B Cells Can Trigger the T-Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Response Against Melanocytes in Psoriasis

Highlights

- We find that under inflammatory conditions, B cells from streptococci-infected tonsils and blood of HLA-C*06:02-positive psoriasis patients activate a melanocyte-reactive T-cell receptor from a pathogenic psoriatic CD8+ T cell clone and also have autostimulatory properties for CD8+ T cells.

- We identify several self-peptides from the complex HLA-C*06:02 immunopeptidomes of B cells that may serve as autoantigens to activate the lesional psoriatic autoimmune response against melanocytes due to T-cell receptor polyspecificity.

- The proinflammatory environment of streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis, as an important trigger for psoriasis, might break the tolerance of pathogenic psoriatic CD8+ T cells to autoantigens presented by HLA-C*06:02 on B cells that subsequently react against melanocytes, inducing psoriasis.

- The findings open up potential avenues for the development of therapies targeting the pathogenic B-T cell interaction in psoriasis.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statements

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Human Materials

2.4. Cell Lines

2.5. Cell Separation and Cell Sorting

2.6. Vα3S1/Vβ13S1-TCR Hybridoma Activation Assays

2.7. Autologous Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction

2.8. Analysis of HLA-C Expression

2.9. Isolation of HLA Class I Ligands for Immunopeptidomics

2.10. Analysis of HLA Class I Ligands by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)

2.11. Definition of the Peptide Recognition Motif of the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR

2.12. Screening HLA-C*06:02-Immunopeptidomes with the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR Peptide Recognition Motif

2.13. Cloning and Transfection of Candidate Peptides, Peptide Presentation

2.14. Transcriptome Analysis of Cell Lines

2.15. Statistics and Reproducibility

3. Results

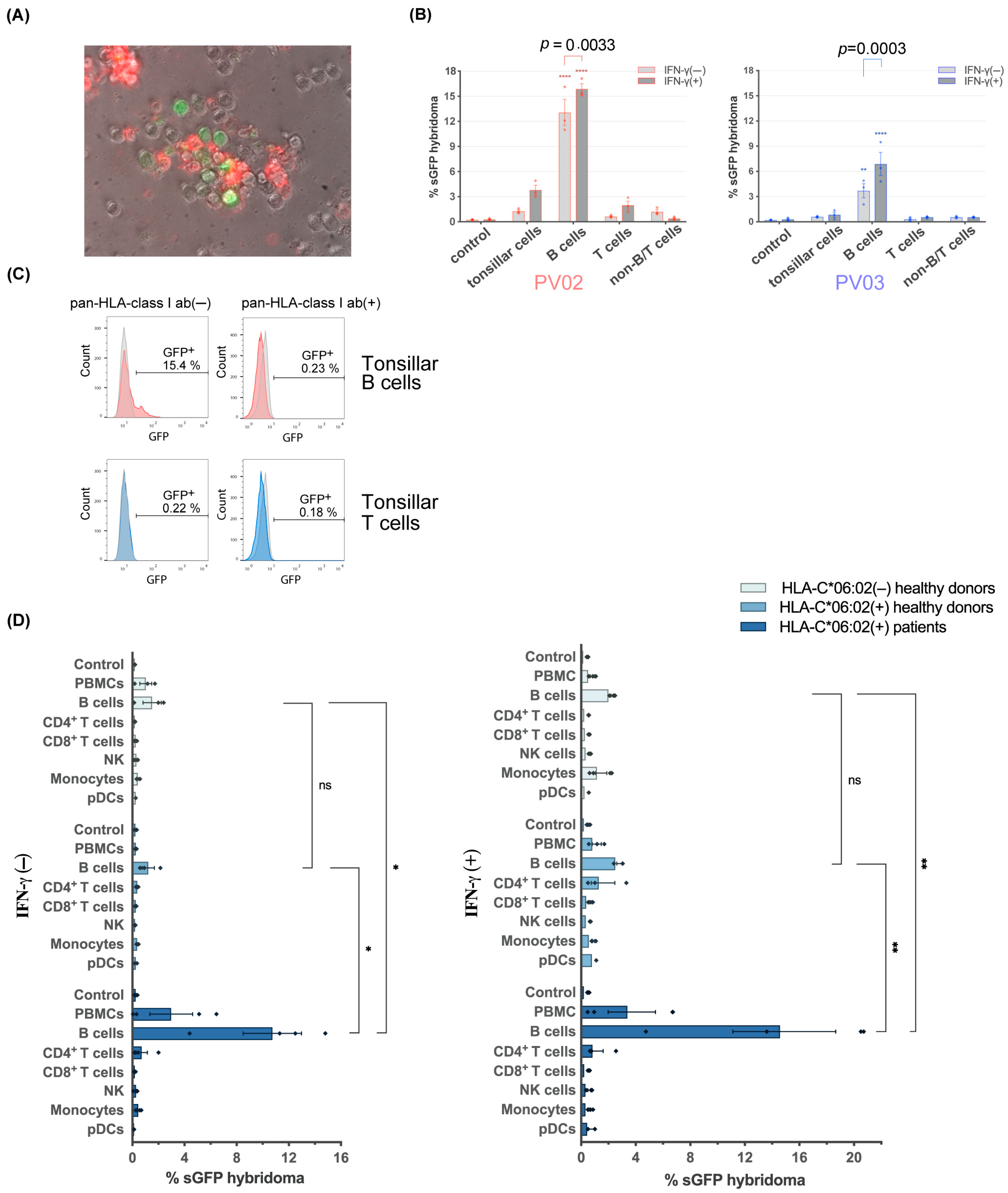

3.1. B Cells from Tonsils of HLA-C*06:02+ Patients with Streptococci-Driven Psoriasis Stimulate the Melanocyte-Specific Psoriatic Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR

3.2. Blood B Cells of HLA-C*06:02+ Psoriasis Patients Activate the Psoriatic Vα3S1/Vβ13S1-TCR Hybridoma

3.3. Stimulation of the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1-TCR Hybridoma by B Cells Is HLA-C*06:02-Restricted

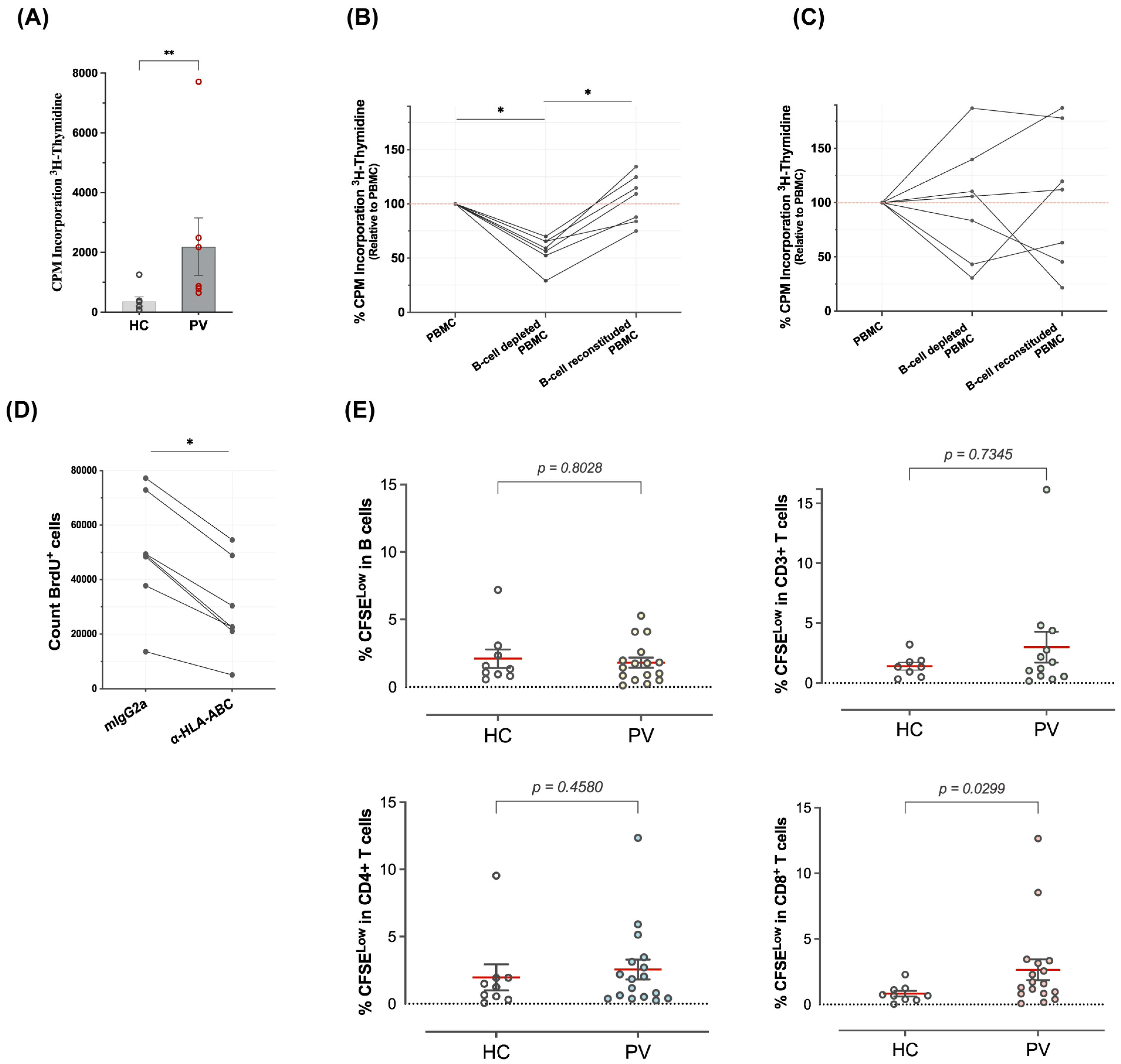

3.4. B Cells Are Autostimulatory for CD8+ T Cells from Psoriasis Patients

3.5. The HLA Class I-Deficient HLA-C*06:02-Transfected B-Cell Lines C1R and 721.221 Do Not Stimulate the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR

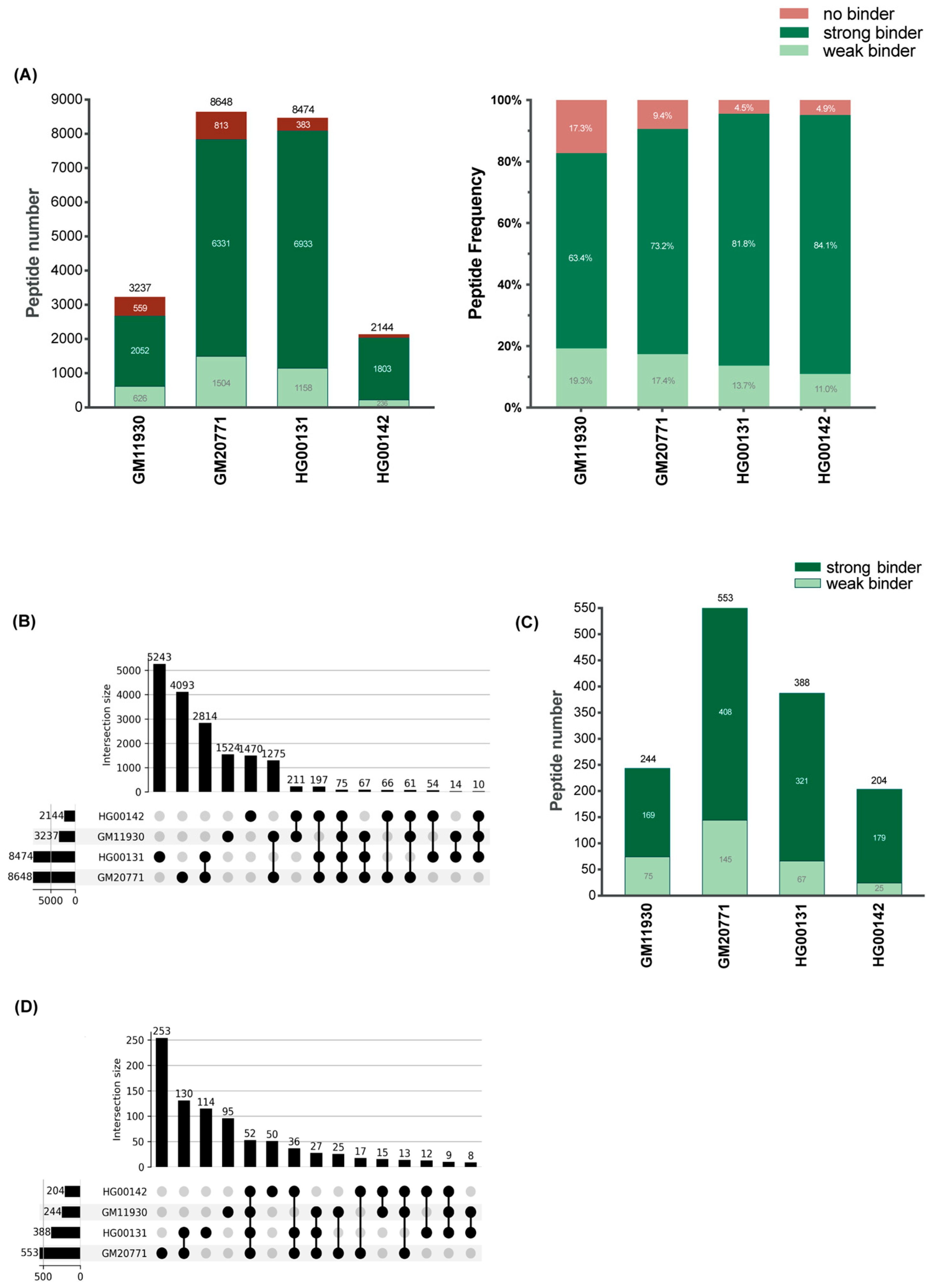

3.6. The HLA-C*06:02 Immunopeptidomes of Four HLA-C*06:02-Homzygous B-Cell Lines Are Complex

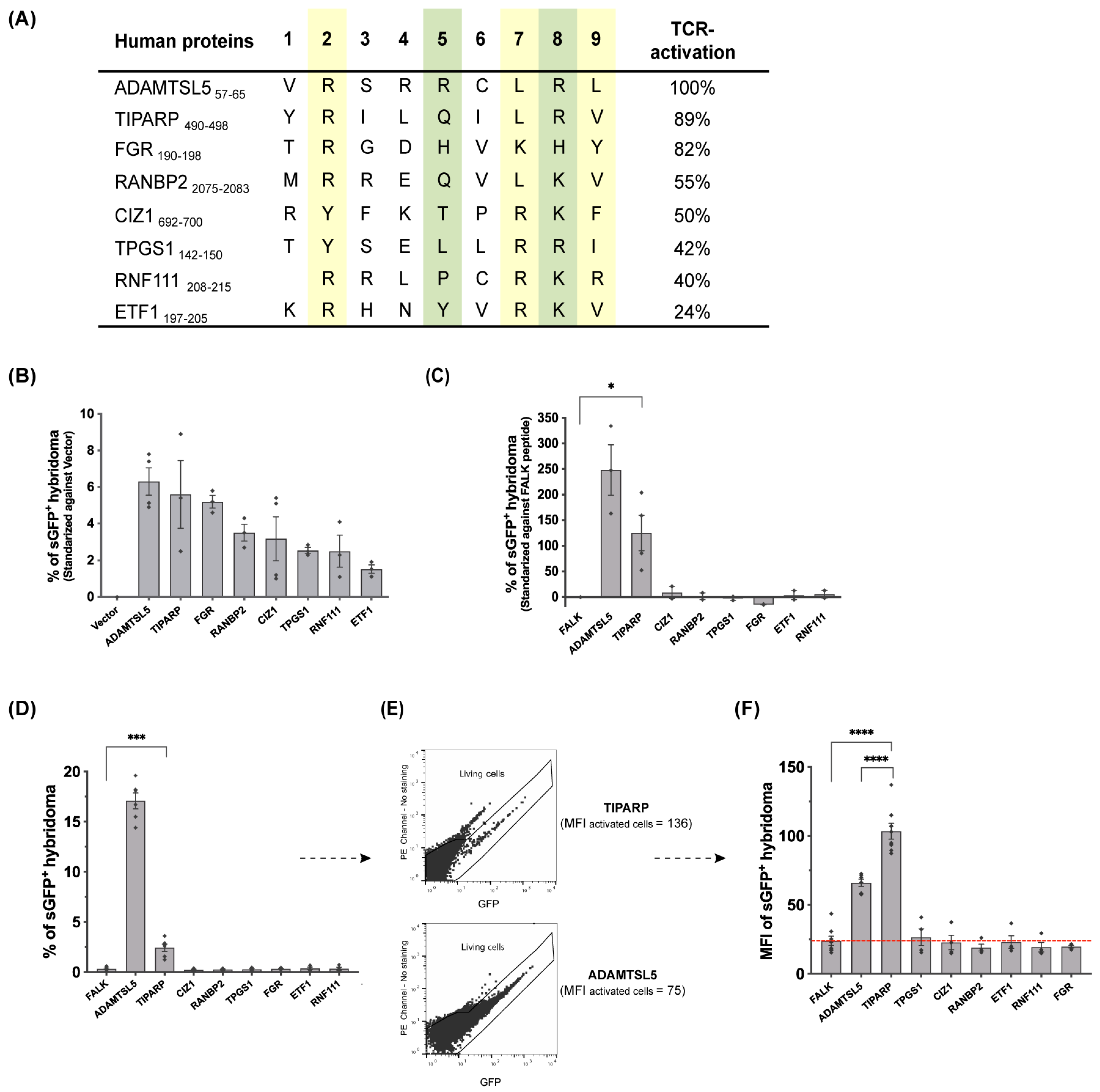

3.7. Various Self-Peptides from the HLA-C*06:02 Immunopeptidomes of HLA-C*06:02-Homozygous B-Cell Lines Are Autoantigens of the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR

3.8. The Antigenicity of the Parental Proteins of the Peptides Stimulating the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR Is Cell-Type Dependent

3.9. The TiPARP Peptide Stimulated the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR Both as a Plasmid-Encoded and Exogenously Applied Synthetic Peptide

3.10. Binding Prediction Reveals That Other HLA Class I Alleles Associated with Psoriasis May Also Present the Vα3S1/Vβ13S1 TCR Ligands

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBV | Epstein–Barr Virus |

| BCL | B-cell line |

| AMLR | autologous mixed lymphocyte reaction |

| AP | autoproliferation |

| PV | psoriasis patient |

| HC | healthy control |

| ERAP1 | endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 |

| sGFP | superfolder green fluorescent protein |

| MFI | mean fluorescence intensity |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

References

- Dand, N.; Stuart, P.E.; Bowes, J.; Ellinghaus, D.; Nititham, J.; Saklatvala, J.R.; Teder-Laving, M.; Thomas, L.F.; Traks, T.; Uebe, S.; et al. GWAS meta-analysis of psoriasis identifies new susceptibility alleles impacting disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Stuart, P.E.; Tian, C.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Das, S.; Zawistowski, M.; Ellinghaus, E.; Barker, J.N.; Chandran, V.; Dand, N.; et al. Large scale meta-analysis characterizes genetic architecture for common psoriasis associated variants. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.P.; Stuart, P.E.; Nistor, I.; Hiremagalore, R.; Chia, N.V.; Jenisch, S.; Weichenthal, M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Lim, H.W.; Christophers, E.; et al. Sequence and Haplotype Analysis Supports HLA-C as the Psoriasis Susceptibility 1 Gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 78, 827–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Cao, H.; Zuo, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, R.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; et al. Deep sequencing of the MHC region in the Chinese population contributes to studies of complex disease. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meglio, P.; Villanova, F.; Navarini, A.A.; Mylonas, A.; Tosi, I.; Nestle, F.O.; Conrad, C. Targeting CD8+ T cells prevents psoriasis development. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 274–276.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.C.; Smith, L.R.; Froning, K.J.; Schwabe, B.J.; Laxer, J.A.; Caralli, L.L.; Kurland, H.H.; Karasek, M.A.; Wilkinson, D.I.; Carlo, D.J. CD8+ T cells in psoriatic lesions preferentially use T-cell receptor V beta 3 and/or V beta 13.1 genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 9282–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Bhonsle, L.; Besgen, P.; Nickel, J.; Backes, A.; Held, K.; Vollmer, S.; Dornmair, K.; Prinz, J.C. Analysis of the Paired Tcr Alpha- and Beta-Chains of Single Human T Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37338. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Chang, H.-W.; Huang, Z.-M.; Nakamura, M.; Sekhon, S.; Ahn, R.; Munoz-Sandoval, P.; Bhattarai, S.; Beck, K.M.; Sanchez, I.M.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of psoriatic skin identifies pathogenic Tc17 cell subsets and reveals distinctions between CD8+ T cells in autoimmunity and cancer. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 147, 2370–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Plazyo, O.; Billi, A.C.; Tsoi, L.C.; Xing, X.; Wasikowski, R.; Gharaee-Kermani, M.; Hile, G.; Jiang, Y.; Harms, P.W.; et al. Single cell and spatial sequencing define processes by which keratinocytes and fibroblasts amplify inflammatory responses in psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C.; Fernández, A.S.; Carrillo, J.M.; Romero, P.; Molina, I.J.; Moreno, J.C.; Santamaría, M. IL-17-producing CD8+ T lymphocytes from psoriasis skin plaques are cytotoxic effector cells that secrete Th17-related cytokines. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 86, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, S.; Kerl, K.; Ertop Doğan, P.; Vollmer, S.; Puchta, U.; He, M.; Arakawa, Y.; Heper, A.O.; Karal-Öktem, A.; Hartmann, D.; et al. Lesional Activation of T(C) 17 Cells in Behcet Disease and Psoriasis Supports Hla Class I-Mediated Autoimmune Responses. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, S.; Schlums, H.; Sérézal, I.G.; Martini, E.; Chiang, S.C.; Marquardt, N.; Gibbs, A.; Detlofsson, E.; Introini, A.; Forkel, M.; et al. CD49a Expression Defines Tissue-Resident CD8+ T Cells Poised for Cytotoxic Function in Human Skin. Immunity 2017, 46, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakawa, A.; Siewert, K.; Stöhr, J.; Besgen, P.; Kim, S.-M.; Rühl, G.; Nickel, J.; Vollmer, S.; Thomas, P.; Krebs, S.; et al. Melanocyte antigen triggers autoimmunity in human psoriasis. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, A.; Reeves, E.; Vollmer, S.; Arakawa, Y.; He, M.; Galinski, A.; Stöhr, J.; Dornmair, K.; James, E.; Prinz, J.C. ERAP1 Controls the Autoimmune Response against Melanocytes in Psoriasis by Generating the Melanocyte Autoantigen and Regulating Its Amount for HLA-C*06:02 Presentation. J. Immunol. 2021, 207, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Littler, D.R.; Mobbs, J.I.; Braun, A.; Baker, D.G.; Tennant, L.; Purcell, A.W.; Vivian, J.P.; Rossjohn, J. Complimentary electrostatics dominate T-cell receptor binding to a psoriasis-associated peptide antigen presented by human leukocyte antigen C*06:02. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, T.; Christophers, E. Psoriasis of early and late onset: Characterization of two types of psoriasis vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1985, 13, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorleifsdottir, R.H.; Sigurdardottir, S.L.; Sigurgeirsson, B.; Olafsson, J.H.; Petersen, H.; Sigurdsson, M.I.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Johnston, A.; Valdimarsson, H. HLA-Cw6 homozygosity in plaque psoriasis is associated with streptococcal throat infections and pronounced improvement after tonsillectomy: A prospective case series. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudjonsson, J.; Thorarinsson, A.; Sigurgeirsson, B.; Kristinsson, K.; Valdimarsson, H. Streptococcal throat infections and exacerbation of chronic plaque psoriasis: A prospective study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 149, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisenseel, P.; Laumbacher, B.; Besgen, P.; Ludolph-Hauser, D.; Herzinger, T.; Roecken, M.; Wank, R.; Prinz, J.C. Streptococcal infection distinguishes different types of psoriasis: Table 1. J. Med Genet. 2002, 39, 767–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.; Travers, J.B.; Giorno, R.; Norris, D.A.; Skinner, R.; Aelion, J.; Kazemi, L.V.; Kim, M.H.; Trumble, A.E.; Kotb, M. Evidence for a streptococcal superantigen-driven process in acute guttate psoriasis. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 2106–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdimarsson, H.; Thorleifsdottir, R.H.; Sigurdardottir, S.L.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Johnston, A. Psoriasis—As an autoimmune disease caused by molecular mimicry. Trends Immunol. 2009, 30, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besgen, P.; Trommler, P.; Vollmer, S.; Prinz, J.C. Ezrin, Maspin, Peroxiredoxin 2, and Heat Shock Protein 27: Potential Targets of a Streptococcal-Induced Autoimmune Response in Psoriasis. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 5392–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diluvio, L.; Vollmer, S.; Besgen, P.; Ellwart, J.W.; Chimenti, S.; Prinz, J.C. Identical TCR β-Chain Rearrangements in Streptococcal Angina and Skin Lesions of Patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 7104–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, T.; Horii, M.; Kudo, K.; Nishio, J.; Fujii, K.; Fushida, N.; Mizumaki, K.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Matsushita, T. Disrupted B-Cell Cytokine Homeostasis in Psoriasis: The Impact of Elevated IL-6 and Impaired IL-10 Production. J. Dermatol. 2025, 52, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Yanaba, K.; Umezawa, Y.; Yoshihara, Y.; Kikuchi, S.; Ishiuji, Y.; Saeki, H.; Nakagawa, H. IL-10-producing regulatory B cells are decreased in patients with psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2016, 81, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavropoulos, A.; Varna, A.; Zafiriou, E.; Liaskos, C.; Alexiou, I.; Roussaki-Schulze, A.; Vlychou, M.; Katsiari, C.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Sakkas, L.I. IL-10 producing Bregs are impaired in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis and inversely correlate with IL-17- and IFNγ-producing T cells. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 184, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussi, A.; Merleev, A.; Barton, V.; Le, S.; Marusina, A.; Luxardi, G.; Kirma, J.; Xing, X.; Adamopoulos, I.; Fung, M.; et al. Transcriptome mining and B cell depletion support a role for B cells in psoriasis pathophysiology. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2019, 96, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ding, Y.; Yi, X.; Zheng, J. CD19+ B cell subsets in the peripheral blood and skin lesions of psoriasis patients and their correlations with disease severity. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, e5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombrello, M.J.; Kastner, D.L.; Remmers, E.F. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated amino-peptidase 1 and rheumatic disease. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2015, 27, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, K.; Rötzschke, O.; Stevanovié, S.; Jung, G.; Rammensee, H.-G. Allele-specific motifs revealed by sequencing of self-peptides eluted from MHC molecules. Nature 1991, 351, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.E.; Zhou, Z.; Landry, L.G.; Anderson, A.M.; Alkanani, A.K.; Fischer, J.; Peakman, M.; Mallone, R.; Campbell, K.; Michels, A.W.; et al. Multiplex T Cell Stimulation Assay Utilizing a T Cell Activation Reporter-Based Detection System. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, S.; Schneider, C.K.; Malotka, J.; Nong, X.; Engel, A.G.; Wekerle, H.; Hohlfeld, R.; Dornmair, K. Reconstitution of paired T cell receptor α- and β-chains from microdissected single cells of human inflammatory tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12057–12062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewert, K.; Malotka, J.; Kawakami, N.; Wekerle, H.; Hohlfeld, R.; Dornmair, K. Unbiased identification of target antigens of CD8+ T cells with combinatorial libraries coding for short peptides. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, M.; Cruz-Garcia, Y.; Rech, A.; Meierjohann, S.; Erhard, F.; Schilling, B.; Schlosser, A. Extending the Mass Spectrometry-Detectable Landscape of MHC Peptides by Use of Restricted Access Material. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 14214–14222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurtz, V.; Paul, S.; Andreatta, M.; Marcatili, P.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.0: Improved Peptide–MHC Class I Interaction Predictions Integrating Eluted Ligand and Peptide Binding Affinity Data. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 3360–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.; Harndahl, M.; Stryhn, A.; Boucherma, R.; Nielsen, L.L.; Lemonnier, F.A.; Nielsen, M.; Buus, S. Uncovering the Peptide-Binding Specificities of HLA-C: A General Strategy To Determine the Specificity of Any MHC Class I Molecule. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 4790–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobbs, J.I.; Illing, P.T.; Dudek, N.L.; Brooks, A.G.; Baker, D.G.; Purcell, A.W.; Rossjohn, J.; Vivian, J.P. The molecular basis for peptide repertoire selection in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) C*06:02 molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 17203–17215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, M.; Schuster, H.; Backert, L.; Ghosh, M.; Rammensee, H.-G.; Stevanović, S. Unveiling the Peptide Motifs of HLA-C and HLA-G from Naturally Presented Peptides and Generation of Binding Prediction Matrices. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 2639–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimoto, T.; Arakawa, Y.; Vural, S.; Stöhr, J.; Vollmer, S.; Galinski, A.; Siewert, K.; Rühl, G.; Poluektov, Y.; Delcommenne, M.; et al. Multiple environmental antigens may trigger autoimmunity in psoriasis through T-cell receptor polyspecificity. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1374581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; DeMars, R. Production of human cells expressing individual transferred HLA-A,-B,-C genes using an HLA-A,-B,-C null human cell line. J. Immunol. 1989, 142, 3320–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemmour, J.; Little, A.M.; Schendel, D.J.; Parham, P. The HLA-A,B “negative” mutant cell line C1R expresses a novel HLA-B35 allele, which also has a point mutation in the translation initiation codon. J. Immunol. 1992, 148, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storkus, W.J.; Howell, D.N.; Salter, R.D.; Dawson, J.R.; Cresswell, P. NK susceptibility varies inversely with target cell class I HLA antigen expression. J. Immunol. 1987, 138, 1657–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, K.; Rötzschke, O.; Grahovac, B.; Schendel, D.; Stevanović, S.; Gnau, V.; Jung, G.; Strominger, J.L.; Rammensee, H.G. Allele-specific peptide ligand motifs of HLA-C molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 12005–12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, B.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: Improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacker, M.; Bauer, J.; Wessling, L.; Dubbelaar, M.; Nelde, A.; Rammensee, H.-G.; Walz, J.S. Immunoprecipitation methods impact the peptide repertoire in immunopeptidomics. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1219720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloverpris, H.; Fomsgaard, A.; Handley, A.; Ackland, J.; Sullivan, M.; Goulder, P. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) exposure to human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) abolish T cell responses only in high concentrations and following coincubation for more than two hours. J. Immunol. Methods 2010, 356, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neefjes, J.; Jongsma, M.L.M.; Paul, P.; Bakke, O. Towards a systems understanding of MHC class I and MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroon, M.; Winchester, R.; Giles, J.T.; Heffernan, E.; FitzGerald, O. Certain class I HLA alleles and haplotypes implicated in susceptibility play a role in determining specific features of the psoriatic arthritis phenotype. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; He, F.; Zhao, X.; Hou, R.; Lin, H.; Shen, J.; Wu, X.; Liao, Q.; Xing, J.; et al. Cross-sectional study reveals that HLA-C*07:02 is a potential biomarker of early onset/lesion severity of psoriasis. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Huang, H.; Hu, Z.; Yuan, T.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, X. Two Variants in the NOTCH4 and HLA-C Genes Contribute to Familial Clustering of Psoriasis. Int. J. Genom. 2020, 2020, 6907378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi, T.; Ota, T.; Manabe, Y.; Ikoma, N.; Ozawa, A.; Terui, T.; Ikeda, S.; Inoko, H.; Oka, A. HLA-C*12:02 is a susceptibility factor in late-onset type of psoriasis in Japanese. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 84, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, V.; Bull, S.B.; Pellett, F.J.; Ayearst, R.; Rahman, P.; Gladman, D.D. Human leukocyte antigen alleles and susceptibility to psoriatic arthritis. Hum. Immunol. 2013, 74, 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, J.C. Human Leukocyte Antigen-Class I Alleles and the Autoreactive T Cell Response in Psoriasis Pathogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, O.; Haroon, M.; Giles, J.T.; Winchester, R. Concepts of pathogenesis in psoriatic arthritis: Genotype determines clinical phenotype. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsun, N.; Pirmit, S.; Ozkaya, D.; Çelik, Ş.; Rezvani, A.; Cengiz, F.P.; Kekik, C. The HLA-Cw12 Allele Is an Important Susceptibility Allele for Psoriasis and Is Associated with Resistant Psoriasis in the Turkish Population. Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 7848314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, A.; Riedel, M.; Cornette, J.; Udell, J.; Vasmatzis, G. Hydrophobicity identifies false positives and false negatives in peptide-MHC binding. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1034810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Li, F.; Leier, A.; Marquez-Lago, T.T.; Giam, K.; Croft, N.P.; Akutsu, T.; Smith, A.I.; Li, J.; Rossjohn, J.; et al. A comprehensive review and performance evaluation of bioinformatics tools for HLA class I peptide-binding prediction. Briefings Bioinform. 2020, 21, 1119–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle, F.O.; Turka, L.A.; Nickoloff, B.J. Characterization of dermal dendritic cells in psoriasis. Autostimulation of T lymphocytes and induction of Th1 type cytokines. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, J.C. Immunogenic self-peptides—The great unknowns in autoimmunity: Identifying T-cell epitopes driving the autoimmune response in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1097871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewell, A.K. Why must T cells be cross-reactive? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnbaum, M.E.; Mendoza, J.L.; Sethi, D.K.; Dong, S.; Glanville, J.; Dobbins, J.; Özkan, E.; Davis, M.M.; Wucherpfennig, K.W.; Garcia, K.C. Deconstructing the Peptide-MHC Specificity of T Cell Recognition. Cell 2014, 157, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, L.N.; Jiang, W.; Bhamidipati, K.; Millican, M.; Macaubas, C.; Hung, S.-C.; Mellins, E.D. The Other Function: Class II-Restricted Antigen Presentation by B Cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohme, M.; Hotz, C.; Stevanović, S.; Binder, T.; Lee, J.H.; Okoniewski, M.; Eiermann, T.; Sospedra, M.; Rammensee, H.G.; Martin, R. Hla-Dr15-Derived Self-Peptides Are Involved in Increased Autologous T Cell Proliferation in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain 2013, 136 Pt 6, 1783–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelcic, I.; Al Nimer, F.; Wang, J.; Lentsch, V.; Planas, R.; Jelcic, I.; Madjovski, A.; Ruhrmann, S.; Faigle, W.; Frauenknecht, K.; et al. Memory B Cells Activate Brain-Homing, Autoreactive CD4+ T Cells in Multiple Sclerosis. Cell 2018, 175, 85–100.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Larsen, M.S.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature 2020, 577, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlgren, M.; Dubois, P.M.; Tomkowiak, M.; Sjögren, T.; Marvel, J. Resting Memory CD8+ T Cells are Hyperreactive to Antigenic Challenge In Vitro. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 184, 2141–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enouz, S.; Carrié, L.; Merkler, D.; Bevan, M.J.; Zehn, D. Autoreactive T cells bypass negative selection and respond to self-antigen stimulation during infection. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezys, V.; LefrançoIs, L. Cutting Edge: Inflammatory Signals Drive Organ-Specific Autoimmunity to Normally Cross-Tolerizing Endogenous Antigen. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 6677–6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Yao, Z. Roles of Infection in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-C.; Huang, I.-H.; Wang, C.-W.; Tsai, C.-C.; Chung, W.-H.; Chen, C.-B. New Onset and Exacerbations of Psoriasis Following COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 775–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, A.T.; Fetil, E.; Akarsu, S.; Ozbagcivan, O.; Babayeva, L. Possible Triggering Effect of Influenza Vaccination on Psoriasis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 258430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Deng, Q.; Deng, L.; Xun, T.; Huang, T.; Zhao, J.; Wei, S.; Zhao, C.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Alterations of gut microbiota for the onset and treatment of psoriasis: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 998, 177521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhaș, M.C.; Candrea, R.; Gavrilaș, L.I.; Miere, D.; Tătaru, A.; Boca, A.; Cătinean, A. Transforming Psoriasis Care: Probiotics and Prebiotics as Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaclavkova, A.; Chimenti, S.; Arenberger, P.; Holló, P.; Sator, P.-G.; Burcklen, M.; Stefani, M.; D’Ambrosio, D. Oral ponesimod in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’aMbrosio, D.; Freedman, M.S.; Prinz, J. Ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator: A potential treatment for multiple sclerosis and other immune-mediated diseases. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2016, 7, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehncke, W.H. Efalizumab in the Treatment of Psoriasis. Biologics 2007, 1, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Bonifacio, K.M.; Hawkes, J.E.; Kunjravia, N.; Cueto, I.; Li, X.; Gonzalez, J.; Garcet, S.; Krueger, J.G. Autoantigens ADAMTSL5 and LL37 are significantly upregulated in active Psoriasis and localized with keratinocytes, dendritic cells and other leukocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, J.C. Antigen Processing, Presentation, and Tolerance: Role in Autoimmune Skin Diseases. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 142, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, H.; Shao, W.; Weiss, T.; Pedrioli, P.G.; Roth, P.; Weller, M.; Campbell, D.S.; Deutsch, E.W.; Moritz, R.L.; Planz, O.; et al. A tissue-based draft map of the murine MHC class I immunopeptidome. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, J.A.; Lesenfants, J.; Vigneron, N.; Eynde, B.J.V.D. Functional Differences between Proteasome Subtypes. Cells 2022, 11, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, B.; Ruppert, T.; Kuehn, L.; Merforth, S.; Kloetzel, P.-M. Different proteasome subtypes in a single tissue exhibit different enzymatic properties 1 1Edited by R. Huber. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 303, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloetzel, P.M. Antigen Processing by the Proteasome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 2, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, A.; Bichmann, L.; Kuchenbecker, L.; Kowalewski, D.J.; Freudenmann, L.K.; Backert, L.; Mühlenbruch, L.; Szolek, A.; Lübke, M.; Wagner, P.; et al. HLA Ligand Atlas: A benign reference of HLA-presented peptides to improve T-cell-based cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisan, T.; Levitsky, V.; Masucci, M.G. Variations in proteasome subunit composition and enzymatic activity in B-lymphoma lines and normal B cells. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 88, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inholz, K.; Anderl, J.L.; Klawitter, M.; Goebel, H.; Maurits, E.; Kirk, C.J.; Fan, R.A.; Basler, M. Proteasome composition in immune cells implies special immune-cell-specific immunoproteasome function. Eur. J. Immunol. 2024, 54, e2350613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.; Berger, T.; Groettrup, M.; Basler, M. Immunoproteasome Inhibition Impairs T and B Cell Activation by Restraining ERK Signaling and Proteostasis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalet, A.; Stroobant, V.; Vigneron, N.; Eynde, B.J.V.D. Differences in the production of spliced antigenic peptides by the standard proteasome and the immunoproteasome. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigneron, N.; Eynde, B.J.V.D. Proteasome Subtypes and Regulators in the Processing of Antigenic Peptides Presented by Class I Molecules of the Major Histocompatibility Complex. Biomolecules 2014, 4, 994–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, M.; Mundt, S.; Bitzer, A.; Schmidt, C.; Groettrup, M. The immunoproteasome: A novel drug target for autoimmune diseases. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2015, 33, S74–S79. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaora, S.; Lee, J.S.; Barnea, E.; Levy, R.; Greenberg, P.; Alon, M.; Yagel, G.; Bar Eli, G.; Oren, R.; Peri, A.; et al. Immunoproteasome expression is associated with better prognosis and response to checkpoint therapies in melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, K.; Knights, A.J.; Anaka, M.; Schittenhelm, R.B.; Purcell, A.W.; Behren, A.; Cebon, J. Mismatch in epitope specificities between IFNγ inflamed and uninflamed conditions leads to escape from T lymphocyte killing in melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2016, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Tsai, T.-F. HLA-Cw6 and psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, I.A.; Chang, S.-C.; Saric, T.; Keys, J.A.; Favreau, J.M.; Goldberg, A.L.; Rock, K.L. The ER aminopeptidase ERAP1 enhances or limits antigen presentation by trimming epitopes to 8–9 residues. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, A.; Capon, F.; Spencer, C.C.; Knight, J.; Weale, M.E.; Allen, M.H.; Barton, A.; Band, G.; Bellenguez, C.; Bergboer, J.G.; et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new psoriasis susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA-C and ERAP1. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arden, B.; Clark, S.P.; Kabelitz, D.; Mak, T.W. Human T-cell receptor variable gene segment families. Immunogenetics 1995, 42, 455–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Qiu, J.; Lin, Z.; Li, W.; Haley, C.; Mui, U.N.; Ning, J.; Tyring, S.K.; Wu, T. Identification of Novel Autoantibodies Associated With Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, M.; Carbone, M.L.; Scaglione, G.L.; Scarponi, C.; Di Francesco, V.; Pallotta, S.; De Galitiis, F.; Rahimi, S.; Madonna, S.; Failla, C.M.; et al. Identification of immunological patterns characterizing immune-related psoriasis reactions in oncological patients in therapy with anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1346687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Spain, S.L.; Knight, J.; Ellinghaus, E.; Stuart, P.E.; Capon, F.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Tejasvi, T.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.T.; Stuart, P.E.; Raja, K.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Tejasvi, T.; Yang, J.; Chandran, V.; Das, S.; Callis-Duffin, K.; Ellinghaus, E.; et al. Genetic signature to provide robust risk assessment of psoriatic arthritis development in psoriasis patients. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbrink, R.; Spoorenberg, A.; Verstappen, G.M.P.J.; Kroese, F.G.M. B Cell Involvement in the Pathogenesis of Ankylosing Spondylitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Garner, L.I.; Zvyagin, I.V.; Paley, M.A.; Komech, E.A.; Jude, K.M.; Zhao, X.; Fernandes, R.A.; Hassman, L.M.; Paley, G.L.; et al. Autoimmunity-associated T cell receptors recognize HLA-B*27-bound peptides. Nature 2022, 612, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veale, D.; Barnes, L.; Rogers, S.; FitzGerald, O. Immunohistochemical markers for arthritis in psoriasis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1994, 53, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorleifsdottir, R.H.; Sigurdardottir, S.L.; Sigurgeirsson, B.; Olafsson, J.H.; Sigurdsson, M.I.; Petersen, H.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Johnston, A.; Valdimarsson, H. Patient-reported Outcomes and Clinical Response in Patients with Moderate-to-severe Plaque Psoriasis Treated with Tonsillectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| BCL | Total Peptide Yield | HLA-C*06:02 8-mers | HLA-C*06:02 9-mers | HLA-C*06:02 10-mers | HLA-C*06:02 11-mers | ERAP1 Haplotype | Stimulatory Peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM11930 | 3237 | 15 (6.15%) | 229 (93.85%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) | Hap2/Hap2 | FGR, CIZ1 |

| HG00142 | 2144 | 5 (2.45%) | 199 (97.55%) | 0 (%) | 0 (0%) | Hap10/Hap10 | RANBP2, ETF1 |

| GM20771 | 8648 | 14 (2.53%) | 534 (96.56%) | 5 (0.90%) | 0 (0%) | Hap2/Hap10 | TiPARP, TPGS1 |

| HG00131 | 8474 | 16 (4.12%) | 370 (95.36%) | 1 (0.25%) | 1 (0.25%) | Hap1/Hap2 | FGR, RNF111 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, M.; Bernhardt, M.; Arakawa, A.; Kim, S.-M.; Vollmer, S.; Summer, B.; Arakawa, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Schlosser, A.; Prinz, J.C. B Cells Can Trigger the T-Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Response Against Melanocytes in Psoriasis. Cells 2025, 14, 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242002

He M, Bernhardt M, Arakawa A, Kim S-M, Vollmer S, Summer B, Arakawa Y, Ishimoto T, Schlosser A, Prinz JC. B Cells Can Trigger the T-Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Response Against Melanocytes in Psoriasis. Cells. 2025; 14(24):2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242002

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Mengwen, Melissa Bernhardt, Akiko Arakawa, Song-Min Kim, Sigrid Vollmer, Burkard Summer, Yukiyasu Arakawa, Tatsushi Ishimoto, Andreas Schlosser, and Jörg Christoph Prinz. 2025. "B Cells Can Trigger the T-Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Response Against Melanocytes in Psoriasis" Cells 14, no. 24: 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242002

APA StyleHe, M., Bernhardt, M., Arakawa, A., Kim, S.-M., Vollmer, S., Summer, B., Arakawa, Y., Ishimoto, T., Schlosser, A., & Prinz, J. C. (2025). B Cells Can Trigger the T-Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Response Against Melanocytes in Psoriasis. Cells, 14(24), 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242002