Macrophage-Derived Exosomal MALAT1 Induced by Hyperglycemia Regulates Vascular Calcification Through miR-143-3p/MGP Axis in Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Diabetic Rat Carotid Artery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Hyperglycemic Stress Environment

2.3. Extraction of Exosomes from Cell Media

2.4. RNA Quality Assessment of Exosomes

2.5. Reverse Transcription and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.6. Partial Mouse (A) MALAT1 DNA Fragment (B) MGP DNA Fragment (Contains mir-143-3p Binding Site) Construction

- (A)

- A 500 bp mouse MALAT1 DNA fragment (Malat1-201 ENSMUST00000172812.4 _3385~3884 bp; Chromosome 19: 5,845,717-5,852,704; http://www.ensembl.org/index.html, (accessed on 18 October 2025)) was generated by artificial synthesis and clone was digested with SacI and Xbal restriction enzymes and ligated into pmirNanoGLO plasmid vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The cloned mouse MALAT1 DNA fragment contains miR-143-3p potential binding site (from 3614 bp to 3634 bp). For the mutant, the conserved sites, GAAGATCAAATGTTCATCTCA, were mutated into ACAGATACAATGGGACGAGAC and were constructed by the same method described above. All the cloned plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Seeing Bioscience Co., Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan).

- (B)

- A 209 bp mouse MGP DNA fragment (Mgp-201 ENSMUST00000032342.3 _1~209 bp; Chromosome 6: 136,849,433-136,852,821; http://www.ensembl.org/index.html, (accessed on 18 October 2025)) was generated by artificial synthesis and clone was digested with SacI and Xbal restriction enzymes and ligated into pmirNanoGLO plasmid vector (Promega). The cloned mouse MGP DNA fragment contains miR-143-3p potential binding site (from 26 bp to 46 bp).For the mutant, the conserved sites, GGAGTTTCGTTTTATATCTCC, were mutated into TGAGGTTCTGTTGATCGAGAC and were constructed by the same method described above. All the cloned plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Seeing Bioscience Co., Ltd.).

2.7. Luciferase Activity Assay

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

2.9. Calcium Colorimetric Assay

2.10. Balloon Injury of the Carotid Artery in Diabetic Rats and Delivery of Exosomes Containing Macrophage-Derived MALAT1

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

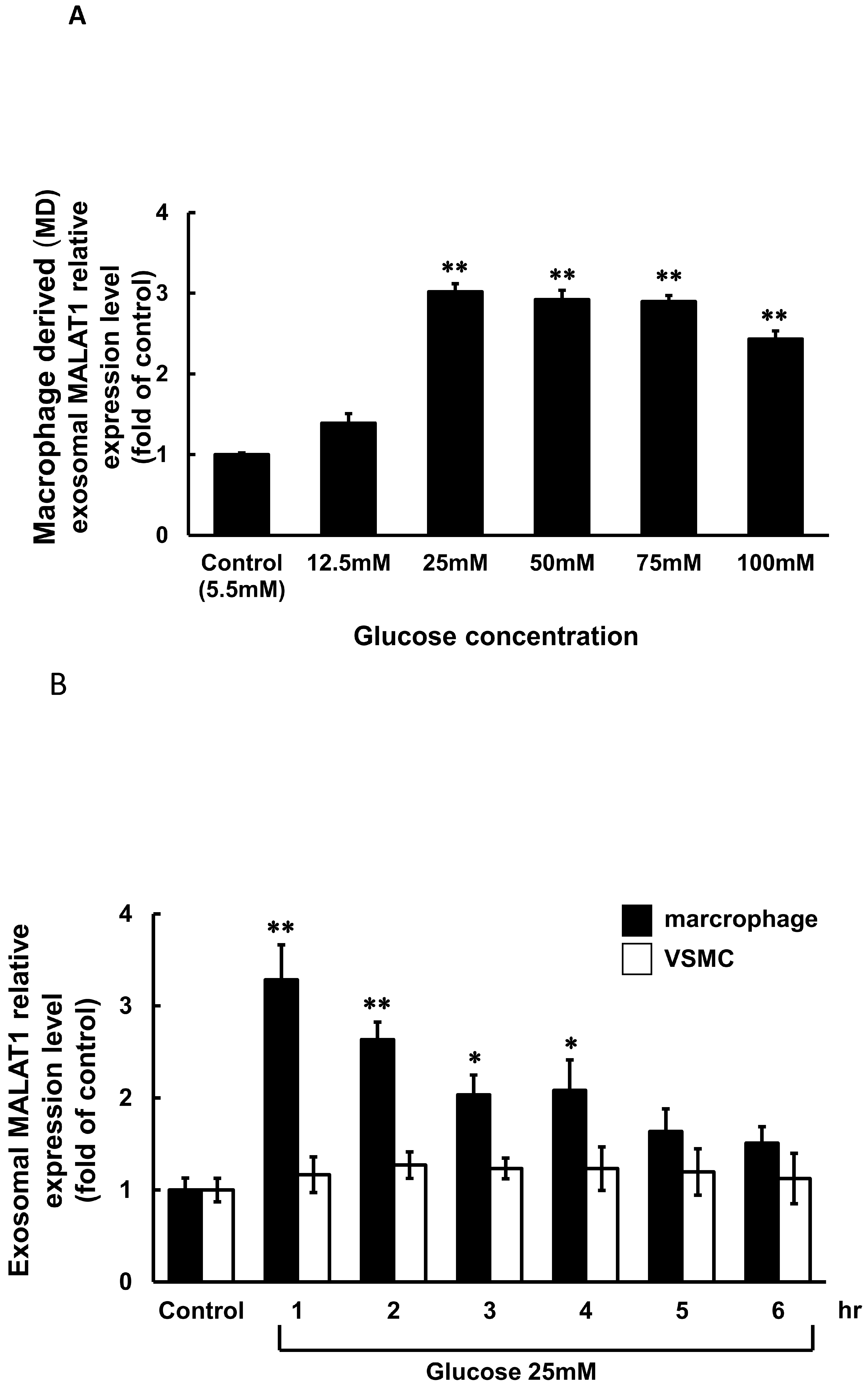

3.1. High Glucose Induced Exosomal MALAT1 Expression in Cultured Macrophages

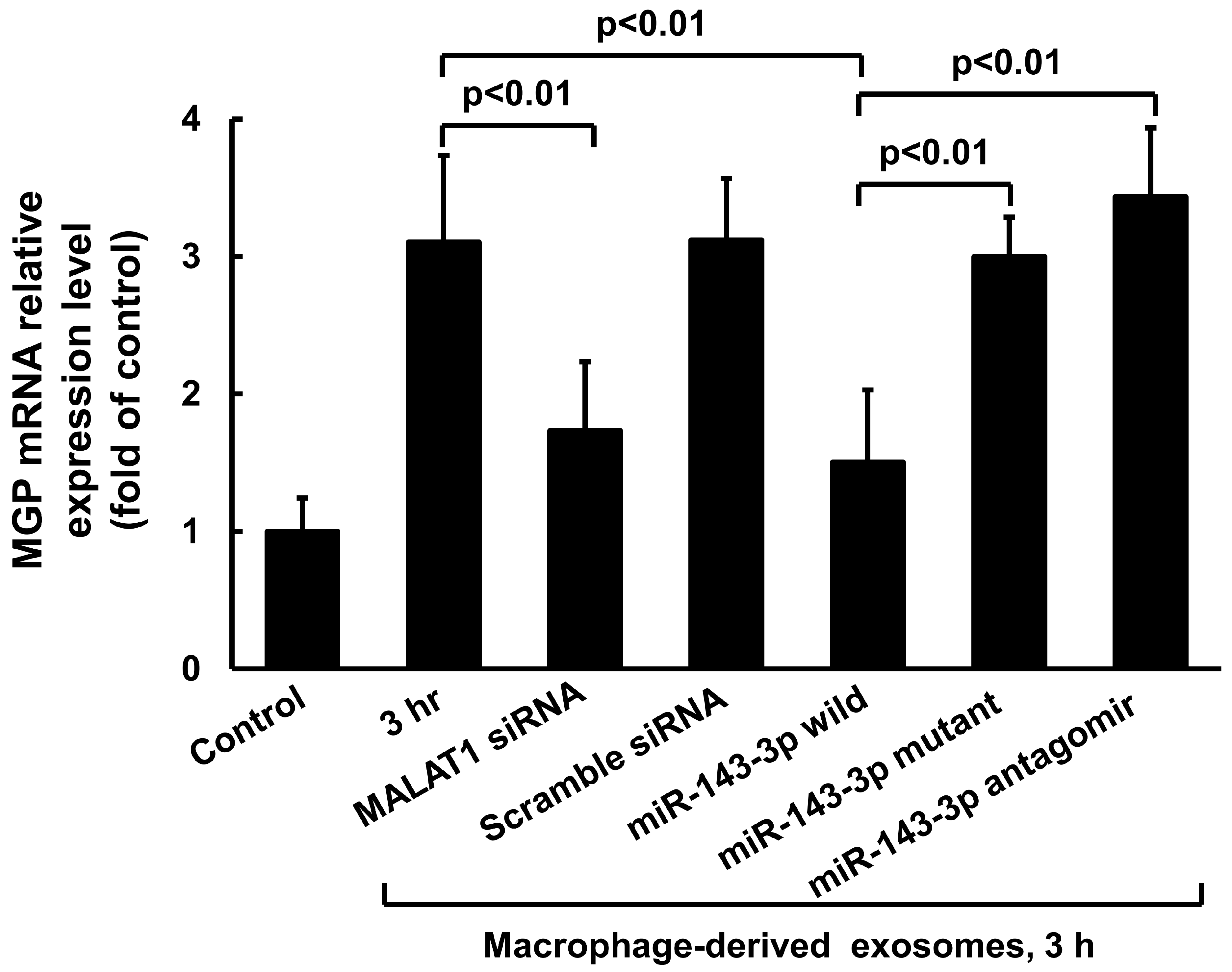

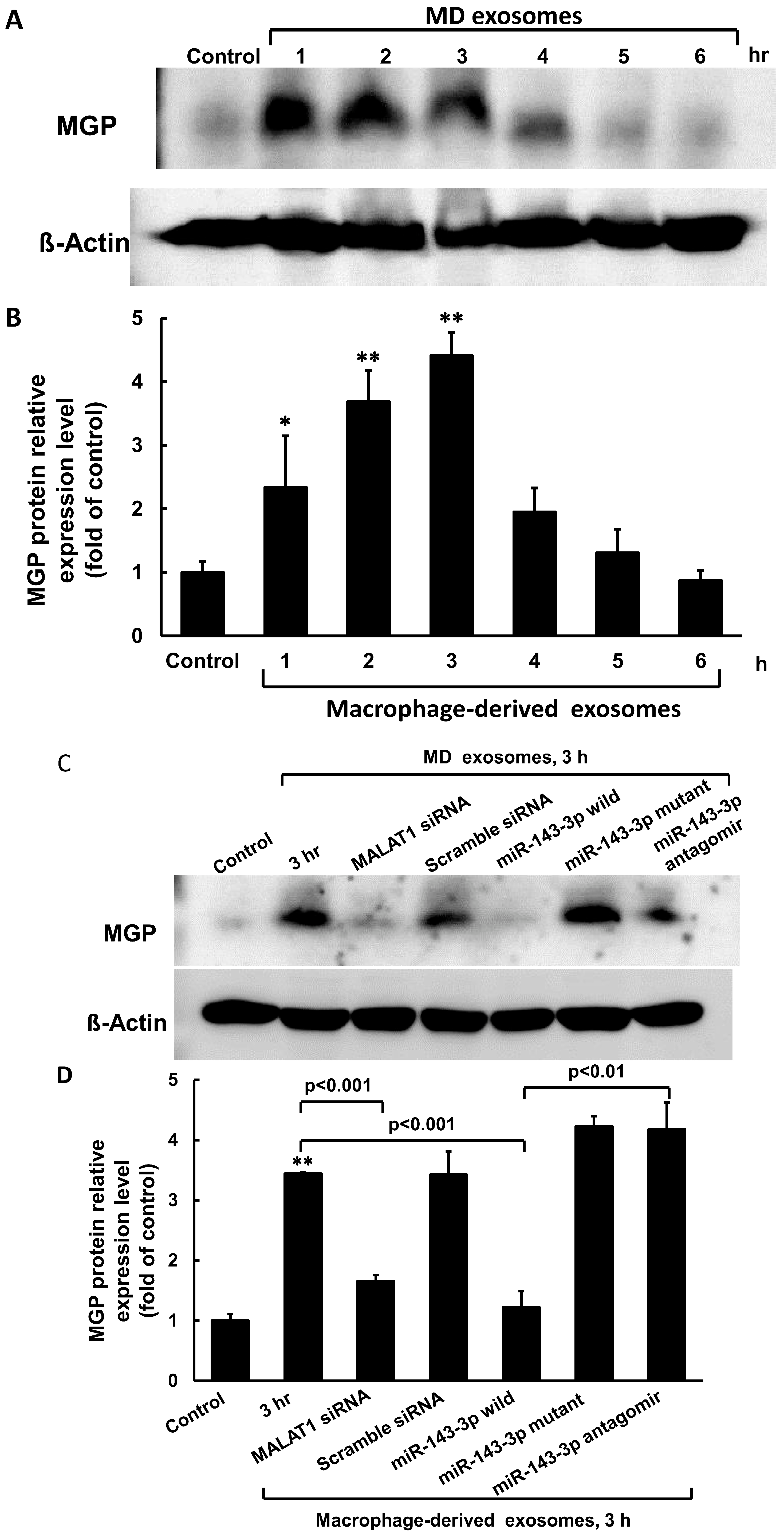

3.2. Macrophage-Derived Exosomes Decreased miR-143-3p and Increased MGP Expression in Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells

3.3. MiR-143-3p Decreased MALAT1 and MGP Luciferase Activity in Cultured VSMC Treated with Macrophage-Derived Exosomes

3.4. MiR-143-3p Increased Calcium Content in Cultured VSMC Treated with Macrophage-Derived Exosomes

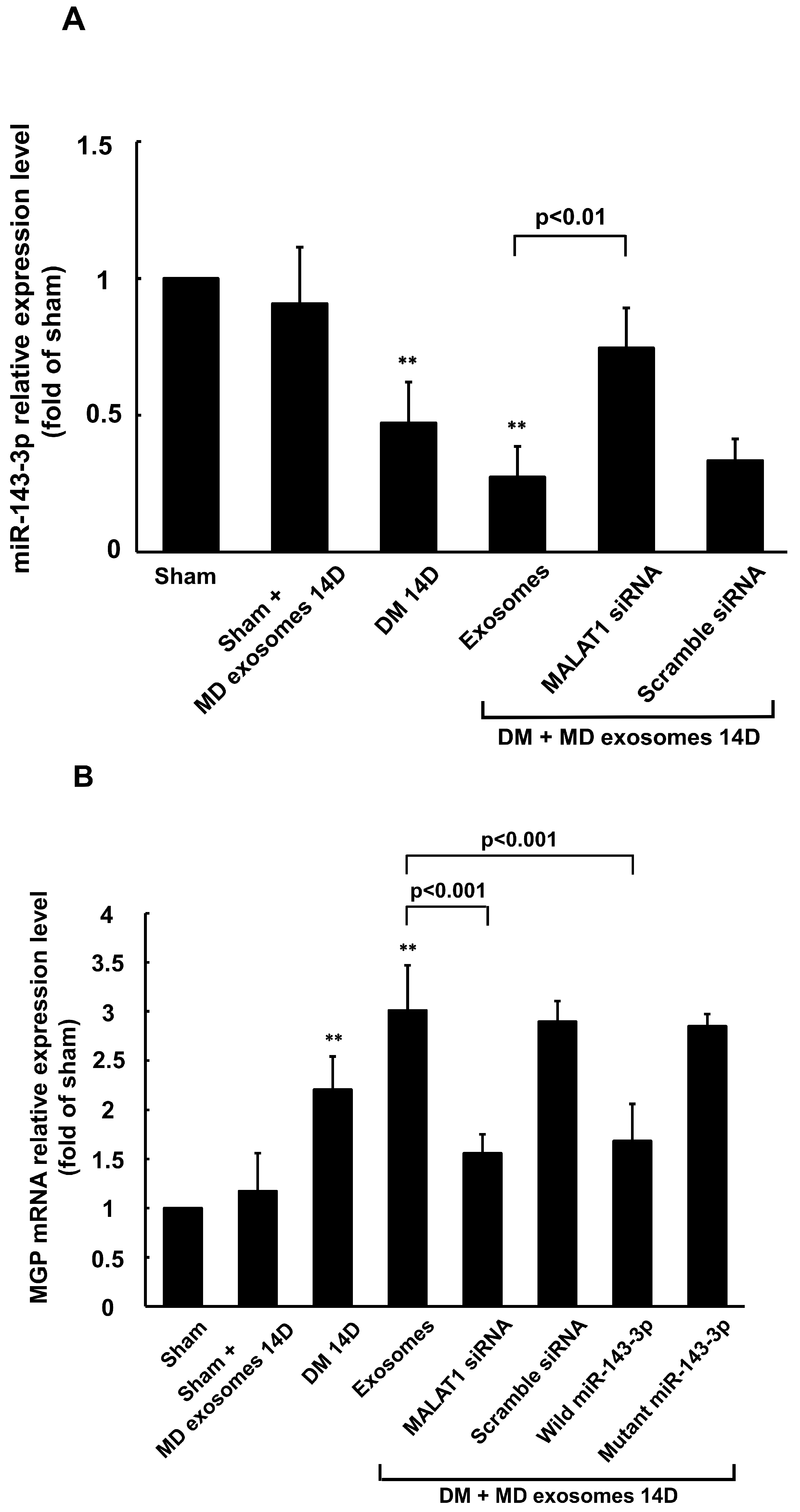

3.5. Carotid Artery Balloon Injury Enhances MALAT1 Expression to Inhibit miR204-5p Expression in Diabetic Rats

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gui, Z.; Shao, C.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. Vascular calcification: High incidence sites, distribution, and detection. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2024, 72, 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, K.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Lutter, C.; Mori, H.; Romero, M.E.; Finn, A.V.; Virmani, R. Pathology of human coronary and carotid artery atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Roco, A.; Lago, B.M.; Villa-Bellosta, R. Elevated glucose levels increase vascular calcification risk by disruption extracellular pyrophosphate metabolism. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Chao, T.H.; Lin, T.H.; Cheng, C.I.; Wu, Y.W.; Ueng, K.C.; Wu, Y.J.; Lin, W.W.; Leu, H.B.; Cheng, H.M.; Huang, C.C.; et al. 2024 Guidelines of the Taiwan Society of Cardiology on the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease—Part I. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 2024, 40, 479–543. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R.; Ji, Z.; Wang, M.; Ma, G. Role of macrophages in vascular calcification: From the perspective of homeostasis. Int. Immunol. 2025, 144, 113635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Shao, C.; Jing, L.; Li, L.; Wang, Z. Role of macrophages in the progression and regression of vascular calcification. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, L.; Moccetti, T.; Marban, E.; Vassalli, G. Roles of exosomes in cardioprotection. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, R.C.C.; Hirata, R.D.C.; Hirata, M.H.; Aikawa, E. Circulating extracellular vesicles as biomarkers and drug delivery vehicles in cardiovascular diseases. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Huang, F.; Feng, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Luo, P.; Huang, H. Exosomes, the message transporters in vascular calcification. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 4024–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Ni, Y.; Li, C.; Xiang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, J.; et al. Long noncoding RNA SNHG1 alleviates high glucose-induced vascular smooth muscle cells calcification/senescence by post-transcriptionally regulating Bhlhe40 and autophagy via Atg10. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 79, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Qi, H.; Yao, L. A long non-coding RNA H19/microRNA-138/TLR3 network is involved in high phosphorus-mediated vascular calcification and chronic kidney disease. Cell Cycle 2022, 21, 1667–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Xia, Y.; Wen, Y.; Gan, H. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 sponges miR-30c to promote the calcification of human vascular smooth muscle cells by regulating Runx2. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2204953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Ahn, Y.; Kook, H.; Kim, Y.K. The roles of non-coding RNAs in vascular calcification and opportunities as therapeutic targets. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 218, 107675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yao, H.; Wang, K.; Liu, X. Long- non-coding RNA MALAT1 regulates ZEB1 expression by sponging miR-143-3p and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. J. Cell Biochem. 2017, 118, 4836–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolatabadi, N.F.; Dehghani, A.; Shahand, E.; Yazdanshenas, M.; Tabatabaeian, H.; Zamani, A.; Azadeh, M.; Ghaedi, K. The interaction between MALAT1 target, miR143-3p, and RALGAPA2 is affected by functional SNP re3827693 in breast cancer. Hum. Cell 2020, 33, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettsch, C.; Hutcheson, J.D.; Aikawa, E. MicroRNA in cardiovascular calcification: Focus on targets and extracellular vesicle vesicle delivery mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, J.; Park, D.H.; Hobuß, L.; Anaraki, P.K.; Pfanne, A.; Just, A.; Mitzka, S.; Dumler, I.; Weidemann, F.; Hilfiker, A.; et al. Identification of miR-143 as a major contributor for human stenotic aortic valve disease. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2019, 12, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, H.; O’Keeffe, M.; Kavanagh, E.; Walsh, M.; O’Connor, E.M. Is matrix Gla protein associated with vascular calcification? A systemic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, K.G.; Wang, B.W.; Pan, C.M.; Fang, W.J. Macrophage-derived exosomal MALAT1 regulates autophagy through miR-204-5p/ATG7 axis in H9C2 cardiomyocytes and diabetic rat heart. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 2025, 41, 346–360. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.M.; Hou, S.W.; Wang, B.W.; Ong, J.R.; Chang, H.; Shyu, K.G. Molecular mechanism of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate on balloon injury-induced neointimal formation and leptin expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, I.; Motohashi, H.; Dallenga, T.; Schaible, U.E.; Benhar, M. Redox signaling in innate immunity and inflammation: Focus on macrophages and neutrophils. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 237, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Zhen, W.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y. IncRNA MALAT1/miR-143 axis is a potential biomarker for in-stent restenosis and is involbed in the multiplication of vascular smooth muscle cells. Open Life Sci. 2021, 16, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shyu, K.-G.; Wang, B.-W.; Fang, W.-J.; Pan, C.-M. Macrophage-Derived Exosomal MALAT1 Induced by Hyperglycemia Regulates Vascular Calcification Through miR-143-3p/MGP Axis in Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Diabetic Rat Carotid Artery. Cells 2025, 14, 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241995

Shyu K-G, Wang B-W, Fang W-J, Pan C-M. Macrophage-Derived Exosomal MALAT1 Induced by Hyperglycemia Regulates Vascular Calcification Through miR-143-3p/MGP Axis in Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Diabetic Rat Carotid Artery. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241995

Chicago/Turabian StyleShyu, Kou-Gi, Bao-Wei Wang, Wei-Jen Fang, and Chun-Ming Pan. 2025. "Macrophage-Derived Exosomal MALAT1 Induced by Hyperglycemia Regulates Vascular Calcification Through miR-143-3p/MGP Axis in Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Diabetic Rat Carotid Artery" Cells 14, no. 24: 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241995

APA StyleShyu, K.-G., Wang, B.-W., Fang, W.-J., & Pan, C.-M. (2025). Macrophage-Derived Exosomal MALAT1 Induced by Hyperglycemia Regulates Vascular Calcification Through miR-143-3p/MGP Axis in Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Diabetic Rat Carotid Artery. Cells, 14(24), 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241995