex with MuSK. Cell 2008, 135, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherbee, S.D.; Anderson, K.V.; Niswander, L.A. LDL-receptor-related protein 4 is crucial for formation of the neuromuscular junction. Development 2006, 133, 4993–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, D.J.; Bowen, D.C.; Stitt, T.N.; Radziejewski, C.; Bruno, J.; Ryan, T.E.; Gies, D.R.; Shah, S.; Mattsson, K.; Burden, S.J.; et al. Agrin acts via a MuSK receptor complex. Cell 1996, 85, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChiara, T.M.; Bowen, D.C.; Valenzuela, D.M.; Simmons, M.V.; Poueymirou, W.T.; Thomas, S.; Kinetz, E.; Compton, D.L.; Rojas, E.; Park, J.S.; et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo. Cell 1996, 85, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxfield, F.R.; McGraw, T.E. Endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.D.; Donaldson, J.G. Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonsen, A.; Gaullier, J.M.; D’Arrigo, A.; Stenmark, H. The Rab5 effector EEA1 interacts directly with syntaxin-6. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 28857–28860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, E.; Christoforidis, S.; Uttenweiler-Joseph, S.; Miaczynska, M.; Dewitte, F.; Wilm, M.; Hoflack, B.; Zerial, M. Rabenosyn-5, a novel Rab5 effector, is complexed with hVPS45 and recruited to endosomes through a FYVE finger domain. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.H.; Jahnel, M.; Lauer, J.; Avellaneda, M.J.; Brouilly, N.; Cezanne, A.; Morales-Navarrete, H.; Perini, E.D.; Ferguson, C.; Lupas, A.N.; et al. An endosomal tether undergoes an entropic collapse to bring vesicles together. Nature 2016, 537, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Schweinsberg, P.J.; Vashist, S.; Mareiniss, D.P.; Lambie, E.J.; Grant, B.D. RAB-10 is required for endocytic recycling in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, A.; Chen, C.C.; Banerjee, R.; Glodowski, D.; Audhya, A.; Rongo, C.; Grant, B.D. EHBP-1 functions with RAB-10 during endocytic recycling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 2930–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Hang, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, C.; He, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; et al. LET-413/Erbin acts as a RAB-5 effector to promote RAB-10 activation during endocytic recycling. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 217, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piguel, N.H.; Fievre, S.; Blanc, J.M.; Carta, M.; Moreau, M.M.; Moutin, E.; Pinheiro, V.L.; Medina, C.; Ezan, J.; Lasvaux, L.; et al. Scribble1/AP2 complex coordinates NMDA receptor endocytic recycling. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, L.; Straubinger, M.; Khan, M.A.; Nalleweg, N.; Cheusova, T.; Hashemolhosseini, S. Identification of Erbin interlinking MuSK and ErbB2 and its impact on acetylcholine receptor aggregation at the neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 6620–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravic, B.; Huraskin, D.; Frick, A.D.; Jung, J.; Redai, V.; Palmisano, R.; Marchetto, S.; Borg, J.P.; Mei, L.; Hashemolhosseini, S. LAP proteins are localized at the post-synaptic membrane of neuromuscular junctions and appear to modulate synaptic morphology and transmission. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangwala, R.; Banine, F.; Borg, J.P.; Sherman, L.S. Erbin regulates mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation and MAP kinase-dependent interactions between Merlin and adherens junction protein complexes in Schwann cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 11790–11797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, F.; Chang, C.; Lin, X.; Dai, P.; Mei, L.; Feng, X.H. Erbin inhibits transforming growth factor beta signaling through a novel Smad-interacting domain. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 6183–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, H.B.; Perez-Mancera, P.A.; Dow, L.E.; Ryan, A.; Tennstedt, P.; Bogani, D.; Elsum, I.; Greenfield, A.; Tuveson, D.A.; Simon, R.; et al. SCRIB expression is deregulated in human prostate cancer, and its deficiency in mice promotes prostate neoplasia. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4257–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, M.; Bellmunt, E.; Schwander, M.; Farinas, I.; Brenner, H.R.; Muller, U. Erbb2 regulates neuromuscular synapse formation and is essential for muscle spindle development. Development 2003, 130, 2291–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.M.; Jerchow, B.; Sheu, T.J.; Liu, B.; Costantini, F.; Puzas, J.E.; Birchmeier, W.; Hsu, W. The role of Axin2 in calvarial morphogenesis and craniosynostosis. Development 2005, 132, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessler, L.; Huraskin, D.; Jian, Y.; Eiber, N.; Hu, Z.; Proszynski, T.J.; Hashemolhosseini, S. The YAP1/TAZ-TEAD transcriptional network regulates gene expression at neuromuscular junctions in skeletal muscle fibers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 600–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, C.; Changotra, H.; Wergedal, J.E.; Kumar, A. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathways in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle in response to mechanical stretch. J. Cell Physiol. 2006, 208, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiber, N.; Rehman, M.; Kravic, B.; Rudolf, R.; Sandri, M.; Hashemolhosseini, S. Loss of Protein Kinase Csnk2b/CK2beta at Neuromuscular Junctions Affects Morphology and Dynamics of Aggregated Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors, Neuromuscular Transmission, and Synaptic Gene Expression. Cells 2019, 8, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landini, G.; Martinelli, G.; Piccinini, F. Colour deconvolution: Stain unmixing in histological imaging. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1485–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruifrok, A.C.; Johnston, D.A. Quantification of histochemical staining by color deconvolution. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 2001, 23, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Liley, A.W. An investigation of spontaneous activity at the neuromuscular junction of the rat. J. Physiol. 1956, 132, 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrock, A.W., Jr.; Dryer, S.E.; Rosen, K.M.; Gozani, S.N.; Kramer, R.; Theill, L.E.; Fischbach, G.D. Maintenance of acetylcholine receptor number by neuregulins at the neuromuscular junction in vivo. Science 1997, 276, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomp, J.J.; van Kempen, G.T.; Molenaar, P.C. Adaptation of quantal content to decreased postsynaptic sensitivity at single endplates in alpha-bungarotoxin-treated rats. J. Physiol. 1992, 458, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozhin, A.A.; Pang, K.K.; Bukharaeva, E.; Young, C.; Slater, C.R. Recovery of mouse neuromuscular junctions from single and repeated injections of botulinum neurotoxin A. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 3163–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J.N.; Henderson, D.J.; Doudney, K.; Gaston-Massuet, C.; Phillips, H.M.; Paternotte, C.; Arkell, R.; Stanier, P.; Copp, A.J. Disruption of scribble (Scrb1) causes severe neural tube defects in the circletail mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.J.; Slater, C.R. The contribution of postsynaptic folds to the safety factor for neuromuscular transmission in rat fast- and slow-twitch muscles. J. Physiol. 1997, 500 Pt. 1, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonello, T.T.; Peifer, M. Scribble: A master scaffold in polarity, adhesion, synaptogenesis, and proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 218, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolf, R.; Bogomolovas, J.; Strack, S.; Choi, K.R.; Khan, M.M.; Wagner, A.; Brohm, K.; Hanashima, A.; Gasch, A.; Labeit, D.; et al. Regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor turnover by MuRF1 connects muscle activity to endo/lysosomal and atrophy pathways. Age 2013, 35, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.M.; Strack, S.; Wild, F.; Hanashima, A.; Gasch, A.; Brohm, K.; Reischl, M.; Carnio, S.; Labeit, D.; Sandri, M.; et al. Role of autophagy, SQSTM1, SH3GLB1, and TRIM63 in the turnover of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Autophagy 2014, 10, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiskandl, S.; Woller, B.; Schlauf, M.; Schmid, J.A.; Herbst, R. Endosomal trafficking of the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK proceeds via clathrin-dependent pathways, Arf6 and actin. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 3281–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, F.; Khan, M.M.; Rudolf, R. Evidence for the subsynaptic zone as a preferential site for CHRN recycling at neuromuscular junctions. Small GTPases 2017, 10, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gessler, L.; Jian, Y.; Ngo, N.A.; Hashemolhosseini, S. The Cell Polarity Protein Scribble Is Involved in Maintaining the Structure of Neuromuscular Junctions, the Expression of Myosin Heavy Chain Genes, and Endocytic Recycling in Adult Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Cells 2025, 14, 2005. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242005

Gessler L, Jian Y, Ngo NA, Hashemolhosseini S. The Cell Polarity Protein Scribble Is Involved in Maintaining the Structure of Neuromuscular Junctions, the Expression of Myosin Heavy Chain Genes, and Endocytic Recycling in Adult Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Cells. 2025; 14(24):2005. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242005

Chicago/Turabian StyleGessler, Lea, Yongzhi Jian, Nam Anh Ngo, and Said Hashemolhosseini. 2025. "The Cell Polarity Protein Scribble Is Involved in Maintaining the Structure of Neuromuscular Junctions, the Expression of Myosin Heavy Chain Genes, and Endocytic Recycling in Adult Skeletal Muscle Fibers" Cells 14, no. 24: 2005. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242005

APA StyleGessler, L., Jian, Y., Ngo, N. A., & Hashemolhosseini, S. (2025). The Cell Polarity Protein Scribble Is Involved in Maintaining the Structure of Neuromuscular Junctions, the Expression of Myosin Heavy Chain Genes, and Endocytic Recycling in Adult Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Cells, 14(24), 2005. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242005