Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia globally; however, the aetiology of AD remains elusive hindering the development of effective therapeutics. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are regulators of gene expression and have been of growing interest in recent studies in many pathologies including AD not only for their use as biomarkers but also for their implications in the therapeutic field. In this study, miRNA and protein profiles were obtained from brain tissues of different stage (Braak III-IV and Braak V-VI) of AD patients and compared to matched controls. The aim of the study was to identify in the late stage of AD, the key dysregulated pathways that may contribute to pathogenesis and then to evaluate whether any of these pathways could be detected in the early phase of AD, opening new opportunity for early treatment that could stop or delay the pathology. Six common pathways were found regulated by miRNAs and proteins in the late stage of AD, with one of them (Rap1 signalling) activated since the early phase. MiRNAs and proteins were also compared to explore an inverse trend of expression which could lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets. These results suggest that specific miRNA changes could represent molecular fingerprint of neurodegenerative processes and potential therapeutic targets for early intervention.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of neurodegenerative dementia, leading to severe disability and early death, and with devastating consequences for families, health-care systems, and society [1]. It affects approximately between 40 and 50 million globally, but the number of cases is expected to triple by 2050 owing to population growth and ageing [2,3]. Most AD cases are considered sporadic, and the cause is unclear; however, a notable risk factor is carrying the APOE4 allele of the Apolipoprotein E gene [4]. Fewer than 1% of AD cases are known to be familial, caused by inheritance of rare autosomal dominant mutations [5] of amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, presenilin 1 (PSEN1), and presenilin 2 (PSEN2), where PSEN1 and PSEN2 are involved in the processing of APP to amyloid-beta (Aβ) [6].

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is based on a history of cognitive decline combined with neurological and laboratory analysis, including the measurement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of Aβ and tau tangles and neuroimaging scans to identify brain atrophy and anatomical changes [7]. The histological hallmarks of AD pathology are Aβ-plaques and tau tangles accompanied by neuron loss in the brain. The pathology follows a specific pattern of brain regions in which plaques and tangles are found and mapped according to Braak staging [8].

Although the FDA recently approved the first Alzheimer’s medication clearing out amyloid plaques, this intervention is still controversial, and to date, no treatment has shown a clear/undoubted patient clinical benefit. This may be a consequence of the late-stage diagnosis of patients as well as the fact that the numerous studied compounds are unable to modify the disease process [9]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to discover early mechanistic biomarkers/endpoints as well as new therapeutic targets.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs, miRs), a small non-coding RNA class of post-transcriptional regulators, are particularly attractive molecules due to their ability to regulate multiple genes. Technology has now been developed to isolate, quantify, and profile miRNAs in diseases and is being combined with approaches to deliver miRNA therapeutics effectively without an immunogenic response [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Whilst these developments are promising, there are currently no miRNA therapeutics available; however, there is a remarkable effort in place, with many entering clinical trials with the earliest implication for cancer [18]. Consequently, miRNA as a therapy presents a promising solution for multifactorial diseases, such as AD, which do not yet have successful disease-modifying treatments; however, further research is required to elucidate the potential role of miRNA in this complex pathology. Previous studies in AD patients have highlighted changes in the expression of miRNAs that target AD-related mRNA and proteins. Among them, miR-101 and miR-16 have been shown to target APP mRNA [19,20]. MiR-124 was downregulated in the AD model SAMP8 mice, leading to enhanced expression of the splicing regulator PTBP1 and aberrant APP splicing [21]. Several miRNAs are involved in the amyloid cascade through the regulation of beta-secretase 1 (BACE1), including miR-107, miR-29a/b-1, miR-29c, miR-188-3p, miR-339-5p, miR-195, miR-186, and miR-124 in animal and human studies [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Other miRNAs that target the catalytic subunits of γ-secretase have also been shown to be deregulated in AD. Furthermore, Tau protein, the main constituent of neurofibrillary tangles, has been shown to be regulated by miR-132 and miR-34a [29].

In this study, we present an integrated analysis of miRNA and protein expression from the brains of AD patients. The primary outcome was to elucidate the pathological mechanism that can lead to neuronal death in confirmed and late AD cases. This was reached through the expression analyses of miRNAs and proteins and their related pathways in controls and AD (Braak V-VI stage) patients. The secondary outcome had the aim to investigate whether any of these pathological mechanisms or pathways detected in the late stage of AD were also present at the early stage of AD (Braak III-IV) and consequently whether any of the molecules differentially expressed can be used as early indicators of the pathology or as potential targets to stop or delay the progress of the pathology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Population

Post-mortem temporal cortex brain tissues were used in this study, which had been taken within 72 h of death and obtained from the South-West Dementia Brain Bank (SWDBB, Bristol, UK) and stored at −80 °C. Samples were stratified by Braak tangle stages I-VI. Stages I and II were used as the control group (n = 5), stages III-IV were used for the early stage of AD group (n = 5), and stages V and VI were used for the late-stage of AD group (n = 5). The groups were sex- and age-matched to remove these variables as a potential confounding factor.

2.2. MicroRNA Analysis

2.2.1. RNA Extraction and Analysis

Temporal cortex samples were homogenised for 30 s using a TissueRuptor II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in RNase-free PBS (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA was extracted from the homogenised samples using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentration was measured on a nanophotometer (IMPLEN, Westlake Village, CA, USA).

An Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to detect the size distribution of total RNA as well as determine the quality of the RNA. A total of 100 ng of RNA was extracted and converted to cDNA using the miRCURY LNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was mixed with a SYBR master-mix (miRCURY SYBR Green Master Mix; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). This was added to the miRCURY LNA miRNA miRNome Panel I–II using the automated pipettor the QIAgility (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). These plates were run on the Quantstudio 5 qPCR machine (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as instructed by protocol provided with the panels. In total 751miRNAs (miRCURY LNA miRNA miRNome PCR Panels, https://geneglobe.qiagen.com/us/product-groups/mircury-lna-mirna-mirnome-pcr-panels, accessed on 6 October 2019 were tested using the miRNome plates for each of the samples. Overall, 705 miRNAs showed Cq values, and fold changes were calculated using the ΔΔCq method. hsa-miR-99a-5p and hsa-miR-361-5p were selected as the most stable pair of miRNAs across the samples (stability value = 0.05) by NormFinder software (https://moma.dk/normfinder-software, accessed on 1 December 2019 and therefore used as the housekeeping genes.

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

Fold change values were tested for normality and found to not be normally distributed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Mann–Whitney U tests was used to test differences in miRNA expression between two groups. To check for variability across different groups, a heat map analysis was performed.

2.2.3. MiRNA Targets and Pathways Analysis

Diana tools mirPath v.3 (http://snf-515788.vm.okeanos.grnet.gr/, accessed on 20 June 2021) was used for the downstream analysis. The DIANA-microT-CDS algorithm with a set threshold of 0.8 was used to select mRNA targets on the gene union tool. The final p-value was corrected with FDR. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, Kyoto, Japan) pathways analysis was also performed.

2.3. Protein Analysis

2.3.1. Protein Extraction and Analysis

Proteins were extracted with scioExtract buffer (Sciomics, Neckargemünd, Germany) using the extraction SOPs. The bulk protein concentration was determined by BCA assay. The reference samples and the samples were labelled for two hours with scioDye 1 and scioDye 2, respectively. After that the reaction was stopped, the buffer exchanged to PBS and samples stored at −20 °C until use.

Samples were analysed in a dual-colour approach using a reference-based design on scioDiscover antibody microarrays (Sciomics, Neckargemünd, Germany) targeting 1351 different proteins with 1821 antibodies in four replicates. The arrays were blocked with scioBlock (Sciomics, Neckargemünd, Germany) on a Hybstation 4800 (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland), and afterwards the samples were incubated competitively with the reference sample using a dual-colour approach. After incubation for three hours, the slides were thoroughly washed with 1× PBSTT, rinsed with 0.1× PBS and water, and finally dried with nitrogen.

2.3.2. Data Acquisition and Statistical Analysis

Slide scanning was conducted using a Powerscanner (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) with constant instrument power and PMT settings. Spot segmentation was performed with GenePix Pro 6.0 (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA). Data were analysed using the linear models for microarray data (LIMMA) package of R-Bioconductor. For the normalisation, a specialised invariant Lowess method was applied. For analysis of the samples, a one-factorial linear model was fitted with LIMMA resulting in a two-sided t-test or F-test based on moderated statistics. All presented p-values were adjusted for multiple testing by controlling the false discovery rate according to Benjamini and Hochberg. Proteins were defined as deferential for ׀logFCj׀ > 0.5 and an adjusted p-value < 0.05. Proteins differentially expressed between groups are presented as log-fold changes (logFC) calculated for the basis 2. When samples versus controls are compared, a logFC = 1 means that the sample group had on average a 21 = 2-fold higher signal than the control group. logFC = −1 stands for 2−1 = 1/2 of the signal in the sample as compared to the control group.

2.3.3. Pathway Analysis

Proteins were defined as significantly differential for |log2FC| ≥ 0.5 and a simultaneous adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05. All differential proteins were subjected to STRING (search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes/proteins) analysis for the visualization of protein networks, pathway analysis (based on KEGG and Reactome databases), as well as biological function classification analysis (based on the gene ontology (GO) database). KEGG pathways only are shown in this paper.

2.4. Pathway Studio

As part of our pathway analysis and gene ontology representation, we utilized the Elsevier’s PathwayStudio v. 10 (https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/pathway-studio-biological-research, accessed on 20 June 2021). This software handles high throughput “omics” data that can be interrogated for functional analysis and interactome assessment. For this purpose, differential proteins and altered miRNAs were evaluated using the propriety PathwayStudio ResNet database gene analysis. “Subnetwork Enrichment Analysis” (SNEA) algorithm builds functional pathways where Fisher’s statistical test is used to associate one differential hit (gene/protein/microRNA, etc.) to a specific molecular function, pathway, or biological process with the option of localizing these in cellular compartments. The association is categorized into protein modification targets, regulation targets binding partners, and expression targets.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. For each group, 3F and 2M samples were selected. The average age ± standard deviation for the control group was 85.4 ± 9.2; 82 ± 4.5 and 84.4 ± 6.8 for Braak III-IV and Braak V-VI respectively. The average post-mortem delay ± standard deviation for control group was 49.7 ± 13.00; 35.8 ± 20.18 and 43.25 ± 17.68 for Braak III-IV and Braak V-VI respectively. History of diagnosis, Braak tangle stage, and CERAD (Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease) are also reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of samples received from South-West Dementia Brain Bank. CAA= cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

3.2. MicroRNA Analysis

Fifty-four differentially expressed miRNAs (DE-miRNAs) were found, of which 14 were substantially different between control and Braak stage III-IV and 44 between control and Braak stage V-VI (Table 2). A further analysis comparing Braak stage III-IV versus Braak stage V-VI is available in (Supplementary Materials Table S1).

Table 2.

DE-miRNA in Braak stage III-IV and Braak stage V-VI compared to controls (Braak stage I-II). Fold changes (FD), standard deviation (SD), and p-values ≤ 0.05 are reported.

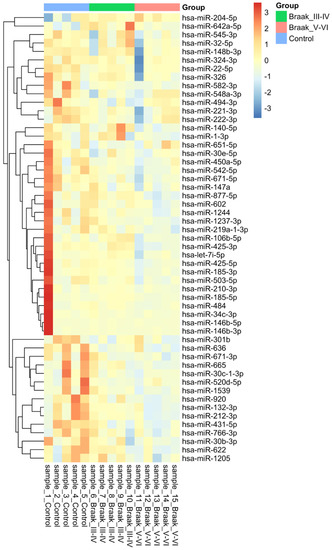

These changes can also be visualised using a hierarchal clustered heatmap (Figure 1). There is a clear shift towards blue in the Braak stage V-VI, whereas the control group is red, with the Braak stage III-IV sharing differences with both sides airing closer to the control group. Overall, this visual representation demonstrates that the majority of differentially expressed miRNAs are downregulated as the disease progresses.

Figure 1.

Heatmap showing the expression of 54 differentially regulated microRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Fifty-four microRNAs were found using Mann–Whitney statistical analysis across the 2 different comparisons, Control vs. Braak stage III-IV and Control vs. Braak stage V-VI. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Hierarchal clustering is present on the left with colours relevant to their group. This was made using heatmap.2 in the R programming language with complete linkage, and Euclidean distance used to compute.

3.3. Protein Analysis

Upon extraction, one sample (Braak stage III-IV) featured a slightly red colour indicating either a higher blood content or some impurities in the extraction process. In addition, this sample was tagged in the quality control analysis due to lower overall signal intensities. Therefore, this sample was excluded from the biostatistical analysis.

Fold changes and statistically significant proteins are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

DE-proteins in Braak stage III-IV and Braak stage V-VI compared to controls (Braak stage I-II). Fold changes (LogFC), standard deviation, and adj. p-values ≤ 0.05 are reported.

Comparing the AD subtypes with controls, 73 differential proteins were identified for Braak stage III-IV and 119 for Braak stage V-VI. In addition, 18 proteins were differential for both AD subtypes.

A further comparison (Braak stage III-IV vs. Braak stage V-VI) is available in (Supplementary Materials Table S2).

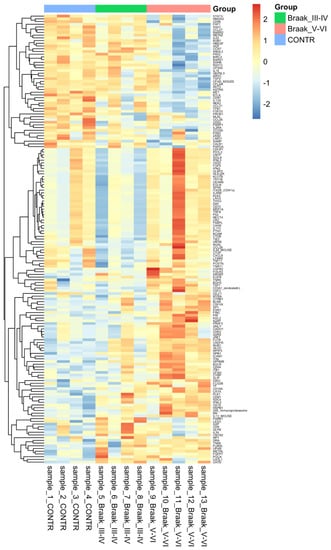

Relative expression levels for differential proteins identified across all comparisons with both ׀logFC׀ > 0.5 and adj. p-value < 0.001 are summarised in heat map Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Heatmap showing the expression of 174 differentially regulated proteins in Alzheimer’s disease across the 2 compariosns Control vs. Braak stage IiI–IV and Control vs. Braak stage V-VI. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Hierarchal clustering is present on the left with colours relevant to their group. This was made using heatmap.2 in the R programming language with complete linkage, and Euclidean distance used to compute.

3.4. MiRNA Target and Pathways Analysis

MiRNA targets of DE-miRNA were selected using DIANA tools as described above. The predicted target genes for DE-miRNAs were compared against differentially expressed proteins (DE-proteins) found in the brain samples. Inverse relationships between expression of miRNA and target proteins were checked and showed one case in Braak stage III-IV and 34 cases in Braak stage V-VI (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of predicted targets for DE-miRNA in Braak III-IV and Braak V-VI and matched DE-proteins with an inverse relation.

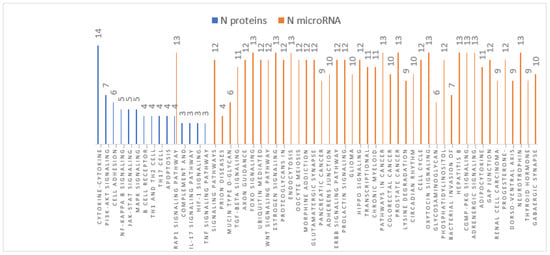

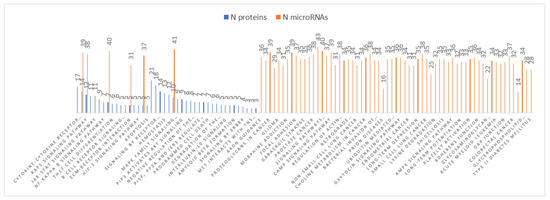

Pathways analyses obtained for both DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins were compared and resulted in one common pathway (Rap1 signalling pathway) in Braak stage III-IV (Figure 3) and six pathways (ECM-receptor interaction, MAPK signalling pathway, Ras signalling pathway, PI3K-Akt signalling pathway, FoxO signalling pathway, and Rap1 signalling pathway) in Braak stage V-VI (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Braak stage III-IV pathways analyses.

Figure 4.

Braak stage V-VI pathways analyses.

Pathways analyses obtained for both DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins in Braak stage III-IV.showed one common pathway (Rap1 signalling pathway).

Pathways analyses obtained for both DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins in Braak stage V-VI. showed six common pathways (ECM-receptor interaction, MAPK signalling pathway, Ras signalling pathway, PI3K-Akt signalling pathway, FoxO signalling pathway, and Rap1 signalling pathway).

In Rap1 signalling pathway of Braak stage III-IV, no inverse relation was found between miRNA targets and proteins analysed in this study. In the six common pathways identified in Braak stage V-VI, the inverse relations between DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Common pathways identified in DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins in Braak stage V-VI. For each of the pathways, the involved microRNAs and the correspondent predicted targets are listed. The protein targets identified in this study with an inverse relation are in bold.

Some of these inverse relationships were verified by using ELISA kits (all details are presented in Supplementary Materials).

3.5. Pathway Studio

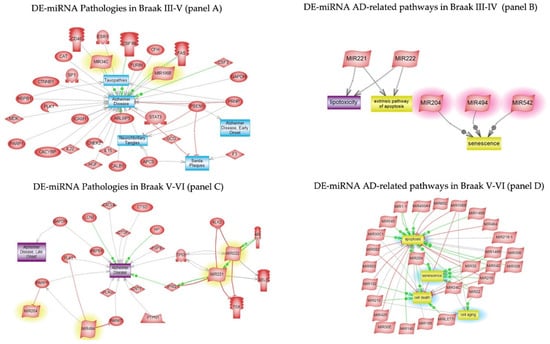

Pathway studio was interrogated to analyse DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins at early and late stage of AD. Figure 5 panel A shows the pathological processes triggered by Braak III-IV DE-miRNA. The most relevant AD pathways, namely lipotoxicity, apoptosis, and senescence, are shown in panel B of the same figure. The senescence pathway showed to be regulated by miR-204, one of the most significantly expressed miRs of early AD. In panel C and D, the pathological processes of miRNA targets and the main AD Braak V-VI pathway-related ones, including cell death, cell ageing, senescence, and apoptosis are shown, respectively.

Figure 5.

DE-miRNA pathway studio analyses in Braak III-IV and Braak V-VI. The pathological processes triggered by Braak III-IV DE-miRNA (panel A) and Braak V-VI DE-miRNA (panel C). The related pathways of Braak III-IV DE-miRNA (panel B) and Braak V-VI DE-miRNA (panel D).

DE-proteins pathways are represented in Figure 6 and confirmed the ECM and cell-cell adhesion among the main processes regulated during AD development.

Figure 6.

DE-protein pathway studio analyses in Braak III-IV and Braak V-VI. AD pathways generated by DE-proteins in Braak III-IV (panel A) and Braak V-VI DE-miRNA (panel B).

4. Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease is a complex, multifactorial disease with no available treatment due to the lack of understanding of causative factors of the disease. It is also difficult to diagnose AD early in the disease process because of the late onset nature of symptoms and the lack of clinical clarity between AD and other neurodegenerative and neurocognitive diseases. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the initiation of neurodegeneration is critical, and the early stages of disease may present a valuable therapeutic window before irreversible brain damage has occurred. Therefore, in this paper, we had two main objectives; the first one was to identify the molecular mechanisms and the cellular processes developed in the late and confirmed cases of AD. We achieved this outcome profiling microRNAs and proteins in the brains of AD Braak V-VI patients. The microRNAs and proteins found significantly and differentially expressed were then used for advanced bioinformatic analyses to determine their relative pathways. In addition, an inverse relation between miRs and protein targets was also investigated. The inverse association with protein targets has a greater likelihood of directly targeting those proteins, making them suitable for miRNA therapy.

The second objective was to perform the same analyses as above using brain tissue of AD patients at an early stage (Braak III-IV) and comparing them to controls. This second outcome was to evaluate if any of the mechanisms detected in the late phase of AD could be earlier identified, therefore opening a window for potential early interventions.

MiRNAs were a phenomenon discovered in 1993, and ever since, there has been much interest in their ability to regulate gene expression within diseases [30]. More recently, they have been studied as biomarker candidates of many pathologies, including AD, in blood and CSF [31,32]. A comparison between blood/CSF miRNAs and brain DE-miRNAs of this research is available in (Supplementary Materials Table S3). Results matched 14 DE-miRNAs between biofluids and brain tissue, offering an alternative way of non-invasively monitoring any change or advancement of AD pathology.

In this study, we identified 14 DE-miRNAs and 73 DE-proteins between the control and early stage of AD samples. An inverse expression was seen in the upregulation of miR-204-5p and its potential downregulated target SELE (selection E), a protein responsible for accumulation of leukocytes at the sites of inflammation. MiR-204 was also depicted by our analysis using pathway studio as key regulator of senescence (Figure 5, panel B). Other studies showed miR-204-5p to be one of the most abundantly expressed in AD [33] and upregulated in sporadic Parkinson’s disease patients, leading to apoptosis of dopaminergic cells in the brain [34]. However, none was able to prove that SELE was a miR-204-5p target.

Bioinformatic analysis revealed 58 mutual KEGG pathways between Braak III-IV DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins and one common pathway, the R1 signalling pathway. Rap1 is a small GTPase that controls diverse processes, such as cell adhesion, cell-cell junction formation, and cell polarity, by regulating the function of integrins and other adhesion molecules [35,36]. Previous studies showed that inhibition of Rap1 interactions reduces Ca2+ dysfunction and improves neuronal survival [37].

Cell adhesion and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation are two pathways found regulated by DE-proteins of early AD using pathway studio. The same pathways were also found in DE-miRNAs and DE-proteins of the late stage of AD.

In the late stage of AD, we reported 44 DE-miRNAs compared to control, of which four were in common with the early stage of AD, and 119 DE-proteins, of which 18 were in common with the early stage. By identifying miRNAs and target proteins with an inverse expression, we were also able to select 34 potential connections that may play a role in AD pathology (Table 4). The associated KEGG pathways also helped to understand the possible cellular effects of each deregulated miRNA. Forty-two pathways were found in proteins and 69 in microRNAs and six pathways were in common: ECM-receptor interaction, MAPK signalling pathway, Ras signalling pathway, PI3K-Akt signalling pathway, FoxO signalling pathway, and Rap1 signalling pathway.

The first pathway, the ECM-receptor interaction, also confirmed by the pathway studio analysis of DE-proteins, is related to cellular integrity and consists of proteoglycans/glycosaminoglycans (PGs/GAGs), proteins, proteinases, and cytokines, which surround cells and facilitate intercellular communication [38]. In CNS, fibrous proteins (collagen, elastin) and adhesive glycoproteins (laminin, fibronectin) were responsible for the strength and elasticity of the ECM [39,40]. ECM also regulates intercellular communication and coordinate processes, such as cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis as well as tissue morphogenesis and homeostasis [41,42], and aberrant expression of the ECM components in the brain can lead to neuro-development disorders, psychiatric dysregulation, and neuro-degenerative diseases [43,44]. An upregulation of collagen IV, laminin, and fibronectin in the brains of AD and a co-localization with Senile Plaques was also proven [45].

In our study, we found several inverse expressions between miRs and proteins with a function in the ECM pathway. Among them, we found hsa-miR-671-5p and Thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), an adhesive glycoprotein that mediates cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions. This protein can bind to fibrinogen, fibronectin, laminin, type V collagen, and integrins alpha-V/beta-1, hsa-miR-132-3p, and hsa-miR-212-3p, inversely related to CD44, which was previously found upregulated in severe Alzheimer’s disease [46]. hsa-miR-30e-5p and Integrin beta-1 (ITGB1), a receptor for collagen, is another interaction, and it was suggested to undergo plasticity through interactions with ECM proteins, modulating ion channels, intracellular Ca2+ and protein kinases signalling, and reorganization of cytoskeletal filaments [47]. ECM and integrin aberrations are likely to contribute to imbalanced synaptic function in epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, mental deficiency, schizophrenia, and other brain conditions [48]. hsa-miR-1-3p, hsa-miR-425-3p, and hsa-miR-1237-3p are all downregulated, and all show the upregulated fibronectin (FN1) as potential target. Fibronectin is the adhesive protein that connects cells with collagen fibres in the ECM, binds to cell-surface integrin regulating cytoskeleton reorganization, and facilitates cell migration [48,49,50,51,52,53].

In addition, several studies reported that the upregulation of fibronectin enhanced the adherence of microglial cells and lead to APP secretion [54,55] and Aβ aggregation in AD pathogenesis.

The other five pathways found to be compromised in the late stage of AD are MAPK, FoxO, Rap1, Ras, and PI3K-Akt signalling pathways. These are intracellular signalling pathways and are required for signal relay, signal amplification, and integration of stimuli in the cell, leading to proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation.

The MAPK signalling pathway is key for signal transduction between neurons and is involved in the maintenance of synaptic plasticity, which is reduced with progression of AD [56]. In particular, p38 MAPK is stimulated by phosphorylated tau, normal dephosphorylated tau, and Aβ oligomers, leading to inflammatory signalling and activation of microglia in AD and inhibition of p38 MAPK pathways, successfully reducing Aβ and memory loss in AD mice [56,57,58,59,60] and suggesting this MAPK signalling as an important therapeutic target.

FoxO signalling pathway is active in many parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens. It functions to determine cell fate and survival, leading to apoptosis, cell proliferation, and differentiation. Dysregulation of FoxOs can lead to increased apoptosis and oxidative stress [61,62]. Some studies also suggest that FoxO proteins may be a downstream target of APP, leading to an APP intracellular domain induced death in neurones, with APP as a transcriptional coactivator of FoxO proteins [63]. Other studies speculated that FoxO proteins may also be upstream regulators of APP [64].

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway seems to be particularly important for mediating neuronal survival [65], playing a role in learning and memory as well [66,67]. It is also involved in the pathogenesis of acute cerebrovascular disease, neurodegeneration diseases, epilepsies, and AD [68,69]. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) was one of the inverse expressed targets in this pathway, and several studies demonstrated that EGFR inhibitors improve pathological and behavioural conditions in AD [70,71]. Moreover, EGFR expression is up-regulated in reactive astrocytes, and its hyper-activation leads to astrogliosis [72,73]. The neuroprotective effect of EGFR inhibition was demonstrated in ALS also [71]. EGFR is regulated by miR-1-3p, and this interaction was already found in cancer [74].

Finally, research groups also reported an increased Ras expression in cells with upregulated APP expression, which could lead to deregulation of the cell cycle [75].

Limitations

All samples used in this study were collected within 72 h of death and then frozen. This long interval of time could have affected the miRNA abundance due to the degradation of the miRNAs. The sample size for all groups (n = 5 per group) was small, and the control and AD groups decreased to n = 4 for the protein microarray. Due to the exploratory nature and the small sample size of the study, differences between groups in miRNAs are presented without adjustments for multiple comparisons; thus, further studies with larger numbers of samples will be required to assess the reproducibility of these findings.

Moreover, we were unable to test for specific proteins in the microarray because of the Sciomics customised platform (1351 proteins only) for this analysis. As result, not all specific targets of the differential miRNAs have been analysed, and the blind analysis of proteins limited the comparison to miRNA expression in this study; therefore, it is important to look at specific protein targets in the future.

Finally, of the 2300 known miRNAs in the human brain, only 751 were analysed for differential expression in this study. This will be an important avenue for future investigation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that miRNAs and proteins are differentially expressed in the early and late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The correlation between their expression must be explored further to understand how these miRNAs regulate gene expression in disease progression. In addition, mutual signalling pathways between the differential miRNAs and proteins were investigated, showing only one common pathway (the Rap1 signalling) between the early and late stage of AD.

While the differentially expressed miRNAs and mutual signalling pathways that were found in this study are in line with previous work, new interactions between miRNA and protein targets were also identified. These novel findings must be investigated further to gain a deeper understanding of their roles in AD and their potential use as therapeutic targets. The results of this can be taken as a basis for future, larger-scale studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cells11010163/s1, Table S1: DE-miRNAs of Braak stage III-IV compared to Braak stage V-VI. Table S2: DE-proteins of Braak stage III-IV compared to Braak stage V-VI. Figure S1: FN1 and EFGR protein concentrations after ELISA quantification. Table S3: DE-miRNAs of AD brain tissues identifidied in this study compared to DE-miRNAs of different biofluids identified in literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N.W., S.M., F.K., A.B. and V.D.P.; methodology, C.N.W., G.B. and V.D.P.; validation, K.M.Y., F.K., S.M. and V.D.P.; formal analysis, E.A., D.T., M.A.H., A.N. and F.K.; investigation, C.N.W., G.B. and K.M.Y.; resources, C.N.W. and G.B.; data curation, C.N.W., G.B., K.M.Y. and V.D.P.; writing original draft preparation, C.N.W. and V.D.P.; writing—review and editing, all. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by ARUK small Research Grant and by the University of Birmingham (UK).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the NHS Rec generic approvals of Research Tissue Bank (18/SW/0029) on the 17 May 2019.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the South-West Dementia Brain Bank (SWDBB) for providing brain tissue for this study. The SWDBB is part of the Brains for Dementia Research programme, jointly funded by Alzheimer’s Research UK and Alzheimer’s Society and is supported by BRACE (Bristol Research into Alzheimer’s and Care of the Elderly) and the Medical Research Council.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Nichols, E.; Szoeke, C.E.I.; Vollset, S.E.; Abbasi, N.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Aichour, M.T.E.; Akinyemi, R.O.; Alahdab, F.; Asgedom, S.W.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Worldwide Dementia Cases to Triple by 2050. Available online: https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/worldwide-dementia-cases-to-triple-by-2050 (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Kim, J.; Basak, J.M.; Holtzman, D.M. The Role of Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2009, 63, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bekris, L.M.; Yu, C.-E.; Bird, T.D.; Tsuang, D.W. Review Article: Genetics of Alzheimer Disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2010, 23, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lane, C.A.; Hardy, J.; Schott, J.M. Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2017, 25, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The Diagnosis of Dementia due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Neuropathological Stageing of Alzheimer-Related Changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991, 82, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R. Recently Approved Alzheimer Drug Raises Questions That Might Never Be Answered. JAMA 2021, 326, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gemeinhart, R.A. Progress in MicroRNA Delivery. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ohno, S.; Takanashi, M.; Sudo, K.; Ueda, S.; Ishikawa, A.; Matsuyama, N.; Fujita, K.; Mizutani, T.; Ohgi, T.; Ochiya, T.; et al. Systemically Injected Exosomes Targeted to EGFR Deliver Antitumor MicroRNA to Breast Cancer Cells. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Yu, B.; Ren, W.; Mo, X.; Zhou, C.; He, H.; Jia, H.; Wang, L.; Jacob, S.T.; Lee, R.J.; et al. Enhanced Hepatic Delivery of SiRNA and MicroRNA Using Oleic Acid Based Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. Improved Targeting of MiRNA with Antisense Oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 2294–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Carrillo, E.; Liu, Y.P.; Berkhout, B. Improving MiRNA Delivery by Optimizing MiRNA Expression Cassettes in Diverse Virus Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2017, 28, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, H.J.; Green, J.J.; Tzeng, S.Y. Cancer-Targeting Nanoparticles for Combinatorial Nucleic Acid Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2019, 32, 1901081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torchilin, V.P. Recent Advances with Liposomes as Pharmaceutical Carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.A.; Rice, K.G. Engineered Nanoscaled Polyplex Gene Delivery Systems. Mol. Pharm. 2009, 6, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, G.A.; Dumitru, C.D.; Shimizu, M.; Bichi, R.; Zupo, S.; Noch, E.; Aldler, H.; Rattan, S.; Keating, M.; Rai, K.; et al. Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations and Applications: Frequent Deletions and Down-Regulation of Micro- RNA Genes MiR15 and MiR16 at 13q14 in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15524–15529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Zhu, J.; Shu, P.; Yin, B.; Gong, Y.; Qiang, B.; Yuan, J.; Peng, X. MicroRNA-16 Targets Amyloid Precursor Protein to Potentially Modulate Alzheimer’s-Associated Pathogenesis in SAMP8 Mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012, 33, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, C.; Pezzola, S.; Caggiano, C.; Antonelli, M.; Frisone, P.; Ciotti, M.T.; Ruberti, F. A Lentiviral Sponge for MiR-101 Regulates RanBP9 Expression and Amyloid Precursor Protein Metabolism in Hippocampal Neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makeyev, E.V.; Zhang, J.; Carrasco, M.A.; Maniatis, T. The MicroRNA MiR-124 Promotes Neuronal Differentiation by Triggering Brain-Specific Alternative Pre-MRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hebert, S.S.; Horre, K.; Nicolai, L.; Papadopoulou, A.S.; Mandemakers, W.; Silahtaroglu, A.N.; Kauppinen, S.; Delacourte, A.; De Strooper, B. Loss of MicroRNA Cluster MiR-29a/B-1 in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease Correlates with Increased BACE1/ -Secretase Expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6415–6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, G.; Song, Y.; Zhou, X.; Deng, Y.; Liu, T.; Weng, G.; Yu, D.; Pan, S. MicroRNA-29c Targets β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein-Cleaving Enzyme 1 and Has a Neuroprotective Role in Vitro and in Vivo. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 3081–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, M.; Teng, Z.; Tang, Y.-P.; Chen, C. Synaptic and Cognitive Improvements by Inhibition of 2-AG Metabolism Are through Upregulation of MicroRNA-188-3p in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 14919–14933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Long, J.M.; Ray, B.; Lahiri, D.K. MicroRNA-339-5p Down-Regulates Protein Expression of β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein-Cleaving Enzyme 1 (BACE1) in Human Primary Brain Cultures and Is Reduced in Brain Tissue Specimens of Alzheimer Disease Subjects. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 289, 5184–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ai, J.; Sun, L.-H.; Che, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, T.-Z.; Wu, W.-C.; Su, X.-L.; Chen, X.; Yang, G.; Li, K.; et al. MicroRNA-195 Protects against Dementia Induced by Chronic Brain Hypoperfusion via Its Anti-Amyloidogenic Effect in Rats. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 3989–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yoon, H.; Chung, D.; Brown, J.L.; Belmonte, K.C.; Kim, J. MiR-186 Is Decreased in Aged Brain and Suppresses BACE1 Expression. J. Neurochem. 2016, 137, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fang, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Geng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Rudd, J.A.; Ling, S.; Chen, W.; Han, S. The MiR-124 Regulates the Expression of BACE1/β-Secretase Correlated with Cell Death in Alzheimer’s Disease. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 209, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.Y.; Hernandez-Rapp, J.; Jolivette, F.; Lecours, C.; Bisht, K.; Goupil, C.; Dorval, V.; Parsi, S.; Morin, F.; Planel, E.; et al. MiR-132/212 Deficiency Impairs Tau Metabolism and Promotes Pathological Aggregationin Vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 6721–6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhaskaran, M.; Mohan, M. MicroRNAs. Vet. Pathol. 2013, 51, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, W.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ma, L.N.; Zhang, T.T.; Cao, Y.; Li, H. MicroRNAs in Alzheimer’s Disease: Function and potential application as diagnostics biomarkers. Font. Mol. Neuorsci. 2020, 13, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, S.C.; Liang, X.; Zhu, H.; Jia, Y.; Leung, S.W. Prediction of differentially expressed microRNAs in blood as potential biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease by meta-analysis and adaptive boosting ensemble learning. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.X.; Fardo, D.W.; Jicha, G.A.; Nelson, P.T. A Customized Quantitative PCR MicroRNA Panel Provides a Technically Robust Context for Studying Neurodegenerative Disease Biomarkers and Indicates a High Correlation between Cerebrospinal Fluid and Choroid Plexus MicroRNA Expression. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 54, 8191–8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.-C.; Yeh, T.-H.; Chen, R.-S.; Chen, H.-C.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Weng, Y.-H.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Liu, Y.-C.; Cheng, A.-J.; Lu, Y.-C.; et al. Upregulated Expression of MicroRNA-204-5p Leads to the Death of Dopaminergic Cells by Targeting DYRK1A-Mediated Apoptotic Signaling Cascade. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bos, J.L. Linking Rap to Cell Adhesion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005, 17, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Ye, F.; Ginsberg, M.H. Regulation of Integrin Activation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 27, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumbacher, M.; Van Dooren, T.; Princen, K.; De Witte, K.; Farinelli, M.; Lievens, S.; Tavernier, J.; Dehaen, W.; Wera, S.; Winderickx, J.; et al. Modifying Rap1-Signalling by Targeting Pde6δ Is Neuroprotective in Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2018, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, C.; Stewart, K.M.; Weaver, V.M. The Extracellular Matrix at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 4195–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hubert, T.; Grimal, S.; Carroll, P.; Fichard-Carroll, A. Collagens in the Developing and Diseased Nervous System. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 66, 1223–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.S.; Franco, S.J.; Muller, U. Extracellular Matrix: Functions in the Nervous System. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 3, a005108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vieira, M.S.; Santos, A.K.; Vasconcellos, R.; Goulart, V.A.M.; Parreira, R.C.; Kihara, A.H.; Ulrich, H.; Resende, R.R. Neural Stem Cell Differentiation into Mature Neurons: Mechanisms of Regulation and Biotechnological Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1946–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Dityatev, A. Crosstalk between Glia, Extracellular Matrix and Neurons. Brain Res. Bull. 2018, 136, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J.W.; Oohashi, T.; Pizzorusso, T. The Roles of Perineuronal Nets and the Perinodal Extracellular Matrix in Neuronal Function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, A.E.J.; Burbach, J.P.H.; Hol, E.M. Cell Adhesion and Matricellular Support by Astrocytes of the Tripartite Synapse. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018, 165-167, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, L.S.; Barrón, E.; Saperia, D.; Chui, H.C. Association between Vascular Basement Membrane Components and the Lesions of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 1991, 30, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Rodriguez, M.; Perez, S.E.; Nadeem, M.; Malek-Ahmadi, M.; Mufson, E.J. Frontal Cortex Chitinase and Pentraxin Neuroinflammatory Alterations during the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neuroinflam. 2020, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Reddy, D.S. Integrins as Receptor Targets for Neurological Disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 134, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dityatev, A.; Schachner, M. Extracellular Matrix Molecules and Synaptic Plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dityatev, A.; Schachner, M.; Sonderegger, P. The Dual Role of the Extracellular Matrix in Synaptic Plasticity and Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, C.M.; Lynch, G. Integrins, Synaptic Plasticity and Epileptogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2004, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, C.M.; Pinkstaff, J.K.; Lauterborn, J.C.; Xie, Y.; Lynch, G. Integrins Regulate Neuronal Neurotrophin Gene Expression through Effects on Voltage-Sensitive Calcium Channels. Neuroscience 2003, 118, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Jardón, M.; Klapproth, S.; Gimeno-LLuch, I.; Petzold, T.; Bharadwaj, M.; Müller, D.J.; Zuchtriegel, G.; Reichel, C.A.; Costell, M. The Fibronectin Synergy Site Re-Enforces Cell Adhesion and Mediates a Crosstalk between Integrin Classes. eLife 2017, 6, e22264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Carraher, C.; Schwarzbauer, J.E. Assembly of Fibronectin Extracellular Matrix. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 26, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mönning, U.; Banati, R.B.; Masters, C.L.; Sandbrink, R.; Weidemann, A.; Beyreuther, K. Extracellular Matrix Influences the Biogenesis of Amyloid Precursor Protein in Microglial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 7104–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hawkes, C.A.; Härtig, W.; Kacza, J.; Schliebs, R.; Weller, R.O.; Nicoll, J.A.; Carare, R.O. Perivascular Drainage of Solutes Is Impaired in the Ageing Mouse Brain and in the Presence of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 121, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, D.E.; Dudai, Y. MAPK Cascades in the Brain: Lessons from Learning. In MAP Kinase Signaling Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 205, pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Kim, N.-J. Recent Advances in the Inhibition of P38 MAPK as a Potential Strategy for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. A J. Synth. Chem. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2017, 22, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perea, J.R.; Ávila, J.; Bolós, M. Dephosphorylated rather than Hyperphosphorylated Tau Triggers a Pro-Inflammatory Profile in Microglia through the P38 MAPK Pathway. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 310, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, E.; Lloret, A.; Fuchsberger, T.; Viña, J. Aβ and Tau Toxicities in Alzheimer’s are Linked via Oxidative Stress-Induced P38 Activation: Protective Role of Vitamin E. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gee, M.S.; Son, S.H.; Jeon, S.H.; Do, J.; Kim, N.; Ju, Y.-J.; Lee, S.J.; Chung, E.K.; Inn, K.-S.; Kim, N.-J.; et al. A Selective P38α/β MAPK Inhibitor Alleviates Neuropathology and Cognitive Impairment, and Modulates Microglia Function in 5XFAD Mouse. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maiese, K. Forkhead Transcription Factors: New Considerations for Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. J. Transl. Sci. 2016, 2, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shang, Y.; Chong, Z.; Hou, J.; Maiese, K. FoxO3a Governs Early Microglial Proliferation and Employs Mitochondrial Depolarization with Caspase 3, 8, and 9 Cleavage during Oxidant Induced Apoptosis. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2009, 6, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Ho, M.S.; Xue, L. FoxO Mediates APP-Induced AICD-Dependent Cell Death. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, C.; Viccaro, K.; Lee, H.; Shah, K. Cdk5-FOXO3a Axis: Initially Neuroprotective, Eventually Neurodegenerative in Alzheimer’s Disease Models. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1815–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brunet, A.; Datta, S.R.; Greenberg, M.E. Transcription-Dependent and -Independent Control of Neuronal Survival by the PI3K–Akt Signaling Pathway. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2001, 11, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwood, J.M.; Dufour, F.; Laroche, S.; Davis, S. Signalling Mechanisms Mediated by the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Cascade in Synaptic Plasticity and Memory in the Rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 23, 3375–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-C.; Wang, L.; Xie, Z.; Yau, A.; Zhong, Y. PI3 Kinase Signaling Is Involved in a -Induced Memory Loss in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7060–7065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schäbitz, W.-R.; Krüger, C.; Pitzer, C.; Weber, D.; Laage, R.; Gassler, N.; Aronowski, J.; Mier, W.; Kirsch, F.; Dittgen, T.; et al. A Neuroprotective Function for the Hematopoietic Protein Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF). J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007, 28, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.-K.; Kumar, P.; Fu, Q.; Rosen, K.M.; Querfurth, H.W. The Insulin/Akt Signaling Pathway Is Targeted by Intracellular β-Amyloid. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009, 20, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Chiang, H.-C.; Wu, W.; Liang, B.; Xie, Z.; Yao, X.; Ma, W.; Du, S.; Zhong, Y. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Is a Preferred Target for Treating Amyloid-β-Induced Memory Loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16743–16748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.-J.; Her, G.M.; Hu, M.-K.; Chen, Y.-W.; Tung, Y.-T.; Wu, P.-Y.; Hsu, W.-M.; Lee, H.; Jin, L.-W.; Hwang, S.-P.; et al. ErbB2 Regulates Autophagic Flux to Modulate the Proteostasis of APP-CTFs in Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3129–E3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birecree, E.; Whetsell, W.O.; Stoscheck, C.; King, L.E.; Nanney, L.B. Immunoreactive Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors in Neuritic Plaques from Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1988, 47, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, G.; Cohen, S. Epidermal Growth Factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 7709–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-S.; Chen, W.-Y.; Yin, J.J.; Sheppard-Tillman, H.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.-N. EGF Receptor Promotes Prostate Cancer Bone Metastasis by Downregulating MiR-1 and Activating TWIST1. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 3077–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kirouac, L.; Rajic, A.J.; Cribbs, D.H.; Padmanabhan, J. Activation of Ras-ERK Signaling and GSK-3 by Amyloid Precursor Protein and Amyloid Beta Facilitates Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. eNeuro 2017, 4, ENEURO.0149-16.2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).