1. Introduction

Mitochondrial disorders are a large group of severe genetic disorders that primarily impact cells and tissues with high energy requirements [

1,

2]. These disorders are clinically complex, often fatal, and occur at an estimated ratio of 1 in 10,000–15,000 live births [

3,

4]. Leigh syndrome (LS) is a classic mitochondrial disorder that is the result of deleterious mtDNA mutations that disrupt the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) capacities of cells that are impacted [

4]. Presently, there is very little evidence of targeted therapies for LS [

4,

5]. Recent studies has highlighted the potential for cell-permeant substrates regulating the electron transport chain (ETC) as therapeutics for mitochondrial diseases [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These substrates work by increasing tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) intermediates and providing alternative substrate sources for energy production in the mitochondria. One of the mitochondrial substrates that is currently being explored as a therapeutic option for LS is succinate [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Conversion of succinyl-CoA by the enzyme succinyl-CoA synthetase yields free succinate as an intermediate substrate of the TCA cycle, to form GTP which further donates its terminal phosphate group to ADP to form ATP [

14]. Succinate is further dehydrogenated to fumarate by the flavoprotein succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), which is tightly embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane. SDH, also known as complex II, contains a covalently bound Flavin adenine nucleotide (FAD) which gets simultaneously reduced to FADH

2. In turn, FADH

2 contributes to the ETC by reducing ubiquinone (CoQ) to ubiquinol (CoQH

2). CoQ functions as an electron carrier and transfers electrons to complex III [

15]. Succinate is presumed to represent one of the major sources of electrons for mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), when it is oxidized by the ETC to reduce oxygen to superoxide [

16]. Succinate also contributes to the elimination of superoxide and H

2O

2 production [

17,

18], suggesting that complex II could be an important contributor for regulating ROS homeostasis. Thus, SDH couples two major pathways in the mitochondria, the TCA cycle and the ETC, both being essential for oxidative phosphorylation [

19].

In healthy mitochondria, CI-linked respiration is largely responsible for ETC activity and subsequent ATP production by complexes I, III, IV, and V [

15]. Consequently, inhibition of complex I (CI) activity can interfere with the majority of ATP production in the mitochondria. Chronic CI dysfunction leads to the disruption of NADH oxidation and cells try to compensate for the reduced NAD levels, by increasing pyruvate which gets converted to lactate, and thereby maintaining the NAD pool in the cells. Succinate offers an alternate metabolic pathway, bypassing CI-linked respiration in the case of CI defect.

Succinate is a dicarboxylic acid that takes the form of an anion in living organisms. As such, it is not cell membrane permeable and has limited uptake into cells when given exogenously [

9]. To overcome this limitation, prodrugs of succinate have been developed and screened for cell permeability [

9]. NV101-118 (NV118, diacetoxymethyl succinate), hereafter referred to as NV118, is one of the successful cell membrane-permeable prodrugs of succinate that was recently developed [

9]. Since its development, NV118 has been explored as a potential therapeutic for various diseases [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

20]. NV118 is currently being tested for its therapeutic potential in various cellular models of diseases associated with CI dysfunction [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

20]. In all of these models, NV118 improved mitochondrial function, as evidenced by increased CII-linked respiration, membrane potential, ATP production, and a decrease in lactic acidosis [

9,

11,

20]. Furthermore, recent studies have shown improvement in mitochondrial respiration with NV118 in cellular models with inhibition of downstream ETC enzymes such as CIV [

12,

13]. These studies suggest that NV118 can improve mitochondrial respiration by other means aside from elevating CII activity.

In earlier studies in our laboratory, we reported fragmented/hyper fused mitochondrial morphology [

21], abnormal ETC enzymatic activity, depressed mitochondrial function, decreased ROS, and membrane potential in fibroblast cells modeling LS. Two LS fibroblast cell lines harbored pathogenic point mutation in the mtDNA at

T8993G in the

MTATP6 gene causing complex V deficiency, while the third LS fibroblast cell lines harbored pathogenic point mutation in the mtDNA at

T10158C in the

MTND3 gene and the fourth LS fibroblast cell lines harbored pathogenic point mutation in the mtDNA at

T12706C in the

MTND5 gene causing complex I deficiency. A commercially available fibroblast cell line (BJ-FB) was used as a healthy control line.

In the present study, we used the same fibroblast cells modeling LS and the control BJ cell line and treated them for 24 h with varying concentrations of NV118 to measure changes in mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. Our results suggest that 24-hour treatment with 100 µM of NV118 can rescue some of the mitochondrial dysfunction in treated LS cells as compared with untreated cells. We report, for the time, that after a 24-hour treatment with 100 µM of NV118, cellular bioenergetics improved as a result of upregulation of glycolysis, TCA cycle, and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). We show that the most sustained change was in glycolysis, as mitochondrial respiration remained the same after 24-hour treatment with NV118. Together, our results suggest that NV118 could serve as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of LS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

This study protocol conformed to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The current study was conducted with patient fibroblasts provided by the Medical University of Salzburg (SBG), Austria. Fibroblasts were obtained for diagnostic purposes from patients with defined disorders. Informed consent was obtained to use these samples for research in an anonymized way. In accordance with federal regulations regarding the protection of human research subjects (32 CFR 219.101(b)(4)), the University of Arkansas Office of Research Compliance determined that the project was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight and human research subject protection regulations.

2.2. NV118 Drug Preparation

The NV118 succinate prodrug (Oroboros Instruments Corporation, Innsbruck, Austria) was prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions. Aliquots of the stock were stored in a −20 °C freezer until needed for experiments. Before each experiment, a fresh working solution was prepared by adding the appropriate volume of stock solution to phenol red-free MEM. The working solution (1 mM) was prepared at 10X the final treatment concentration (100 µM). The working solutions were used up on the same day as they were prepared.

2.3. Cell Culture

Cultures of healthy control and four patient-derived diseased fibroblast cell lines were maintained in a fibroblast expansion medium that consisted of minimal essential medium (MEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GE Healthcare HyCloneTM, Chicago, IL, USA) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cell lines were cultured and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The culture medium was replenished every two days and passaged when cells reached 80% confluence. Fibroblasts were enzymatically passaged in 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All experiments were performed with cells at Passage 8 for consistency and to minimize experimental variability.

2.4. Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption Detection, Glycolysis Function Test, and Bioenergetics Health Index

Cells were routinely maintained in culture following established protocols until the desired passage (Passage 8) was reached. A day before assay, 20,000 cells per well were plated and cultured in complete medium (MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine). Prior to treatment, the drug treatment group had 100 μM of NV118 in basal MEM (without FBS) added to each well, while the control groups had an equivalent volume of basal MEM (without FBS) added to each well. The cells were incubated with NV118 in MEM (or basal MEM) in a 37 °C incubator with a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 24 h. At the end of the 24-hour incubation period, mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolic profiles were assessed following the steps below.

Changes in oxygen consumption were measured in real time using an XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer. A Seahorse XFe96 Cell Mito Stress Test Kit and glycolytic rate assay kit (Seahorse Biosciences, North Billerica, MA, USA) were used, as per the manufacturers’ instructions. Prior to use in XFe96, fibroblasts were detached using mild trypsin and seeded into the plates with a previously optimized number of 20,000 cells per well. All fibroblasts were seeded in 8–12 replicate wells per plate, with the experiment repeated at least 3–5 times.

The cells were supplemented with 180 μL Mito stress complete Seahorse medium, after which the cells were incubated in a non-CO2 incubator at 37 °C for one hour. Respiration was measured using the classic mitochondrial inhibitors, specific for complex I and III subunits, such as rotenone and antimycin A (0.5 μM final concentrations each). Maximum respiration was measured by the addition of an uncoupler carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (0.7 μM final concentration) and oligomycin (1 μM final concentration) was added to measure proton leak. The readouts were normalized to cell numbers and analyzed using Seahorse XF96 Wave software.

We also analyzed glycolytic function in the fibroblast cell lines. A classical glycolytic rate assay was performed using the XFe96 based on the following procedure: (1) cells were cultured in buffered (5 mM HEPES buffer) Seahorse medium supplemented with glucose and pyruvate, (2) the proton efflux rate (PER) was measured after the addition of saturating amounts of glucose, (3) rotenone and antimycin A were added to inhibit mitochondrial-derived ADP phosphorylation, and (4) 2-DG was added to inhibit glycolysis. The different assay parameters, i.e., basal glycolysis, compensatory glycolysis, total proton efflux, and post 2-DG acidification, were normalized to cell number and analyzed using Seahorse XFe96 Wave software.

The mitochondrial-derived bioenergetic health index (mitoBHI), a composite index of mitochondrial quality was determined using the predefined formula: . The glycolytic BHI (glycoBHI), an index of glycolytic respiration was determined using the formula: .

2.5. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurements

Cells were maintained in culture following established protocols until the desired passage (Passage 8) was reached. When cells reached 80–85% confluence, they were treated with either 100 μM of NV118 or an equivalent volume of basal MEM (FBS free) and incubated for 24 h. After the 24-hour incubation, mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated following the procedure below.

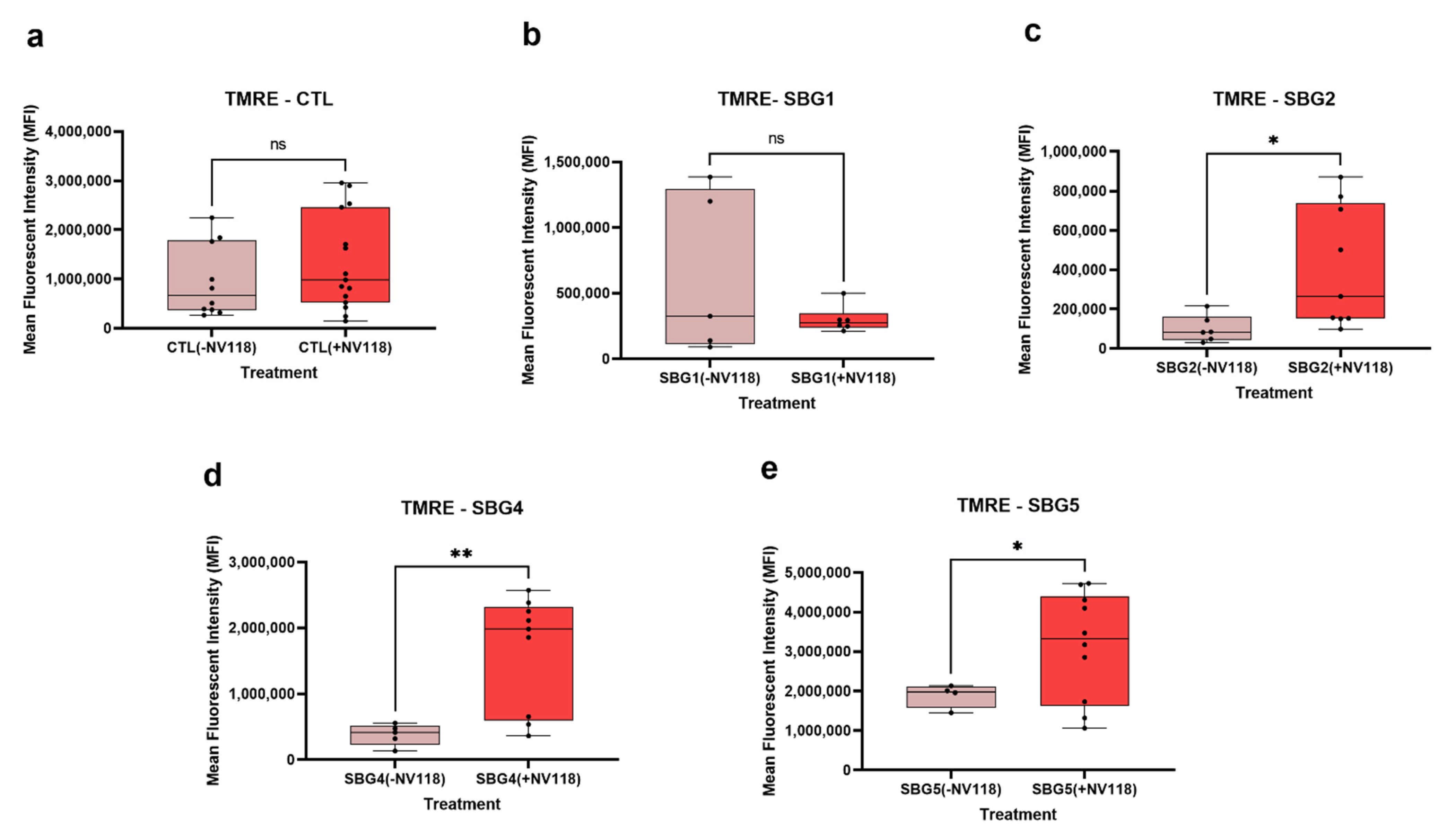

On the day of the experiment, cells were enzymatically detached using 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and centrifuged at 400× g for 5 min. Then, the cells were resuspended in basal medium, after which the desired amount of tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was added (for a final concentration of 50 nM). For the FCCP and oligomycin treatment groups, 20 µM and 5 µM of FCCP and oligomycin were added, respectively, for 10 min prior to treatment with TMRE. Cells were incubated with TMRE in a 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator for 25 min. At the end of the incubation period, cells were centrifuged at 400× g for 5 min. To wash off the excess dye, cells were resuspended in 1× dPBS solution and centrifuged for another 5 min. At the end of the wash, the cells were resuspended in phenol red-free basal medium and transferred to Accuri C6 plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for data acquisition. 20,000 events were recorded for each cell line. After data acquisition, the data were exported as FCS files and analyzed using FlowJo_v10.6.2 software. To gate for the TMRE-positive population, cells that were not stained with TMRE were used to gate for the TMRE negative cell populations. The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) values, a measure of the geometric mean of TMRE positive cells was obtained for statistical analysis.

2.6. Intracellular ROS Measurement

Cells were maintained in culture following established protocols until the desired passage (Passage 8) was reached. A day before assay, 20,000 cells per well were plated and cultured in complete medium (MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine). In addition, the treatment groups had either 100 μM NV118 or an equivalent volume of basal MEM (FBS free) in each well. After 24 h, the intracellular ROS levels were measured using the 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA/H2DCFDA) a cell-permeable cellular ROS assay kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). This dye measures hydroxyl (-OH), peroxyl (O22-), and other reactive oxygen species (ROS). Within the cells, DCFDA is hydrolyzed by nonspecific esterases to release DCF, which is readily oxidized by intracellular ROS. The oxidized product emits green fluorescence at (Ex/Em = 485/535). Following the manufacturer’s instructions, the cells were incubated with 10 μM of DCFDA. The cells were incubated in the dark for 45 min with this dye. As a positive control, 200 μM of TBHP was added for 60 min before DCFDA treatment. At the end of the incubation period with DCFDA, the cells were washed once with phenol red-free MEM to get rid of the excess dye. Finally, phenol red-free MEM was added to each well, and cells were transferred to a plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) for data acquisition. The fluorescent intensity was background corrected and adjusted by subtracting fluorescent intensity from blank wells.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

In order to ensure scientific rigor and reproducibility, for the bioenergetics analysis, an ANOVA design accounting for 4–5 biological and 10–12 technical replicates from the control (BJ-FB) and diseased (SBG1-FB, SBG2-FB, SBG4-FB, and SBG5-FB) cells that were nested within treated and untreated groups was used to identify any differences with respect to control BJ-FBs. Post hoc Tukey HSD tests were used to identify differences among specific groups. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Similarly, for the ROS analysis, an ANOVA design accounting for 3 biological and 10–12 technical replicates from control (BJ-FB) and diseased (SBG1-FB, SBG2-FB, SBG4-FB, and SBG5-FB) cells that were nested within treated and untreated groups was used to identify any differences with respect to control BJ-FBs. Post hoc Tukey HSD tests were used to identify differences among specific groups. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

For the MMP analysis, an ANOVA design accounting for 3 biological and 3–4 technical replicates from control (BJ-FB) and diseased (SBG1-FB, SBG2-FB, and SBG4-FB, SBG5-FB) cells that were nested within treated and untreated groups was used to identify any differences with respect to the control BJ-FB. Post hoc Tukey HSD tests were used to identify differences among specific groups. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

4. Discussion

To date, there is no cure for patients affected with LS, with fatality in patients usually within a decade after their initial diagnosis [

33,

34]. Recently, cell-permeant ETC substrates have been proposed as therapeutics for various ETC defects [

9,

10]. In these studies, succinate prodrugs have been used as a bypass for disorders involving deficiencies in complex I. The succinate prodrugs have also been used to rescue mitochondrial disorders associated with a defect in complex IV, an ETC complex whose activity is downstream of that of complex I [

12,

13]. It is important to note that these studies have looked at acute effects of NV118 treatment to improve respiration and have not fully examined the long-term effects of NV118 on different biochemical deficiencies. So far, none of the studies have used succinate prodrugs for alleviating symptoms of LS harboring pathogenic mtDNA mutations in the

MTATP6 gene affecting complex V and the

MTND3 and

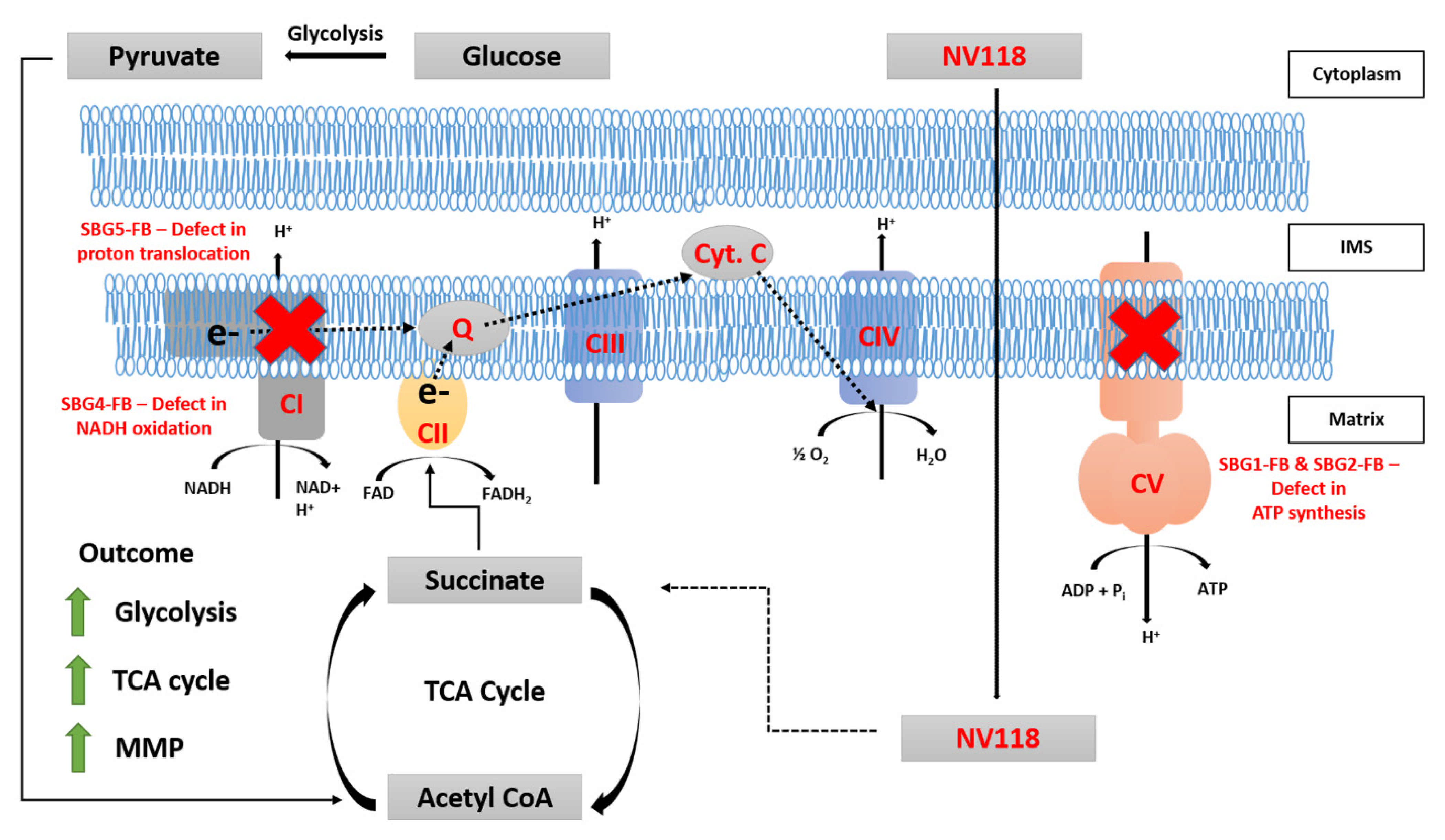

MTND5 genes affecting complex I. Therefore, we wanted to understand the mechanisms (

Figure 6) as well as alleviate the bioenergetic defects by providing succinate, as a therapeutic drug (NV118) in the vulnerable LS cell lines containing pathogenic mtDNA mutations affecting complexes I and complex V. In addition, our study focused on evaluating the medium/long term effects of NV118, which allowed us to better distinguish the direct and indirect effects upon NV118 treatment, without increasing the risk of ROS production.

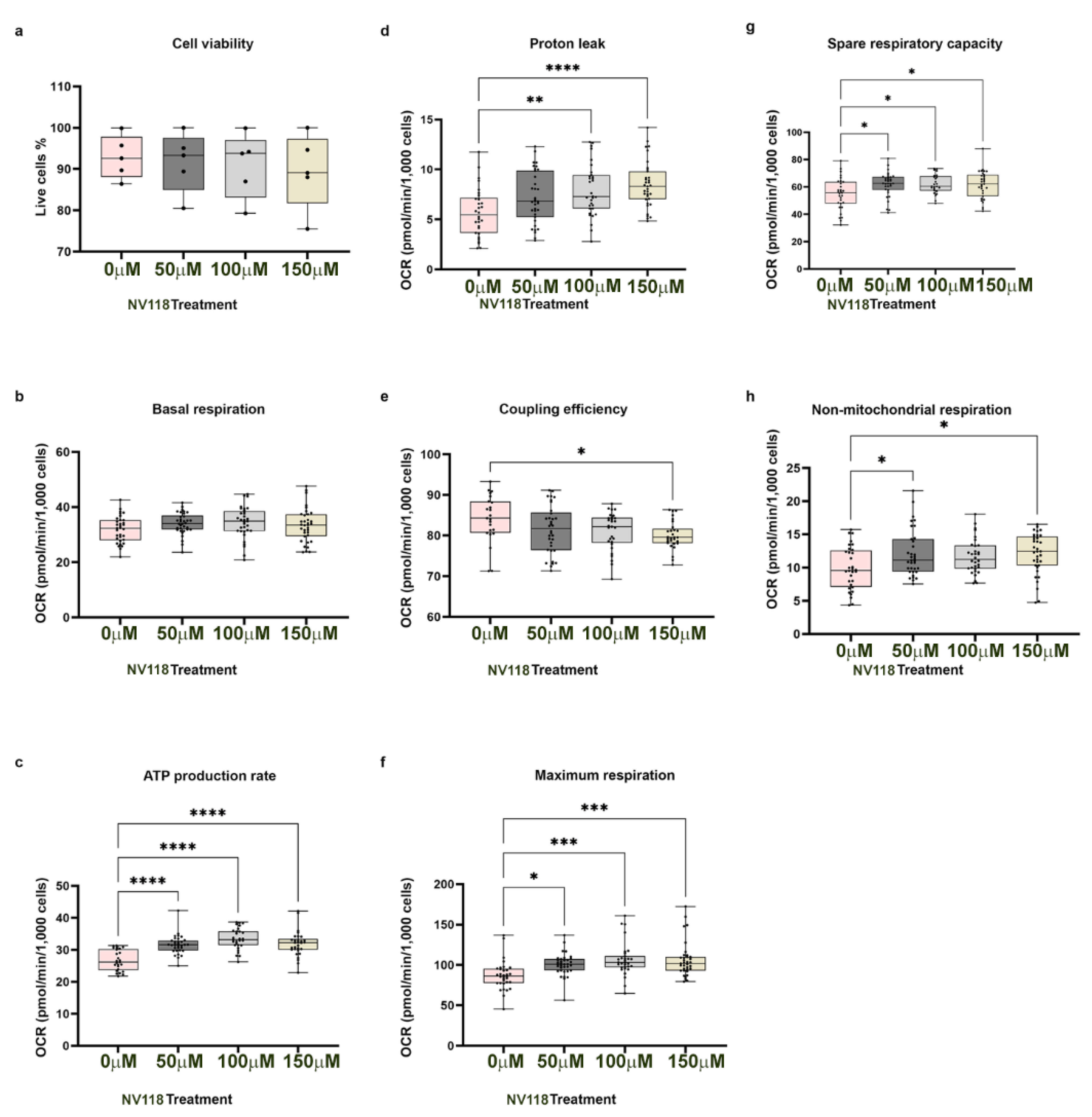

It has been reported previously that high concentrations of succinate exert inhibitory effects on mitochondrial respiration [

19,

28]. Furthermore, high concentrations of succinate could result in upregulation of RET, contributing to an increase in ROS production and subsequent cellular apoptosis [

19,

26,

27]. Therefore, optimization experiments for estimating drug toxicity were performed in control BJ-FB cells. The addition of different concentrations of NV118 (50, 100, and 150 μM) to the BJ-FB cells showed that the 50 μM and 100 μM NV118 treatment groups led to a 1% and 2% decrease in cell viability, respectively, while 150 mM led to a 4% decreased in cell viabilityas compared with the non-treated group. These results led us to conclude that 100 μM of NV118 would be tolerated by the disease lines as well, and therefore was used in subsequent respiration experiments. We observed the highest increase in ATP production in the group treated with 100 μM of NV118, which correlated with a significant increase in maximal respiration and SRC as well. It is worth noting that some of the increases in oxygen consumption with higher concentrations of NV118 (150 μM), contributed to a dose-dependent elevation of proton leak and lowered coupling efficiency in control BJ-FB relative to the untreated group. Therefore, 150 μM of NV118 was not selected for further studies. Together, the cell viability and the mitochondrial respiration studies convinced us that 100 μM of NV118 was the optimal concentration for evaluating the effects of the drug on mitochondrial function.

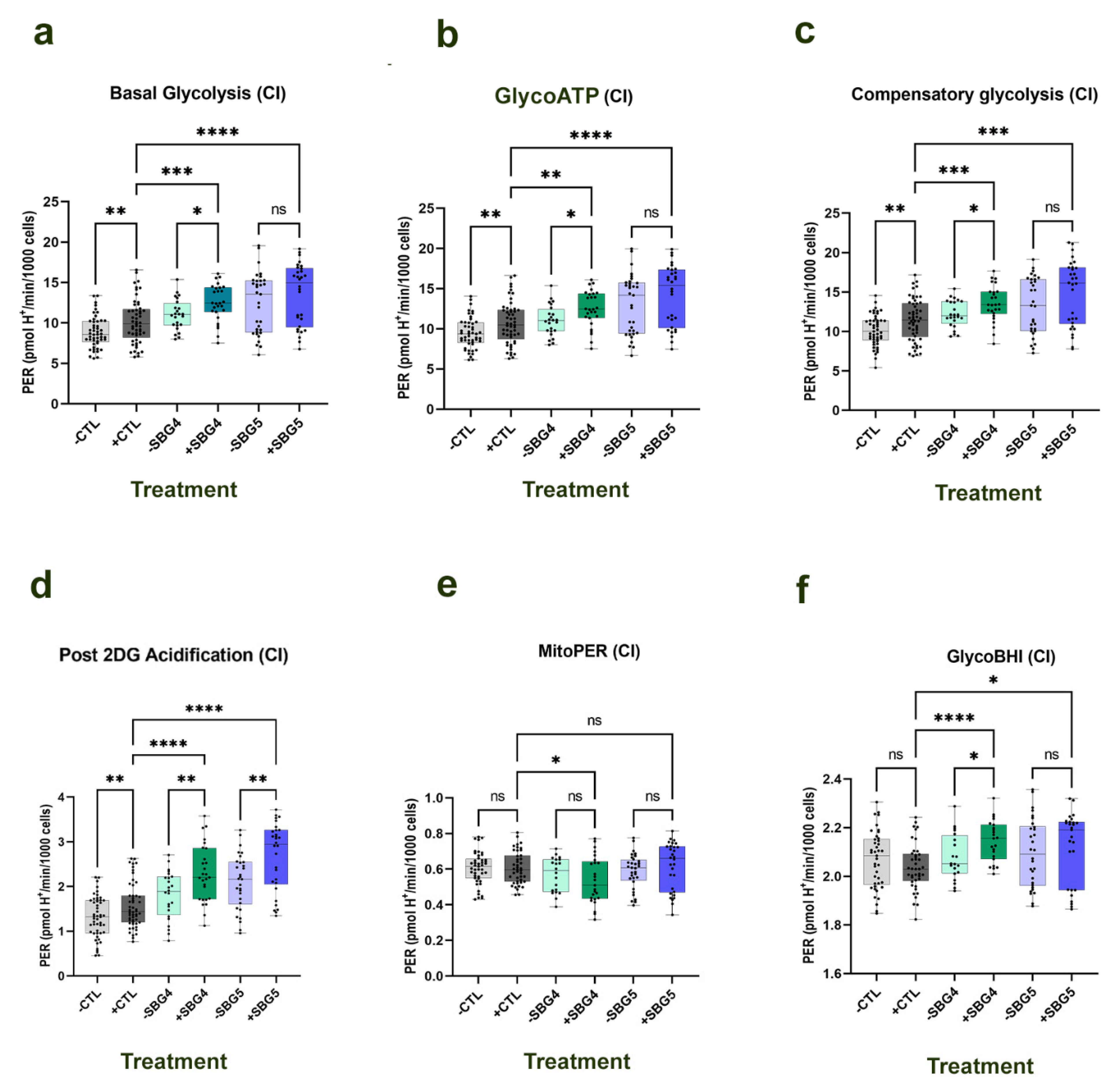

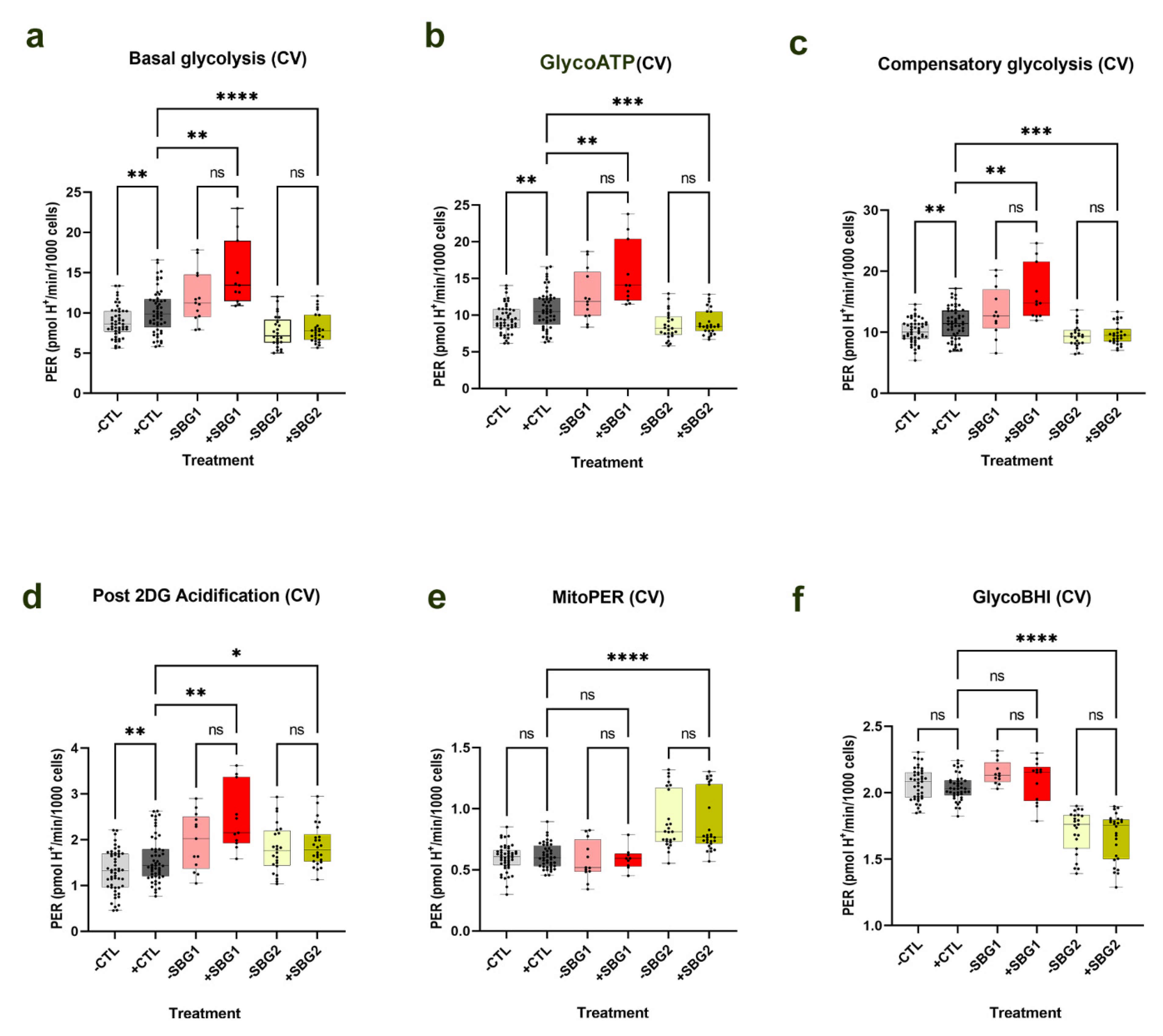

The results of the respiration experiments in BJ-FB indicated a significant increase (by 18%,

p < 0.05) in nonmitochondrial respiration in cells treated with 100 μM of NV118 as compared with the untreated group. Nonmitochondrial respiration is typically attributed to the non-ETC oxidase present in the cell [

22], suggesting reduced involvement of non-ETC oxidases. Subsequently, glycolysis was evaluated after a 24-hour treatment with 100 μM of NV118. In the TCA cycle, oxidation of succinate results in the production of fumarate. Fumarate is further oxidized to malate, and malate becomes oxidized to produce oxaloacetate. In the absence of succinate, succinate dehydrogenase (SDH CII) is inhibited and deactivated by oxaloacetate [

31,

35,

36]. As a prodrug of succinate, the addition of NV118 for 20 min resulted in a short-term increase in CII respiration, which could result in accumulation of TCA cycle intermediates upstream of succinate. One of those intermediates is oxaloacetate (OAA), and if not used up it continues to accumulate, and could result in inhibition of CII activity. Therefore, we hypothesized that the addition of NV118 would result in the upregulation of glycolysis. In support of this hypothesis, upon NV118 treatment, we observed a significant increase (

p < 0.05) in basal glycolysis and glycoATP production rate in the control BJ-FB and the LS SBG4-FB (

T10158C) cell line with complex I defect, with an upward trend in glycolytic respiration in the other LS cell lines, SBG1-FB (

T8993G), SBG2-FB (

T8993G), and SBG5-FB (

T12706C). When glycolysis was inhibited with 2-deoxyglucose (2DG), there was a significant increase (

p < 0.01) in the control BJ-FB and a trend towards an increase in post 2DG acidification in all the diseased FB cell lines. Since the addition of 2DG inhibits glycolysis, it prevents lactate from being formed. However, during cellular respiration, the CO

2 produced during oxidation reactions by TCA cycle dehydrogenases contributes to further acidification [

35,

36]. This further supports the hypothesis that NV118 upregulates glycolysis to enhance the production of other TCA cycle substrates.

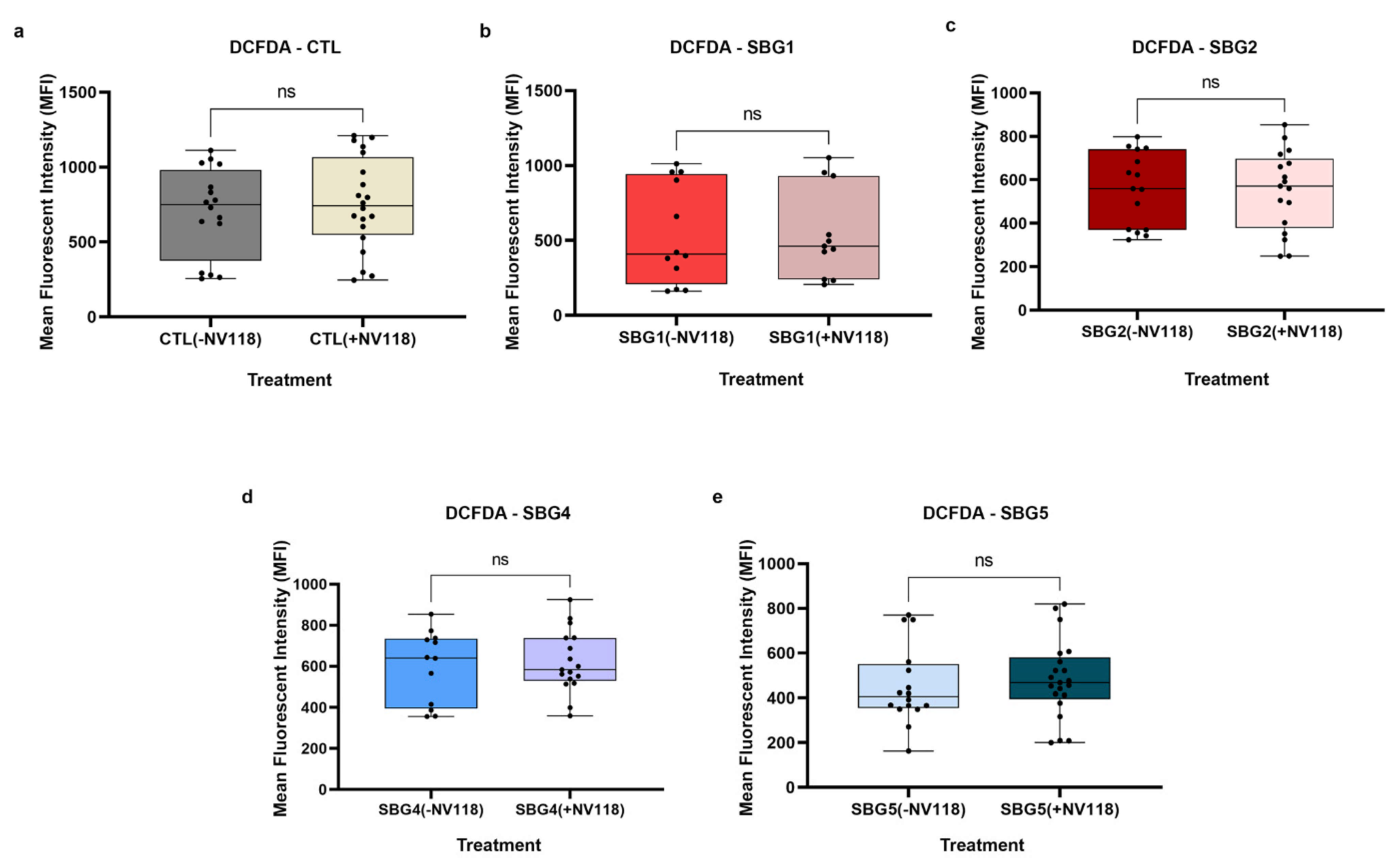

It is well known that reverse electron transport (RET) via complex I and NAD

+ dependent pathways occurs when there is an overreduction of the CoQ pool by electrons from CII [

25,

26,

27,

37]. To exclude the possibility that the treatment with NV118 was causing RET and contributing to reactive oxygen species production, we examined intracellular ROS levels using DCFDA/H

2DCFDA, a fluorescent precursor, after 24-hour treatment with 100 µM of NV118. This dye measures hydroxyl, peroxyl, and other ROS within cells. DCFDA is hydrolyzed by esterases to release DCF, which is readily oxidized by intracellular ROS, thus, emitting a green fluorescence (Ex 475/Em 515). The results from the ROS studies supported the observations made during the optimization studies with control BJ-FB cells. The treatment with 100 µM of NV118 did not result in a significant difference in intracellular ROS levels in any of the cell lines between the NV118 treated and untreated groups. The intracellular ROS levels observed in this study are consistent with our previous results, where LS diseased cell lines exhibited lower mitoROS levels as compared with the control BJ-FB cells (

Supplementary Materials Figure S10). We conclude that the specific concentration of (succinate) produg NV118 used in this study did not contribute to complex I and NAD

+ mediated reverse electron transport (RET) or increase intracellular ROS levels in either the control or LS cell lines.

Knowing that the increase in CII respiration did not result in elevated RET or ROS levels, next, we examined the MMP levels in the control and diseased FB in the presence and absence of prodrug NV118. As expected, we observed a significant increase (

p < 0.05) in MMP levels in both complex I defective LS (SBG4-FB (

T10158C) and SBG5-FB (

T12706C)) cells upon NV118 treatment as compared with the untreated group. We also observed a significant increase (

p < 0.05) in MMP levels in SBG2-FB (

T8993G) with CV defect after NV118 addition. In the control BJ-FB cells, treatment with NV118 led to a 39% increase (although not significant) in MMP levels relative to the untreated cells. In the SBG1-FB (

T8993G), the MMP levels stayed the same in both the NV118 treated and untreated groups. When we supplemented cells with uncouplers (FCCP) and ATPase inhibitor (oligomycin) to both treated and untreated groups to depolarize and hyperpolarize MMP, respectively, FCCP resulted in depolarization, as predicted. Interestingly, supplementation of NV118 to SBG2-FB (

T8993G) cells, rescued the mitochondrial defect. We have reported previously that SBG2-FB (

T8993G) has an additional uncoupling defect [

21]. However, addition of exogenous substrate (NV118) allowed for complete depolarization (significant decrease in MMP,

p < 0.001) when cells were supplemented with the uncoupler FCCP. When oligomycin was added, we predicted hyperpolarization in the NV118 untreated group. The results showed that all of the cell lines in the treated group, except SBG1-FB (

T8993G), exhibited membrane depolarization instead of hyperpolarization. Since oligomycin is an ATPase inhibitor, it could eliminate the influence of mitochondrial ATP hydrolysis due to the decrease observed in membrane potential [

38]. In intact cells, all mitochondria possess an endogenous proton leak, which may serve an important purpose in completing the proton circuit in the absence of ATP synthesis [

39]. This could plausibly explain the depolarization of the membrane observed in this study.

In quantifying mitochondrial respiration to check if the increased MMP corresponded with increased OCR levels, we observed that mitochondrial respiration was unchanged after 24-hour treatment with NV118. However, in our optimization studies with NV118 for 20 min in the control BJ-FB cells, the OCR measurements showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in mitoATP production, maximal respiration, and SRC rates. Therefore, this surprising result shows that the 20-minute treatment with NV118 can result in a transient increase in mitochondrial respiration, while the 24-hour treatment resulted in no change in mitochondrial respiration in all cell lines. It is possible that a 24-hour treatment with prodrugs NV118 led to increased TCA cycle substrates. Alternately, there was an initial increase in flux to produce ATP, which was transported out into the cytoplasm by unknown mechanisms to increase glycolysis and maintain the energy requirement of the cells. What we observed after the 24-hour treatment was an increase in aerobic and an increase in the MMP levels that corresponded to the effect of the 100 μM concentration of the prodrug NV118. The results from this study suggest other mechanisms of action for the succinate prodrug NV118. Ongoing studies in our laboratory are focused on metabolomic analyses to further provide information on the mechanisms of action of energy maintenance pathways and the role of TCA-cycle metabolites in these cell lines.

Other studies using NV118 as a therapy for CI-deficient cells, have suggested that the drug works by bypassing CI and upregulating CII respiration [

9,

11,

20]. While this explanation is valid in cell lines with CI deficiencies, other labs have also shown improvement in mitochondrial function in cells with deficiencies in other ETC enzymes downstream of CI [

12,

13]. In this study, bypassing CI with NV118 does not fully explain how the disease phenotype is rescued in cells exhibiting CI and CV deficiencies. The results from this study indicate upregulation of glycolysis and an increase in MMP without increasing intracellular ROS levels.

It has been demonstrated elsewhere that activated macrophages undergo metabolic alterations to support their proinflammatory functions [

40]. In these studies, stimulation of macrophages with LPS (lipopolysaccharides), endotoxins found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, resulted in a switch to succinate-dependent respiration, and a subsequent increase in glycolysis and MMP. In macrophages, the increased succinate oxidation resulted in ROS production and production of proinflammatory cytokines. While the addition of prodrug NV118 did not increase intracellular ROS levels in LS cell lines, we observed similar increases in aerobic glycolytic flux and MMP, consistent with other studies [

40]. We postulate that the addition of succinate (NV118) increases glycolysis over a 24-hour period to prevent the accumulation of oxaloacetate (a potent inhibitor of CII) [

31,

41]. The trend towards increased MitoPER and elevated post 2DG acidification in most of the cell lines in the presence of NV118, further supports this hypothesis. Since CO

2 from the TCA cycle can contribute to acidification [

35], when glycolysis is inhibited by 2DG, the other source of acidification could be from the TCA cycle. Upregulation of glycolysis by NV118 increases TCA cycle intermediates (

Figure 6) and also contributes to ATP production [

42]. It is useful to note that succinate itself is a product of a substrate-level phosphorylation step in the TCA cycle [

19]. Therefore, increasing TCA cycle intermediates could help provide additional ATP in cell lines with mutations affecting OXPHOS capacities.

LS is a disorder with no known cure. According to the results from this study, we have also shown, for the first time, that in addition to rescuing mitochondrial dysfunction in cell lines with mutations impacting CI, NV118 has the potential to rescue mitochondrial dysfunction in cell lines with mutations impacting CV (ATP synthase). Although previous studies have focused on improving mitochondrial respiration, we show, here, that perhaps instead of trying to improve OXPHOS capacities in patients with LS, alternate therapies that focus on providing important TCA cycle intermediates could prove to be more beneficial. This is the first study that shows a beneficial effect in four LS lines harboring mtDNA mutations (

T8993G,

T10158C, and

T12706C) without increasing the risk of ROS production in the 24-hour exposure to NV118. Since there was no observed change in ROS production between control and LS-FBs, it indicates that the optimal concentration of NV118 should be well tolerated in cells/tissues of patients with LS. Other studies have, however, shown that by exposing cells to saturating levels of succinate, a part of the electron flow is reversed leading to RET and increased generation of mitochondrial ROS [

43]. In the context of possible treatment options for LS, we have shown that increasing glycolysis is important because glucose metabolism produces useful intermediates for other metabolic pathways, such as synthesis of amino acids or fatty acids. An interesting aspect of glycolysis and NV118 is that upon NV118 hydrolysis, formaldehyde is released which, at high concentration, has an inhibitory effect on glycolysis [

44]. However, in our studies, we have demonstrated that the optimized 100 μM of NV118 exposure for 24 h with minimal effect on cell viability and ROS does not appear to inhibit glycolysis. Our study has also demonstrated an improvement in mitochondrial function, based on an increase in MMP upon NV118 treatment. Taken together, these results point to a potential therapeutic effect of NV118 for LS. Therefore, a better understanding of the dynamic nature of metabolic compensatory mechanisms is important to address in the context of developing novel therapeutic strategies for primary mitochondrial diseases such as LS [

45].

The results from this study have opened an avenue for further questions to be addressed in the future. For instance, what intervals of treatment are ideal to observe the full beneficial effect of NV118 in LS patients? In this study, all the LS cell lines used were derived from patients with early-onset LS. Clinical reports and metadata analysis are starting to suggest a difference in disease presentation and prognosis for patients with early-onset and late-onset LS [

46,

47]. Perhaps, including cell lines derived from patients with late-onset LS presentation could provide insights into how late-onset LS disease would respond to prodrug NV118 treatment. Nevertheless, this is the first study showcasing a single therapeutic dose of NV118 in LS patient cells harboring pathogenic mtDNA mutations in the

MTATP6,

MTND3, and

MTND5 genes affecting complexes I and V of the electron transport chain.