Graphene and Its Derivatives as Modulators of Macrophage Polarization in Cutaneous Wound Healing

Highlights

- The modulation of macrophage polarization using graphene-based materials offers a promising approach to regulating wound healing.

- The effects of graphene-based materials may occur either after their internalization by the macrophages or through direct contact in the form of a scaffold or solid surface.

- Characterization of the graphene-based materials is essential to assess their action potential (toxicity or compatibility).

- Proper management of macrophage polarization (M1 or M2) using graphene-based materials could enable the design of novel immunomodulatory materials for implantation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Graphene and Its Derivatives

2.1. Methods of Graphene Production

2.2. Methods for Graphene Characterization

3. Wound Healing with Highlights of MØ Function

4. GBMs as an Immunomodulatory Material

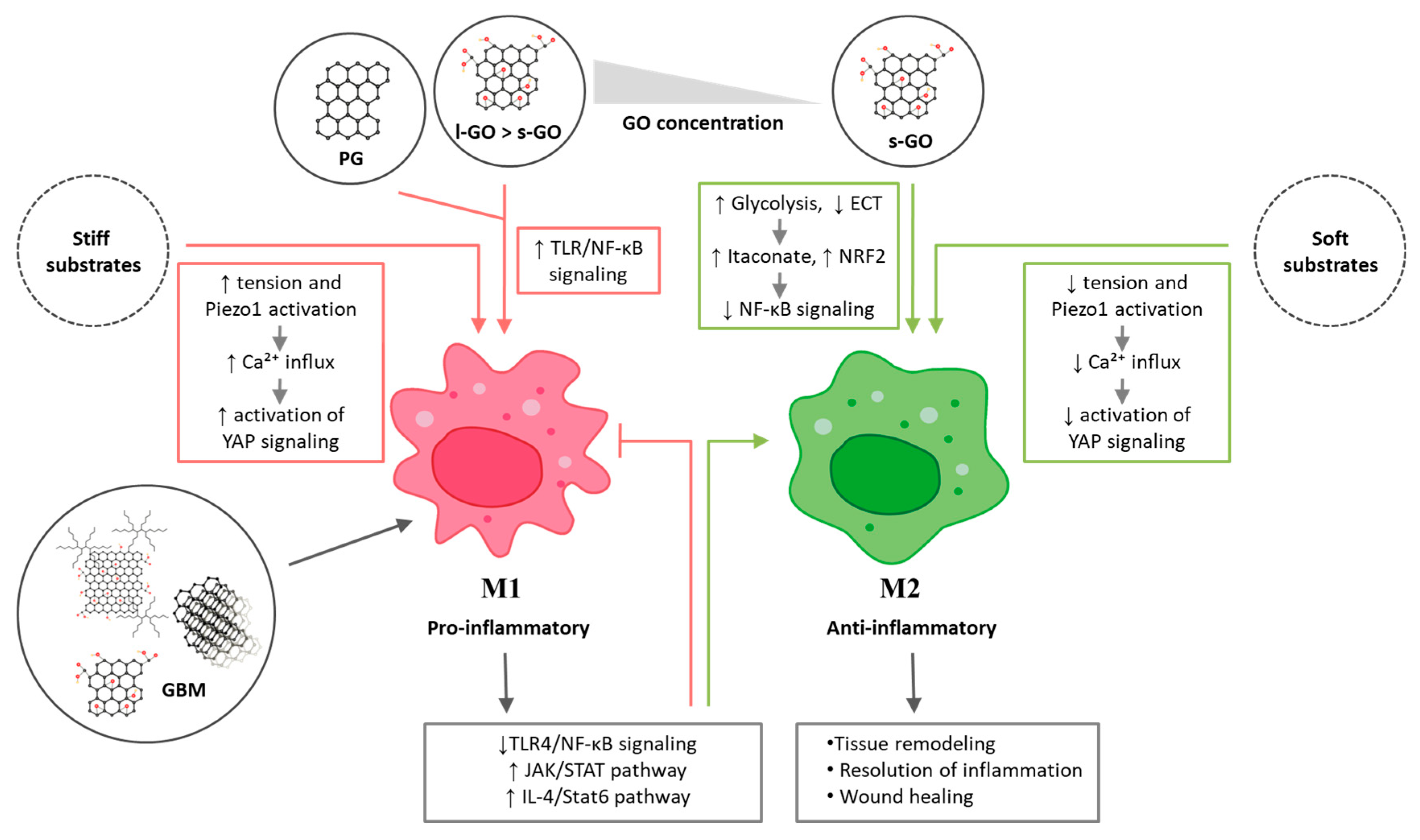

4.1. Modulation of MØ Polarization After Direct Contact with GBMs Suspension

4.1.1. GBMs Entry into MØ

4.1.2. Impact of GBM Suspension on MØ Polarization

4.2. Modulation of MØ Polarization by GBMs as a Scaffold/Ground/Substrate

4.3. Proposed Mechanisms of GBM-Induced MØ Polarization

5. Challenges in Designing MØ Polarization Studies with GBMs

| Material | Material Composition and Characterization | Action | Activity | In Vitro/In Vivo | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

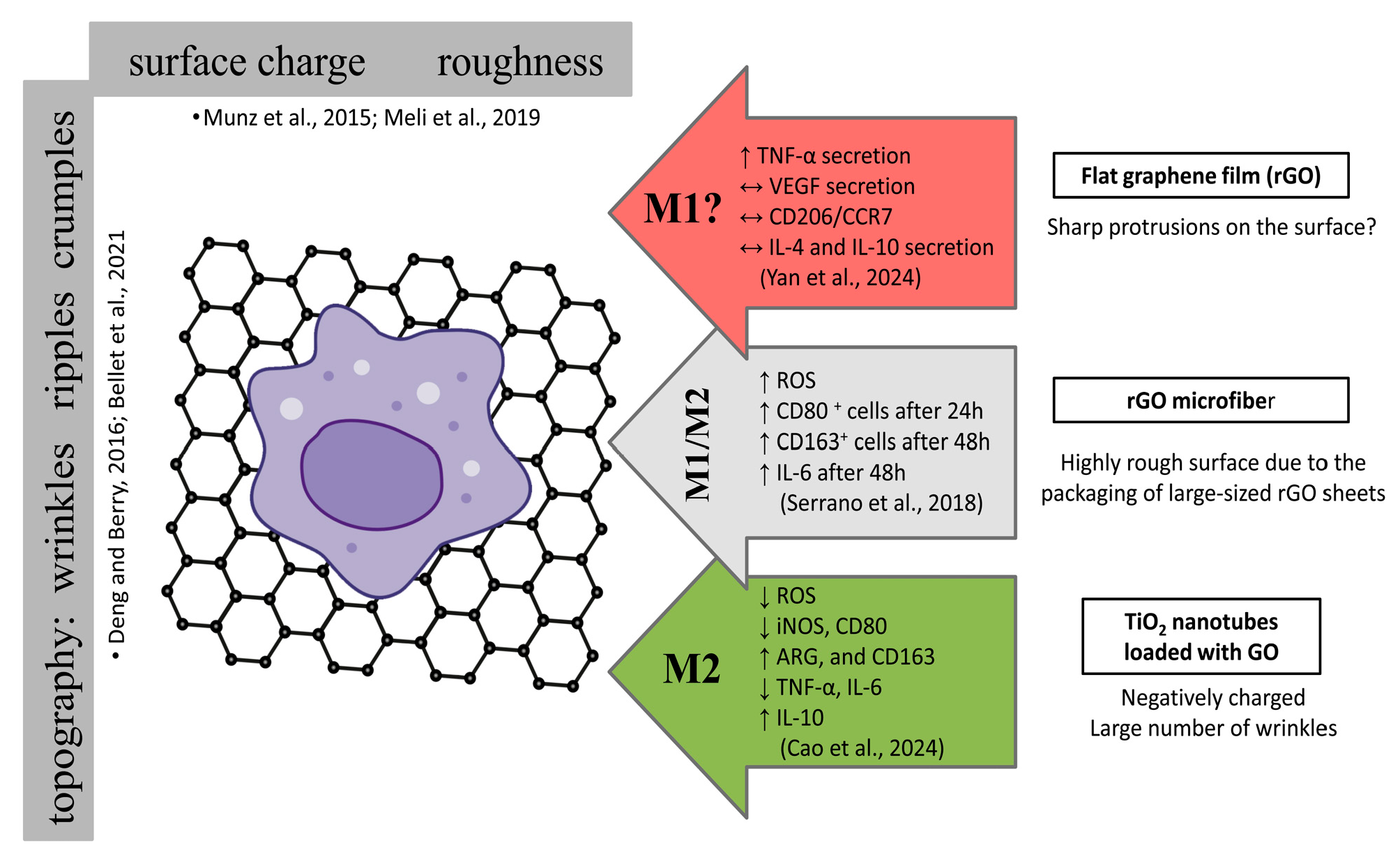

| Graphene free-standing substrate with 20 µm microgrooves | rGO films micropatterned on the surface of a hydrated PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane) only SEM | Synergic electrical stimulation (DC current 1.5 V/cm) and micropatterning and rGO topography | Cytocompatible, significantly reduced cell spreading area and circularity, MØ M2 phenotypic polarization: ↑ CD206/CCR7 ↓ TNF-α and VEGF secretion ↑ IL-4 and IL-10 secretion Suppression of actin polymerization and PI3K signaling pathway. | THP-1 cells | [100] |

| rGO microfibers | GO nanosheets SEM, AFM, XPS | Microfibers and rGO nanotopography | MØ M1 phenotypic polarization after 24 h: CD80 +cells have a more spherical shape MØ M2 phenotypic polarization after 48 h: CD163+ cells have a more elongated shape However, no quantitative analysis was performed to confirm these proportions. Additional information is provided in Figure 8. | RAW 264.7 cells | [99] |

| TiO2 nanotubes loaded with GO | GO was electrodeposited onto the surface of anodised TNT (titanium dioxide nanotubes) SEM, AFM, Raman spectra, water contact angle, XRD (X-ray diffraction) | Nanotubes and GO nanotopography | Cells were round or almost round. Promote M2 polarization by downregulating inflammatory and chemokine genes and reducing NADH dehydrogenase activity, NO levels, and ROS production. Additional information is provided in Figure 8. | RAW264.7 cells | [98] |

| GO-based injectable conductive hydrogel | oxidized hyaluronic acid, N-carboxyethyl chitosan, GO, polymyxin B FITR (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy), SEM, conductivity, swelling, stability, structural integrity | Local electrochemical changes (conductive hydrogel) | Cytocompatible, promoting proliferation Spindle-shaped morphology Antibacterial Promote M2 polarization: ↑ number of M2-type MØ ↑ IL-10 ↓ TNF-α Improve the local inflammation, angiogenesis, accelerating the healing of diabetic wounds. | NIH/3T3 fibroblasts E.coli, S. aureus, Rat Model of Type II Diabetes Mellitus (Sprague–Dawley male rats) | [104] |

5.1. Discrimination of MØ Phenotypic and Sub-Phenotypic States

5.2. MØ Cell Origin (Primary vs. Established Cell Lines)

5.3. Migratory vs. Tissue-Resident MØ

5.4. Differences Between Human and Murine Skin and MØ

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joorabloo, A.; Liu, T. Recent Advances in Nanomedicines for Regulation of Macrophages in Wound Healing. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Boniakowski, A.; Kimball, A.S.; Jacobs, B.N.; Kunkel, S.L.; A Gallagher, K. Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation in Normal and Diabetic Wound Healing. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuninaka, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Ishigami, A.; Nosaka, M.; Matsuki, J.; Yasuda, H.; Kofuna, A.; Kimura, A.; Furukawa, F.; Kondo, T. Macrophage Polarity and Wound Age Determination. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Fal′Ko, V.I.; Colombo, L.; Gellert, P.R.; Schwab, M.G.; Kim, K. A Roadmap for Graphene. Nature 2012, 490, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalbacova, M.; Broz, A.; Kong, J.; Kalbac, M. Graphene Substrates Promote Adherence of Human Osteoblasts and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Carbon 2010, 48, 4323–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasocka, I.; Jastrzębska, E.; Zuchowska, A.; Skibniewska, E.; Skibniewski, M.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Pasternak, I.; Sitek, J.; Kalbacova, M.H. Graphene 2d Platform Is Safe and Cytocompatibile for Hacat Cells Growing under Static and Dynamic Conditions. Nanotoxicology 2022, 16, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Biswas, D.; Pal, D.S.; Miao, Y.; Iglesias, P.A.; Devreotes, P.N. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Membrane Surface Charge Regulates Cell Polarity and Migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 1499–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y.; He, S.; Chai, R. Regulation of Neural Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation by Graphene-Based Biomaterials. Neural Plast. 2019, 2019, 3608386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Shinde, P.A.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Alami, A.H.; Mirzaeian, M.; Yadav, A.; Olabi, A.G. Graphene Synthesis Techniques and Environmental Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasocka, I.; Jastrzębska, E.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Skibniewski, M.; Pasternak, I.; Kalbacova, M.H.; Skibniewska, E.M. The Effects of Graphene and Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cutaneous Wound Healing and Their Putative Action Mechanism. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 2281–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaba, N.I.; Foo, K.L.; Hashim, U.; Tan, S.J.; Liu, W.W.; Voon, C.H. Synthesis of Graphene Oxide Using Modified Hummers Method: Solvent Influence. Procedia Eng. 2017, 184, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, C.; Shi, G. High-Yield Preparation of Graphene Oxide from Small Graphite Flakes Via an Improved Hummers Method with a Simple Purification Process. Carbon 2015, 81, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetayo, A.; Runsewe, D. Synthesis and Fabrication of Graphene and Graphene Oxide: A Review. Open J. Compos. Mater. 2019, 09, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Kausar, A.; Muhammad, B. An Investigation on 4-Aminobenzoic Acid Modified Polyvinyl Chloride/Graphene Oxide and Pvc/Graphene Oxide Based Nanocomposite Membranes. J. Plast. Film Sheeting 2016, 32, 419–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ye, Y.; Xiao, M.; Wu, G.; Ke, Y. Synthetic Routes of the Reduced Graphene Oxide. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 3767–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovich, S.; Dikin, D.A.; Piner, R.D.; Kohlhaas, K.A.; Kleinhammes, A.; Jia, Y.; Wu, Y.; Nguyen, S.T.; Ruoff, R.S. Synthesis of Graphene-Based Nanosheets Via Chemical Reduction of Exfoliated Graphite Oxide. Carbon 2007, 45, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yan, L.; Bangal, P.R. Chemical Reduction of Graphene Oxide to Graphene by Sulfur-Containing Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 19885–19890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Das, S.K. Bio-Reduced Graphene Oxide as a Nanoscale Antimicrobial Coating for Medical Devices. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khawaga, A.M.; Tantawy, H.; Elsayed, M.A.; Abd El-Mageed, A.I.A. Synthesis and Applicability of Reduced Graphene Oxide/Porphyrin Nanocomposite as Photocatalyst for Waste Water Treatment and Medical Applications. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, V.; Lee, N.Y. Reduced Graphene Oxide: Biofabrication and Environmental Applications. Chemosphere 2022, 311, 136934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano-Andazol, I.; Vázquez, N.; Chacón, M.; Sánchez-Avila, R.M.; Persinal, M.; Blanco, C.; González, Z.; Menéndez, R.; Sierra, M.; Fernández-Vega, Á.; et al. Reduced Graphene Oxide Membranes in Ocular Regenerative Medicine. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 114, 111075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suroto, B.J.; Sembiring, H.F.; Fathurrahman, M.T.; Risdiana, R.; Riveli, N.; Hidayat, S.; Syakir, N. The Study of Wettability in Reduced Graphene Oxide Film on Copper Substrate Using Electrostatic Spray Deposition Technique. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1080, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, C.; Abdelkader, A.M.; Alonso, C.; Andrieux-Ledier, A.; Arenal, R.; Azpeitia, J.; Balakrishnan, N.; Banszerus, L.; Barjon, J.; Bartali, R.; et al. Production and Processing of Graphene and Related Materials. 2D Mater. 2020, 7, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, A.; Lee, D.-J.; Park, S.-S. Estimation of Number of Graphene Layers Using Different Methods: A Focused Review. Materials 2021, 14, 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Basko, D.M. Raman Spectroscopy as a Versatile Tool for Studying the Properties of Graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wróblewska, A.; Duzynska, A.; Judek, J.; Stobinski, L.; Zeranska, K.; Gertych, A.; Zdrojek, M. Statistical Analysis of the Reduction Process of Graphene Oxide Probed by Raman Spectroscopy Mapping. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 475201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeranska-Chudek, K.; Wróblewska, A.; Kowalczyk, S.; Plichta, A.; Zdrojek, M. Graphene Infused Ecological Polymer Composites for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding and Heat Management Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kim, T.; Yang, C. Thickness Contrast of Few-Layered Graphene in Sem. Surf. Interface Anal. 2012, 44, 1538–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, T.; Tang, Y.; Luo, G.; Liang, G.; He, W. Epigenetic Regulation of Macrophage Polarization in Wound Healing. Burn. Trauma 2023, 11, tkac057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, G.R.; Almeida, P.P.; de Oliveira Santos, L.D.O.; Rodrigues, L.P.; de Carvalho, J.L.; Boroni, M. Hallmarks of Aging in Macrophages: Consequences to Skin Inflammaging. Cells 2021, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, M.; Sahin, K.B.; West, Z.E.; Murray, R.Z. Macrophage Phenotypes Regulate Scar Formation and Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Nair, M.G. Macrophages in Wound Healing: Activation and Plasticity. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2019, 97, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, E.; Niculite, C.; Lambrescu, I.M.; Gaina, G.; Ioghen, O.; Ceafalan, L.C.; Hinescu, M.E. Macrophages and Stem Cells—Two to Tango for Tissue Repair? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaintreuil, P.; Kerreneur, E.; Bourgoin, M.; Savy, C.; Favreau, C.; Robert, G.; Jacquel, A.; Auberger, P. The Generation, Activation, and Polarization of Monocyte-Derived Macrophages in Human Malignancies. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1178337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in Immunoregulation and Therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Schloss, R.; Palmer, A.; Berthiaume, F. The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-Wound Healing Phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saas, P.; Chagué, C.; Maraux, M.; Cherrier, T. Toward the Characterization of Human Pro-Resolving Macrophages? Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 593300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, L.A.; Wilgus, T.A.; Koh, T.J. Macrophages in Healing Wounds: Paradoxes and Paradigms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willenborg, S.; Injarabian, L.; Eming, S.A. Role of Macrophages in Wound Healing. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2022, 14, a041216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanshahi, A.; Moradzad, M.; Ghalamkari, S.; Fadaei, M.; Cowin, A.J.; Hassanshahi, M. Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation in Skin Wound Healing. Cells 2022, 11, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J.; Allen, J.E.; Biswas, S.K.; Fisher, E.A.; Gilroy, D.W.; Goerdt, S.; Gordon, S.; Hamilton, J.A.; Ivashkiv, L.B.; Lawrence, T.; et al. Macrophage Activation and Polarization: Nomenclature and Experimental Guidelines. Immunity 2014, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, A.; Hao, D.; Barrera, J.; Henn, D.; Lin, S.; Moeinzadeh, S.; Kim, S.; Maloney, W.; Gurtner, G.; Wang, A.; et al. A Bioactive Compliant Vascular Graft Modulates Macrophage Polarization and Maintains Patency with Robust Vascular Remodeling. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 19, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcu, D.U.; Korkmaz, A.; Gunalp, S.; Helvaci, D.G.; Erdal, Y.; Dogan, Y.; Suner, A.; Wingender, G.; Sag, D. Effect of Stimulation Time on the Expression of Human Macrophage Polarization Markers. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265196. [Google Scholar]

- Kerneur, C.; Cano, C.E.; Olive, D. Major Pathways Involved in Macrophage Polarization in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1026954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque-Martin, R.; Mander, P.K.; Leenen, P.J.M.; Winther, M.P.J. Classic and New Mediators for in vitro Modelling of Human Macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 109, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, W.; Mu, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Nie, X. Macrophage Polarization in Diabetic Wound Healing. Burn. Trauma 2022, 10, tkac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the Full Spectrum of Macrophage Activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, K.A.; Amici, S.A.; Webb, L.M.; Ruiz-Rosado, J.D.D.; Popovich, P.G.; Partida-Sanchez, S.; Guerau-de-Arellano, M. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristorena, M.; Gallardo-Vara, E.; Vicen, M.; Casas-Engel, M.d.L.; Ojeda-Fernandez, L.; Nieto, C.; Blanco, F.J.; Valbuena-Diez, A.C.; Botella, L.M.; Nachtigal, P.; et al. Mmp-12, Secreted by Pro-Inflammatory Macrophages, Targets Endoglin in Human Macrophages and Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Gan, S.; Zhu, Q.; Dai, D.; Li, N.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Hou, D.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Q.; et al. Modulation of M2 Macrophage Polarization by the Crosstalk between Stat6 and Trim24. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Xian, D.; Liu, J.; Pan, S.; Tang, R.; Zhong, J. Regulating the Polarization of Macrophages: A Promising Approach to Vascular Dermatosis. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 8148272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Stokes, J.V.; Tan, W.; Pruett, S.B. An Optimized Flow Cytometry Panel for Classifying Macrophage Polarization. J. Immunol. Methods 2022, 511, 113378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizova, Z.; Benesova, I.; Bartolini, R.; Novysedlak, R.; Cecrdlova, E.; Foley, L.K.; Striz, I. M1/M2 Macrophages and Their Overlaps-Myth or Reality? Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 1067–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Cheng, X.; Jin, L.; Shan, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, J. Recent Advances in Strategies to Target the Behavior of Macrophages in Wound Healing. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.-D.; Gao, J.; Tang, A.-F.; Feng, C. Shaping the Immune Landscape: Multidimensional Environmental Stimuli Refine Macrophage Polarization and Foster Revolutionary Approaches in Tissue Regeneration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, H.D.; Trentin, A.G. Skin Wound Healing in Humans and Mice: Challenges in Translational Research. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2018, 90, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colletta, A.D.; Pelin, M.; Sosa, S.; Fusco, L.; Prato, M.; Tubaro, A. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials and Skin: An Overview. Carbon 2022, 196, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, C. Advances in Graphene-Based 2D Materials for Tendon, Nerve, Bone/Cartilage Regeneration and Biomedicine. iScience 2024, 27, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Ma, W.; Huan, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, C. Graphene Oxide/Chitosan/Calcium Silicate Aerogels for Hemostasis and Infectious Wound Healing. Regen. Med. Dent. 2025, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruíz, I.; González, L.; Quiroz, A.; Aguayo, C.; Toledo, J.; Fernández, K. Optimization and Validation of Chitosan-Reduced Graphene Oxide-Pluronic F-127 Hydrogel Synthesis for Potential Wound Dressing. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e02598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Zou, L.; Xu, Z.; Ou, X.; Guo, W.; Gao, Y.; Gao, G. Alginate Foam Gel Modified by Graphene Oxide for Wound Dressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sareło, P.; Wiśniewska-Wrona, M.; Sikora, M.; Mielan, B.; Gerasymchuk, Y.; Wędzyńska, A.; Boiko, V.; Hreniak, D.; Szymonowicz, M.; Sobieszczańska, B.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Graphene Oxide-Enhanced Chitosan Sponges as a Potential Antimicrobial Wound Dressing for Infected Wound Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wen, D.; Deng, Z.; Wu, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Nano-Silver/Graphene Oxide Antibacterial Skin Dressing. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. Advances in Graphene Oxide-Based Polymeric Wound Dressings for Wound Healing. Front. Mater. 2025, 12, 1635502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.F.; Mosser, D.M. A Novel Phenotype for an Activated Macrophage: The Type 2 Activated Macrophage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002, 72, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Ma, C.; Li, J.; You, S.; Dang, L.; Wu, J.; Hao, Z.; Li, J.; Zhi, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. Proteomic Characterization of Four Subtypes of M2 Macrophages Derived from Human Thp-1 Cells. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2022, 23, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, B.; Sun, Y.; Song, W.; Guo, S. Macrophage Origin, Phenotypic Diversity, and Modulatory Signaling Pathways in the Atherosclerotic Plaque Microenvironment. Vessel Plus 2021, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamilos, A.; Winter, L.; Schmitt, V.H.; Barsch, F.; Grevenstein, D.; Wagner, W.; Babel, M.; Keller, K.; Schmitt, C.; Gürtler, F.; et al. Macrophages: From Simple Phagocyte to an Integrative Regulatory Cell for Inflammation and Tissue Regeneration—A Review of the Literature. Cells 2023, 12, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntzel, T.; Bagnard, D. Manipulating Macrophage/Microglia Polarization to Treat Glioblastoma or Multiple Sclerosis. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orecchioni, M.; Ghosheh, Y.; Pramod, A.B.; Ley, K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(Lps+) vs. Classically and M2(Lps–) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, E.A.; Devitt, A.; Johnson, J.R. Macrophages: The Good, the Bad, and the Gluttony. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 708186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönborn, K.; Willenborg, S.; Schulz, J.-N.; Imhof, T.; Eming, S.A.; Quondamatteo, F.; Brinckmann, J.; Niehoff, A.; Paulsson, M.; Koch, M.; et al. Role of Collagen Xii in Skin Homeostasis and Repair. Matrix Biol. 2020, 94, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; Kaur, J.; Wick, P.; Pelin, M.; Tubaro, A.; Carniel, F.C.; Tretiach, M.; Flahaut, E.; Iglesias, D.; et al. Environmental and Health Impacts of Graphene and Other Two-Dimensional Materials: A Graphene Flagship Perspective. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 6038–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Coronel, E.; Ortega, E. Macrophage Polarization Modulates Fcγr- and Cd13-Mediated Phagocytosis and Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Independently of Receptor Membrane Expression. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povo-Retana, A.; Mojena, M.; Boscá, A.; Pedrós, J.; Peraza, D.A.; Valenzuela, C.; Laparra, J.M.; Calle, F.; Boscá, L. Graphene Particles Interfere with Pro-Inflammatory Polarization of Human Macrophages: Functional and Electrophysiological Evidence. Adv. Biol. 2021, 5, 2100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.G.; Mandarino, A.; Koch, B.; Meyer, A.K.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Hirsch, C.; Gemming, T.; Schmidt, O.G.; Liu, Z.; Rümmeli, M.H. Size and Time Dependent Internalization of Label-Free Nano-Graphene Oxide in Human Macrophages. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 1980–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Valle, R.P.; Zuo, Y.Y.; Xia, T.; Liu, S. Crucial Role of Lateral Size for Graphene Oxide in Activating Macrophages and Stimulating Pro-Inflammatory Responses in Cells and Animals. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 10498–10515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, C.; Rivers-Auty, J.; Lemarchand, E.; Vranic, S.; Wang, E.; Buggio, M.; Rothwell, N.J.; Allan, S.M.; Kostarelos, K.; Brough, D. Small, Thin Graphene Oxide Is Anti-Inflammatory Activating Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 Via Metabolic Reprogramming. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 11949–11962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malanagahalli, S.; Murera, D.; Martín, C.; Lin, H.; Wadier, N.; Dumortier, H.; Vázquez, E.; Bianco, A. Few Layer Graphene Does Not Affect Cellular Homeostasis of Mouse Macrophages. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Bussche, A.v.D.; Creighton, M.; Hurt, R.H.; Kane, A.B.; Gao, H. Graphene Microsheets Enter Cells through Spontaneous Membrane Penetration at Edge Asperities and Corner Sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12295–12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiga, Á.; Lin, H.; Bianco, A. Interaction of Industrial Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes with Human Primary Macrophages: Assessment of Nanotoxicity and Immune Responses. Carbon 2024, 223, 119024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicuéndez, M.; Casarrubios, L.; Barroca, N.; Silva, D.; Feito, M.J.; Diez-Orejas, R.; Marques, P.A.A.P.; Portolés, M.T. Benefits in the Macrophage Response Due to Graphene Oxide Reduction by Thermal Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, B.; Yin, N.; Gao, X.; Xia, T.; Chen, J.-J.; et al. Graphene Oxide Induces Toll-Like Receptor 4 (Tlr4)-Dependent Necrosis in Macrophages. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 5732–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavín-López, M.d.P.; Torres-Torresano, M.; García-Cuesta, E.M.; Soler-Palacios, B.; Griera, M.; Martínez-Rovira, M.; Martínez-Rovira, J.A.; Rodríguez-Puyol, D.; de Frutos, S. A Graphene-Based Bioactive Product with a Non-Immunological Impact on Mononuclear Cell Populations from Healthy Volunteers. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Ji, D.K.; Lucherelli, M.A.; Reina, G.; Ippolito, S.; Samorì, P.; Bianco, A. Comparative Effects of Graphene and Molybdenum Disulfide on Human Macrophage Toxicity. Small 2020, 16, e2002194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebre, F.; Boland, J.B.; Gouveia, P.; Gorman, A.L.; Lundahl, M.L.; Lynch, R.I.; O’Brien, F.J.; Coleman, J.; Lavelle, E.C. Pristine Graphene Induces Innate Immune Training. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 11192–11200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korejwo, D.; Chortarea, S.; Louka, C.; Buljan, M.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Wick, P.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T. Gene Expression Profiling of Human Macrophages after Graphene Oxide and Graphene Nanoplatelets Treatment Reveals Particle-Specific Regulation of Pathways. NanoImpact 2023, 29, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, K.; Li, W.; Yang, N.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wei, T. The Interactions between Pristine Graphene and Macrophages and the Production of Cytokines/Chemokines Via Tlr- and NF-κB-Related Signaling Pathways. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6933–6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feito, M.J.; Diez-Orejas, R.; Cicuéndez, M.; Casarrubios, L.; Rojo, J.M.; Portolés, M.T. Characterization of M1 and M2 Polarization Phenotypes in Peritoneal Macrophages after Treatment with Graphene Oxide Nanosheets. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2019, 176, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Berry, V. Wrinkled, Rippled and Crumpled Graphene: An Overview of Formation Mechanism, Electronic Properties, and Applications. Mater. Today 2016, 19, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbacova, M.H.; Verdanova, M.; Broz, A.; Vetushka, A.; Fejfar, A.; Kalbac, M. Modulated Surface of Single-Layer Graphene Controls Cell Behavior. Carbon 2014, 72, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasocka, I.; Skibniewska, E.; Skibniewski, M.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Jastrzębska, E.; Pasternak, I.; Jakub, S.; Hubalek-Kalbacova, M. Graphene Monolayer as an Appropriate Substrate for Mesenchymal Stem Cells Support in Regenerative Medicine. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2023, 61, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasocka, I.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Skibniewski, M.; Skibniewska, E.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.; Pasternak, I.; Kalbacova, M.H. Cytocompatibility of Graphene Monolayer and Its Impact on Focal Cell Adhesion, Mitochondrial Morphology and Activity in Balb/3t3 Fibroblasts. Materials 2021, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasocka, I.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Skibniewski, M.; Skibniewska, E.; Strupinski, W.; Pasternak, I.; Kmieć, H.; Kowalczyk, P. Biocompatibility of Pristine Graphene Monolayer: Scaffold for Fibroblasts. Toxicol. Vitr. 2018, 48, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, P.; Gasparotto, M.; Pressi, S.; Fortunato, A.; Scapin, G.; Mba, M.; Menna, E.; Filippini, F. Graphene-Based Scaffolds for Regenerative Medicine. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munz, M.; Giusca, C.E.; Myers-Ward, R.L.; Gaskill, D.K.; Kazakova, O. Thickness-Dependent Hydrophobicity of Epitaxial Graphene. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 8401–8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, V.S.; Veerasubramanian, P.K.; Atcha, H.; Reitz, Z.; Downing, T.L.; Liu, W.F. Biophysical Regulation of Macrophages in Health and Disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 106, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Luo, B.; Mu, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, R.; Yao, Y.; Chen, S. The Regulatory Effect of TiO2 nanotubes Loaded with Graphene Oxide on Macrophage Polarization in an Inflammatory Environment. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.C.; Feito, M.J.; González-Mayorga, A.; Diez-Orejas, R.; Matesanz, M.C.; Portolés, M.T. Response of Macrophages and Neural Cells in Contact with Reduced Graphene Oxide Microfibers. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Qian, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Li, L. Synergistic Effects of Graphene Microgrooves and Electrical Stimulation on M2 Macrophage Polarization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 711, 149911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, F.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Heng, B.C.; Xie, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Ding, S.; Liu, F.; et al. Matrix Stiffness Regulates Macrophage Polarisation Via the Piezo1-Yap Signalling Axis. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, P.C.; Pan, Y.L.; Liang, Z.Q.; Yang, G.L.; Wu, C.J.; Zeng, L.; Wang, L.N.; Sun, J.; Liu, M.M.; Yuan, Y.F.; et al. Mechanical Stretch Promotes Macrophage Polarization and Inflammation Via the Rhoa-Rock/Nf-Κb Pathway. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 6871269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, M.; Chen, C. Development of Biomaterials to Modulate the Function of Macrophages in Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Guan, L.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Guo, D.; Li, R.; Zvyagin, A.V.; Lin, Q.; Qu, W. Graphene Oxide-Based Injectable Conductive Hydrogel Dressing with Immunomodulatory for Chronic Infected Diabetic Wounds. Mater. Des. 2022, 224, 111284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.J.; Tsang, T.M.; Qiu, Y.; Dayrit, J.K.; Freij, J.B.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Olszewski, M.A. Macrophage M1/M2 Polarization Dynamically Adapts to Changes in Cytokine Microenvironments in Cryptococcus Neoformans Infection. mBio 2013, 4, e00264–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezouar, S.; Mege, J.-L. New Tools for Studying Macrophage Polarization: Application to Bacterial Infections. In Macrophages; Prakash, H., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Hardie, J.; Landis, R.F.; Mas-Rosario, J.A.; Chattopadhyay, A.N.; Keshri, P.; Sun, J.; Rizzo, E.M.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Farkas, M.E.; et al. High-Content and High-Throughput Identification of Macrophage Polarization Phenotypes. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 8231–8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Tan, K.; Wang, R.; Jia, L.; Li, W. Macrophages with Different Polarization Phenotypes Influence Cementoblast Mineralization through Exosomes. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 2022, 4185972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, M.H.M.; Hauck, F.; Dreyer, J.H.; Kempkes, B.; Niedobitek, G. Macrophage Polarisation: An Immunohistochemical Approach for Identifying M1 and M2 Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. Rna-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, B.; Belk, J.A.; Meier, S.L.; Chen, A.Y.; Sandor, K.; Czimmerer, Z.; Varga, Z.; Bene, K.; Buquicchio, F.A.; Qi, Y.; et al. Macrophage Inflammatory and Regenerative Response Periodicity Is Programmed by Cell Cycle and Chromatin State. Mol. Cell 2022, 83, 121–138.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Pal, R. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptomic and Proteomic Data. Curr. Genom. 2013, 14, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Jhong, J.-H.; Chen, Q.; Huang, K.-Y.; Strittmatter, K.; Kreuzer, J.; DeRan, M.; Wu, X.; Lee, T.-Y.; Slavov, N.; et al. Global Characterization of Macrophage Polarization Mechanisms and Identification of M2-Type Polarization Inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S.; Takano, R.; Tamura, S.; Tani, S.; Iwaizumi, M.; Hamaya, Y.; Takagaki, K.; Nagata, T.; Seto, S.; Horii, T.; et al. M2 Polarization of Murine Peritoneal Macrophages Induces Regulatory Cytokine Production and Suppresses T-Cell Proliferation. Immunology 2016, 149, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zogbi, C.; Oliveira, N.C.; Levy, D.; Bydlowski, S.P.; Bassaneze, V.; Neri, E.A.; Krieger, J.E. Beneficial Effects of Il-4 and Il-6 on Rat Neonatal Target Cardiac Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herb, M.; Schatz, V.; Hadrian, K.; Hos, D.; Holoborodko, B.; Jantsch, J.; Brigo, N. Macrophage Variants in Laboratory Research: Most Are Well Done, But Some are RAW. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1457323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, G.; Yamauchi, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Ueki, K. Preparation and Culture of Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages from Mice for Functional Analysis. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.A.; Ginhoux, F.; Yona, S. Monocytes, Macrophages, Dendritic Cells and Neutrophils: An Update on Lifespan Kinetics in Health and Disease. Immunology 2021, 163, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, S.L.; Kumari, S.; Kaur, S.; Khosrotehrani, K. Macrophages in Skin Wounds: Functions and Therapeutic Potential. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souci, L.; Denesvre, C. 3D Skin Models in Domestic Animals. Veter. Res. 2021, 52, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, A.; Veenstra, J.; Ozog, D.M.; Mi, Q.-S. The Roles of Skin Langerhans Cells in Immune Tolerance and Cancer Immunity. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Sacks, D.L. Resilience of Dermis Resident Macrophages to Inflammatory Challenges. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, E.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Kierdorf, K.; Schlitzer, A. Tissue-Specific Macrophages: How They Develop and Choreograph Tissue Biology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu, M.; Constantin, C.; Jugulete, G.; Cauni, V.; Dubrac, S.; Szöllősi, A.G.; Zurac, S. Langerhans Cells—Revising Their Role in Skin Pathologies. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Liu, N.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, W.; Kuang, Y.; Chen, X.; Peng, C. The Role of Langerhans Cells in Epidermal Homeostasis and Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 11646–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, M.; Paolini, L.; Vinatier, E.; Mantovani, A.; Delneste, Y.; Jeannin, P. Antitumor Strategies Targeting Macrophages: The Importance of Considering the Differences in Differentiation/Polarization Processes between Human and Mouse Macrophages. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltavets, A.S.; Vishnyakova, P.A.; Elchaninov, A.V.; Sukhikh, G.T.; Fatkhudinov, T.K. Macrophage Modification Strategies for Efficient Cell Therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschaler, J.; Schlorke, D.; Arnhold, J. Differences in Innate Immune Response between Man and Mouse. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 34, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhu, N.; Qiu, Y.; Tan, J.; Wang, F.; Qin, L.; Dai, A. Resistin-Like Molecules: A Marker, Mediator and Therapeutic Target for Multiple Diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, J.D.; Diotallevi, M.; Nicol, T.; McNeill, E.; Shaw, A.; Chuaiphichai, S.; Hale, A.; Starr, A.; Nandi, M.; Stylianou, E.; et al. Nitric Oxide Modulates Metabolic Remodeling in Inflammatory Macrophages through Tca Cycle Regulation and Itaconate Accumulation. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 218–230.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material | Material Composition | Material Properties | Activity | In Vitro | In Vivo | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO/Chitosan/Amorphous Calcium Silicate (GC-CS) Aerogel and GO/Chitosan/Calcium Silicate Nanofiber (GC-nfCS) Aerogel | GO, chitosan, calcium silicate aerogels | High liquid absorption capacity (much higher in GC-nfCS but with reduced elasticity and shape retention ability in the wet state) | Good blood compatibility, coagulation, and hemolysis capacity Hemostatic Antibacterial (with photothermal therapy) Wound healing abilities | Rat blood | Rat liver bleeding model BALB/c mice (S. aureus bacterial suspension to the wound site) | [59] |

| Chitosan-rGO-Pluronic F-127 Hydrogel | rGO, chitosan, pluronic F127 (poloxamer 407) | Hydrogel with high mechanical properties, fluid absorption, and conductivity | Antibacterial Enhanced cell migration Enhanced re-epithelialization and vascularization | E.coli, S aureus, Human dermal fibroblasts | Male Yorkshire pigs | [60] |

| Alginate foam gel modified by GO | Chitooligosaccharide modified with GO nanocomposite (CG), calcium alginate foam substrate | Foam with high mechanical properties, good water absorption, and stability | Cytocomaptible Antibacterial properties Rapid hemostasis, reducing the inflammatory response and promoting vascular remodeling | NIH/3T3 S. aureus | Sprague–Dawley rats | [61] |

| GO-enhanced chitosan sponge | GO, microcrystalline chitosan, glycerin | Sponge with significant reduction in elasticity after material sterilization; good sorption and absorption properties | Cytocompatible; Antibacterial but not antifungal | L929 fibroblasts E.coli, S aureus, C. albicans | [62] | |

| Nano-silver/GO skin dressing | Ag, GO, gelatin/sodium polyacrylate/kaolin mixture | Hydrogel with good water vapor permeability, high mechanical properties | Infrared bacterial inhibition | E. coli | [63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lasocka, I.; Skibniewski, M.; Pasternak, I.; Wróblewska, A.; Biernacka, Z.; Skibniewska, E.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Kalbacova, M.H. Graphene and Its Derivatives as Modulators of Macrophage Polarization in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Cells 2025, 14, 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242001

Lasocka I, Skibniewski M, Pasternak I, Wróblewska A, Biernacka Z, Skibniewska E, Szulc-Dąbrowska L, Kalbacova MH. Graphene and Its Derivatives as Modulators of Macrophage Polarization in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Cells. 2025; 14(24):2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242001

Chicago/Turabian StyleLasocka, Iwona, Michał Skibniewski, Iwona Pasternak, Anna Wróblewska, Zuzanna Biernacka, Ewa Skibniewska, Lidia Szulc-Dąbrowska, and Marie Hubalek Kalbacova. 2025. "Graphene and Its Derivatives as Modulators of Macrophage Polarization in Cutaneous Wound Healing" Cells 14, no. 24: 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242001

APA StyleLasocka, I., Skibniewski, M., Pasternak, I., Wróblewska, A., Biernacka, Z., Skibniewska, E., Szulc-Dąbrowska, L., & Kalbacova, M. H. (2025). Graphene and Its Derivatives as Modulators of Macrophage Polarization in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Cells, 14(24), 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242001