Maintenance and Decline of Neuronal Lysosomal Function in Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Lysosomal Functions in Neurons

2.1. Catabolism and Recycling

2.2. Signaling and Regulatory Roles

2.3. Transport and Spatial Organization

3. Neuronal Lysosomes in Aging

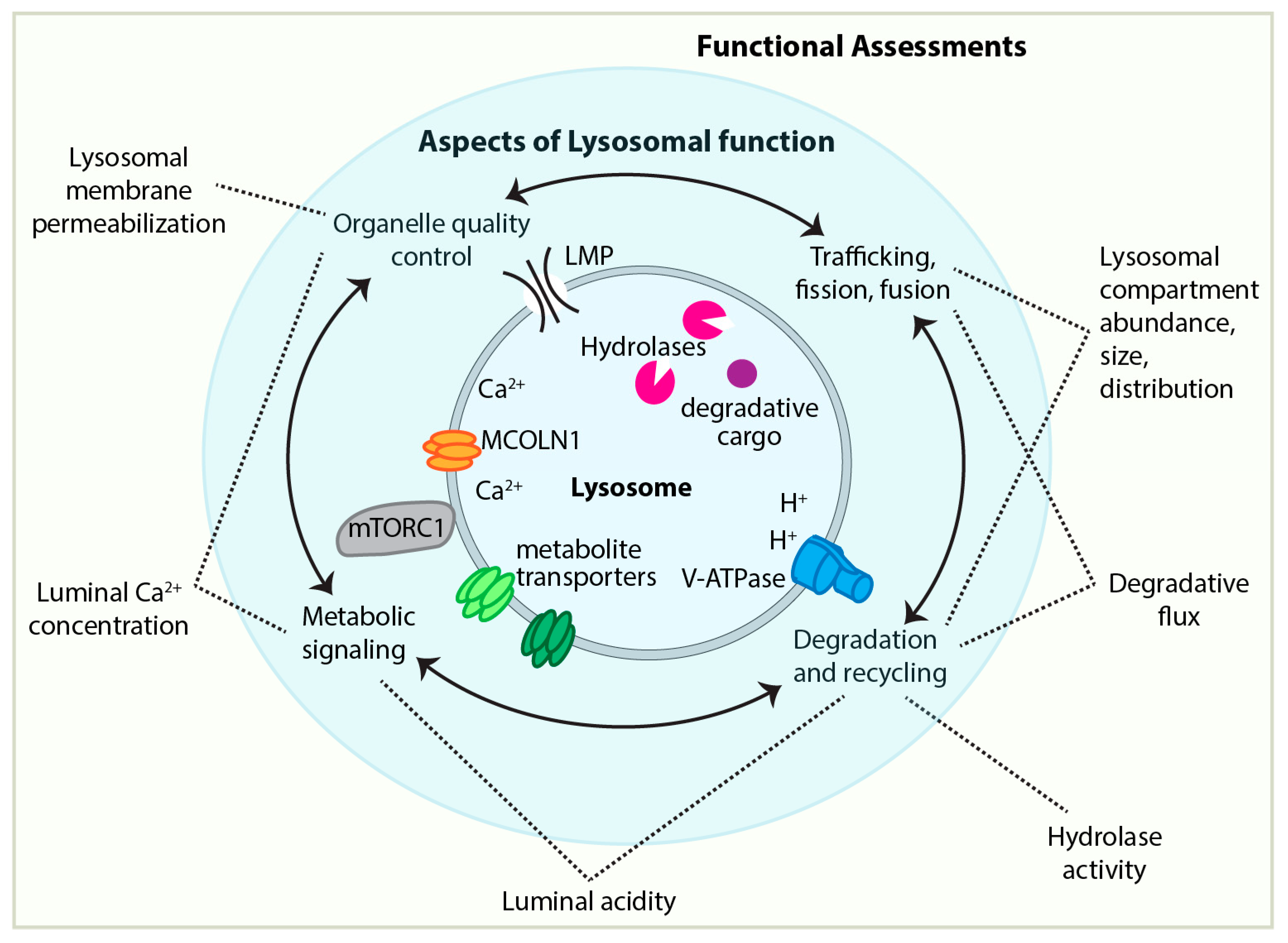

3.1. Approaches to and Challenges of Assessing Lysosomal Functionality

3.2. Neuronal Lysosomal Dysfunction in Aging: Overview of the Evidence

3.2.1. Hints and Correlations

3.2.2. Evidence of Neuronal Lysosomal Dysfunction in Aging

3.2.3. Functional Consequences of Neuronal Lysosomal Dysfunction

3.2.4. Autophagic Dysfunction, Upstream of Lysosomal Function, with Age

4. Regulation of Lysosomal Functional Capacity: TFEB and Quality Control

4.1. TFEB-Mediated Lysosomal Biogenesis

4.2. Lysosomal Quality Control

- (1)

- (2)

- Sense and repair damage: LMP, Ca2+ efflux, and/or disrupted lysosomal acidity can activate several partially overlapping repair pathways. Ca2+ efflux from the lysosomal lumen is both a hazard and a signal: elevation of local cytosolic Ca2+ rapidly recruits ESCRT machinery to the lysosomal membrane, which promotes repair [266,267,268,269]. Annexin A7 promotes lysosome repair in parallel to ESCRT-III [270]. The mechanisms of both ESCRT- and Annexin A7-mediated repair are not fully understood, but both are thought to involve inducing negative membrane curvature from the cytosolic face of the lysosomal membrane [266,267,268,269,270]. Stress granules form at sites of LMP, stabilizing the membrane and facilitating repair through both ESCRT-dependent and independent mechanisms [271]. LMP can also be repaired by the phosphoinositide-initiated tethering and lipid transport (PITT) pathway, which involves transfer of phosphatidylserine and cholesterol from the ER to the lysosomal membrane [272,273]. Another way in which the ER participates in repairing damaged lysosomes uses the ER-resident, lipid-transport protein VPS13C; the cytosolic side of VPS13C associates with damaged lysosomal membrane, likely to facilitate the transport of lipids from the ER to the lysosome [274].The conjugation of ATG8 to single membranes (CASM) pathway provides another major repair mechanism. CASM is activated by lysosomal deacidification or ionic imbalance to repair the lysosome [25,275]. Activation of CASM at lysosomal compartments can occur through two parallel mechanisms: one involves flipping sphingomyelin from the lysosome luminal to cytosolic side [276], and the other involves V-ATPase recruitment of ATG16L1 to the lysosome [25,277].

- (3)

- Stress-responsive expansion of lysosomal capacity: Efflux of Ca2+ from the lysosomal lumen can activate calcineurin, which dephosphorylates TFEB to promote transcriptional expansion of lysosomal and autophagic capacity [85]. The CASM machinery also facilitates activation of TFEB/TFE3 during lysosomal stress [278].

- (4)

- Removal of damaged lysosomes: When repair mechanisms are insufficient, damaged lysosomes can be selectively eliminated by lysophagy—selective autophagy of the lysosome [266]. To initiate lysophagy, LMP is sensed by cytosolic galectins, which bind lysosomal luminal beta-galactosides that become exposed by the membrane rupture [279,280,281,282]. Some of these galectins induce ubiquitination of the lysosome, triggering lysophagy through a mechanism that involves recruitment of VCP/p97 [108,280,282,283]. Pathogenic mutations in VCP/p97 cause disorders including frontotemporal dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Parkinsonism; in addition to promoting lysophagy, VCP/p97 is also an effector of macroautophagy, and both of these functions likely contribute to neuron pathologies [284,285]. Damaged lysosomes can also be removed from the cell via lysosomal exocytosis [286].

5. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| ILV | Intraluminal vesicle |

| RAB5 | Ras-related protein in brain 5 |

| RAB7 | Ras-related protein in brain 7 |

| VAMP7 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 |

| BORC | BLOC-1-Related Complex |

| HOPS | Homotypic fusion and protein sorting |

| LYST | Lysosomal trafficking regulator |

| TFEB | Transcription factor EB |

| TFE3 | Transcription factor E3 |

| CMA | Chaperone-mediated autophagy |

| BEACH | Beige and Chediak-Higashi domain |

| LSD | Lysosomal storage disorder |

| MCOLN1 | Mucolipin-1 |

| TRPML1 | Transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 |

| IP3 | Inositol Trisphosphate |

| IP3R | Inositol triphosphate receptor |

| RYR | Ryanodine receptor |

| MVB | Multivesicular body |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| CLEM | Correlated light and electron microscopy |

| SBEM | Serial block-face electron microscopy |

| FIB-SEM | Focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy |

| LAMP1 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| ARGO | Analysis of red-green offset |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| GCaMP | Genetically encoded calcium indicator |

| LMP | Lysosomal membrane permeabilization |

| NMJ | Neuromuscular junction |

| CA | Cornu ammonis |

| PFC | Prefrontal cortex |

| LAMP2A | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2A |

| ROS | Reactive oxidative species |

| EC-SOD | Extracellular superoxide dismutase |

| AGE | Advanced glycation end-products |

| DIV | Days in vitro |

| LLOME | L-leucyl-L-leucine O-methyl ester |

| SNT | Synaptotagmin |

| SNG | Synaptogyrin |

| Aβ | Beta-amyloid |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| NPC | Niemann–Pick type C |

| POMC | Proopiomelanocortin |

| ATG8 | Autophagy-related protein 8 |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERK2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 |

| PP2A | Protein phosphatase 2A |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| MYC | Myelocytomatosis oncogene |

| CARM1 | Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 |

| BNIP3 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3 |

| ESCRT | Endosomal sorting complexes required for transport |

| PITT | Phosphoinositide-initiated tethering and lipid transport |

| CASM | Conjugation of ATG8 to single membranes |

References

- Yang, C.; Wang, X. Lysosome Biogenesis: Regulation and Functions. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballabio, A.; Bonifacino, J.S. Lysosomes as Dynamic Regulators of Cell and Organismal Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.E.; Zoncu, R. The Lysosome as a Cellular Centre for Signalling, Metabolism and Quality Control. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, D.W.; Bar-Peled, L. Lysosome: The Metabolic Signaling Hub. Traffic 2019, 20, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre, C.; Perera, R.M. Lysosomes as Coordinators of Cellular Catabolism, Metabolic Signalling and Organ Physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, D.C.; Staiano, L.; Guimas Almeida, C.; Cutler, D.F.; Eden, E.R.; Futter, C.E.; Galione, A.; Marques, A.R.A.; Medina, D.L.; Napolitano, G.; et al. Current Methods to Analyze Lysosome Morphology, Positioning, Motility and Function. Traffic 2022, 23, 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roney, J.C.; Cheng, X.T.; Sheng, Z.H. Neuronal Endolysosomal Transport and Lysosomal Functionality in Maintaining Axonostasis. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 221, e202111077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C.; Hugelier, S.; Xing, J.; Sorokina, E.M.; Lakadamyali, M. Heterogeneity of Late Endosome/Lysosomes Shown by Multiplexed DNA-PAINT Imaging. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 224, e202403116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winckler, B.; Faundez, V.; Maday, S.; Cai, Q.; Guimas Almeida, C.; Zhang, H. The Endolysosomal System and Proteostasis: From Development to Degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 9364–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, P.P.Y.; Yang, D.S.; Stavrides, P.; Goulbourne, C.N.; Zheng, P.; Mohan, P.S.; Cataldo, A.M.; Nixon, R.A. Post-Golgi Carriers, Not Lysosomes, Confer Lysosomal Properties to Pre-Degradative Organelles in Normal and Dystrophic Axons. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, S.M. Neuronal Lysosomes. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 697, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayar, V.; Chen, Y.; Sidransky, E.; Jagasia, R. Lysosomal Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration: Emerging Concepts and Methods. Trends Neurosci. 2022, 45, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Kuwahara, T. Targeting of Lysosomal Pathway Genes for Parkinson’s Disease Modification: Insights from Cellular and Animal Models. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 681369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, J.; Merino, P.; Nuckols, A.; Johnson, M.; Kukar, T. Lysosome Dysfunction as a Cause of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Lessons from Frontotemporal Dementia and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 154, 105360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, R.A.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Mechanisms of Autophagy–Lysosome Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 926–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Takeda, M.; Suzuki, H.; Morita, H.; Tada, K.; Hariguchi, S.; Nishimura, T. Lysosome Instability in Aged Rat Brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1989, 97, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, R.A. The Aging Lysosome: An Essential Catalyst for Late-Onset Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2020, 1868, 140443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sintes, R.; Ledesma, M.D.; Boya, P. Lysosomal Cell Death Mechanisms in Aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, A.M.; Dice, J.F. Age-Related Decline in Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 31505–31513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, D.J.; Decary, S.; Hong, Y.; Erusalimsky, J.D. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Reflects an Increase in Lysosomal Mass during Replicative Ageing of Human Endothelial Cells. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 3613–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, D.; Li, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, X. Lysosome Activity Is Modulated by Multiple Longevity Pathways and Is Important for Lifespan Extension in C. elegans. eLife 2020, 9, e55745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, C.J.; La Spada, A.R. TFEB Dysregulation as a Driver of Autophagy Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Disease: Molecular Mechanisms, Cellular Processes, and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 122, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Taverna, E. Vesicular Trafficking and Cell-Cell Communication in Neurodevelopment and Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1600034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Vooijs, M.A.; Keulers, T.G.H. Key Mechanisms in Lysosome Stability, Degradation and Repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2025, 45, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Carlsson, S.R.; Lystad, A.H. Lysosome-Associated CASM: From Upstream Triggers to Downstream Effector Mechanisms. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1559125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mony, V.K.; Benjamin, S.; O’Rourke, E.J. A Lysosome-Centered View of Nutrient Homeostasis. Autophagy 2016, 12, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Klionsky, D.J.; Shen, H.M. The Emerging Mechanisms and Functions of Microautophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.D.; Donaldson, J.G. Pathways and Mechanisms of Endocytic Recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, A.; Chen, C.C.H.; Banerjee, R.; Glodowski, D.; Audhya, A.; Rongo, C.; Grant, B.D. EHBP-1 Functions with RAB-10 during Endocytic Recycling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 2930–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Sato, K.; Liou, W.; Pant, S.; Harada, A.; Grant, B.D. Regulation of Endocytic Recycling by C. elegans Rab35 and Its Regulator RME-4, a Coated-Pit Protein. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.L.; Danson, C.M.; Lewis, P.A.; Zhao, L.; Riccardo, S.; Di Filippo, L.; Cacchiarelli, D.; Lee, D.; Cross, S.J.; Heesom, K.J.; et al. Multi-Omic Approach Characterizes the Neuroprotective Role of Retromer in Regulating Lysosomal Health. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, P.J.; Steinberg, F. To Degrade or Not to Degrade: Mechanisms and Significance of Endocytic Recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carosi, J.M.; Hein, L.K.; Sandow, J.J.; Dang, L.V.P.; Hattersley, K.; Denton, D.; Kumar, S.; Sargeant, T.J. Autophagy Captures the Retromer-TBC1D5 Complex to Inhibit Receptor Recycling. Autophagy 2023, 20, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loncle, N.; Agromayor, M.; Martin-Serrano, J.; Williams, D.W. An ESCRT Module Is Required for Neuron Pruning. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henne, W.M.; Buchkovich, N.J.; Emr, S.D. The ESCRT Pathway. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Perry, S.; Fan, Z.; Wang, B.; Loxterkamp, E.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Dickman, D.; Han, C. Tissue-Specific Knockout in the Drosophila Neuromuscular System Reveals ESCRT’s Role in Formation of Synapse-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, E.C.; Harris, K.P.; Blanchette, C.R.; Koles, K.; Del Signore, S.J.; Pescosolido, M.F.; Ermanoska, B.; Rozencwaig, M.; Soslowsky, R.C.; Parisi, M.J.; et al. ESCRT Disruption Provides Evidence against Trans-Synaptic Signaling via Extracellular Vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223, e202405025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzmann, D.J.; Odorizzi, G.; Emr, S.D. Receptor Downregulation and Multivesicular-Body Sorting. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rink, J.; Ghigo, E.; Kalaidzidis, Y.; Zerial, M. Rab Conversion as a Mechanism of Progression from Early to Late Endosomes. Cell 2005, 122, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, S.R. Rab GTPases: Master Regulators That Establish the Secretory and Endocytic Pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell 2017, 28, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, N.A.; Davis, L.J.; Luzio, J.P. Endolysosomes Are the Principal Intracellular Sites of Acid Hydrolase Activity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2233–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.C.; Uytterhoeven, V.; Kuenen, S.; Wang, Y.C.; Slabbaert, J.R.; Swerts, J.; Kasprowicz, J.; Aerts, S.; Verstreken, P. Reduced Synaptic Vesicle Protein Degradation at Lysosomes Curbs TBC1D24/Sky-Induced Neurodegeneration. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 207, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uytterhoeven, V.; Kuenen, S.; Kasprowicz, J.; Miskiewicz, K.; Verstreken, P. Loss of Skywalker Reveals Synaptic Endosomes as Sorting Stations for Synaptic Vesicle Proteins. Cell 2011, 145, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, P.; Zhu, M.; Beskow, A.; Vollmer, C.; Waites, C.L. Activity-Dependent Degradation of Synaptic Vesicle Proteins Requires Rab35 and the ESCRT Pathway. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 8668–8686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Yue, Z. Autophagy and Its Normal and Pathogenic States in the Brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 37, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maday, S.; Wallace, K.E.; Holzbaur, E.L.F. Autophagosomes Initiate Distally and Mature during Transport toward the Cell Soma in Primary Neurons. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.T.; Zhou, B.; Lin, M.Y.; Cai, Q.; Sheng, Z.H. Axonal Autophagosomes Recruit Dynein for Retrograde Transport through Fusion with Late Endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 209, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargbo-Hill, S.E.; Colón-Ramos, D.A. The Journey of the Synaptic Autophagosome: A Cell Biological Perspective. Neuron 2020, 105, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maday, S.; Holzbaur, E.L.F. Compartment-Specific Regulation of Autophagy in Primary Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 5933–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, M.; Waguri, S.; Chiba, T.; Murata, S.; Iwata, J.I.; Tanida, I.; Ueno, T.; Koike, M.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kominami, E.; et al. Loss of Autophagy in the Central Nervous System Causes Neurodegeneration in Mice. Nature 2006, 441, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, T.; Nakamura, K.; Matsui, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Nakahara, Y.; Suzuki-Migishima, R.; Yokoyama, M.; Mishima, K.; Saito, I.; Okano, H.; et al. Suppression of Basal Autophagy in Neural Cells Causes Neurodegenerative Disease in Mice. Nature 2006, 441, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, E.M.; Abou-Sleiman, P.M.; Caputo, V.; Muqit, M.M.K.; Harvey, K.; Gispert, S.; Ali, Z.; Del Turco, D.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Healy, D.G.; et al. Hereditary Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease Caused by Mutations in PINK1. Science 2004, 304, 1158–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, T.; Asakawa, S.; Hattori, N.; Matsumine, H.; Yamamura, Y.; Minoshima, S.; Yokochi, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Shimizu, N. Mutations in the Parkin Gene Cause Autosomal Recessive Juvenile Parkinsonism. Nature 1998, 392, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Guardia, C.M.; Pu, J.; Chen, Y.; Bonifacino, J.S. BORC Coordinates Encounter and Fusion of Lysosomes with Autophagosomes. Autophagy 2017, 13, 1648–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Vinardell, J.; Sandler, M.B.; De Pace, R.; Manzella-Lapeira, J.; Cougnoux, A.; Keyvanfar, K.; Introne, W.J.; Brzostowski, J.A.; Ward, M.E.; Gahl, W.A.; et al. LYST Deficiency Impairs Autophagic Lysosome Reformation in Neurons and Alters Lysosome Number and Size. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Nishimura, T.; Sakamaki, Y.; Itakura, E.; Hatta, T.; Natsume, T.; Mizushima, N. The HOPS Complex Mediates Autophagosome–Lysosome Fusion through Interaction with Syntaxin 17. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 1327–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, F.M.; Fleming, A.; Caricasole, A.; Bento, C.F.; Andrews, S.P.; Ashkenazi, A.; Füllgrabe, J.; Jackson, A.; Jimenez Sanchez, M.; Karabiyik, C.; et al. Autophagy and Neurodegeneration: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Neuron 2017, 93, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli-Daley, L.A.; Gamble, K.L.; Schultheiss, C.E.; Riddle, D.M.; West, A.B.; Lee, V.M.Y. Formation of α-Synuclein Lewy Neurite-like Aggregates in Axons Impedes the Transport of Distinct Endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 4010–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, M.M.; Zheng, B.; Lu, T.; Yan, Z.; Py, B.F.; Ng, A.; Xavier, R.J.; Li, C.; Yankner, B.A.; Scherzer, C.R.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Mechanisms Modulating Autophagy in Normal Brain Aging and in Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14164–14169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, J.O.; Yoo, S.M.; Ahn, H.H.; Nah, J.; Hong, S.H.; Kam, T.I.; Jung, S.; Jung, Y.K. Overexpression of Atg5 in Mice Activates Autophagy and Extends Lifespan. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.D.; Young, A.R.J.; Young, C.N.J.; Soilleux, E.J.; Fielder, E.; Weigand, B.M.; Lagnado, A.; Brais, R.; Ktistakis, N.T.; Wiggins, K.A.; et al. Temporal Inhibition of Autophagy Reveals Segmental Reversal of Ageing with Increased Cancer Risk. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Bourdenx, M.; Fujimaki, M.; Karabiyik, C.; Krause, G.J.; Lopez, A.; Martín-Segura, A.; Puri, C.; Scrivo, A.; Skidmore, J.; et al. The Different Autophagy Degradation Pathways and Neurodegeneration. Neuron 2022, 110, 935–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, A.M.; Dice, J.F. A Receptor for the Selective Uptake and Degradation of Proteins by Lysosomes. Science 1996, 273, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffi, G.T.; Botelho, R.J. Lysosome Fission: Planning for an Exit. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, J.; Itzhak, D.N.; Antrobus, R.; Borner, G.H.H.; Robinson, M.S. Role of the AP-5 Adaptor Protein Complex in Late Endosome-to-Golgi Retrieval. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2004411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagaraj, P.; Gautier-Stein, A.; Riedel, D.; Schomburg, C.; Cerdà, J.; Vollack, N.; Dosch, R. Souffle/Spastizin Controls Secretory Vesicle Maturation during Zebrafish Oogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirst, J.; Borner, G.H.H.; Edgar, J.; Hein, M.Y.; Mann, M.; Buchholz, F.; Antrobus, R.; Robinson, M.S. Interaction between AP-5 and the Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Proteins SPG11 and SPG15. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.; Torgersen, M.L.; Sandvig, K.; Simonsen, A. LYST Affects Lysosome Size and Quantity, but Not Trafficking or Degradation through Autophagy or Endocytosis. Traffic 2014, 15, 1390–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Haberman, A.; Tracy, C.; Ray, S.; Krämer, H. Drosophila Mauve Mutants Reveal a Role of LYST Homologs Late in the Maturation of Phagosomes and Autophagosomes. Traffic 2012, 13, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Rydzewski, N.; Hider, A.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, Q.; Cheng, X.; Xu, H. A Molecular Mechanism to Regulate Lysosome Motility for Lysosome Positioning and Tubulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratto, E.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Siefert, N.S.; Schneider, M.; Wittmann, M.; Helm, D.; Palm, W. Direct Control of Lysosomal Catabolic Activity by mTORC1 through Regulation of V-ATPase Assembly. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoncu, R.; Bar-Peled, L.; Efeyan, A.; Wang, S.; Sancak, Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTORC1 Senses Lysosomal Amino Acids through an Inside-out Mechanism That Requires the Vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science 2011, 334, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.C.; Hardie, D.G. AMPK: Sensing Glucose as Well as Cellular Energy Status. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.S.; Jiang, B.; Li, M.; Zhu, M.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wu, Y.Q.; Li, T.Y.; Liang, Y.; Lu, Z.; et al. The Lysosomal V-ATPase-Ragulator Complex Is a Common Activator for AMPK and mTORC1, Acting as a Switch between Catabolism and Anabolism. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.A.; Myers, J.T.; Swanson, J.A. pH-Dependent Regulation of Lysosomal Calcium in Macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Evans, E.; Morgan, A.J.; He, X.; Smith, D.A.; Elliot-Smith, E.; Sillence, D.J.; Churchill, G.C.; Schuchman, E.H.; Galione, A.; Platt, F.M. Niemann-Pick Disease Type C1 Is a Sphingosine Storage Disease That Causes Deregulation of Lysosomal Calcium. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.J.; Davis, L.C.; Galione, A. Imaging Approaches to Measuring Lysosomal Calcium. Methods Cell Biol. 2015, 126, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaello, A.; Mammucari, C.; Gherardi, G.; Rizzuto, R. Calcium at the Center of Cell Signaling: Interplay between Endoplasmic Reticulum, Mitochondria, and Lysosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 1035–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.P.; Cheng, X.; Mills, E.; Delling, M.; Wang, F.; Kurz, T.; Xu, H. The Type IV Mucolipidosis-Associated Protein TRPML1 Is an Endolysosomal Iron Release Channel. Nature 2008, 455, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, B.; Torres-Vidal, P.; Delrio-Lorenzo, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Aulestia, F.J.; Rojo-Ruiz, J.; Callejo, B.; McVeigh, B.M.; Keller, M.; Grimm, C.; et al. Direct Measurements of Luminal Ca2+ with Endo-Lysosomal GFP-Aequorin Reveal Functional IP3 Receptors. J. Cell Biol. 2025, 224, e202410094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.J.; Platt, F.M.; Lloyd-Evans, E.; Galione, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Endolysosomal Ca2+ Signalling in Health and Disease. Biochem. J. 2011, 439, 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Arige, V.; Saito, R.; Mu, Q.; Brailoiu, G.C.; Pereira, G.J.S.; Bolsover, S.R.; Keller, M.; Bracher, F.; Grimm, C.; et al. Two-Pore Channel-2 and Inositol Trisphosphate Receptors Coordinate Ca2+ Signals between Lysosomes and the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Cell Rep. 2023, 43, 113628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, R.M.; Zoncu, R. The Lysosome as a Regulatory Hub. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 32, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, D.L.; Di Paola, S.; Peluso, I.; Armani, A.; De Stefani, D.; Venditti, R.; Montefusco, S.; Scotto-Rosato, A.; Prezioso, C.; Forrester, A.; et al. Lysosomal Calcium Signalling Regulates Autophagy through Calcineurin and TFEB. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, J.; Yan, L.; Li, W.; He, X.; Ma, H. Chronic Neuronal Inactivity Utilizes the mTOR-TFEB Pathway to Drive Transcription-Dependent Autophagy for Homeostatic Up-Scaling. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 2631–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akwa, Y.; Di Malta, C.; Zallo, F.; Gondard, E.; Lunati, A.; Diaz-de-Grenu, L.Z.; Zampelli, A.; Boiret, A.; Santamaria, S.; Martinez-Preciado, M.; et al. Stimulation of Synaptic Activity Promotes TFEB-Mediated Clearance of Pathological MAPT/Tau in Cellular and Mouse Models of Tauopathies. Autophagy 2022, 19, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.C.; Ysselstein, D.; Krainc, D. Mitochondria-Lysosome Contacts Regulate Mitochondrial Fission via Rab7 GTP Hydrolysis. Nature 2018, 554, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Coukos, R.; Gao, F.; Krainc, D. Dysregulation of Organelle Membrane Contact Sites in Neurological Diseases. Neuron 2022, 110, 2386–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzollo, F.; More, S.; Vangheluwe, P.; Agostinis, P. The Lysosome as a Master Regulator of Iron Metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Wong, Y.C.; Krainc, D. Mitochondria-Lysosome Contacts Regulate Mitochondrial Ca2+ Dynamics via Lysosomal TRPML1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 19266–19275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, W.; Peng, T.; Wang, X.; Lian, X.; He, J.; Wang, C.; Xie, N. TBC1D15-Regulated Mitochondria–Lysosome Membrane Contact Exerts Neuroprotective Effects by Alleviating Mitochondrial Calcium Overload in Seizure. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Eaton, J.W.; Brunk, U.T. The Role of Lysosomes in Iron Metabolism and Recycling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Abarientos, A.; Hong, J.; Hashemi, S.H.; Yan, R.; Dräger, N.; Leng, K.; Nalls, M.A.; Singleton, A.B.; Xu, K.; et al. Genome-Wide CRISPRi/a Screens in Human Neurons Link Lysosomal Failure to Ferroptosis. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañeque, T.; Baron, L.; Müller, S.; Carmona, A.; Colombeau, L.; Versini, A.; Solier, S.; Gaillet, C.; Sindikubwabo, F.; Sampaio, J.L.; et al. Activation of Lysosomal Iron Triggers Ferroptosis in Cancer. Nature 2025, 642, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.J.; Deppmann, C.; Winckler, B. Emerging Roles of Neuronal Extracellular Vesicles at the Synapse. Neuroscientist 2024, 30, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacino, J.S.; Neefjes, J. Moving and Positioning the Endolysosomal System. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfel-Becker, T.; Roney, J.C.; Cheng, X.T.; Li, S.; Cuddy, S.R.; Sheng, Z.H. Neuronal Soma-Derived Degradative Lysosomes Are Continuously Delivered to Distal Axons to Maintain Local Degradation Capacity. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 51–64.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, M.S.; Sancho, L.; Slepak, N.; Boassa, D.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Bloodgood, B.L.; Patrick, G.N. Activity-Dependent Trafficking of Lysosomes in Dendrites and Dendritic Spines. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 2499–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.C.; Fernandopulle, M.S.; Wang, G.; Choi, H.; Hao, L.; Drerup, C.M.; Patel, R.; Qamar, S.; Nixon-Abell, J.; Shen, Y.; et al. RNA Granules Hitchhike on Lysosomes for Long-Distance Transport, Using Annexin A11 as a Molecular Tether. Cell 2019, 179, 147–164.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Van Tartwijk, F.W.; Lin, J.Q.; Nijenhuis, W.; Parutto, P.; Fantham, M.; Christensen, C.N.; Avezov, E.; Holt, C.E.; Tunnacliffe, A.; et al. The Structure and Global Distribution of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Network Are Actively Regulated by Lysosomes. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gómez-Sintes, R.; Boya, P. Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization and Cell Death. Traffic 2018, 19, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A.; Scanavachi, G.; Somerville, E.; Saminathan, A.; Nair, A.; Bango Da Cunha Correia, R.F.; Aylan, B.; Sitarska, E.; Oikonomou, A.; Hatzakis, N.S.; et al. Neuronal Constitutive Endolysosomal Perforations Enable α-Synuclein Aggregation by Internalized PFFs. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 224, e202401136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehay, B.; Bové, J.; Rodríguez-Muela, N.; Perier, C.; Recasens, A.; Boya, P.; Vila, M. Pathogenic Lysosomal Depletion in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 12535–12544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, M.; Bové, J.; Dehay, B.; Rodríguez-Muela, N.; Boya, P. Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization in Parkinson Disease. Autophagy 2011, 7, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabandé-Rodríguez, E.; Boya, P.; Labrador, V.; Dotti, C.G.; Ledesma, M.D. High Sphingomyelin Levels Induce Lysosomal Damage and Autophagy Dysfunction in Niemann Pick Disease Type A. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavin, W.P.; Bousset, L.; Green, Z.C.; Chu, Y.; Skarpathiotis, S.; Chaney, M.J.; Kordower, J.H.; Melki, R.; Campbell, E.M. Endocytic Vesicle Rupture Is a Conserved Mechanism of Cellular Invasion by Amyloid Proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 134, 629–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Kirchner, P.; Bug, M.; Grum, D.; Koerver, L.; Schulze, N.; Poehler, R.; Dressler, A.; Fengler, S.; Arhzaouy, K.; et al. VCP/P97 Cooperates with YOD1, UBXD1 and PLAA to Drive Clearance of Ruptured Lysosomes by Autophagy. EMBO J. 2016, 36, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, J.; Salinas, J.E.; Wheaton, R.p.; Poolsup, S.; Allers, L.; Rosas-Lemus, M.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Q.; Pu, J.; Salemi, M.; et al. Calcium Signaling from Damaged Lysosomes Induces Cytoprotective Stress Granules. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 6410–6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakore, P.; Pritchard, H.A.T.; Griffin, C.S.; Yamasaki, E.; Drumm, B.T.; Lane, C.; Sanders, K.M.; Feng Earley, Y.; Earley, S. TRPML1 Channels Initiate Ca2+ Sparks in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eaba1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskelinen, E.L. To Be or Not to Be? Examples of Incorrect Identification of Autophagic Compartments in Conventional Transmission Electron Microscopy of Mammalian Cells. Autophagy 2008, 4, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Beek, J.; de Heus, C.; Liv, N.; Klumperman, J. Quantitative Correlative Microscopy Reveals the Ultrastructural Distribution of Endogenous Endosomal Proteins. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 221, e202106044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermie, J.; Liv, N.; ten Brink, C.; van Donselaar, E.G.; Müller, W.H.; Schieber, N.L.; Schwab, Y.; Gerritsen, H.C.; Klumperman, J. Single Organelle Dynamics Linked to 3D Structure by Correlative Live-Cell Imaging and 3D Electron Microscopy. Traffic 2018, 19, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giepmans, B.N.G.; Deerinck, T.J.; Smarr, B.L.; Jones, Y.Z.; Ellisman, M.H. Correlated Light and Electron Microscopic Imaging of Multiple Endogenous Proteins Using Quantum Dots. Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao-Cheng, J.H.; Crocker, V.; Moreira, S.L.; Azzam, R. Optimization of Protocols for Pre-Embedding Immunogold Electron Microscopy of Neurons in Cell Cultures and Brains. Mol. Brain 2021, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacO, B.; Cantoni, M.; Holtmaat, A.; Kreshuk, A.; Hamprecht, F.A.; Knott, G.W. Semiautomated Correlative 3D Electron Microscopy of in Vivo-Imaged Axons and Dendrites. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1354–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet-Ponce, L.; Beilina, A.; Williamson, C.D.; Lindberg, E.; Kluss, J.H.; Saez-Atienzar, S.; Landeck, N.; Kumaran, R.; Mamais, A.; Bleck, C.K.E.; et al. LRRK2 Mediates Tubulation and Vesicle Sorting from Lysosomes. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazik, J.; Ylä-Anttila, P.; Vihinen, H.; Jokitalo, E.; Eskelinen, E.L. Ultrastructural Relationship of the Phagophore with Surrounding Organelles. Autophagy 2015, 11, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissig, C.; Hurbain, I.; Raposo, G.; van Niel, G. PIKfyve Activity Regulates Reformation of Terminal Storage Lysosomes from Endolysosomes. Traffic 2017, 18, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.C.; Digilio, L.; McMahon, L.P.; Garcia, A.D.R.; Winckler, B. Degradation of Dendritic Cargos Requires Rab7-Dependent Transport to Somatic Lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 3141–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.T.; Xie, Y.X.; Zhou, B.; Huang, N.; Farfel-Becker, T.; Sheng, Z.H. Characterization of LAMP1-Labeled Nondegradative Lysosomal and Endocytic Compartments in Neurons. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 3127–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, V.V.; Maday, S. Neuronal Endosomes to Lysosomes: A Journey to the Soma. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 2977–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Richardson, C.E. Expansion of Lysosomal Capacity in Early Adult Neurons Driven by TFEB/HLH-30 Protects Dendrite Maintenance during Aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3002957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snead, A.M.; Gowrishankar, S. Loss of MAPK8IP3 Affects Endocytosis in Neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 828071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiliaev, N.; Baumberger, S.; Richardson, C.E. Analysis In Vivo Using a New Method, ARGO (Analysis of Red Green Offset), Reveals Complexity and Cell-Type Specificity in Presynaptic Turnover of Synaptic Vesicle Protein Synaptogyrin/SNG-1. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulovaite, E.; Qiu, Z.; Kratschke, M.; Zgraj, A.; Fricker, D.G.; Tuck, E.J.; Gokhale, R.; Koniaris, B.; Jami, S.A.; Merino-Serrais, P.; et al. A Brain Atlas of Synapse Protein Lifetime across the Mouse Lifespan. Neuron 2022, 110, 4057–4073.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falace, A.; Volpedo, G.; Scala, M.; Zara, F.; Striano, P.; Fassio, A. V-ATPase Dysfunction in the Brain: Genetic Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cells 2024, 13, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overly, C.C.; Lee, K.D.; Berthiaume, E.; Hollenbeck, P.J. Quantitative Measurement of Intraorganelle pH in the Endosomal-Lysosomal Pathway in Neurons by Using Ratiometric Imaging with Pyranine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 3156–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Ostrowski, P.; Jaumouillé, V.; Grinstein, S. The Position of Lysosomes within the Cell Determines Their Luminal pH. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 212, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noorden, C.J.F. Imaging Enzymes at Work: Metabolic Mapping by Enzyme Histochemistry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2010, 58, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Yang, C. Exploring Lysosomal Biology: Current Approaches and Methods. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, L.K.; Mazzulli, J.R. Analysis of Lysosomal Hydrolase Trafficking and Activity in Human iPSC-Derived Neuronal Models. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, M.D.; Kallemeijn, W.W.; Aten, J.; Li, K.Y.; Strijland, A.; Donker-Koopman, W.E.; Van Den Nieuwendijk, A.M.C.H.; Bleijlevens, B.; Kramer, G.; Florea, B.I.; et al. Ultrasensitive In Situ Visualization of Active Glucocerebrosidase Molecules. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tan, J.X. Lysosomal Quality Control: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Trends Cell Biol. 2023, 33, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.T.; Torres-Vidal, P.; Calvo, B.; Rodriguez, C.; Delrio-Lorenzo, A.; Rojo-Ruiz, J.; Garcia-Sancho, J.; Patel, S. Use of Aequorin-Based Indicators for Monitoring Ca2+ in Acidic Organelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2023, 1870, 119481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, J.; Ohkura, M.; Imoto, K. A High Signal-to-Noise Ca2+ Probe Composed of a Single Green Fluorescent Protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, V.; Potenza, D.M.; Denti, F.; Vullo, S.; Gagliano, G.; Tognolina, M.; Guerra, G.; Pinton, P.; Genazzani, A.A.; Mapelli, L.; et al. A Novel Ca2+-Mediated Cross-Talk between Endoplasmic Reticulum and Acidic Organelles: Implications for NAADP-Dependent Ca2+ Signalling. Cell Calcium 2015, 57, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.C.; Vest, R.; Prado, M.A.; Wilson-Grady, J.; Paulo, J.A.; Shibuya, Y.; Moran-Losada, P.; Lee, T.T.; Luo, J.; Gygi, S.P.; et al. Proteostasis and Lysosomal Repair Deficits in Transdifferentiated Neurons of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2025, 27, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rietz, H.; Hedlund, H.; Wilhelmson, S.; Nordenfelt, P.; Wittrup, A. Imaging Small Molecule-Induced Endosomal Escape of SiRNA. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aits, S.; Kricker, J.; Liu, B.; Ellegaard, A.M.; Hämälistö, S.; Tvingsholm, S.; Corcelle-Termeau, E.; Høgh, S.; Farkas, T.; Jonassen, A.H.; et al. Sensitive Detection of Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization by Lysosomal Galectin Puncta Assay. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1408–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Claude-Taupin, A.; Gu, Y.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Bissa, B.; Mudd, M.H.; Allers, L.; Pallikkuth, S.; Lidke, K.A.; et al. Galectin-3 Coordinates a Cellular System for Lysosomal Repair and Removal. Dev. Cell 2019, 52, 69–87.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, O.; Saran, E.; Freeman, S.A. The Spectrum of Lysosomal Stress and Damage Responses: From Mechanosensing to Inflammation. EMBO Rep. 2025, 26, 1425–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Cedillos, R.; Choyke, S.; Lukic, Z.; McGuire, K.; Marvin, S.; Burrage, A.M.; Sudholt, S.; Rana, A.; O’Connor, C.; et al. Alpha-Synuclein Induces Lysosomal Rupture and Cathepsin Dependent Reactive Oxygen Species Following Endocytosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.; Jepson, T.; Shukla, S.; Maya-Romero, A.; Kampmann, M.; Xu, K.; Hurley, J.H. Tau Fibrils Induce Nanoscale Membrane Damage and Nucleate Cytosolic Tau at Lysosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2315690121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämälistö, S.; Stahl, J.L.; Favaro, E.; Yang, Q.; Liu, B.; Christoffersen, L.; Loos, B.; Guasch Boldú, C.; Joyce, J.A.; Reinheckel, T.; et al. Spatially and Temporally Defined Lysosomal Leakage Facilitates Mitotic Chromosome Segregation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnock, R.; Yalci, K.; Palmfeldt, J.; Jäättelä, M.; Liu, B.; Carroll, B. TFEB-dependent Lysosome Biogenesis Is Required for Senescence. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e111241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narita, M.; Young, A.R.J.; Arakawa, S.; Samarajiwa, S.A.; Nakashima, T.; Yoshida, S.; Hong, S.; Berry, L.S.; Reichelt, S.; Ferreira, M.; et al. Spatial Coupling of mTOR and Autophagy Augments Secretory Phenotypes. Science 2011, 332, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrinha, T.; Cunha, C.; Hall, M.J.; Lopes-da-Silva, M.; Seabra, M.C.; Guimas Almeida, C. Deacidification of Endolysosomes by Neuronal Aging Drives Synapse Loss. Traffic 2023, 24, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-García, A.; Kun, A.; Calero, O.; Medina, M.; Calero, M. An Overview of the Role of Lipofuscin in Age-Related Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terman, A.; Brunk, U.T. Lipofuscin: Mechanisms of Formation and Increase with Age. APMIS 1998, 106, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunk, U.T.; Terman, A. Lipofuscin: Mechanisms of Age-Related Accumulation and Influence on Cell Function. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldensperger, T.; Jung, T.; Heinze, T.; Schwerdtle, T.; Höhn, A.; Grune, T. The Age Pigment Lipofuscin Causes Oxidative Stress, Lysosomal Dysfunction, and Pyroptotic Cell Death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 225, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, M.S.; Kasturi, P.; Hartl, F.U. The Proteostasis Network and Its Decline in Ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.C.; Nelson, A.; Hartenstein, V. Structural Aspects of the Aging Invertebrate Brain. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 383, 931–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hivare, P.; Mujmer, K.; Swarup, G.; Gupta, S.; Bhatia, D. Endocytic Pathways of Pathogenic Protein Aggregates in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Traffic 2023, 24, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.L.; Lee, V.M.Y. Seeding of Normal Tau by Pathological Tau Conformers Drives Pathogenesis of Alzheimer-like Tangles. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 15317–15331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desplats, P.; Lee, H.J.; Bae, E.J.; Patrick, C.; Rockenstein, E.; Crews, L.; Spencer, B.; Masliah, E.; Lee, S.J. Inclusion Formation and Neuronal Cell Death through Neuron-to-Neuron Transmission of α-Synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13010–13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuda, K.; Ikenaka, K.; Kuma, A.; Doi, J.; Aguirre, C.; Wang, N.; Ajiki, T.; Choong, C.J.; Kimura, Y.; Badawy, S.M.M.; et al. Lysophagy Protects against Propagation of α-Synuclein Aggregation through Ruptured Lysosomal Vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2312306120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluever, V.; Russo, B.; Mandad, S.; Kumar, N.H.; Alevra, M.; Ori, A.; Rizzoli, S.O.; Urlaub, H.; Schneider, A.; Fornasiero, E.F. Protein Lifetimes in Aged Brains Reveal a Proteostatic Adaptation Linking Physiological Aging to Neurodegeneration. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.; Laugks, U.; Heckmann, M.; Asan, E.; Neuser, K. Aging Drosophila Melanogaster Display Altered Pre- and Postsynaptic Ultrastructure at Adult Neuromuscular Junctions. J. Comp. Neurol. 2015, 523, 2457–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaro, S.N.; Soares, J.C.; König, B. Comparative Structural Analysis of Neuromuscular Junctions in Mice at Different Ages. Ann. Anat. Anat. Anz. 1998, 180, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrinha, T.; Martinsson, I.; Gomes, R.; Terrasso, A.P.; Gouras, G.K.; Almeida, C.G. Upregulation of APP Endocytosis by Neuronal Aging Drives Amyloid-Dependent Synapse Loss. J. Cell Sci. 2021, 134, jcs255752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaqati, M.; Thomas, R.S.; Kidd, E.J. Proteins Involved in Endocytosis Are Upregulated by Ageing in the Normal Human Brain: Implications for the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.E.; Yee, C.; Shen, K. A Hormone Receptor Pathway Cell-Autonomously Delays Neuron Morphological Aging by Suppressing Endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, H.; Amano, T.; Sastradipura, D.F.; Yoshimine, Y.; Tsukuba, T.; Tanabe, K.; Hirotsu, I.; Ohono, T.; Yamamoto, K. Increased Expression of Cathepsins E and D in Neurons of the Aged Rat Brain and Their Colocalization with Lipofuscin and Carboxy-Terminal Fragments of Alzheimer Amyloid Precursor Protein. J. Neurochem. 1997, 68, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, S.I. Age-Related Changes in Ultrastructural Features of Cathepsin B- and D-Containing Neurons in Rat Cerebral Cortex. Brain Res. 1999, 844, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E.M.; Smith, G.A.; Park, E.; Cao, H.; Brown, E.; Hallett, P.; Isacson, O. Progressive Decline of Glucocerebrosidase in Aging and Parkinson’s Disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2015, 2, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gegg, M.E.; Burke, D.; Heales, S.J.R.; Cooper, J.M.; Hardy, J.; Wood, N.W.; Schapira, A.H.V. Glucocerebrosidase Deficiency in Substantia Nigra of Parkinson Disease Brains. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, P.J.; Huebecker, M.; Brekk, O.R.; Moloney, E.B.; Rocha, E.M.; Priestman, D.A.; Platt, F.M.; Isacson, O. Glycosphingolipid Levels and Glucocerebrosidase Activity Are Altered in Normal Aging of the Mouse Brain. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 67, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Muthu Karuppan, M.K.; Devadoss, D.; Nair, M.; Chand, H.S.; Lakshmana, M.K. TFEB Protein Expression Is Reduced in Aged Brains and Its Overexpression Mitigates Senescence-Associated Biomarkers and Memory Deficits in Mice. Neurobiol. Aging 2021, 106, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, L.R.; De Magalhaes Filho, C.D.; McQuary, P.R.; Chu, C.C.; Visvikis, O.; Chang, J.T.; Gelino, S.; Ong, B.; Davis, A.E.; Irazoqui, J.E.; et al. The TFEB Orthologue HLH-30 Regulates Autophagy and Modulates Longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.K.; Zhang, P.; Kodur, A.; Erturk, I.; Burns, C.M.; Kenyon, C.; Miller, R.A.; Endicott, S.J. LAMP2A, and Other Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy Related Proteins, Do Not Decline with Age in Genetically Heterogeneous UM-HET3 Mice. Aging 2023, 15, 4685–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdenx, M.; Martín-Segura, A.; Scrivo, A.; Rodriguez-Navarro, J.A.; Kaushik, S.; Tasset, I.; Diaz, A.; Storm, N.J.; Xin, Q.; Juste, Y.R.; et al. Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy Prevents Collapse of the Neuronal Metastable Proteome. Cell 2021, 184, 2696–2714.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.; Belsky, D.W.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Miller, G.W. An Exposomic Framework to Uncover Environmental Drivers of Aging. Exposome 2022, 2, osac002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandics, T.; Major, D.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Szarvas, Z.; Peterfi, A.; Mukli, P.; Gulej, R.; Ungvari, A.; Fekete, M.; Tompa, A.; et al. Exposome and Unhealthy Aging: Environmental Drivers from Air Pollution to Occupational Exposures. Geroscience 2023, 45, 3381–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, A.P. Ageing and the Free Radical Theory. Respir. Physiol. 2001, 128, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, R.E.; Pearson-Smith, J.N.; Huynh, C.Q.; Fabisiak, T.; Liang, L.P.; Aivazidis, S.; High, B.A.; Buscaglia, G.; Corrigan, T.; Valdez, R.; et al. Neuron-Specific Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Results in Epilepsy, Glucose Dysregulation and a Striking Astrocyte Response. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 158, 105470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivtoraiko, V.N.; Stone, S.L.; Roth, K.A.; Shacka, J.J. Oxidative Stress and Autophagy in the Regulation of Lysosome-Dependent Neuron Death. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagda, R.K.; Cherra, S.J.; Kulich, S.M.; Tandon, A.; Park, D.; Chu, C.T. Loss of PINK1 Function Promotes Mitophagy through Effects on Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Fission. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 13843–13855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, T.Y.; Cho, J.H.; Koh, J.Y. Zinc and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal Mediate Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization Induced by H2O2 in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 3114–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foret, M.K.; Orciani, C.; Welikovitch, L.A.; Huang, C.; Cuello, A.C.; Do Carmo, S. Early Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Aβ-Burdened Hippocampal Neurons in an Alzheimer’s-like Transgenic Rat Model. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.R.; Jankowski, C.S.R.; Marshall, R.; Nair, R.; Gómez, N.M.; Alnemri, A.; Liu, Y.; Erler, E.; Ferrante, J.; Song, Y.; et al. Oxidative Stress Induces Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization and Ceramide Accumulation in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. DMM Dis. Models Mech. 2023, 16, dmm050066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandlur, A.; Satyamoorthy, K.; Gangadharan, G. Oxidative Stress in Cognitive and Epigenetic Aging: A Retrospective Glance. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamsler, A.; Avital, A.; Greenberger, V.; Segal, M. Aged SOD Overexpressing Mice Exhibit Enhanced Spatial Memory While Lacking Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007, 9, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Serrano, F.; Oury, T.D.; Klann, E. Aging-Dependent Alterations in Synaptic Plasticity and Memory in Mice That Overexpress Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 3933–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Liu, I.Y.; Bi, X.; Thompson, R.F.; Doctrow, S.R.; Malfroy, B.; Baudry, M. Reversal of Age-Related Learning Deficits and Brain Oxidative Stress in Mice with Superoxide Dismutase/Catalase Mimetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8526–8531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, R.S.; Ku, H.H.; Agarwal, S.; Forster, M.J.; Lal, H. Oxidative Damage, Mitochondrial Oxidant Generation and Antioxidant Defenses during Aging and in Response to Food Restriction in the Mouse. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1994, 74, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.H.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. Parkinson’s Disease: A Dual-Hit Hypothesis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2007, 33, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Raina, A.K.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Two-Hit Hypothesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.D.; Dolatabadi, N.; Chan, S.F.; Zhang, X.; Akhtar, M.W.; Parker, J.; Soldner, F.; Sunico, C.R.; Nagar, S.; Talantova, M.; et al. Isogenic Human iPSC Parkinson’s Model Shows Nitrosative Stress-Induced Dysfunction in MEF2-PGC1α Transcription. Cell 2013, 155, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, S.D.; Posimo, J.M.; Mason, D.M.; Hutchison, D.F.; Leak, R.K. Synergistic Stress Exacerbation in Hippocampal Neurons: Evidence Favoring the Dual-Hit Hypothesis of Neurodegeneration. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrone Parfitt, G.; Coccia, E.; Goldman, C.; Whitney, K.; Reyes, R.; Sarrafha, L.; Nam, K.H.; Sohail, S.; Jones, D.R.; Crary, J.F.; et al. Disruption of Lysosomal Proteolysis in Astrocytes Facilitates Midbrain Organoid Proteostasis Failure in an Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease Model. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiki, T.; Weikel, K.A.; Jiao, W.; Shang, F.; Caceres, A.; Pawlak, D.; Handa, J.T.; Brownlee, M.; Nagaraj, R.; Taylor, A. Glycation-Altered Proteolysis as a Pathobiologic Mechanism That Links Dietary Glycemic Index, Aging, and Age-Related Disease (in Non Diabetics). Aging Cell 2011, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitek, M.P.; Bhattacharya, K.; Glendening, J.M.; Stopa, E.; Vlassara, H.; Bucala, R.; Manogue, K.; Cerami, A. Advanced Glycation End Products Contribute to Amyloidosis in Alzheimer Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 4766–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Taneda, S.; Richey, P.L.; Miyata, S.; Yan, S.D.; Stern, D.; Sayre, L.M.; Monnier, V.M.; Perry, G. Advanced Maillard Reaction End Products Are Associated with Alzheimer Disease Pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 5710–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, R.R.; Martín-Segura, A.; Santiago-Fernández, O.; Sereda, R.; Lindenau, K.; McCabe, M.; Macho-González, A.; Jafari, M.; Scrivo, A.; Gomez-Sintes, R.; et al. Sex-Specific and Cell-Type-Specific Changes in Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy across Tissues during Aging. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.R.; Sun, J.; Petitgas, C.; Mesquita, A.; Dulac, A.; Robin, M.; Mollereau, B.; Jenny, A.; Chérif-Zahar, B.; Birman, S. The Lysosomal Membrane Protein LAMP2A Promotes Autophagic Flux and Prevents SNCA-Induced Parkinson Disease-like Symptoms in the Drosophila Brain. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1898–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.W. Regulated Secretion of Conventional Lysosomes. Trends Cell Biol. 2000, 10, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancini, B.; Buratta, S.; Delo, F.; Sagini, K.; Chiaradia, E.; Pellegrino, R.M.; Emiliani, C.; Urbanelli, L. Lysosomal Exocytosis: The Extracellular Role of an Intracellular Organelle. Membranes 2020, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, D.L.; Fraldi, A.; Bouche, V.; Annunziata, F.; Mansueto, G.; Spampanato, C.; Puri, C.; Pignata, A.; Martina, J.A.; Sardiello, M.; et al. Transcriptional Activation of Lysosomal Exocytosis Promotes Cellular Clearance. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, S.; Marsh, J.A.; Horie, K.; Sato, C.; Ballabio, A.; Karch, C.M.; Holtzman, D.M.; Zheng, H. TFEB Regulates Lysosomal Exocytosis of Tau and Its Loss of Function Exacerbates Tau Pathology and Spreading. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 26, 5925–5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Baixauli, F.; Mittelbrunn, M.; Fernández-Delgado, I.; Torralba, D.; Moreno-Gonzalo, O.; Baldanta, S.; Enrich, C.; Guerra, S.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. ISGylation Controls Exosome Secretion by Promoting Lysosomal Degradation of MVB Proteins. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, J.R.; Manna, P.T.; Nishimura, S.; Banting, G.; Robinson, M.S. Tetherin Is an Exosomal Tether. eLife 2016, 5, e17180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chitiprolu, M.; Roncevic, L.; Javalet, C.; Hemming, F.J.; Trung, M.T.; Meng, L.; Latreille, E.; Tanese de Souza, C.; McCulloch, D.; et al. Atg5 Disassociates the V1V0-ATPase to Promote Exosome Production and Tumor Metastasis Independent of Canonical Macroautophagy. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 716–730.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melentijevic, I.; Toth, M.L.; Arnold, M.L.; Guasp, R.J.; Harinath, G.; Nguyen, K.C.; Taub, D.; Parker, J.A.; Neri, C.; Gabel, C.V.; et al. C. elegans Neurons Jettison Protein Aggregates and Mitochondria Under Neurotoxic Stress. Nature 2017, 542, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Arnold, M.L.; Lange, C.M.; Sun, L.H.; Broussalian, M.; Doroodian, S.; Ebata, H.; Choy, E.H.; Poon, K.; Moreno, T.M.; et al. Autophagy Protein ATG-16.2 and Its WD40 Domain Mediate the Beneficial Effects of Inhibiting Early-Acting Autophagy Genes in C. elegans Neurons. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Zhang, Y.; Seegobin, S.P.; Pruvost, M.; Wang, Q.; Purtell, K.; Zhang, B.; Yue, Z. Microglia Clear Neuron-Released α-Synuclein via Selective Autophagy and Prevent Neurodegeneration. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldner, I.H.; Wagner, V.P.; Moran-Losada, P.; Shi, S.M.; Chen, K.; Meese, B.T.; Oh, H.; Guen, Y.L.; Lu, N.; Wong, P.S.; et al. Synaptic Proteins That Aggregate and Degrade Slower with Aging Accumulate in Microglia. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, L.; Honsho, M.; Zahn, T.R.; Keller, P.; Geiger, K.D.; Verkade, P.; Simons, K. Alzheimer’s Disease β-Amyloid Peptides Are Released in Association with Exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11172–11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins, H.M.; Xu, Y.; Biby, S.; Zhang, S. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway: A Review of Mechanisms and Inhibitors for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 879021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulen, M.F.; Samson, N.; Keller, A.; Schwabenland, M.; Liu, C.; Glück, S.; Thacker, V.V.; Favre, L.; Mangeat, B.; Kroese, L.J.; et al. CGAS–STING Drives Ageing-Related Inflammation and Neurodegeneration. Nature 2023, 620, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.X.; Finkel, T. Lysosomes in Senescence and Aging. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e57265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meikle, P.J.; Hopwood, J.J.; Clague, A.E.; Carey, W.F. Prevalence of Lysosomal Storage Disorders. JAMA 1999, 281, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futerman, A.H.; Van Meer, G. The Cell Biology of Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.A.; Miranda, C.O.; Sousa, V.F.; Santos, T.E.; Malheiro, A.R.; Solomon, M.; Maegawa, G.H.; Brites, P.; Sousa, M.M. Early Axonal Loss Accompanied by Impaired Endocytosis, Abnormal Axonal Transport, and Decreased Microtubule Stability Occur in the Model of Krabbe’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 66, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressey, S.N.R.; Smith, D.A.; Wong, A.M.S.; Platt, F.M.; Cooper, J.D. Early Glial Activation, Synaptic Changes and Axonal Pathology in the Thalamocortical System of Niemann–Pick Type C1 Mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 45, 1086–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavetsky, L.; Green, K.K.; Boyle, B.R.; Yousufzai, F.A.K.; Padron, Z.M.; Melli, S.E.; Kuhnel, V.L.; Jackson, H.M.; Blanco, R.E.; Howell, G.R.; et al. Increased Interactions and Engulfment of Dendrites by Microglia Precede Purkinje Cell Degeneration in a Mouse Model of Niemann Pick Type-C. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjala, V.A.; Abyadeh, M.; Klimek, I.; Tyshkovskiy, A.; Oz, N.; Castro, J.P.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Newton, J.; Kaya, A. Short-Lived Niemann-Pick Type C Mice with Accelerated Brain Aging as a Novel Model for Alzheimer’s Disease Research. Neural Regen. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. Endosome Function and Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowrishankar, S.; Wu, Y.; Ferguson, S.M. Impaired JIP3-Dependent Axonal Lysosome Transport Promotes Amyloid Plaque Pathology. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 3291–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Yu, W.H.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.; Mohan, P.S.; Peterhoff, C.M.; Wolfe, D.M.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Massey, A.C.; Sovak, G.; et al. Lysosomal Proteolysis and Autophagy Require Presenilin 1 and Are Disrupted by Alzheimer-Related PS1 Mutations. Cell 2010, 141, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, B.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.; Platt, F.M.; Wegiel, J.; Yu, W.H.; Nixon, R.A. Autophagy Induction and Autophagosome Clearance in Neurons: Relationship to Autophagic Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6926–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacurcio, D.J.; Nixon, R.A. Disorders of Lysosomal Acidification—The Emerging Role of v-ATPase in Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallings, R.; Connor-Robson, N.; Wade-Martins, R. LRRK2 Interacts with the Vacuolar-Type H+-ATPase Pump A1 Subunit to Regulate Lysosomal Function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 2696–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Congdon, E.E.; Wu, J.W.; Myeku, N.; Figueroa, Y.H.; Herman, M.; Marinec, P.S.; Gestwicki, J.E.; Dickey, C.A.; Yu, W.H.; Duff, K.E. Methylthioninium Chloride (Methylene Blue) Induces Autophagy and Attenuates Tauopathy in Vitro and in Vivo. Autophagy 2012, 8, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, S.K.; Walker, J.; Sah, E.; Bennett, E.; Atrian, F.; Frost, B.; Woost, B.; Bennett, R.E.; Orr, T.C.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Profiling Senescent Cells in Human Brains Reveals Neurons with CDKN2D/P19 and Tau Neuropathology. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Gill, J.S.; Bansal, P.K.; Deshmukh, R. Neuroinflammation—A Major Cause for Striatal Dopaminergic Degeneration in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 381, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, J.; Mendsaikhan, A.; Taylor, G.; Merino, P.; Nandy, S.; Wang, M.; Araujo, L.T.; Ryu, D.; Holler, C.; Thompson, B.M.; et al. Granulins Rescue Inflammation, Lysosome Dysfunction, Lipofuscin, and Neuropathology in a Mouse Model of Progranulin Deficiency. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, M.; I Rojo, A.; Manda, G.; Boscá, L.; Cuadrado, A. Inflammation in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2020, 9, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liénard, C.; Pintart, A.; Bomont, P. Neuronal Autophagy: Regulations and Implications in Health and Disease. Cells 2024, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.Y.; Hansen, M.; Kumsta, C. Molecular Mechanisms of Autophagy Decline during Aging. Cells 2024, 13, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, G.; Tavernarakis, N. Molecular Basis of Neuronal Autophagy in Ageing: Insights from Caenorhabditis elegans. Cells 2021, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, E.T.; Pyo, J.H.; Walker, D.W. Neuronal Induction of BNIP3-Mediated Mitophagy Slows Systemic Aging in Drosophila. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavoe, A.K.H.; Gopal, P.P.; Gubas, A.; Tooze, S.A.; Holzbaur, E.L.F. Expression of WIPI2B Counteracts Age-Related Decline in Autophagosome Biogenesis in Neurons. eLife 2019, 8, e44219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsong, H.; Holzbaur, E.L.F.; Stavoe, A.K.H. Aging Differentially Affects Axonal Autophagosome Formation and Maturation. Autophagy 2023, 19, 3079–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Oba, M.; Suzuki, M.; Takahashi, A.; Yamamuro, T.; Fujiwara, M.; Ikenaka, K.; Minami, S.; Tabata, N.; Yamamoto, K.; et al. Suppression of Autophagic Activity by Rubicon Is a Signature of Aging. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.T.; Kumsta, C.; Hellman, A.B.; Adams, L.M.; Hansen, M. Spatiotemporal Regulation of Autophagy during Caenorhabditis elegans Aging. eLife 2017, 6, e18459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappe, A.; McWilliams, T.G. Mitophagy in the Aging Nervous System. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 978142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Feng, L.; Li, J.; Lan, X.; Lixiang, A.; Lv, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L. The Alteration of Autophagy and Apoptosis in the Hippocampus of Rats with Natural Aging-Dependent Cognitive Deficits. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 334, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, Y.; Schmauck-Medina, T.; Hansen, M.; Morimoto, R.I.; Simon, A.K.; Bjedov, I.; Palikaras, K.; Simonsen, A.; Johansen, T.; Tavernarakis, N.; et al. Autophagy in Healthy Aging and Disease. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Arias, E.; Kwon, H.; Lopez, N.M.; Athonvarangkul, D.; Sahu, S.; Schwartz, G.J.; Pessin, J.E.; Singh, R. Loss of Autophagy in Hypothalamic POMC Neurons Impairs Lipolysis. EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, A.; Cumming, R.C.; Brech, A.; Isakson, P.; Schubert, D.R.; Finley, K.D. Promoting Basal Levels of Autophagy in the Nervous System Enhances Longevity and Oxidant Resistance in Adult Drosophila. Autophagy 2008, 4, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Zhang, H. Autophagosome Maturation: An Epic Journey from the ER to Lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, W.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Cui, Y. Upregulation of Neuronal ER-Phagy Improves Organismal Fitness and Alleviates APP Toxicity. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeisser, K.; Parker, J.A. Nicotinamide-N-Methyltransferase Controls Behavior, Neurodegeneration and Lifespan by Regulating Neuronal Autophagy. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhukel, A.; Beuschel, C.B.; Maglione, M.; Lehmann, M.; Juhász, G.; Madeo, F.; Sigrist, S.J. Autophagy within the Mushroom Body Protects from Synapse Aging in a Non-Cell Autonomous Manner. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, G.; Ballabio, A. TFEB at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 2475–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardiello, M.; Palmieri, M.; Di Ronza, A.; Medina, D.L.; Valenza, M.; Gennarino, V.A.; Di Malta, C.; Donaudy, F.; Embrione, V.; Polishchuk, R.S.; et al. A Gene Network Regulating Lysosomal Biogenesis and Function. Science (1979) 2009, 325, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roczniak-Ferguson, A.; Petit, C.S.; Froehlich, F.; Qian, S.; Ky, J.; Angarola, B.; Walther, T.C.; Ferguson, S.M. The Transcription Factor TFEB Links MTORC1 Signaling to Transcriptional Control of Lysosome Homeostasis. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, J.A.; Chen, Y.; Gucek, M.; Puertollano, R. MTORC1 Functions as a Transcriptional Regulator of Autophagy by Preventing Nuclear Transport of TFEB. Autophagy 2012, 8, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre, C.; Zoncu, R.; Medina, D.L.; Vetrini, F.; Erdin, S.; Erdin, S.; Huynh, T.; Ferron, M.; Karsenty, G.; Vellard, M.C.; et al. A Lysosome-to-Nucleus Signalling Mechanism Senses and Regulates the Lysosome via MTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre, C.; Di Malta, C.; Polito, V.A.; Arencibia, M.G.; Vetrini, F.; Erdin, S.; Erdin, S.U.; Huynh, T.; Medina, D.; Colella, P.; et al. TFEB Links Autophagy to Lysosomal Biogenesis. Science 2011, 332, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Spina, M.; Contreras, P.S.; Rissone, A.; Meena, N.K.; Jeong, E.; Martina, J.A. MiT/TFE Family of Transcription Factors: An Evolutionary Perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 609683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, J.A.; Diab, H.I.; Lishu, L.; Jeong-A, L.; Patange, S.; Raben, N.; Puertollano, R. The Nutrient-Responsive Transcription Factor TFE3 Promotes Autophagy, Lysosomal Biogenesis, and Clearance of Cellular Debris. Sci. Signal. 2014, 7, ra9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decressac, M.; Mattsson, B.; Weikop, P.; Lundblad, M.; Jakobsson, J.; Björklund, A. TFEB-Mediated Autophagy Rescues Midbrain Dopamine Neurons from α-Synuclein Toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E1817–E1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polito, V.A.; Li, H.; Martini-Stoica, H.; Wang, B.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Swartzlander, D.B.; Palmieri, M.; di Ronza, A.; Lee, V.M.; et al. Selective Clearance of Aberrant Tau Proteins and Rescue of Neurotoxicity by Transcription Factor EB. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 1142–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Cao, H.; Zuo, C.; Huang, Y.; Miao, J.; Song, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, F. TFEB in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implications. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 173, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouché, V.; Espinosa, A.P.; Leone, L.; Sardiello, M.; Ballabio, A.; Botas, J. Drosophila Mitf Regulates the V-ATPase and the Lysosomal-Autophagic Pathway. Autophagy 2016, 12, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fábregas, J.; Prescott, A.; van Kasteren, S.; Pedrioli, D.L.; McLean, I.; Moles, A.; Reinheckel, T.; Poli, V.; Watts, C. Lysosomal Protease Deficiency or Substrate Overload Induces an Oxidative-Stress Mediated STAT3-Dependent Pathway of Lysosomal Homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, I.; van de Vlekkert, D.; Wolf, E.; Finkelstein, D.; Neale, G.; Machado, E.; Mosca, R.; Campos, Y.; Tillman, H.; Roussel, M.F.; et al. MYC Competes with MiT/TFE in Regulating Lysosomal Biogenesis and Autophagy through an Epigenetic Rheostat. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.R.; Kim, H.; Oh, S.; Lee, J.G.; Kee, M.; Ko, H.J.; Kweon, M.N.; Won, K.J.; Baek, S.H. AMPK–SKP2–CARM1 Signalling Cascade in Transcriptional Regulation of Autophagy. Nature 2016, 534, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, D.; Yang, X.; Li, M. Lysosomal Quality Control Review. Autophagy 2025, 21, 1413–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, M.; Yang, C.; Stenmark, H. Lysosomal Membrane Homeostasis and Its Importance in Physiology and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.C.; Krogsaeter, E.; Butz, E.S.; Li, Y.; Puertollano, R.; Wahl-Schott, C.; Biel, M.; Grimm, C. TRPML2 Is an Osmo/Mechanosensitive Cation Channel in Endolysosomal Organelles. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Chen, W.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; et al. Drosophila TMEM63 and Mouse TMEM63A Are Lysosomal Mechanosensory Ion Channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, M.; Schink, K.O.; Wenzel, E.M.; Nähse, V.; Bongiovanni, A.; Lafont, F.; Stenmark, H. ESCRT-mediated Lysosome Repair Precedes Lysophagy and Promotes Cell Survival. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowyra, M.L.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Naismith, T.V.; Hanson, P.I. Triggered Recruitment of ESCRT Machinery Promotes Endolysosomal Repair. Science 2018, 360, eaar5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Larsen, K.P.; Ou, C.; Rose, K.; Hurley, J.H. In Vitro Reconstitution of Calcium-Dependent Recruitment of the Human ESCRT Machinery in Lysosomal Membrane Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2205590119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Motsinger, M.M.; Li, J.; Bohannon, K.P.; Hanson, P.I. Ca2+-Sensor ALG-2 Engages ESCRTs to Enhance Lysosomal Membrane Resilience to Osmotic Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2318412121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebstrup, M.L.; Sønder, S.L.; Fogde, D.L.; Heitmann, A.S.B.; Dietrich, T.N.; Dias, C.; Jäättelä, M.; Maeda, K.; Nylandsted, J. Annexin A7 Mediates Lysosome Repair Independently of ESCRT-III. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1211498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, C.; Mangiarotti, A.; Vanhille-Campos, C.; Aylan, B.; Pellegrino, E.; Athanasiadi, N.; Fearns, A.; Rodgers, A.; Franzmann, T.M.; Šarić, A.; et al. Stress Granules Plug and Stabilize Damaged Endolysosomal Membranes. Nature 2023, 623, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.X.; Finkel, T. A Phosphoinositide Signalling Pathway Mediates Rapid Lysosomal Repair. Nature 2022, 609, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, M.; Wenzel, E.M.; Gilani, S.; Holland, L.K.; Lystad, A.H.; Phuyal, S.; Olkkonen, V.M.; Brech, A.; Jäättelä, M.; Maeda, K.; et al. Cholesterol Transfer via Endoplasmic Reticulum Contacts Mediates Lysosome Damage Repair. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e112677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xu, P.; Bentley-DeSousa, A.; Hancock-Cerutti, W.; Cai, S.; Johnson, B.T.; Tonelli, F.; Shao, L.; Talaia, G.; Alessi, D.R.; et al. The Bridge-like Lipid Transport Protein VPS13C/PARK23 Mediates ER-Lysosome Contacts Following Lysosome Damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 2025, 27, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgan, J.; Florey, O. Many Roads Lead to CASM: Diverse Stimuli of Noncanonical Autophagy Share a Unifying Molecular Mechanism. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niekamp, P.; Scharte, F.; Sokoya, T.; Vittadello, L.; Kim, Y.; Deng, Y.; Südhoff, E.; Hilderink, A.; Imlau, M.; Clarke, C.J.; et al. Ca2+-Activated Sphingomyelin Scrambling and Turnover Mediate ESCRT-Independent Lysosomal Repair. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.D.; Wang, C.; Padman, B.S.; Lazarou, M.; Youle, R.J. STING Induces LC3B Lipidation onto Single-Membrane Vesicles via the V-ATPase and ATG16L1-WD40 Domain. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e202009128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, J.M.; Walkup, W.G.; Hooper, K.; Li, T.; Kishi-Itakura, C.; Ng, A.; Lehmberg, T.; Jha, A.; Kommineni, S.; Fletcher, K.; et al. GABARAP Sequesters the FLCN-FNIP Tumor Suppressor Complex to Couple Autophagy with Lysosomal Biogenesis. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Ponpuak, M.; Mudd, M.H.; Kimura, T.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Mandell, M.; Bruun, J.A.; et al. TRIMs and Galectins Globally Cooperate and TRIM16 and Galectin-3 Co-Direct Autophagy in Endomembrane Damage Homeostasis. Dev. Cell 2016, 39, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Y.H.; Chen, L.M.W.; Yang, J.Y.; Yang, W.Y. Spatiotemporally Controlled Induction of Autophagy-Mediated Lysosome Turnover. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurston, T.L.M.; Wandel, M.P.; Von Muhlinen, N.; Foeglein, Á.; Randow, F. Galectin 8 Targets Damaged Vesicles for Autophagy to Defend Cells against Bacterial Invasion. Nature 2012, 482, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Kravic, B.; Meyer, H. Repair or Lysophagy: Dealing with Damaged Lysosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maejima, I.; Takahashi, A.; Omori, H.; Kimura, T.; Takabatake, Y.; Saitoh, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Hamasaki, M.; Noda, T.; Isaka, Y.; et al. Autophagy Sequesters Damaged Lysosomes to Control Lysosomal Biogenesis and Kidney Injury. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 2336–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, A.; Dadi, A.; Yavarow, Z.; Alfano, L.N.; Anderson, D.; Arkin, M.R.; Chou, T.F.; D’Ambrosio, E.S.; Diaz-Manera, J.; Dudley, J.P.; et al. 2024 VCP International Conference: Exploring Multi-Disciplinary Approaches from Basic Science of Valosin Containing Protein, an AAA+ ATPase Protein, to the Therapeutic Advancement for VCP-Associated Multisystem Proteinopathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 207, 106861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.M.; Wrobel, L.; Ashkenazi, A.; Fernandez-Estevez, M.; Tan, K.; Bürli, R.W.; Rubinsztein, D.C. VCP/P97 Regulates Beclin-1-Dependent Autophagy Initiation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, M.A.; Xu, H. Lysosomal Exocytosis and Lipid Storage Disorders. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentzell, M.T.; Rehbein, U.; Cadena Sandoval, M.; De Meulemeester, A.S.; Baumeister, R.; Brohée, L.; Berdel, B.; Bockwoldt, M.; Carroll, B.; Chowdhury, S.R.; et al. G3BPs Tether the TSC Complex to Lysosomes and Suppress MTORC1 Signaling. Cell 2021, 184, 655–674.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Abudu, Y.P.; Claude-Taupin, A.; Gu, Y.; Kumar, S.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Mudd, M.H.; Allers, L.; Salemi, M.; et al. Galectins Control MTOR in Response to Endomembrane Damage. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 120–135.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, R.; Richardson, C.E. Maintenance and Decline of Neuronal Lysosomal Function in Aging. Cells 2025, 14, 1976. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241976

Zhong R, Richardson CE. Maintenance and Decline of Neuronal Lysosomal Function in Aging. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1976. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241976

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Ruiling, and Claire E. Richardson. 2025. "Maintenance and Decline of Neuronal Lysosomal Function in Aging" Cells 14, no. 24: 1976. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241976

APA StyleZhong, R., & Richardson, C. E. (2025). Maintenance and Decline of Neuronal Lysosomal Function in Aging. Cells, 14(24), 1976. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241976