Role of the Ca2+-ATPase Pump (SERCA) in Capacitation and the Acrosome Reaction of Cryopreserved Bull Spermatozoa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Thawing of Cryopreserved Bovine Spermatozoa

2.2. Immunohistochemistry for the Detection of SERCA in Sperm Cells

2.3. Processing of Samples for Motility Assays, CTC, FIT-PSA, and Phalloidin Staining

2.4. Analysis of Motility

2.5. Analysis of Capacitation by Chlortetracycline (CTC) Staining

2.6. Evaluation of Acrosomal Reaction

2.7. Assessment of Actin Polymerisation

2.8. Assessment of Ca2+i

2.9. Complementary Eosin–Nigrosin Viability Assay

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

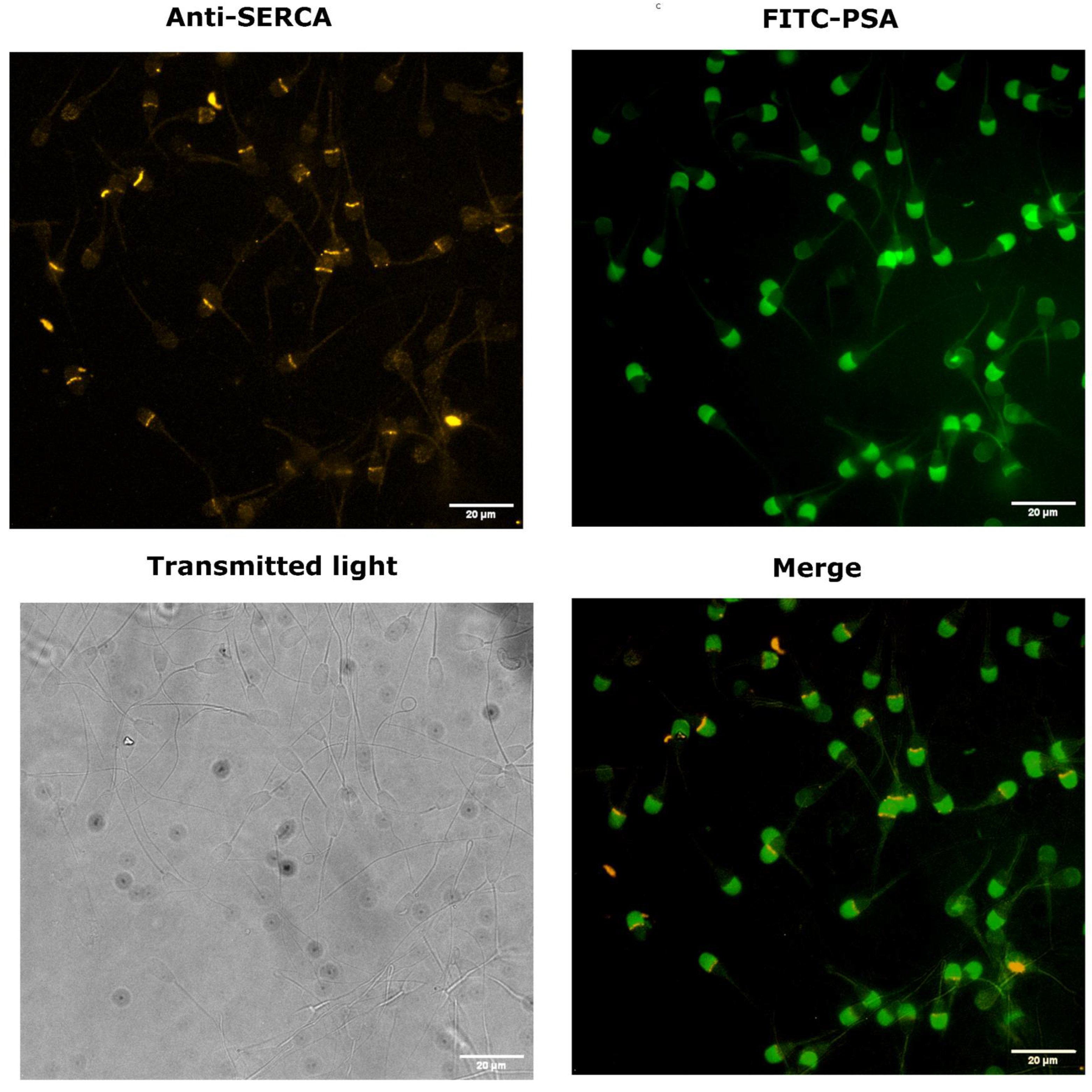

3.1. SERCA Is Concentrated in the Acrosomal Region in Cryopreserved Bull Sperm

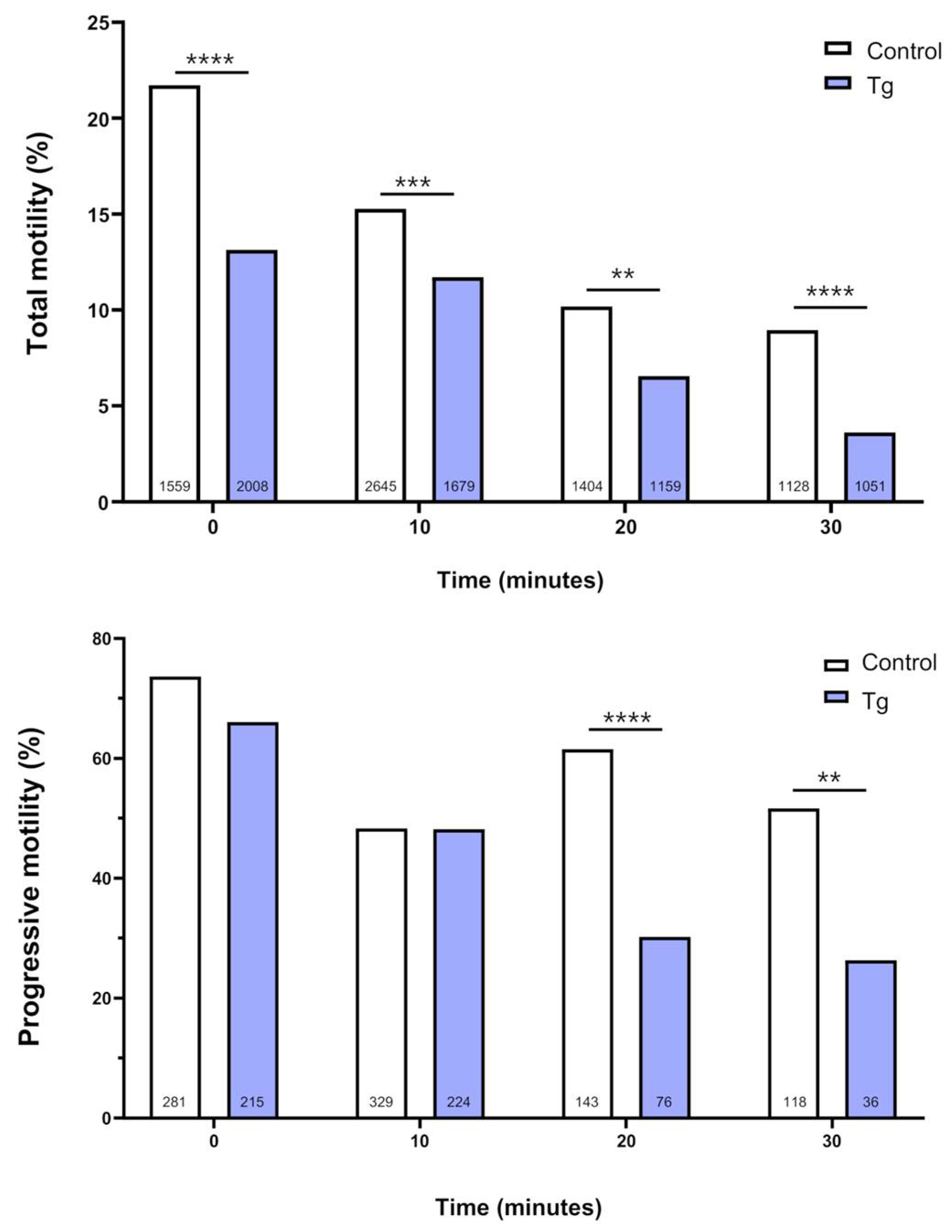

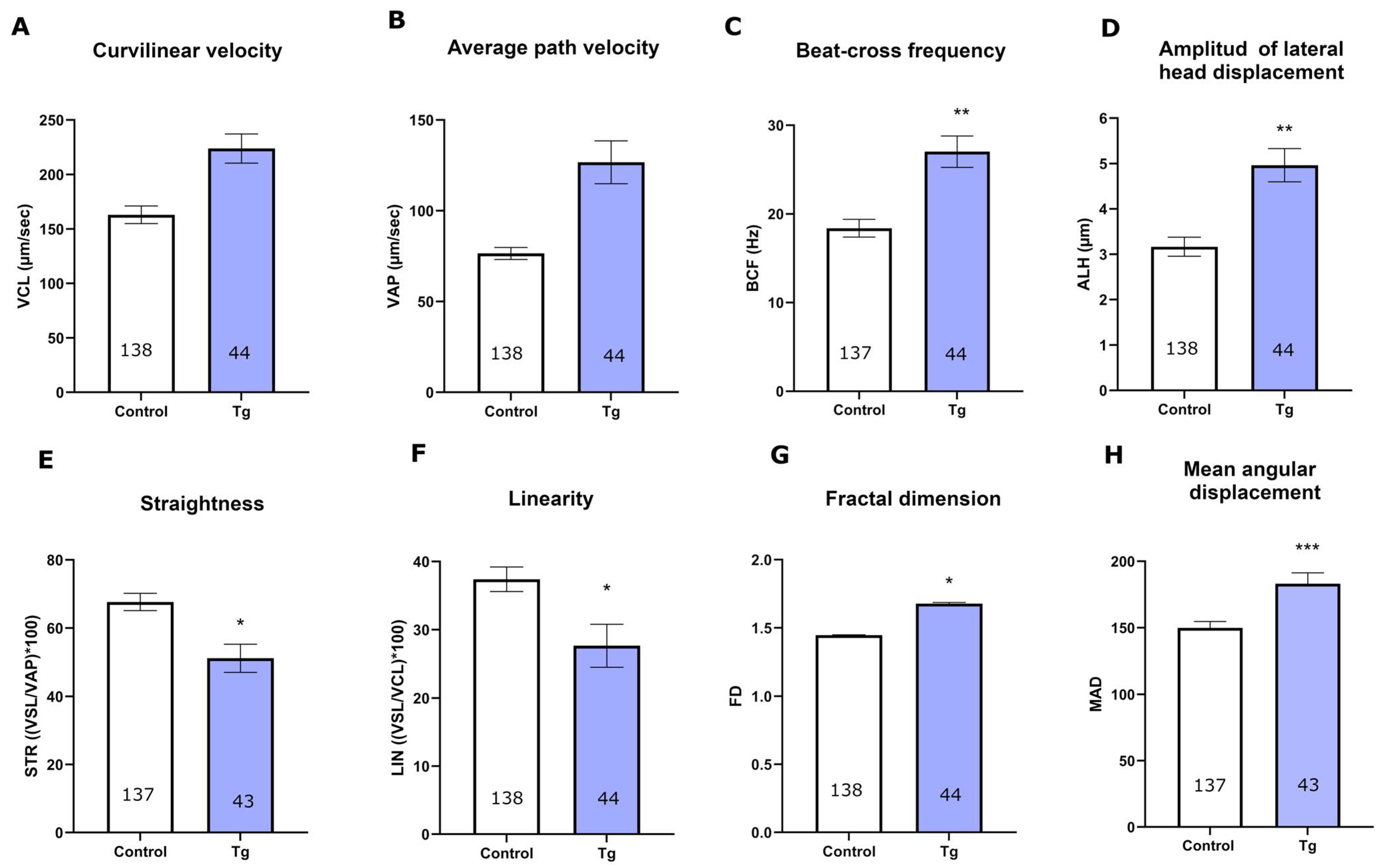

3.2. SERCA Inhibition Affects the Motility of Cryopreserved Bull Sperm

3.3. SERCA Plays a Key Role in the Progression of Capacitation in Bull Spermatozoa

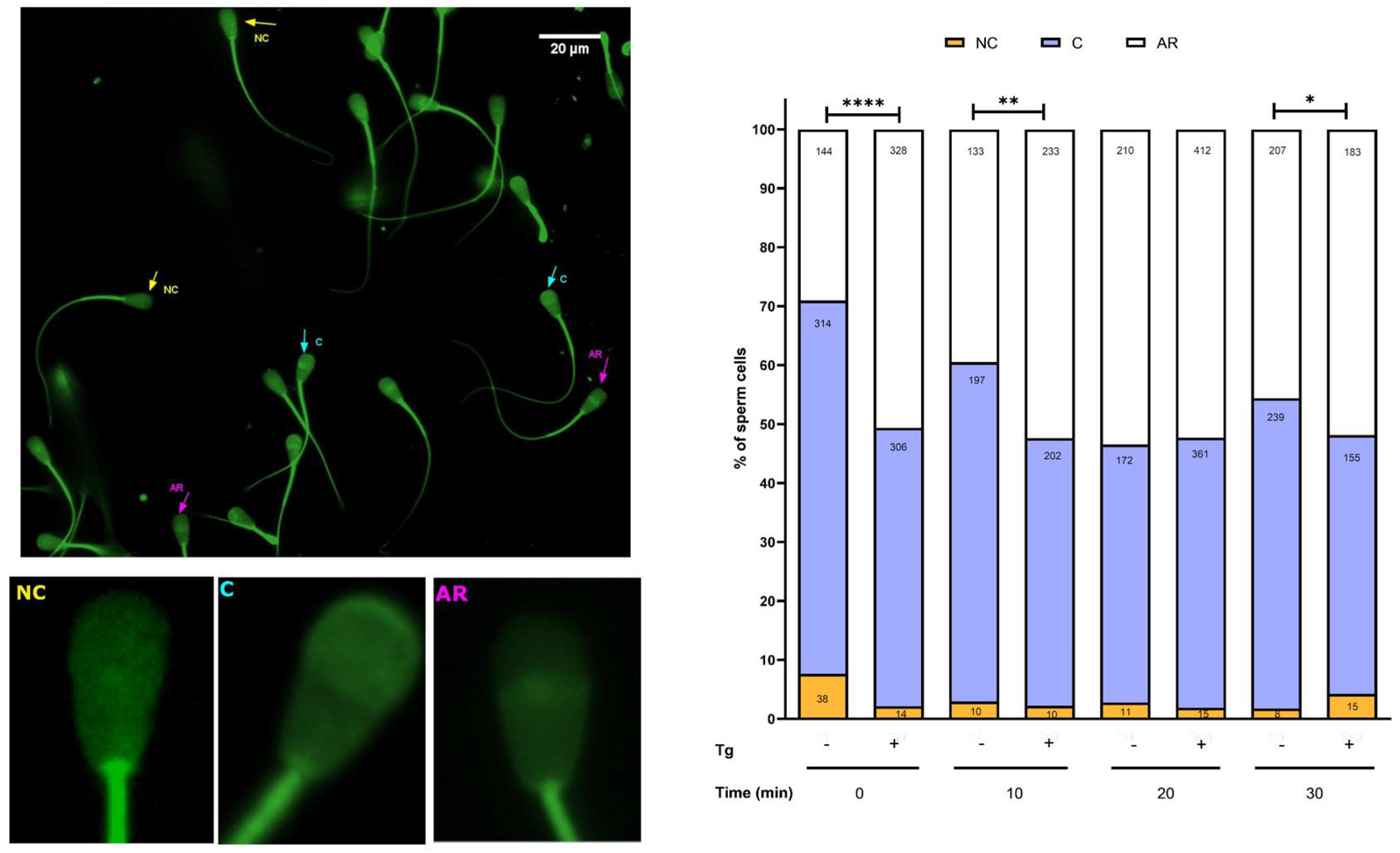

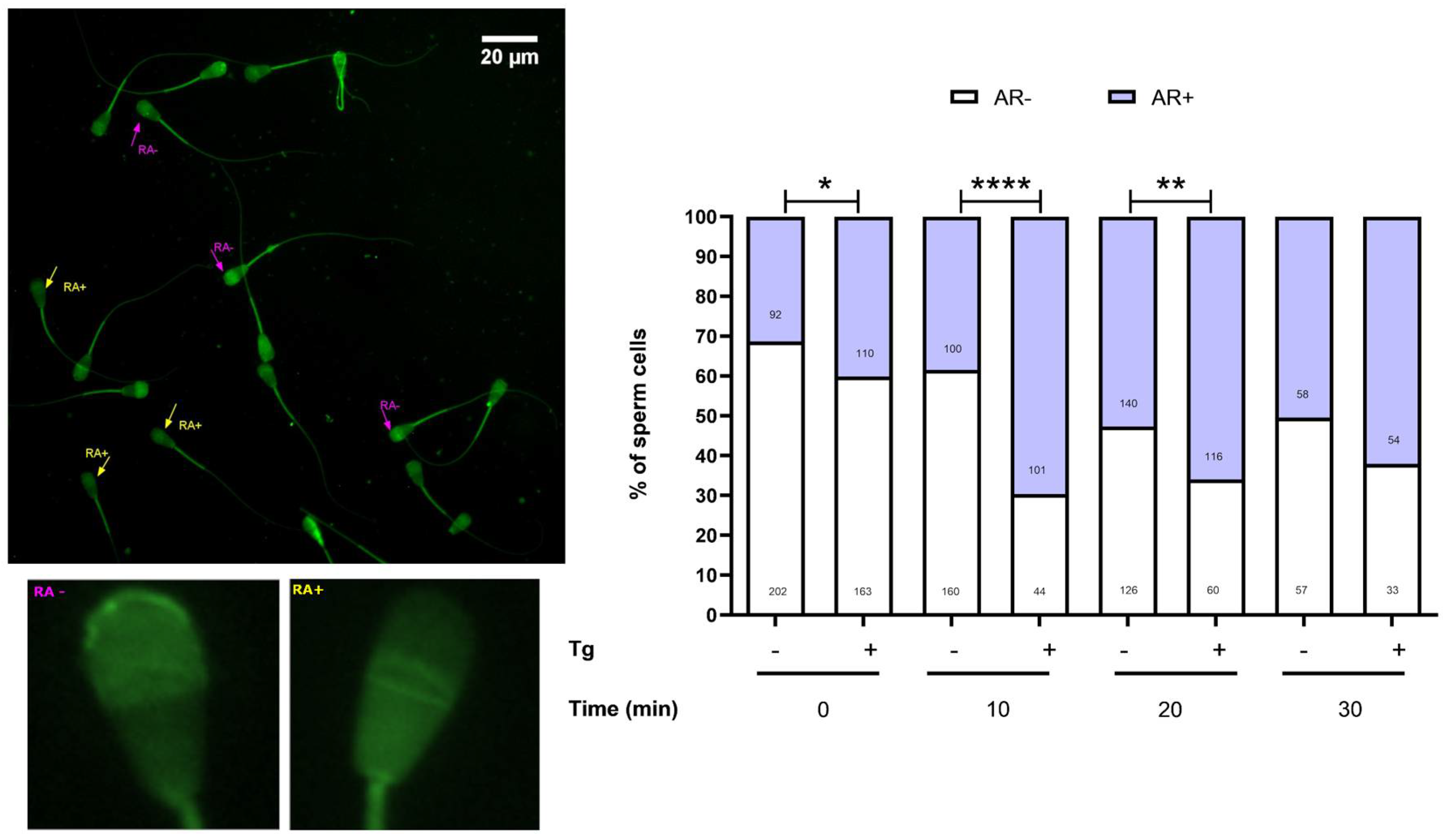

3.4. SERCA Activity Modulates the Acrosomal Reaction

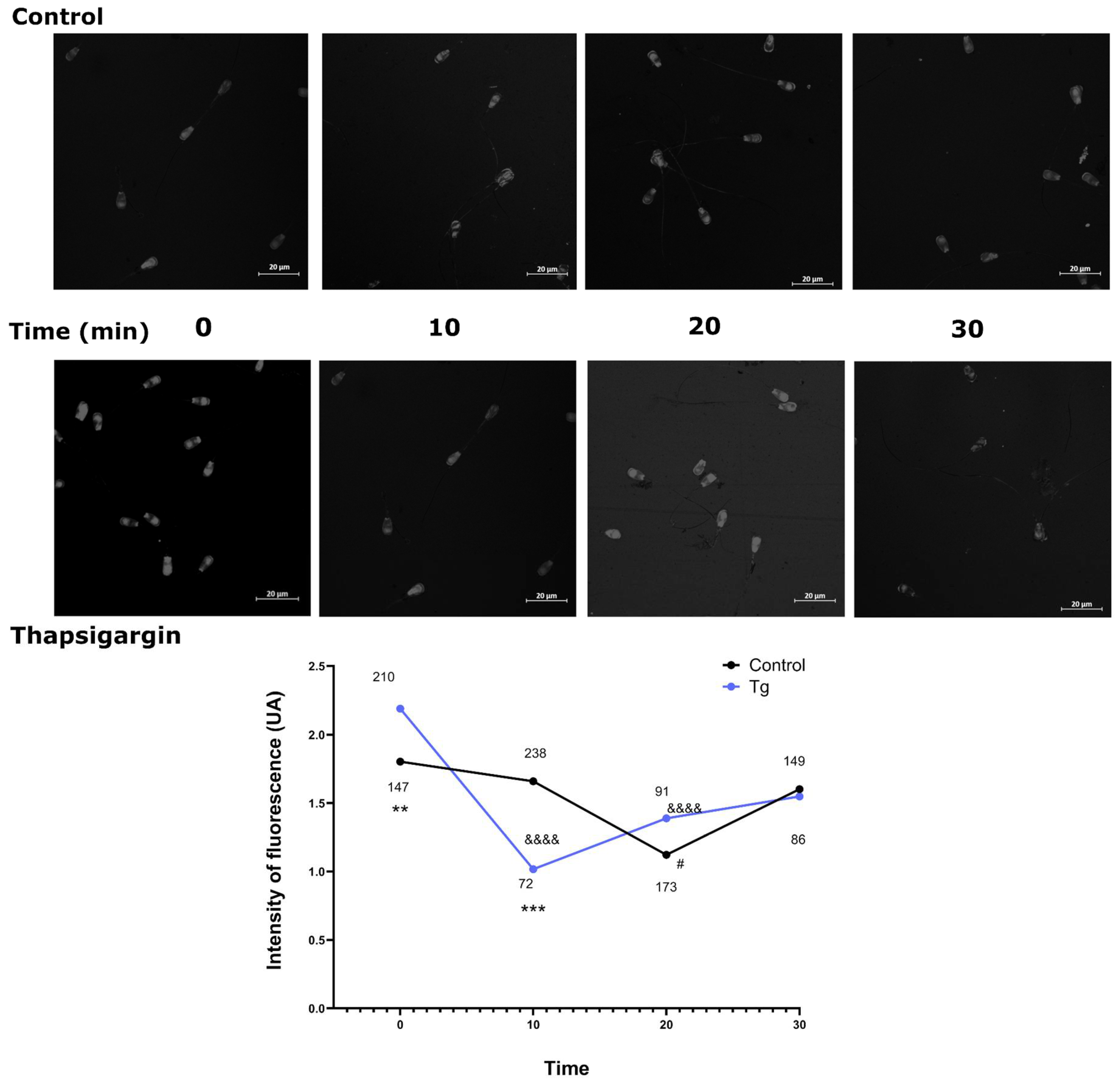

3.5. SERCA Inhibition Alters the Timeline of Actin Polymerisation

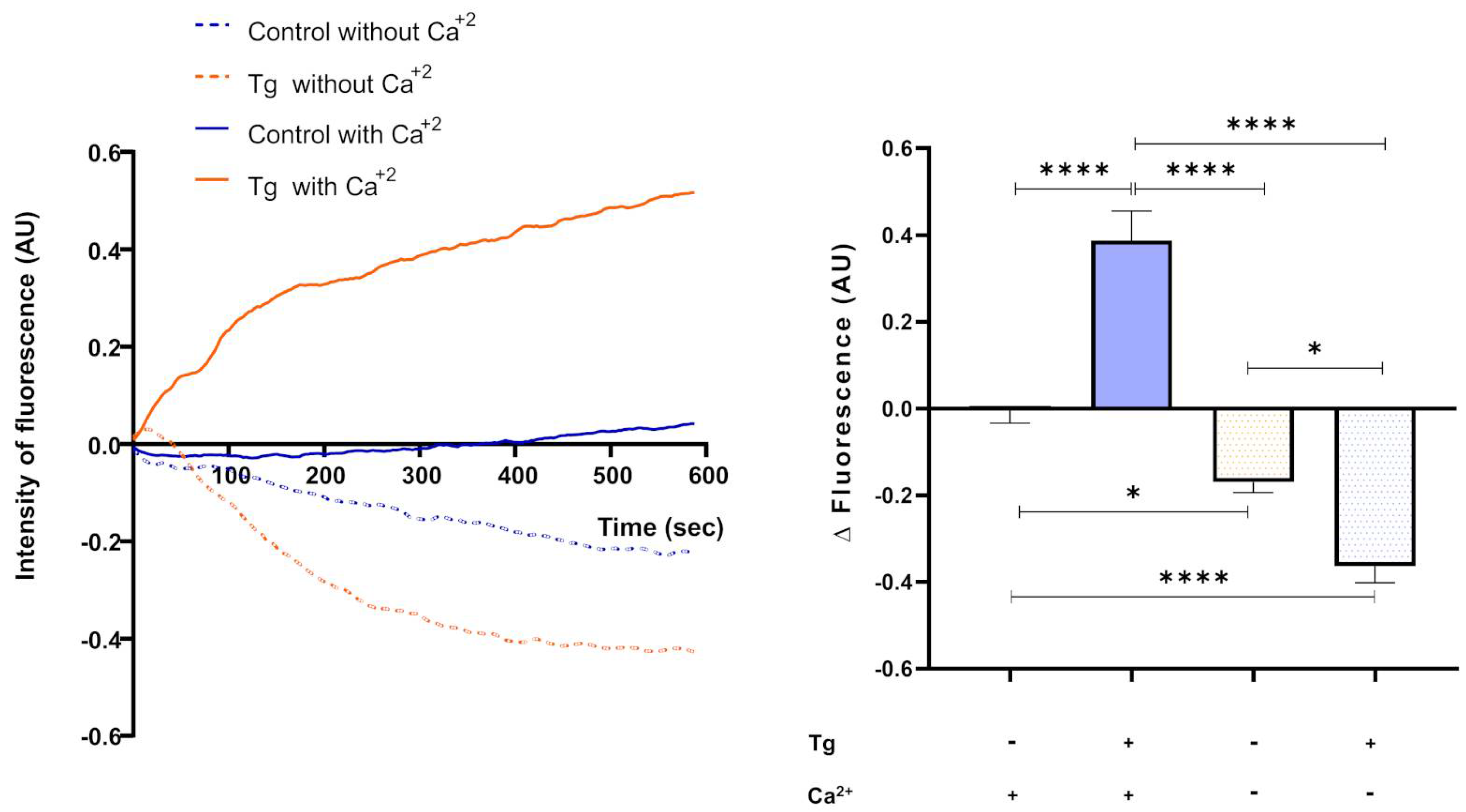

3.6. Thapsigargin-Sensitive Ca2+ Sequestration Modulates Intracellular Ca2+ Levels in Cryopreserved Bull Spermatozoa

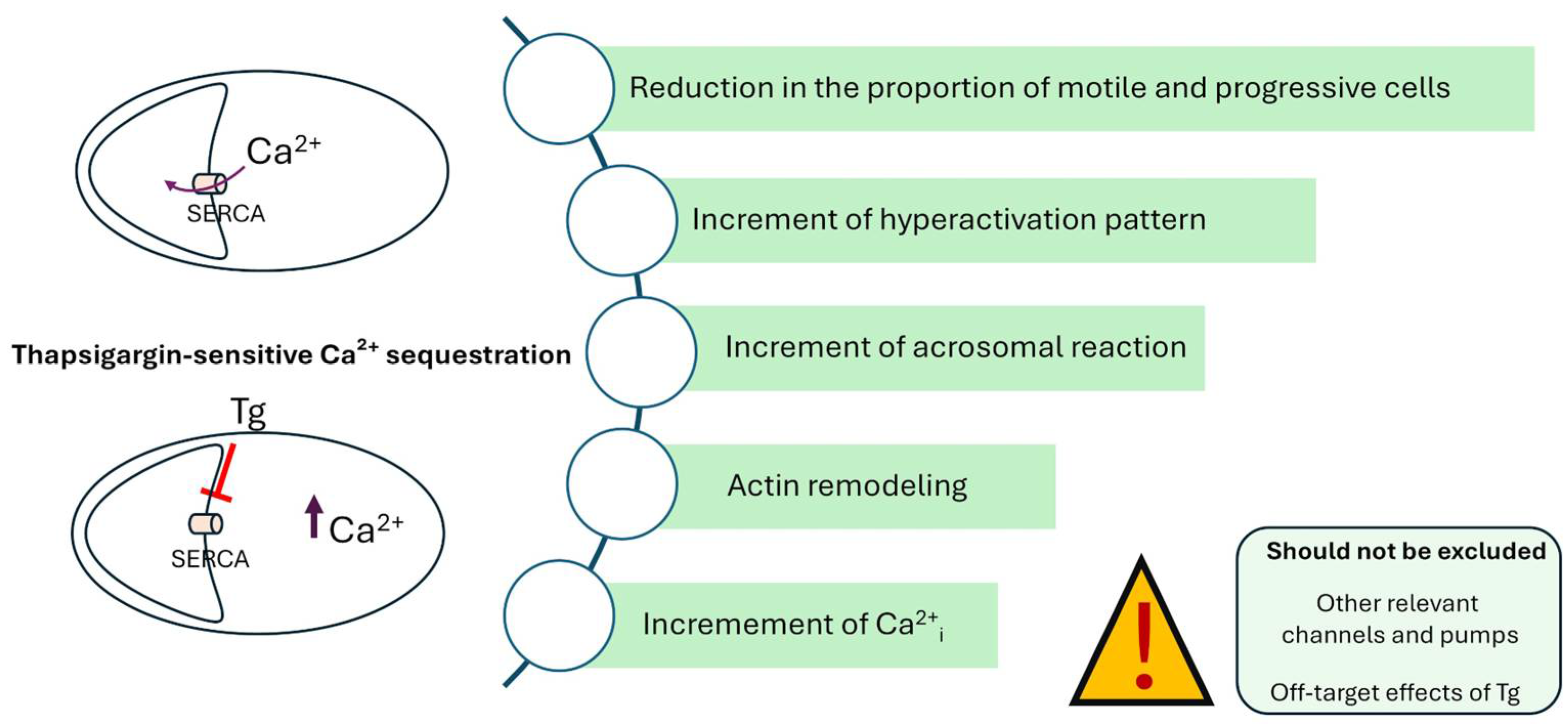

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SERCA | Ca2+-ATPase PUMP |

| Ca2+i | intracellular calcium |

| TALP | Tyrode’s albumin lactate pyruvate |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| TG | thapsigargin |

| PFA | paraformaldehyde |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| VSL | straight-line velocity |

| VCL | curvilinear velocity |

| VAP | average trajectory velocity |

| LIN | linearity |

| WOB | oscillation |

| STR | straightness |

| Mean ALH | mean head lateral displacement amplitude |

| Maximum ALH | maximum head lateral displacement amplitude |

| BCF | beat crossing frequency |

| DNC | dance |

| MAD | mean angular displacement |

| FD | fractal dimension |

| CTC | chlortetracycline |

| FITC-PSA | Fluorescein-labelled Pisum sativum agglutinin |

| F-actin | filament-like actin |

References

- Stival, C.; Puga Molina, L.D.C.; Paudel, B.; Buffone, M.G.; Visconti, P.E.; Krapf, D. Sperm Capacitation and Acrosome Reaction in Mammalian Sperm. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 2016, 220, 93–106. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27194351/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [PubMed]

- Florman, H.M.; Fissore, R.A. Fertilization in Mammals. In Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction: Two-Volume Set; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 149–196. [Google Scholar]

- Takei, G.L. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian sperm capacitation, and its regulation by sodium-dependent secondary active transporters. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2024, 23, e12614. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39416520/ (accessed on 19 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Breibart, H. Signaling pathways in sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2003, 49, 321–327. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12887084/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Buffone, M.G.; Ijiri, T.W.; Cao, W.; Merdiushev, T.; Aghajanian, H.K.; Gerton, G.L. Heads or tails? Structural events and molecular mechanisms that promote mammalian sperm acrosomal exocytosis and motility. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2012, 79, 4–18. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22031228/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.M.; Pavarotti, M.A.; Zanetti, M.N.; Zoppino, F.C.M.; De Blas, G.A.; Mayorga, L.S. Kinetics of human sperm acrosomal exocytosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 21, 244–254. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25452326/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, K.; Cartwright, E.J.; Jankevics, E.; Bundschu, K.; Liebermann, J.; Williams, J.C.; Armesilla, A.L.; Emerson, M.; Oceandy, D.; Knobeloch, K.P.; et al. Plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase 4 is required for sperm motility and male fertility. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 28220–28226. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15078889/ (accessed on 18 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Post, H.; Schwarz, A.; Brandenburger, T.; Aumüller, G.; Wilhelm, B. Arrangement of PMCA4 in bovine sperm membrane fractions. Int. J. Androl. 2010, 33, 775–783. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20050939/ (accessed on 18 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.P.; English, A.M.; Cronin, S.; Hoey, D.A.; Meade, K.G.; Fair, S. Genomic identification, expression profiling, and functional characterization of CatSper channels in the bovine. Biol. Reprod. 2017, 97, 302–312. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29044427/ (accessed on 18 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.; Dorval, V.; Goupil, S.; Leclerc, P. Identification and localisation of SERCA 2 isoforms in mammalian sperm. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 13, 307–316. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17376796/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.; Michelangeli, F.; Publicover, S. Regulation and roles of Ca2+ stores in human sperm. Reproduction 2015, 150, R65–R76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garriga, F.; Martínez-Hernández, J.; Parra-Balaguer, A.; Llavanera, M.; Yeste, M. The Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) is present in pig sperm and modulates their physiology over liquid preservation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4184. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39905176/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kumar, S.; Lessard, C.; Bailey, J.L. ACRBP (Sp32) is involved in priming sperm for the acrosome reaction and the binding of sperm to the zona pellucida in a porcine model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251973. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34086710/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervasi, M.G.; Xu, X.; Carbajal-Gonzalez, B.; Buffone, M.G.; Visconti, P.E.; Krapf, D. The actin cytoskeleton of the mouse sperm flagellum is organized in a helical structure. J. Cell. Sci. 2018, 131, jcs215897. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29739876/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Breitbart, H.; Cohen, G.; Rubinstein, S. Role of actin cytoskeleton in mammalian sperm capacitation and the acrosome reaction. Reproduction 2005, 129, 263–268. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15749953/ (accessed on 19 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Romarowski, A.; Luque, G.M.; La Spina, F.A.; Krapf, D.; Buffone, M.G. Role of Actin Cytoskeleton During Mammalian Sperm Acrosomal Exocytosis. In Sperm Acrosome Biogenesis and Function During Fertilization. Advances in Anatomy, Embryology and Cell Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 220, pp. 129–144. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27194353/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Breitbart, H.; Finkelstein, M. Actin cytoskeleton and sperm function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 506, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, E.; Rubinstein, S.; Cohen, G.; Shternall, K.; Rivlin, J.; Breitbart, H. Remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton during mammalian sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 68, 837–845. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12604633/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Benko, F.; Mohammadi-Sangcheshmeh, A.; Ďuračka, M.; Lukáč, N.; Tvrdá, E. In vitro versus cryo-induced capacitation of bovine spermatozoa, part 1: Structural, functional, and oxidative similarities and differences. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276683. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36269791/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pons-Rejraji, H.; Bailey, J.L.; Leclerc, P. Cryopreservation affects bovine sperm intracellular parameters associated with capacitation and acrosome exocytosis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2009, 21, 525–537. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19383259/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.C.; Suarez, S.S. An inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-gated intracellular Ca(2+) store is involved in regulating sperm hyperactivated motility. Biol. Reprod. 2001, 65, 1606–1615. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11673282/ (accessed on 14 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarante, N.; Alonso, C.A.I.; Plaza, J.; Lottero-Leconte, R.; Arroyo-Salvo, C.; Yaneff, A.; Osycka-Salut, C.E.; Davio, C.; Miragaya, M.; Perez-Martinez, S. Cyclic AMP efflux through MRP4 regulates actin dynamics signalling pathway and sperm motility in bovines. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–14. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32973195/ (accessed on 19 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.M.; Ford, W.C.L. Effects of Ca-ATPase inhibitors on the intracellular calcium activity and motility of human spermatozoa. Int. J. Androl. 2003, 26, 366–375. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14636222/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Duritahala Sakase, M.; Harayama, H. Involvement of Ca2+-ATPase in suppressing the appearance of bovine helically motile spermatozoa with intense force prior to cryopreservation. J. Reprod. Dev. 2022, 68, 181–189. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35236801/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alquézar-Baeta, C.; Gimeno-Martos, S.; Miguel-Jiménez, S.; Santolaria, P.; Yániz, J.; Palacín, I.; Casao, A.; Cebrián-Pérez, J.Á.; Muiño-Blanco, T.; Pérez-Pé, R. OpenCASA: A new open-source and scalable tool for sperm quality analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006691. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30657753/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.X.; Roldan, E.R.S. Bicarbonate/CO2 is not required for zona pellucida- or progesterone- induced acrosomal exocytosis of mouse spermatozoa but is essential for capacitation. Biol. Reprod. 1995, 52, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabtay, O.; Breitbart, H. CaMKII prevents spontaneous acrosomal exocytosis in sperm through induction of actin polymerization. Dev. Biol. 2016, 415, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Gupta, S.; Sharma, R. Eosin-Nigrosin Staining Procedure. In Andrological Evaluation of Male Infertility: A Laboratory Guide; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 73–77. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-26797-5_8 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- DasGupta, S.; Mills, C.L.; Fraser, L.R. Ca(2+)-related changes in the capacitation state of human spermatozoa assessed by a chlortetracycline fluorescence assay. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1993, 99, 135–143. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8283430/ (accessed on 18 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fraser, L.R.; Abeydeera, L.R.; Niwa, K. Ca(2+)-regulating mechanisms that modulate bull sperm capacitation and acrosomal exocytosis as determined by chlortetracycline analysis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 40, 233–241. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7766417/ (accessed on 18 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, T.; Takahashi, K.; Kanasaki, H.; Miyazaki, K. Evaluation of acrosome reaction and viability of human sperm with two fluorescent dyes. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2002, 266, 114–117. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12049293/ (accessed on 18 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Montoya, F.; Bribiesca-Sánchez, A.; Hernández-Herrera, P.; Díaz-Guerrero, D.S.; Gonzalez-Cota, A.L.; Bloomfield-Gadelha, H.; Darszon, A.; Corkidi, G. 3D+t Multifocal Imaging Dataset of Human Sperm. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1–7. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-025-05177-4 (accessed on 17 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ugur, M.R.; Saber Abdelrahman, A.; Evans, H.C.; Gilmore, A.A.; Hitit, M.; Arifiantini, R.I.; Purwantara, B.; Kaya, A.; Memili, E. Advances in Cryopreservation of Bull Sperm. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 458154. Available online: www.frontiersin.org (accessed on 19 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Costello, S.; Michelangeli, F.; Nash, K.; Lefievre, L.; Morris, J.; Machado-Oliveira, G.; Barratt, C.; Kirkman-Brown, J.; Publicover, S. Ca2+-stores in sperm: Their identities and functions. Reproduction 2009, 138, 425–437. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19542252/ (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cárdenas, C.; Romarowski, A.; Orta, G.; De la Vega-Beltrán, J.L.; Martín-Hidalgo, D.; Hernández-Cruz, A.; Visconti, P.E.; Darszon, A. Starvation induces an increase in intracellular calcium and potentiates the progesterone-induced mouse sperm acrosome reaction. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21528. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8441833/ (accessed on 17 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.; Wootton, L.; Michelangeli, F.; Lefièvre, L.; Barratt, C.; Publicover, S. Secretory pathway Ca(2+)-ATPase (SPCA1) Ca(2)+ pumps, not SERCAs, regulate complex [Ca(2+)](i) signals in human spermatozoa. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 1673–1685. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15811949/ (accessed on 18 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, K.H.; Zheng, M.H.; Steer, J.H.; Giardina, T.M.; Han, R.; Lo, S.Z.; Bakker, A.J.; Cassady, A.I.; A Joyce, D.; Xu, J. Thapsigargin modulates osteoclastogenesis through the regulation of RANKL-induced signaling pathways and reactive oxygen species production. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005, 20, 1462–1471. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16007343/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Fan, C.; Yang, Y.; Di, S.; Hu, W.; Li, T.; Zhu, Y.; Han, J.; Xin, Z.; Wu, G.; et al. Thapsigargin sensitizes human esophageal cancer to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via AMPK activation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35196. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/srep35196 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, T.; Tang, S.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Deng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, X. Thapsigargin induces apoptosis when autophagy is inhibited in HepG2 cells and both processes are regulated by ROS-dependent pathway. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 41, 167–179. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S138266891530137X (accessed on 12 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Gonzalez, C.; Michelangeli, F.; Harper, C.V.; Barratt, C.L.R.; Publicover, S.J. Calcium signalling in human spermatozoa: A specialized “toolkit” of channels, transporters and stores. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2006, 12, 253–267. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16338990/ (accessed on 14 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.-H.; Kim, B.-J.; Kang, J.; Nam, T.-S.; Lim, J.M.; Kim, H.T.; Park, J.K.; Kim, Y.G.; Chae, S.-W.; Kim, U.-H. Ca2+ signaling tools acquired from prostasomes are required for progesterone-induced sperm motility. Sci. Signal. 2011, 4, ra31. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21586728/ (accessed on 14 October 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez, M.A.; Orlowski, A.; Portiansky, E.L.; Ferrero, P. Role of the Ca2+-ATPase Pump (SERCA) in Capacitation and the Acrosome Reaction of Cryopreserved Bull Spermatozoa. Cells 2025, 14, 1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231892

Rodríguez MA, Orlowski A, Portiansky EL, Ferrero P. Role of the Ca2+-ATPase Pump (SERCA) in Capacitation and the Acrosome Reaction of Cryopreserved Bull Spermatozoa. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231892

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez, Maia A., Alejandro Orlowski, Enrique L. Portiansky, and Paola Ferrero. 2025. "Role of the Ca2+-ATPase Pump (SERCA) in Capacitation and the Acrosome Reaction of Cryopreserved Bull Spermatozoa" Cells 14, no. 23: 1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231892

APA StyleRodríguez, M. A., Orlowski, A., Portiansky, E. L., & Ferrero, P. (2025). Role of the Ca2+-ATPase Pump (SERCA) in Capacitation and the Acrosome Reaction of Cryopreserved Bull Spermatozoa. Cells, 14(23), 1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231892