Mitochondrial Cyclosporine A-Independent Palmitate/Ca2+-Induced Permeability Transition Pore (PA-mPT Pore) and Its Role in Mitochondrial Function and Protection against Calcium Overload and Glutamate Toxicity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

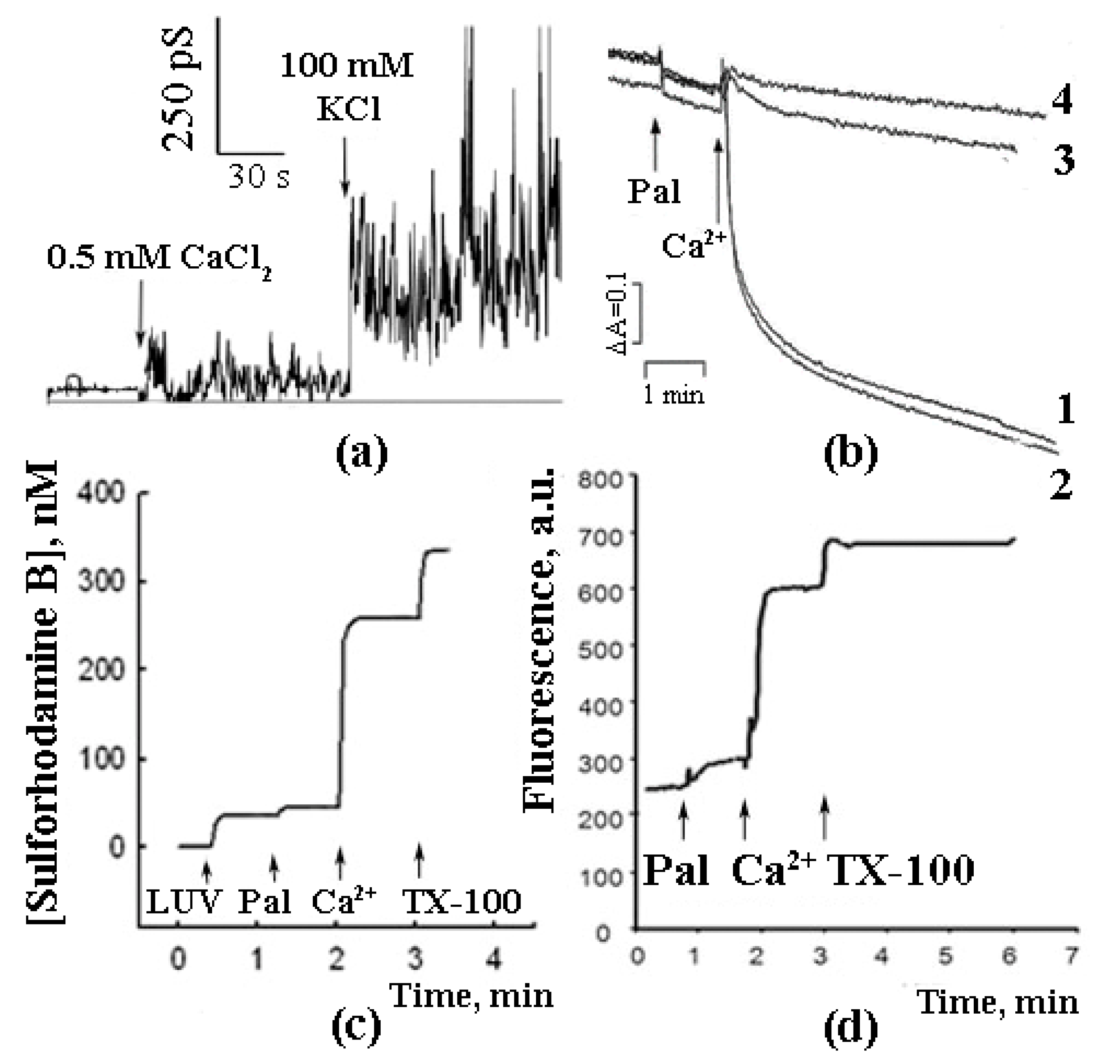

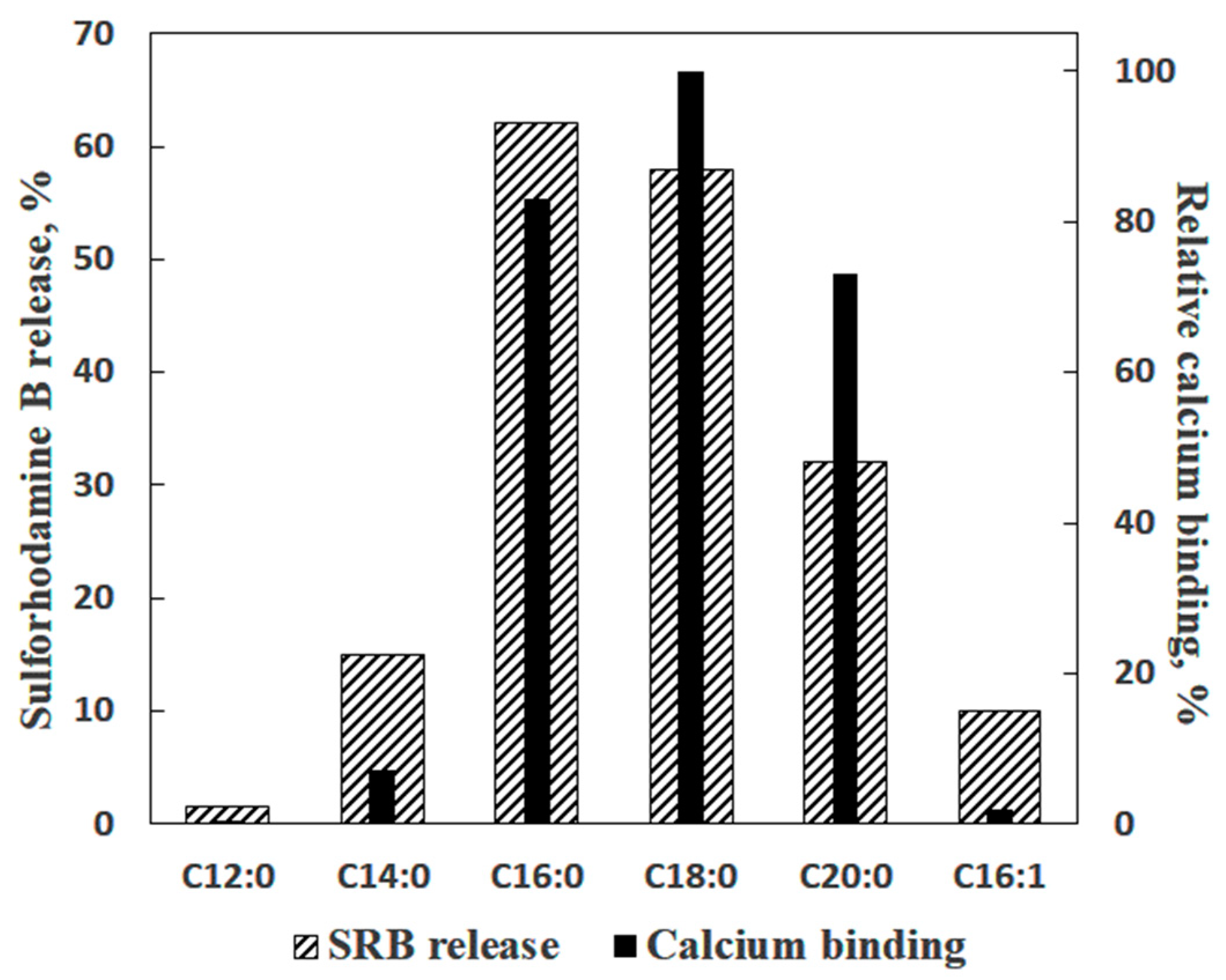

2. Saturated Fatty Acids as Inducers of Membrane Permeabilization

3. Is PA-mPT Based on a General Mechanism of PA/Ca2+-Induced Permeabilization of Lipid Membranes?

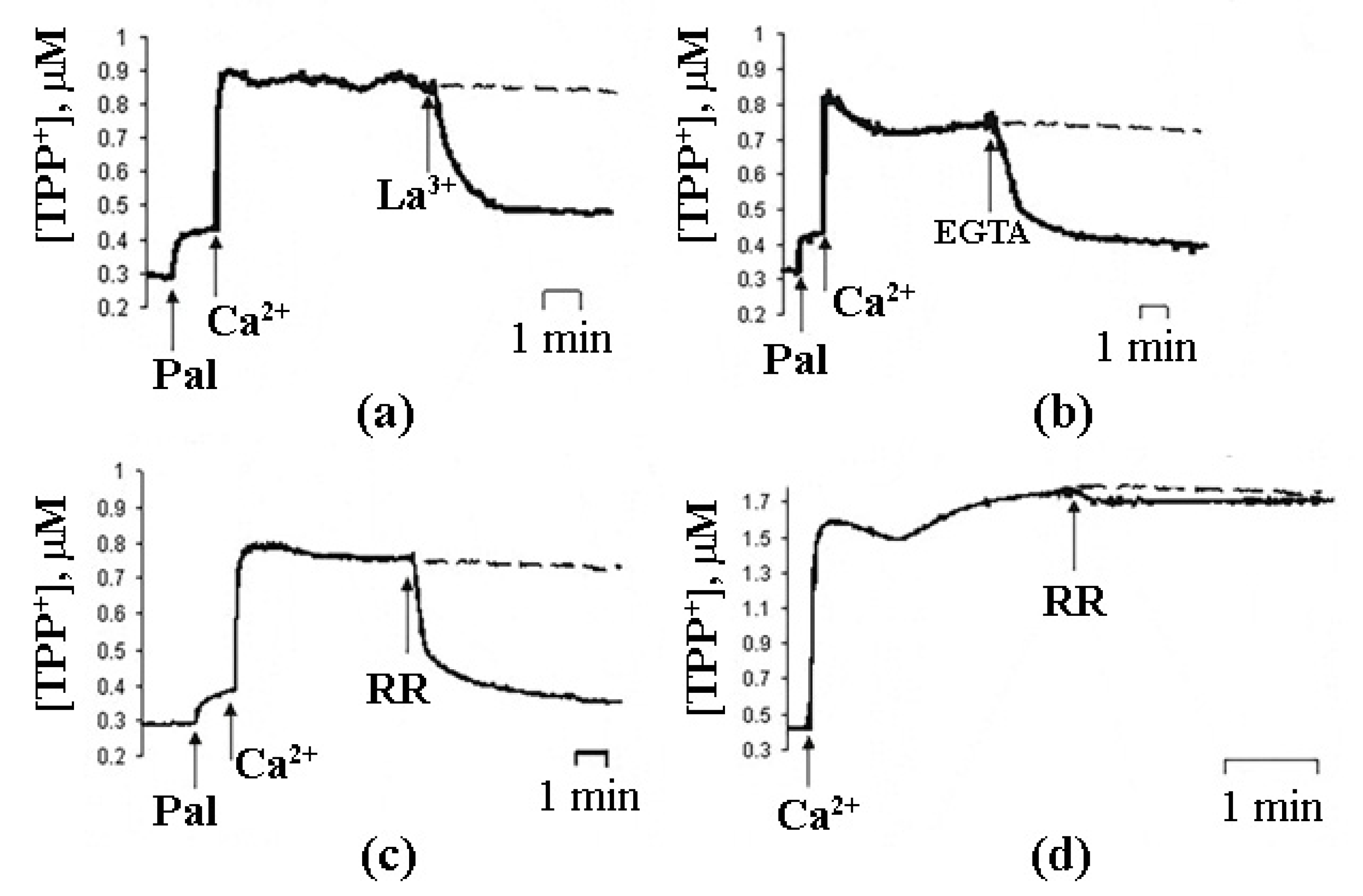

4. Molecular Mechanism of PA-mPT

5. Properties of PA-mPTP and Its Regulation

6. Differences between PA-mPT and Classical mPT

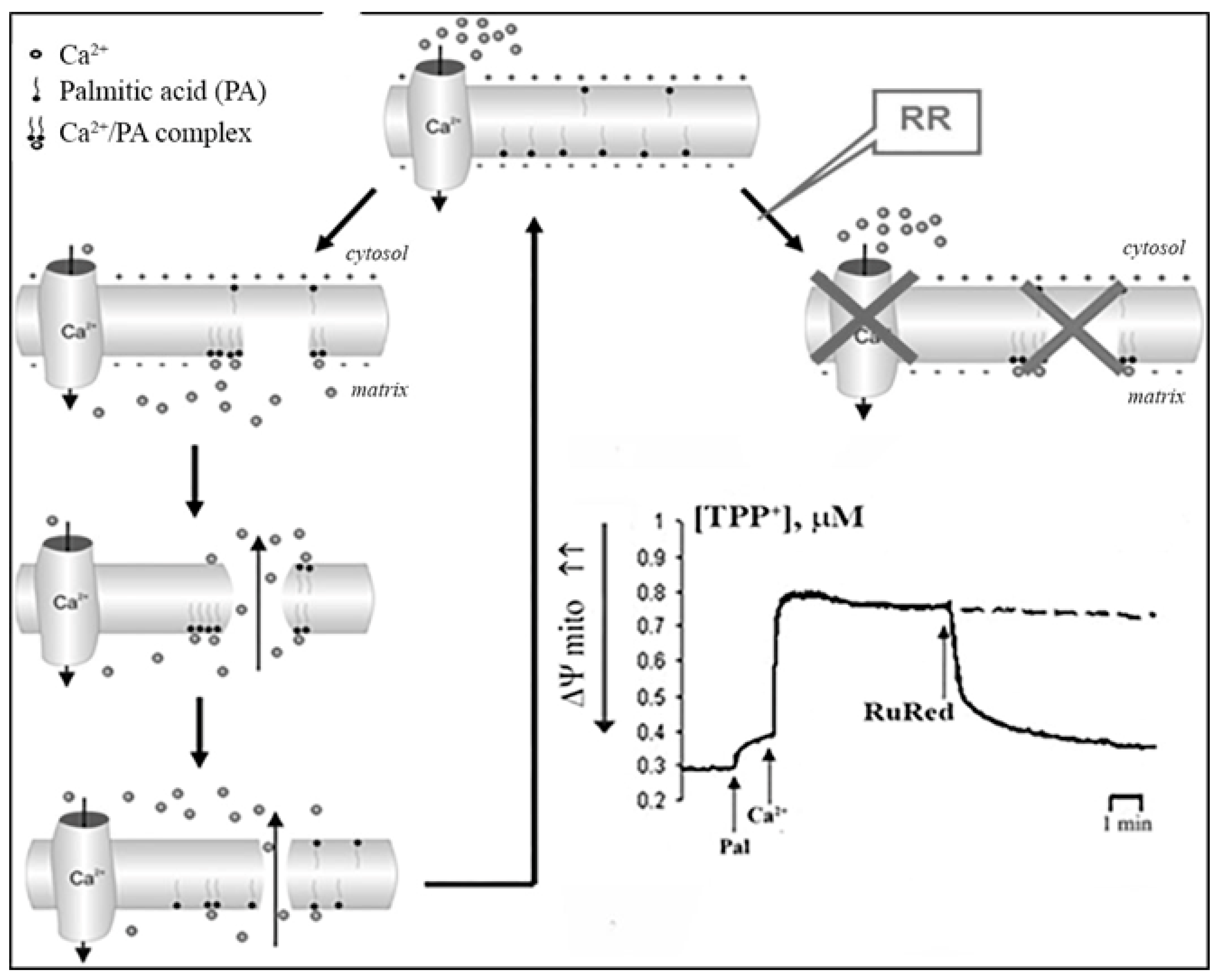

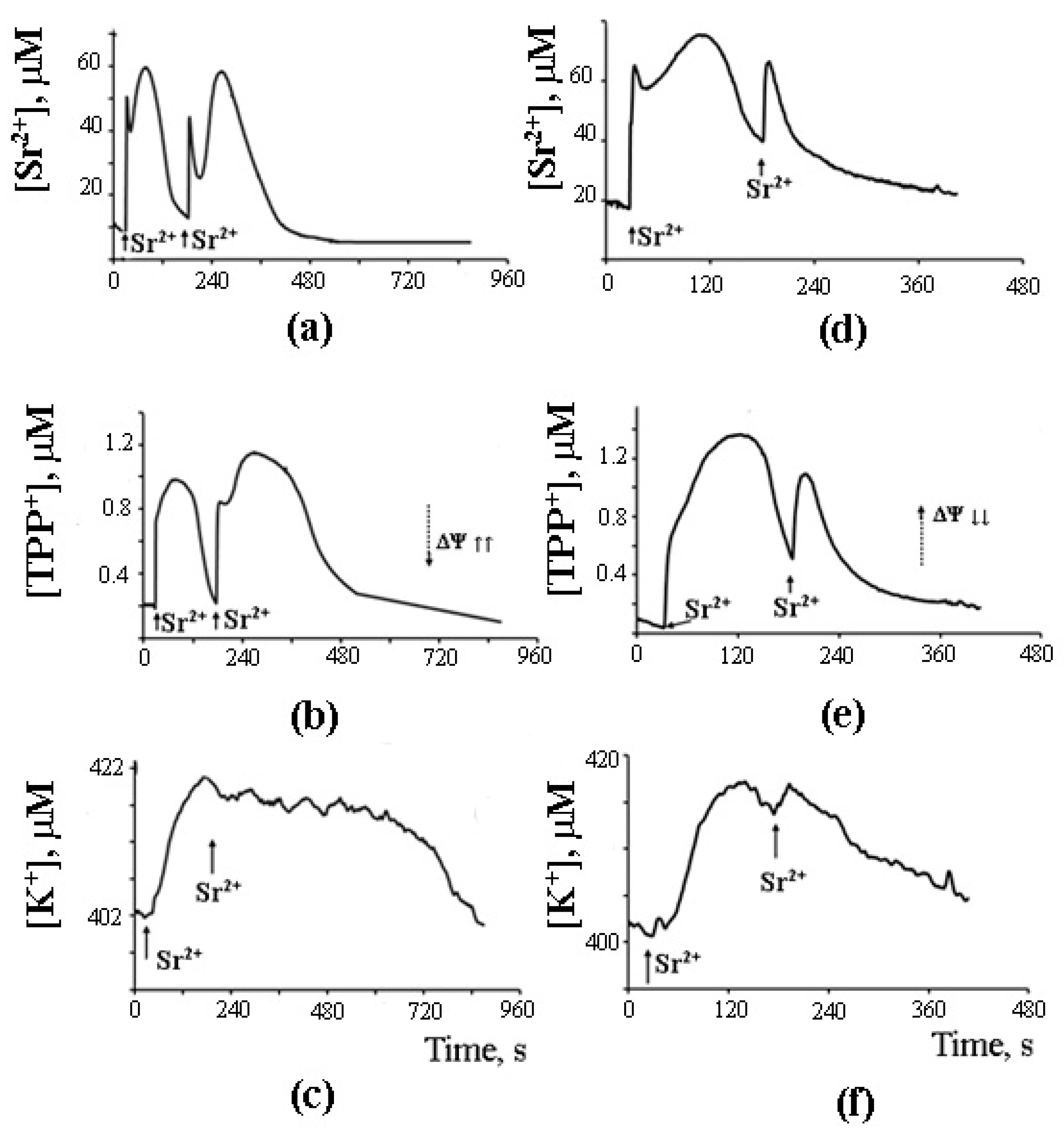

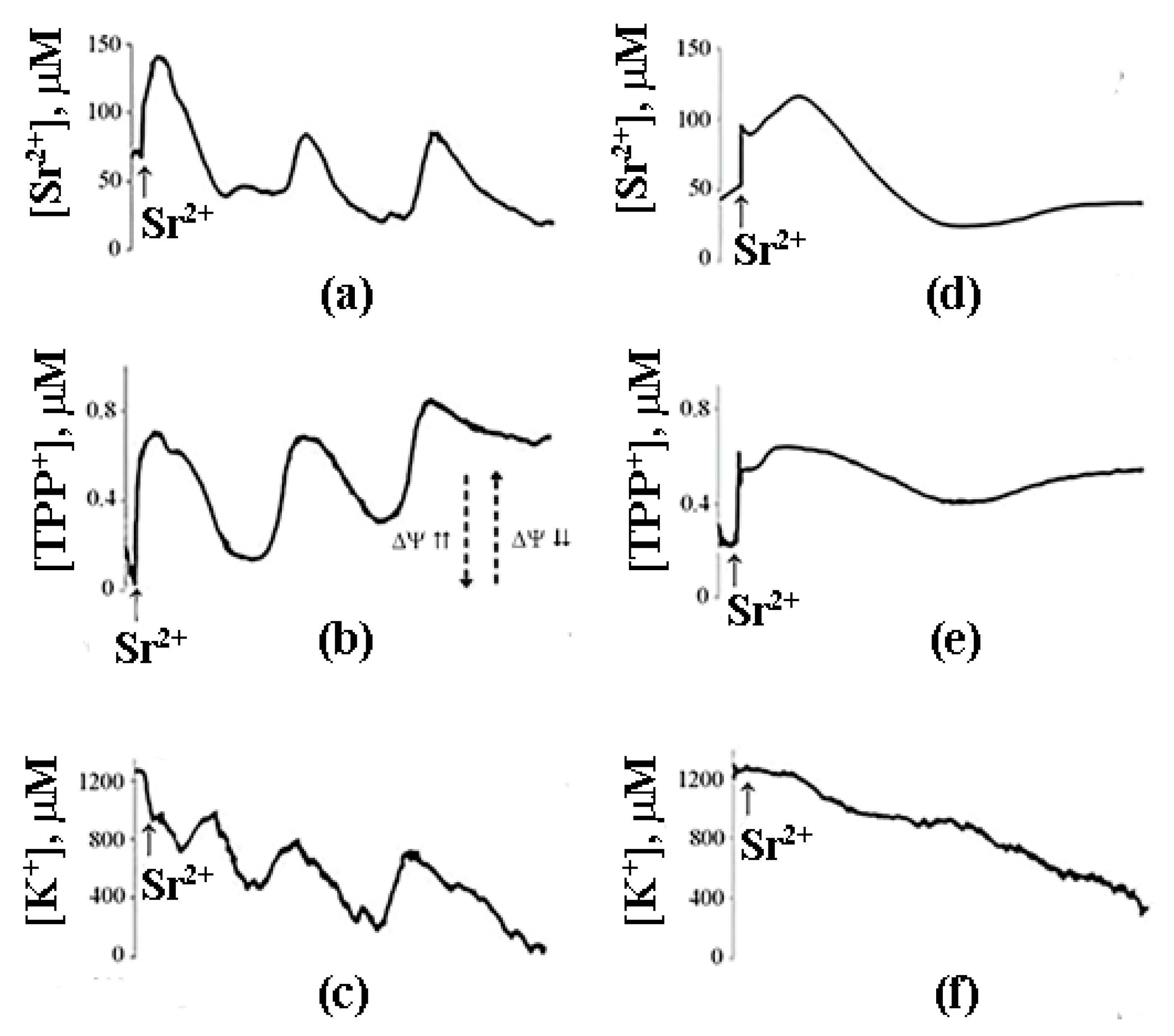

7. The Mechanism of Formation of PA-mPT Pores

8. A Possible Role of PA-mPT in the Emergency Release of Ca2+ from Mitochondria and Maintenance of Ion Homeostasis

9. The Mechanism of PA-mPT-Mediated Protection against Ca2+ Overload and mPTP Activation

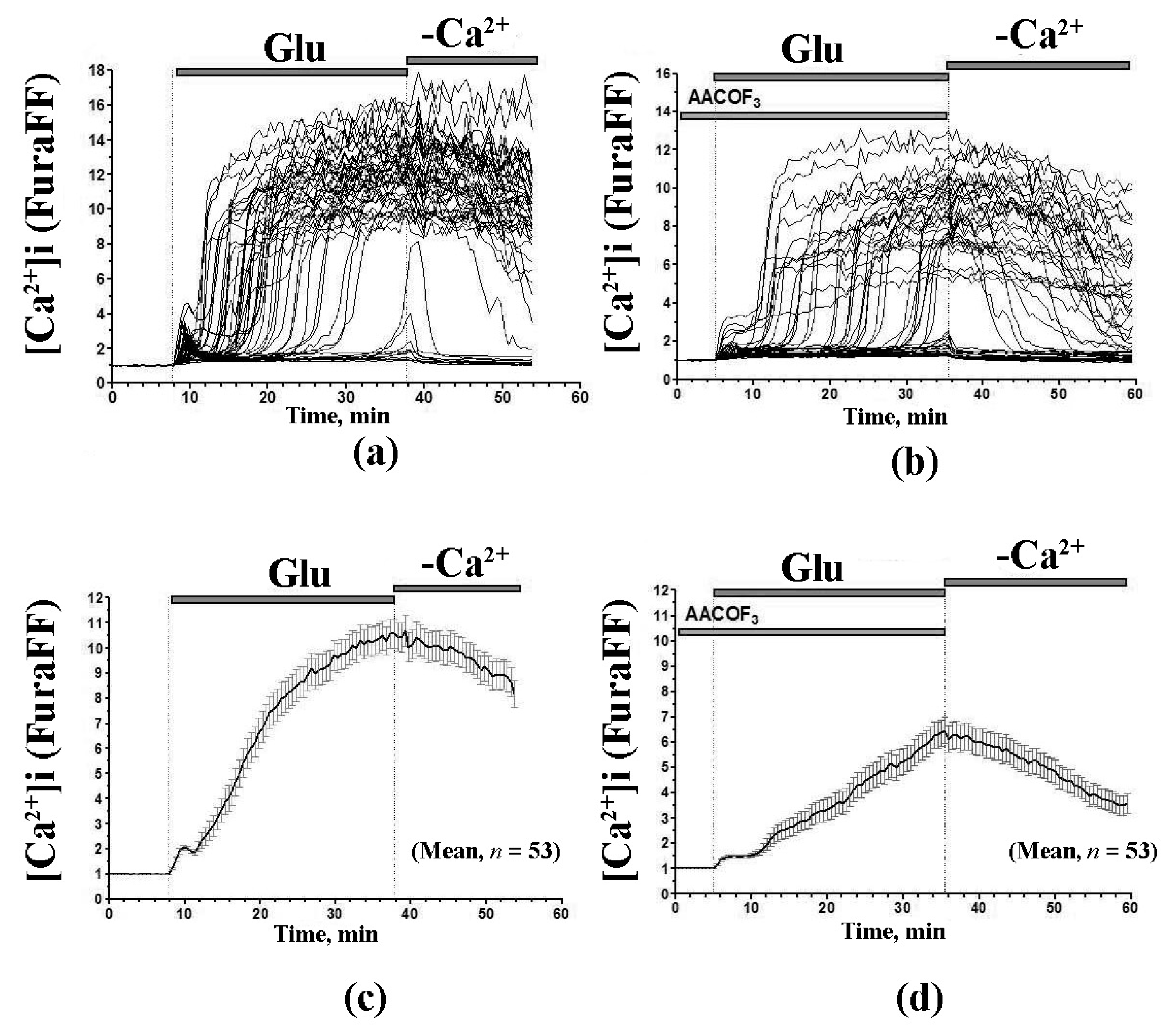

10. A Possible Role of PA-mPT in the Glutamate-Induced Neurotoxicity

11. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carraro, M.; Carrer, A.; Urbani, A.; Bernardi, P. Molecular nature and regulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore(s), drug target(s) in cardioprotection. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 144, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bround, M.J.; Bers, D.M.; Molkentin, J.D. A 20/20 view of ANT function in mitochondrial biology and necrotic cell death. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 144, A3–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnatsakanyan, N.; Jonas, E.A. ATP synthase c-subunit ring as the channel of mitochondrial permeability transition: Regulator of metabolism in development and degeneration. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 144, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petronilli, V.; Miotto, G.; Canton, M.; Brini, M.; Colonna, R.; Bernardi, P.; Di Lisa, F. Transient and long-lasting openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore can be monitored directly in intact cells by changes in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Biophys. J. 1999, 76, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernardi, P.; von Stockum, S. The permeability transition pore as a Ca(2+) release channel: New answers to an old question. Cell Calcium 2012, 52, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mnatsakanyan, N.; Llaguno, M.C.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Weber, J.; Sigworth, F.J.; Jonas, E.A. A mitochondrial megachannel resides in monomeric F1FO ATP synthase. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neginskaya, M.A.; Solesio, M.E.; Berezhnaya, E.V.; Amodeo, G.F.; Mnatsakanyan, N.; Jonas, E.A.; Pavlov, E.V. ATP Synthase C-Subunit-Deficient Mitochondria Have a Small Cyclosporine A-Sensitive Channel, but Lack the Permeability Transition Pore. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urbani, A.; Giorgio, V.; Carrer, A.; Franchin, C.; Arrigoni, G.; Jiko, C.; Abe, K.; Maeda, S.; Shinzawa-Itoh, K.; Bogers, J.F.M.; et al. Purified F-ATP synthase forms a Ca(2+)-dependent high-conductance channel matching the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karch, J.; Bround, M.J.; Khalil, H.; Sargent, M.A.; Latchman, N.; Terada, N.; Peixoto, P.M.; Molkentin, J.D. Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition by deletion of the ANT family and CypD. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, J.E.; Carroll, J.; He, J. Reply to Bernardi: The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and the ATP synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2745–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, P. Mechanisms for Ca(2+)-dependent permeability transition in mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2743–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironova, G.D.; Lazareva, A.; Gateau-Roesch, O.; Tyynela, J.; Pavlov, Y.; Vanier, M.; Saris, N.E. Oscillating Ca2+-induced channel activity obtained in BLM with a mitochondrial membrane component. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1997, 29, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironova, G.D.; Gateau-Roesch, O.; Levrat, C.; Gritsenko, E.; Pavlov, E.; Lazareva, A.V.; Limarenko, E.; Rey, C.; Louisot, P.; Saris, N.E. Palmitic and stearic acids bind Ca2+ with high affinity and form nonspecific channels in black-lipid membranes. Possible relation to Ca2+-activated mitochondrial pores. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2001, 33, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gateau-Roesch, O.; Pavlov, E.; Lazareva, A.V.; Limarenko, E.A.; Levrat, C.; Saris, N.E.; Louisot, P.; Mironova, G.D. Calcium-binding properties of the mitochondrial channel-forming hydrophobic component. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000, 32, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agafonov, A.V.; Gritsenko, E.N.; Shlyapnikova, E.A.; Kharakoz, D.P.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Lezhnev, E.I.; Saris, N.E.; Mironova, G.D. Ca2+-induced phase separation in the membrane of palmitate-containing liposomes and its possible relation to membrane permeabilization. J. Membr. Biol. 2007, 215, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agafonov, A.; Gritsenko, E.; Belosludtsev, K.; Kovalev, A.; Gateau-Roesch, O.; Saris, N.E.; Mironova, G.D. A permeability transition in liposomes induced by the formation of Ca2+/palmitic acid complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1609, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mironova, G.D.; Gritsenko, E.; Gateau-Roesch, O.; Levrat, C.; Agafonov, A.; Belosludtsev, K.; Prigent, A.F.; Muntean, D.; Dubois, M.; Ovize, M. Formation of palmitic acid/Ca2+ complexes in the mitochondrial membrane: A possible role in the cyclosporin-insensitive permeability transition. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2004, 36, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironova, G.D.; Belosludtsev, K.N.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Gritsenko, E.N.; Khodorov, B.I.; Saris, N.E. Mitochondrial Ca2+ cycle mediated by the palmitate-activated cyclosporin A-insensitive pore. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2007, 39, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.; Sokolove, P.M. Palmitic acid opens a novel cyclosporin A-insensitive pore in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 386, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosludtsev, K.N.; Trudovishnikov, A.S.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Agafonov, A.V.; Mironova, G.D. Palmitic acid induces the opening of a Ca2+-dependent pore in the plasma membrane of red blood cells: The possible role of the pore in erythrocyte lysis. J. Membr. Biol. 2010, 237, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosludtsev, K.N.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Mironova, G.D. Possible mechanism for formation and regulation of the palmitate-induced cyclosporin A-insensitive mitochondrial pore. Biochemistry 2005, 70, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belosludtseva, N.V.; Belosludtsev, K.N.; Agafonov, A.V.; Mironova, G.D. [Effect of cholesterol on the formation of palmitate/Ca(2+)-activated pore in mitochondria and liposomes]. Biofizika 2009, 54, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Belosludtsev, K.N.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Mironova, G.D. [The role of a mitochondrial palmitate/Ca(2+)-activated pore in palmitate-induced apoptosis]. Biofizika 2008, 53, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Belosludtsev, K.; Saris, N.E.; Andersson, L.C.; Belosludtseva, N.; Agafonov, A.; Sharma, A.; Moshkov, D.A.; Mironova, G.D. On the mechanism of palmitic acid-induced apoptosis: The role of a pore induced by palmitic acid and Ca2+ in mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2006, 38, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, V.F.; Shevchenko, E.V. Lipid pores and stability of cell membranes. Vestn. Ross. Akad. Med. Nauk. 1995, 10, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Antonov, V.F.; Shevchenko, E.V.; Smirnova, E.; Yakovenko, E.V.; Frolov, A.V. Stable cupola-shaped bilayer lipid membranes with mobile Plateau-Gibbs border: Expansion-shrinkage of membrane due to thermal transitions. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1992, 61, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, R.P. Mechanical Properties of the Red Cell Membrane. Ii. Viscoelastic Breakdown of the Membrane. Biophys. J. 1964, 4, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, G.; Knoll, W. Densitometric Characterization of Aqueous Lipid Dispersions. Ber. Bunsen. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K.; Papahadjopoulos, D. Phase transitions and phase separations in phospholipid membranes induced by changes in temperature, pH, and concentration of bivalent cations. Biochemistry 1975, 14, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidor, I.G.; Chernomordik, L.V.; Sukharev, S.I.; Chizmadzhev, Y.A. The Reversible Electrical Breakdown of Bilayer Lipid-Membranes Modified by Uranyl Ions. Bioelectroch. Bioener. 1982, 9, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, R.; Beckers, F.; Zimmermann, U. Reversible Electrical Breakdown of Lipid Bilayer Membranes—Charge-Pulse Relaxation Study. J. Membr. Biol. 1979, 48, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodrova, M.E.; Dedukhova, V.I.; Samartsev, V.N.; Mokhova, E.N. Role of the ADP/ATP-antiporter in fatty acid-induced uncoupling of Ca2+-loaded rat liver mitochondria. Iubmb. Life 2000, 50, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sultan, A.; Sokolove, P.M. Free fatty acid effects on mitochondrial permeability: An overview. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 386, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzuto, R.; Brini, M.; Murgia, M.; Pozzan, T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science 1993, 262, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saris, N.E. Stimulation of phospholipase A2 activity in mitochondria by magnesium and polyamines. Magnes. Res. 1994, 7, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glover, S.; de Carvalho, M.S.; Bayburt, T.; Jonas, M.; Chi, E.; Leslie, C.C.; Gelb, M.H. Translocation of the 85-kDa phospholipase A2 from cytosol to the nuclear envelope in rat basophilic leukemia cells stimulated with calcium ionophore or IgE/antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 15359–15367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loo, R.W.; Conde-Frieboes, K.; Reynolds, L.J.; Dennis, E.A. Activation, inhibition, and regiospecificity of the lysophospholipase activity of the 85-kDa group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 19214–19219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thorne, T.E.; Voelkel-Johnson, C.; Casey, W.M.; Parks, L.W.; Laster, S.M. The activity of cytosolic phospholipase A2 is required for the lysis of adenovirus-infected cells by tumor necrosis factor. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 8502–8507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venediktova, N.; Shigaeva, M.; Belova, S.; Belosludtsev, K.; Belosludtseva, N.; Gorbacheva, O.; Lezhnev, E.; Lukyanova, L.; Mironova, G. Oxidative phosphorylation and ion transport in the mitochondria of two strains of rats varying in their resistance to stress and hypoxia. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2013, 383, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kim, C.N.; Yang, J.; Jemmerson, R.; Wang, X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: Requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell 1996, 86, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

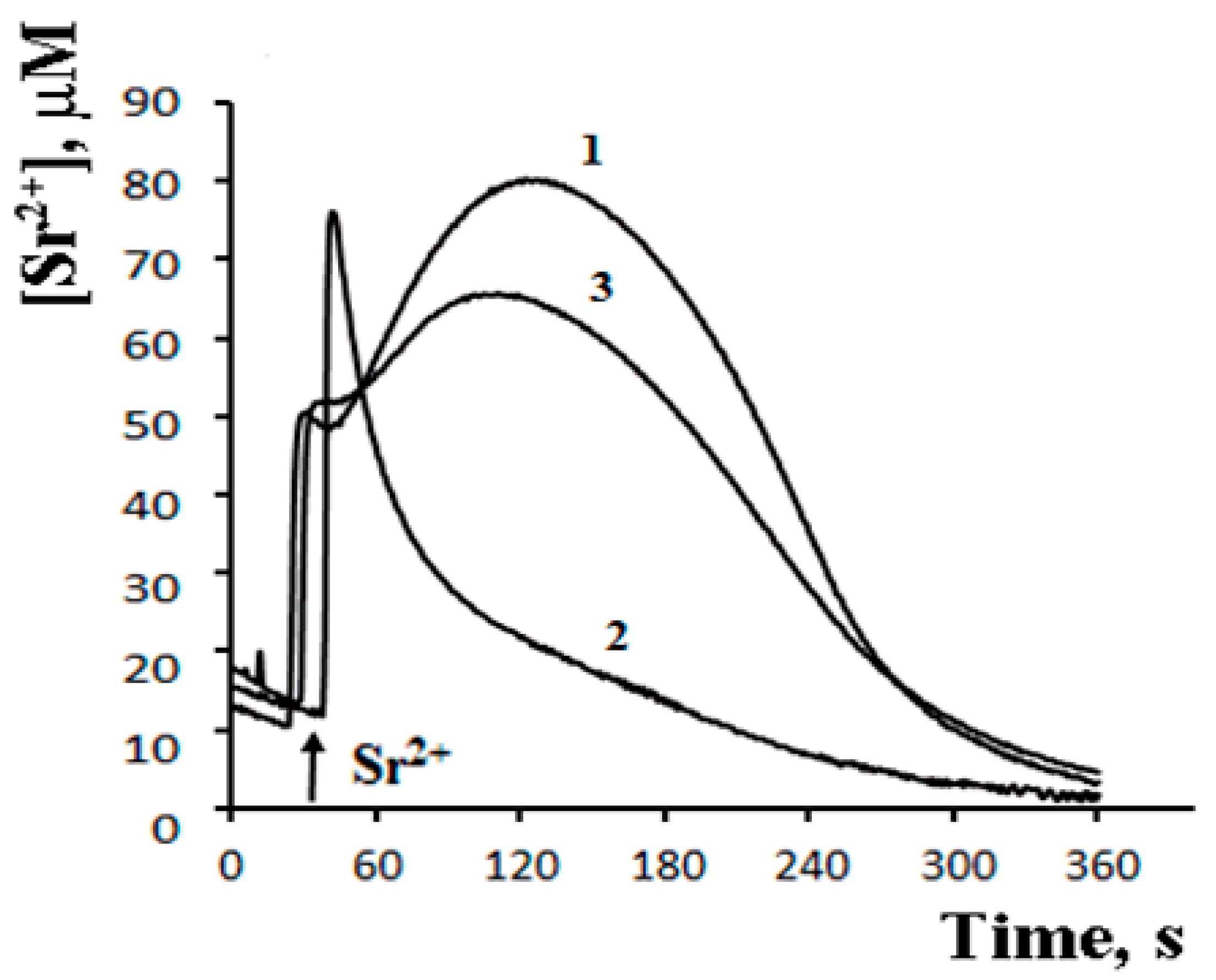

- Gylkhandanyan, A.V.; Evtodienko, Y.V.; Zhabotinsky, A.M.; Kondrashova, M.N. Continuous Sr2+-induced oscillations of the ionic fluxes in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1976, 66, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ichas, F.; Jouaville, L.S.; Sidash, S.S.; Mazat, J.P.; Holmuhamedov, E.L. Mitochondrial calcium spiking: A transduction mechanism based on calcium-induced permeability transition involved in cell calcium signalling. FEBS Lett. 1994, 348, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmuhamedov, E.L.; Teplova, V.V.; Chukhlova, E.A.; Evtodienko, Y.V.; Ulrich, R.G. Strontium excitability of the inner mitochondrial membrane: Regenerative strontium-induced strontium release. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1995, 36, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mironova, G.D.; Saris, N.E.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Agafonov, A.V.; Elantsev, A.B.; Belosludtsev, K.N. Involvement of palmitate/Ca2+(Sr2+)-induced pore in the cycling of ions across the mitochondrial membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeiffer, D.R.; Schmid, P.C.; Beatrice, M.C.; Schmid, H.H. Intramitochondrial phospholipase activity and the effects of Ca2+ plus N-ethylmaleimide on mitochondrial function. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254, 11485–11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, B.I.; Severina, E.P.; Gogvadze, V.G.; Chukhlova, E.A.; Evtodienko Yu, V. Participation of endogenous fatty acids in Ca2+ release activation from mitochondria. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 1985, 4, 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- De Villiers, M.; Lochner, A. Mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes: Role of free fatty acids, acyl-CoA and acylcarnitine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1986, 876, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E.J.; Cooper, M.B. Calcium and magnesium ion losses in response to stimulants of efflux applied to heart, liver and kidney mitochondria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1981, 103, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosludtsev, K.N.; Saris, N.E.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Trudovishnikov, A.S.; Lukyanova, L.D.; Mironova, G.D. Physiological aspects of the mitochondrial cyclosporin A-insensitive palmitate/Ca2+-induced pore: Tissue specificity, age profile and dependence on the animal’s adaptation to hypoxia. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2009, 41, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova, G.D.; Shigaeva, M.I.; Gritsenko, E.N.; Murzaeva, S.V.; Gorbacheva, O.S.; Germanova, E.L.; Lukyanova, L.D. Functioning of the mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channel in rats varying in their resistance to hypoxia. Involvement of the channel in the process of animal’s adaptation to hypoxia. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2010, 42, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, P.; Petronilli, V. The permeability transition pore as a mitochondrial calcium release channel: A critical appraisal. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1996, 28, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severina, E.P.; Evtodienko Iu, V. [Phospholipase A2 localization in mitochondria]. Biokhimiia 1981, 46, 1199–1201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murakami, M.; Taketomi, Y.; Miki, Y.; Sato, H.; Hirabayashi, T.; Yamamoto, K. Recent progress in phospholipase A(2) research: From cells to animals to humans. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011, 50, 152–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pshennikova, M.G.; Belkina, L.M.; Bakhtina, L.Y.; Baida, L.A.; Smirin, B.V.; Malyshev, I.Y. HSP70 stress proteins, nitric oxide, and resistance of August and Wistar rats to myocardial infarction. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2001, 132, 741–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadd, M.E.; Broekemeier, K.M.; Crouser, E.D.; Kumar, J.; Graff, G.; Pfeiffer, D.R. Mitochondrial iPLA2 activity modulates the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and influences the permeability transition. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 6931–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khodorov, B. Glutamate-induced deregulation of calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction in mammalian central neurones. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2004, 86, 279–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budd, S.L.; Nicholls, D.G. Mitochondria, calcium regulation, and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 2282–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolshakov, A.P.; Mikhailova, M.M.; Szabadkai, G.; Pinelis, V.G.; Brustovetsky, N.; Rizzuto, R.; Khodorov, B.I. Measurements of mitochondrial pH in cultured cortical neurons clarify contribution of mitochondrial pore to the mechanism of glutamate-induced delayed Ca2+ deregulation. Cell Calcium 2008, 43, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova, G.D.; Belosludtsev, K.N.; Surin, A.M.; Trudovishnikov, A.S.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Pinelis, V.G.; Krasilnikova, I.A.; Khodorov, B.I. Mitochondrial Lipid Pore in the Mechanism of Glutamate-Induced Calcium Deregulation of Brain Neurons. Biochem. Mosc. Suppl. S 2012, 6, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, M. Mitochondrial intermembrane junctional complexes and their role in cell death. J. Physiol. 2000, 529 Pt 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparagna, G.C.; Hickson-Bick, D.L.; Buja, L.M.; McMillin, J.B. A metabolic role for mitochondria in palmitate-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 279, H2124–H2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lipids | Relative Ca2+ Binding |

|---|---|

| Lauric acid (12:0) | 0.50 ± 0.03 |

| Myristic acid (14:0) | 7.30 ± 0.25 |

| Palmitic acid (16:0) | 83.00 ± 0.75 |

| Stearic acid (18:0) | 100.00 |

| Eicosanoic acid (20:0) | 73.00 ± 2.5 |

| Docosanoic acid (22:0) | 44.00 ± 1.2 |

| Lignoceric acid (24:0) | 15.00 ± 0.35 |

| Palmitoleic acid (16:1) | 1.90 ± 0.08 |

| Oleic acid | 5.70 ± 0.12 |

| Linoleic acid (18:2) | 0.65 ± 0.04 |

| Linoleinic acid (18:3) | 0.87 ± 0.05 |

| Arachidonic acid (20:4) | 1.10 ± 0.05 |

| 1-Palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine | 0.43 ± 0.02 |

| 1-Stearoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine | 0.47 ± 0.02 |

| 1-Lauroyl-lysophosphatidylcholine | 0.43 ± 0.01 |

| Lysophosphatidylserine | 0.54 ± 0.03 |

| 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine | 0.40 ± 0.2 |

| 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine | 0.22 ± 0.01 |

| 1-Palmitoyl-sn-glycero-1-3-phosphatidylethanolamine | 0.76 ± 0.03 |

| Palmitoil-CoA | 0.43 ± 0.02 |

| Cardiolipin | 0.60 ± 0.03 |

| L-α-phosphatidic acid | 19.50 ± 0.8 |

| Cholesterol | 0.33 ± 0.01 |

| Cerebrosides | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Sphingomyelin | 0.30 ± 0.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mironova, G.D.; Pavlov, E.V. Mitochondrial Cyclosporine A-Independent Palmitate/Ca2+-Induced Permeability Transition Pore (PA-mPT Pore) and Its Role in Mitochondrial Function and Protection against Calcium Overload and Glutamate Toxicity. Cells 2021, 10, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010125

Mironova GD, Pavlov EV. Mitochondrial Cyclosporine A-Independent Palmitate/Ca2+-Induced Permeability Transition Pore (PA-mPT Pore) and Its Role in Mitochondrial Function and Protection against Calcium Overload and Glutamate Toxicity. Cells. 2021; 10(1):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010125

Chicago/Turabian StyleMironova, Galina D., and Evgeny V. Pavlov. 2021. "Mitochondrial Cyclosporine A-Independent Palmitate/Ca2+-Induced Permeability Transition Pore (PA-mPT Pore) and Its Role in Mitochondrial Function and Protection against Calcium Overload and Glutamate Toxicity" Cells 10, no. 1: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010125

APA StyleMironova, G. D., & Pavlov, E. V. (2021). Mitochondrial Cyclosporine A-Independent Palmitate/Ca2+-Induced Permeability Transition Pore (PA-mPT Pore) and Its Role in Mitochondrial Function and Protection against Calcium Overload and Glutamate Toxicity. Cells, 10(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010125