Psychosomatic Disorders, Epigenome, and Gut Microbiota

Highlights

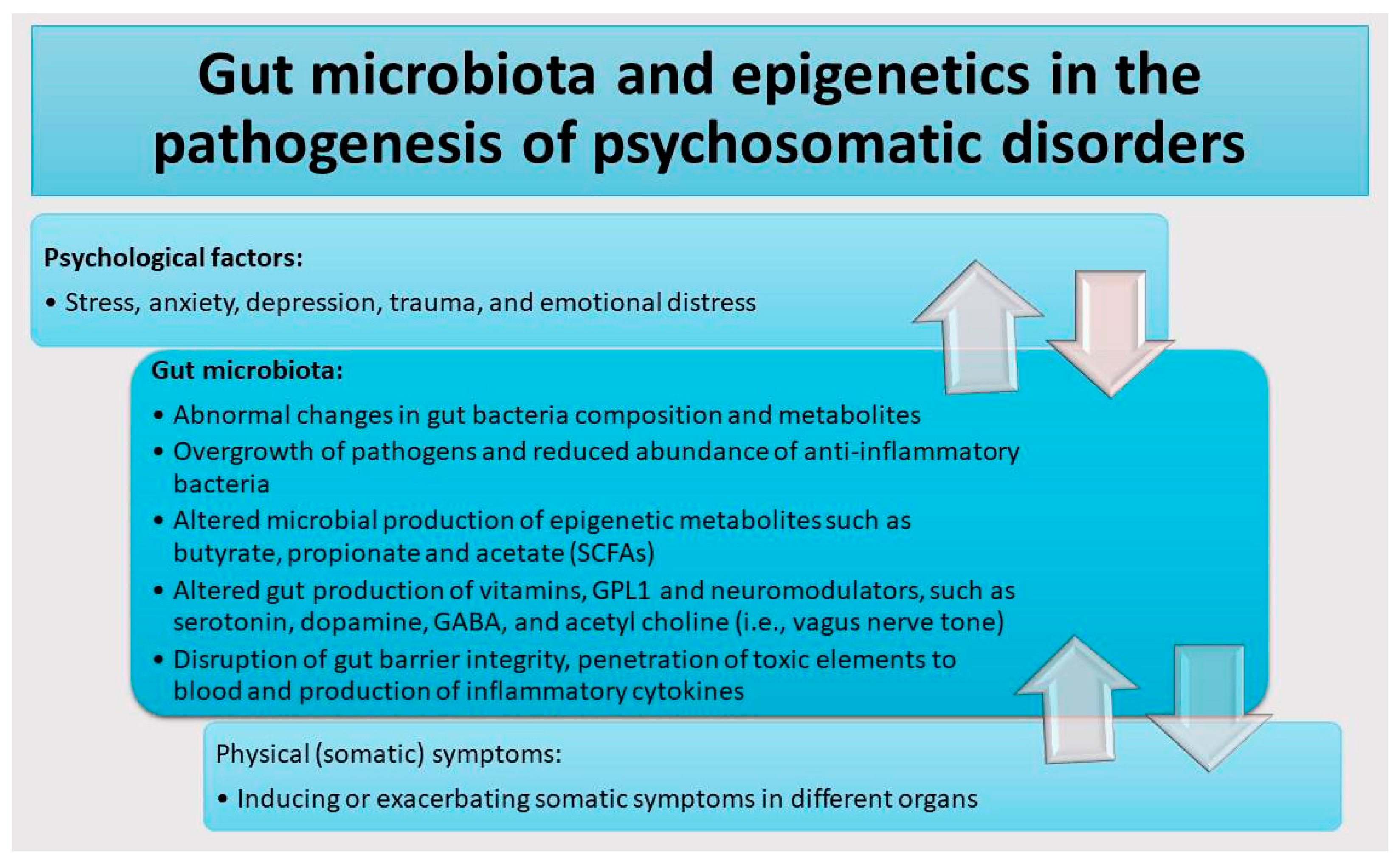

- Patients with psychosomatic disorders exhibited mental distress, gut dysbiosis, and aberrant gut microbiota (GM) profiles that contribute to the severity of disease via epigenetic mechanisms.

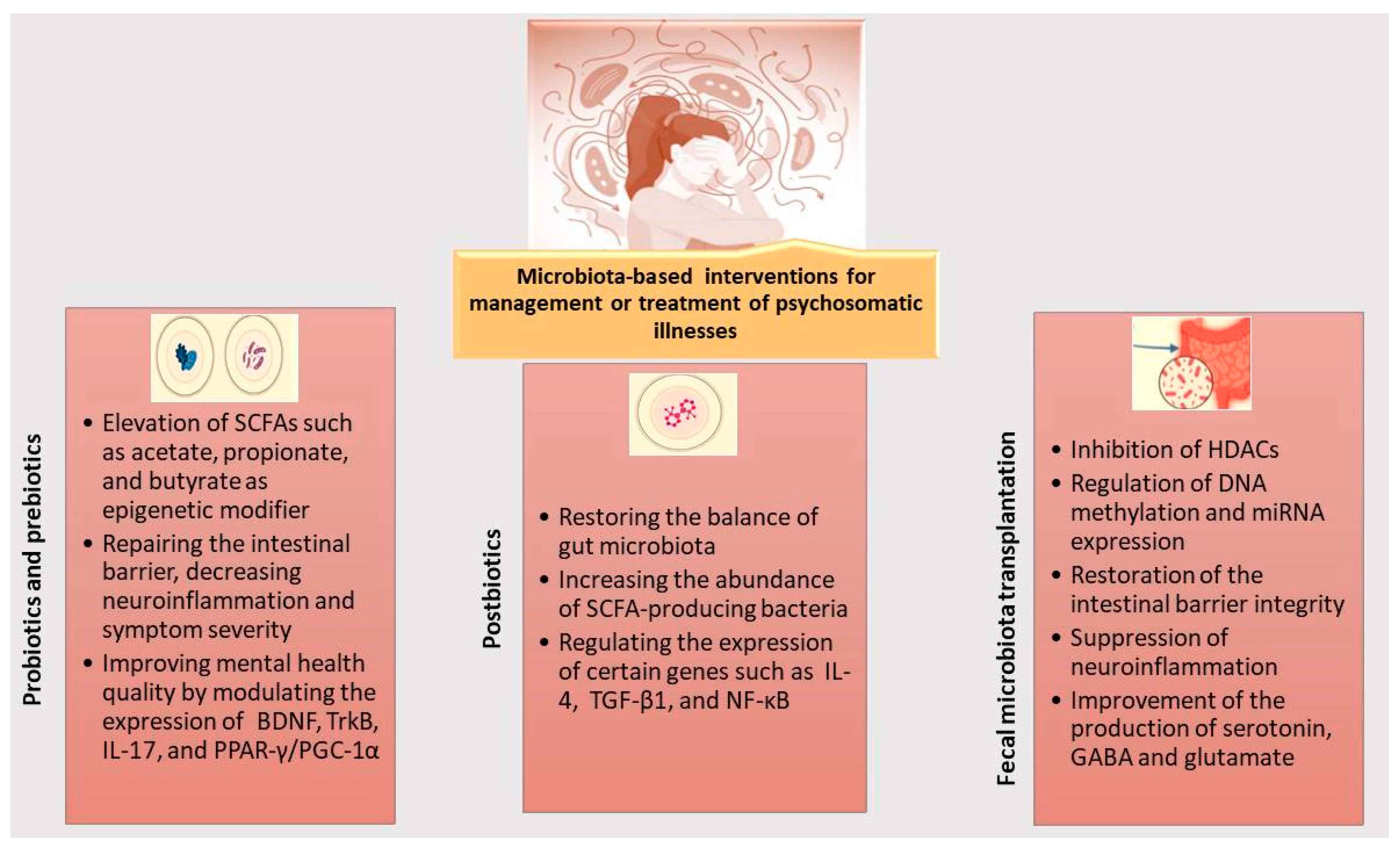

- Probiotic supplements and other gut-balancing therapies could serve as promising approaches for treating psychosomatic disorders by mitigating epigenetic aberrations.

- The intercommunication system between the gut and the brain, known as the gut–brain–microbiota axis, plays a crucial role in pathogenesis of psychosomatic disorders

- GM based interventions such as “prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation” may contribute to improving physical and psychological symptoms in patients with psychosomatic disorders by replenishing the abnormal GM composition and enhancing concentrations of beneficial epigenetic metabolites.

- Human iPSC-derived multicellular organoids may serve as powerful platforms for therapeutic interventions using probiotic supplements and for unraveling mechanistic pathways underlying inter-organ interactions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Patients with Psychosomatic Disorders

3. Epigenetic Dysregulation of Genes Related to Gut Dysbiosis and Neuronal Functions in Patients with Psychosomatic Disorders

4. Microbiota-Based Interventions Affecting Epigenome for Management or Treatment of Psychosomatic Disorders

- Prebiotics

- Probiotics

- Postbiotics

- Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)

- Electrophysical therapies to temper gut dysbiosis and inflammation and improve brain function

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sugaya, N. Work-related problems and the psychosocial characteristics of individuals with irritable bowel syndrome: An updated literature review. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2024, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, B.E.; Patel, N.K. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efremov, A. Psychosomatics: Communication of the central nervous system through connection to tissues, organs, and cells. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2024, 22, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Jain, C.K. Psychosomatic disorder: The current implications and challenges. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2024, 22, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.; Cryan, J.; Quigley, E.; Dinan, T.; Clarke, G. A sustained hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis response to acute psychosocial stress in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 3123–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demori, I.; Losacco, S.; Giordano, G.; Mucci, V.; Blanchini, F.; Burlando, B. Fibromyalgia pathogenesis explained by a neuroendocrine multistable model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Fuentes, D.; Obrero-Gaitan, E.; Zagalaz-Anula, N.; Ibanez-Vera, A.J.; Achalandabaso-Ochoa, A.; Lopez-Ruiz, M.d.C.; Rodriguez-Almagro, D.; Lomas-Vega, R. Alteration of postural balance in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passacatini, L.C.; Ilari, S.; Nucera, S.; Scarano, F.; Macrì, R.; Caminiti, R.; Serra, M.; Oppedisano, F.; Maiuolo, J.; Palma, E. Multiple Aspects of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Role of the Immune System: An Overview of Systematic Reviews with a Focus on Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedda, S.; Cadoni, M.P.L.; Medici, S.; Aiello, E.; Erre, G.L.; Nivoli, A.M.; Carru, C.; Coradduzza, D. Fibromyalgia, Depression, and Autoimmune Disorders: An Interconnected Web of Inflammation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumbi, L.; Giannelou, M.-A.; Castelli, L. The gut–brain axis in irritable bowel syndrome: Neuroendocrine and epigenetic pathways. Acad. Biol. 2025, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Yaow, C.Y.L.; Moo, J.R.; Koo, S.W.K.; Loo, E.X.L.; Siah, K.T.H. A systematic review of the association between environmental risk factors and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaper, S.J.; Stengel, A. Emotional stress responsivity of patients with IBS-a systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 153, 110694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.S.; Arsenault, J.E.; Cates, S.C.; Muth, M.K. Perceived stress, unhealthy eating behaviors, and severe obesity in low-income women. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyjeet, F.; Naz, S.; Kumar, V.; Aung, N.H.; Bansari, K.; Irfan, S.; Rizwan, A. Psychological stress as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A case-control study. Cureus 2020, 12, e10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-León, M.Á.; Pérez-Mármol, J.M.; Gonzalez-Pérez, R.; del Carmen García-Ríos, M.; Peralta-Ramírez, M.I. Relationship between resilience and stress: Perceived stress, stressful life events, HPA axis response during a stressful task and hair cortisol. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 202, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, T.; Reis, V.A.; Linke, S.E.; Greenberg, B.H.; Mills, P.J. Depression in heart failure: A meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, E.; Wu, Q.; Cai, Y. Mediating effect of depressive symptoms on the relationship of chronic pain and cardiovascular diseases among Chinese population: Evidence from the CHARLS. J. Psychosom. Res. 2024, 180, 111639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uçar, M.; Sarp, Ü.; Karaaslan, Ö.; Gül, A.I.; Tanik, N.; Arik, H.O. Health anxiety and depression in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. J. Int. Med. Res. 2015, 43, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietta, P.; Fietta, P.; Manganelli, P. Fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. Acta Biomed.-Ateneo Parm. 2007, 78, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiggia, A.; Tesio, V.; Colonna, F.; Fusaro, E.; Geminiani, G.C.; Castelli, L. Stressful Life Events and Psychosomatic Symptoms in Fibromyalgia Syndrome and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Li, Z.; Gu, X.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X. Psychosomatic Disorders in Patients with Gastrointestinal Diseases: Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study of 1186 Inpatients. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 6637084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, S.M.; Clarke, G.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Irritable bowel syndrome and stress-related psychiatric co-morbidities: Focus on early life stress. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. 2017, 239, 219–246. [Google Scholar]

- Mörkl, S.; Butler, M.I.; Holl, A.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Probiotics and the microbiota-gut-brain axis: Focus on psychiatry. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2020, 9, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Alizadeh-Tabari, S.; Zamani, V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugon, P.; Dufour, J.-C.; Colson, P.; Fournier, P.-E.; Sallah, K.; Raoult, D. A comprehensive repertoire of prokaryotic species identified in human beings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Okpara, E.S.; Hu, W.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Chiang, J.Y.; Han, S. Interactive relationships between intestinal flora and bile acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.a.; Chu, J.; Feng, S.; Guo, C.; Xue, B.; He, K.; Li, L. Immunological mechanisms of inflammatory diseases caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paciolla, C.; Manganelli, M.; Di Chiano, M.; Montenegro, F.; Gallone, A.; Sallustio, F.; Guida, G. Valeric Acid: A Gut-Derived Metabolite as a Potential Epigenetic Modulator of Neuroinflammation in the Gut–Brain Axis. Cells 2025, 14, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, D.; Nigam, P.S. Antibiotic-therapy-induced gut dysbiosis affecting gut microbiota—Brain axis and cognition: Restoration by intake of probiotics and synbiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, G.; Flores, G.A.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P. The Impact of Antibiotic Therapy on Intestinal Microbiota: Dysbiosis, Antibiotic Resistance, and Restoration Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharian, F.; Thirugnanam, S.; Welsh, D.A.; Kim, W.-K.; Rappaport, J.; Bittinger, K.; Rout, N. The role of gut dysbiosis in the loss of intestinal immune cell functions and viral pathogenesis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrncir, T. Gut microbiota dysbiosis: Triggers, consequences, diagnostic and therapeutic options. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Zhou, J.-R. Gut microbiota dysbiosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and epigenetic alterations in metabolic diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, A.E.; BinMowyna, M.N.; Raposo, A.; Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmed, F.; Otayf, A.Y.; Carrascosa, C.; Saraiva, A.; Karav, S. Beyond the gut: Unveiling butyrate’s global health impact through gut health and dysbiosis-related conditions: A narrative review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Che, X.; Briese, T.; Ranjan, A.; Allicock, O.; Yates, R.A.; Cheng, A.; March, D.; Hornig, M.; Komaroff, A.L. Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome is associated with bacterial network disturbances and fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 288–304. e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Román, A.; Pagán-Zayas, N.; Velázquez-Rivera, L.I.; Torres-Ventura, A.C.; Godoy-Vitorino, F. Insights into gut dysbiosis: Inflammatory diseases, obesity, and restoration approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrykus, M.; Czaja-Stolc, S.; Stankiewicz, M.; Kaska, Ł.; Małgorzewicz, S. Intestinal microbiota as a contributor to chronic inflammation and its potential modifications. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuda, H.; Okamoto, T.; Wada, K. Leaky gut: Effect of dietary fiber and fats on microbiome and intestinal barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paray, B.A.; Albeshr, M.F.; Jan, A.T.; Rather, I.A. Leaky gut and autoimmunity: An intricate balance in individuals health and the diseased state. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, Y.-R.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, Y.-S.; Park, H.-Y. Diet-induced gut dysbiosis and leaky gut syndrome. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelli, M.; Franza, L.; Pignataro, G.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Piccioni, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Interaction between lipopolysaccharide and gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Angelo, M.; Brandolini, L.; Catanesi, M.; Castelli, V.; Giorgio, C.; Alfonsetti, M.; Tomassetti, M.; Zippoli, M.; Benedetti, E.; Cesta, M.C. Differential effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in an in vitro model of human leaky gut. Cells 2023, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrenovich, M.E. Leaky gut, leaky brain? Microorganisms 2018, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohesara, S.; Abdolmaleky, H.M.; Thiagalingam, S.; Zhou, J.-R. Gut microbiota defined epigenomes of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases reveal novel targets for therapy. Epigenomics 2024, 16, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morena, D.; Lippi, M.; Scopetti, M.; Turillazzi, E.; Fineschi, V. Leaky gut biomarkers as predictors of depression and suicidal risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzki, L.; Maes, M. From “leaky gut” to impaired glia-neuron communication in depression. In Major Depressive Disorder: Rethinking and Understanding Recent Discoveries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Toro-Barbosa, M.; Hurtado-Romero, A.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; García-Cayuela, T. Psychobiotics: Mechanisms of action, evaluation methods and effectiveness in applications with food products. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandouzi, Z.A.; Lee, J.; del Carmen Rosas, M.; Chen, J.; Henderson, W.A.; Starkweather, A.R.; Cong, X.S. Associations of neurotransmitters and the gut microbiome with emotional distress in mixed type of irritable bowel syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracco, G.; Faimann, I.; Reichmann, F. Inflammatory bowel disease and neuropsychiatric disorders: Mechanisms and emerging therapeutics targeting the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 269, 108831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuchaai, E.; Endres, V.; Jones, B.; Shankar, S.; Klemashevich, C.; Sun, Y.; Wu, C.-S. Deletion of ghrelin alters tryptophan metabolism and exacerbates experimental ulcerative colitis in aged mice. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 1558–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaldaferri, F.; D’Onofrio, A.M.; Chiera, E.; Gomez-Nguyen, A.; Ferrajoli, G.F.; Di Vincenzo, F.; Petito, V.; Laterza, L.; Pugliese, D.; Napolitano, D. Impact of Psychopathology and Gut Microbiota on Disease Progression in Ulcerative Colitis: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, N.; Su, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, R. Gut-microbiota-derived metabolites maintain gut and systemic immune homeostasis. Cells 2023, 12, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Di Ciaula, A.; Mahdi, L.; Jaber, N.; Di Palo, D.M.; Graziani, A.; Baffy, G.; Portincasa, P. Unraveling the role of the human gut microbiome in health and diseases. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Fang, W.; Zheng, P.; Xie, S.; Jiang, X.; Luo, W.; Han, L.; Zhao, L.; Lu, L.; Zhai, L. Multi-kingdom microbiota analysis reveals bacteria-viral interplay in IBS with depression and anxiety. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Moloney, G.M.; Keane, L.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. The gut microbiota-immune-brain axis: Therapeutic implications. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.K.; Oh, J.S. Interaction of the Vagus Nerve and Serotonin in the Gut–Brain Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S. Enteric nervous system alterations in inflammatory bowel disease: Perspectives and implications. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Zamora, A.; Rábago-Monzón, Á.R.; Armienta-Rojas, D.A.; Camberos-Barraza, J.; De la Herrán-Arita, A.K. The gut–brain axis: Collective impact of psychosomatic conditions and gut microbiota on health and disease. J. Clin. Basic Psychosom. 2025, 3, 025040008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, I.A.; Bianchi-Smak, J.; Laubitz, D.; Schiro, G.; Midura-Kiela, M.T.; Besselsen, D.G.; Vedantam, G.; Jarmakiewicz, S.; Filip, R.; Ghishan, F.K. Transplant of microbiota from Crohn’s disease patients to germ-free mice results in colitis. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2333483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-M.; Kim, J.-K.; Joo, M.-K.; Shin, Y.-J.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, D.-H. Transplantation of fecal microbiota from patients with inflammatory bowel disease and depression alters immune response and behavior in recipient mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Scholz, M.; Lomer, M.C.; Ralph, F.S.; Irving, P.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.; Whelan, K. Gut microbiota associations with diet in irritable bowel syndrome and the effect of low FODMAP diet and probiotics. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginean, C.M.; Popescu, M.; Drocas, A.I.; Cazacu, S.M.; Mitrut, R.; Marginean, I.C.; Iacob, G.A.; Popescu, M.S.; Docea, A.O.; Mitrut, P. Gut–Brain Axis, Microbiota and Probiotics—Current Knowledge on Their Role in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Review. Gastrointest. Disord. 2023, 5, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mönnikes, H.; Tebbe, J.; Hildebrandt, M.; Arck, P.; Osmanoglou, E.; Rose, M.; Klapp, B.; Wiedenmann, B.; Heymann-Mönnikes, I. Role of stress in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Evidence for stress-induced alterations in gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity. Dig. Dis. 2001, 19, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.-Y.; Cheng, C.-W.; Tang, X.-D.; Bian, Z.-X. Impact of psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, G.; Keating, D.J.; Young, R.L.; Wong, M.-L.; Licinio, J.; Wesselingh, S. From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: Mechanisms and pathways. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.-K.; Kim, D.H. Lactobacillus mucosae and Bifidobacterium longum synergistically alleviate immobilization stress-induced anxiety/depression in mice by suppressing gut dysbiosis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsalata, M.; Prospero, L.; Ignazzi, A.; Riezzo, G.; D’Attoma, B.; Mallardi, D.; Goscilo, F.; Notarnicola, M.; De Nunzio, V.; Pinto, G. Depression in Diarrhea-Predominant IBS Patients: Exploring the Link Between Gut Barrier Dysfunction and Erythrocyte Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Levels. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, J.; Fournier, C.; Durdevic, M.; Knoblich, L.; Keip, B.; Dejaco, C.; Trauner, M.; Moser, G. A microbial signature of psychological distress in irritable bowel syndrome. Biopsychosoc. Sci. Med. 2018, 80, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.J.; Tong, T.; Chew, J.; Lim, W.L. Antidepressive mechanisms of probiotics and their therapeutic potential. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simrén, M.; Barbara, G.; Flint, H.J.; Spiegel, B.M.; Spiller, R.C.; Vanner, S.; Verdu, E.F.; Whorwell, P.J.; Zoetendal, E.G. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: A Rome foundation report. Gut 2013, 62, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, B.; Duan, Z.; Xia, Z.; Ding, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Yang, B.; Wang, X. Depression and anxiety in patients with active ulcerative colitis: Crosstalk of gut microbiota, metabolomics and proteomics. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1987779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Deng, M.; Shen, Z.; Nie, K.; Luo, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, K.; Chen, X. Bacteroides vulgatus alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis and depression-like behaviour by facilitating gut-brain axis balance. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1287271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhu, N.T.; Chen, D.Y.-T.; Yang, Y.-C.S.; Lo, Y.-C.; Kang, J.-H. Associations between brain-gut Axis and psychological distress in fibromyalgia: A microbiota and magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Pain 2024, 25, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clos-Garcia, M.; Andrés-Marin, N.; Fernández-Eulate, G.; Abecia, L.; Lavín, J.L.; van Liempd, S.; Cabrera, D.; Royo, F.; Valero, A.; Errazquin, N. Gut microbiome and serum metabolome analyses identify molecular biomarkers and altered glutamate metabolism in fibromyalgia. EBioMedicine 2019, 46, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, G.-T.; Kang, J. Microbial composition and stool short chain fatty acid levels in fibromyalgia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittayanon, R.; Lau, J.T.; Yuan, Y.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Tse, F.; Surette, M.; Moayyedi, P. Gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome—A systematic review. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Yin, S.; Xiao, F.; Gong, C.; Zhou, J.; Liu, K.; Cheng, Y. Changes in short-chain fatty acids affect brain development in mice with early life antibiotic-induced dysbacteriosis. Transl. Pediatr. 2024, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xie, P.; He, C.; Li, Q.; Yao, X.; Mao, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, T. Epigenetic modifications and emerging therapeutic targets in cardiovascular aging and diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 211, 107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- la Torre, A.; Lo Vecchio, F.; Greco, A. Epigenetic mechanisms of aging and aging-associated diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Sheng, H.; Hu, C.; Li, F.; Cai, B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y. Effects of DNA methylation on gene expression and phenotypic traits in cattle: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahurkar-Joshi, S.; Thompson, M.; Villarruel, E.; Lewis, J.D.; Lin, L.D.; Farid, M.; Nayeb-Hashemi, H.; Storage, T.; Weiss, G.A.; Limketkai, B.N. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Identifies Potential Disease-Specific Biomarkers and Pathophysiologic Mechanisms in Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Celiac Disease. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2025, 37, e14980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahurkar, S.; Polytarchou, C.; Iliopoulos, D.; Pothoulakis, C.; Mayer, E.A.; Chang, L. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Zhang, H.; Xue, S.-M.; Li, G.; Cheng, H.-Y.M.; Cao, J.-M. Contribution of DNA methylation in chronic stress–induced cardiac remodeling and arrhythmias in mice. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 12240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerra, M.C.; Carnevali, D.; Pedersen, I.S.; Donnini, C.; Manfredini, M.; González-Villar, A.; Triñanes, Y.; Pidal-Miranda, M.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Carrillo-De-La-Peña, M.T. DNA methylation changes in genes involved in inflammation and depression in fibromyalgia: A pilot study. Scand. J. Pain 2021, 21, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polli, A.; Ghosh, M.; Bakusic, J.; Ickmans, K.; Monteyne, D.; Velkeniers, B.; Bekaert, B.; Godderis, L.; Nijs, J. DNA methylation and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression account for symptoms and widespread hyperalgesia in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and comorbid fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 1936–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, T.; Shibata, T.; Okubo, M.; Sumi, K.; Ishizuka, T.; Nakamura, M.; Nagasaka, M.; Nakagawa, Y.; Ohmiya, N.; Arisawa, T. Change in DNA methylation patterns of SLC6A4 gene in the gastric mucosa in functional dyspepsia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, B.R.; Overstreet, D.S.; Penn, T.M.; Bakshi, R.; Quinn, T.L.; Sims, A.; Ptacek, T.; Jackson, P.; Long, D.L.; Aroke, E.N. Epigenome-wide DNA methylation profiling of conditioned pain modulation in individuals with non-specific chronic low back pain. Clin. Epigenet. 2022, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, J.; Rhein, M.; Gombert, S.; Meyer-Bockenkamp, F.; Buhck, M.; Eberhardt, M.; Leffler, A.; Frieling, H.; Karst, M. Childhood traumatization is associated with differences in TRPA1 promoter methylation in female patients with multisomatoform disorder with pain as the leading bodily symptom. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Gudiel, H.; Peralta, V.; Deuschle, M.; Navarro, V.; Fañanás, L. Epigenetics-by-sex interaction for somatization conferred by methylation at the promoter region of SLC6A4 gene. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 89, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, J.; Rhein, M.; Glahn, A.; Frieling, H.; Karst, M. Leptin promoter methylation in female patients with painful multisomatoform disorder and chronic widespread pain. Clin. Epigenet. 2022, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, K.; Kantake, M.; Tanaka, K.; Nakaoka, H.; Shimizu, T.; Shoji, H. Methylation of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene in Children with Somatic Symptom Disorder: A Case-Control Study. Epigenomes 2025, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.A.; Johnson, K.; Hodgkinson, C.; Goldman, D.; Hallett, M. Methylome changes associated with functional movement/conversion disorder: Influence of biological sex and childhood abuse exposure. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 125, 110756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, E.J.; Peña, C.J.; Kundakovic, M.; Mitchell, A.; Akbarian, S. Epigenetic basis of mental illness. Neuroscientist 2016, 22, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Shi, X.; Tang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Gao, G.; Lin, C.; Chen, A. Contribution of amygdala histone acetylation in early life stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity and emotional comorbidity. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 843396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Pan, C.; Cai, Q.; Zhao, Y.; He, D.; Wei, W.; Zhang, N.; Shi, S.; Chu, X.; Zhang, F. Assessing the effect of interaction between gut microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease on the risks of depression. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2022, 26, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.; Kotliar, M.; Woo, V.; Jagannathan, S.; Whitt, J.; Moncivaiz, J.; Aronow, B.J.; Dubinsky, M.C.; Hyams, J.S.; Markowitz, J.F. Microbiota-sensitive epigenetic signature predicts inflammation in Crohn’s disease. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e122104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, F.J.; Ahern, A.; Fitzgerald, R.; Laserna-Mendieta, E.; Power, E.; Clooney, A.; O’donoghue, K.; McMurdie, P.; Iwai, S.; Crits-Christoph, A. Colonic microbiota is associated with inflammation and host epigenomic alterations in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, V.; Lyon, D.E.; Archer, K.J.; Zhou, Q.; Brumelle, J.; Jones, K.H.; Gao, G.; York, T.P.; Jackson-Cook, C. Epigenetic alterations and an increased frequency of micronuclei in women with fibromyalgia. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2013, 2013, 795784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, I.-C.; Dobre, M.; Milanesi, E.; Manuc, T. Crosstalk between Anxiety and Depression and Inflammatory bowel diseases: Preliminary data on circulating miRNAs. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67, S71–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, M.; Manuc, T.E.; Manuc, M.; Matei, I.-C.; Dobre, A.-M.; Dragne, A.-D.; Maffioletti, E.; Pelisenco, I.A.; Milanesi, E. Circulating miRNA Profile in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Fathy, W.; Abdelaleem, E.A.; Nasser, M.; Yehia, A.; Elanwar, R. The impact of micro RNA-320a serum level on severity of symptoms and cerebral processing of pain in patients with fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, K.; Gassner, K.; Lang, M.; Ozelyte, J.; Hausmann, B.; Crepaz, D.; Pjevac, P.; Gasche, C.; Berry, D.; Vesely, C. Human-derived microRNA 21 regulates indole and L-tryptophan biosynthesis transcripts in the gut commensal Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. mBio 2025, 16, e03928-03924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.; Brabyn, S.; Ratcliff, J.; Varley, D.; Allgar, V.; Gilbody, S.; Clarke, C.; Lagos, D. Assessment of cytokines, microRNA and patient related outcome measures in conversion disorder/functional neurological disorder (CD/FND): The CANDO clinical feasibility study. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2021, 13, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-G.; Rao, Y.-F.; Jiang, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, S.-M. MicroRNA-155-5p inhibition alleviates irritable bowel syndrome by increasing claudin-1 and ZO-1 expression. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfarth, C.; Schmitteckert, S.; Härtle, J.D.; Houghton, L.A.; Dweep, H.; Fortea, M.; Assadi, G.; Braun, A.; Mederer, T.; Pöhner, S. miR-16 and miR-103 impact 5-HT4 receptor signalling and correlate with symptom profile in irritable bowel syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Zhao, P.; Li, F.; Bao, H.; Ding, S.; Ji, L.; Yan, J. MicroRNA-16 inhibits the TLR4/NF-κB pathway and maintains tight junction integrity in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olyaiee, A.; Yadegar, A.; Mirsamadi, E.S.; Sadeghi, A.; Mirjalali, H. Profiling of the fecal microbiota and circulating microRNA-16 in IBS subjects with Blastocystis infection: A case–control study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, N.H.; Peace, R.M.; Abey, S.K.; Sherwin, L.B.; Rahim-Williams, B.; Smyser, P.A.; Wiley, J.W.; Henderson, W.A. Elevated circulating miR-150 and miR-342-3p in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2014, 96, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algieri, F.; Garrido-Mesa, J.; Vezza, T.; Rodriguez-Sojo, M.J.; Rodriguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Olivares, M.; García, F.; Gálvez, J.; Morón, R.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A. Intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in DNBS-colitis via modulation of gut microbiota and microRNAs. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2537–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahurkar-Joshi, S.; Rankin, C.R.; Videlock, E.J.; Soroosh, A.; Verma, A.; Khandadash, A.; Iliopoulos, D.; Pothoulakis, C.; Mayer, E.A.; Chang, L. The colonic mucosal MicroRNAs, MicroRNA-219a-5p, and MicroRNA-338-3p are downregulated in irritable bowel syndrome and are associated with barrier function and MAPK signaling. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2409–2422. e2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Lu, G.; Chen, L.; Geng, H.; Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Yuan, M.; Sun, J.; Pei, L. Regulation of serum microRNA expression by acupuncture in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Acupunct. Med. 2022, 40, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Du, F.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y. Exploring the clinical significance of miR-148 expression variations in distinct subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2024, 88, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.-L.; Liang, G.-Q.; Chen, S.-B.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Gu, D.; Kang, L.; Liu, C. MicroRNA profiling reveals novel biomarkers for cardiovascular and psychological health in plateau psycho CVD. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaslan, E.; Güvener, O.; Görür, A.; Çelikcan, D.H.; Tamer, L.; Biçer, A. The plasma microRNA levels and their relationship with the general health and functional status in female patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arch. Rheumatol. 2021, 36, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasulova, K.; Dilek, B.; Kavak, D.E.; Pehlivan, M.; Kizildag, S. Mitochondrial miRNAs and fibromyalgia: New biomarker candidates. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, P.A.; Fraher, M.H.; Quigley, E.M. Irritable bowel syndrome: The role of food in pathogenesis and management. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 10, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K.; Zhang, M.; Tu, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wan, S.; Li, D.; Qian, Q.; Xia, L. From gut inflammation to psychiatric comorbidity: Mechanisms and therapies for anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 22, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. An update on prebiotics and on their health effects. Foods 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Jung, S.-C.; Kwak, K.; Kim, J.-S. The role of prebiotics in modulating gut microbiota: Implications for human health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohesara, S.; Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Pirani, A.; Pettinato, G.; Thiagalingam, S. The Obesity–Epigenetics–Microbiome Axis: Strategies for Therapeutic Intervention. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, M.; Moya, P.R.; Gallorio, S.; Ríos, U.; Arancibia, M. Effects of dietary fiber, phenolic compounds, and fatty acids on mental health: Possible interactions with genetic and epigenetic aspects. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Transcriptomic analysis and experiment to verify the mechanism of Xiaoyao san in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with depression. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 347, 119732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, L.; Wu, Y.; Shu, Q.; Xiong, W. The pharmacological mechanism of Xiaoyaosan polysaccharide reveals improvement of CUMS-induced depression-like behavior by carbon source-triggered butyrate-producing bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Ren, B.; Tan, X. Dietary inulin alleviated constipation induced depression and anxiety-like behaviors: Involvement of gut microbiota and microbial metabolite short-chain fatty acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhang, R.; Sun, T.; Jiang, W.; Hu, N.; Yang, P.; Luo, L.; Ren, J. Costunolide ameliorates intestinal dysfunction and depressive behaviour in mice with stress-induced irritable bowel syndrome via colonic mast cell activation and central 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 4142–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, S.; Pagliai, G.; Dinu, M.; Di Gloria, L.; Nannini, G.; Curini, L.; Pallecchi, M.; Russo, E.; Niccolai, E.; Danza, G. Effect of ancient Khorasan wheat on gut microbiota, inflammation, and short-chain fatty acid production in patients with fibromyalgia. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbek, A.; Wojtala, M.; Pirola, L.; Balcerczyk, A. Modulation of cellular biochemistry, epigenetics and metabolomics by ketone bodies. Implications of the ketogenic diet in the physiology of the organism and pathological states. Nutrients 2020, 12, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohesara, S.; Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Pirani, A.; Thiagalingam, S. Therapeutic Horizons: Gut Microbiome, Neuroinflammation, and Epigenetics in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cells 2025, 14, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Yan, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhu, Y.; He, J.; Gao, R.; Kalady, M.F.; Goel, A.; Qin, H. Ketogenic diet alleviates colitis by reduction of colonic group 3 innate lymphoid cells through altering gut microbiome. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, A.; Chimienti, G.; Notarnicola, M.; Russo, F. The ketogenic diet improves gut–brain axis in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome: Impact on 5-HT and BDNF systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimienti, G.; Orlando, A.; Lezza, A.M.S.; D’Attoma, B.; Notarnicola, M.; Gigante, I.; Pesce, V.; Russo, F. The ketogenic diet reduces the harmful effects of stress on gut mitochondrial biogenesis in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwioździk, W.; Helisz, P.; Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K. Psychobiotics as an intervention in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didari, T.; Mozaffari, S.; Nikfar, S.; Abdollahi, M. Effectiveness of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Updated systematic review with meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2015, 21, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Wang, J.; Guo, B.; Zhang, W. Effects of short-chain fatty acid-producing probiotic metabolites on symptom relief and intestinal barrier function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1616066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayuk, G.S.; Gyawali, C.P. Irritable bowel syndrome: Modern concepts and management options. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Hou, Z.; Liu, F. MiR-144 increases intestinal permeability in IBS-D rats by targeting OCLN and ZO1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 44, 2256–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zeng, Y.; Zhong, J.; Hu, Y.; Xiong, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, L. Probiotics exert gut immunomodulatory effects by regulating the expression of host miRNAs. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Liu, F. Lactobacillus casei LC01 regulates intestinal epithelial permeability through miR-144 targeting of OCLN and ZO1. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Lomer, M.C.; Farquharson, F.M.; Louis, P.; Fava, F.; Franciosi, E.; Scholz, M.; Tuohy, K.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Irving, P.M. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and a probiotic restores bifidobacterium species: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, D.; Murphy, E.F.; Tan, H.T.T.; Larsen, I.S.; O’Neill, I.; Quigley, E.M. Interactions between symptoms and psychological status in irritable bowel syndrome: An exploratory study of the impact of a probiotic combination. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2023, 35, e14477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustaoğlu, T.; Tek, N.A.; Yıldırım, A.E. Evaluation of the effects of the FODMAP diet and probiotics on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms, quality of life and depression in women with IBS. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 37, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.-P.; Cominetti, O.; Berger, B.; Combremont, S.; Marquis, J.; Xie, G.; Jia, W.; Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Bercik, P.; Bergonzelli, G. Metabolome-associated psychological comorbidities improvement in irritable bowel syndrome patients receiving a probiotic. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2347715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullish, B.; Michael, D.; Dabcheva, M.; Webberley, T.; Coates, N.; John, D.; Wang, D.; Luo, Y.; Plummer, S.; Marchesi, J. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study assessing the impact of probiotic supplementation on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in females. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 36, e14751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkawi, M.; Raja Ali, R.A.; Abdul Wahab, N.; Abdul Rathi, N.D.; Mokhtar, N.M. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial on Lactobacillus-containing cultured milk drink as adjuvant therapy for depression in irritable bowel syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan Çİn, N.N.; Açik, M.; Tertemİz, O.F.; Aktan, Ç.; Akçali, D.T.; Çakiroğlu, F.P.; Özçelİk, A.Ö. Effect of prebiotic and probiotic supplementation on reduced pain in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Psychol. Health Med. 2024, 29, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, V.H.; Hoang, L.B.; Trinh, T.O.; Tran, T.T.T.; Dao, V.L. Psychobiotics for patients with chronic gastrointestinal disorders having anxiety or depression symptoms. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Luo, C.; Zhang, H.; Xu, T. Effectiveness of Psychobiotic Bifidobacterium breve BB05 in Managing Psychosomatic Diarrhea in College Students by Regulating Gut Microbiota: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żółkiewicz, J.; Marzec, A.; Ruszczyński, M.; Feleszko, W. Postbiotics—A step beyond pre-and probiotics. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G.; Sanders, M.E.; Salminen, S. The concept of postbiotics. Foods 2022, 11, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrząb, R.; Graczyk, D.; Siedlecki, P. Molecular and cellular mechanisms influenced by postbiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Rasmusson, A.J.; Just, D.; Jayarathna, S.; Moazzami, A.; Novicic, Z.K.; Cunningham, J.L. Fecal short-chain fatty acid ratios as related to gastrointestinal and depressive symptoms in young adults. Biopsychosoc. Sci. Med. 2021, 83, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Basak, U.; Naghibi, M.; Vijayakumar, V.; Parihar, R.; Patel, J.; Jadon, P.; Pandit, A.; Dargad, R.; Khanna, S. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of live Bifidobacterium longum CECT 7347 (ES1) and heat-treated Bifidobacterium longum CECT 7347 (HT-ES1) in participants with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2338322. [Google Scholar]

- Firoozi, D.; Masoumi, S.J.; Mohammad-Kazem Hosseini Asl, S.; Fararouei, M.; Jamshidi, S. Effects of Short Chain Fatty Acid-Butyrate Supplementation on the Disease Severity, Inflammation, and Psychological Factors in Patients With Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 2025, 3165876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, D.; Masoumi, S.J.; Mohammad-Kazem Hosseini Asl, S.; Labbe, A.; Razeghian-Jahromi, I.; Fararouei, M.; Lankarani, K.B.; Dara, M. Effects of short-chain fatty acid-butyrate supplementation on expression of circadian-clock genes, sleep quality, and inflammation in patients with active ulcerative colitis: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, A.K.; Gomes, H.M.; Fröhlich, N.T.; Possa, L.; Santos, L.; Kessler, F.; Martins, A.; Rodrigues, M.S.; De Oliveira, J.; do Nascimento, N.D. Sodium butyrate protects against intestinal oxidative damage and neuroinflammation in the prefrontal cortex of ulcerative colitis mice model. Immunol. Investig. 2023, 52, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Cheng, X.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.; Guo, F.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W. Effects of lacidophilin in a mouse model of low-grade colitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhan, Y.; Cheng, X.; Tan, M.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, W. Lacidophilin tablets relieve irritable bowel syndrome in rats by regulating gut microbiota dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elmaaboud, M.A.; Awad, M.M.; El-Shaer, R.A.; Kabel, A.M. The immunomodulatory effects of ethosuximide and sodium butyrate on experimentally induced fibromyalgia: The interaction between IL-4, synaptophysin, and TGF-β1/NF-κB signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 118, 110061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikou, E.; Koliaki, C.; Makrilakis, K. The role of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in the management of metabolic diseases in humans: A narrative review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Borjihan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Wang, D.; Bai, L.; Zhu, S.; Chen, Y. Complex Probiotics Ameliorate Fecal Microbiota Transplantation-Induced IBS in Mice via Gut Microbiota and Metabolite Modulation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Salhy, M.; Winkel, R.; Casen, C.; Hausken, T.; Gilja, O.H.; Hatlebakk, J.G. Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome at 3 years after transplantation. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 982–994.e914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzawi, T.; Hausken, T.; Refsnes, P.F.; Hatlebakk, J.G.; Lied, G.A. The effect of anaerobically cultivated human intestinal microbiota compared to fecal microbiota transplantation on gut microbiota profile and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Guo, Q.; Wen, Z.; Tan, S.; Chen, J.; Lin, L.; Chen, P.; He, J.; Wen, J.; Chen, Y. The multiple effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) patients with anxiety and depression behaviors. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, W.; Su, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, X.; Yang, Y. Fecal microbiota transplantation improves clinical symptoms of fibromyalgia: An open-label, randomized, nonplacebo-controlled study. J. Pain 2024, 25, 104535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, J.; Duan, Z. Electroacupuncture Attenuates Intestinal Barrier Disruption via the α7nAChR-Mediated HO-1/p38 MAPK/NF-κB Pathway in a Mouse Model of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized, Single-Blind, Controlled Trial. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Sclocco, R.; Sharma, A.; Guerrero-López, I.; Kuo, B. Electroceuticals and magnetoceuticals in gastroenterology. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.H.; Li, J.-J.; Tang, Y. Peripheral and spinal mechanisms involved in electro-acupuncture therapy for visceral hypersensitivity. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 696843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrick, A.; Pillon, N.J.; Nilsson, E.; Lindgren, E.; Krook, A.; Ling, C.; Stener-Victorin, E. Electroacupuncture mimics exercise-induced changes in skeletal muscle gene expression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 2027–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Jiang, H.; Kong, N.; Lin, J.; Zhang, F.; Mai, T.; Cao, Z.; Xu, M. Electroacupuncture attenuated anxiety and depression-like behavior via inhibition of hippocampal inflammatory response and metabolic disorders in TNBS-induced IBD rats. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8295580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaklai, K.; Kunasol, C.; Suparan, K.; Apaijai, N.; Chitapanarux, T.; Pattanakuhar, S.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Electroacupuncture alleviates symptoms and identifies a potential microbial biomarker in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 16, 109046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Luo, F.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S. Electroacupuncture restores intestinal mucosal barrier in IBS-D rats by modulating mast cell-derived exosomal MiR-149-5p. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1641484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, G.; Atkinson, S.N.; Pan, A.; Sood, M.; Salzman, N.; Karrento, K. Impact of auricular percutaneous electrical nerve field stimulation on gut microbiome in adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome: A pilot study. J. Dig. Dis. 2023, 24, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.F.; Denson, L.A.; Haslam, D.B.; Hommel, K.A.; Ollberding, N.J.; Sahay, R.; Santucci, N.R. The microbiome in adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome and changes with percutaneous electrical nerve field stimulation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2023, 35, e14573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, J.S.; Silva, A.C.A.d.; Santos, B.L.B.d.; Reinaldo, T.S.; Oliveira, A.M.d.; Lima, R.S.P.; Torres-Leal, F.L.; Santos, A.A.d.; Silva, M.T.B.d. Physical exercise as a therapeutic approach in Gastrointestinal diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Liu, C. Effects of physical exercise on the microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.-C.; Huang, J.-C.; Young, S.-L.; Wu, C.-L.; Shih, J.-C.; Liao, L.-D.; Cheng, B. Interplay of yoga, physical activity, and probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome management: A double-blind randomized study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2024, 57, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiczy, J.; Zilbauer, M. Intestinal epithelial organoids as tools to study epigenetics in gut health and disease. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 7242415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadipour, M.; Arnauts, K.; Clarysse, M.; Thijs, T.; Liszt, K.; Van der Schueren, B.; Ceulemans, L.J.; Deleus, E.; Lannoo, M.; Ferrante, M. SCFAs switch stem cell fate through HDAC inhibition to improve barrier integrity in 3D intestinal organoids from patients with obesity. Iscience 2023, 26, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, M.; Eylem, C.C.; Erdogan-Gover, K.; Aytar-Celik, P.; Enuh, B.M.; Emregul, E.; Cabuk, A.; Yildirim, Y.; Nemutlu, E.; Muotri, A.R. Pathogenic microbiota disrupts the intact structure of cerebral organoids by altering energy metabolism. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, J.-Y.; Yang, C.-F.; Ding, J.; Chan, Y.-S. A decade of liver organoids: Advances in disease modeling. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinato, G.; Perelman, L.T.; Fisher, R.A. The development of stem cell therapies to treat diabetes utilizing the latest science and medicine have to offer. In Pancreas and Beta Cell Replacement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Casamitjana, J.; Espinet, E.; Rovira, M. Pancreatic organoids for regenerative medicine and cancer research. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 886153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Psychosomatic Disorders | Candidate Gene(s)/Targeted Pathway | Sample/Number of Participations | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multisomatoform disorder (MSD) | TRPA1/pain pathway (mechanical pain sensitivities) | Blood/151 patients and 149 matched healthy controls | Higher methylation is linked to higher pain thresholds; childhood trauma affects TRPA1 promoter methylation | [90] |

| Somatoform disorder (somatization) | SLC6A4 gene/serotonergic pathways involved in mood and behavior regulation | Peripheral blood/148 monozygotic twin subjects | DNA methylation SLC6A4 of correlates with somatization symptoms; higher methylation in women vs. men | [91] |

| Functional dyspepsia | SLC6A4 gene/serotonergic pathways | Endoscopic gastric biopsies/79 patients vs. 78 controls | Lower SLC6A4 promoter methylation in patients (p = 0.04) | [88] |

| MSD | Leptin/hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and pain pathway | Blood/151 patients and 149 matched healthy controls | Hypomethylation in female patients (CpG C-289) vs. controls (p < 0.05) | [92] |

| Somatic symptom disorder (SSD) | NR3C1/HPA axis | Saliva/34 children with SSD and 29 age- and sex-matched controls | Age-related differences in NR3C1 methylation (p < 0.05); exon 1F higher methylation in children aged 13 or older; methylation correlates with psychological symptoms in children under 13 | [93] |

| Functional movement/conversion disorder (FMD) | Genes of antigen presentation pathway and GABA receptor signaling/pathways implicated in chronic stress and pain | Peripheral blood/57 patients with FMD and 47 healthy controls | Functional motor symptoms are linked to genome-wide DNA methylation variation; association between childhood abuse in females and distinct epigenetic signatures | [94] |

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | Certain genes such as SSPO and GSTM5/glutathione metabolism and oxidative stress | Blood cells (PBMCs)/27 IBS and 23 age- and sex-matched controls | 133 differentially methylated positions of genes linked to glutathione metabolism and oxidative stress (e.g., SSPO and GSTM5) (p < 0.05) | [84] |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome and comorbid fibromyalgia | BDNF/BDNF signaling pathway | Blood/28 patients and 26 matched controls | Lower BDNF DNA methylation in exon 9 (p = 0.009) | [87] |

|

Psychosomatic

Disorders | miRNAs Analyzed | Samples/Targeted Pathway | Main Finding in Patients | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | miR-150 and miR-342-3p/AKT2 | Whole-blood samples/inflammatory and pain pathways | Up-regulation of miR-150 and miR-342-3p in IBS is involved in inflammatory pathways, colonic motility, smooth muscle function, and pain signaling (p < 0.05) | [110] |

| IBS | miR-16 and miR-103 | Jejunum/serotonergic pathways involved in mood and behavior regulation | Down-regulation of miR-16 and miR-103 and hence dysregulation of HTR4 gene (p < 0.05) | [107] |

| IBS | miRNA-219a-5p and miRNA-338-3p | Sigmoid colon/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway involved in immune response | Down-regulation of miRNA-219a-5p dysregulates proteasome/barrier function genes and increases intestinal epithelial cells permeability; down-regulation of miRNA-338-3p affects expression of MAPK-signaling genes (p = 0.026 and p = 0.004) | [112] |

| IBS | miR-16 | Serum/inflammatory pathway | miR-16 targets TLR4 and inhibits TLR4/NF-κB signaling and lncRNA XIST, improving enterocyte viability and tight junction integrity, reducing apoptosis and cytokine production (p < 0.05) | [108] |

| IBS | Analysis of eight miRNAs following TaqMan low-density array screening | Serum/multiple pathways, such as TGF-β, p53, insulin, B-cell receptors, GnRH, and adipocytokine | Up-regulation of several miRNAs (miR-1305, miR-575, miR-149-5p, miR-190a-5p, miR-135a-5p, and miR-148a-3p) and down-regulation of some others (miR-194-5p, miR-127-5p) are linked to IBS pathogenesis (p < 0.05) | [113] |

| IBS | miR-155-5p | Human (and mouse) colon samples/pathways linked to intestinal inflammation and epithelial barrier | Up-regulation of miR-155-5p (p < 0.01) and reduced levels of tight junction proteins, including CLDN1 and ZO-1 | [106] |

| IBS | miR-148 | Fasting venous blood | Association between miR-148 expression and the severity of IBS (p < 0.05) | [114] |

| Conversion disorder/functional neurological disorder | miR-146a, miR-155, miR-21 and miR-132 | Blood/inflammatory pathway | TNFA level is linked to inflammation-related miRNA expression (miR-146a and miR-155); miR-21 and miR-132 levels are linked to vascular inflammation | [105] |

| Psychological cardiovascular diseases | hsa-miR-1976 and hsa-miR-4685-3p | Fasting venous blood/neurotrophins pathways | Reduced miRNA expression targeting PI3K-Akt and neurotrophins pathways linked to cardiovascular and mental health (p < 0.05) | [115] |

| Fibromyalgia syndrome | Eleven miRNAs | Plasma | SF-36 mental symptoms directly correlate miR-142-3p and inversely with miR-320a and b (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01) | [116] |

| Fibromyalgia syndrome | MitomiR-145-5p | PBMCs/oxidative stress | Elevated mitomiR-145-5p in fibromyalgia and depression vs. controls (p = 0.0010) | [117] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Pirani, A.; Pettinato, G. Psychosomatic Disorders, Epigenome, and Gut Microbiota. Cells 2025, 14, 1959. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241959

Mostafavi Abdolmaleky H, Pirani A, Pettinato G. Psychosomatic Disorders, Epigenome, and Gut Microbiota. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1959. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241959

Chicago/Turabian StyleMostafavi Abdolmaleky, Hamid, Ahmad Pirani, and Giuseppe Pettinato. 2025. "Psychosomatic Disorders, Epigenome, and Gut Microbiota" Cells 14, no. 24: 1959. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241959

APA StyleMostafavi Abdolmaleky, H., Pirani, A., & Pettinato, G. (2025). Psychosomatic Disorders, Epigenome, and Gut Microbiota. Cells, 14(24), 1959. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241959