Altered Sphingolipids, Glycerophospholipids, and Lysophospholipids Reflect Disease Status in Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: A Non-Targeted Metabolomic Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

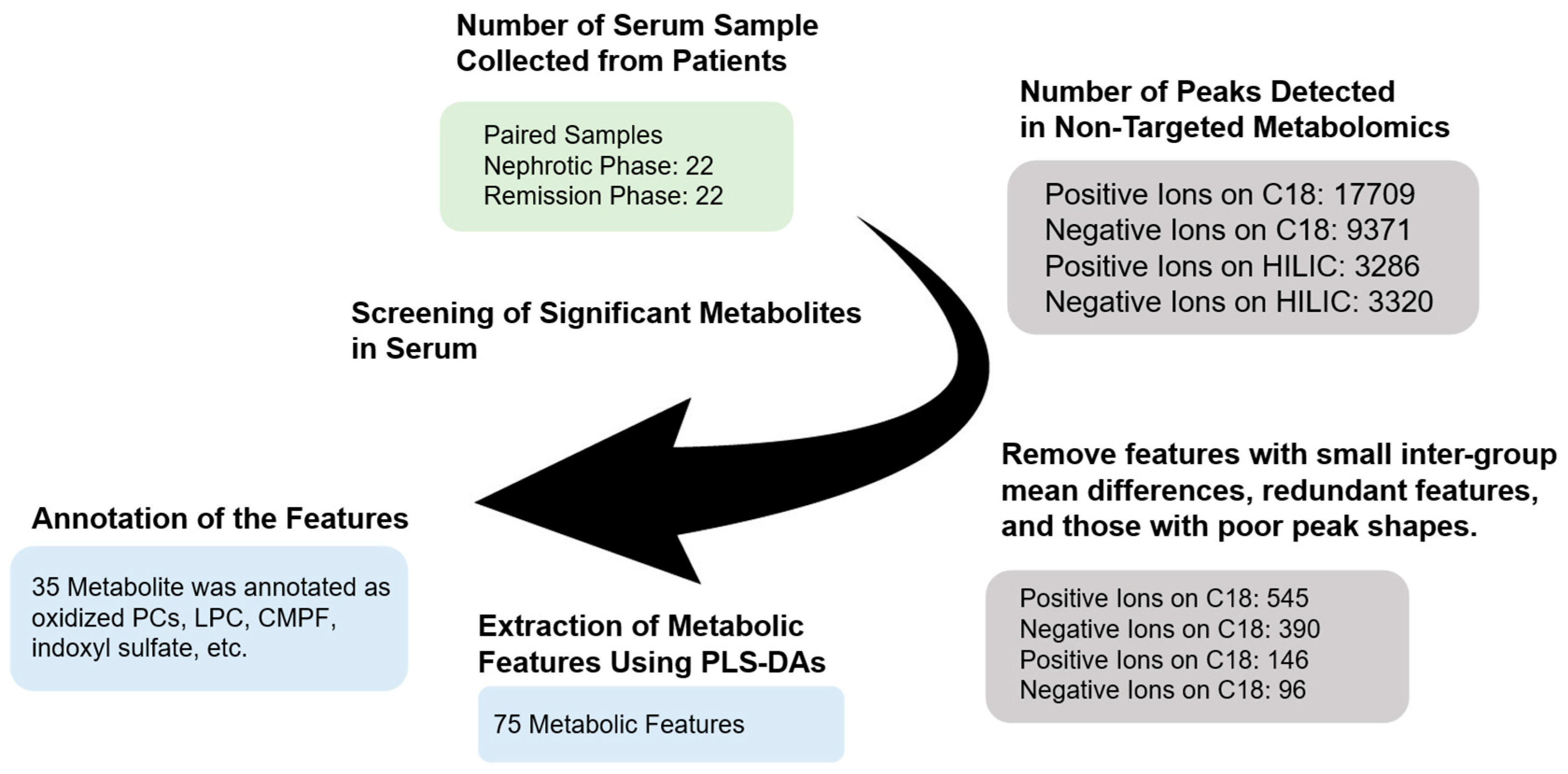

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sample Preparation for LC-MS/MS Metabolomics

2.2.2. Non-Targeted Metabolomic Analysis Using LC-QTOF-MS

2.3. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

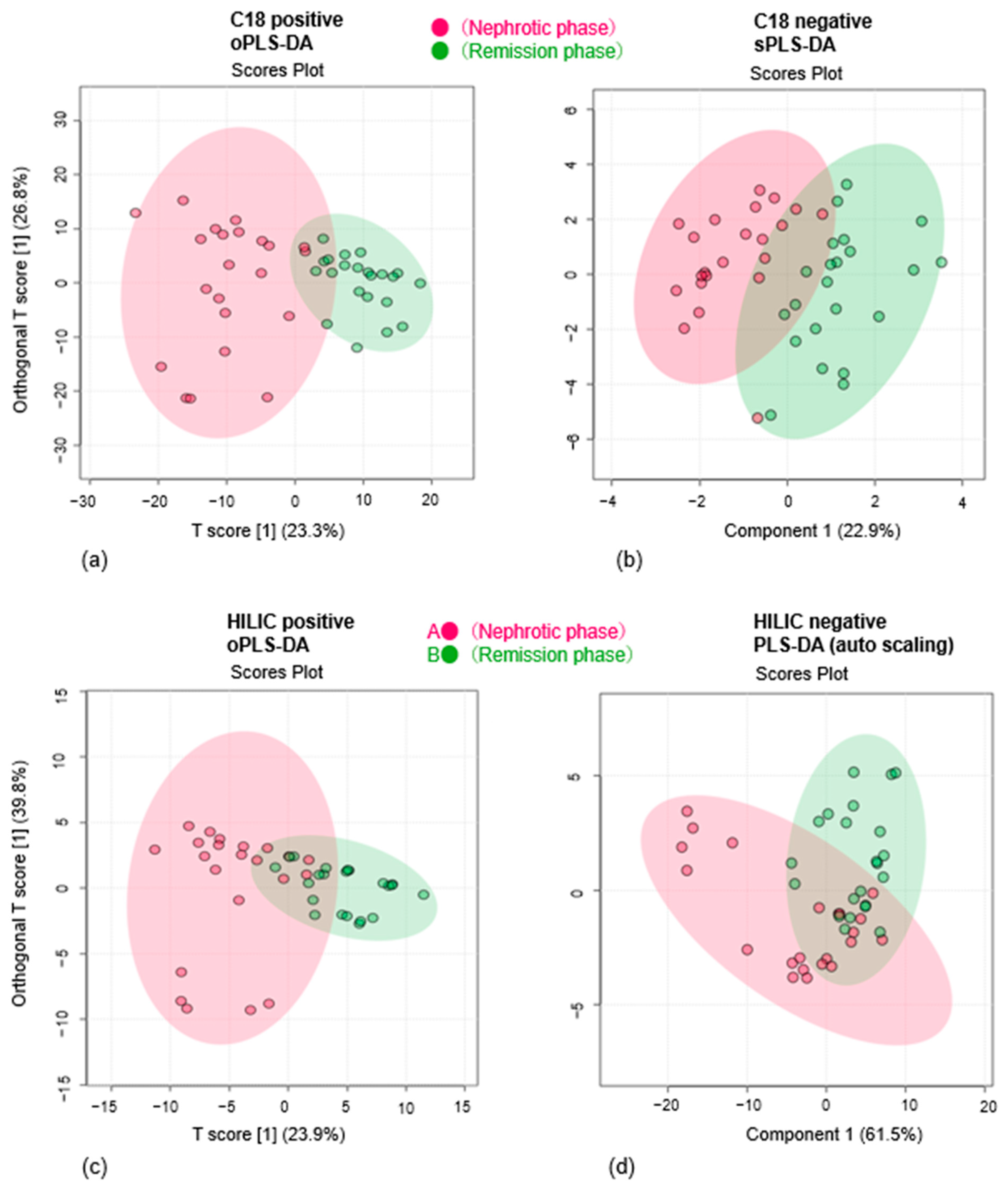

3.1. Multivariate Analysis Reveals Metabolic Differences Between Nephrotic and Remission Phases

3.2. Identification of Metabolites That Differ Between Disease Phases

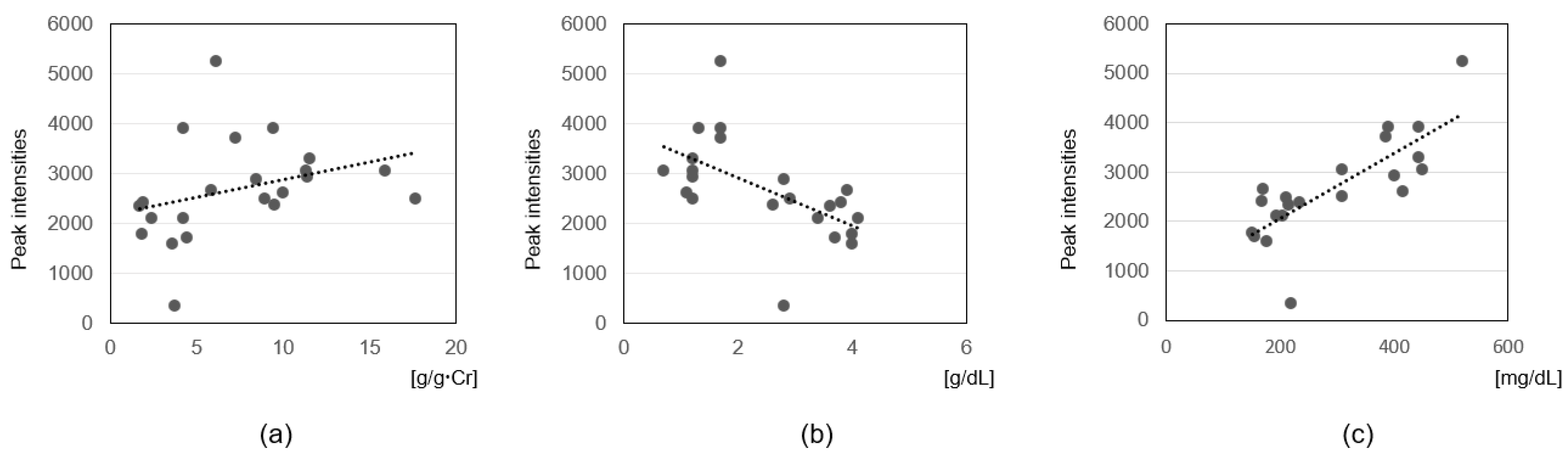

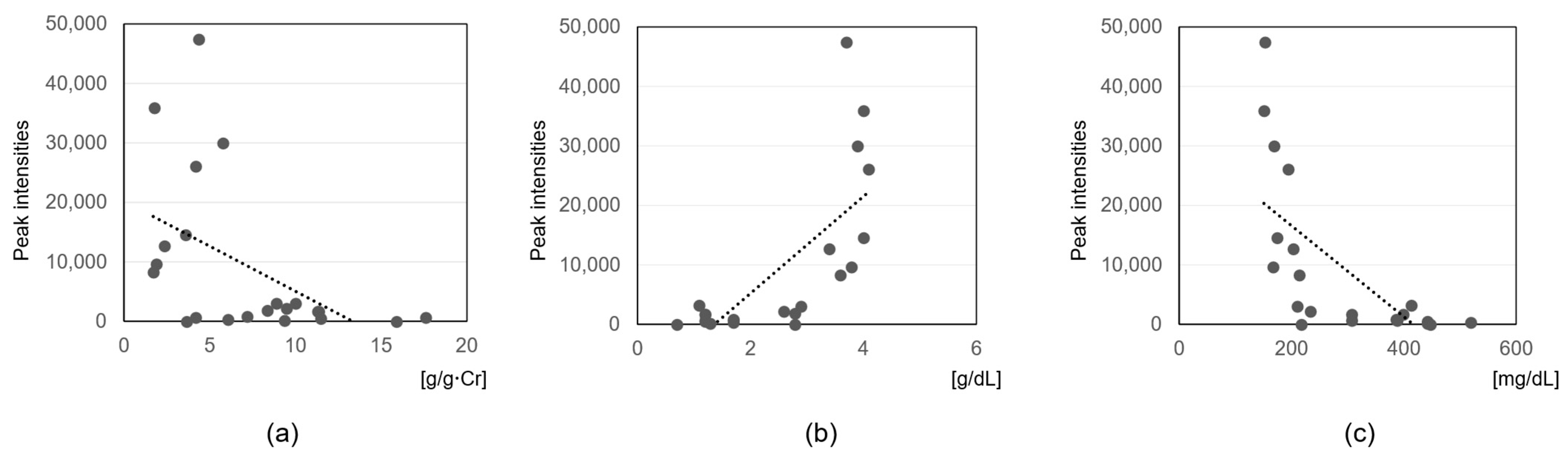

3.3. Correlation Analysis with Clinical Parameters

4. Discussion

4.1. Sphingomyelin and Proteinuria Mediated Podocyte Dysfunction

4.2. Dysregulation of Cholesterol Homeostasis Induced by Sphingomyelin, Phosphatidylcholine, and Lysophosphatidylcholine

4.3. Immunological Effects of Sphingomyelin, Phosphatidylcholine, and Lysophosphatidylcholine

4.4. Phosphatidylcholine and Mechanisms of Platelet Activation

4.5. Association of Sphingolipids and CMPF with Clinical Parameters

4.6. Oxidized Phosphatidylcholine and Pediatric ISSNS

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vivarelli, M.; Gibson, K.; Sinha, A.; Boyer, O. Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome. Lancet 2023, 402, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltkamp, F.; Rensma, L.R.; Bouts, A.H.M. Incidence and Relapse of Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome: Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020029249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: Prediction of Histopathology from Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics at Time of Diagnosis. A Report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. Kidney Int. 1978, 13, 159–165. [CrossRef]

- Trautmann, A.; Boyer, O.; Hodson, E.; Bagga, A.; Gipson, D.S.; Samuel, S.; Wetzels, J.; Alhasan, K.; Banerjee, S.; Bhimma, R.; et al. IPNA Clinical Practice Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Management of Children with Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2023, 38, 877–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalhoub, R.J. Pathogenesis of Lipoid Nephrosis: A Disorder of T-Cell Function. Lancet 1974, 2, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, K.; Tomizawa, S.; Shimabukuro, N.; Fukuda, T.; Johshita, T.; Kuroume, T. Effect of Supernatants Derived from T Lymphocyte Culture in Minimal Change Nephrotic Syndrome on Rat Kidney Capillaries. Nephron 1989, 51, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Ando, Y.; Umino, T.; Miyata, Y.; Muto, S.; Hironaka, M.; Asano, Y.; Kusano, E. Complete Remission of Minimal-Change Nephrotic Syndrome Induced by Apheresis Monotherapy. Clin. Nephrol. 2006, 65, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, R.; Yu, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, L. Metabolomics Analysis of Serum in Pediatric Nephrotic Syndrome Based on Targeted and Non-Targeted Platforms. Metabolomics 2021, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Lin, L.; Huang, G.; Xie, Y.; Peng, Z.; Liu, F.; Bai, G.; Li, W.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Metabolomic Profiles in Serum and Urine Uncover Novel Biomarkers in Children with Nephrotic Syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e13978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, R.J.; Portman, R.J.; Milliner, D.; Lemley, K.V.; Eddy, A.; Ingelfinger, J. Evaluation and Management of Proteinuria and Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: Recommendations from a Pediatric Nephrology Panel Established at the National Kidney Foundation Conference on Proteinuria, Albuminuria, Risk, Assessment, Detection, and Elimination (PARADE). Pediatrics 2000, 105, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadow, S.R.; Sarsfield, J.K. Steroid-Responsive and Nephrotic Syndrome and Allergy: Clinical Studies. Arch. Dis. Child. 1981, 56, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiso, H.; Miura, K.; Nagai, R.; Osaka, H.; Aizawa, K. Non-Targeted Metabolomics Reveal Apomorphine’s Therapeutic Effects and Lysophospholipid Alterations in Steatohepatitis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-Independent Ms/Ms Deconvolution for Comprehensive Metabolome Analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Kind, T.; Nakabayashi, R.; Yukihira, D.; Tanaka, W.; Cajka, T.; Saito, K.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. Hydrogen Rearrangement Rules: Computational Ms/Ms Fragmentation and Structure Elucidation Using MS-FINDER Software. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 7946–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramabulana, A.T.; Petras, D.; Madala, N.E.; Tugizimana, F. Metabolomics and Molecular Networking to Characterize the Chemical Space of Four Momordica Plant Species. Metabolites 2021, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigusa, D.; Okamura, Y.; Motoike, I.N.; Katoh, Y.; Kurosawa, Y.; Saijyo, R.; Koshiba, S.; Yasuda, J.; Motohashi, H.; Sugawara, J.; et al. Establishment of Protocols for Global Metabolomics by LC-MS for Biomarker Discovery. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, M.; Nimer, R.M.; Alabdaljabar, M.S.; Sabi, E.M.; Al-Ansari, M.M.; Housien, M.; Sumaily, K.M.; Dahabiyeh, L.A.; Abdel Rahman, A.M. Metabolomics Profiling of Nephrotic Syndrome Towards Biomarker Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuthier, R.E. Lipid Composition of Isolated Epiphyseal Cartilage Cells, Membranes and Matrix Vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1975, 409, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendrasiak, G.L.; Smith, R.L. The Effect of the Choline Head Group on Phospholipid Hydration. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2001, 113, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsecchi, M.; Cazzetta, V.; Oriolo, F.; Lan, X.; Piazza, R.; Saleem, M.A.; Singhal, P.C.; Mavilio, D.; Mikulak, J.; Aureli, M. APOL1 Polymorphism Modulates Sphingolipid Profile of Human Podocytes. Glycoconj. J. 2020, 37, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafft, C.A.; Fervenza, F.C.; Semret, M.H.; Orloff, S.; Sethi, S. Renal Involvement in Neimann-Pick Disease. NDT Plus 2009, 2, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintavorn, P.; Munie, S.; Munagapati, S. Lamellar Bodies in Podocytes Associated With Compound Heterozygous Mutations for Niemann Pick Type C1 Mimicking Fabry Disease, a Case Report. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2022, 9, 20543581221124635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Hirono, K.; Aizawa, T.; Tsugawa, K.; Joh, K.; Imaizumi, T.; Tanaka, H. Podocyte Sphingomyelin Phosphodiesterase Acid-Like 3b Decreases among Children with Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2021, 25, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merscher, S.; Fornoni, A. Podocyte Pathology and Nephropathy—Sphingolipids in Glomerular Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, M.; Shimizu, A.; Hanekamp, I.; Torabi, R.; Villani, V.; Yamada, K. Rituximab Treatment Prevents the Early Development of Proteinuria Following Pig-to-Baboon Xeno-Kidney Transplantation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaiah, P.V.; Liu, M. Role of Sphingomyelin in the Regulation of Cholesterol Esterification in the Plasma Lipoproteins. Inhibition of Lecithin-Cholesterol Acyltransferase Reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 20156–20163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hevonoja, T.; Pentikäinen, M.O.; Hyvönen, M.T.; Kovanen, P.T.; Ala-Korpela, M. Structure of Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL) Particles: Basis for Understanding Molecular Changes in Modified Ldl. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1488, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Silva, R.A.; Jerome, W.G.; Kontush, A.; Chapman, M.J.; Curtiss, L.K.; Hodges, T.J.; Davidson, W.S. Apolipoprotein a-I Structural Organization in High-Density Lipoproteins Isolated from Human Plasma. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowerah, P.; Gogoi, A.; Shira, C.D.; Sarkar, B.; Mazumdar, S. A Study of Dyslipidemia and Its Clinical Implications in Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome. Cureus 2023, 15, e47434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, T.; Yamagata, T.; Ito, T.; Odaka, J.; Saito, T.; Aoyagi, J.; Momoi, M.Y. Apolipoprotein Aii Levels Are Associated with the up/Ucr Levels in Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2015, 19, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sain-van der Velden, M.G.; Kaysen, G.A.; Barrett, H.A.; Stellaard, F.; Gadellaa, M.M.; Voorbij, H.A.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Rabelink, T.J. Increased Vldl in Nephrotic Patients Results from a Decreased Catabolism While Increased Ldl Results from Increased Synthesis. Kidney Int. 1998, 53, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joven, J.; Villabona, C.; Vilella, E.; Masana, L.; Albertí, R.; Vallés, M. Abnormalities of Lipoprotein Metabolism in Patients with the Nephrotic Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, T.; Shiraishi, H.; Yamagata, T.; Ito, T.; Odaka, J.; Saito, T.; Aoyagi, J.; Momoi, M.Y. Th2 Cells Predominate in Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2010, 14, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, T.; Yamagata, T.; Momoi, M.Y. Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1beta and Interleukin-8 Associated with Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome. Pediatr. Int. 2009, 51, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, M.J.; Meyer-Jark, T.; Lilova, M.; Müller-Wiefel, D.E. Combined T- and B-Cell Activation in Childhood Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome. Clin. Nephrol. 2003, 60, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinque, B.; Di Marzio, L.; Centi, C.; Di Rocco, C.; Riccardi, C.; Grazia Cifone, M. Sphingolipids and the Immune System. Pharmacol. Res. 2003, 47, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyersdorf, N.; Müller, N. Sphingomyelin Breakdown in T Cells: Role in Activation, Effector Functions and Immunoregulation. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, E.A.; Oszvald, Á.; Péter, M.; Balogh, G.; Osteikoetxea-Molnár, A.; Bozó, T.; Szabó-Meleg, E.; Nyitrai, M.; Derényi, I.; Kellermayer, M.; et al. Nanotubes Connecting B Lymphocytes: High Impact of Differentiation-Dependent Lipid Composition on Their Growth and Mechanics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, K.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Diao, H. Phospholipid Metabolites of the Gut Microbiota Promote Hypoxia-Induced Intestinal Injury Via Cd1d-Dependent γδ T Cells. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2096994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusnak, T.; Azarcoya-Barrera, J.; Makarowski, A.; Jacobs, R.L.; Richard, C. Plant- and Animal-Derived Dietary Sources of Phosphatidylcholine Have Differential Effects on Immune Function in the Context of a High-Fat Diet in Male Wistar Rats. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 1936–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauvi, D.M.; Hawisher, D.; Derunes, J.; Rodriguez, E.; De Maio, A. Membrane Phospholipids Activate the Inflammatory Response in Macrophages by Various Mechanisms. Faseb J. 2024, 38, e23619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.C.; Clardy, J. Spontaneous Generation of an Endogenous RORγt Agonist. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 11688–11692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.M.; You, J.K.; Li, G.; Kim, J.; Singh, A.; Morstein, J.; Trauner, D.; Pereira de Sá, N.; Normile, T.G.; Farnoud, A.M.; et al. Cholesterol and Sphingomyelin Are Critical for Fcγ Receptor-Mediated Phagocytosis of Cryptococcus Neoformans by Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, Y.; Oka, M.; Yoshida, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Nishizuka, Y. Role of Lysophosphatidylcholine in T-Lymphocyte Activation: Involvement of Phospholipase A2 in Signal Transduction through Protein Kinase C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 6447–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimoyama, H.; Nakajima, M.; Naka, H.; Maruhashi, Y.; Akazawa, H.; Ueda, T.; Nishiguchi, M.; Yamoto, Y.; Kamitsuji, H.; Yoshioka, A. Up-Regulation of Interleukin-2 mRNA in Children with Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2004, 19, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwenya, B.Z.; Foster, D.M. Enhancement of Antibody Production by Lysophosphatidylcholine and Alkylglycerol. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1991, 196, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, F. Cdp-Choline:Alkylacetylglycerol Cholinephosphotransferase Catalyzes the Final Step in the de Novo Synthesis of Platelet-Activating Factor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1348, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneman, B.; Levtchenko, E.; van den Heuvel, B.; Van Geet, C.; Freson, K. Platelet Abnormalities in Nephrotic Syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2016, 31, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.V.; Schumacher, W.A.; Kunkel, S.L.; Driscoll, E.M.; Lucchesi, B.R. Platelet-Activating Factor and the Release of a Platelet-Derived Coronary Artery Vasodilator Substance in the Canine. Circ. Res. 1986, 58, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garin, E.H. Circulating Mediators of Proteinuria in Idiopathic Minimal Lesion Nephrotic Syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2000, 14, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüseyinov, A.; Kantar, M.; Mir, S.; Coker, I.; Kabasakal, C.; Cura, A. Plasma and Urinary Platelet Activating Factor Concentrations and Leukotriene Releasing Activity of Leukocytes in Steroid Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome of Childhood. Acta Paediatr. Jpn. 1998, 40, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsuya, K.; Kaneko, K.; Kasahara, K. Function of Platelet Glycosphingolipid Microdomains/Lipid Rafts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, P.; Nienaber, F.; Zaldivia, M.T.K.; Stamm, J.; Siegel, P.M.; Mellett, N.A.; Wessinger, M.; Wang, X.; McFadyen, J.D.; Bassler, N.; et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine Is a Major Component of Platelet Microvesicles Promoting Platelet Activation and Reporting Atherosclerotic Plaque Instability. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 119, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kidd, J.; Gehr, T.W.B.; Li, P.L. Podocyte Sphingolipid Signaling in Nephrotic Syndrome. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 55, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, B.K.; Bammens, B.; Verbeke, K.; Evenepoel, P. A Review of Albumin Binding in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008, 51, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Tian, H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Ding, F. Improved Dialysis Removal of Protein-Bound Uraemic Toxins with a Combined Displacement and Adsorption Technique. Blood Purif. 2022, 51, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikitake, Y.; Hirata, K.; Kawashima, S.; Inoue, N.; Akita, H.; Kawai, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Yokoyama, M. Inhibition of Endothelium-Dependent Arterial Relaxation by Oxidized Phosphatidylcholine. Atherosclerosis 2000, 152, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwołińska, D.; Grzeszczak, W.; Szczepańska, M.; Kiliś-Pstrusińska, K.; Szprynger, K. Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Enzymes in Children on Maintenance Dialysis. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2006, 21, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Maurício, T.; Domingues, R.; Domingues, P. Impact of Oxidized Phosphatidylcholine Supplementation on the Lipidome of Raw264.7 Macrophages. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 768, 110384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelatha, S.; D’souza, B.; D’souza, V.; Rajendiran, K. Role of Oxidant-Antioxidant Enzymes in Managing the Cardiovascular Risks in Nephrotic Syndrome Patients. J. Nephropathol. 2022, 11, e17276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbkowski, K.; Kreft, E.; Sałaga-Zaleska, K.; Chyła-Danił, G.; Mickiewicz, A.; Gruchała, M.; Kuchta, A.; Jankowski, M. Human In Vitro Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (Oxldl) Increases Urinary Albumin Excretion in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkan, E.; Zhao, X.; Setchell, K.; Devarajan, P. Distinct Urinary Lipid Profile in Children with Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2016, 31, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Annotated Compounds | FC | p Values | q Values | Adduct Type | m/z | LC Mode | RT (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC(16:0/18:2)+O | 5.599 | 0.026802 | 0.044286 | [M+HCOO]− | 818.563 | C18 | 11.281 |

| PC(16:0/22:6)+2O | 5.049 | 0.025874 | 0.041429 | [M+HCOO]− | 882.557 | C18 | 11.096 |

| PC(18:0/18:2)+O | 4.207 | 0.017478 | 0.04 | [M+HCOO]− | 846.593 | C18 | 12.076 |

| LPC(17:0) | 3.038 | 0.003903 | 0.028571 | [M+HCOO]− | 554.351 | C18 | 9.3 |

| LPC(18:0) | 2.329 | 0.002104 | 0.024286 | [M+HCOO]− | 568.367 | C18 | 9.479 |

| PC(16:0/20:3) | 2.319 | 0.007069 | 0.034286 | [M+HCOO]− | 828.583 | C18 | 13.633 |

| LPE(18:0) | 1.848 | 0.002407 | 0.027143 | [M−H]− | 480.313 | C18 | 9.679 |

| PC(16:0/22:4) | 1.685 | 0.010441 | 0.037143 | [M+HCOO]− | 854.597 | C18 | 13.608 |

| LPC(20:2) | 1.661 | 0.000149 | 0.011429 | [M+HCOO]− | 592.367 | C18 | 9.22 |

| LPC(16:0) | 1.639 | 0.000252 | 0.014286 | [M+HCOO]− | 540.335 | C18 | 8.819 |

| SM(d34:2) | 1.608 | 0.000136 | 0.008571 | [M+HCOO]− | 745.556 | C18 | 12.654 |

| SM(d33:1) | 1.577 | 0.000323 | 0.015714 | [M+HCOO]− | 733.556 | C18 | 12.697 |

| PC(18:0/20:2) | 1.576 | 0.000141 | 0.01 | [M+HCOO]− | 858.631 | C18 | 15.066 |

| PC(35:1) | 1.54 | 0.000085 | 0.007143 | [M+HCOO]− | 818.599 | C18 | 14.435 |

| SM(d34:1) | 1.534 | 0.000483 | 0.018571 | [M+HCOO−C2H4O2]− | 687.55 | C18 | 12.976 |

| PC(18:1/20:3) | 1.522 | 0.006156 | 0.031429 | [M+HCOO]− | 854.598 | C18 | 13.454 |

| SM(d32:1) | 1.519 | 0.001116 | 0.022857 | [M+HCOO]− | 719.541 | C18 | 12.257 |

| PC(38:3) | 1.5 | 0.006332 | 0.032857 | [M+HCOO]− | 856.605 | C18 | 13.455 |

| ΔFA(18:1)+3O | 7.738 | 0.046204 | 0.05 | [M−H]− | 329.236 | C18 | 7.358 |

| ΔcPA(16:0) | 5.693 | 0.005325 | 0.03 | [M−H]− | 391.228 | C18 | 8.987 |

| ΔPyroglutamylglycine | 3.304 | 0.012598 | 0.038571 | [M+H]+ | 187.073 | HILIC | 2.902 |

| ΔGlutamylglutamate | 2.405 | 0.000032 | 0.002857 | [M+H]+ | 277.109 | HILIC | 0.961 |

| ΔPyroglutaminylglutamine or Methylcytidine | 2.24 | 0.035083 | 0.048571 | [M+H]+ | 258.111 | HILIC | 3.043 |

| ΔPyroglutamylglycine | 2.204 | 0.028601 | 0.047143 | [M+H]+ | 187.073 | HILIC | 2.766 |

| Δc-Glutamylglutamic acid | 1.858 | 0.008448 | 0.035714 | [M+H]+ | 277.104 | HILIC | 6.346 |

| ΔAsparaginylvaline | 1.751 | 0.02629 | 0.042857 | [M+H]+ | 232.131 | HILIC | 3.044 |

| ΔPC(34:2) | 1.693 | 0.028382 | 0.045714 | [M+H]+ | 758.616 | C18 | 13.249 |

| ΔSM(d18:1/16:0)+O | 1.636 | 0.000041 | 0.004286 | [M+HCOO]− | 763.568 | C18 | 11.783 |

| ΔPC(36:2) | 1.545 | 0.002177 | 0.025714 | [M+H]+ | 786.607 | C18 | 13.409 |

| Annotated Compounds | FC | p Values | q Values | Adduct Type | m/z | LC Mode | RT (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMPeF | 0.249 | 0.00001 | 0.0014286 | [M−H]− | 267.1245 | C18 | 7.879 |

| CMPF | 0.264 | 0.000066 | 0.0057143 | [M−H]− | 239.094 | C18 | 7.376 |

| DPMPS | 0.267 | 0.000549 | 0.02 | [M−H]− | 453.088 | HILIC | 2.581 |

| HOCPS | 0.34 | 0.000557 | 0.0214286 | [M−H]− | 439.072 | HILIC | 2.822 |

| Indoxyl sulfate | 0.492 | 0.000337 | 0.0171429 | [M−H]− | 212.004 | C18 | 5.606 |

| ΔPDMS | 0.461 | 0.000151 | 0.0128571 | [M+H]+ | 536.17 | C18 | 12.809 |

| Classification | Full Names | Abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid classes | Sphingolipids | Sphingomyelin | SM |

| Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylcholine | PC | |

| Lysophospholipids | Lysophosphatidylcholine | LPC | |

| Lysophosphatidylethanoamine | LPE | ||

| Uremic toxins | 3-carboxy-4-methyl-5-propyl-2-furanpropionic acid | CPMF | |

| Indoxyl sulfate |

| Annotated Compounds | FC | Correlation Efficient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UP/UCr | Serum Alb | Serum T.chol | ||

| SM(d34:2) | 1.608 | 0.611 | −0.648 | 0.676 |

| LPE(18:0) | 1.848 | 0.606 | ||

| SM(d33:1) | 1.577 | 0.684 | ||

| SM(d34:1) | 1.534 | 0.632 | ||

| SM(d32:1) | 1.519 | −0.634 | 0.698 | |

| CMPeF | 0.249 | −0.725 | 0.831 | −0.752 |

| CMPF | 0.264 | −0.606 | 0.747 | −0.836 |

| DPMPS | 0.267 | 0.768 | −0.725 | |

| HOCPS | 0.340 | 0.679 | −0.657 | |

| Indoxyl sulfate | 0.492 | 0.719 | ||

| ΔSM(d18:1/16:0)+O | 1.636 | 0.646 | −0.624 | 0.699 |

| ΔGlutamylglutamate | 2.405 | −0.606 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanai, T.; Ogiso, H.; Aoyagi, J.; Kurosaki, M.; Maru, T.; Ishii, M.; Tanimoto, K.; Yoshino, M.; Yamashita, Y.; Tajima, T.; et al. Altered Sphingolipids, Glycerophospholipids, and Lysophospholipids Reflect Disease Status in Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: A Non-Targeted Metabolomic Study. Cells 2025, 14, 1950. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241950

Kanai T, Ogiso H, Aoyagi J, Kurosaki M, Maru T, Ishii M, Tanimoto K, Yoshino M, Yamashita Y, Tajima T, et al. Altered Sphingolipids, Glycerophospholipids, and Lysophospholipids Reflect Disease Status in Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: A Non-Targeted Metabolomic Study. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1950. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241950

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanai, Takahiro, Hideo Ogiso, Jun Aoyagi, Masanori Kurosaki, Tomomi Maru, Marika Ishii, Kazuya Tanimoto, Mitsuaki Yoshino, Yuri Yamashita, Toshihiro Tajima, and et al. 2025. "Altered Sphingolipids, Glycerophospholipids, and Lysophospholipids Reflect Disease Status in Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: A Non-Targeted Metabolomic Study" Cells 14, no. 24: 1950. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241950

APA StyleKanai, T., Ogiso, H., Aoyagi, J., Kurosaki, M., Maru, T., Ishii, M., Tanimoto, K., Yoshino, M., Yamashita, Y., Tajima, T., Nagai, R., & Aizawa, K. (2025). Altered Sphingolipids, Glycerophospholipids, and Lysophospholipids Reflect Disease Status in Idiopathic Steroid-Sensitive Nephrotic Syndrome in Children: A Non-Targeted Metabolomic Study. Cells, 14(24), 1950. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241950