Alternative Splicing (AS) Provides an Alternative Mechanism for Regulating GLIS3 Expression and Activity

Highlights

- We identified a new isoform of the mouse Glis3 gene that is the predominant isoform in most tissues.

- We identified several potential mechanisms for the post-translational control of GLIS3.

- We identify different isoforms, post-translational modifications, and protein interactions for GLIS3 which offer mechanisms for regulating its activity and physiological processes, as well as its role in disease.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Intron–Exon Junctions in RNA-Seq Data

2.2. qRT-PCR Analysis

2.3. Expression Plasmids

2.4. Luciferase Assays

2.5. Stability Assays

2.6. Immunoprecipitation and Mass Spectrometry

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

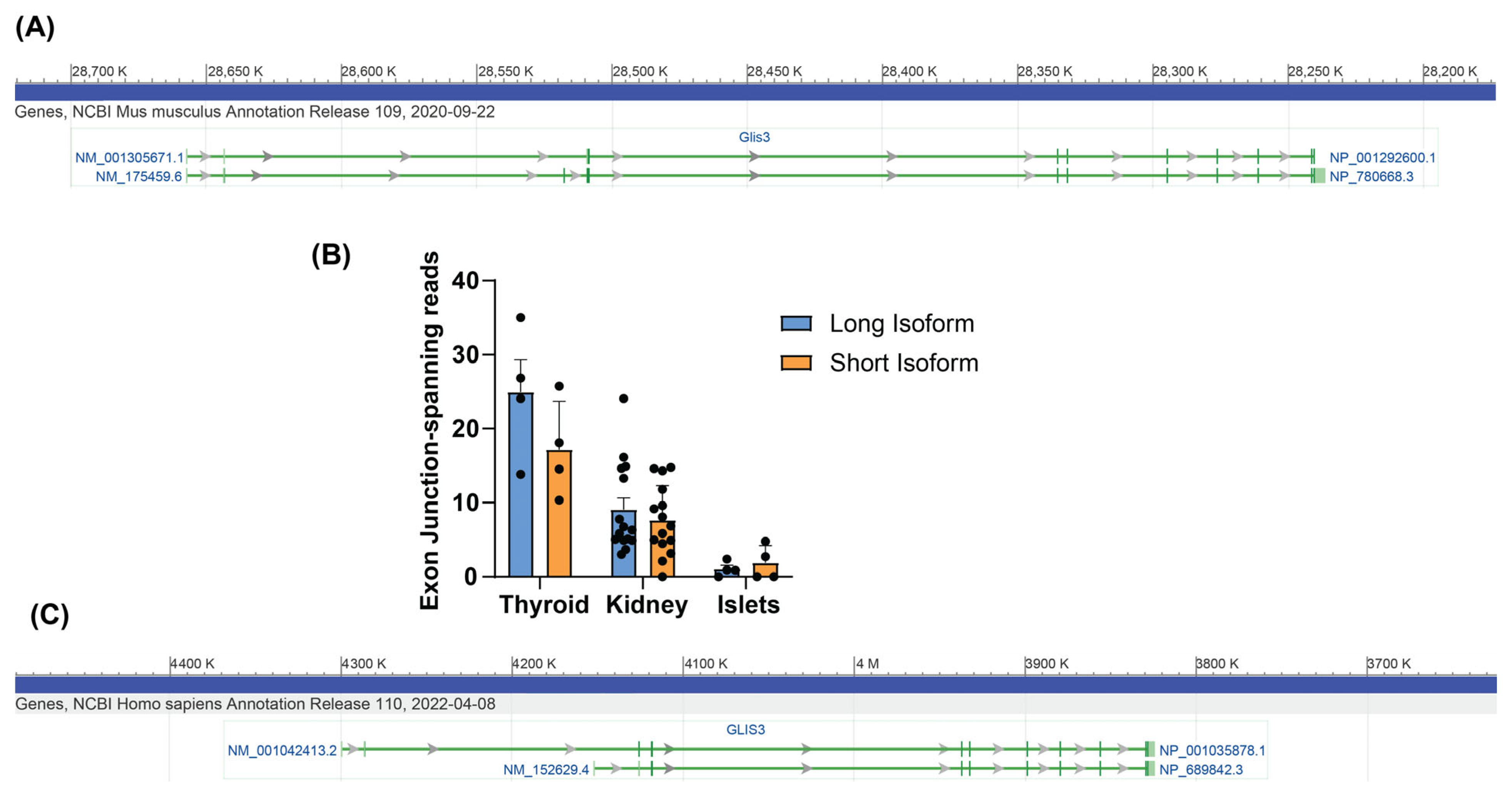

3.1. Identification of GLIS3 Isoforms in Mice and Humans

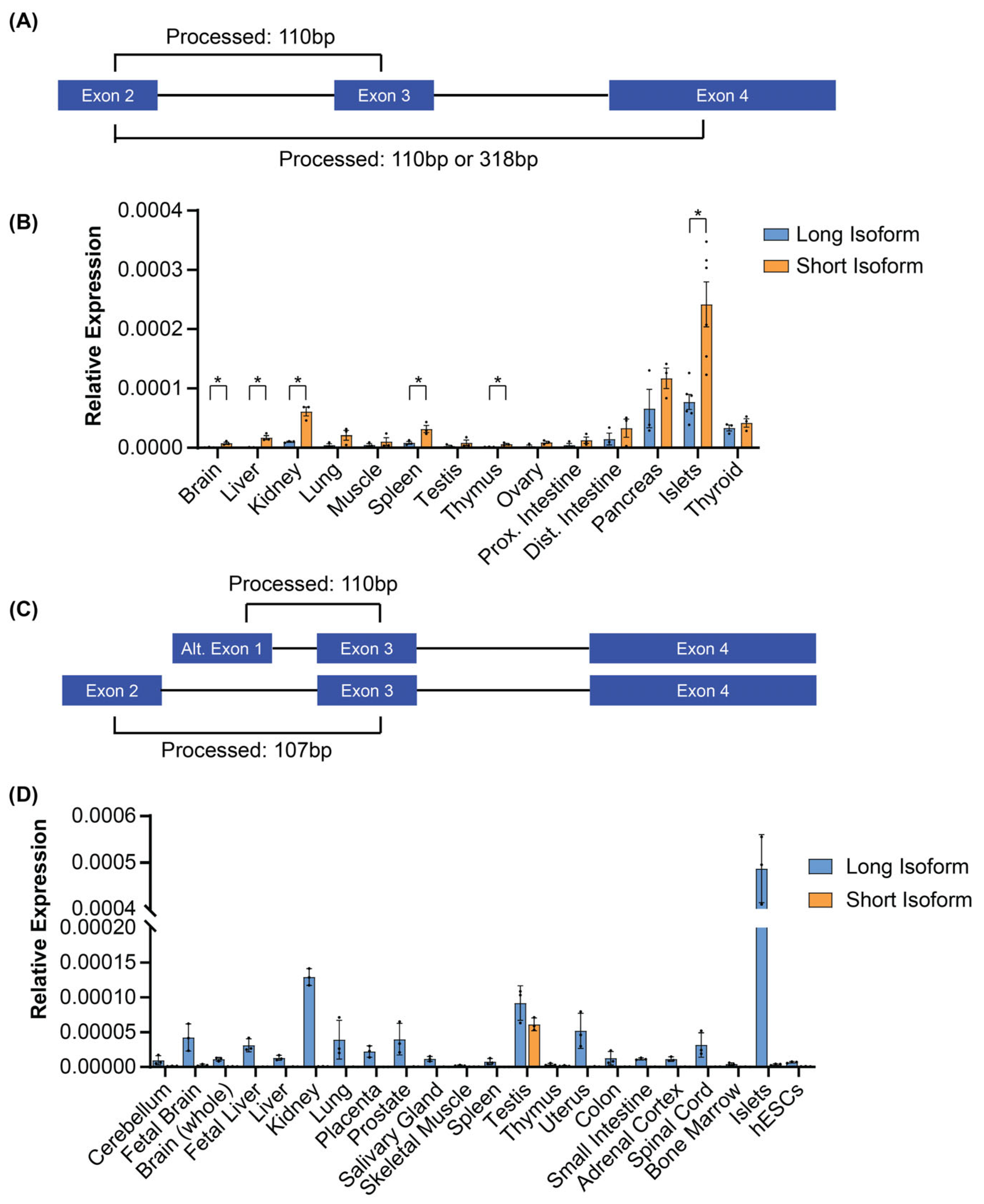

3.2. The Mouse Glis3 Short Isoform Is Expressed at Higher Levels than the Long Isoform

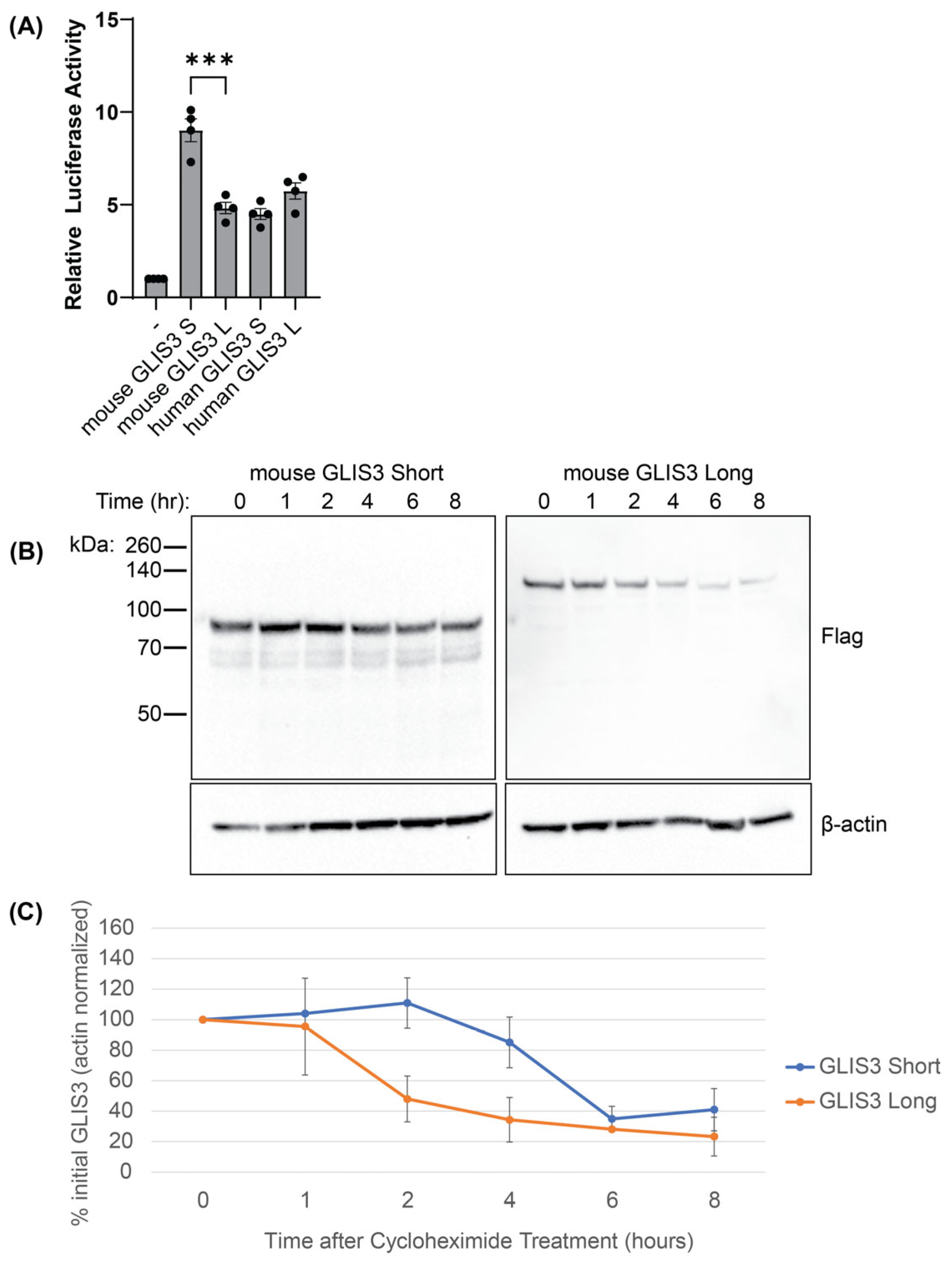

3.3. The Short Mouse Isoform of GLIS3 Exhibits Greater Activity and Stability

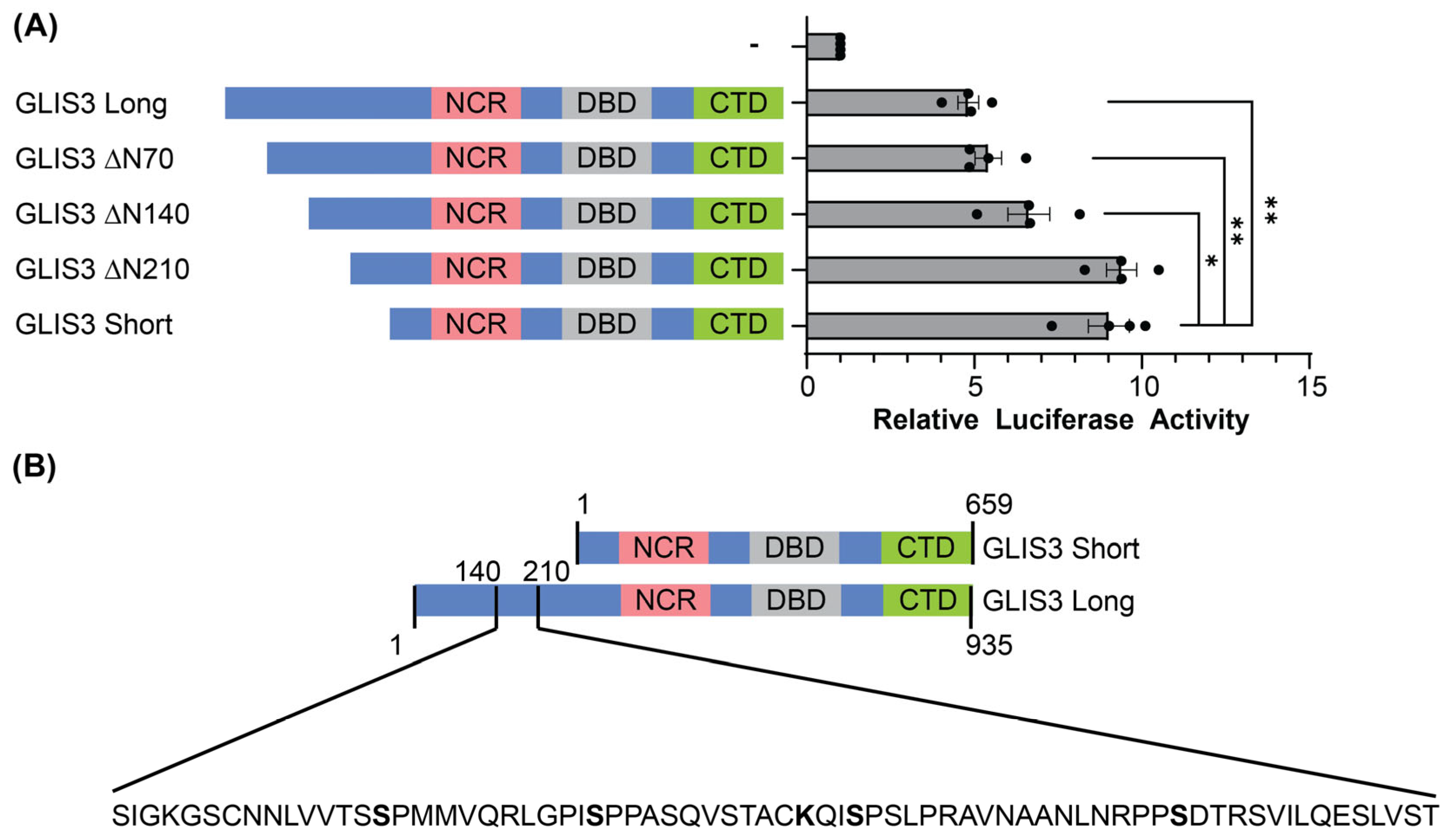

3.4. The N-Terminal Region Between 140 and 210 Is Responsible for the Difference in Activity Between GLIS3 Long and Short Isoforms

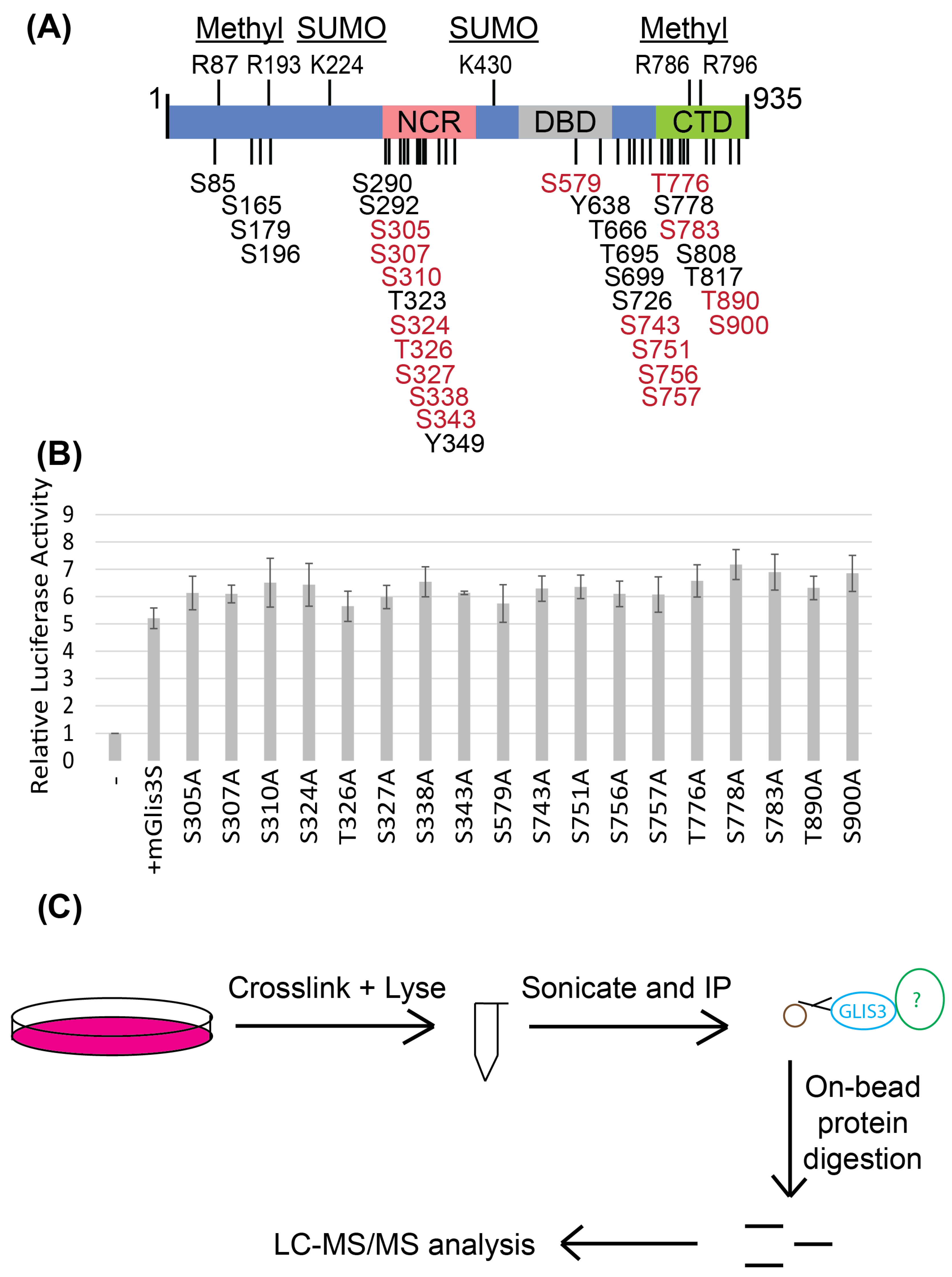

3.5. GLIS3 Is a Heavily Phosphorylated Protein and Interacts with Several Proteins

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Alternative Splicing |

| GLISBS | GLIS Binding Site |

References

- Kim, Y.S.; Nakanishi, G.; Lewandoski, M.; Jetten, A.M. GLIS3, a novel member of the GLIS subfamily of Kruppel-like zinc finger proteins with repressor and activation functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 5513–5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beak, J.Y.; Kang, H.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Jetten, A.M. Functional analysis of the zinc finger and activation domains of Glis3 and mutant Glis3(NDH1). Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 1690–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Beak, J.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Herbert, R.; Jetten, A.M. Glis3 is associated with primary cilia and Wwtr1/TAZ and implicated in polycystic kidney disease. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 2556–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kang, H.S.; Kim, Y.S.; ZeRuth, G.; Beak, J.Y.; Gerrish, K.; Kilic, G.; Sosa-Pineda, B.; Jensen, J.; Pierreux, C.E.; Lemaigre, F.P.; et al. Transcription factor Glis3, a novel critical player in the regulation of pancreatic beta-cell development and insulin gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 6366–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Hiramatsu, K.; Miyamoto, R.; Yasuda, K.; Suzuki, N.; Oshima, N.; Kiyonari, H.; Shiba, D.; Nishio, S.; Mochizuki, T.; et al. A murine model of neonatal diabetes mellitus in Glis3-deficient mice. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 2108–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chang, B.H.; Chan, L. Sustained expression of the transcription factor GLIS3 is required for normal beta cell function in adults. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, A.M. Emerging Roles of GLI-Similar Kruppel-like Zinc Finger Transcription Factors in Leukemia and Other Cancers. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Kumar, D.; Liao, G.; Lichti-Kaiser, K.; Gerrish, K.; Liao, X.H.; Refetoff, S.; Jothi, R.; Jetten, A.M. GLIS3 is indispensable for TSH/TSHR-dependent thyroid hormone biosynthesis and follicular cell proliferation. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 4326–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoville, D.W.; Kang, H.S.; Jetten, A.M. Transcription factor GLIS3: Critical roles in thyroid hormone biosynthesis, hypothyroidism, pancreatic beta cells and diabetes. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 215, 107632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senee, V.; Chelala, C.; Duchatelet, S.; Feng, D.; Blanc, H.; Cossec, J.C.; Charon, C.; Nicolino, M.; Boileau, P.; Cavener, D.R.; et al. Mutations in GLIS3 are responsible for a rare syndrome with neonatal diabetes mellitus and congenital hypothyroidism. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitri, P.; Warner, J.T.; Minton, J.A.; Patch, A.M.; Ellard, S.; Hattersley, A.T.; Barr, S.; Hawkes, D.; Wales, J.K.; Gregory, J.W. Novel GLIS3 mutations demonstrate an extended multisystem phenotype. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 164, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeb, A.M.; Al-Magamsi, M.S.; Eid, I.M.; Ali, M.I.; Hattersley, A.T.; Hussain, K.; Ellard, S. Incidence, genetics, and clinical phenotype of permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus in northwest Saudi Arabia. Pediatr. Diabetes 2012, 13, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitri, P.; Habeb, A.M.; Gurbuz, F.; Millward, A.; Wallis, S.; Moussa, K.; Akcay, T.; Taha, D.; Hogue, J.; Slavotinek, A.; et al. Expanding the Clinical Spectrum Associated with GLIS3 Mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E1362–E1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitri, P.; De Franco, E.; Habeb, A.M.; Gurbuz, F.; Moussa, K.; Taha, D.; Wales, J.K.; Hogue, J.; Slavotinek, A.; Shetty, A.; et al. An emerging, recognizable facial phenotype in association with mutations in GLI-similar 3 (GLIS3). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2016, 170, 1918–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, K.A.; Alsaedi, A.B.; Aljasser, A.; Altawil, A.; Kamal, N.M. Extended clinical features associated with novel Glis3 mutation: A case report. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2017, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Luo, S.; Long, X.; Li, Y.; She, S.; Hu, X.; Mo, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; He, C.; et al. Mutation screening of the GLIS3 gene in a cohort of 592 Chinese patients with congenital hypothyroidism. Clin. Chim. Acta 2018, 476, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralle, F.E.; Giudice, J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoville, D.; Lichti-Kaiser, K.; Grimm, S.; Jetten, A. GLIS3 binds pancreatic beta cell regulatory regions alongside other islet transcription factors. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 243, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Burnette, R.; Zhao, L.; Vanderford, N.L.; Poitout, V.; Hagman, D.K.; Henderson, E.; Ozcan, S.; Wadzinski, B.E.; Stein, R. The stability and transactivation potential of the mammalian MafA transcription factor are regulated by serine 65 phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoville, D.W.; Cyphert, H.A.; Liao, L.; Xu, J.; Reynolds, A.; Guo, S.; Stein, R. MLL3 and MLL4 Methyltransferases Bind to the MAFA and MAFB Transcription Factors to Regulate Islet beta-Cell Function. Diabetes 2015, 64, 3772–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.; Taylor, C.; Brown, G.D.; Papachristou, E.K.; Carroll, J.S.; D’Santos, C.S. Rapid immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry of endogenous proteins (RIME) for analysis of chromatin complexes. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trempus, C.S.; Papas, B.N.; Sifre, M.I.; Bortner, C.D.; Scappini, E.; Tucker, C.J.; Xu, X.; Johnson, K.L.; Deterding, L.J.; Williams, J.G.; et al. Functional Pdgfra fibroblast heterogeneity in normal and fibrotic mouse lung. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e164380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikom, D.; Zheng, S. Alternative splicing in neurodegenerative disease and the promise of RNA therapies. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandkar, M.R.; Shukla, S. Epigenetics and alternative splicing in cancer: Old enemies, new perspectives. Biochem. J. 2024, 481, 1497–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, S.M.; Rutter, G.A. Consequences for Pancreatic beta-Cell Identity and Function of Unregulated Transcript Processing. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 625235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZeRuth, G.T.; Williams, J.G.; Cole, Y.C.; Jetten, A.M. HECT E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Itch Functions as a Novel Negative Regulator of Gli-Similar 3 (Glis3) Transcriptional Activity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoard, T.M.; Yang, X.P.; Jetten, A.M.; ZeRuth, G.T. PIAS-family proteins negatively regulate Glis3 transactivation function through SUMO modification in pancreatic beta cells. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duma, D.; Jewell, C.M.; Cidlowski, J.A. Multiple glucocorticoid receptor isoforms and mechanisms of post-translational modification. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 102, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; D’Souza, R.C.; Tyanova, S.; Schaab, C.; Wisniewski, J.R.; Cox, J.; Mann, M. Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 1583–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Tian, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, V.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Investigation of receptor interacting protein (RIP3)-dependent protein phosphorylation by quantitative phosphoproteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, 1640–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttlin, E.L.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Elias, J.E.; Goswami, T.; Rad, R.; Beausoleil, S.A.; Villen, J.; Haas, W.; Sowa, M.E.; Gygi, S.P. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell 2010, 143, 1174–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, F.; Humphrey, S.J.; Cox, J.; Mischnik, M.; Schulte, A.; Klabunde, T.; Schafer, M.; Mann, M. Glucose-regulated and drug-perturbed phosphoproteome reveals molecular mechanisms controlling insulin secretion. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungewitter, E.K.; Rotgers, E.; Kang, H.S.; Lichti-Kaiser, K.; Li, L.; Grimm, S.A.; Jetten, A.M.; Yao, H.H. Loss of Glis3 causes dysregulation of retrotransposon silencing and germ cell demise in fetal mouse testis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Li, F. The Function of Pre-mRNA Alternative Splicing in Mammal Spermatogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hammaren, H.M.; Savitski, M.M.; Baek, S.H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Vanderford, N.L.; Stein, R. Phosphorylation within the MafA N terminus regulates C-terminal dimerization and DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 12655–12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmamaw, M.D.; He, A.; Zhang, L.R.; Liu, H.M.; Gao, Y. Histone deacetylase complexes: Structure, regulation and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, Y.; Kofman, E.R.; Almeida, M.; Ouyang, Z.; Ponte, F.; Mueller, J.R.; Cruz-Becerra, G.; Sakai, M.; Prohaska, T.A.; Spann, N.J.; et al. RANK ligand converts the NCoR/HDAC3 co-repressor to a PGC1β- and RNA-dependent co-activator of osteoclast gene expression. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 3421–3437.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scoville, D.W.; Grimm, S.A.; Williams, J.G.; Jetten, A.M. Alternative Splicing (AS) Provides an Alternative Mechanism for Regulating GLIS3 Expression and Activity. Cells 2025, 14, 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231912

Scoville DW, Grimm SA, Williams JG, Jetten AM. Alternative Splicing (AS) Provides an Alternative Mechanism for Regulating GLIS3 Expression and Activity. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231912

Chicago/Turabian StyleScoville, David W., Sara A. Grimm, Jason G. Williams, and Anton M. Jetten. 2025. "Alternative Splicing (AS) Provides an Alternative Mechanism for Regulating GLIS3 Expression and Activity" Cells 14, no. 23: 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231912

APA StyleScoville, D. W., Grimm, S. A., Williams, J. G., & Jetten, A. M. (2025). Alternative Splicing (AS) Provides an Alternative Mechanism for Regulating GLIS3 Expression and Activity. Cells, 14(23), 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231912