Preventing Skeletal-Related Events in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma

Abstract

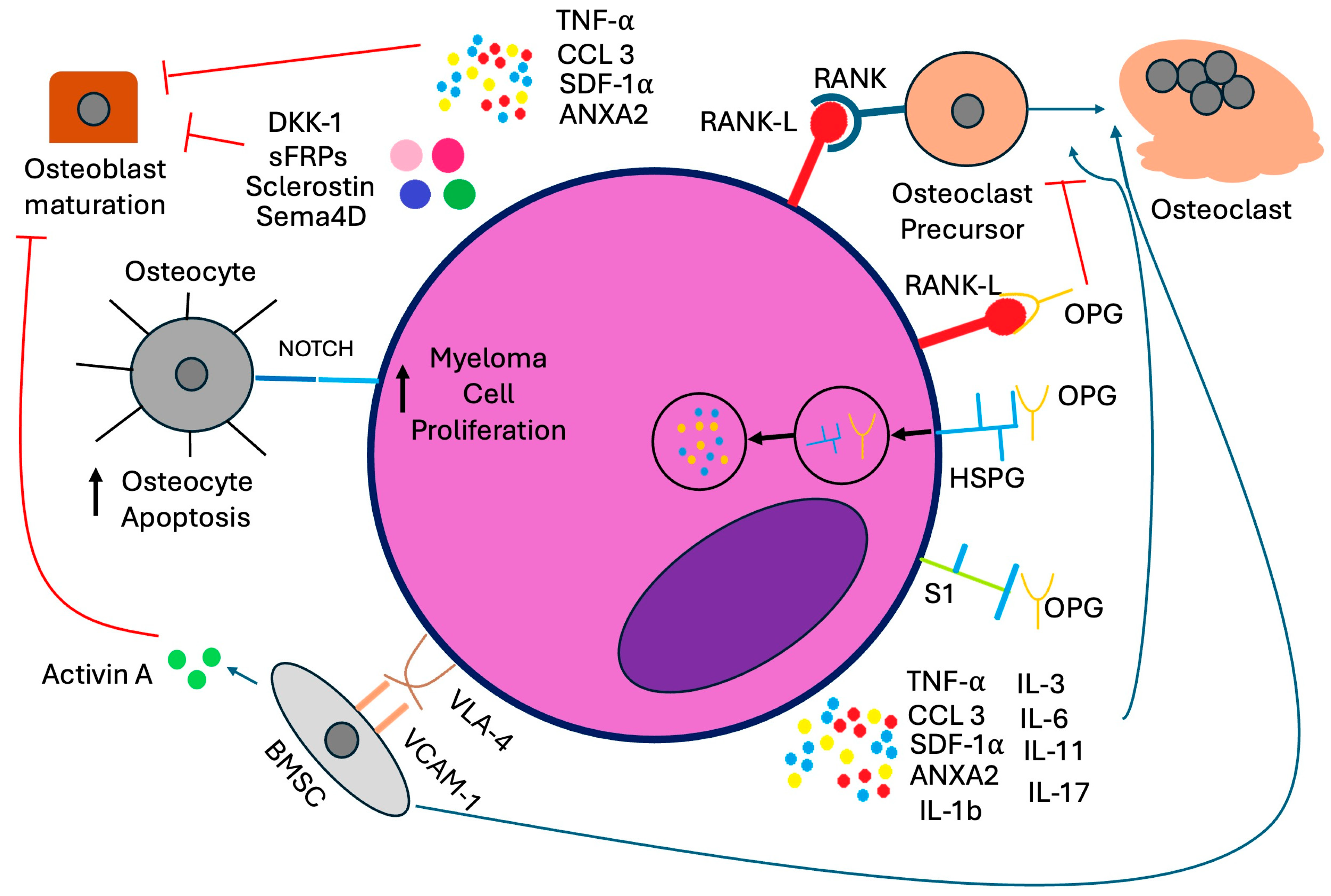

1. Introduction

2. Bone-Modifying Agents: Bisphosphonates and RANKL Inhibitors

2.1. Bisphosphonates

| Mechanism of Action | Route of Administration and Schedule | Pharmacokinetics | Reduction in Skeletal-Related Events | Progression-Free and Overall Survival Benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clodronate | A non-nitrogen-containing (first-generation) bisphosphonate that incorporates into adenosine triphosphate (ATP) after osteoclast-mediated uptake from the bone mineral surface, leading to osteoclast apoptosis [17]. | 1600 mg by mouth daily indefinitely or until progression of osteolytic lesions or hypercalcemia not responsive to fluids and chemotherapy [20]. | Half-life elimination of 4–8 h in animal models Renal elimination Contraindicated if serum creatinine is over 5 mg/dL If CrCl is 30–50, administer 75% of normal oral dose If CrCl is <30, administer 50% of normal oral dose No dose adjustment for hepatic impairment [21] | Significant reduction in progression of osteolytic bone lesions compared to placebo [22]. | No statistically significant survival benefit observed with MM-specific mortality. PFS not examined [20]. |

| Pamidronate | A nitrogen-containing (second-generation) bisphosphonate that incorporates into bone and inhibits farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase in osteoclasts after endocytosis, which regulates production of sterols and lipids critical for osteoclast cellular activities, ultimately leading to apoptosis [17]. | 30 mg of intravenous pamidronate monthly for at least three years [23]. | Half-life elimination of 28 +/− 7 h If CrCl < 30 or Cr > 3, consider a longer infusion time of 30 mg over 4–6 h Avoid use and consider alternative agents in dialysis patients Withhold therapy for kidney function deterioration without apparent cause, resume when kidney function returns to within 10% of baseline No dose adjustment for hepatic impairment [22,24] | Significant reduction in skeletal-related events in patients with both newly diagnosed and relapsed MM compared to placebo. This benefit was only observed with intravenous administration, not oral administration [25,26,27]. | No statistically significant overall survival benefit observed. PFS not examined [25]. |

| Zoledronic Acid | Same as pamidronate, but 100 times as potent [17]. Additionally, has in vitro direct anti-tumor effects by down-regulating IL-6 secretion and reducing CD40, CD49d, CD54, and CD106 expression [19]. | 4 mg of intravenous zoledronic acid every four weeks for two years [28]. | Half-life elimination of 146 h If CrCl is 50–60, reduce dose to 3.5 mg If CrCl is 40–50, reduce dose to 3.3 mg If CrCl is 30–40, reduce dose to 3 mg Use not recommended for CrCl < 30 or if patient is on dialysis No dose adjustment for hepatic impairment [29,30] | Lower rates of skeletal-related events when compared to clodronate [3]. | Reduced mortality by 16% (95% CI 4–26%) and extended median overall survival by 5.5 months (p = 0.04) compared to clodronate. Improved progression-free survival compared to clodronate by 12% (95% CI 2–20%) [3]. |

| Denosumab | Human monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes RANKL, inhibiting osteoclast maturation and bone resorption [31]. Shown in murine models to reduce serum paraprotein levels [32]. In contrast to bisphosphonates, denosumab is not incorporated into bone and thus its effect on bone resorption rapidly declines upon treatment discontinuation [33,34,35]. | 120 mg of subcutaneous denosumab every four weeks for two years [36,37]. | Half-life elimination is 25.4 days No dosage adjustment necessary for CrCl < 30, monitor closely for hypocalcemia No dose adjustment for hepatic impairment [38] | Denosumab superior regarding time to first skeletal-related event when compared to zoledronic acid after two years of treatment [36]. | Overall survival is similar to zoledronic acid, but a progression-free survival benefit was found in patients intended to undergo autologous stem cell transplant (46.1 months vs. 35.7 months, HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.49–0.85, p = 0.002) [37]. |

2.2. Clodronate

2.3. Pamidronate

2.4. Zoledronic Acid

2.5. RANKL Inhibitors

Denosumab

3. Comparative Trials

4. Supportive Care and Management of Adverse Events

4.1. Exercise, Weight Loss, and Lifestyle Modifications

4.2. Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation and Hypocalcemia

4.3. Jaw Osteonecrosis

4.4. Patients with Baseline Renal Impairment

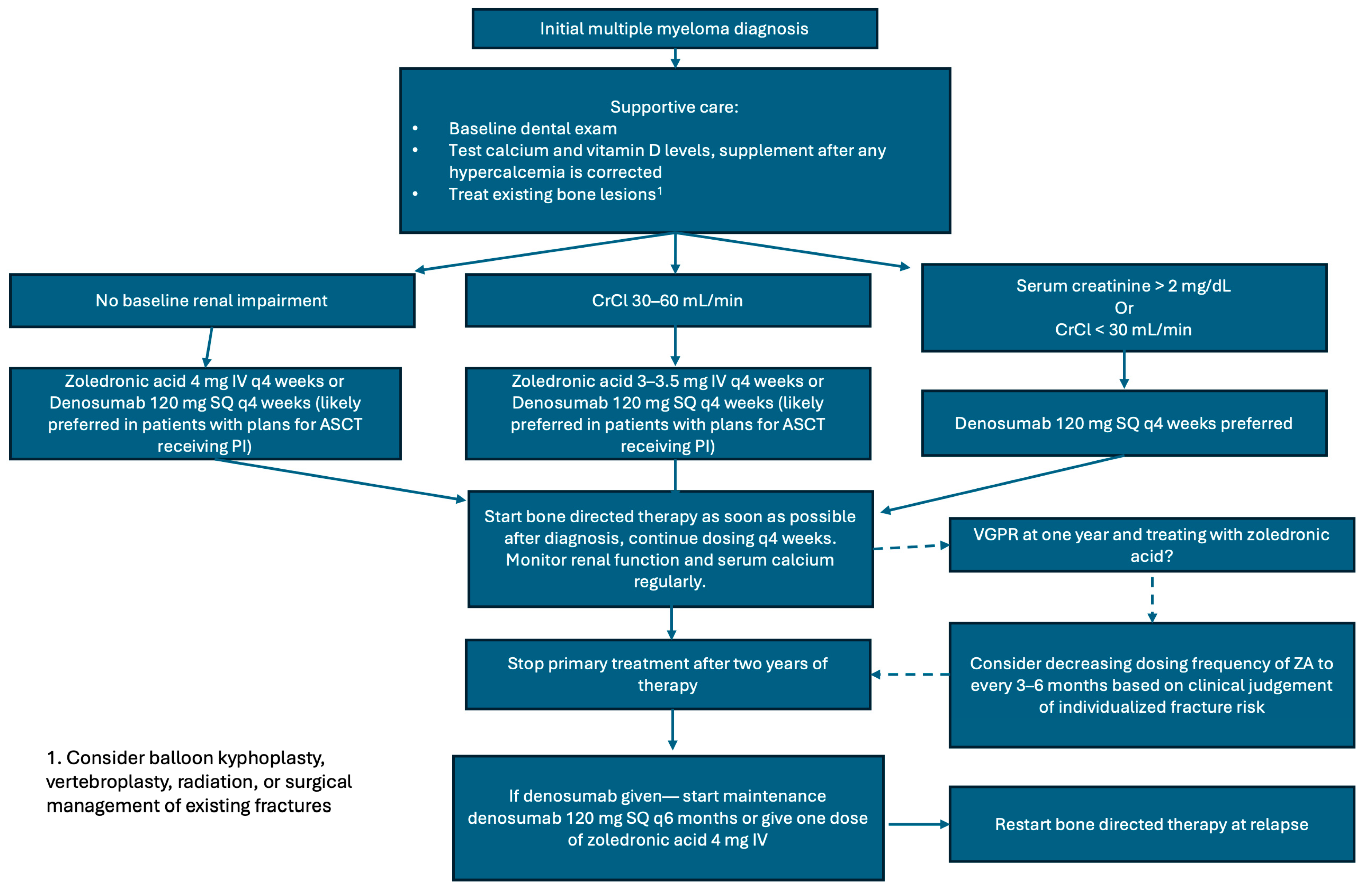

5. Recommendations for the Management of Bone Disease in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma

6. Novel Therapies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANXA2 | annexin A2 |

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| ASCT | autologous stem cell transplantation |

| BMSC | bone marrow stromal cell |

| CCL3 | chemokine ligand 3 |

| CrCl | creatinine clearance |

| DKK-1 | Dickkopf-related protein 1 |

| HSPG | heparan sulfate proteoglycan |

| IMWG | International Myeloma Working Group |

| ISS | international staging system |

| IV | intravenous |

| MM | multiple myeloma |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NDMM | newly diagnosed multiple myeloma |

| ONJ | osteonecrosis of the jaw |

| OPG | osteoprotegerin |

| OS | overall survival |

| PI | Proteosome Inhibitor |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| RVD | lenalidomide (Revlimid), bortezomib (Velcade), dexamethasone |

| S1 | syndecan-1 |

| Sema4D | Semaphorin 4D |

| SDF-1α | stromal cell-derived factor-1α |

| sFRPs | soluble frizzled-related proteins |

| SRE | skeletal-related event |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-beta |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VCD | bortezomib (Velcade), cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone |

| VGPR | very good partial response |

| VLA-4 | very late antigen-4 |

| VTD | bortezomib (Velcade), thalidomide, dexamethasone |

| VD | bortezomib (Velcade), dexamethasone |

References

- Kazandjian, D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: A unique malignancy. Semin. Oncol. 2016, 43, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Myeloma. 2025. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Morgan, G.J.; Child, J.A.; Gregory, W.M.; Szubert, A.J.; Cocks, K.; Bell, S.E.; Navarro-Coy, N.; Drayson, M.T.; Owen, R.G.; Feyler, S.; et al. Effects of zoledronic acid versus clodronic acid on skeletal morbidity in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MRC Myeloma IX): Secondary outcomes from a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R.A.; Gertz, M.A.; Witzig, T.E.; Lust, J.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Dispenzieri, A.; Fonseca, R.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Offord, J.R.; Larson, D.R.; et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2003, 78, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpos, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Myeloma bone disease: From biology findings to treatment approaches. Blood 2019, 133, 1534–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Partridge, N.C. Physiological Bone Remodeling: Systemic Regulation and Growth Factor Involvement. Physiology 2016, 31, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.S.; Bhatta, S.; Terpos, E. Role of the RANK/RANKL Pathway in Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standal, T.; Seidel, C.; Hjertner, Ø.; Plesner, T.; Sanderson, R.D.; Waage, A.; Borset, M.; Sundan, A. Osteoprotegerin is bound, internalized, and degraded by multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2002, 100, 3002–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Calle, J.; Anderson, J.; Cregor, M.D.; Condon, K.W.; Kuhstoss, S.A.; I Plotkin, L.; Bellido, T.; Roodman, G.D. Genetic deletion of Sost or pharmacological inhibition of sclerostin prevent multiple myeloma-induced bone disease without affecting tumor growth. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2686–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.-W.; Chen, Y.; Stephens, O.; Brown, N.; Chen, B.; Epstein, J.; Barlogie, B.; Shaughnessy, J.D. Myeloma-derived Dickkopf-1 disrupts Wnt-regulated osteoprotegerin and RANKL production by osteoblasts: A potential mechanism underlying osteolytic bone lesions in multiple myeloma. Blood 2008, 112, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Christoulas, D.; Bagratuni, T.; Bakogeorgos, M.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou, E.; Kanellias, N.; Kastritis, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Semaphorin 4D correlates with increased bone resorption, hypercalcemia, and disease stage in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Lv, Z.; Zuo, W.; Xiao, Y. From bench to bedside: The promise of sotatercept in hematologic disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckinger, A.; Meiβner, T.; Moreaux, J.; Depeweg, D.; Hillengass, J.; Hose, K.; Rème, T.; Rösen-Wolff, A.; Jauch, A.; Schnettler, R.; et al. Clinical and prognostic role of annexin A2 in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012, 120, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Dallas, M.; Niewolna, M.; Story, B.; Williams, P.J.; Mundy, G.R.; Yoneda, T. Anti-alpha4 integrin antibody suppresses the development of multiple myeloma and associated osteoclastic osteolysis. Blood 2004, 104, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigami, T.; Shimizu, N.; Williams, P.J.; Niewolna, M.; Dallas, S.L.; Mundy, G.R.; Yoneda, T. Cell-cell contact between marrow stromal cells and myeloma cells via VCAM-1 and alpha(4)beta(1)-integrin enhances production of osteoclast-stimulating activity. Blood 2000, 96, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Calle, J.; Anderson, J.; Cregor, M.D.; Hiasa, M.; Chirgwin, J.M.; Carlesso, N.; Yoneda, T.; Mohammad, K.S.; Plotkin, L.I.; Roodman, G.D.; et al. Bidirectional Notch Signaling and Osteocyte-Derived Factors in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment Promote Tumor Cell Proliferation and Bone Destruction in Multiple Myeloma. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, M.T.; Clarke, B.L.; Khosla, S. Bisphosphonates: Mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khan, S.A.; Kanis, J.A.; Vasikaran, S.; Kline, W.F.; Matuszewski, B.K.; McCloskey, E.V.; Beneton, M.N.C.; Gertz, B.J.; Sciberras, D.G.; Holland, S.D.; et al. Elimination and biochemical responses to intravenous alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997, 12, 1700–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso, A.; Ferretti, E.; Lunghi, M.; Zappasodi, P.; Mangiacavalli, S.; De Amici, M.; Rusconi, C.; Varettoni, M.; Lazzarino, M. Zoledronic acid down-regulates adhesion molecules of bone marrow stromal cells in multiple myeloma: A possible mechanism for its antitumor effect. Cancer 2005, 104, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloskey, E.V.; Dunn, J.A.; Kanis, J.A.; MacLennan, I.C.; Drayson, M.T. Long-term follow-up of a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of clodronate in multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2001, 113, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodronate Disodium Product Monograph. Bayer Inc. 2017. Available online: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00038695.PDF (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Lahtinen, R.; Laakso, M.; Palva, I.; Virkkunen, P.; Elomaa, I. Randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial of clodronate in multiple myeloma. Lancet 1992, 340, 1049–1052, Erratum in Lancet 1992, 340, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimsing, P.; Carlson, K.; Turesson, I.; Fayers, P.; Waage, A.; Vangsted, A.; Mylin, A.; Gluud, C.; Juliusson, G.; Gregersen, H.; et al. Effect of pamidronate 30 mg versus 90 mg on physical function in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (Nordic Myeloma Study Group): A double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidronate Highlights of Prescribing Information. FDA Access Data. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/021113s017lbl.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Berenson, J.R.; Lichtenstein, A.; Porter, L.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Bordoni, R.; George, S.; Lipton, A.; Keller, A.; Ballester, O.; Kovacs, M.; et al. Long-term pamidronate treatment of advanced multiple myeloma patients reduces skeletal events. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincker, H.; Westin, J.; Abildgaard, N.; Gimsing, P.; Turesson, I.; Hedenus, M.; Ford, J.; Kandra, A. Failure of oral pamidronate to reduce skeletal morbidity in multiple myeloma: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Danish-Swedish co-operative study group. Br. J. Haematol. 1998, 101, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenson, J.R.; Lichtenstein, A.; Porter, L.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Bordoni, R.; George, S.; Lipton, A.; Keller, A.; Ballester, O.; Kovacs, M.J.; et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.S.; Gordon, D.; Kaminski, M.; Howell, A.; Belch, A.; Mackey, J.; Apffelstaedt, J.; Hussein, M.A.; Coleman, R.E.; Reitsma, D.J.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid compared with pamidronate disodium in the treatment of skeletal complications in patients with advanced multiple myeloma or breast carcinoma: A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, comparative trial. Cancer 2003, 98, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoledronic Acid Highlights of Prescribing Information. FDA Access Data. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/021223s028lbl.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Zoledronic Acid. Hospira Inc. 2019. Available online: https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=7566 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- McClung, M.R.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Cohen, S.B.; Bolognese, M.A.; Woodson, G.C.; Moffett, A.H.; Peacock, M.; Miller, P.D.; Lederman, S.N.; Chesnut, C.H.; et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearse, R.N.; Sordillo, E.M.; Yaccoby, S.; Wong, B.R.; Liau, D.F.; Colman, N.; Michaeli, J.; Epstein, J.; Choi, Y. Multiple myeloma disrupts the TRANCE/osteoprotegerin cytokine axis to trigger bone destruction and promote tumor progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11581–11586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.R.; Ferrari, S.; Eastell, R.; Gilchrist, N.; Jensen, J.-E.B.; McClung, M.; Roux, C.; Törring, O.; Valter, I.; Wang, A.T.; et al. Vertebral Fractures After Discontinuation of Denosumab: A Post Hoc Analysis of the Randomized Placebo-Controlled FREEDOM Trial and Its Extension. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.D.; Bolognese, M.A.; Lewiecki, E.M.; McClung, M.R.; Ding, B.; Austin, M.; Liu, Y.; Martin, J.S. Effect of denosumab on bone density and turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass after long-term continued, discontinued, and restarting of therapy: A randomized blinded phase 2 clinical trial. Bone 2008, 43, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewiecki, E.M. New and emerging concepts in the use of denosumab for the treatment of osteoporosis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2018, 10, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.; Terpos, E.; Willenbacher, W.; Shimizu, K.; García-Sanz, R.; Durie, B.; Legieć, W.; Krejčí, M.; Laribi, K.; Zhu, L.; et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid in bone disease treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: An international, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Raje, N.; Croucher, P.; Garcia-Sanz, R.; Leleu, X.; Pasteiner, W.; Wang, Y.; Glennane, A.; Canon, J.; Pawlyn, C. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid on PFS in multiple myeloma: Exploratory results of an international phase 3 study. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denosumab Highlights of Prescribing Information. FDA Access Data. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/125320s5s6lbl.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Morgan, G.J.; Davies, F.E.; Gregory, W.M.; Cocks, K.; Bell, S.E.; Szubert, A.J.; Navarro-Coy, N.; Drayson, M.T.; Owen, R.G.; Feyler, S.; et al. First-line treatment with zoledronic acid as compared with clodronic acid in multiple myeloma (MRC Myeloma IX): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1989–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raje, N.; Vescio, R.; Montgomery, C.W.; Badros, A.; Munshi, N.; Orlowski, R.; Hadala, J.T.; Warsi, G.; Argonza-Aviles, E.; Ericson, S.G.; et al. Bone Marker-Directed Dosing of Zoledronic Acid for the Prevention of Skeletal Complications in Patients with Multiple Myeloma: Results of the Z-MARK Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himelstein, A.L.; Foster, J.C.; Khatcheressian, J.L.; Roberts, J.D.; Seisler, D.K.; Novotny, P.J.; Qin, R.; Go, R.S.; Grubbs, S.S.; O’cOnnor, T.; et al. Effect of Longer-Interval vs Standard Dosing of Zoledronic Acid on Skeletal Events in Patients With Bone Metastases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, F.P.L.; Cole-Sinclair, M.; Cheng, W.; Quinn, J.M.W.; Gillespie, M.T.; Sentry, J.W.; Schneider, H. Myeloma cells can directly contribute to the pool of RANKL in bone bypassing the classic stromal and osteoblast pathway of osteoclast stimulation. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 126, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, R.; Horvath, N.; Spencer, A.; Taylor, K.; Vadhan-Raj, S.; Vescio, R.; Smith, J.; Qian, Y.; Yeh, H.; Jun, S. An open-label, phase 2 trial of denosumab in the treatment of relapsed or plateau-phase multiple myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2009, 84, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.H.; Costa, L.; Goldwasser, F.; Hirsh, V.; Hungria, V.; Prausova, J.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Sleeboom, H.; Spencer, A.; Vadhan-Raj, S.; et al. Randomized, double-blind study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced cancer (excluding breast and prostate cancer) or multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.; Vadhan-Raj, S.; Willenbacher, W.; Terpos, E.; Hungria, V.; Spencer, A.; Alexeeva, Y.; Facon, T.; Stewart, A.K.; Feng, A.; et al. Evaluating results from the multiple myeloma patient subset treated with denosumab or zoledronic acid in a randomized phase 3 trial. Blood Cancer J. 2016, 6, e378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Heath, D.J.; Rahemtulla, A.; Zervas, K.; Chantry, A.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Pouli, A.; Katodritou, E.; Verrou, E.; Vervessou, E.; et al. Bortezomib reduces serum dickkopf-1 and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand concentrations and normalises indices of bone remodelling in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2006, 135, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heider, U.; Kaiser, M.; Müller, C.; Jakob, C.; Zavrski, I.; Schulz, C.; Fleissner, C.; Hecht, M.; Sezer, O. Bortezomib increases osteoblast activity in myeloma patients irrespective of response to treatment. Eur. J. Haematol. 2006, 77, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrski, I.; Krebbel, H.; Wildemann, B.; Heider, U.; Kaiser, M.; Possinger, K.; Sezer, O. Proteasome inhibitors abrogate osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 333, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Metzler, I.; Krebbel, H.; Hecht, M.; Manz, R.A.; Fleissner, C.; Mieth, M.; Kaiser, M.; Jakob, C.; Sterz, J.; Kleeberg, L.; et al. Bortezomib inhibits human osteoclastogenesis. Leukemia 2007, 21, 2025–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, I.R.; Chen, D.; Gutierrez, G.; Zhao, M.; Escobedo, A.; Rossini, G.; Harris, S.E.; Gallwitz, W.; Kim, K.B.; Hu, S.; et al. Selective inhibitors of the osteoblast proteasome stimulate bone formation in vivo and in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolomsky, A.; Schreder, M.; Meißner, T.; Hose, D.; Ludwig, H.; Pfeifer, S.; Zojer, N. Immunomodulatory drugs thalidomide and lenalidomide affect osteoblast differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells in vitro. Exp. Hematol. 2014, 42, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyuddin, G.R.; Guadamuz, J.S.; Ascha, M.S.; Chiu, B.C.-H.; Patel, P.R.; Sweiss, K.; Rohrer, R.; Sborov, D.; Calip, G.S. Comparison of patients with myeloma receiving zoledronic acid vs denosumab: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 5539–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Body, J.; Terpos, E.; Tombal, B.; Hadji, P.; Arif, A.; Young, A.; Aapro, M.; Coleman, R. Bone health in the elderly cancer patient: A SIOG position paper. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 51, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, H.M.E.; van den Heuvel, E.G.H.M.; Schoemaker, R.J.W.; Klein-Nulend, J.; Bakker, A.D. Diet and Exercise: A Match Made in Bone. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017, 15, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitareewan, W.; Boonhong, J.; Janchai, S.; Aksaranugraha, S. Effects of the treadmill walking exercise on the biochemical bone markers. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2011, 94 (Suppl. S5), S10–S16. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, R.F.; Jarden, M.; Minet, L.R.; Frølund, U.C.; Hermann, A.P.; Breum, L.; Möller, S.; Abildgaard, N. Exercise in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma: A randomized controlled trial of effects on physical function, physical activity, lean body mass, bone mineral density, pain, and quality of life. Eur. J. Haematol. 2024, 113, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What clinicians need to know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Zamagni, E.; Lentzsch, S.; Drake, M.T.; García-Sanz, R.; Abildgaard, N.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Schjesvold, F.; de la Rubia, J.; Kyriakou, C.; et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma-related bone disease: Recommendations from the Bone Working Group of the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e119–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesareo, R.; Attanasio, R.; Caputo, M.; Castello, R.; Chiodini, I.; Falchetti, A.; Guglielmi, R.; Papini, E.; Santonati, A.; Scillitani, A.; et al. Italian Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AME) and Italian Chapter of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) Position Statement: Clinical Management of Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Burr, D.; Cauley, J.; Dempster, D.W.; Ebeling, P.R.; Felsenberg, D.; Gagel, R.F.; Gilsanz, V.; Guise, T.; Koka, S.; et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: Report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007, 22, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: An update. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 13, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Poznak, C.H.; Unger, J.M.; Darke, A.K.; Moinpour, C.; Bagramian, R.A.; Schubert, M.M.; Hansen, L.K.; Floyd, J.D.; Dakhil, S.R.; Lew, D.L.; et al. Association of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw With Zoledronic Acid Treatment for Bone Metastases in Patients With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasilakis, A.D.; Pepe, J.; Napoli, N.; Palermo, A.; Magopoulos, C.; Khan, A.A.; Zillikens, M.C.; Body, J.-J. Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and Antiresorptive Agents in Benign and Malignant Diseases: A Critical Review Organized by the ECTS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 1441–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, F.; Musto, P.; Rota-Scalabrini, D.; Bertamini, L.; Belotti, A.; Galli, M.; Offidani, M.; Zamagni, E.; Ledda, A.; Grasso, M.; et al. Carfilzomib with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone or lenalidomide and dexamethasone plus autologous transplantation or carfilzomib plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone, followed by maintenance with carfilzomib plus lenalidomide or lenalidomide alone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (FORTE): A randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1705–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, P.G.; Jacobus, S.J.; Weller, E.A.; Hassoun, H.; Lonial, S.; Raje, N.S.; Medvedova, E.; McCarthy, P.L.; Libby, E.N.; Voorhees, P.M.; et al. Triplet Therapy, Transplantation, and Maintenance until Progression in Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attal, M.; Lauwers-Cances, V.; Hulin, C.; Leleu, X.; Caillot, D.; Escoffre, M.; Arnulf, B.; Macro, M.; Belhadj, K.; Garderet, L.; et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; Callander, N.S.; Adekola, K.; Anderson, L.; Baljevic, M.; Campagnaro, E.; Castillo, J.J.; Chandler, J.C.; Costello, C.; Efebera, Y.; et al. Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 1685–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.; Ismaila, N.; Flynn, P.J.; Halabi, S.; Jagannath, S.; Ogaily, M.S.; Omel, J.; Raje, N.; Roodman, G.D.; Yee, G.C.; et al. Role of Bone-Modifying Agents in Multiple Myeloma: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avilès, A.; Nambo, M.J.; Huerta-Guzmàn, J.; Cleto, S.; Neri, N. Prolonged Use of Zoledronic Acid (4 Years) Did Not Improve Outcome in Multiple Myeloma Patients. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017, 17, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.; Roodman, G.D.; Willenbacher, W.; Shimizu, K.; García-Sanz, R.; Terpos, E.; Kennedy, L.; Sabatelli, L.; Intorcia, M.; Hechmati, G. A cost-effectiveness analysis of denosumab for the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with multiple myeloma in the United States of America. J. Med. Econ. 2018, 21, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpos, E.; Jamotte, A.; Christodoulopoulou, A.; Campioni, M.; Bhowmik, D.; Kennedy, L.; Willenbacher, W. A cost-effectiveness analysis of denosumab for the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with multiple myeloma in four European countries: Austria, Belgium, Greece, and Italy. J. Med. Econ. 2019, 22, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sanz, R.; Oriol, A.; Moreno, M.J.; de la Rubia, J.; Payer, A.R.; Hernández, M.T.; Palomera, L.; Teruel, A.I.; Blanchard, M.J.; Gironella, M.; et al. Zoledronic acid as compared with observation in multiple myeloma patients at biochemical relapse: Results of the randomized AZABACHE Spanish trial. Haematologica 2015, 100, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romosozumab Highlights of Prescribing Information. FDA Access Data. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761062s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, J.; Niu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shu, G.; Yin, G. Wnt/β-catenin signalling: Function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadis, E.S.; Evangelopoulos, D.-S.; Kaspiris, A.; Benetos, I.S.; Vlachos, C.; Pneumaticos, S.G. The Role of Sclerostin in Bone Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadis, E.S.; Evangelopoulos, D.-S.; Kaspiris, A.; Benetos, I.S.; Vlachos, C.; Pneumaticos, S.G. Bone marrow plasma macrophage inflammatory protein protein-1 alpha(MIP-1 alpha) and sclerostin in multiple myeloma: Relationship with bone disease and clinical characteristics. Leuk. Res. 2014, 38, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.M.; Reagan, M.R.; Youlten, S.E.; Mohanty, S.T.; Seckinger, A.; Terry, R.L.; Pettitt, J.A.; Simic, M.K.; Cheng, T.L.; Morse, A.; et al. Inhibiting the osteocyte-specific protein sclerostin increases bone mass and fracture resistance in multiple myeloma. Blood 2017, 129, 3452–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saag, K.G.; Petersen, J.; Brandi, M.L.; Karaplis, A.C.; Lorentzon, M.; Thomas, T.; Maddox, J.; Fan, M.; Meisner, P.D.; Grauer, A. Romosozumab or Alendronate for Fracture Prevention in Women with Osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewiecki, E.M.; Blicharski, T.; Goemaere, S.; Lippuner, K.; Meisner, P.D.; Miller, P.D.; Miyauchi, A.; Maddox, J.; Chen, L.; Horlait, S. A Phase III Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Men with Osteoporosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3183–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerov, V.; Gerova, D.; Micheva, I.; Nikolova, M.; Mihaylova, G.; Galunska, B. Dynamics of Bone Disease Biomarkers Dickkopf-1 and Sclerostin in Patients with Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Chu, H.Y.; Yu, S.; Yao, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, B.-T. Drug Discovery of DKK1 Inhibitors. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 847387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulciniti, M.; Tassone, P.; Hideshima, T.; Vallet, S.; Nanjappa, P.; Ettenberg, S.A.; Shen, Z.; Patel, N.; Tai, Y.-T.; Chauhan, D.; et al. Anti-DKK1 mAb (BHQ880) as a potential therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma. Blood 2009, 114, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, S.; Beck, J.T.; Kelly, K.R.; Munshi, N.C.; Dzik-Jurasz, A.; Gangolli, E.; Ettenberg, S.; Miner, K.; Bilic, S.; Whyte, W.; et al. A Phase I/II Study of BHQ880, a Novel Osteoblat Activating, Anti-DKK1 Human Monoclonal Antibody, in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma (MM) Patients Treated with Zoledronic Acid (Zol) and Anti-Myeloma Therapy (MM Tx). Blood 2009, 114, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.P.; Beck, J.T.; Stewart, A.K.; Shah, J.; Kelly, K.R.; Isaacs, R.; Bilic, S.; Sen, S.; Munshi, N.C. A Phase IB multicentre dose-determination study of BHQ880 in combination with anti-myeloma therapy and zoledronic acid in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and prior skeletal-related events. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 167, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, N.C.; Abonour, R.; Beck, J.T.; Bensinger, W.; Facon, T.; Stockerl-Goldstein, K.; Baz, R.; Siegel, D.S.; Neben, K.; Lonial, S.; et al. Early Evidence of Anabolic Bone Activity of BHQ880, a Fully Human Anti-DKK1 Neutralizing Antibody: Results of a Phase 2 Study in Previously Untreated Patients with Smoldering Multiple Myeloma At Risk for Progression. Blood 2012, 120, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.L.; Xian, L.; Cao, X. Role of TGF-β Signaling in Coupling Bone Remodeling. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1344, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallet, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Vaghela, N.; Hideshima, T.; Fulciniti, M.; Pozzi, S.; Santo, L.; Cirstea, D.; Patel, K.; Sohani, A.R.; et al. Activin A promotes multiple myeloma-induced osteolysis and is a promising target for myeloma bone disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5124–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotatercept Highlights of Prescribing Information. FDA Access Data. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/761363s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Abdulkadyrov, K.M.; Salogub, G.N.; Khuazheva, N.K.; Sherman, M.L.; Laadem, A.; Barger, R.; Knight, R.; Srinivasan, S.; Terpos, E. Sotatercept in patients with osteolytic lesions of multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 165, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial | Drug | Median Time to First Skeletal-Related Event | Median PFS | Median Overall Survival | Grade ≥ 3 Adverse Events Related to Study Drug | Adverse Events Associated With Renal Toxicity | Hypocalcemia Incidence | Jaw Osteonecrosis Incidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry 1 [44]. | Denosumab | 20.6 months 2 | Not reported, approximately 9 months 3 | Not reported, approximately 12 months 4 | Not reported, total AEs leading to treatment discontinuation 10% (p = 0.20) | 8.3% | 10.8% | 1.1% |

| Zoledronic Acid | 16.3 months 2 | Not reported, approximately 9 months 3 | Not reported, approximately 12 months 4 | Not reported, total AEs leading to treatment discontinuation 12% (p = 0.20) | 10.9% | 5.8% | 1.3% | |

| Raje/Terpos 5 [36,37]. | Denosumab | 22.8 months 6 | 46.1 months 7,8 | 49.5 months 9 | 5% | 10% | 17% | 4% |

| Zoledronic Acid | 24 months 6 | 35.7 months 7,8 | 49.5 months 9 | 6% | 17% | 12% | 3% |

| Preferred Agent | Frequency of Treatment and Dosing | Duration of Treatment | Modify Duration Based on Response | Supportive Care | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMWG: Terpos et al.; Lancet Oncology 2021 [58] | Zoledronic acid (ZA) preferred If patient has no evidence of bone disease, ZA preferred If patient has renal impairment, denosumab preferred | 4 mg monthly intravenously for ZA 120 mg monthly for denosumab | At least 12 months If denosumab is discontinued, a single dose of ZA should be given at least six months after discontinuation of denosumab, or denosumab should continue to be administered every six months | If patients achieve ≥ VGPR, can decrease ZA dosing frequency to every 3 months, 6 months, yearly, or discontinue treatment Denosumab treatment should be continued until unacceptable toxicity occurs, but can be discontinued after 24 months, and if the patient achieves ≥ VGPR | Dental evaluation for all patients at baseline and annually, or if symptoms appear Calcium and vitamin D supplementation Cement augmentation can help treat painful vertebral compression fractures. Radiation can help uncontrolled pain, symptoms related to cord compression, and pathologic fractures. Surgery is indicated for prevention or treatment of long bone pathologic fractures, vertebral column instability, or spinal cord compression | Denosumab may prolong progression-free survival in NDMM with related bone disease in patients who are eligible for autologous transplant, but discontinuation is challenging due to the rebound effect. |

| NCCN: Kumar et al.; JNCCN 2020 [67] | Bisphosphonate [category 1] or denosumab preferred. Denosumab is preferred in patients with renal insufficiency | Frequency of dosing (monthly vs. every three months) depends on the patient, response to therapy, and agent used | Up to two years | Continuing beyond two years is based on clinical judgment | A baseline dental exam is recommended Assess vitamin D status Monitor for renal dysfunction with use of bisphosphonates Monitor for osteonecrosis of the jaw | Patients who discontinue denosumab should be given maintenance denosumab every six months or a single dose of bisphosphonate |

| ASCO Guidelines [68] | Pamidronate or zoledronic acid preferred with denosumab as a non-inferior alternative preferred in patients with renal insufficiency | 90 mg IV pamidronate or 4 mg IV zoledronic acid every 3–4 weeks. Consider reducing the pamidronate dose in cases of renal impairment. | Up to two years | Less frequent dosing should be considered for patient with responsive or stable disease. Continuous use is at the discretion of the treating physician. | Comprehensive dental exam before starting bone-modifying therapy is recommended Calcium and vitamin D should be repleted Monitor for renal dysfunction during treatment Evaluate for albuminuria every 3–6 months for patients on bisphosphonates. Consider discontinuing the drug in patients who develop unexplained urine albumin of >500 mg/24 h. | Retreatment should be initiated at the time of disease relapse |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Massat, B.; Stiff, P.; Esmail, F.; Gauto-Mariotti, E.; Hagen, P. Preventing Skeletal-Related Events in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2025, 14, 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14161263

Massat B, Stiff P, Esmail F, Gauto-Mariotti E, Hagen P. Preventing Skeletal-Related Events in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Cells. 2025; 14(16):1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14161263

Chicago/Turabian StyleMassat, Benjamin, Patrick Stiff, Fatema Esmail, Estefania Gauto-Mariotti, and Patrick Hagen. 2025. "Preventing Skeletal-Related Events in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma" Cells 14, no. 16: 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14161263

APA StyleMassat, B., Stiff, P., Esmail, F., Gauto-Mariotti, E., & Hagen, P. (2025). Preventing Skeletal-Related Events in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Cells, 14(16), 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14161263