Physiological Changes in and Transcriptome Responses of Asterothamnus centraliasiaticus Leaves in Response to Drought Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials, Drought Stress Procedures

2.2. Experimental Method

2.2.1. Measurement of Physiological Indices

2.2.2. RNA Extraction and Quality Control

2.2.3. Data Quality Control

2.2.4. Expression Quantification and Differential Expression Analysis

2.2.5. Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) Enrichment Analysis

2.2.6. qPCR Analysis

2.2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

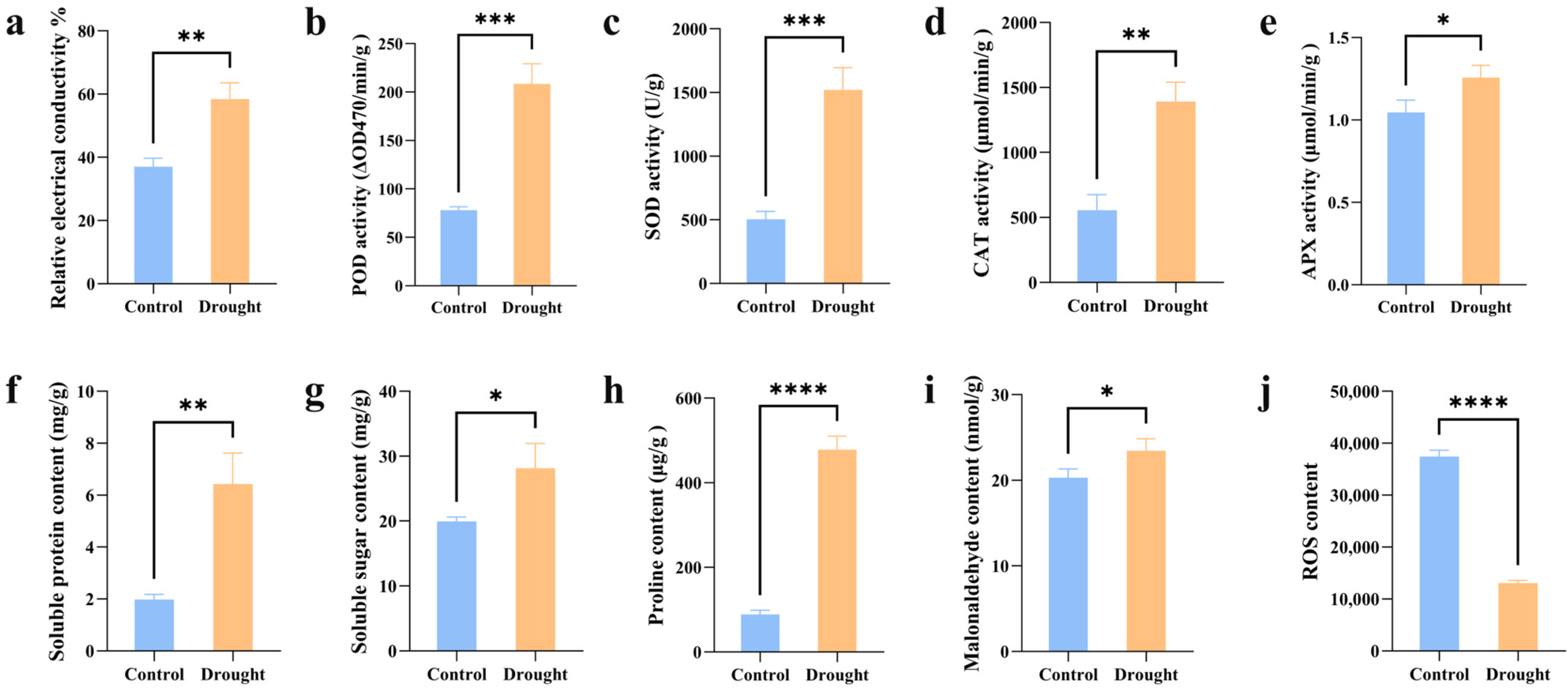

3.1. Analysis of Physiological Changes

3.2. Transcriptome Analysis

3.2.1. Quality Control of Sequencing Data

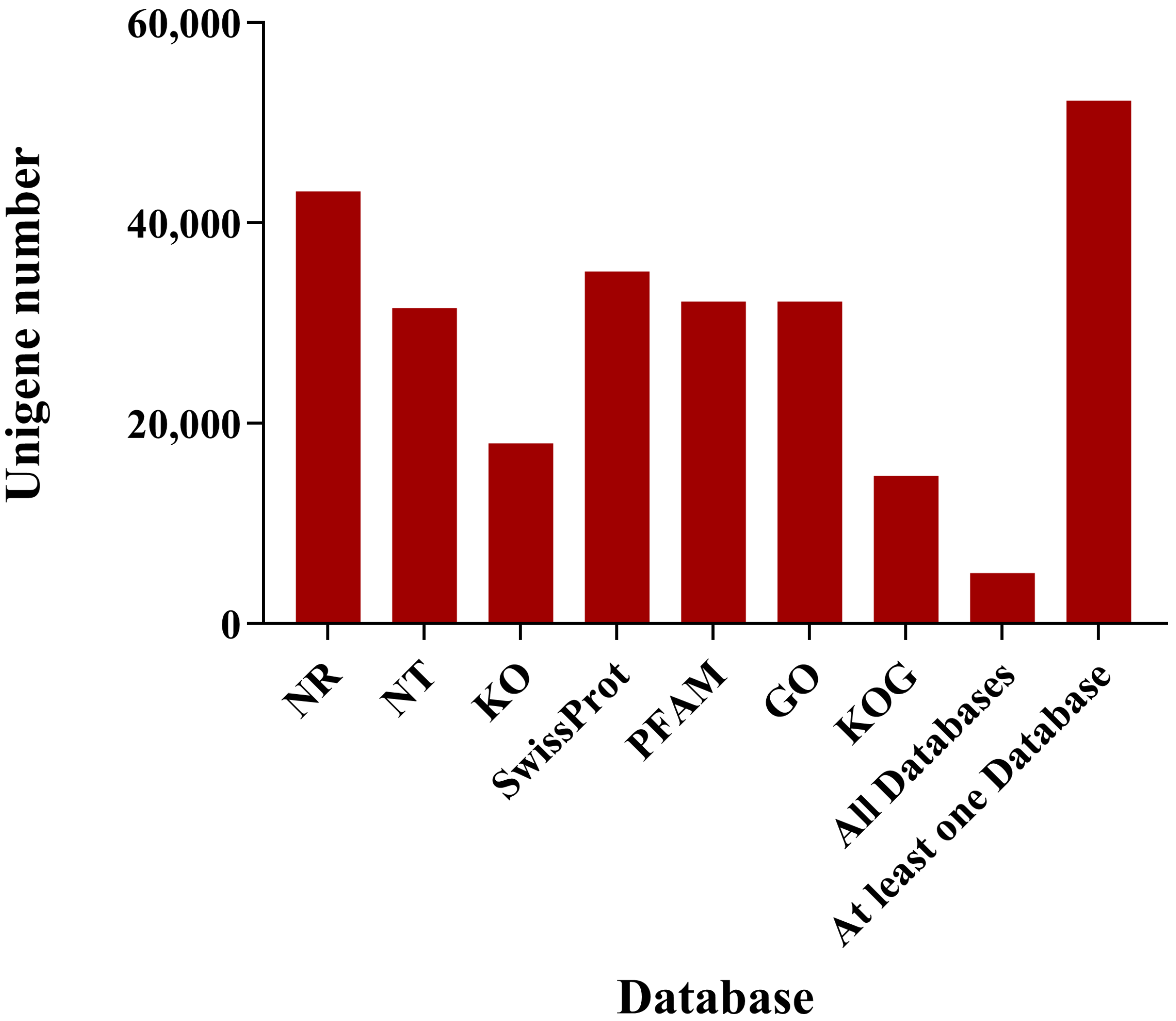

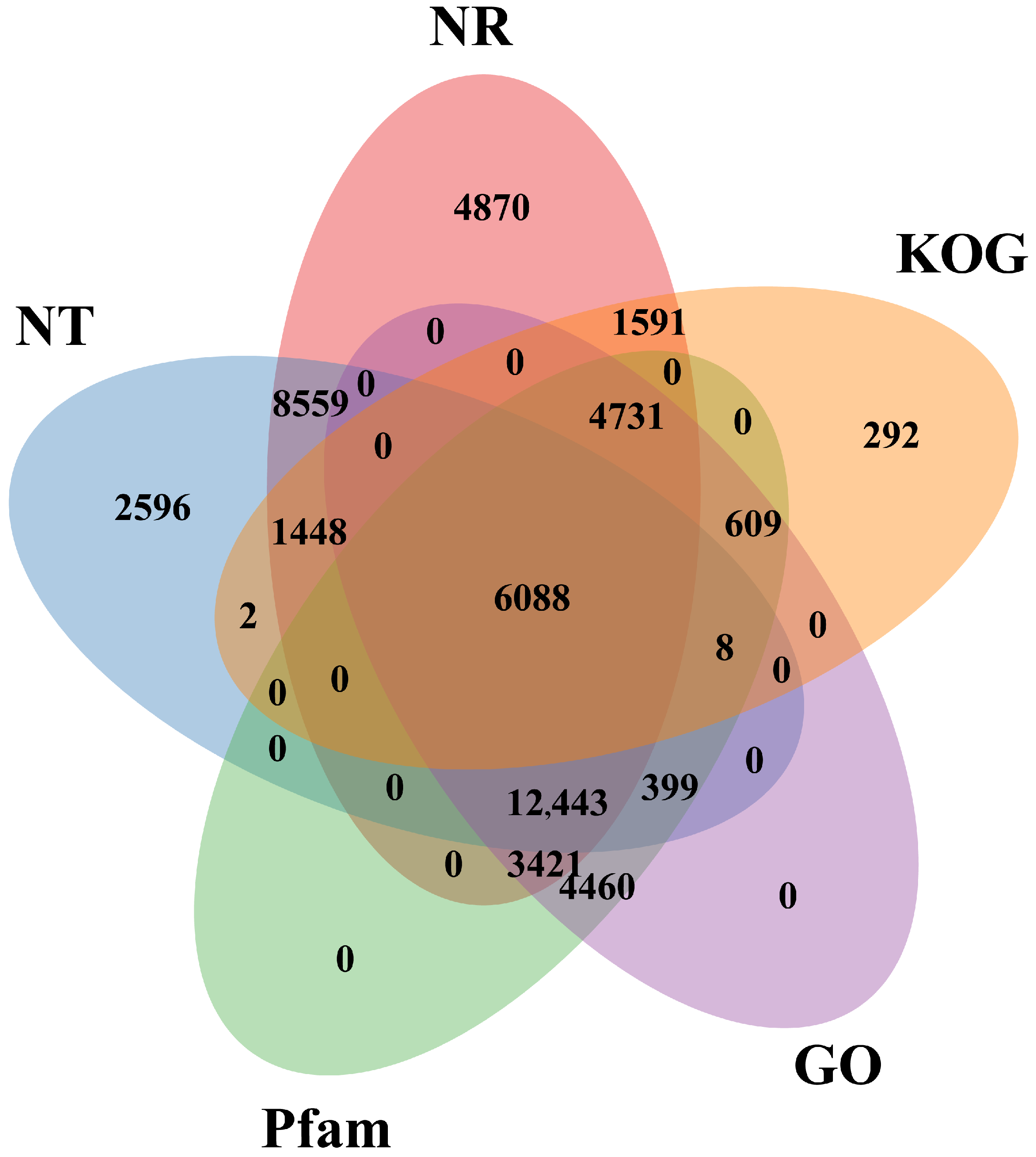

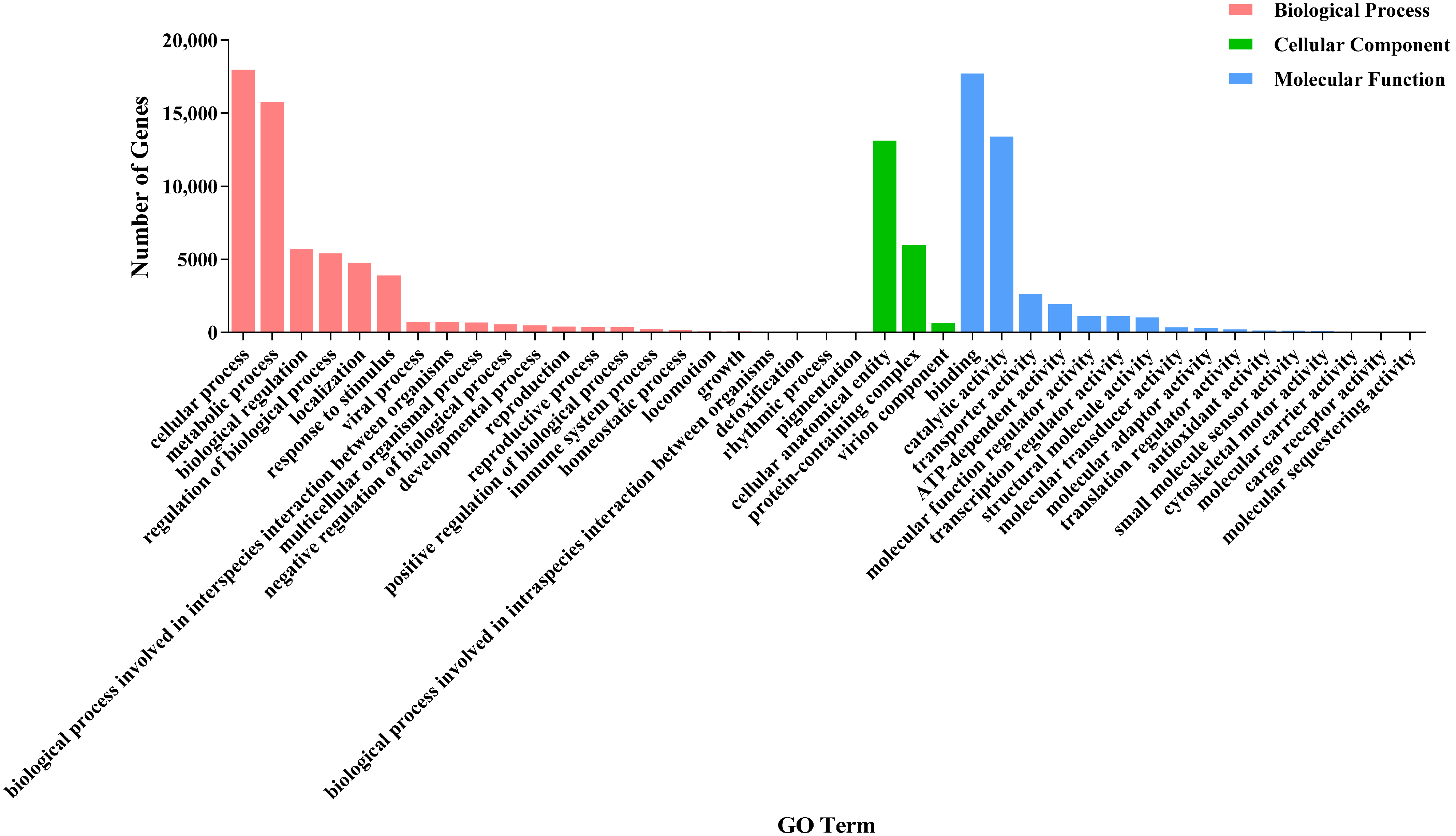

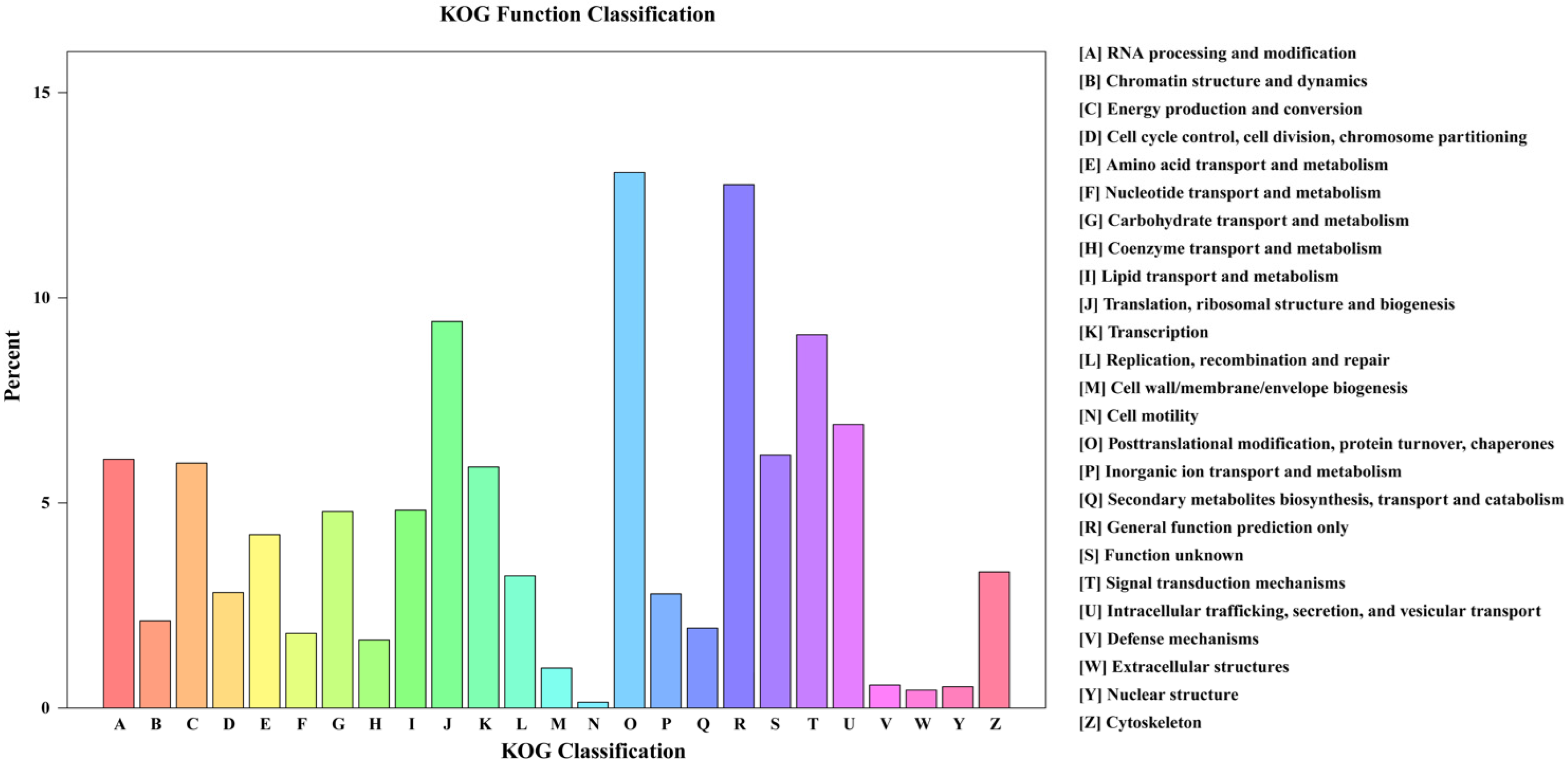

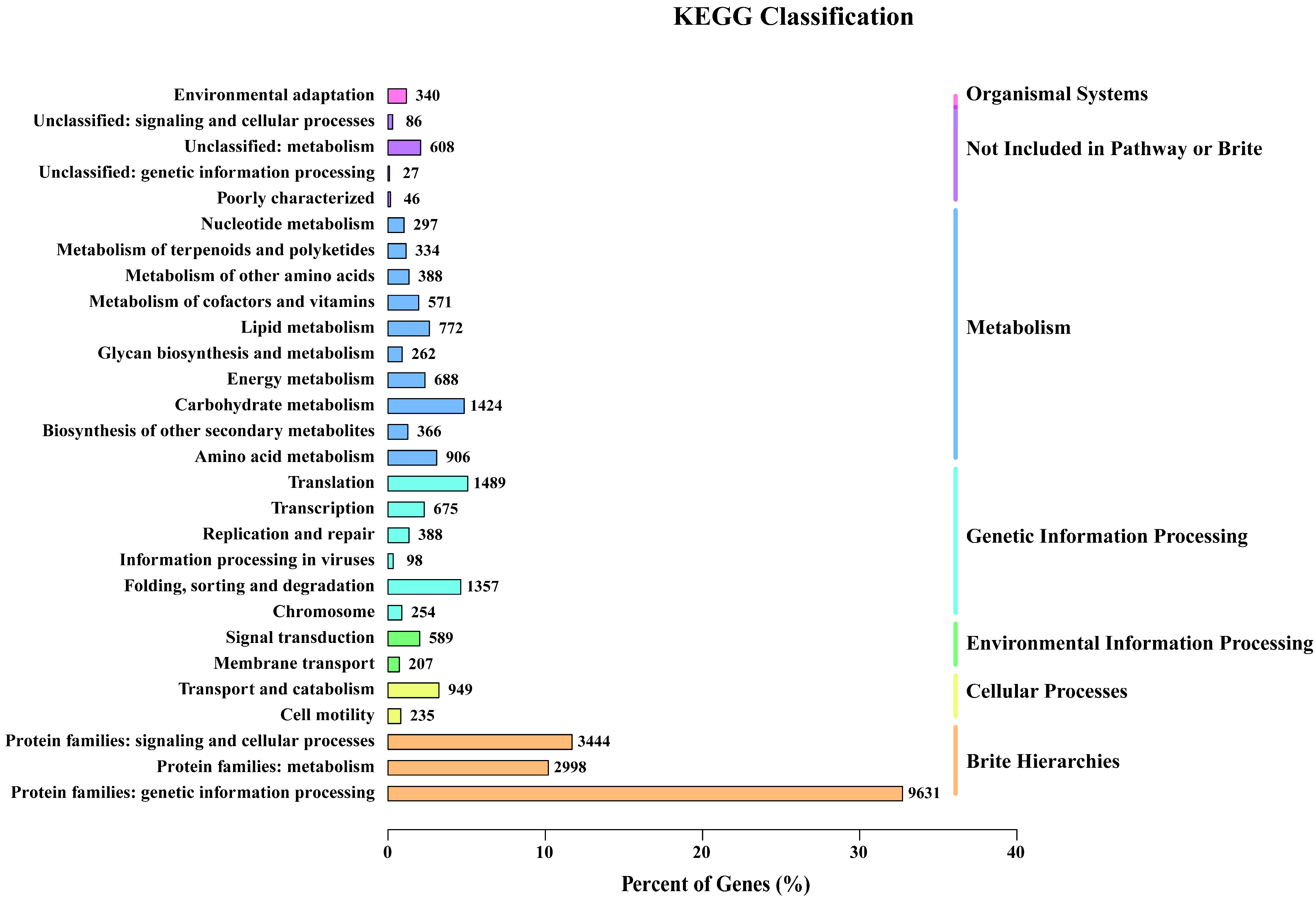

3.2.2. Functional Annotation and Classification of Unigenes

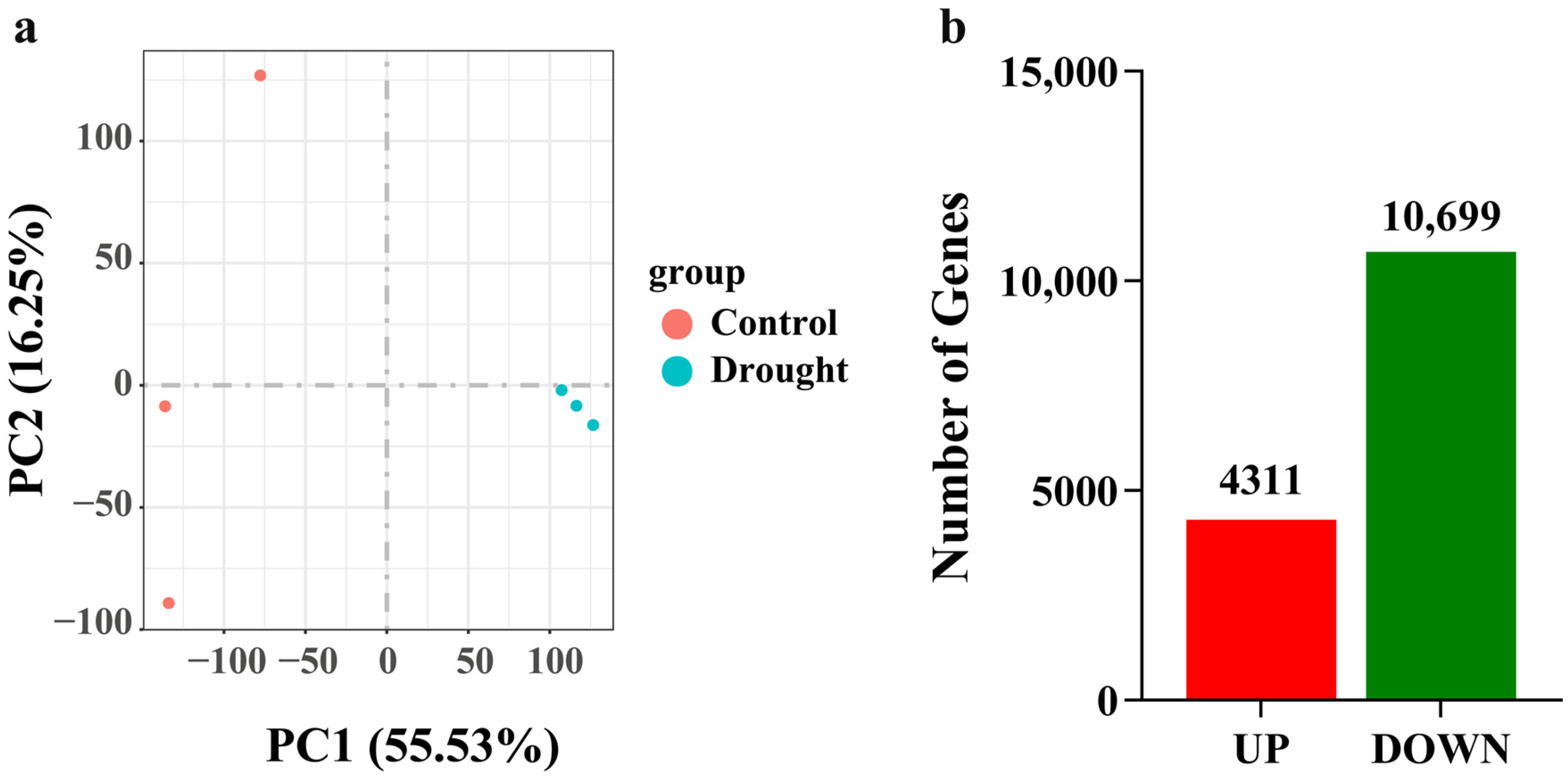

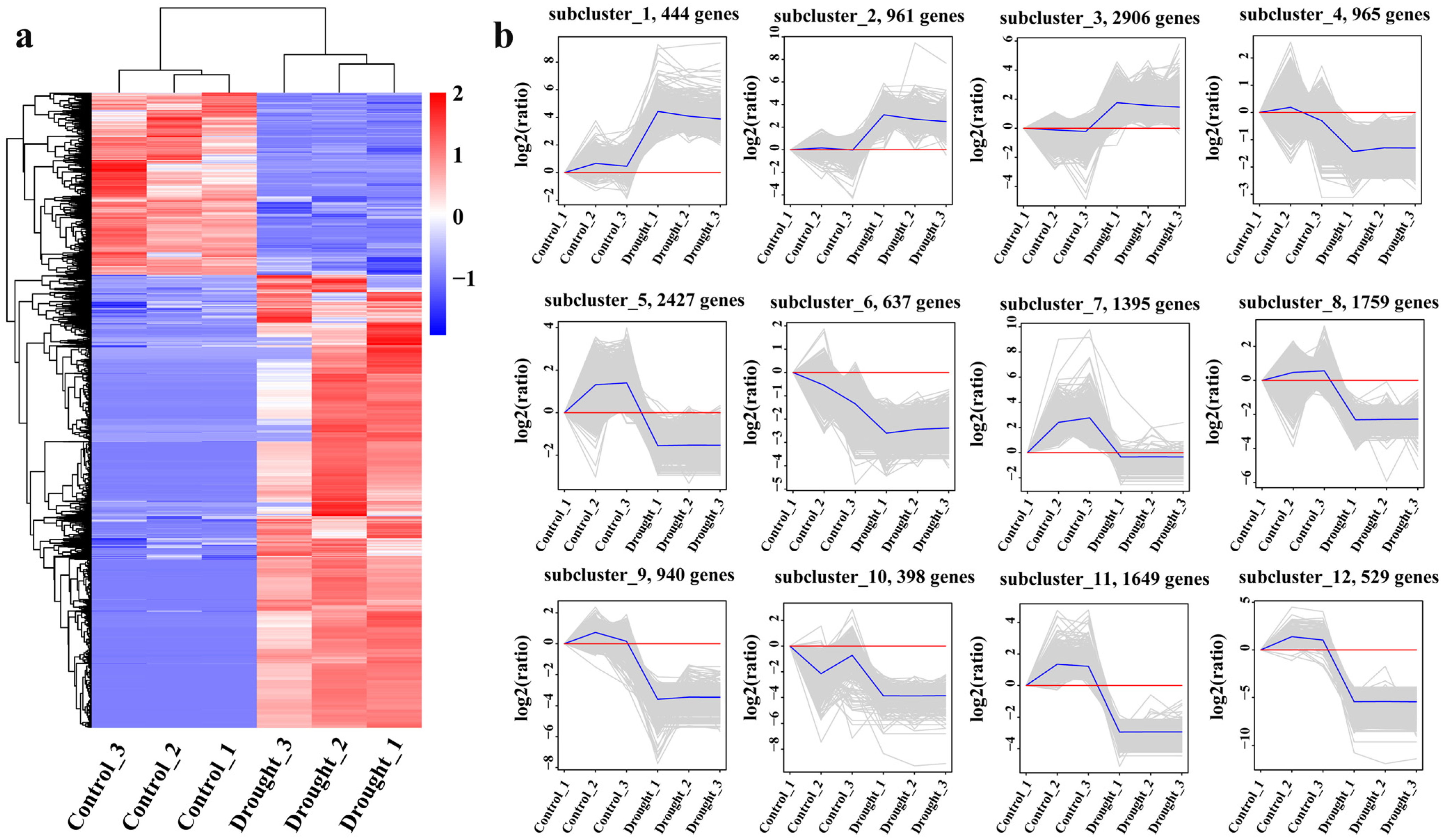

3.2.3. Distribution of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

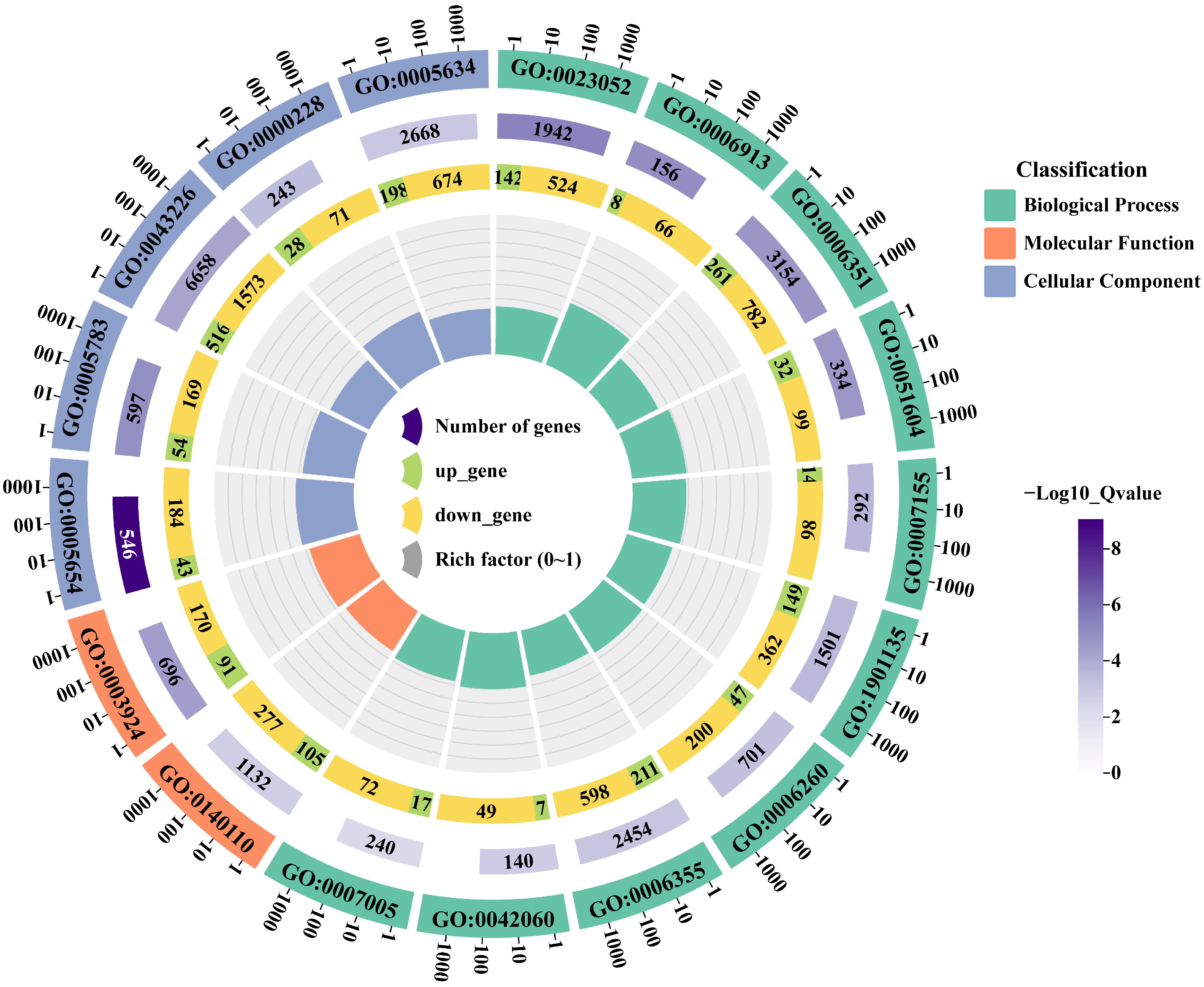

3.2.4. GO Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

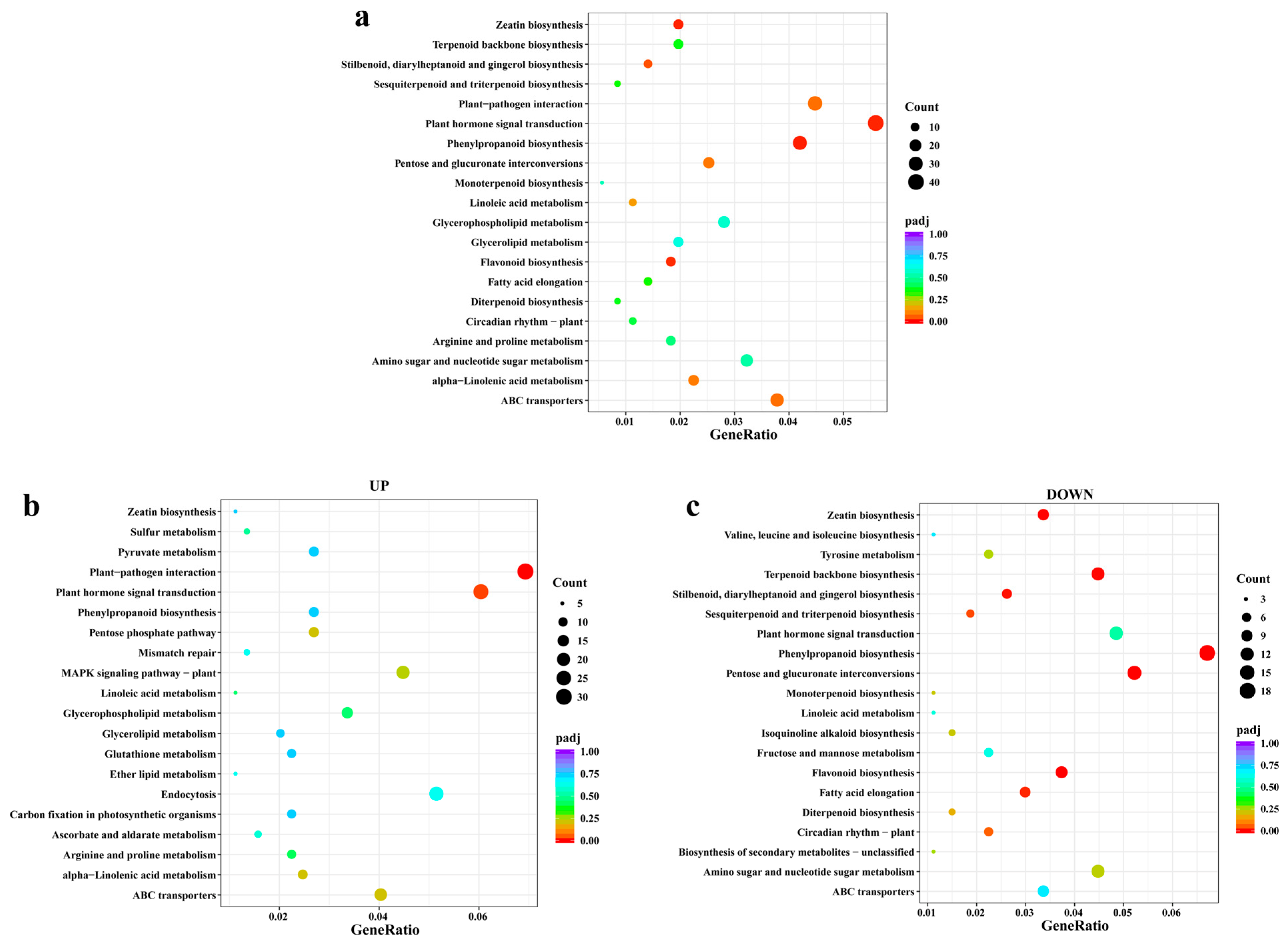

3.2.5. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Metabolic Pathways of DEGs

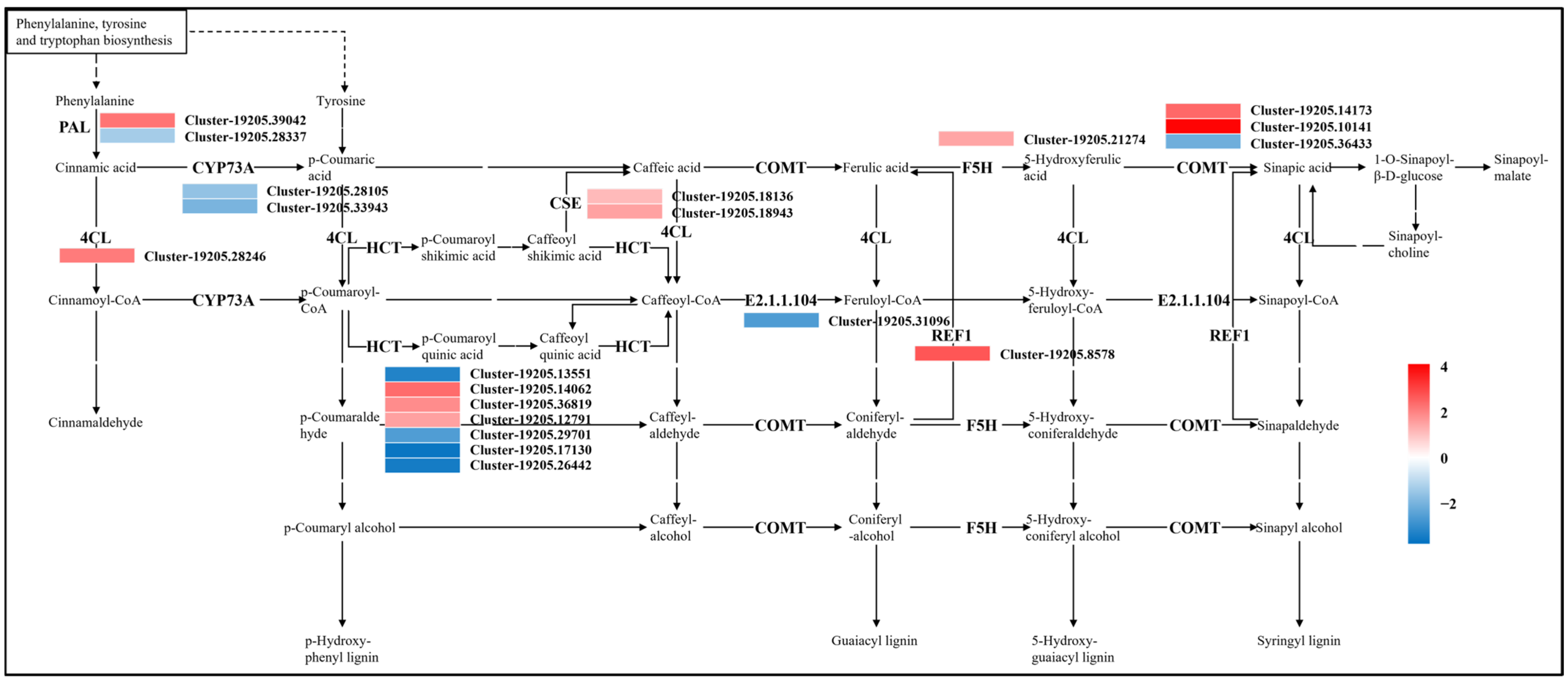

Regulation of Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis

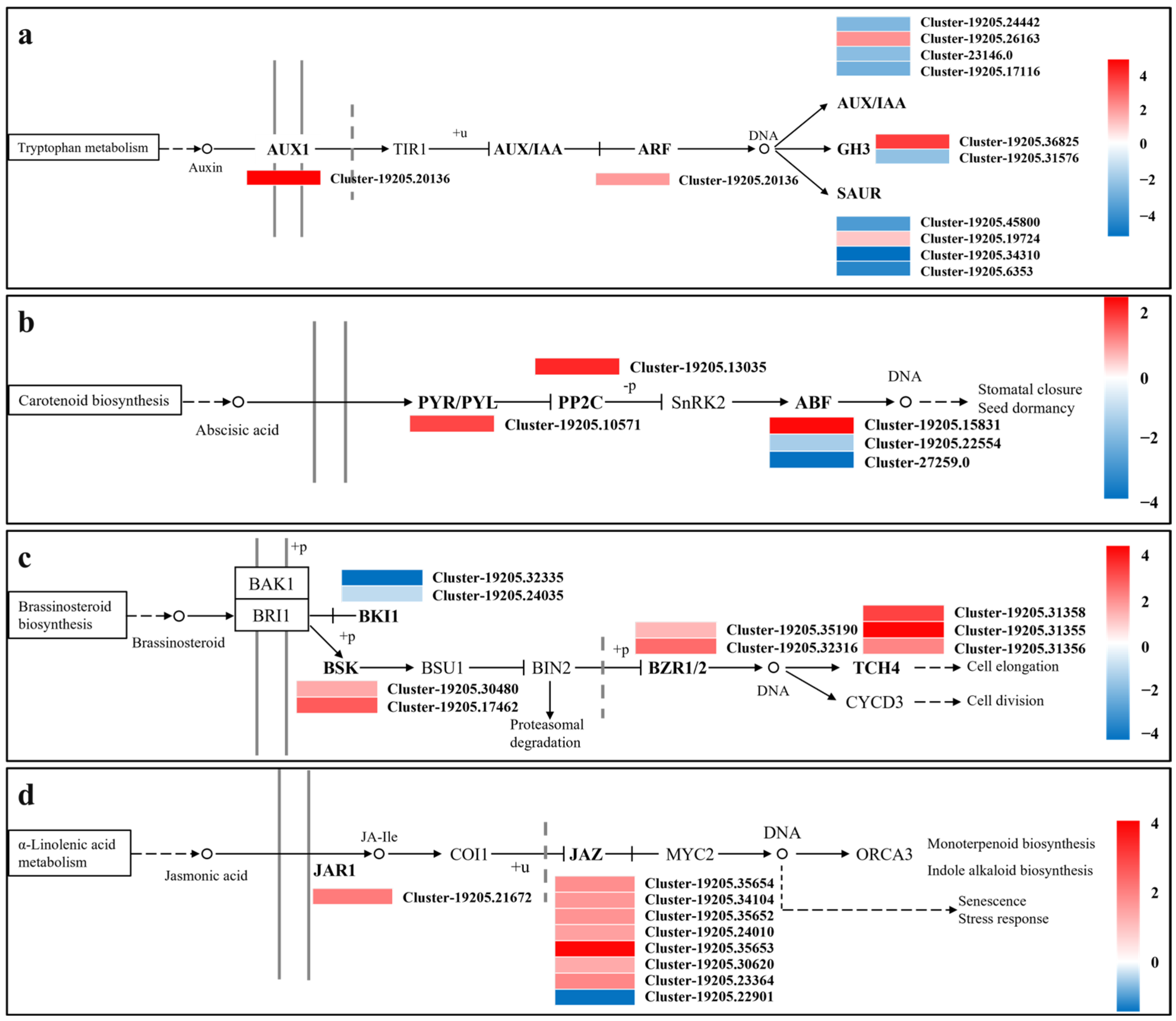

Regulation of Plant Hormone Signal Transduction

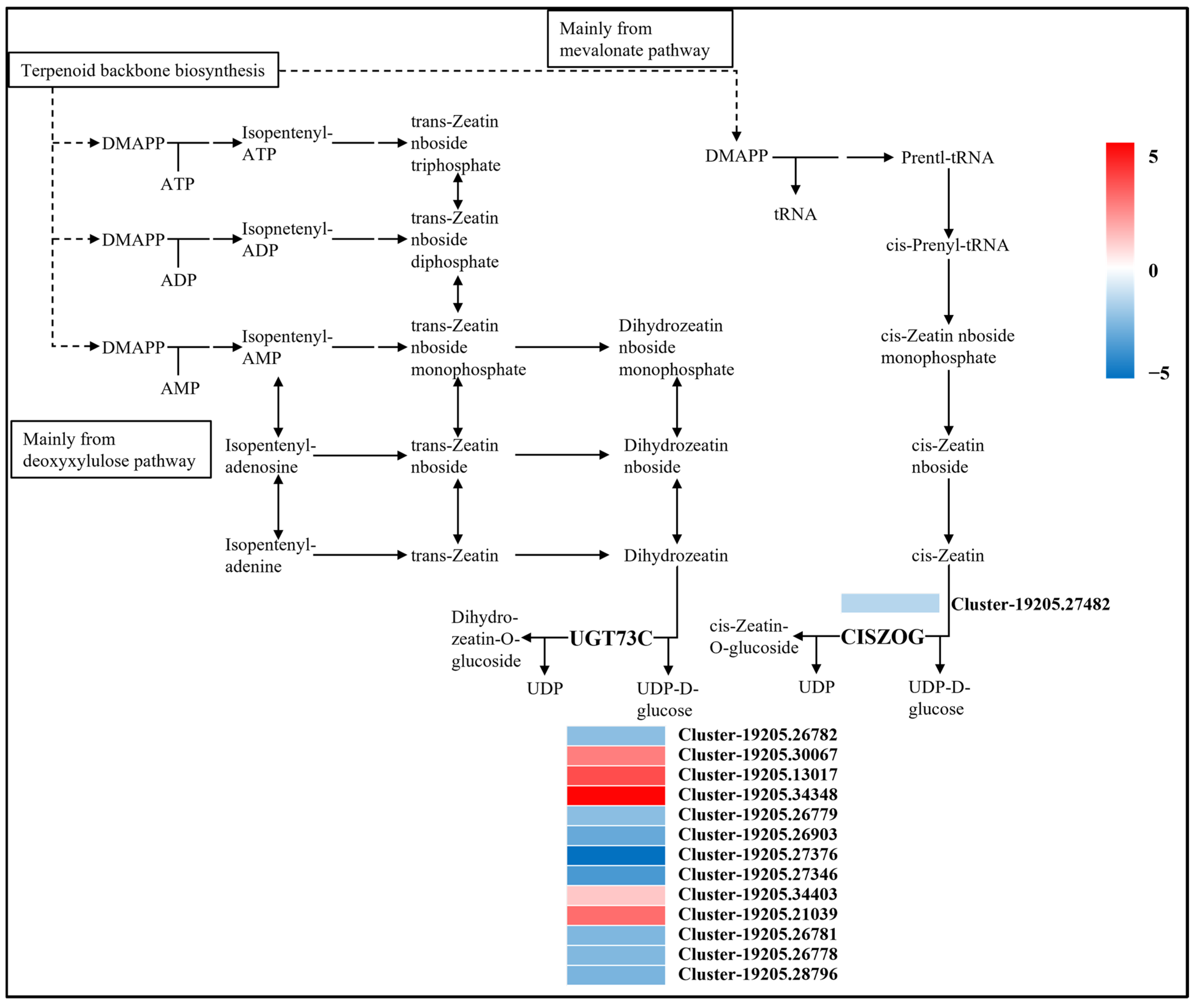

Regulation of Zeatin Biosynthesis

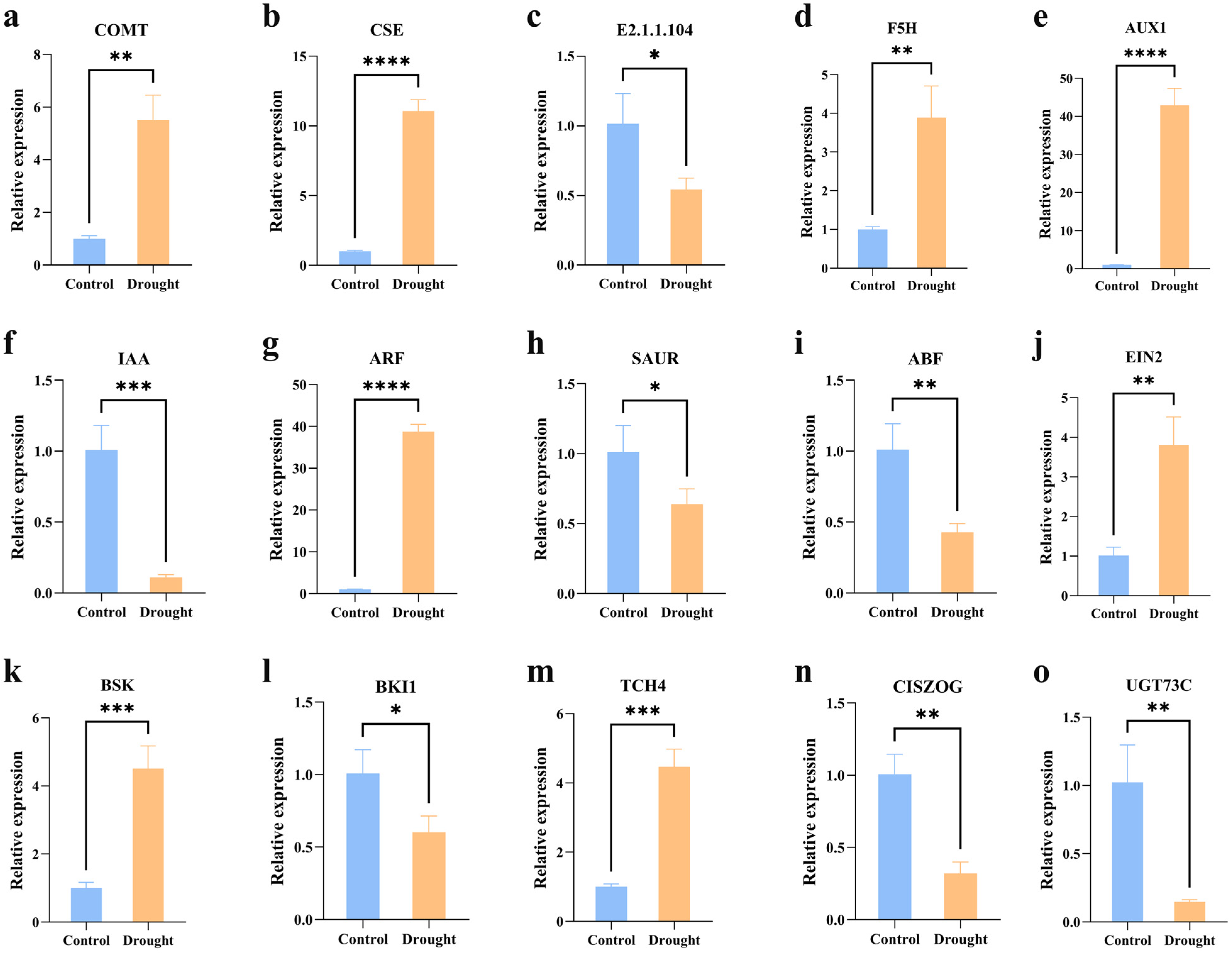

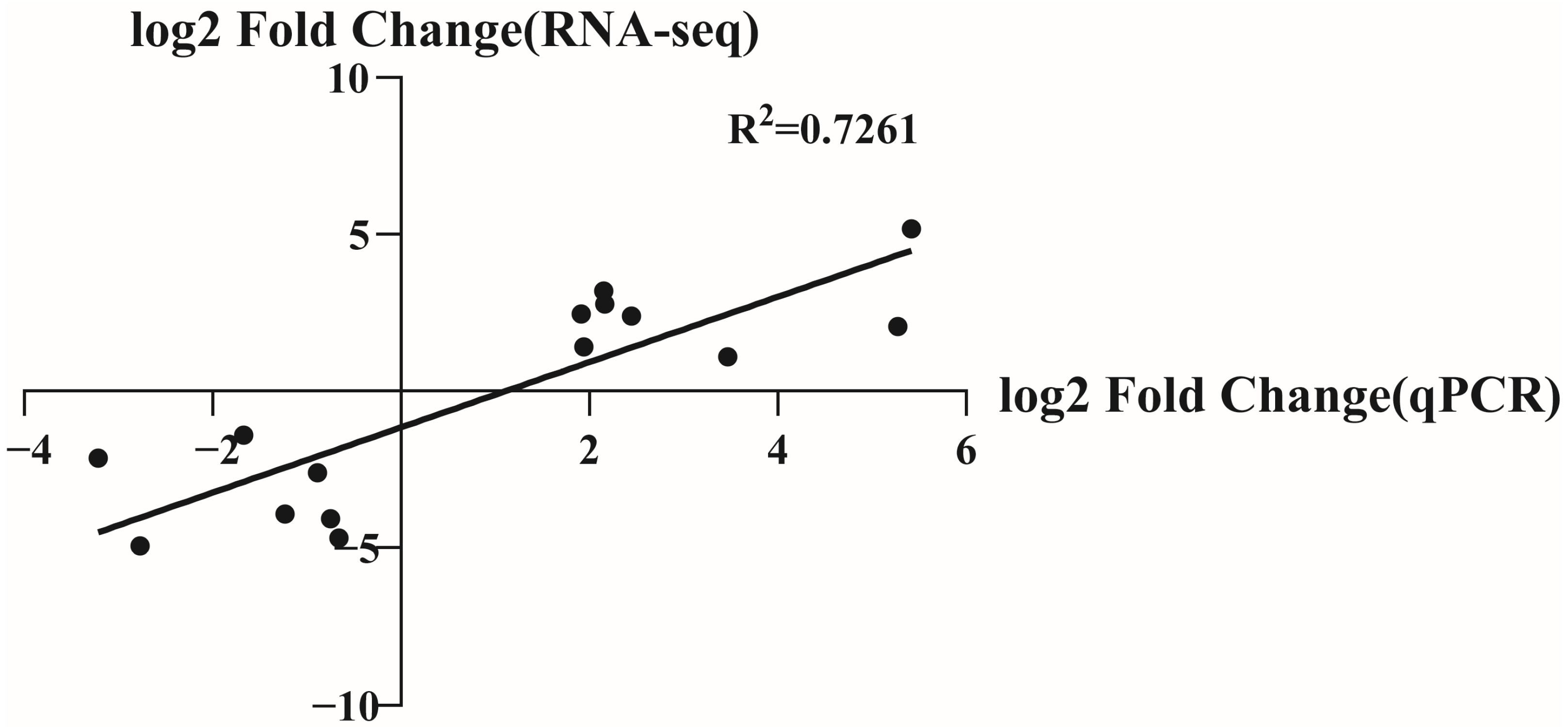

3.3. qPCR Gene Expression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Physiological Changes Under Drought Stress

4.2. Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis Under Drought Stress

4.3. Plant Hormone Signal Transduction Under Drought Stress

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| REC | Relative electrical conductivity |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| SS | Soluble sugar |

| SP | Soluble protein |

| Pro | Proline |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NR | NCBI non-redundant proteins |

| NT | NCBI non-redundant nucleotide database |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| PFAM | Protein family |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| KOG | EuKaryotic Ortholog Groups |

| CC | Cellular component |

| MF | Molecular function |

| BP | Biological process |

| qPCR | Quantitative Real-time PCR |

References

- Maji, A.K.; Das, S.; Marwaha, S.; Kumar, S.; Dutta, S.; Choudhury, M.R.; Arora, A.; Ray, M.; Perumal, A.; Chinusamy, V. Intelligent decision support for drought stress (IDSDS): An integrated remote sensing and artificial intelligence-based pipeline for quantifying drought stress in plants. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 236, 110477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.W.; Wang, X.X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, D.Q.; Tao, J. Effects of fulvic acid on the photosynthetic and physiological characteristics of Paeonia ostii under drought stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1774714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Boubakri, H.; Chen, B.; Farooq, M.; Yang, T.; Liu, Q.; Fan, J. Pretreatment approaches for mitigating drought stress in plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 184, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Shi, M.F.; Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.N.; Qin, S.H.; Kang, Y.C. Dynamics of physiological and biochemical effects of heat, drought and combined stress on potato seedlings. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Ruan, J.; Zhou, R.; Bai, Y.; Liu, M.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z. Screening and Verification of Aquaporin Gene AsPIP1-3 in Garlic (Allium sativum L.) under Salt and Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Guo, H.L.; Yan, L.P.; Gao, L.; Zhai, S.S.; Xu, Y. Physiological, Photosynthetic and Stomatal Ultrastructural Responses of Seedlings to Drought Stress and Rewatering. Forests 2024, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lu, X.; Sun, Y.; Yu, J.; Cao, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Jiang, N.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y. Studies on the physiological response of Hemerocallis middendorffii to two types of drought stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.J.; Kim, J.W.; Begum, M.K.; Sohel, M.A.T.; Lim, Y.-S. Physiological and biochemical changes in sugar beet seedlings to confer stress adaptability under drought condition. Plants 2020, 9, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Waraich, E.A.; Akhtar, S.; Anjum, S.; Ahmad, T.; Mahboob, W.; Hafeez, O.B.A.; Tapera, T.; Labuschagne, M.; Rizwan, M. Physiological responses of wheat to drought stress and its mitigation approaches. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Abdi, G.; Saleem, M.H.; Ali, B.; Ullah, S.; Shah, W.; Mumtaz, S.; Yasin, G.; Muresan, C.C.; Marc, R.A. Plants’ physio-biochemical and phyto-hormonal responses to alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress: A comprehensive review. Plants 2022, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qiu, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yan, D.; Zheng, B. Spermidine induces physiological and biochemical changes in southern highbush blueberry under drought stress. Braz. J. Bot. 2017, 40, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakoula, A.; Therios, I.; Chatzissavvidis, C. Effect of lead and copper on photosynthetic apparatus in citrus (Citrus aurantium L.) plants. The role of antioxidants in oxidative damage as a response to heavy metal stress. Plants 2021, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloudsley-Thompson, J.L. Problems of desertification. Nature 1977, 270, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Yang, L.; Long, X.; Guan, C.; Zhao, C.; Chen, N. Quantifying desertification in the Qinghai Lake Basin. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1309757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Luo, X.; Ma, Q.; Jiang, W.; Xia, H. Desertification caused by embankment construction in permafrost environment on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Yue, C.; Liu, Z. Desertification dynamics and future projections in Qaidam Basin, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jia, H.; Pen, M.; Liu, N.; Wei, J.; Zhou, B. Ecological niche and interspecific association of plant communities in alpine desertification grasslands: A case study of Qinghai Lake Basin. Plants 2022, 11, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Odorico, P.; Bhattachan, A.; Davis, K.F.; Ravi, S.; Runyan, C.W. Global desertification: Drivers and feedbacks. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 51, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Wu, B.; Jia, X.; Xie, S. Wind-proof and sand-fixing effects of Artemisia ordosica with different coverages in the Mu Us Sandy Land, northern China. J. Arid Land 2022, 14, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Tariq, A.; Zhang, Z.; Nazim, M.; Graciano, C.; Sardans, J.; Dong, X.; Gao, Y.; Peñuelas, J.; Zeng, F. Afforestation With Xerophytic Shrubs Promoted Soil Organic Carbon Stability in a Hyper-Arid Environment of Desert. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of Asterothamnus centraliasiaticus Novopokr. (Asteraceae: Asterothamnus). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2024, 9, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y. Isolation by environment overrides isolation by distance in Asterothamnus centraliasiaticus across the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 63, e03867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onda, Y.; Mochida, K. Exploring genetic diversity in plants using high-throughput sequencing techniques. Curr. Genom. 2016, 17, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loraine, A.E.; McCormick, S.; Estrada, A.; Patel, K.; Qin, P. RNA-seq of Arabidopsis pollen uncovers novel transcription and alternative splicing. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1092–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, C.S.; Sousa, A.G.; Barros, P.M.; Kermanov, A.; Becker, J.D. Cell-type-specific alternative splicing in the Arabidopsis germline. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, C.; Li, X.; Wu, K.; Lin, M.; Sun, W. Integrated analysis of physiological responses and transcriptome of cotton seedlings under drought stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xia, C.; Xia, Z.; Zhou, X.; Huang, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Casteel, S.; Zhang, C. Physiological and transcriptomic responses of reproductive stage soybean to drought stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Wan, S.; Zhang, T.; Yan, C.; Shan, S. Transcriptomic analysis and discovery of genes in the response of Arachis hypogaea to drought stress. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 45, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollier, J.; Vanden Bossche, R.; Rischer, H.; Goossens, A. Selection and validation of reference genes for transcript normalization in gene expression studies in Catharanthus roseus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 83, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nxele, X.; Klein, A.; Ndimba, B.K. Drought and salinity stress alters ROS accumulation, water retention, and osmolyte content in sorghum plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 108, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SINGES, S.; Nicolson, G. The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science 1972, 175, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodish, H.F.; Berk, A.; Kaiser, C.; Krieger, M.; Bretscher, A.; Ploegh, H.L.; Martin, K.C.; Yaffe, M.B.; Amon, A. Molecular Cell Biology; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Razi, K.; Muneer, S. Drought stress-induced physiological mechanisms, signaling pathways and molecular response of chloroplasts in common vegetable crops. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 669–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihashemi, S.; Sofo, A. The effect of polyethylene glycol-induced drought stress on photosynthesis, carbohydrates and cell membrane in Stevia rebaudiana grown in greenhouse. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Yuan, F.; Sun, X.; Fu, J. Review on physiological and molecular mechanisms for enhancing salt tolerance in turfgrass. Grass Res. 2024, 4, e024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.-J.; Chen, N.-L.; Li, J.-X.; Zhang, K.; Guo, Y.-H.; Fang, C.-Y. Response of stomatal conductance and osmotic adjustment substances accumulation to rapid drough stress in tomato leaves. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2013, 21, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Guo, Z.; Sun, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, F.; Chen, Y. Role of proline in regulating turfgrass tolerance to abiotic stress. Grass Res. 2023, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, H.M.; He, J.; Arshad, M.B.; Wang, M. Characterization of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase genes in soybean: Genomic insights and expression analysis under abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanbakuyi, F.; Chaichi, M.; Razavi, K.; Sanjarian, F. Tissue-Specific Antioxidant Responses and PAL Gene Expression in Bread Wheat Under Drought Stress. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, e4005. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.-L.; Gao, Y.-L.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.-X. Identification and expression analysis of Jr4CLs gene family based on transcriptome and physiological data in Walnut (Juglans regia). Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 104, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhan, Y.; Zeng, F. Fraxinus mandshurica 4-coumarate-CoA ligase 2 enhances drought and osmotic stress tolerance of tobacco by increasing coniferyl alcohol content. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 155, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, T.; Duan, R.; Luo, Z.; Jiao, P.; Liu, S.; Guan, S. The Zm4CL2 gene regulates drought stress response in Zea mays L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.-C.; Xiong, X.-P.; Zhang, X.-L.; Feng, H.-J.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.-J. Characterization of the Gh4CL gene family reveals a role of Gh4CL7 in drought tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bian, Z.; Jiang, S.; Wang, X.; Jiao, L.; Shao, Y.; Ma, C.; Chu, M. Comparative Genomic Analysis of COMT Family Genes in Three Vitis Species Reveals Evolutionary Relationships and Functional Divergence. Plants 2025, 14, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Xu, S.; Qu, D.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Xin, W.; Zou, D.; Zheng, H. Identification and functional analysis of the caffeic acid o-methyltransferase (COMT) gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, N.; Hisano, H.; Cao, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, W.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Fu, C. Simultaneous regulation of F5H in COMT-RNA i transgenic switchgrass alters effects of COMT suppression on syringyl lignin biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.M.; Escamilla-Trevino, L.; Yarce, J.C.S.; Kim, H.; Ralph, J.; Chen, F.; Dixon, R.A. An essential role of caffeoyl shikimate esterase in monolignol biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 2016, 86, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chao, N.; Zhang, A.; Kang, J.; Jiang, X.; Gai, Y. Systematic analysis and biochemical characterization of the caffeoyl shikimate esterase gene family in poplar. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, M.; Du, Q.; Xiao, L.; Lu, W.; Wang, L.; Xie, J.; Song, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhang, D. Genetic architecture underlying the lignin biosynthesis pathway involves noncoding RNA s and transcription factors for growth and wood properties in Populus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Luo, H.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification of the COMT Gene Family in Juglans regia L. and Response to Drought Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiao, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qin, S.; Zhang, W. Transcriptomics–proteomics analysis reveals StCOMT1 regulates drought, alkali and combined stresses in potato. Plant Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cui, H.; Li, M.; Yang, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K. Carex rigescens caffeic acid O-methyltransferase gene CrCOMT confer melatonin-mediated drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 971431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Luo, R.; Lei, C.; Zhang, M.; Gao, A.; Pu, J.; Zhang, H. Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase gene family in Mango (Mangifera indica L.) with transcriptional analysis under biotic and abiotic stresses and the role of MiCOMT1 in salt tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Chang, J.; Ma, C.; Tan, Y.-W. Single-molecule fluorescence methods to study plant hormone signal transduction pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhafizah, S.; Tan, B.C.; Sima, T.; Katharina, M.; Teo, C.H. Pandanus amaryllifolius transcriptome under drought stress reveals differential expression profile of genes related to plant hormone signal transduction and MAPK signaling pathways. Braz. J. Bot. 2025, 48, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yu, H.; Lu, S.; Bai, Y.; Meng, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, L.; Zhou, Y. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of Plant Hormone Signal Transduction Pathways in the Drought Stress Response of Hemerocallis middendorffii. Plants 2025, 14, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, C.; Ma, J.; Wu, Y.; Kang, L.; An, Q.; Zhang, J.; Deng, K.; Li, J.-Q.; Pan, C. Nanoselenium transformation and inhibition of cadmium accumulation by regulating the lignin biosynthetic pathway and plant hormone signal transduction in pepper plants. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.; Jin, Y.; Sun, H.; Xie, F.; Zhang, L. Biosynthesis and signal transduction of ABA, JA, and BRs in response to drought stress of Kentucky bluegrass. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, Y.S.; Sintaha, M.; Cheung, M.Y.; Lam, H.M. Plant Hormone Signaling Crosstalks between Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Hayat, K.; Iqbal, A.; Xie, L. Implications of abscisic acid in the drought stress tolerance of plants. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, R.; He, Y.; Ma, X.; Shen, J.; He, Z.; Lai, H. Effects of exogenous abscisic acid on the physiological and biochemical responses of Camellia oleifera seedlings under drought stress. Plants 2024, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad Aslam, M.; Waseem, M.; Jakada, B.H.; Okal, E.J.; Lei, Z.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Yuan, W.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Q. Mechanisms of abscisic acid-mediated drought stress responses in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, P.; Zhang, C.; Bi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wei, J.; Su, X.; Bai, J.; Cui, J.; Sun, C. Overexpression of Potato PYL16 Gene in Tobacco Enhances the Transgenic Plant Tolerance to Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallos-Salguero, M.S.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Fang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tao, A. Identification of AREB/ABF gene family involved in the response of ABA under salt and drought stresses in jute (Corchorus olitorius L.). Plants 2023, 12, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Wang, M.; Xiao, M.; Liu, B.; Zhou, X.; Yang, J.; Ruan, Y.; Huang, Y. Identification and function analysis of PP2C gene family shows that BnaA2.PP2C73 negatively regulates drought and salt stress responses in Brassica napus L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 214, 118568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Cao, L.; Ye, F.; Ma, C.; Liang, X.; Song, Y.; Lu, X. Identification of the maize PP2C gene family and functional studies on the role of ZmPP2C15 in drought tolerance. Plants 2024, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yuan, Z.; Wei, L.; Qiu, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Fu, J.; Cao, L.; Wang, T. Overexpression of ZmPP2C55 positively enhances tolerance to drought stress in transgenic maize plants. Plant Sci. 2022, 314, 111127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yao, X.; Liu, X.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, X. Brassinolide can improve drought tolerance of maize seedlings under drought stress: By inducing the photosynthetic performance, antioxidant capacity and ZmMYB gene expression of maize seedlings. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 2092–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helaly, M.N.; El-Hoseiny, H.M.; Elsheery, N.I.; Kalaji, H.M.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Wróbel, J.; Hassan, I.F.; Gaballah, M.S.; Abdelrhman, L.A.; Mira, A.M. 5-Aminolevulinic acid and 24-epibrassinolide improve the drought stress resilience and productivity of banana plants. Plants 2022, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naservafaei, S.; Sohrabi, Y.; Moradi, P. Effects of Exogenous Application of 24-Epibrassinolide on Photosynthesis Parameters, Grain Yield, and Protein of Dragon’s Head (Lallemantia iberica) Under Drought Stress Conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 4453–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Russinova, E. Brassinosteroid signalling. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R294–R298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.; Xu, D.; Meng-xi, H.; Yue, W.; Qi-feng, L.; Huan-huan, Y.; Jing-fu, L.; Ting-ting, Z.; Xiang-yang, X. Silencing the SLB3 transcription factor gene decreases drought stress tolerance in tomato. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Goatley, M.; Wang, K.; Conner, J.; Brown, I.; Kosiarski, K. Methyl jasmonate enhances salt stress tolerance associated with antioxidant and cytokinin alteration in perennial ryegrass. Grass Res. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Haxim, Y.; Kahar, G.; Islam, W.; Ullah, A.; Khan, K.A.; Ghramh, H.A.; Ali, S.; Asghar, M.A.; Zhao, Q. Jasmonic acid boosts physio-biochemical activities in Grewia asiatica L. under drought stress. Plants 2022, 11, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliakbari, M.; Tahmasebi, S.; Sisakht, J.N. Jasmonic acid improves barley photosynthetic efficiency through a possible regulatory module, MYC2-RcaA, under combined drought and salinity stress. Photosynth. Res. 2024, 159, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, F.; Siddiqi, E.H. Mitigation of drought-induced stress in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) via foliar application of Jasmonic acid through the augmentation of growth, physiological, and biochemical attributes. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, S.; Ullah, C.; Kortz, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Yu, P.; Gershenzon, J.; Vothknecht, U.C. Constitutive expression of JASMONATE RESISTANT 1 induces molecular changes that prime the plants to better withstand drought. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2906–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Lim, C.W.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, S.C. Pepper JAZ Protein CaJAZ1-06 Negatively Regulates Drought Stress and Abscisic Acid Signaling. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Z.; Qin, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, N.; Yao, P.; Liu, Y.; Bai, J.; Bi, Z.; Sun, C. Genome-wide analysis of the JAZ gene family in potato and functional verification of StJAZ23 under drought stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, T.; Geng, S.; Scott, P.B.; Li, H.; Chen, S. Comparative proteomics and metabolomics of JAZ7-mediated drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Proteom. 2019, 196, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J. JAZ proteins: Key regulators of plant growth and stress response. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Zhang, H.; Jin, X.T.; Niu, M.X.; Feng, C.H.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.L.; Yin, W.; Xia, X. PeFUS3 drives lateral root growth via auxin and ABA signalling under drought stress in Populus. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, P.; Zou, F.; Meng, L.; Song, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Auxin is involved in lateral root formation induced by drought stress in tobacco seedlings. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurepa, J.; Smalle, J.A. Auxin/cytokinin antagonistic control of the shoot/root growth ratio and its relevance for adaptation to drought and nutrient deficiency stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Negi, N.P.; Pareek, S.; Mudgal, G.; Kumar, D. Auxin response factors in plant adaptation to drought and salinity stress. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Retzer, K.; Vosolsobě, S.; Napier, R. Advances in understanding the mechanism of action of the auxin permease AUX1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, W.e.; Huang, D.; Pan, X. Identification of ARF genes in Juglans sigillata Dode and analysis of their expression patterns under drought stress. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. Cytokinin signaling in plant development. Development 2018, 145, dev149344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yu, H.M.; Meng, X.F.; Lin, J.S.; Li, Y.J.; Hou, B.K. Ectopic expression of glycosyltransferase UGT 76E11 increases flavonoid accumulation and enhances abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Biol. 2018, 20, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Dong, G.; Liu, C.; Ding, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ma, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Hou, B. Two pathogen-inducible UDP-glycosyltransferases, UGT73C3 and UGT73C4, catalyze the glycosylation of pinoresinol to promote plant immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, P.; Wang, T.; Zheng, C.; Hou, B. An Arabidopsis cytokinin-modifying glycosyltransferase UGT76C2 improves drought and salt tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 560696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Jia, J.; Sun, M.; Najeeb, A.; Luo, J.; Wang, X.; He, M. Single-cell transcriptomes reveal spatiotemporal heat stress response in pearl millet leaves. New Phytol. 2025, 247, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Read Number | Base Number | GC Content% | Q30 | Clean Reads | Mapped Reads | Mapped Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control-1 | 23,242,179 | 6,972,653,700 | 42.30 | 93.84 | 23,242,179 | 18,251,022 | 78.53% |

| Control-2 | 22,717,986 | 6,815,395,800 | 41.50 | 94.02 | 22,717,986 | 17,902,350 | 78.80% |

| Control-3 | 20,969,394 | 6,290,818,200 | 41.38 | 93.95 | 20,969,394 | 16,720,297 | 79.74% |

| Drought-1 | 21,683,399 | 6,505,019,700 | 42.68 | 93.79 | 21,683,399 | 16,167,757 | 74.56% |

| Drought-2 | 21,146,407 | 6,343,922,100 | 42.54 | 93.70 | 21,146,407 | 15,871,958 | 75.06% |

| Drought-3 | 22,110,927 | 6,633,278,100 | 42.69 | 93.78 | 22,110,927 | 16,713,461 | 75.59% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pei, J.; Liu, Y. Physiological Changes in and Transcriptome Responses of Asterothamnus centraliasiaticus Leaves in Response to Drought Stress. Agronomy 2026, 16, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030337

Pei J, Liu Y. Physiological Changes in and Transcriptome Responses of Asterothamnus centraliasiaticus Leaves in Response to Drought Stress. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030337

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Jiaojiao, and Ying Liu. 2026. "Physiological Changes in and Transcriptome Responses of Asterothamnus centraliasiaticus Leaves in Response to Drought Stress" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030337

APA StylePei, J., & Liu, Y. (2026). Physiological Changes in and Transcriptome Responses of Asterothamnus centraliasiaticus Leaves in Response to Drought Stress. Agronomy, 16(3), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030337