The Potential Role of Cobalt and/or Organic Fertilizers in Improving the Growth, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Moringa oleifera

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Procedures

2.2. Application of Organic Fertilizers

2.3. Soil Analysis

2.4. Measurement of Plant Growth Characteristics

2.5. Analysis of the Nutritional Composition of the Plant

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth and Yield of Moringa Plants

3.2. Mineral Elements of Moringa Leaves

3.3. Nutritional Composition of Moringa Leaves

3.4. Correlation Matrix

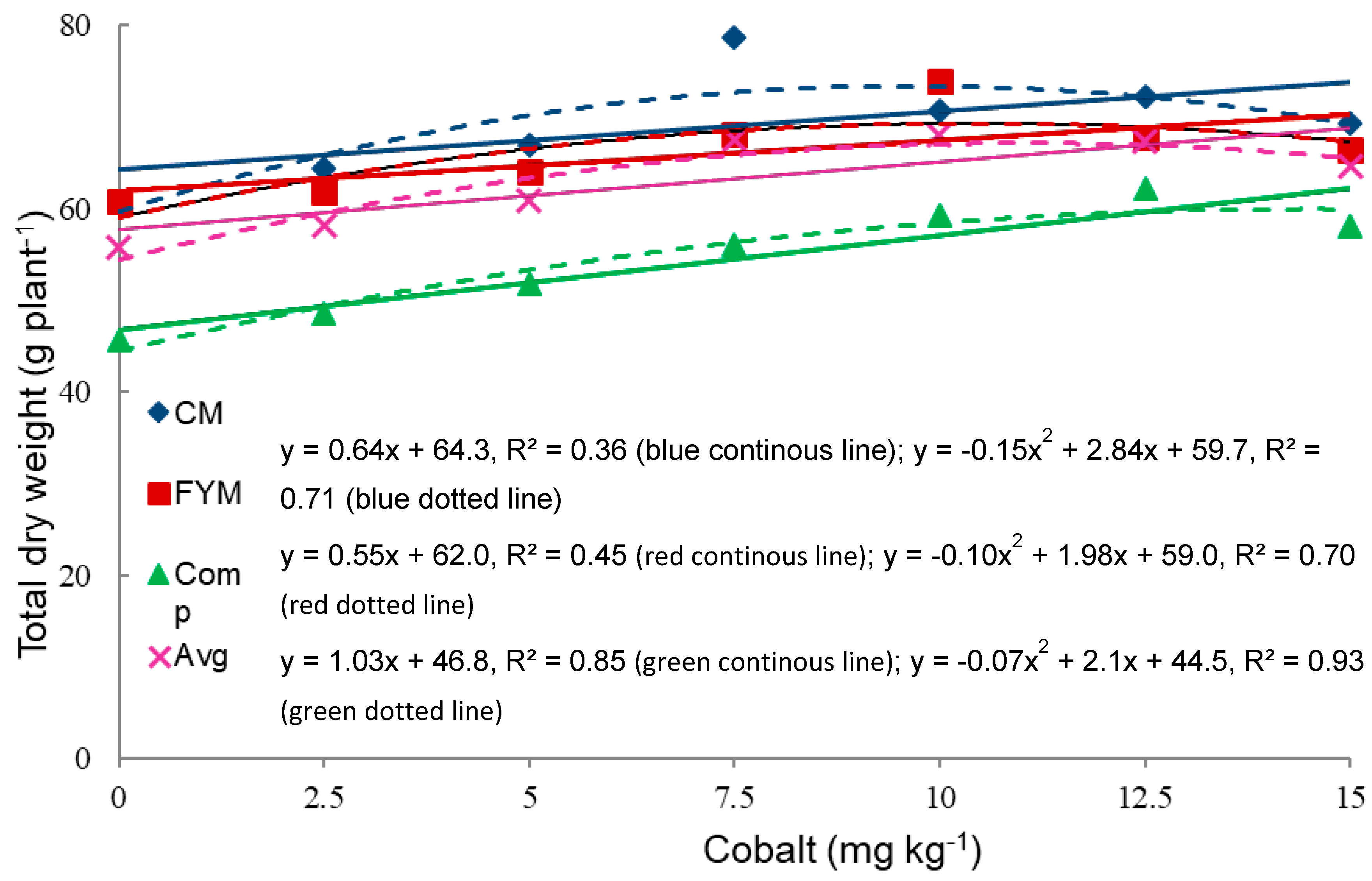

3.5. Linear and Quadratic Response of the Total Dry Weight (TDW) to Cobalt Level

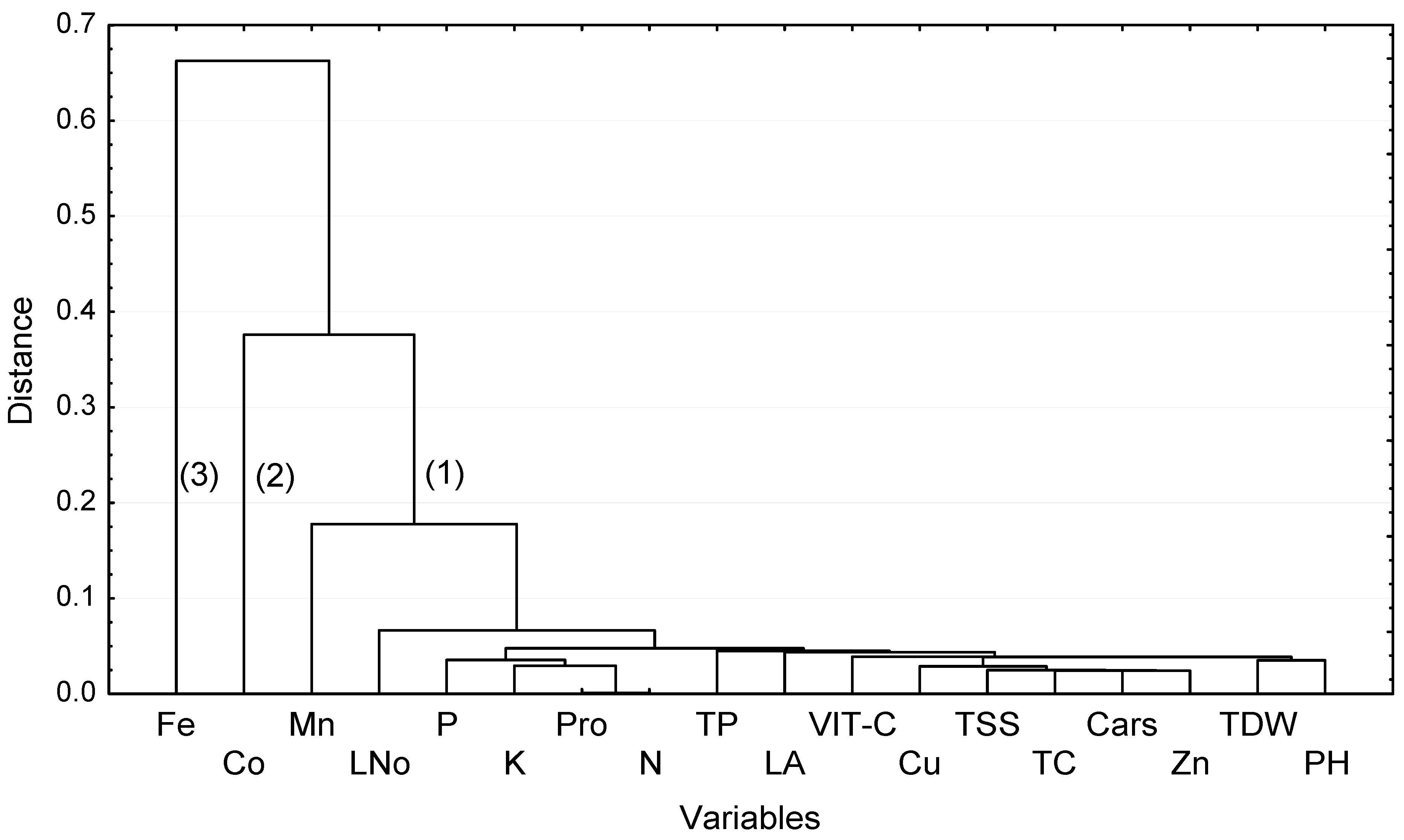

3.6. Cluster Analysis

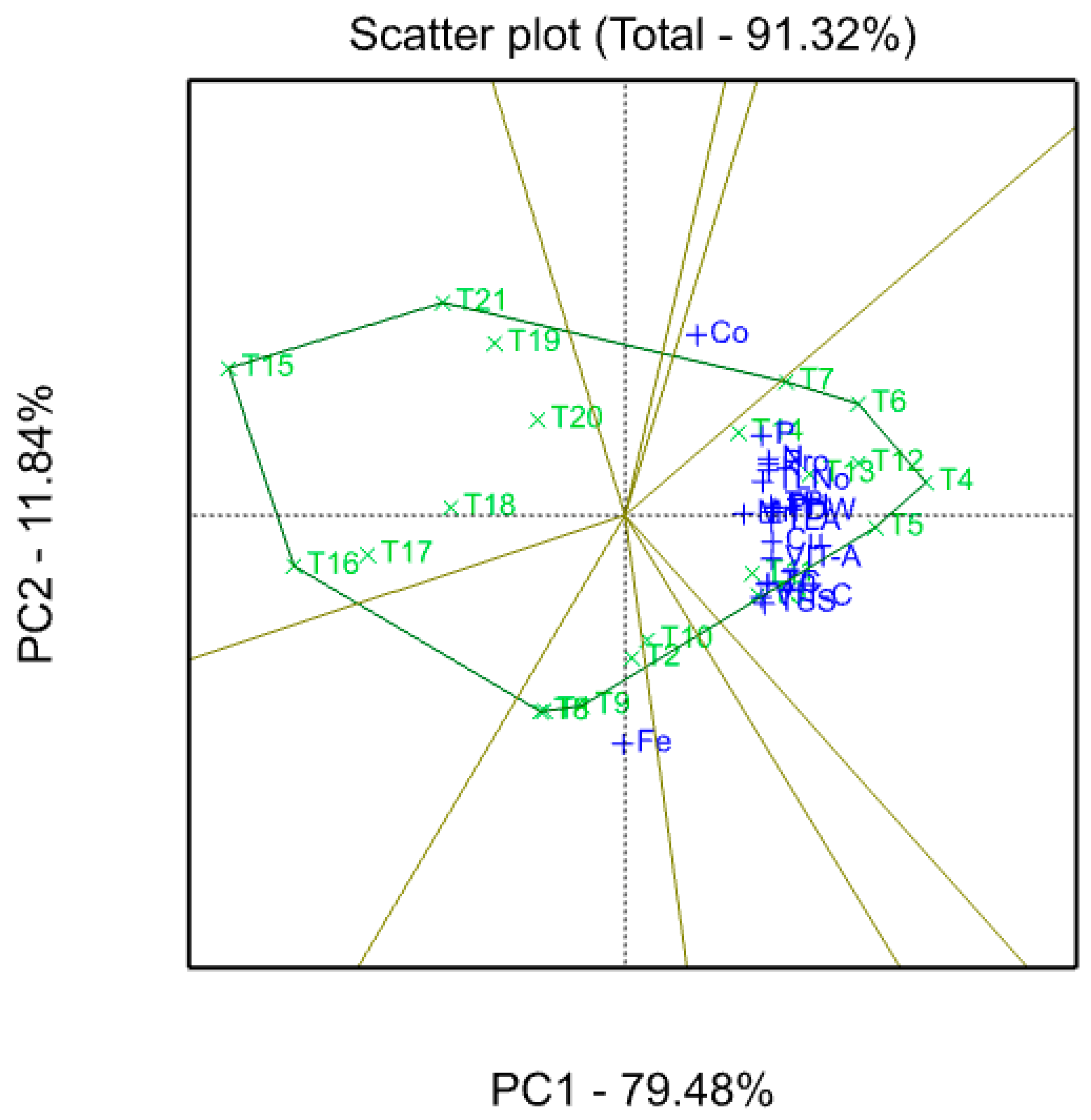

3.7. Biplot Graph

3.8. Trait Relations (Vector Graph)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jahn, S.A.A. Using moringa seeds as coagulants in developing countries. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 1988, 80, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Latif, S.; Ashraf, M.; Gilani, A.H. Moringa oleifera: A food plant with multiple medicinal uses. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.N.; Mellon, F.A.; Foidl, N.; Pratt, J.H.; Dupont, M.S.; Perkins, L.; Kroon, P.A. Profiling glucosinolates and phenolics in vegetative and reproductive tissues of the multi-purpose trees Moringa oleifera L. (Horseradish tree) and Moringa stenopetala L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3546–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; Khan, M.T.; Ather, A.; Wilke, D.V.; Jimenez, P.C.; Pessoa, C.; de Moraes, M.E.; de Moraes, M.O. Studies of the anticancer potential of plants used in Bangladeshi folk medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 99, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emongor, V.E. Moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.): A Review. Acta Hortic. 2011, 911, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M. Agroecology: A new research and development paradigm for world agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1989, 27, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, M.; Horiuchi, T.; Oba, S. Evaluation of the SPAD values in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) leaves in relation to different fertilizer applications. Plant Prod. Sci. 2003, 6, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, M.T.; Selim, E.M.; EL-Ghamry, A.M. Integrated effects of bio and mineral fertilizers and humic substances on growth, yield and nutrient contents of fertigated cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) grown on sandy soils. J. Agron. 2011, 10, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, M.M.; Semida, W.M.; Hemida, K.A.; Abdelhamid, M.T. The effect of compost on growth and yield of Phaseolus vulgaris plants grown under saline soil. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2016, 5, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, M.M.; Mounzer, O.H.; Alarcón, J.J.; Abdelhamid, M.T.; Howladar, S.M. Growth, heavy metal status and yield of salt-stressed wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants as affected by the integrated application of bio-, organic and inorganic nitrogen-fertilizers. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2016, 89, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, J.F.; Hornick, S.B.; Youngberg, I.G. Alternative agriculture in the United States: Recent developments and perspectives. In Proceedings of the 8th IFOAM conference on Socio-economics of Organic Agriculture, Budapest, Hungary, 27–30 August 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid, M.; Horiuchi, T.; Oba, S. Composting of rice straw with oilseed rape cake and poultry manure and its effects on faba bean (Vicia faba L.) growth and soil properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 93, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou El-Seoud, M.A.A.; Abd El-Sabour, M.F.; Omer, E.A. Productivity of roselle (Hibiscus Sabdariffa L.) plant as affected by organic waste composts addition to sandy soil. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 1997, 22, 617–624. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid, M.; Horiuchi, T.; Oba, S. Nitrogen uptake by faba bean from 15N-labelled oilseed rape residue and chicken manure with ryegrass as a reference crop. Plant Prod. Sci. 2004, 7, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubuaku, U.M.; Ede, A.E.; Baiyeri, K.P.; Ezeaku, P.I. Application of poultry manure and its effect on growth and performance of potted moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam) plants raised for urban dwellers’ use. Am. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. Tech. 2015, 5, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowicki, B. The influence of cobalt fertilization on quantity and quality of hay from dried meadow using various NPK doses. Ann. UMCS Sect. E Agric. 2003, 54, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fageria, N.K.; Moraes, M.F.; Ferreira, E.P.B.; Knupp, A.M. Biofortification of trace elements in food crops for human health. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2012, 43, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Mustafa, A.R.A.; El-Sheikh, A.A. Geochemistry and spatial distribution of selected heavy metals in surface soil of Sohag, Egypt: A multivariate statistical and GIS approach. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Chakrabarti, K.; Chakraborty, A. Cobalt and nickel uptake by rice and accumulation in soil amended with municipal solid waste compost. Ecotoxcol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 69, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibak, A. Uptake of cobalt and manganese by winter wheat from a sandy loam soil with and without added farmyard manure and fertilizer nitrogen. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1994, 25, 2675–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, L.M.; Gad, N. Effect of cobalt fertilization on the yield, quality the essential oil composition of parsley leaves. Arab Univ. J. Agric. Sci. Ain Shams Univ. Cairo 2002, 10, 779–802. [Google Scholar]

- Gad, N.; Abd El-Moez, M.R.; El-Sherif, M.H. Physiological effect of cobalt on olive yield and frut quality under rass seder conditions. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2006, 51, 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, L.C.; Searle, P.L.; Daly, B.K. Methods of Chemical Analysis of Soils; New Zealand Soil Bureau: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Black, C.A.; Evans, D.D.; Ensminger, L.; White, G.L.; Clarck, F.E. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2; Agron. Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Cottenie, A.; Verloo, M.; Kiekens, L.; Velghe, G.; Camerlynck, R. Chemical Analysis of Plant and Soil Laboratory of Analytical and Agrochemistry; State University Ghent: Ghent, Belgium, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- King, E.J. Micro Analysis in Medical Biochemistry, 2nd ed.; J. & A. Churchill Ltd.: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.; Cole, C.; Watanabe, F.; Dean, L. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; USDA Circular Nr 939; US Gov. Print. Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1954.

- Chapman, H.D.; Pratt, P.F. Methods of Analysis for Soils, Plants and Water; Univ. California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemm, E.W.; Willis, A.J. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochem. J. 1954, 57, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadzie, B.K.; Orchard, J.E. Routine Post Harvest Screening of Banana/Plantain Hybrids: Criteria and Methods; INIBAP Technical Guidelines 2; International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy; International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain: Montpellier, France; ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Snell, F.D.; Snell, C.T. Colorimetric Methods of Analysis Including Some Turbidimeteric and Nephelometeric Methods; D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1953; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, H.D.; George, C.M. Peach seed dormancy in relation to indigenous inhibitors and applied growth substances. J Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1972, 97, 651–654. [Google Scholar]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzyme in isolated chloroplast: Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In Methods in Enzimology; Packer, L., Douce, R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1987; Volume 148, pp. 350–381. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.P.; Choudhuri, M.A. Implications of water stress-induced changes in the levels of endogenous ascorbic acid and hydrogen peroxide in Vigna seedlings. Physiol. Plant 1983, 58, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. Analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, H. Robust tests for equality of variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling; Olkin, I., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1984; p. 704. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.J.H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, N.; Hassan, N. Response of growth and yield of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) to cobalt nutrition. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 2, 760–765. [Google Scholar]

- Nanwai, R.K.; Sharma, B.D.; Taneja, K.D. Role of organic and inorganic fertilizers for maximizing wheat (Triticum aestivum) yield in sandy loam soils. Crop Res. 1998, 16, 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Moez, M.R.; Gad, N. Effect of organic cotton compost and cobalt application on cowpea plants growth and mineral composition. Egypt J. Appl. Sci. 2002, 17, 426–440. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, E.E.; Gad, N.; Khaled, S.M. Effect of cobalt on growth and chemical composition of peppermint plant grown in newly reclaimed soil. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 628–633. [Google Scholar]

- Gad, N. Productivity of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) plant as affected by cobalt and organic fertilizers. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2011, 7, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, R.; Dube, B.K.; Sinha, P.; Chatterjee, C. Cobalt toxicity effects on growth and metabolism of tomato. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2003, 34, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaylock, A.D.; Davis, T.D.; Jolley, V.D.; Valser, R.H. Influence of cobalt and iron on photosynthesis, chlorophyll, and nutrient content in regreening chlorotic tomatoes and soybeans. J. Plant Nutr. 1986, 9, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; McLaren, R.G.; Metherell, A.K. Fractionation of cobalt and manganese in New Zealand soils. Aust. J. Soil Res. 2001, 39, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; McLaren, R.G.; Metherell, A.K. The availability of native and applied soil cobalt to ryegrass in relation to soil cobalt and manganese status and other soil properties. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2004, 47, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, L.O.; Harbak, H.; Bennekou, P. Cobalt metabolism and toxicology—A brief update. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 432, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, N.; Aziz, E.E.; Kandil, H. Effect of cobalt on growth, herb yield and essential quantity and quality in dill (Anethum graveolens). Middle East J. Agric. Res. 2014, 3, 536–542. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Kang, M.S. GGE Biplot Analysis: A Graphical Tool for Breeders, Geneticists, and Agronomists, 1st ed.; CRD Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Tinker, N.A. An integrated system of biplot analysis for displaying, interpreting, and exploring genotype–by-environment interactions. Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physical properties | Value | |

| Particle size distribution (%) | Coarse sand | 47.78 |

| Fine sand | 40.08 | |

| Silt | 9.14 | |

| Clay | 3.00 | |

| Soil texture | Fine sand | |

| Saturation (%) | 32.1 | |

| Field capacity (%) | 19.2 | |

| Wilting point (%) | 6.1 | |

| Available moisture (%) | 13.1 | |

| Chemical properties | Value | |

| Calcium carbonate (%) | 4.68 | |

| pH (Soil paste) | 8.9 | |

| EC dS m−1 (1:2.5) | 0.44 | |

| Soluble cations (meq L−1) | Ca2+ | 1.97 |

| Mg2+ | 0.86 | |

| Na+ | 1.13 | |

| K+ | 0.42 | |

| Soluble anions (meq L−1) | CO32− | - |

| HCO3− | 0.10 | |

| Cl− | 2.33 | |

| SO42− | 1.95 | |

| Available nutrients (mg kg−1) | N | 22.2 |

| P | 8.0 | |

| K | 72.0 | |

| Fe | 4.5 | |

| Mn | 2.7 | |

| Zn | 4.5 | |

| Cu | 5.2 | |

| Cobalt (mg kg−1) | Soluble Co | 0.35 |

| Available Co | 4.88 | |

| Total Co | 9.88 | |

| Parameter | CM | FYM | Comp |

|---|---|---|---|

| OM (%) | 36.0 | 32.2 | 24.6 |

| EC (dS m−1) | 8.85 | 8.53 | 8.78 |

| pH (1:25) | 6.40 | 6.23 | 8.50 |

| C:N ratio | 7.07 | 6.66 | 8.19 |

| Organic N (kg t−1) | 20.3 | 19.3 | 9.5 |

| Total N (kg t−1) | 29.6 | 28.1 | 13.9 |

| NH4-N (kg t−1) | 9.3 | 8.8 | 4.4 |

| Retained NH4-N (kg t−1) | 4.7 | 4.4 | 2.2 |

| Total P (kg t−1) | 7.8 | 6.5 | 5.7 |

| Total K (kg t−1) | 9.3 | 8.6 | 7.1 |

| Crop available nutrients in first year (kg t−1) | |||

| Available organic N | 7.5 | 7.1 | 3.5 |

| Estimated crop available N | 12.2 | 11.5 | 5.7 |

| Estimated crop available P2O5 | 17.1 | 14.3 | 12.5 |

| Estimated crop available K2O | 10.0 | 9.3 | 7.7 |

| DTPA-extractable (mg kg−1): | |||

| Fe | 5.7 | 515 | 479 |

| Mn | 36.2 | 31.9 | 26.0 |

| Zn | 28.0 | 24.9 | 19.8 |

| Cu | 34.5 | 31.1 | 25.0 |

| Organic Amendment | Cobalt (mg kg−1) | Plant Height (cm) | Leaf Number per Plant | Leaf Area per Plant (cm2) | Dry Weight (g per Plant) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 DAS | 105 DAS | 150 DAS | TDW | |||||

| CM | 0 | 74.8 ± 0.44 * h–j | 24.8 ± 0.14e–g | 1037 ± 6.1d–f | 19.4 ± 0.11j | 20.2 ± 0.12h–j | 21.3 ± 0.12e–i | 60.9 ± 0.36h–j |

| 2.5 | 77.9 ± 0.45gh | 27.7 ± 0.16c–e | 1103 ± 6.4c–e | 21.1 ± 0.12f–h | 21.5 ± 0.13e–h | 21.9 ± 0.13d–f | 64.5 ± 0.38e–h | |

| 5 | 80.4f ± 0.47g | 31.7 ± 0.19ab | 1215 ± 7.1b | 21.8 ± 0.13e–g | 22.5 ± 0.13c–f | 22.8 ± 0.13c–e | 67.0 ± 0.39d–f | |

| 7.5 | 94.1 ± 0.55a | 34.7 ± 0.20a | 1334 ± 7.8a | 24.2 ± 0.14a | 26.5 ± 0.16a | 28.0 ± 0.16a | 78.7 ± 0.46a | |

| 10 | 87.5 ± 0.51bc | 33.7 ± 0.20a | 1312 ± 7.7a | 23.1 ± 0.14a–d | 23.7 ± 0.14b–d | 24.0 ± 0.14b–d | 70.7 ± 0.41b–d | |

| 12.5 | 90.5 ± 0.53b | 34.7 ± 0.20a | 1340 ± 7.8a | 23.5 ± 0.14a–c | 24.1 ± 0.14bc | 24.8 ± 0.14bc | 72.3 ± 0.42bc | |

| 15 | 87.6 ± 0.51bc | 31.7 ± 0.19ab | 1215 ± 7.1b | 22.6 ± 0.13b–e | 23.1 ± 0.14b–e | 23.7 ± 0.14b–d | 69.3 ± 0.40b–e | |

| Mean | 84.7 ± 1.5A | 31.3 ± 0.78A | 1222 ± 24.5A | 22.2 ± 0.34A | 23.1 ± 0.42A | 23.8 ± 0.46A | 69.0 ± 1.20A | |

| FYM | 0 | 73.9 ± 0.43i–k | 24.8 ± 0.14e–g | 1037 ± 6.1d–f | 19.4 ± 0.11j | 20.2 ± 0.12h–j | 21.3 ± 0.12e–h | 60.9 ± 0.36h–j |

| 2.5 | 75.7 ± 0.44hi | 24.8 ± 0.14e–g | 1041 ± 6.1d–f | 19.7 ± 0.12ij | 20.6 ± 0.12g–i | 21.5 ± 0.13e–g | 61.8 ± 0.36g–j | |

| 5 | 78.3 ± 0.46gh | 25.7 ± 0.15d–g | 1059 ± 6.2d–f | 20.8 ± 0.12g–i | 21.3 ± 0.12f–h | 22.0 ± 0.13d–f | 64.1 ± 0.37f–i | |

| 7.5 | 82.4 ± 0.48ef | 28.7 ± 0.17b–d | 1157 ± 6.8bc | 22.3 ± 0.13c–f | 22.7 ± 0.13c–f | 23.2 ± 0.14c–e | 68.1 ± 0.40c–f | |

| 10 | 86.4 ± 0.50cd | 31.7 ± 0.19ab | 1301 ± 7.6a | 23.7 ± 0.14ab | 24.7 ± 0.14b | 25.6 ± 0.15b | 74.0 ± 0.43b | |

| 12.5 | 85.6 ± 0.50c–e | 29.7 ± 0.17bc | 1217 ± 7.1b | 22.1 ± 0.13d–f | 22.7 ± 0.13c–f | 23.1 ± 0.14c–e | 67.8 ± 0.40c–f | |

| 15 | 83.2 ± 0.49d–f | 26.7 ± 0.16c–f | 1110 ± 6.5cd | 21.6 ± 0.13e–g | 22.2 ± 0.13d–g | 22.8 ± 0.13ab | 66.4 ± 0.39d–g | |

| Mean | 80.8 ± 1.0AB | 27.4 ± 0.55AB | 1132 ± 20.7AB | 21.4 ± 0.31AB | 22.0 ± 0.32AB | 22.7 ± 0.31C–E | 66.1 ± 0.93AB | |

| Comp | 0 | 62.3 ± 0.36n | 24.8 ± 0.14e–f | 726 ± 4.2i | 14.6 ± 0.08m | 15.1 ± 0.09l | 16.0 ± 0.09l | 45.7 ± 0.27n |

| 2.5 | 64.9 ± 0.38mn | 19.8 ± 0.12i | 796 ± 4.6hi | 15.6 ± 0.09m | 16.1 ± 0.09kl | 16.7 ± 0.10l | 48.5 ± 0.28mn | |

| 5 | 67.7 ± 0.40lm | 20.8 ± 0.12hi | 872 ± 5.1g | 16.8 ± 0.10l | 17.2 ± 0.10k | 17.7 ± 0.10kl | 51.8 ± 0.30lm | |

| 7.5 | 71.3 ± 0.42j–l | 22.8 ± 0.13g–i | 1028 ± 6.0ef | 18.1 ± 0.11k | 18.7 ± 0.11j | 19.2 ± 0.11h–k | 56.0 ± 0.33kl | |

| 10 | 70.9 ± 0.41kl | 23.8 ± 0.14f–h | 1012 ± 5.9f | 19.6 ± 0.11ij | 19.6 ± 0.11ij | 20.1 ± 0.12f–j | 59.3 ± 0.35i–k | |

| 12.5 | 73.0 ± 0.43i–k | 25.7 ± 0.15d–g | 1080 ± 6.3d–f | 20.2 ± 0.12h–j | 20.7 ± 0.12g–i | 21.3 ± 0.12e–i | 62.2 ± 0.36g–j | |

| 15 | 68.7 ± 0.40l | 22.8 ± 0.13g–i | 839 ± 4.9gh | 19.4 ± 0.11j | 19.1 ± 0.11ij | 19.6 ± 0.11g–k | 58.1 ± j0.34k | |

| Mean | 68.4 ± 0.8B | 22.9 ± 0.44B | 908 ± 27.7B | 17.8 ± 0.45B | 18.1 ± 0.41B | 18.7 ± 0.40B | 54.5 ± 1.25B | |

| Organic Amendment | Cobalt | N | P | K | Mn | Zn | Cu | Fe | Co |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg kg−1) | (g 100 g−1) | (mg kg−1) | |||||||

| CM | 0 | 2.60 ± 0.02 † g–i | 0.17 ± 0.00h–j | 0.95 ± 0.01i–k | 106 ± 0.6b–e | 64 ± 0.4g | 11.6 ± 0.07e | 277 ± 1.6a | 1.34 ± 0.01fg |

| 2.5 | 2.73 ± 0.02f–h | 0.24 ± 0.00fg | 1.21 ± 0.01e–g | 113 ± 0.7b–d | 66 ± 0.4d–g | 12.4 ± 0.07d | 268 ± 1.6a–c | 1.66 ± 0.01e–g | |

| 5 | 3.50 ± 0.02b–d | 0.28 ± 0.00cd | 1.45 ± 0.01bc | 118 ± 0.7bc | 69 ± 0.4b | 13.4 ± 0.08bc | 263 ± 1.5a–d | 1.86 ± 0.01e–g | |

| 7.5 | 3.89 ± 0.02a | 0.32 ± 0.00ab | 1.62 ± 0.01a | 125 ± 0.7b | 71 ± 0.4a | 14.3 ± 0.08a | 248 ± 1.4c–f | 7.14 ± 0.04b | |

| 10 | 3.89 ± 0.02a | 0.33 ± 0.00a | 1.62 ± 0.01a | 125 ± 0.7b | 71 ± 0.4a | 14.3 ± 0.08a | 256 ± 1.5a–f | 4.31 ± 0.03c–e | |

| 12.5 | 3.72 ± 0.02ab | 0.32 ± 0.00a–c | 1.60 ± 0.01a | 121 ± 0.7b | 69 ± 0.4b | 13.9 ± 0.08ab | 240 ± 1.4e–g | 9.47 ± 0.06ab | |

| 15 | 3.56 ± 0.02bc | 0.27 ± 0.00d–f | 1.57 ± 0.01ab | 119 ± 0.7bc | 68 ± 0.4bc | 13.3 ± 0.08bc | 240 ± 1.4e–g | 11.60 ± 0.07 | |

| Mean | 3.41 ± 0.11A | 0.28 ± 0.01A | 1.43 ± 0.05A | 118 ± 1.4AB | 68 ± 0.6A | 13.3 ± 0.21A | 256 ± 3.0AB | 5.34 ± 0.86AB | |

| FYM | 0 | 2.60 ± 0.02g–i | 0.17 ± 0.00ij | 0.95 ± 0.01i–k | 106 ± 0.6b–e | 64 ± 0.4g | 11.6 ± 0.07e | 277 ± 1.6a | 1.34 ± 0.01fg |

| 2.5 | 2.65 ± 0.02gh | 0.19 ± 0.00hi | 1.08 ± 0.01g–i | 108 ± 0.6b–e | 65 ± fg | 12.4 ± 0.07d | 275 ± 1.6a | 1.46 ± 0.01fg | |

| 5 | 2.99 ± 0.02ef | 0.21 ± 0.00hi | 1.13 ± 0.01f–h | 111 ± 0.7b–d | 66 ± 0.4d–f | 13.1 ± 0.08c | 267 ± 1.6a–d | 4.14 ± 0.02c–f | |

| 7.5 | 3.24 ± 0.02de | 0.24 ± 0.00ef | 1.26 ± 0.01d–f | 164 ± 1.0a | 67 ± 0.4c–d | 13.7 ± 0.08a–c | 261 ± 1.5a–e | 6.83 ± 0.04bc | |

| 10 | 3.56 ± 0.02bc | 0.29 ± 0.00b–d | 1.39 ± 0.01cd | 166 ± 1.0a | 67 ± 0.4cd | 13.9 ± 0.08ab | 245 ± 1.4d–f | 10.28 ± 0.06a | |

| 12.5 | 3.56 ± 0.02bc | 0.30 ± 0.00a–d | 1.44 ± 0.01c | 168 ± 1.0a | 68 ± 0.4bc | 14.2 ± 0.08a | 255 ± 1.5a–f | 9.19 ± 0.05ab | |

| 15 | 3.42 ± 0.02cd | 0.28 ± 0.00de | 1.33 ± 0.01c–e | 162 ± 1.0a | 65 ± 0.4e–g | 13.3 ± 0.08bc | 252 ± 1.5b–f | 11.42 ± 0.07a | |

| Mean | 3.14 ± 0.08AB | 0.24 ± 0.01AB | 1.22 ± 0.04AB | 141 ± 6.2A | 66 ± 0.3AB | 13.3 ± 0.19A | 262 ± 2.5A | 6.38 ± 0.86A | |

| Comp | 0 | 2.08 ± 0.01j | 0.13 ± 0.00j | 0.76 ± 0.01l | 85 ± 0.5ef | 51 ± 0.3j | 9.3 ± 0.05h | 221 ± 1.3g | 1.07 ± 0.01g |

| 2.5 | 2.37 ± 0.01ij | 0.16 ± 0.00ij | 0.85 ± 0.01kl | 78 ± 0.5f | 53 ± 0.3ij | 8.9 ± 0.05h | 273 ± 1.6ab | 1.43 ± 0.01fg | |

| 5 | 2.50 ± 0.01hi | 0.17 ± 0.00ij | 0.91 ± 0.01j–l | 82 ± 0.5ef | 54 ± 0.3i | 9.3 ± 0.05h | 263 ± 1.5a–d | 1.66 ± 0.01e–g | |

| 7.5 | 2.73 ± 0.02f–h | 0.19 ± 0.00hi | 0.97 ± 0.01i–k | 88d ± 0.5–f | 57 ± 0.3h | 10.0 ± 0.06g | 257 ± 1.5a–f | 4.11 ± 0.02c–f | |

| 10 | 2.86 ± 0.02fg | 0.24 ± 0.00fg | 1.07 ± 0.01g–i | 95c ± 0.6–f | 57 ± 0.3h | 10.5 ± 0.06fg | 238 ± 1.4fg | 10.16 ± 0.05a | |

| 12.5 | 2.99 ± 0.02ef | 0.24 ± 0.00fg | 1.07 ± 0.01g–i | 95 ± 0.6c–f | 58 ± 0.3h | 11.0 ± 0.06ef | 245 ± 1.4d–f | 6.80 ± 0.04bd | |

| 15 | 2.75 ± 0.02f–h | 0.23 ± 0.00fg | 1.01 ± 0.01h–j | 91 ± 0.5d–f | 54 ± 0.3i | 10.2 ± 0.06g | 234 ± 1.4fg | 11.2 ± 0.076a | |

| Mean | 2.61 ± 0.07B | 0.19 ± 0.01B | 0.95 ± 0.02B | 88 ± 1.3B | 55 ± 0.5B | 9.8 ± 0.15B | 247 ± 3.7B | 5.2 ± 0.881B | |

| Organic fertilizer | Cobalt | Proteins | Total Carbohydrates | Total Soluble Solids | Total Phenolics | Carotenoids | Vitamin C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg kg−1) | (g 100 g−1 FW) | (g 100 g−1 FW) | (mg 100 g−1 FW) | ||||

| CM | 0 | 8.5 ± 0.05 † g–i | 25.8 ± 0.15e | 32.2 ± 0.19d | 2.00 ± 0.01ij | 12.0 ± 0.07h | 18.7 ± 0.11d–f |

| 2.5 | 9.0 ± 0.05f–h | 26.6 ± 0.16de | 32.6 ± 0.19cd | 2.06 ± 0.01g–i | 12.9 ± 0.08fg | 19.1 ± 0.11c–e | |

| 5 | 11.5 ± 0.07bc | 27.1 ± 0.16cd | 33.2 ± 0.19a–d | 2.17 ± 0.01e–g | 13.7 ± 0.08b–e | 19.7 ± 0.12a–d | |

| 7.5 | 12.8 ± 0.07a | 29.3 ± 0.17a | 34.7 ± 0.20a | 2.48 ± 0.01a | 14.8 ± 0.09a | 20.8 ± 0.12a | |

| 10 | 12.8 ± 0.07a | 28.4 ± 0.17ab | 33.9 ± 0.20a–c | 2.42 ± 0.01a–c | 14.2 ± 0.08a–c | 20.3 ± 0.12a–c | |

| 12.5 | 12.3 ± 0.07ab | 27.9 ± 0.16bc | 33.5 ± 0.20a–d | 2.31 ± 0.01cd | 13.9 ± 0.08b–d | 19.6 ± 0.11a–e | |

| 15 | 11.7 ± 0.07bc | 27. 7 ± 0.16bc | 32.3 ± 0.19d | 2.27 ± 0.01d–f | 13.5 ± 0.08d–f | 18.4 ± 0.11e–g | |

| Mean | 11.2 ± 0.37A | 27.6 ± 0.24A | 33.2 ± 0.20A | 2.2 ± 0.044A | 13.6 ± 0.19A | 19.5 ± 0.18A | |

| FYM | 0 | 8.5 ± 0.05g–i | 25.7 ± 0.15e | 32.2 ± 0.19d | 2.00 ± 0.01ij | 11.9 ± 0.07h | 18.7 ± 0.11d–f |

| 2.5 | 8.7 ± 0.05gh | 26.4 ± 0.15de | 32.3 ± 0.19d | 2.04 ± 0.01hi | 12.7 ± 0.07g | 18.9 ± 0.11d–f | |

| 5 | 9.8 ± 0.06ef | 26.9 ± 0.16cd | 33.0 ± 0.19b–d | 2.15 ± 0.01e–h | 13.1 ± 0.08e–g | 19.5 ± 0.11b–e | |

| 7.5 | 10.6 ± 0.06de | 27.7 ± 0.16bc | 33.5 ± 0.20a–d | 2.27 ± 0.01de | 13.6 ± 0.08c–e | 19.8 ± 0.12a–d | |

| 10 | 11.7 ± 0.07bc | 29.3 ± 0.17a | 34.2 ± 0.20ab | 2.44 ± 0.01ab | 14.3 ± 0.08ab | 20.6 ± 0.12ab | |

| 12.5 | 11.7 ± 0.07bc | 28.2 ± 0.17b | 33.6 ± 0.20a–d | 2.38 ± 0.01a–d | 13.1 ± 0.08e–g | 18.8 ± 0.11d–f | |

| 15 | 11.3 ± 0.07cd | 27.6 ± 0.16bc | 32.8 ± 0.19b–d | 2.33 ± 0.01b–d | 12.5 ± 0.07gh | 17.8 ± 0.10f–h | |

| Mean | 10.3 ± 0.28B | 27.4 ± 0.25A | 33.1 ± 0.16A | 2.23 ± 0.04A | 13.0 ± 0.17A | 19.2 ± 0.19A | |

| Comp | 0 | 6.4 ± 0.04j | 19.4 ± 0.11i | 23.4 ± 0.14i | 1.49 ± 0.01l | 8.9 ± 0.05k | 14.0 ± 0.08i |

| 2.5 | 7.8 ± 0.05i | 20.3 ± 0.12hi | 25.9 ± 0.15h | 1.76 ± 0.01k | 9.1 ± 0.05k | 15.2 ± 0.09i | |

| 5 | 8.2 ± 0.05hi | 21.5 ± 0.13g | 27.7 ± 0.16fg | 1.90 ± 0.01j | 10.0 ± 0.06j | 16.6 ± 0.10h | |

| 7.5 | 9.0 ± 0.05f–h | 23.0 ± 0.13f | 28.4 ± 0.17ef | 1.95 ± 0.01ij | 10.5 ± 0.06ij | 16.8 ± 0.10h | |

| 10 | 9.4 ± 0.05fg | 21.3 ± 0.12g | 28.4 ± 0.17ef | 2.00 ± 0.01ij | 10.8 ± 0.06i | 17.0 ± 0.10h | |

| 12.5 | 9.8 ± 0.06ef | 22.6 ± 0.13f | 29.3 ± 0.17e | 2.03 ± 0.01hi | 11.1 ± 0.06i | 17.4 ± 0.10gh | |

| 15 | 9.0 ± 0.05f–h | 20.7g ± 0.12h | 26.5 ± 0.16gh | 2.00 ± 0.01 ij | 10.5 ± 0.06ij | 16.7 ± 0.10h | |

| Mean | 8.5 ± 0.24C | 21.2 ± 0.26B | 27.1 ± 0.42B | 1.88 ± 0.04B | 10.1 ± 0.17B | 16.3 ± 0.25B | |

| PH | TLNo | TLA | N | P | K | LNo | LA | Cu | Fe | Co | Pro | TC | TSS | TP | Cars | VIT-C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| TLNo | 0.915 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| TLA | 0.955 ** | 0.904 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| N | 0.938 ** | 0.892 ** | 0.924 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| P | 0.881 ** | 0.869 ** | 0.878 ** | 0.965 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| K | 0.952 ** | 0.933 ** | 0.921 ** | 0.971 ** | 0.948 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Mn | 0.744 ** | 0.627 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.694 ** | 0.657 ** | 0.653 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Zn | 0.928 ** | 0.856 ** | 0.916 ** | 0.826 ** | 0.755 ** | 0.862 ** | 0.719 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| Cu | 0.948 ** | 0.882 ** | 0.915 ** | 0.878 ** | 0.827 ** | 0.893 ** | 0.822 ** | 0.970 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| Fe | −0.045 ns | −0.241 ns | 0.009 ns | −0.190 ns | −0.280 ns | −0.176 ns | 0.001 ns | 0.223 ns | 0.059 ns | 1 | |||||||

| Co | 0.480 ns | 0.375 ns | 0.404 ns | 0.585 ** | 0.624 ** | 0.517 * | 0.496 * | 0.223 ns | 0.379 ns | −0.608 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Pro | 0.938 ** | 0.878 ** | 0.927 ** | 0.999 ** | 0.963 ** | 0.967 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.829 ** | 0.877 ** | −0.160 ns | 0.585 ** | 1 | |||||

| TC | 0.928 ** | 0.813 ** | 0.903 ** | 0.803 ** | 0.718 ** | 0.823 ** | 0.802 ** | 0.976 ** | 0.963 ** | 0.234 ns | 0.262 ns | 0.806 ** | 1 | ||||

| TSS | 0.889 ** | 0.750 ** | 0.900 ** | 0.773 ** | 0.698 ** | 0.779 ** | 0.748 ** | 0.967 ** | 0.935 ** | 0.337 ns | 0.225 ns | 0.784 ** | 0.975 ** | 1 | |||

| TP | 0.943 ** | 0.793 ** | 0.920 ** | 0.938 ** | 0.896 ** | 0.899 ** | 0.791 ** | 0.870 ** | 0.912 ** | 0.015 ns | 0.568 ** | 0.947 ** | 0.888 ** | 0.885 ** | 1 | ||

| Cars | 0.945 ** | 0.883 ** | 0.938 ** | 0.860 ** | 0.803 ** | 0.884 ** | 0.733 ** | 0.976 ** | 0.971 ** | 0.115 ns | 0.316 ns | 0.862 ** | 0.964 ** | 0.954 ** | 0.908 ** | 1 | |

| VIT-C | 0.857 ** | 0.765 ** | 0.892 ** | 0.765 ** | 0.708 ** | 0.765 ** | 0.656 ** | 0.931 ** | 0.898 ** | 0.285 ns | 0.195 ns | 0.776 ** | 0.922 ** | 0.959 ** | 0.869 ** | 0.961 ** | 1 |

| TDW | 0.965 ** | 0.883 ** | 0.956 ** | 0.916 ** | 0.883 ** | 0.909 ** | 0.731 ** | 0.915 ** | 0.937 ** | −0.031 ns | 0.501 * | 0.920 ** | 0.910 ** | 0.907 ** | 0.955 ** | 0.961 ** | 0.917 ** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gad, N.; Sekara, A.; Abdelhamid, M.T. The Potential Role of Cobalt and/or Organic Fertilizers in Improving the Growth, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Moringa oleifera. Agronomy 2019, 9, 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9120862

Gad N, Sekara A, Abdelhamid MT. The Potential Role of Cobalt and/or Organic Fertilizers in Improving the Growth, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Moringa oleifera. Agronomy. 2019; 9(12):862. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9120862

Chicago/Turabian StyleGad, Nadia, Agnieszka Sekara, and Magdi T. Abdelhamid. 2019. "The Potential Role of Cobalt and/or Organic Fertilizers in Improving the Growth, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Moringa oleifera" Agronomy 9, no. 12: 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9120862

APA StyleGad, N., Sekara, A., & Abdelhamid, M. T. (2019). The Potential Role of Cobalt and/or Organic Fertilizers in Improving the Growth, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Moringa oleifera. Agronomy, 9(12), 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9120862