1. Introduction

Mechanosensitive ion channels have been identified to play critical roles in the modulation of cellular signals, thus affecting growth, differentiation, and functions, including those of blood cells [

1,

2,

3]. Interestingly, the growth and differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the bone marrow niche is mainly governed by molecular and signaling crosstalk between mechanosensors and extracellular matrix components [

4,

5]. Piezo1 is a cation channel that regulates cellular Ca

2+ influx in response to forces derived from cell–cell, cell–matrix, and shear stress-mediated interactions [

6,

7]; this channel consists of a large three-blade propeller-shaped transmembrane protein encoded by the

FAM38A gene, found to be activated by various extracellular stimuli, such as fluid shear stress, osmotic pressure, matrix stiffness, or cell density [

7]. Additionally, Piezo1 overexpression and activation have been reported to be altered in various cell types and pathologies, thus validating its regulatory role in various cellular and physiological responses [

3,

8]. Piezo1-mediated Ca

2+ signaling and activation of different kinases have been found to have regulatory effects in various cellular processes [

9].

Particular to blood cell types, gain-of-function studies revealed that Piezo1 acts as a mediator for hereditary xerocytosis (HX), where dehydration of red blood cells occurs due to increased intracellular Ca

2+ influx, thus resulting in hemolytic anemia [

10]. Similarly, a retrospective study of 126 individuals diagnosed with Piezo1-HX pointed to high variability in the clinical expression of Piezo1 mutation with clinical manifestations that include anemia, splenomegaly, and post-splenectomy thrombosis [

11]. Notably, functional aspects of Piezo1 are not limited to erythropoiesis since it was recently found to affect the megakaryocytic lineage also [

12,

13]. Herein, megakaryocytes (MKs), which are platelet progenitors, express Piezo1 and its expression has been found to be significantly upregulated in primary myelofibrosis (PMF), a disease characterized by enhanced bone marrow fibrosis and stiffness of extracellular matrix (ECM) [

13]. Moreover, in human CD34+ cells and mouse MKs, Piezo1 activation has been reported to downregulate MK ploidy and platelet biogenesis [

12,

14]. Recently, Demagny et al. identified novel roles of Piezo1 in megakaryopoiesis, where pharmacological activation of Piezo1 induces cytosolic Ca

2+ ion influx and reduced MK maturation (CD41+CD42+ count depleted) [

12].

In a recent study, we used pharmacological approaches as well as MK-specific double-knockout (KO) Piezo1/Piezo2 mice to show the importance of this family of proteins in maintaining normal platelet levels (platelet biogenesis) [

13]. In the present study, we aimed at identifying the specific roles of MK Piezo1 in determining MK and platelet levels and function using a newly developed mouse line in which Piezo1 is deleted in cells where PF4-Cre is active, particularly the MKs. Collectively, our findings point to MK/platelet Piezo1 as a direct regulator of platelet levels and activation, and surprisingly, also of some inflammatory cytokines and blood cell count profiles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Transgenic Mouse Models

For the generation of PF4-Cre

+/+Piezo1

fl/fl homozygous transgenic mice, C57BL/6-Tg(Pf4-icre)Q3Rsko/J mice (Jackson Laboratories), designated as PF4-Cre

+/+, and B6.Cg-Piezo1tm2.1Apat/J mice (Jackson Laboratories), designated as Piezo1

fl/fl, were obtained and used in this study [

15]. PF4-Cre

+/+ transgenic mice express a codon-improved Cre recombinase (iCre) under the control of mouse platelet factor 4 (

Pf4) gene promoter. Piezo1

fl/fl mice have inserted LoxP sites between exons 20 and 23 of the mouse

Piezo1 gene. Two breeding cycles were performed, where from the first cycle PF4-Cre

+/−Piezo1

fl/− heterozygous mice were obtained, which were further crossbred in the second cycle to generate the double-homozygous PF4-Cre

+/+Piezo1

fl/fl mice (detailed in

Supplementary Figure S1). In this transgenic mouse model, the

Piezo1 gene is deleted in MKs as well as in hematopoietic progenitor cells. Mouse colonies were housed at 20–22 °C on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water. All protocols were approved by the Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.2. Primary Mouse Bone Marrow Culture and Western Blot Analysis

Bone marrow from PF4-Cre

+/+ and Piezo1 KO (PF4-Cre

+/+Piezo1

fl/fl) mice (2 males and 2 females from each genotype per each experiment, with a total of 8-10 mice analyzed) was flushed from the femurs and tibia using a 23-gauge needle and 10 mL CATCH buffer (consisting of Hank’s balanced salt solution, 0.38% sodium citrate, 1 mM adenosine, 1 mM theophylline, and 5% fetal bovine serum). Collected cells were suspended in CATCH buffer and centrifuged for 5 min at 300×

g at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and cells were resuspended in 10 mL of CATCH buffer and filtered through a 100 µm cell strainer to remove any cell debris. Cells were counted using a Neubauer chamber and cultured (37 °C, 5% CO

2) in a 6-well plate (Falcon Corning,

Cat#353046), with a density of 10

7 cells/mL, in IMDM media (Invitrogen,

Cat#21056) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum, 1000 IU/mL penicillin, and 1000 µg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen,

Cat#15070-063) as well as 25 ng/mL recombinant TPO (human PEG-rhMGDF, a gift from Kirin Pharma Company, Tokyo, Japan). MKs were purified after 4 days of culture, using a two-step bovine serum albumin (BSA) gradient, as described earlier [

16]. Briefly, total BM cells were suspended in serum-free minimum essential medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Cat#11095080) and thereafter layered on top of a BSA gradient (upper 1.5%, and lower 3% BSA (

w/

v) solution) in a 15 mL conical tube. Afterwards, MKs were separated using gravity flow, then collected and rinsed twice by centrifugation with pre-warmed (37 °C) Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for downstream application. While the purity based on cell number ranges between 50 and 70%, it is likely close to 80–90% based on MK protein and mRNA, as the gradient collects large-size, high-ploidy MKs.

For the immunoblotting of Piezo1, purified MKs were lysed for total protein extraction in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (25 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with 1× concentration of proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#78429) with a 30 min incubation on ice. Extracted protein was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#23225). Moreover, a 1× concentration of SDS loading buffer was added to each sample and then normalized for an equal amount of protein in each sample. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis (4–12% polyacrylamide gel; BioRad, Cat#4561096), followed by transfer onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked for 1 Hr at room temperature (RT) with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk solution, prepared in 1× TBST (TBS buffer with 0.1% Tween−20; 20 mM Tris and 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) and subsequently subjected to overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies. Primary antibodies against mouse Piezo1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#MA5-32876) were used in a dilution of 1:1000, whereas anti-β-actin antibodies (Sigma, Cat#A5441) were used in a dilution of 1:10000, respectively. Upon overnight incubation, the membrane was washed with 1× TBST and incubated for the next 1 Hr with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled anti-Mouse IgG antibodies (Cell Signaling, Cat#7076S) at a dilution of 1:5000. All primary and secondary antibody solutions were made in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1× TBST. The membrane was thereafter probed with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, Cat#WBKLS0100) and bands were visualized using the chemiluminescence detection system ImageQuant LAS4000 (GE Healthcare Bio_Science Corp. Piscataway, NJ, USA).

2.3. mRNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from WBCs and the BSA-gradient-purified MKs, following standard protocols and using Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Kits (Zymo Research,

Cat#R2051). A total of 1 µg RNA was used for complementary DNA (cDNA) preparation with a Quantitect Reverse Transcription cDNA kit (Qiagen,

Cat#205311). TaqMan probes for Piezo1 (Mm01241549_m1) and GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1; housekeeping) were used as commercially available at Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA. For quantitative real-time PCR analysis, samples were run on an ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The obtained CT values were normalized to housekeeping GAPDH CT values. Using the ∆∆CT method, the relative expression of a target gene was determined by following the protocol and 2

−∆∆CT equation [

17]. All probes were predesigned for TaqMan assays and purchased from Applied Biosystems, USA.

2.4. Megakaryocyte Number and Ploidy Analysis

The quantification of mature and immature MKs in BM cells isolated from PF4-Cre

+/+ and PF4-Cre

+/+Piezo1

fl/fl mice was performed using flow cytometry and the standard protocol detailed earlier [

18]. As mentioned above, cells from mouse primary bone marrow cultures after day 4 were collected and rinsed twice with ice-cold 1× PBS. Cells were thereafter stained for their viability using a Zombie Aqua probe (BioLegend,

Cat#423102) at a 1:200 dilution and incubation of 15 min at room temperature (RT). Subsequently, cells were stained with the phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody (eBioscience,

Cat#12-0411-83) and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD42 antibody (Invitrogen,

Cat#17042182) at 1:200 dilutions, with incubation for 15 min at RT. Immature MK counts were identified by gating the CD41

+CD42

− cells, while mature MK counts were quantified by gating the CD41

+CD42

+ cells. To analyze the ploidy state of MKs in these samples, cells were rinsed with ice-cold 1× PBS and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol. Afterwards, cells were stained for 15 min at RT with a 1:200 dilution of FITC-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody (BD Bioscience,

Cat#553848). Right before the analysis, RNAse A (Sigma,

Cat#

R6513) at 0.1 mg/mL and propidium iodide (Sigma,

Cat#

P4170) at 0.05 mg/mL were added to these samples, respectively. All samples were run on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Bioscience), and data were collected using FACSDIVA

TM software (v9.0) and analyzed with FlowJo software version 10.8.1 (BD Biosciences, USA).

2.5. Peripheral Blood Count in Mice

Peripheral blood from PF4-Cre

+/+ and PF4-Cre

+/+Piezo1

fl/fl mice (males and females between 12 and 20 weeks old, n = 37 and n = 35, respectively) was withdrawn via the retro-orbital plexus bleeding method using a heparinized capillary tube under isoflurane anesthesia [

19]. Blood parameters were measured in these blood samples using a Hemavet HV950FS hematology automated counter (Drew Scientific, Waterbury, CT, USA).

2.6. Quantification of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Population

Bone marrow from PF4-Cre+/+ and PF4-Cre+/+Piezo1fl/fl mice (males and females between 15 and 25 weeks old, n = 10 and n = 12, respectively) was isolated, and samples were prepared for flow cytometric analysis, as mentioned above. For HSC populations (LSK, LT-HSC, ST-HSC, MPP2, MPP3/4, MKP, and CD41+) analysis, BM cells were stained with a cocktail of lineage-specific markers, viz., anti-B220 (BD Pharmingen, Cat#552094), anti-CD11b (BD Pharmingen, Cat#557657), anti-Ter119 (BD Pharmingen, Cat#560509), all conjugated with the same fluorochrome APC-Cy7. Further staining with the stem cell markers, viz., anti-Sca-1-PerCP-cy5.5 (Invitrogen, Cat#45-5981-82), anti-c-kit-BV421 (BD Pharmingen, Cat#562609), anti-CD150-APC (Invitrogen, Cat#17-1502-80), anti-CD48-PE (Invitrogen, Cat#12-0481-82), anti-CD41-BV510 (BD Pharmingen, Cat#740136), and Zombie-NIR (viability-specific), in a dilution of 1:200 for all the antibodies. Following incubation for 15 min at RT and protected from direct light, samples were analyzed on a five-laser Aurora (Cytek) flow cytometer. The collected data were analyzed with FlowJo software (version 10.8.1) from BD Biosciences, USA.

2.7. Inflammatory Cytokine Measurement

Baseline measurement of inflammatory cytokines in the serum samples derived from PF4-Cre+/+ and PF4-Cre+/+Piezo1fl/fl mice (n = 9–14; both males and females) was measured by collecting the blood from mice using standard protocols mentioned above. Inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α; Cat#2673KI, IL-6; Cat#2653KI, and IFN-γ; Cat#2612KI) in the serum samples were quantified by using the commercially available mouse-specific ELISA kits, supplied from BD Biosciences, USA. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, quantification of cytokines was performed using standard curves prepared from cytokine standards supplied with the kits. Furthermore, to estimate the innate immune potential of PF4-Cre+/+ and PF4-Cre+/+Piezo1fl/fl mice, mice were challenged with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg (prepared in normal saline). Blood was collected from mice through the retro-orbital plexus bleeding method, at 3 h and 24 h interval after the LPS challenge. Using standard protocols, serum was prepared and stored at −80 °C for the analysis of serum inflammatory cytokines.

Similarly, inflammatory cytokines in the BM and MK culture supernatants were also measured. BM cells were procured and cultured in vitro in similar conditions as mentioned above (

Section 2.2). After the 4th day, BM cells were collected and centrifuged at 300×

g for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected in a separate tube and stored at −80 °C for further quantification of inflammatory cytokines. Cells were washed once with ice-cold 1× PBS and re-suspended in CATCH buffer for a two-step bovine serum albumin (BSA) gradient-based separation of MKs, as described above. Isolated MKs were counted using a Neubauer chamber (Falcon Corning,

Cat#480200) and re-seeded in a 24-well plate, with a density of 2 × 10

4 cells/mL in IMDM media. Following 24 h of incubation, cells were collected along with the culture supernatant and centrifuged at 300×

g for 5 min at 4 °C to collect the culture supernatant and MKs, separately. Supernatant was used for the quantification of inflammatory cytokines, and MKs were used for the isolation of total RNA, cDNA synthesis, and mRNA expression analysis of inflammatory genes using qRT-PCR.

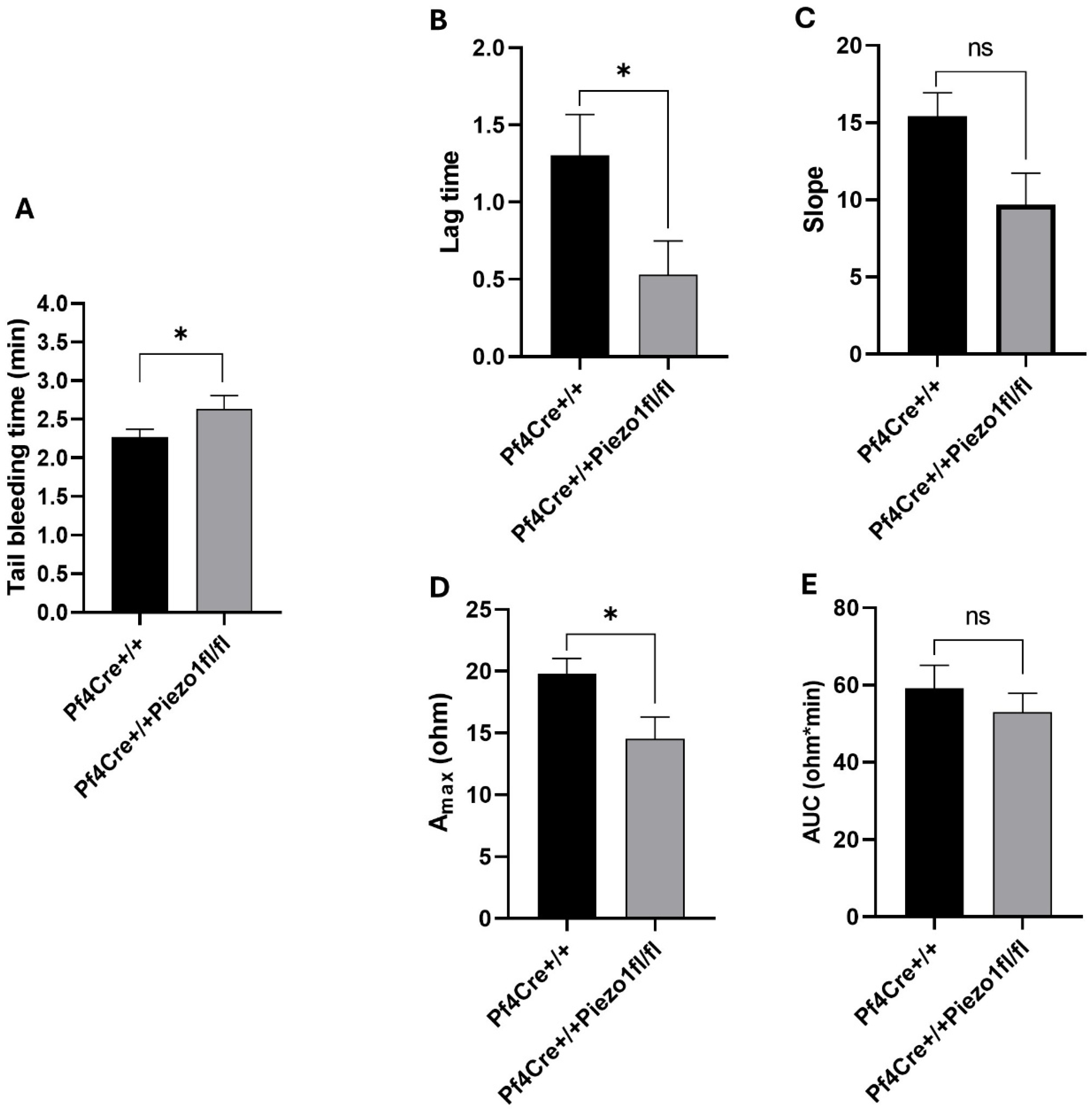

2.8. Measurement of Tail Bleeding Time

PF4-Cre

+/+ and PF4-Cre

+/+Piezo1

fl/fl mice (n = 12; both males and females) were randomly selected and anesthetized using isoflurane anesthesia, and the tail bleeding experiment was performed by following the standard protocol [

20]. Mice were placed on a heat pad and 3 mm of the tail tip was cut with a scalpel and immersed immediately in saline (0.9% NaCl) at 37 °C in a 50 mL conical tube. Time for bleeding and cessation of blood stream was measured and recorded for each mouse. Absence of bleeding for 1 min was considered as complete cessation whereas total time for recording was 20 min from of the tip of the tail, including partial cessations that resume within 1 min.

2.9. Whole Blood Platelet Aggregation Assay

Platelet aggregation was evaluated using whole-blood impedance aggregometry (Model 700; Chrono-Log Corporation, Havertown, PA, USA), as previously described [

21,

22]. In brief, citrated whole blood (200 μL) was mixed with normal saline (800 μL) in a disposable cuvette (Chrono-Log Corporation, Havertown, PA, USA). An electrode was immersed in the sample, and platelet aggregation was measured based on the increase in electrical impedance (mms) caused by platelet clumping on the electrode surface. In vitro platelet activation was induced using mouse-derived collagen (5 μg/mL) and thrombin (0.025 U/mL) (Chrono-Log Corporation, PA, USA). The aggregation reaction was monitored for 6 min at 37 °C with a stirring speed of 1200 rpm. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Aggrolink-8 software (Chrono-Log), and results are expressed as area under the curve (AUC; ohmxminute), lag time (minutes), slope, and maximum aggregation (A

max; ohm).

2.10. Quantitative Expression Analysis of Inflammatory Genes

Total RNA extraction was performed by following the cDNA synthesis using an Invitrogen Thermoscript™ RT-PCR kit by following the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the following TaqMan gene expression primers and probes, purchased from Applied Biosystems with detailed assay IDs: interleukin-6 (Mm00446190_m1), tumor necrosis factor-α (Mm00443258_m1), interferon-γ (Mm01168134_m1), and 18s rRNA (Mm04277571_s1). PCR reaction efficiency and primer concentration were optimized, and qRT-PCR was performed with a ViiA 7 RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystem, Thermo Fisher, USA). The relative expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ mRNA was normalized to the amount of 18sRNA in the same samples, using the relative quantification of the ∆∆CT method mentioned above. Relative expression of the target gene was expressed as the fold change in the target gene, corresponding to its internal housekeeping control.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SE values of three experiments performed in triplicate. A two-tailed Student’s “t” test was used for the statistical analysis, comparing two experimental groups. One-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for the comparison of a single factor in multiple groups. GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software) was used for the statistical analysis and graphing. p values of *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Mechanosensors play a crucial role in the interactions of cells within the bone marrow microenvironment, affecting the differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells, which in turn have vital physiological outcomes [

3,

4]. MK lineage commitment, polyploidy, and proplatelet formation are also regulated by various mechanosensors, where we have recently identified Piezo1 as a regulator of MK development in culture [

5,

25]. Herein, under in vitro conditions, pharmacological activation of Piezo1 using Yoda1 (a known pharmacological activator) resulted in a significant increase in the number of immature MKs (CD41

+CD42

− cells), along with a lower number of mature MKs (CD41

+CD42

+) [

13]. Similarly, Demagny et al. studied the mechanical activation of Piezo1 using Yoda1 in cultured MKs and found reduced MK maturation and count [

12]. These changes were reverted when

Piezo1 gene expression was suppressed using an shRNA-silencing approach [

12]. While these studies suggested a regulatory role of Piezo1 in MK development, they are limited to in vitro findings, especially under pharmacological modulations.

To validate these initial findings and identify the putative role(s) of Piezo1 in BM hematopoiesis, we generated mice with deletion of Piezo1 in the megakaryocytic (MK) lineage and HSC progenitors using PF4-Cre mice cross breed with Piezo1

fl/fl mice to yield PF4-Cre

+/+Piezo1

fl/fl homozygous mice (Piezo1 KO). Recently, Piezo1 has been identified as an early regulator of hematopoiesis [

26], thus validating our findings concerning the tendency of PF4-Cre-targeted deletion of Piezo1 to affect the level of hematopoietic progenitors. Interestingly, in our study, Piezo1 KO mice did not exhibit any significant difference in the number of mature MKs (CD41

+CD42

+) or in the ploidy level compared to PF4-Cre control mice; this discrepancy with in vitro studies might be due to the presence of compensatory mechanism(s) within a more physiological in vivo milieu. In this context, we ruled out a compensatory effect of Piezo2, as its mRNA level was negligible or not detected in repeated assays of MKs derived from control mice or Piezo1 KO mice. Additionally, it is possible that Piezo1 deletion might not have the opposite effect than that of its activation, owing to saturation effects. Piezo1 overexpression and altered megakaryopoiesis have also been reported in primary myelofibrosis (PMF), marked by increased MK number and bone marrow stiffness [

13,

27]. Herein, altered matrix stiffness might contribute to augmenting Piezo1 expression and, hence, its activation, which could lead to changes in MK maturation [

13]. In our current study, bone marrow matrix stiffness was not found to be altered in the Piezo1 KO mice (as per reticulin staining), as compared to their matching controls. Hence, MK maturation and polyploidization remained unaffected upon Piezo1 deletion, in agreement with a previous report [

28].

In our study, MK-specific Piezo1 deletion resulted in an approximately 25% increase in platelet count in mice, while there was no parallel increase in MK number to account for this observation. It is possible that reduced vascular adhesion potential of platelets upon Piezo1 deletion manifests in augmenting their level in the circulation. Tail bleeding time estimated in Piezo1 KO mice was slightly higher compared to controls. Also, platelet activation mediated by collagen was found to be reduced in the KO mice, thus validating the measurements of somewhat prolonged tail bleeding in these mice. Our findings are in line with the reported reduced severity of arterial thrombosis and stroke in hypertensive mice upon pharmacological inhibition of Piezo1 [

29]. Further, Aglialoro et al. reported that activation of Piezo1 leads to enhanced adhesion of platelets to VCAM1 and fibronectin, thus resulting in integrin activation and thrombus formation [

30]. Additionally, in accordance with our findings, a previous study involving pharmacological activation (with Yoda1) or inhibition (via GsMTx-4) of Piezo1 in the MK/platelet lineage reported a stimulating or inhibiting, respectively, effect on platelet activation by collagen and thrombin [

31]. These results collectively suggest a pivotal role of platelet Piezo1 in controlling thrombosis, thus validating Piezo1 as a potential drug target.

A relationship between mechanosensitive ion channels and inflammation has been found to be bidirectional, where localized inflammation and mechanical forces (shear stress and tissue stretching) have been reported to activate various ion channels [

32]; this activation triggers a series of intracellular events, leading to modulation of expression of inflammatory cytokines through complex signaling cascades [

32]. In our study, WBC count was significantly reduced upon Piezo1 deletion in PF4-Cre-mediated Piezo1 KO mice, leading us to evaluate the impact of this state on inflammatory cytokine levels. Detecting a reduced WBC count was not surprising, considering that PF4-Cre targets hematopoietic progenitors, including MPP3 and MPP4 [

23]. It is then possible that the lack of Piezo1 affected the number of progenitors differentiating into WBCs, resulting in their reduced level in the circulation. It seems, however, that once MPP4 diverged to fully differentiated WBCs, PF4-Cre was no longer active, as we did not detect a significant reduction in Piezo1 expression in WBCs derived from Piezo1 KO mice. Recent reports are also confirmatory of Piezo1 expression in WBCs, which in turn plays key roles in inflammation [

32,

33].

Moreover, no significant difference in the levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-6 was found between PF4-Cre and Piezo1 KO mice sera at baseline. Surprisingly, LPS-mediated systemic inflammation resulted in reduced levels of IL-6 and IFN-γ in Piezo1 KO mice compared to matching controls (PF4-Cre); this, in turn, is indicative of putative roles of Piezo1 in inflammation, in accordance with other reports [

34,

35]. Reduced WBC count in the KO mice and/or the deletion of MK Piezo1 could account for the observed reduction in IL-6 or TNF-alpha upon LPS challenge. Indeed, IL-6 is a key cytokine release by WBCs, which in turn influences WBC’s inflammatory behavior [

36,

37] and the production of inflammatory cytokines [

38]. Additionally, IL-6 KO mice have reduced WBC count in response to inflammatory stress [

37,

38]. As to the contribution of Piezo1 KO MKs to this phenotype, we found that only IL-6 was significantly reduced in these cells when cultured under unstimulated (no LPS) conditions; however, this reduction seems not to have contributed to changes in the mouse plasma level of this cytokine at baseline.