Durable Global Correction of CNS and PNS and Lifespan Rescue in Murine Globoid Cell Leukodystrophy via AAV9-Mediated Monotherapy

Highlights

- A single, region-specific intracranial dose of AAV9-GALC achieves widespread CNS-PNS biodistribution, sustained supraphysiological GALC activity, and complete lifelong psychosine normalization in Twitcher mice.

- This streamlined monotherapy preserves myelin integrity, proteostasis, and motor function, leading to near–wild-type lifespan without the need for HSCT, repeated dosing, multi-route administration, or high systemic AAV exposure.

- Demonstrating durable metabolic and structural correction after a single intracranial dose provides strong rationale for translational intracerebral AAV9 strategies that minimize procedural burden and systemic risks.

- These results establish a practical therapeutic framework for GLD, highlighting the feasibility of achieving long-term CNS-PNS wide correction through targeted, low-exposure gene delivery.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Therapy

2.2. Vector Production

2.3. GALC Activity

2.4. Psychosine Concentration

2.5. Immunofluorescences

2.6. X-Gal Histochemistry

2.7. In Situ Hybridization

2.8. Quantification of Viral Genomes by ddPCR

2.9. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.10. Survival and Phenotype

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survival and Weight and Behavioral Assessment

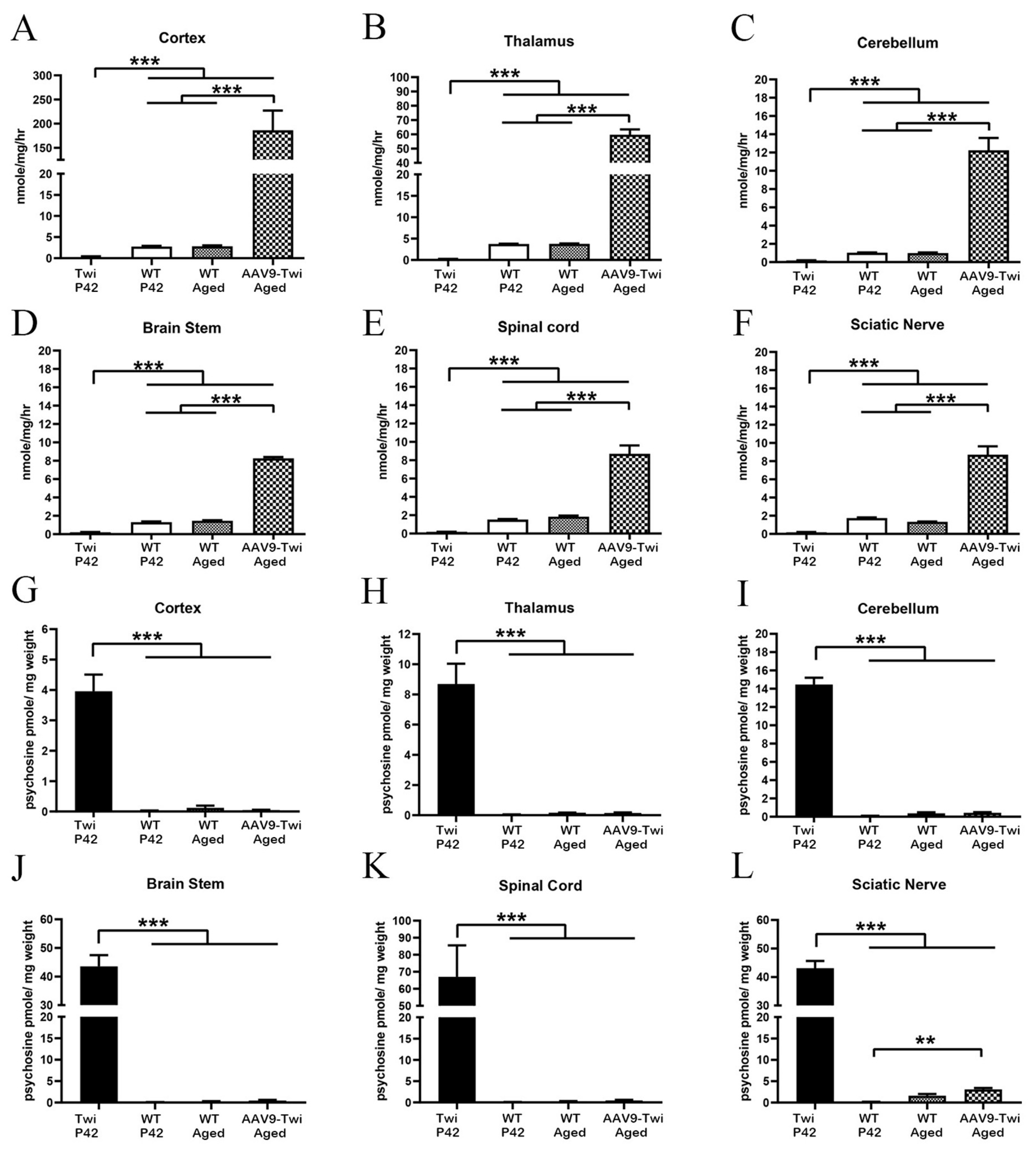

3.2. Supraphysiological Levels of GALC Activity

3.3. Normalization of Psychosine Concentration

3.4. Intense and Broad GALC Expression

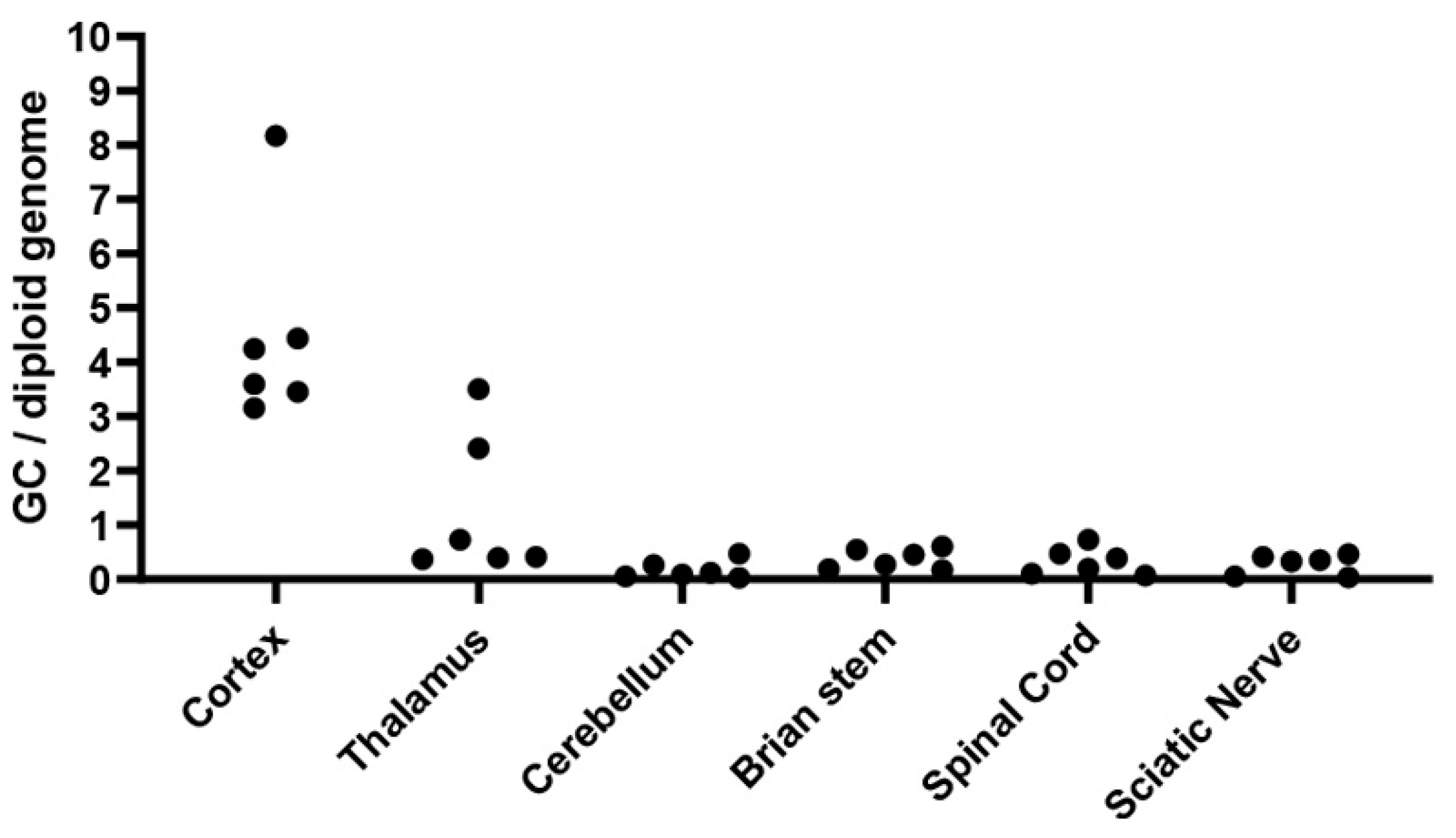

3.5. Sustained and Widespread Biodistribution

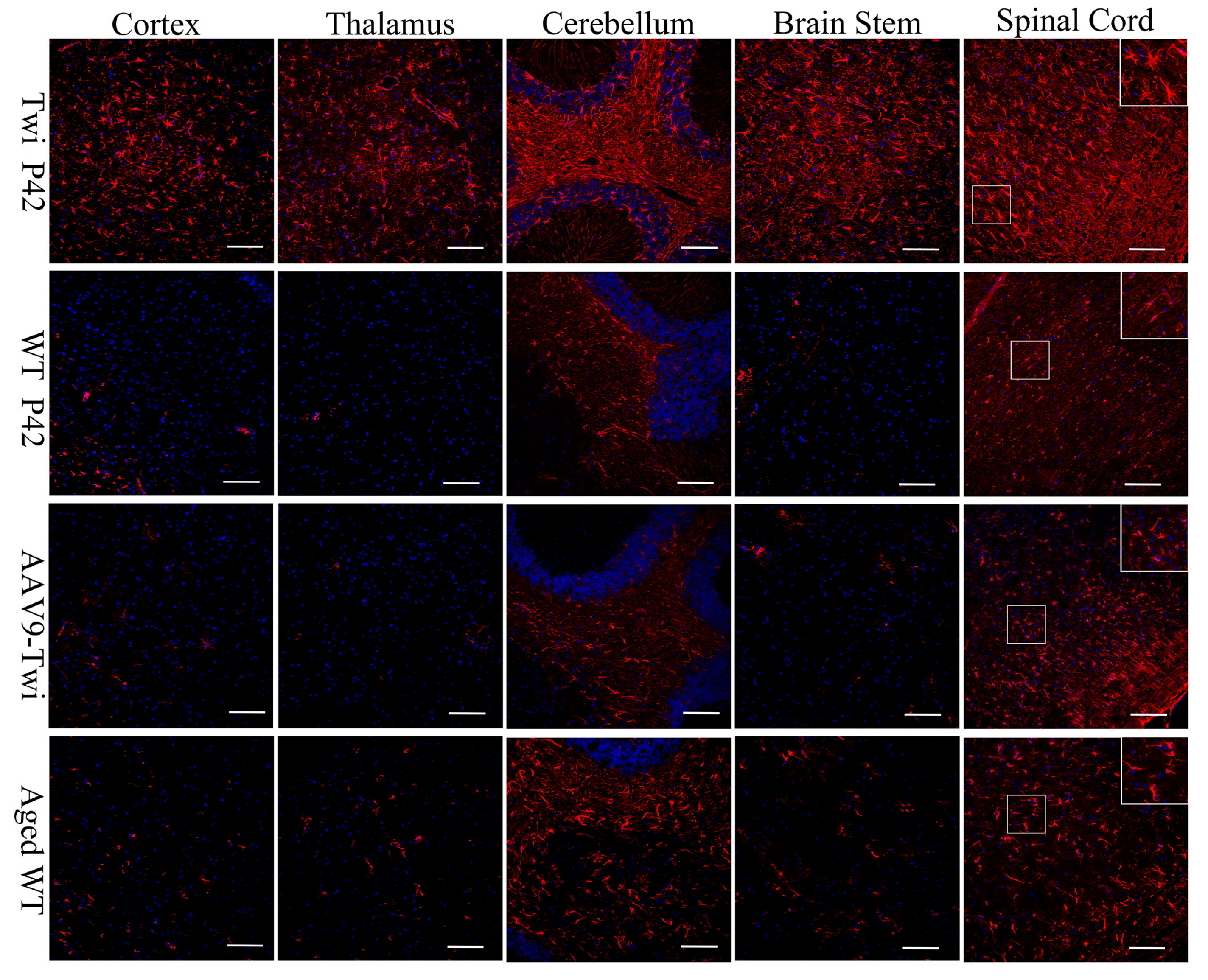

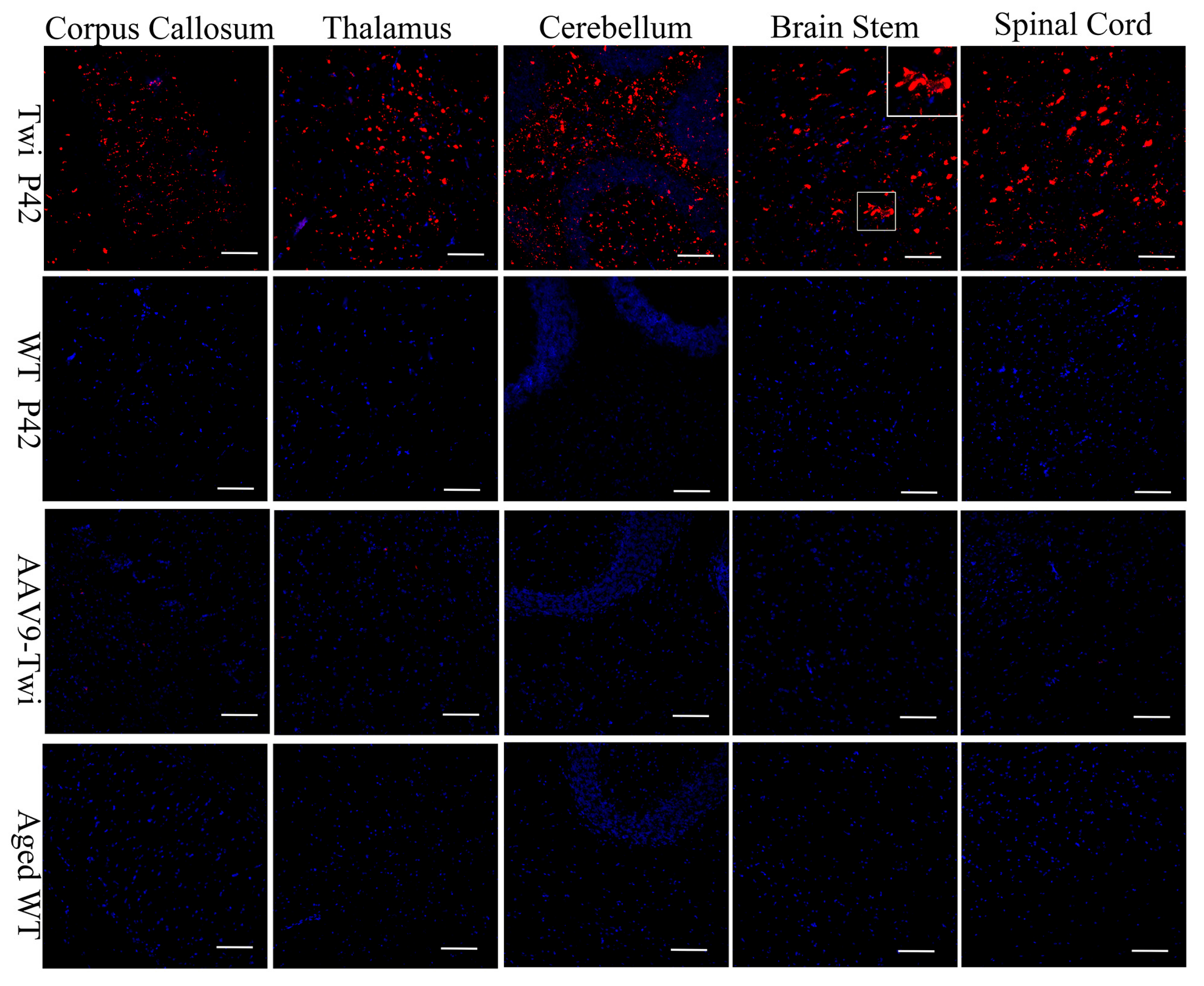

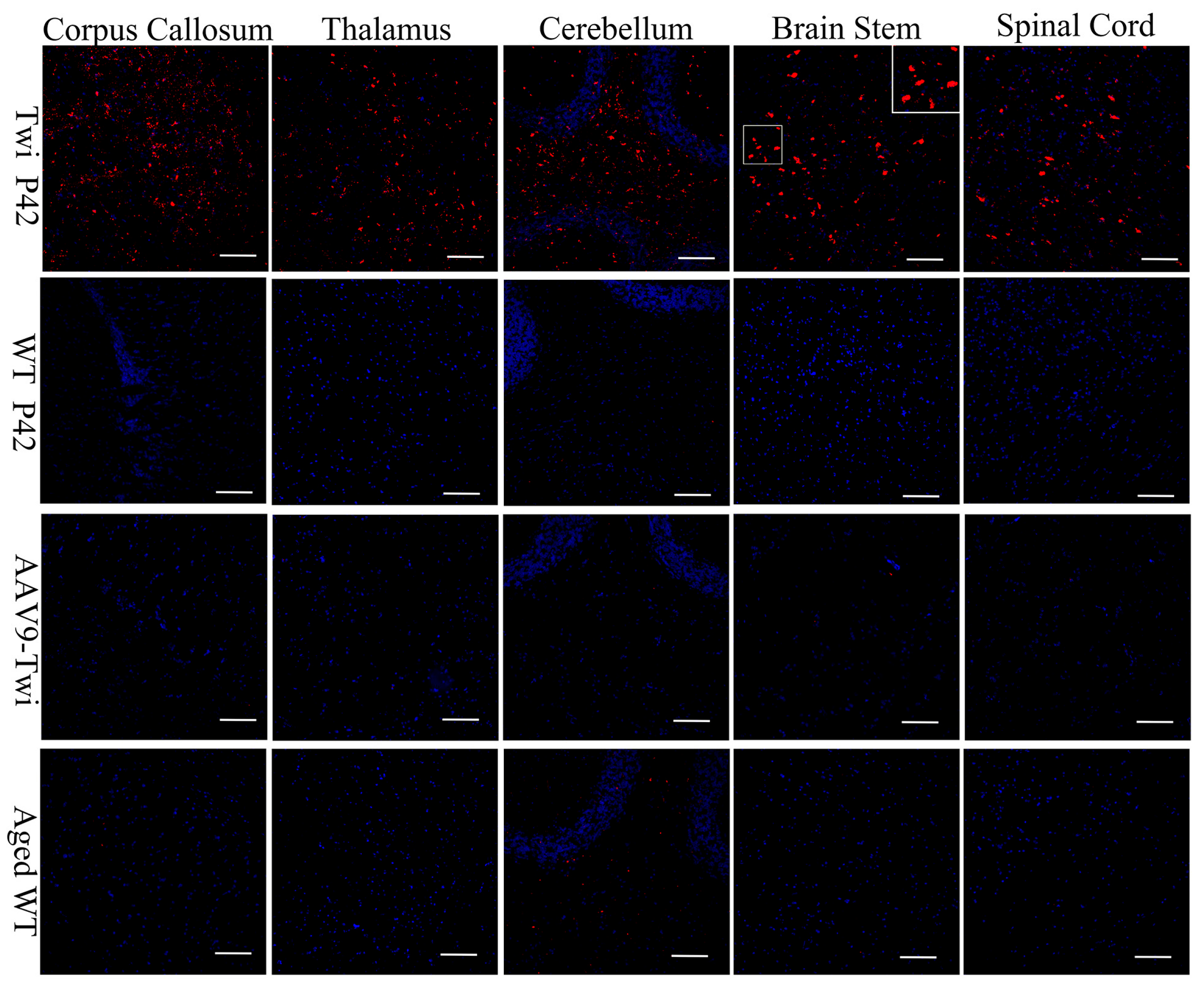

3.6. Reduction of Neuroinflammation

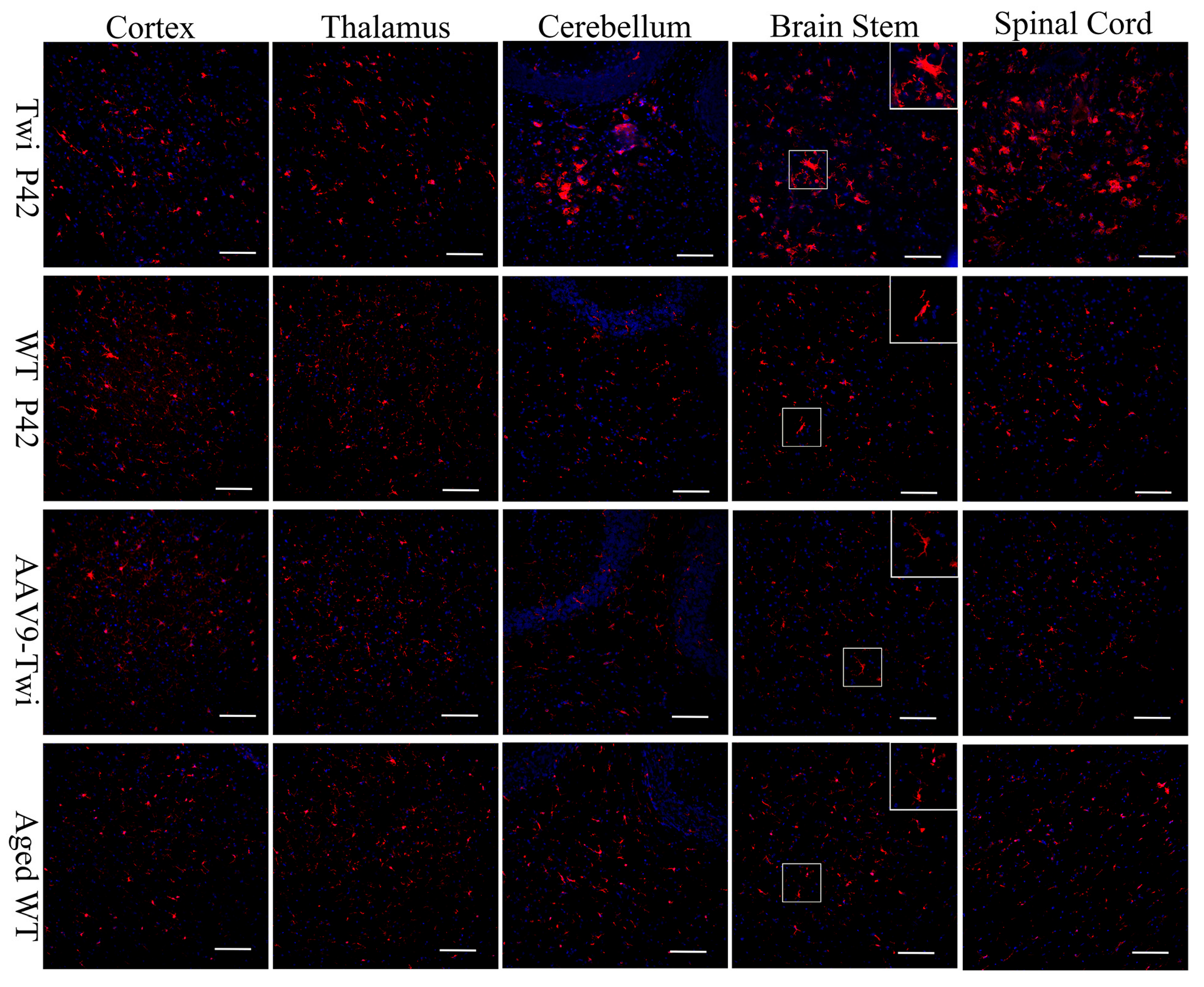

3.7. Preservation of Proteostasis

3.8. Preservation of Myelination and Axon Integerity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suzuki, K. Globoid cell leukodystrophy (Krabbe’s disease): Update. J. Child Neurol. 2003, 18, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.R.; Lopez, M.A.; Beltran-Quintero, M.L.; Tuc Bengur, E.; Poe, M.D.; Escolar, M.L. Infantile Krabbe disease (0–12 months), progression, and recommended endpoints for clinical trials. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2024, 11, 3064–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.B.; Givogri, M.I.; Lopez-Rosas, A.; Cao, H.; van Breemen, R.; Thinakaran, G.; Bongarzone, E.R. Psychosine accumulates in membrane microdomains in the brain of krabbe patients, disrupting the raft architecture. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 6068–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.S.; Ho, C.S.; Huang, Y.W.; Wu, T.Y.; Lee, T.H.; Huang, Z.D.; Wang, T.J.; Yang, S.J.; Chiang, M.F. Impairment of Proteasome and Autophagy Underlying the Pathogenesis of Leukodystrophy. Cells 2020, 9, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Grosso, A.; Angella, L.; Tonazzini, I.; Moscardini, A.; Giordano, N.; Caleo, M.; Rocchiccioli, S.; Cecchini, M. Dysregulated autophagy as a new aspect of the molecular pathogenesis of Krabbe disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 129, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Taniike, M. Murine model of genetic demyelinating disease: The twitcher mouse. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1995, 32, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, A.; Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; Suzuki, K.; Poorthuis, B.J.; Van Bekkum, D.W.; Suzuki, K. Pathology of the peripheral nerve in the twitcher mouse following bone marrow transplantation. Brain Res. 1988, 460, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Courtenay, A.; Troendle, F.J.; Stallings-Mann, M.L.; Dickey, C.A.; DeLucia, M.W.; Dickson, D.W.; Eckman, C.B. Enzyme replacement therapy results in substantial improvements in early clinical phenotype in a mouse model of globoid cell leukodystrophy. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1549–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Le Vine, S.M. Substrate-reduction therapy enhances the benefits of bone marrow transplantation in young mice with globoid cell leukodystrophy. Pediatr. Res. 2002, 51, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, G.; Bradbury, A.M.; Sands, M.S.; Bongarzone, E.R. Preclinical studies in Krabbe disease: A model for the investigation of novel combination therapies for lysosomal storage diseases. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, N.; Inui, K.; Tatsumi, N.; Fukushima, H.; Nishigaki, T.; Taniike, M.; Nishimoto, J.; Tsukamoto, H.; Yanagihara, I.; Ozono, K.; et al. Molecular cloning and expression of cDNA for murine galactocerebrosidase and mutation analysis of the twitcher mouse, a model of Krabbe’s disease. J. Neurochem. 1996, 66, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, S.; Tiribuzi, R.; Tortori, A.; Conti, D.; Visigalli, I.; Lattanzi, A.; Biffi, A.; Gritti, A.; Orlacchio, A. Specific determination of beta-galactocerebrosidase activity via competitive inhibition of beta-galactosidase. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S.I.; Sato, S.; Otake, K.; Kosugi, Y. Highly-sensitive simultaneous quantitation of glucosylsphingosine and galactosylsphingosine in human cerebrospinal fluid by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 217, 114852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbens, J.J.; Moser, A.B.; Hubbard, W.C.; Bongarzone, E.R.; Maegawa, G.H. Characterization and application of a disease-cell model for a neurodegenerative lysosomal disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014, 111, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcetta, D.; Perani, L.; Givogri, M.I.; Galbiati, F.; Orlacchio, A.; Martino, S.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Bongarzone, E. Analysis of galactocerebrosidase activity in the mouse brain by a new histological staining method. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 77, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Donsante, A.; Macauley, S.; Levy, B.; Vogler, C.; Sands, M.S. Central nervous system-directed AAV2/5-mediated gene therapy synergizes with bone marrow transplantation in the murine model of globoid-cell leukodystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Fantz, C.R.; Levy, B.; Rafi, M.A.; Vogler, C.; Wenger, D.A.; Sands, M.S. AAV2/5 vector expressing galactocerebrosidase ameliorates CNS disease in the murine model of globoid-cell leukodystrophy more efficiently than AAV2. Mol. Ther. 2005, 12, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, D.C.; Fisher, E.M.; Brown, S.D.; Peters, J.; Hunter, A.J.; Martin, J.E. Behavioral and functional analysis of mouse phenotype: SHIRPA, a proposed protocol for comprehensive phenotype assessment. Mamm. Genome 1997, 8, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, K.; Kabuto, H.; Makino, H.; Ogawa, N. Pole test is a useful method for evaluating the mouse movement disorder caused by striatal dopamine depletion. J. Neurosci. Methods 1997, 73, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniike, M.; Suzuki, K. Spacio-temporal progression of demyelination in twitcher mouse: With clinico-pathological correlation. Acta Neuropathol. 1994, 88, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, M.; Komiyama, A.; Martin, P.M.; Suzuki, K. Proliferation of microglia/macrophages in the demyelinating CNS and PNS of twitcher mouse. Brain Res. 1993, 602, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, G.B.; Petryniak, M.A. Neuroimmune mechanisms in Krabbe’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 94, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicaise, A.M.; Bongarzone, E.R.; Crocker, S.J. A microglial hypothesis of globoid cell leukodystrophy pathology. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 94, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon-Gonzalez, M.B.; Wang, S.; Cox, T.M. Expression of Ripk1 and DAM genes correlates with severity and progression of Krabbe disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, 2082–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.; Vitelli, C.; Yu, G.K.; Pacheco, G.; Vincelette, J.; Bunting, S.; Siso, S. Quantitative Assessment of Neuroinflammation, Myelinogenesis, Demyelination, and Nerve Fiber Regeneration in Immunostained Sciatic Nerves from Twitcher Mice with a Tissue Image Analysis Platform. Toxicol. Pathol. 2021, 49, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, H.; Suzuki, K. Demyelination in the spinal cord of murine globoid cell leukodystrophy (the twitcher mouse). Acta Neuropathol. 1984, 62, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.; Galbiati, F.; Castelvetri, L.C.; Givogri, M.I.; Lopez-Rosas, A.; Bongarzone, E.R. Peripheral neuropathy in the Twitcher mouse involves the activation of axonal caspase 3. ASN Neuro 2011, 3, AN20110019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, M.A.; Rao, H.Z.; Passini, M.A.; Curtis, M.; Vanier, M.T.; Zaka, M.; Luzi, P.; Wolfe, J.H.; Wenger, D.A. AAV-mediated expression of galactocerebrosidase in brain results in attenuated symptoms and extended life span in murine models of globoid cell leukodystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2005, 11, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.S.; Hsiao, C.D.; Liau, I.; Lin, S.P.; Chiang, M.F.; Chuang, C.K.; Wang, T.J.; Wu, T.Y.; Jian, Y.R.; Huang, S.F.; et al. CNS-targeted AAV5 gene transfer results in global dispersal of vector and prevention of morphological and function deterioration in CNS of globoid cell leukodystrophy mouse model. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2011, 103, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.-S.; Hsiao, C.-D.; Lee, A.Y.-L.; Ho, C.-S.; Liu, H.-L.; Wang, T.-J.; Jian, Y.-R.; Hsu, J.-C.; Huang, Z.-D.; Lee, T.-H.; et al. Mitigation of cerebellar neuropathy in globoid cell leukodystrophy mice by AAV-mediated gene therapy. Gene 2015, 571, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.S.; Kim, J.H.; Hawkins-Salsbury, J.A.; Macauley, S.L.; Tracy, E.T.; Vogler, C.A.; Han, X.; Song, S.K.; Wozniak, D.F.; Fowler, S.C.; et al. Bone marrow transplantation augments the effect of brain- and spinal cord-directed adeno-associated virus 2/5 gene therapy by altering inflammation in the murine model of globoid-cell leukodystrophy. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 9945–9957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, M.A.; Rao, H.Z.; Luzi, P.; Curtis, M.T.; Wenger, D.A. Extended normal life after AAVrh10-mediated gene therapy in the mouse model of Krabbe disease. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 2031–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, M.A.; Luzi, P.; Wenger, D.A. Can early treatment of twitcher mice with high dose AAVrh10-GALC eliminate the need for BMT? Bioimpacts 2021, 11, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M.S.; Issa, Y.; Jakubauskas, B.; Stoskute, M.; Elackattu, V.; Marshall, J.N.; Bogue, W.; Nguyen, D.; Hauck, Z.; Rue, E.; et al. Long-Term Improvement of Neurological Signs and Metabolic Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of Krabbe’s Disease after Global Gene Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Miller, C.A.; Shea, L.K.; Jiang, X.; Guzman, M.A.; Chandler, R.J.; Ramakrishnan, S.M.; Smith, S.N.; Venditti, C.P.; Vogler, C.A.; et al. Enhanced Efficacy and Increased Long-Term Toxicity of CNS-Directed, AAV-Based Combination Therapy for Krabbe Disease. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karumuthil-Melethil, S.; Marshall, M.S.; Heindel, C.; Jakubauskas, B.; Bongarzone, E.R.; Gray, S.J. Intrathecal administration of AAV/GALC vectors in 10–11-day-old twitcher mice improves survival and is enhanced by bone marrow transplant. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 94, 1138–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, M.J.; Gershenson, Z.T.; Giles, A.R.; Holzbaur, E.L.; Wolfe, J.H. Adeno-associated virus serotypes 1, 8, and 9 share conserved mechanisms for anterograde and retrograde axonal transport. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.I.; Tsukahara, N. Cerebrocerebellar communication systems. Physiol. Rev. 1974, 54, 957–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, R.L.; Krienen, F.M.; Castellanos, A.; Diaz, J.C.; Yeo, B.T.T. The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011, 106, 2322–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.R.; Habgood, M.D.; Dziegielewska, K.M. Barrier mechanisms in the brain, II. Immature brain. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1999, 26, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.J.; Marshall, M.S.; Issa, Y.; Marshall, J.N.; Nguyen, D.; Rue, E.; Pathmasiri, K.C.; Domowicz, M.S.; van Breemen, R.B.; Tai, L.M.; et al. Waning efficacy in a long-term AAV-mediated gene therapy study in the murine model of Krabbe disease. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 1883–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelvetri, L.C.; Givogri, M.I.; Zhu, H.; Smith, B.; Lopez-Rosas, A.; Qiu, X.; van Breemen, R.; Bongarzone, E.R. Axonopathy is a compounding factor in the pathogenesis of Krabbe disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 122, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti Castelvetri, L.; Givogri, M.I.; Hebert, A.; Smith, B.; Song, Y.; Kaminska, A.; Lopez-Rosas, A.; Morfini, G.; Pigino, G.; Sands, M.; et al. The sphingolipid psychosine inhibits fast axonal transport in Krabbe disease by activation of GSK3β and deregulation of molecular motors. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 10048–10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Zhu, H.; Givogri, M.I.; Chidavaenzi, R.L.; Lopez-Rosas, A.; Bongarzone, E.R. Psychosine induces the dephosphorylation of neurofilaments by deregulation of PP1 and PP2A phosphatases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 46, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, N.I.; Kreher, C.; Favret, J.; Nguyen, D.; Bongarzone, E.R.; Wrabetz, L.; Feltri, M.L.; Shin, D. Brainstem development requires galactosylceramidase and is critical for pathogenesis in a model of Krabbe disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | AAV Serotype | Postnatal Day | Route(s) & Sites | Vector Dose | Combination Therapy | Median Survival (Days) | Max. Survival (Days) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | AAV1 | P0-1 | i.c. (2 sites) i.c.v. | 3 × 1010 vg 3 × 1010 vg | None None | 55 55 | 66 66 | [28] |

| 2005 | AAV2 AAV5 | P3 P3 | i.c. (6 sites) i.c. (6 sites) | 4.4 × 108 vg 2.4 × 109 vg | None None | 47 52 | 57 62 | [17] |

| 2007 | AAV5 | P3 | i.c. (6 sites) | 2.4 × 109 vg | +BMT | 111 | 151 | [16] |

| 2011 | AAV5 | P3 | i.c. (6 sites) + i.t. | 1.6 × 1010 vg, i.c. 2 × 1010 vg, i.t. | +BMT | 71 123 | 78 282 | [31] |

| 2011 | AAV5 | P3 | i.c. (6 site) | 2.4 × 109 vg | None | 63 | 66 | [29] |

| 2012 | AAVrh10 | P2 | i.c. (1 sites) + i.c.v. + i.v. (P2) + i.v. (P7) | 1.5 × 109 vg, i.c. 3.25 × 109 vg, i.c.v. 7.6 × 109 vg, i.v. (P2) 7.6 × 109 vg, i.v. (P7) | None | 104 | 240 | [32] |

| 2015 | AAV5 | P3 | i.c. (6 sites) | 2.4 × 109 vg | None | 60 | 63 | [30] |

| 2016 | AAV9 AAVrh10 | P10-11 P10-11 | i.t. i.t. | 2 × 1011 vg 2 × 1011 vg | +BMT +BMT | 79 57 | 135 (Est.) 105 (Est.) | [36] |

| 2018 | AAV9 | P0–P1 | i.c. (5 sites) + i.t. + i.v. | 9 × 109 vg, i.c. 8.25 × 1010 vg, i.t. 3.3 × 1011 vg, i.v. | None +BMT | 263 284 | 484 675 | [34] |

| 2021 | AAVrh10 | P8-9 | i.v. i.v. i.v. i.v. | 4 × 1013 vg/kg 4 × 1013 vg/kg 1.6 × 1014 vg/kg 4 × 1014 vg/kg | None +BMT None None | 72 351 180 280 | 365 (Est.) 750 235 (Est.) 430 | [33] |

| 2021 | AAV9 | P0 | i.c. (6 sites) + i.t. | 1.2 × 1010 vg, i.c. 1.5 × 1010 vg, i.t. | None BMT BMT + SRT | 66.5 269 404 | 83 675 569 | [35] |

| 2025 | AAV9- | P3 | i.c. (4 sites) | 1.2 × 1012 vg, i.c. | None | 530 | 814 | Current study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, D.-S.; Ho, C.-S.; Huang, Y.-W.; Lee, T.-H.; Huang, Z.-D.; Wang, T.-J.; Cheng, W.-C.; Huang, S.-F. Durable Global Correction of CNS and PNS and Lifespan Rescue in Murine Globoid Cell Leukodystrophy via AAV9-Mediated Monotherapy. Cells 2025, 14, 1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241942

Lin D-S, Ho C-S, Huang Y-W, Lee T-H, Huang Z-D, Wang T-J, Cheng W-C, Huang S-F. Durable Global Correction of CNS and PNS and Lifespan Rescue in Murine Globoid Cell Leukodystrophy via AAV9-Mediated Monotherapy. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241942

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Dar-Shong, Che-Sheng Ho, Yu-Wen Huang, Tsung-Han Lee, Zo-Darr Huang, Tuan-Jen Wang, Wern-Cherng Cheng, and Sung-Fu Huang. 2025. "Durable Global Correction of CNS and PNS and Lifespan Rescue in Murine Globoid Cell Leukodystrophy via AAV9-Mediated Monotherapy" Cells 14, no. 24: 1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241942

APA StyleLin, D.-S., Ho, C.-S., Huang, Y.-W., Lee, T.-H., Huang, Z.-D., Wang, T.-J., Cheng, W.-C., & Huang, S.-F. (2025). Durable Global Correction of CNS and PNS and Lifespan Rescue in Murine Globoid Cell Leukodystrophy via AAV9-Mediated Monotherapy. Cells, 14(24), 1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241942

.png)