Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Variants Interact with Amyloid-Beta to Modulate Monocyte Function

Highlights

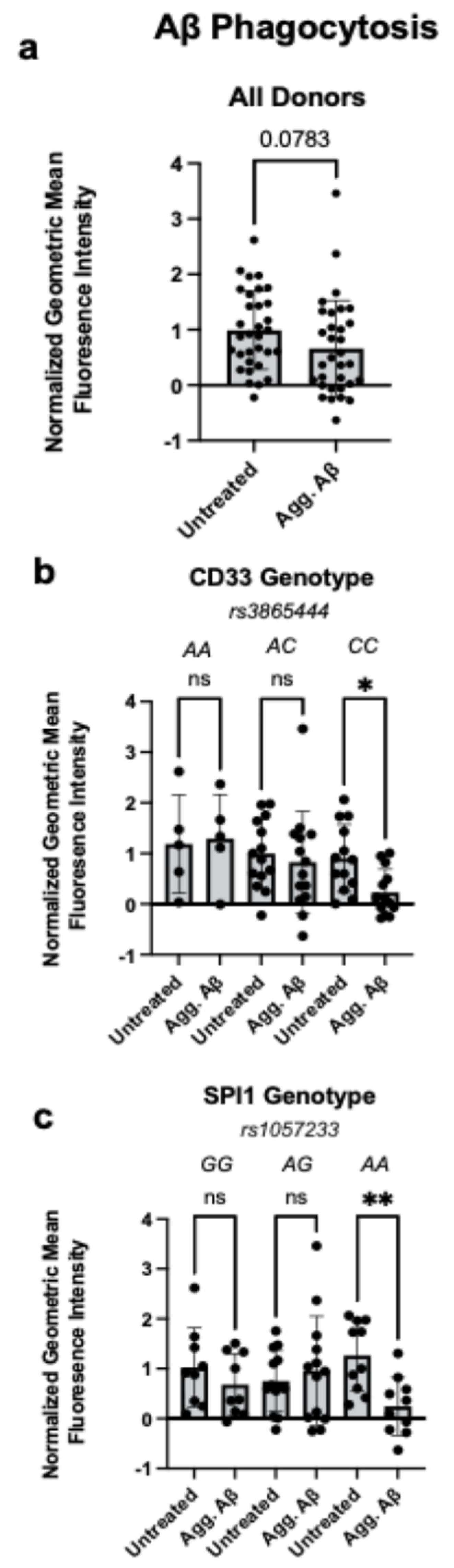

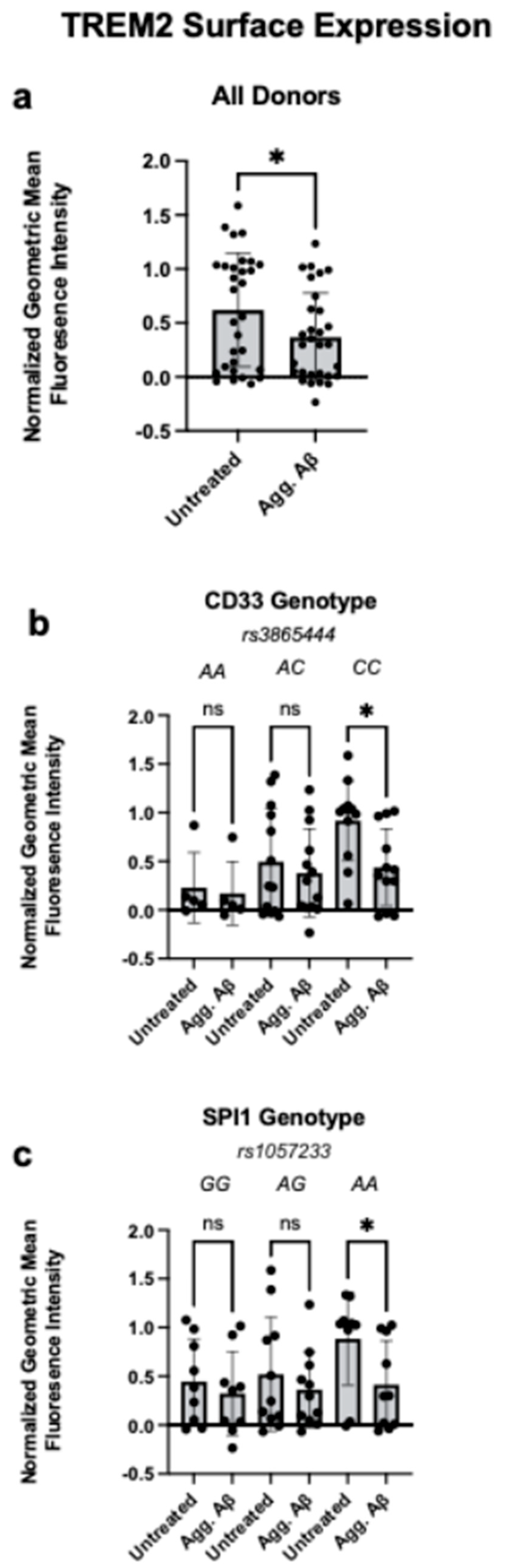

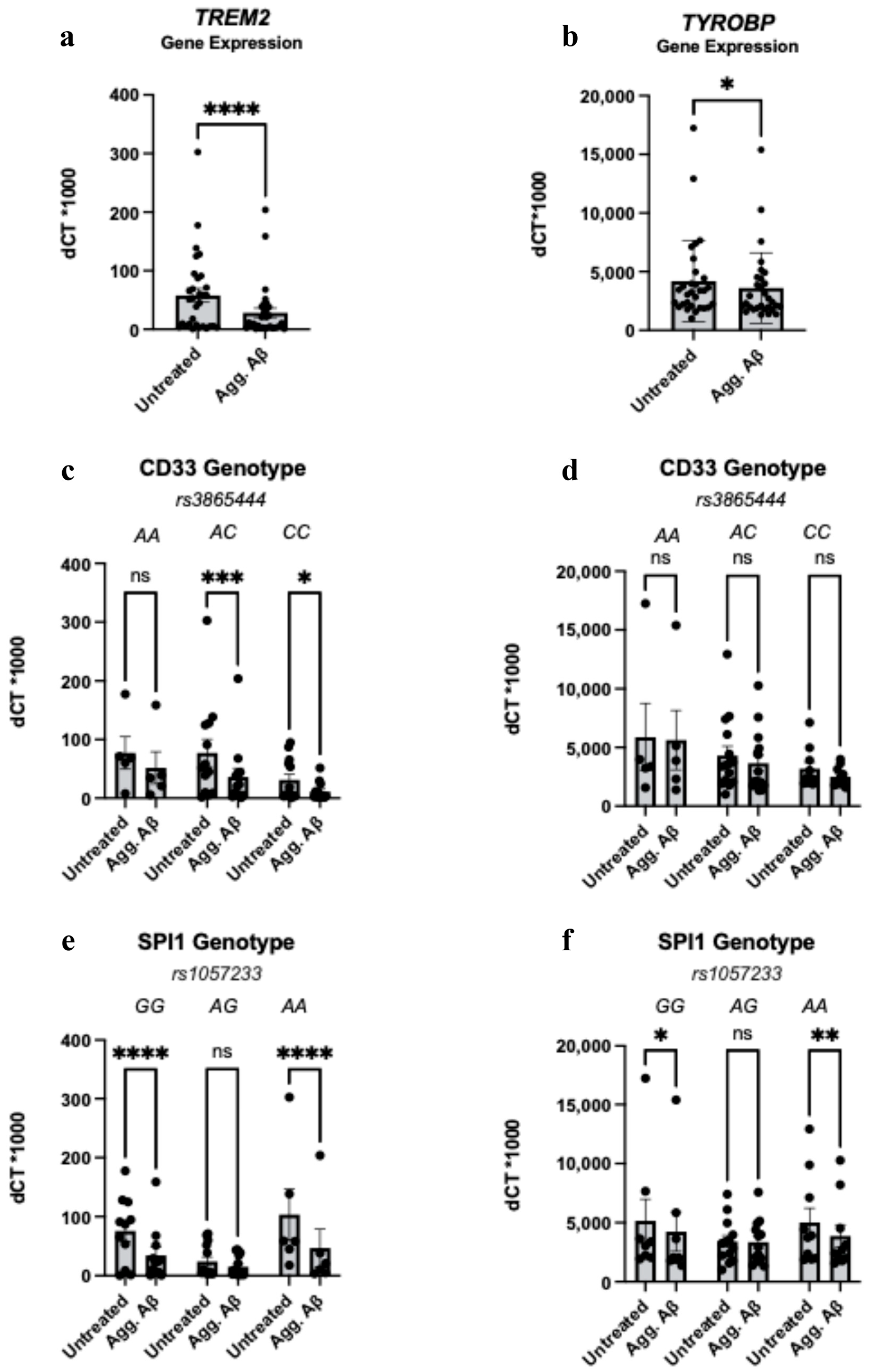

- Aggregated Aβ reduces phagocytosis and decreases surface TREM2 expression in monocytes carrying CD33 rs3865444 or SPI1 rs1057233 AD-genetic risk variants.

- Genetic variants interact with Aβ to reduce myeloid cell fitness in the periphery.

- These findings highlight that peripheral monocytes, like brain-resident microglia, are genetically and functionally linked to AD risk.

- These results emphasize the importance of studying peripheral myeloid cells to understand genetically influenced immune dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Human Blood Samples

2.2. Genotyping

2.3. Collection of Human Peripheral PBMCs and Monocyte Isolation

2.4. Amyloid Aggregation

2.5. Amyloid Phagocytosis Assay

2.6. TREM2 Surface Staining

2.7. RNA Expression of TREM2 and TYROBP

2.8. Batch Correction

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Aggregated Aβ1-42 Impairs Phagocytosis in Monocytes Carrying CD33 and SPI1 AD Risk Variants

3.2. Aggregated Aβ1-42 Reduces Monocyte TREM2 Surface Expression in CD33 and SPI1 Risk Variants

3.3. Aggregated Aβ1-42 Influences TREM2 and TYROBP Transcription in a Genotype-Independent Manner

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatila, Z.K.; Bradshaw, E.M. Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics: A Dampened Microglial Response? Neuroscientist 2023, 29, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, G.; Kapoor, M.; Tcw, J.; Abud, E.M.; Efthymiou, A.G.; Chen, S.X.; Cheng, H.; Fullard, J.F.; Bendl, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Integration of Alzheimer’s disease genetics and myeloid genomics identifies disease risk regulatory elements and genes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, J.P.; Bellavance, M.A.; Préfontaine, P.; Rivest, S. Real-time in vivo imaging reveals the ability of monocytes to clear vascular amyloid beta. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.A.; Kulstad, J.J.; Savard, C.E.; Green, P.S.; Lee, S.P.; Craft, S.; Watson, G.S.; Cook, D.G. Peripheral amyloid-beta levels regulate amyloid-beta clearance from the central nervous system. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009, 16, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellanas, M.A.; Purnapatre, M.; Burgaletto, C.; Schwartz, M. Monocyte-derived macrophages act as reinforcements when microglia fall short in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritzel, R.; Patel, A.R.; Grenier, J.M.; Crapser, J.; Verma, R.; Jellison, E.R.; McCullough, L.D. Functional differences between microglia and monocytes after ischemic stroke. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, E.M.; Chibnik, L.B.; Keenan, B.T.; Ottoboni, L.; Raj, T.; Tang, A.; Rosenkrantz, L.L.; Imboywa, S.; Lee, M.; Korff, A.V.; et al. CD33 Alzheimer’s disease locus: Altered monocyte function and amyloid biology. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 848–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, G.; White, C.C.; A Winn, P.; Cimpean, M.; Replogle, J.M.; Glick, L.R.; E Cuerdon, N.; Ryan, K.J.; A Johnson, K.; A Schneider, J.; et al. CD33 modulates TREM2: Convergence of Alzheimer loci. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1556–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, R.; Wojtas, A.; Bras, J.; Carrasquillo, M.; Rogaeva, E.; Majounie, E.; Cruchaga, C.; Sassi, C.; Kauwe, J.S.; Younkin, S.; et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griciuc, A.; Patel, S.; Federico, A.N.; Choi, S.H.; Innes, B.J.; Oram, M.K.; Cereghetti, G.; McGinty, D.; Anselmo, A.; Sadreyev, R.I.; et al. TREM2 Acts Downstream of CD33 in Modulating Microglial Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 103, 820–835.e827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.L.; Initiative, T.A.D.N.; Marcora, E.; A Pimenova, A.; Di Narzo, A.F.; Kapoor, M.; Jin, S.C.; Harari, O.; Bertelsen, S.; Fairfax, B.P.; et al. A common haplotype lowers PU.1 expression in myeloid cells and delays onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustenhoven, J.; Smith, A.M.; Smyth, L.C.; Jansson, D.; Scotter, E.L.; Swanson, M.E.V.; Aalderink, M.; Coppieters, N.; Narayan, P.; Handley, R.; et al. PU.1 regulates Alzheimer’s disease-associated genes in primary human microglia. Molecular. Neurodegener. 2018, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodger, M.P.; Hart, D.N. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the CD33 promoter. Br. J. Haematol. 1998, 102, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenova, A.A.; Herbinet, M.; Gupta, I.; Machlovi, S.I.; Bowles, K.R.; Marcora, E.; Goate, A.M. Alzheimer’s-associated PU.1 expression levels regulate microglial inflammatory response. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 148, 105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lengerich, B.; Zhan, L.; Xia, D.; Chan, D.; Joy, D.; Park, J.I.; Tatarakis, D.; Calvert, M.; Hummel, S.; Lianoglou, S.; et al. A TREM2-activating antibody with a blood-brain barrier transport vehicle enhances microglial metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease models. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinberger, G.; Yamanishi, Y.; Suárez-Calvet, M.; Czirr, E.; Lohmann, E.; Cuyvers, E.; Struyfs, H.; Pettkus, N.; Wenninger-Weinzierl, A.; Mazaheri, F.; et al. TREM2 mutations implicated in neurodegeneration impair cell surface transport and phagocytosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 243ra286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M. TREMs in the immune system and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M. The biology of TREM receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Ornatowska, M.; Joo, M.S.; Sadikot, R.T. TREM-1 expression in macrophages is regulated at transcriptional level by NF-kappaB and PU.1. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007, 37, 2300–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovde, M.J.; Maaser-Hecker, A.; Bae, J.S.; Tanzi, R.E. Inhibition of Acyl-CoenzymeA: Cholesterol Acyltransferase 1 promotes shedding of soluble triggering receptor on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) and low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LRP1)-dependent phagocytosis of amyloid beta protein in microglia. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.C.; George-Hyslop, P.S. Does Soluble TREM2 Protect Against Alzheimer’s Disease? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 834697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sudan, R.; Peng, V.; Zhou, Y.; Du, S.; Yuede, C.M.; Lei, T.; Hou, J.; Cai, Z.; Cella, M.; et al. TREM2 drives microglia response to amyloid-β via SYK-dependent and -independent pathways. Cell 2022, 185, 4153–4169.e4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piehl, N.; van Olst, L.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Teregulova, V.; Simonton, B.; Zhang, Z.; Tapp, E.; Channappa, D.; Oh, H.; Losada, P.M.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid immune dysregulation during healthy brain aging and cognitive impairment. Cell 2022, 185, 5028–5039.e5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiala, M.; Lin, J.; Ringman, J.; Kermani-Arab, V.; Tsao, G.; Patel, A.; Lossinsky, A.S.; Graves, M.C.; Gustavson, A.; Sayre, J.; et al. Ineffective phagocytosis of amyloid-β by macrophages of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2005, 7, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thériault, P.; ElAli, A.; Rivest, S. The dynamics of monocytes and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2015, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, M.; Priller, J. Tickets to the brain: Role of CCR2 and CX3CR1 in myeloid cell entry in the CNS. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 224, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlepckow, K.; Monroe, K.M.; Kleinberger, G.; Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Parhizkar, S.; Xia, D.; Willem, M.; Werner, G.; Pettkus, N.; Brunner, B.; et al. Enhancing protective microglial activities with a dual function TREM2 antibody to the stalk region. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e11227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Black, S.E.; Frosch, M.P.; Greenberg, S.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Scheltens, P.; Carrillo, M.C.; Thies, W.; Bednar, M.M.; et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: Recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salloway, S.; Chalkias, S.; Barkhof, F.; Burkett, P.; Barakos, J.; Purcell, D.; Suhy, J.; Forrestal, F.; Tian, Y.; Umans, K.; et al. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in 2 Phase 3 Studies Evaluating Aducanumab in Patients with Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatila, Z.K.; Bradshaw, E.M. Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Variants Interact with Amyloid-Beta to Modulate Monocyte Function. Cells 2025, 14, 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241990

Chatila ZK, Bradshaw EM. Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Variants Interact with Amyloid-Beta to Modulate Monocyte Function. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241990

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatila, Zena K., and Elizabeth M. Bradshaw. 2025. "Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Variants Interact with Amyloid-Beta to Modulate Monocyte Function" Cells 14, no. 24: 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241990

APA StyleChatila, Z. K., & Bradshaw, E. M. (2025). Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Variants Interact with Amyloid-Beta to Modulate Monocyte Function. Cells, 14(24), 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241990