A Hybrid CNN-Transformer Model for Soil Texture Estimation from Microscopic Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

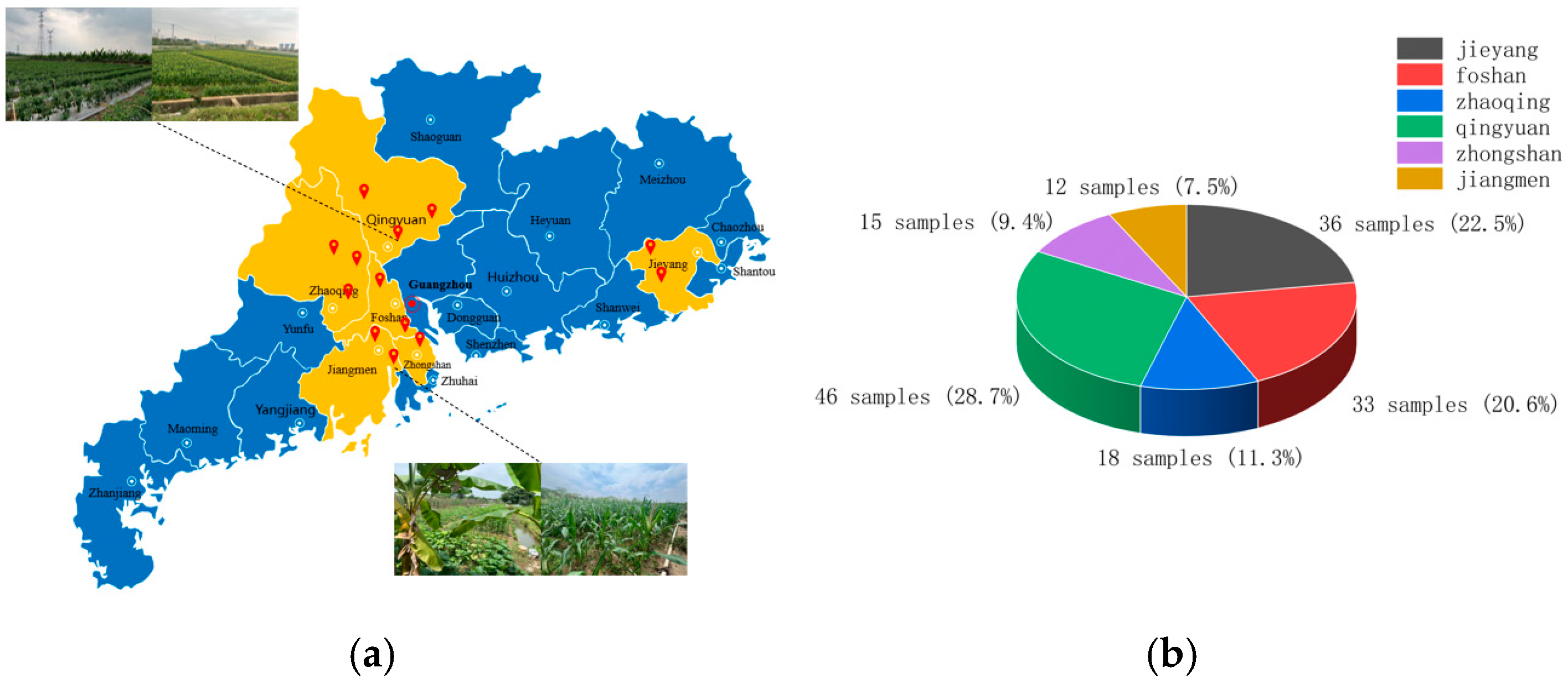

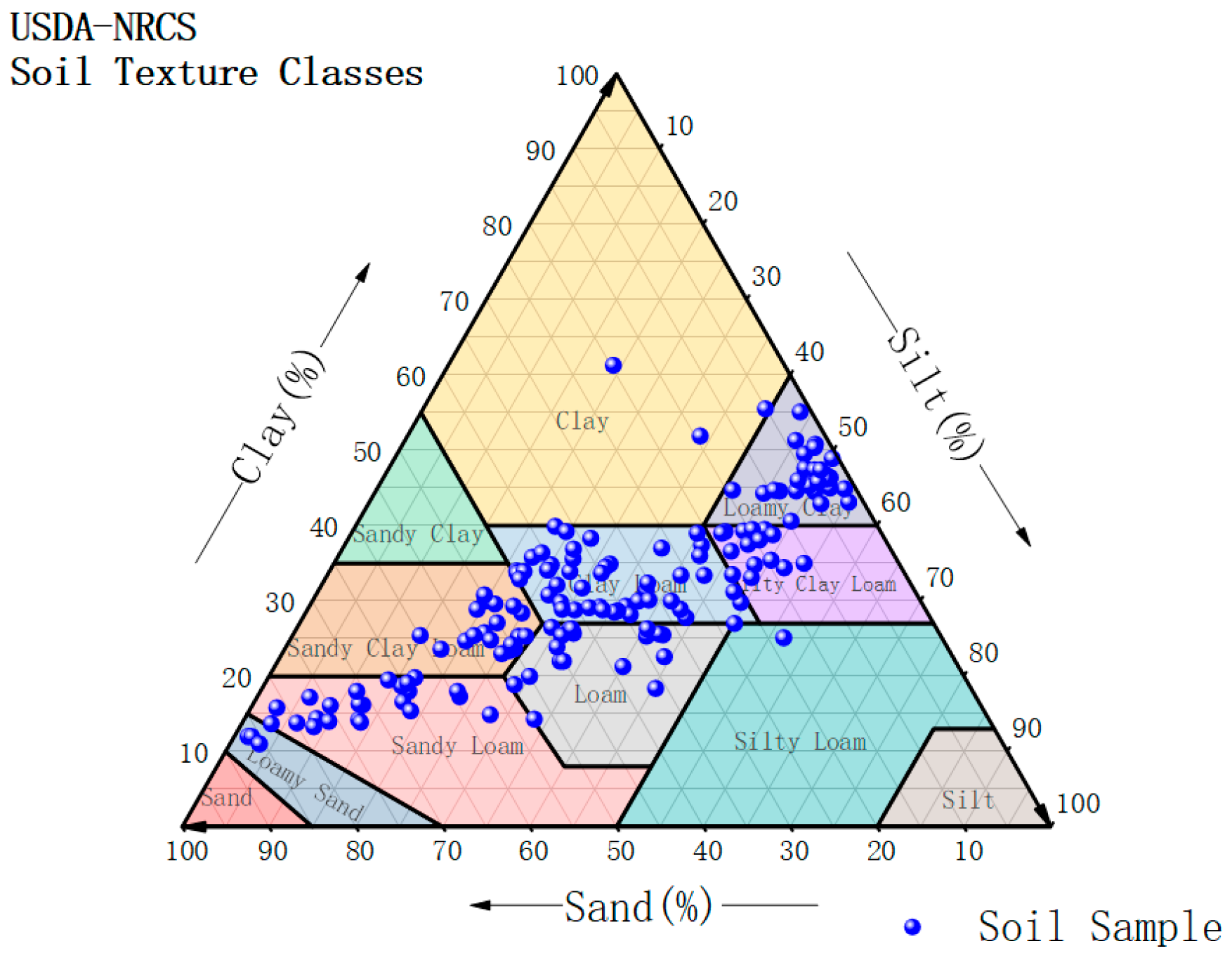

2.1. Soil Sample Collection

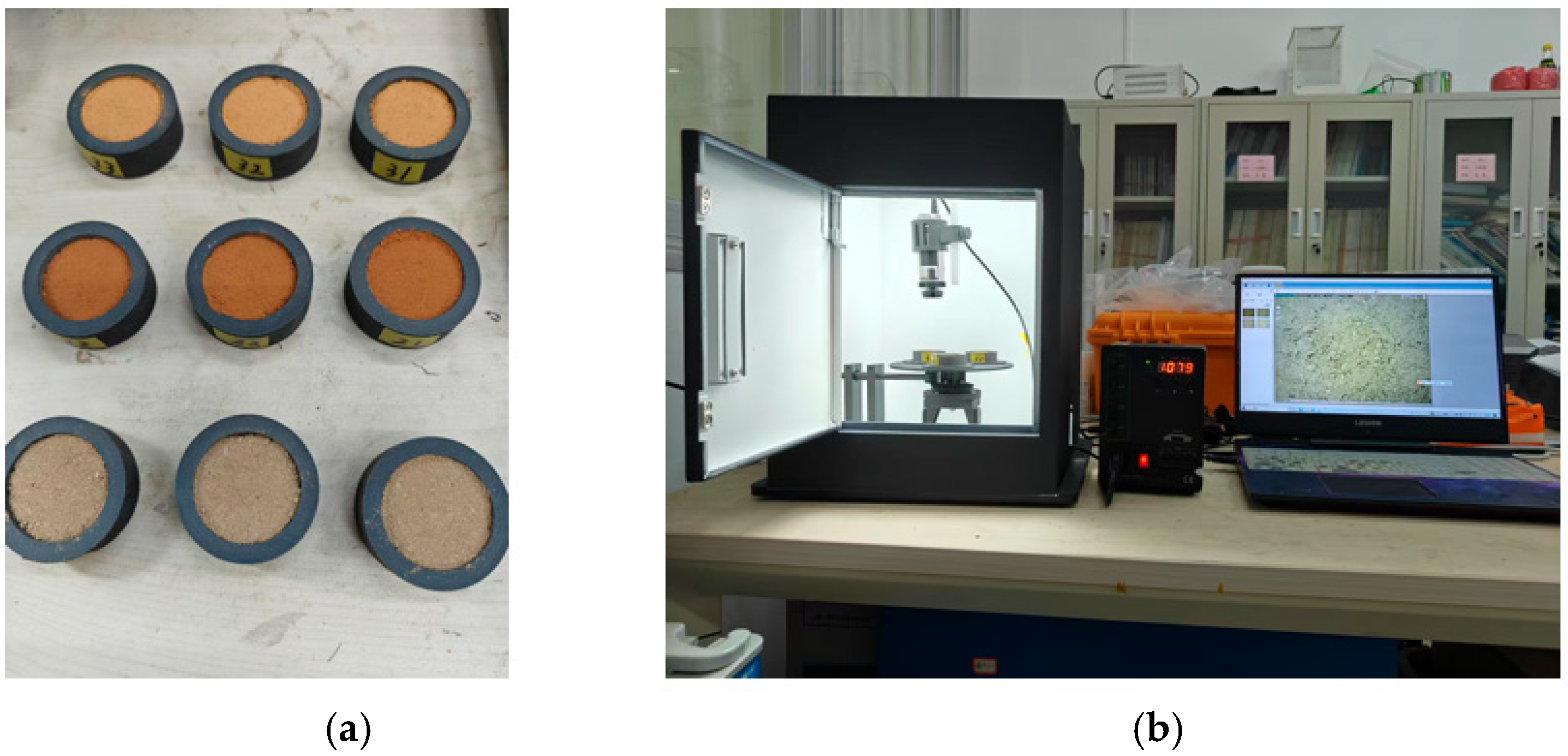

2.1.1. Image Acquisition Device Setup

2.1.2. Soil Microscopic Image Capture

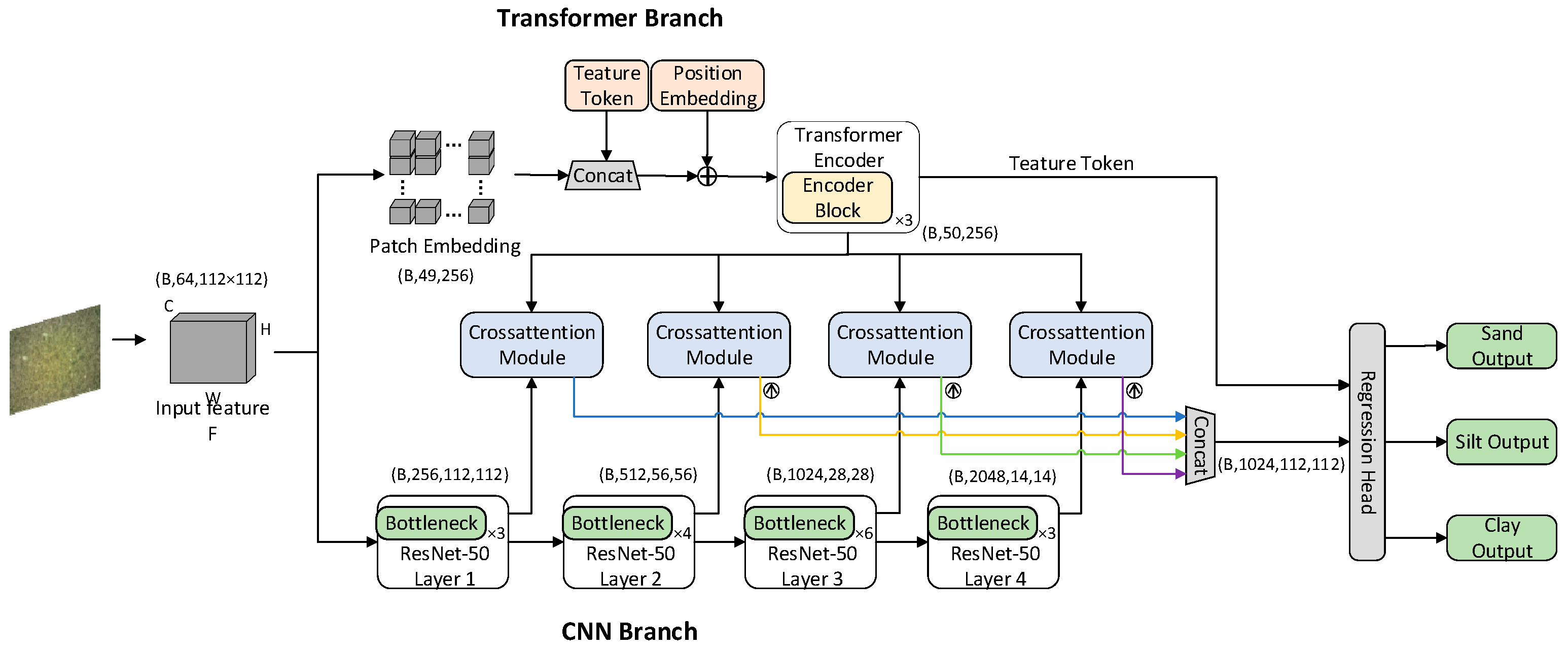

2.2. Soil Texture Detection Model Construction

2.2.1. Overall Structure of the Detection Model

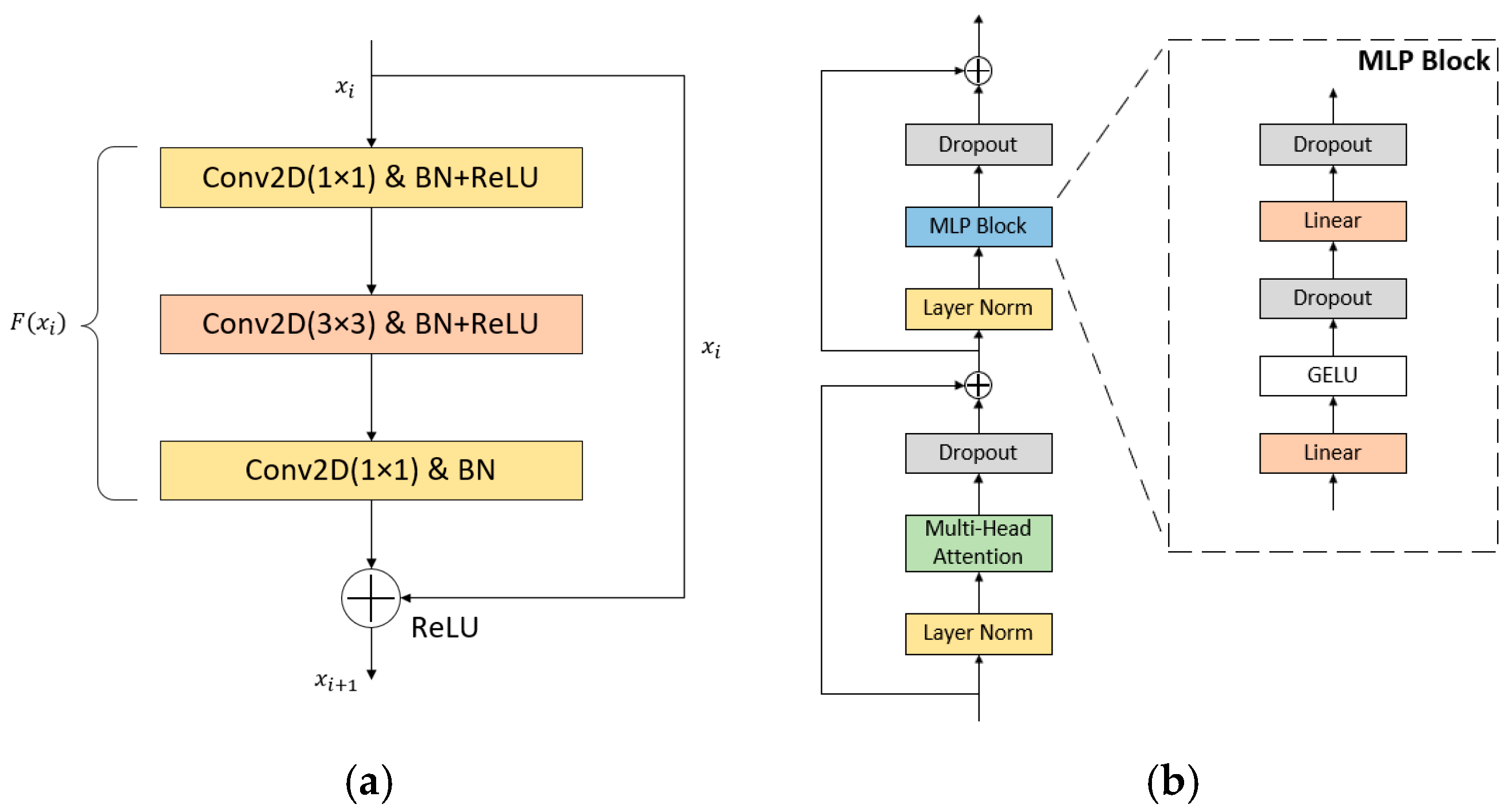

2.2.2. CNN Branch

2.2.3. Transformer Branch

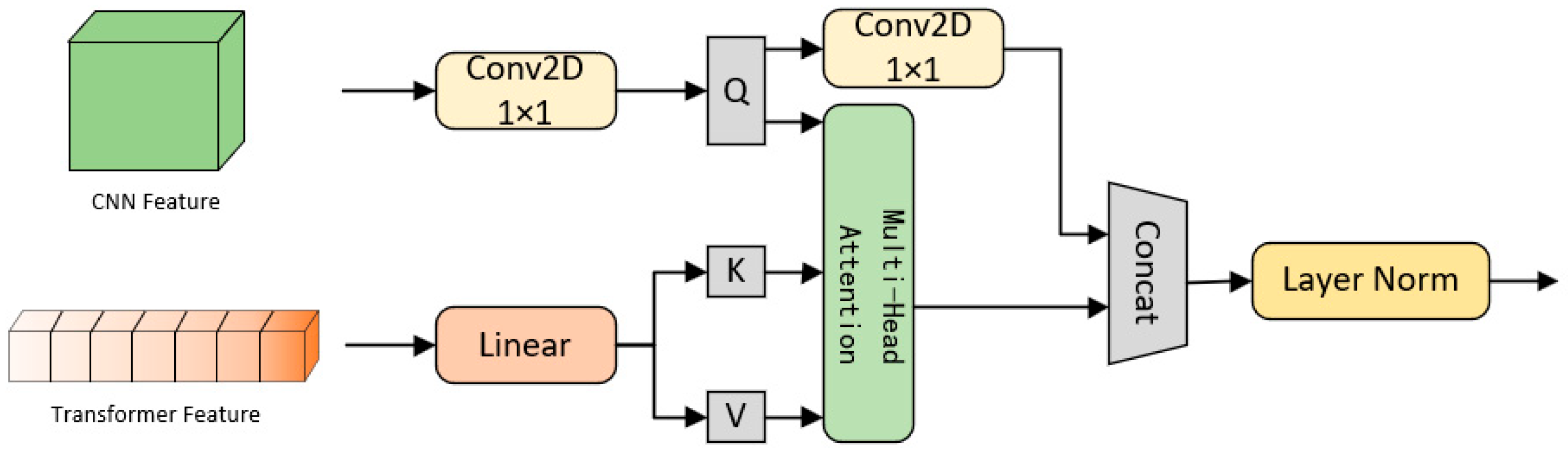

2.2.4. Cross-Attention Fusion Module

2.2.5. Output Layer

2.3. Model Evaluation Indicators

3. Results and Discussion

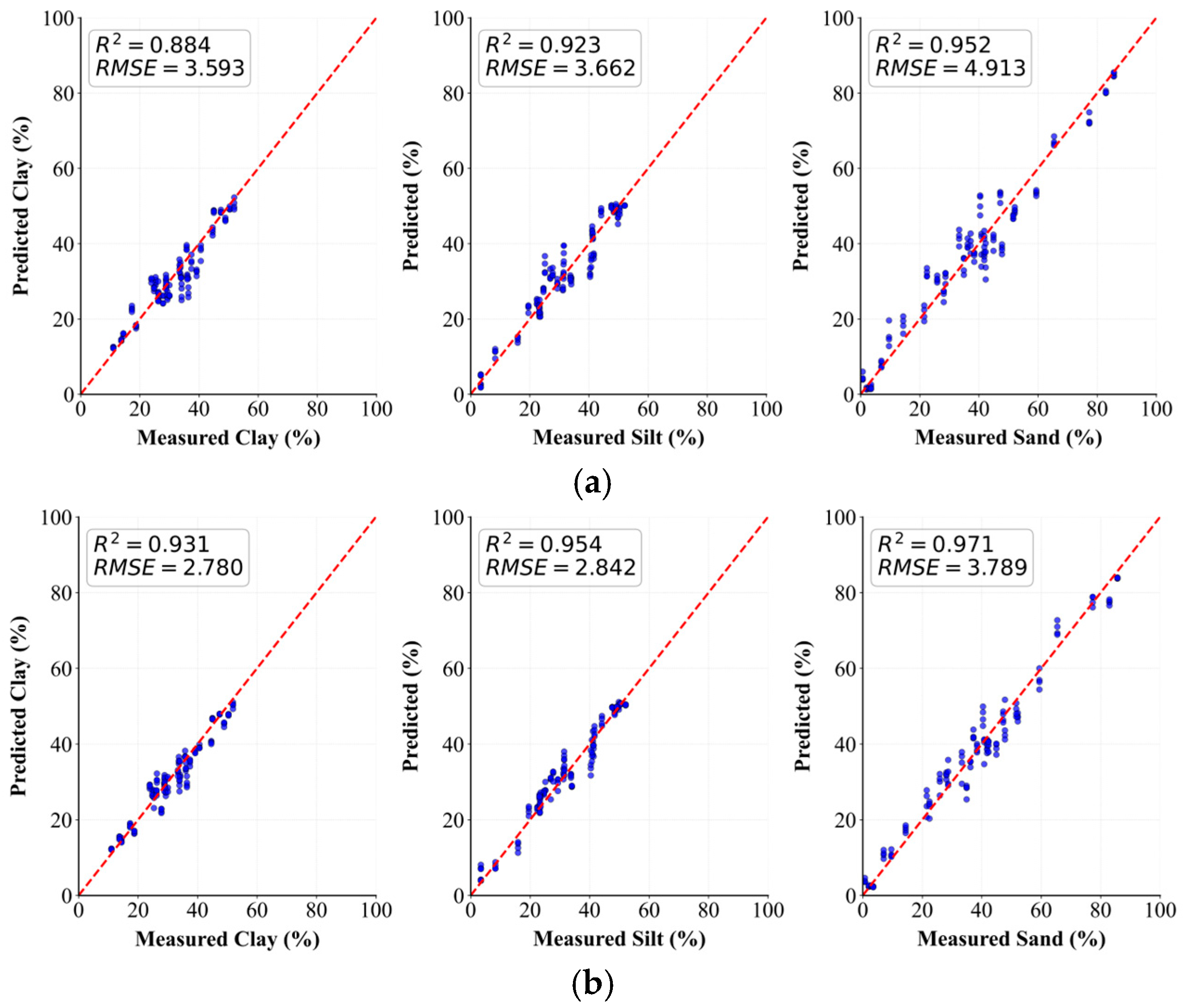

3.1. Performance Evaluation of the RVFM Model on Different Datasets

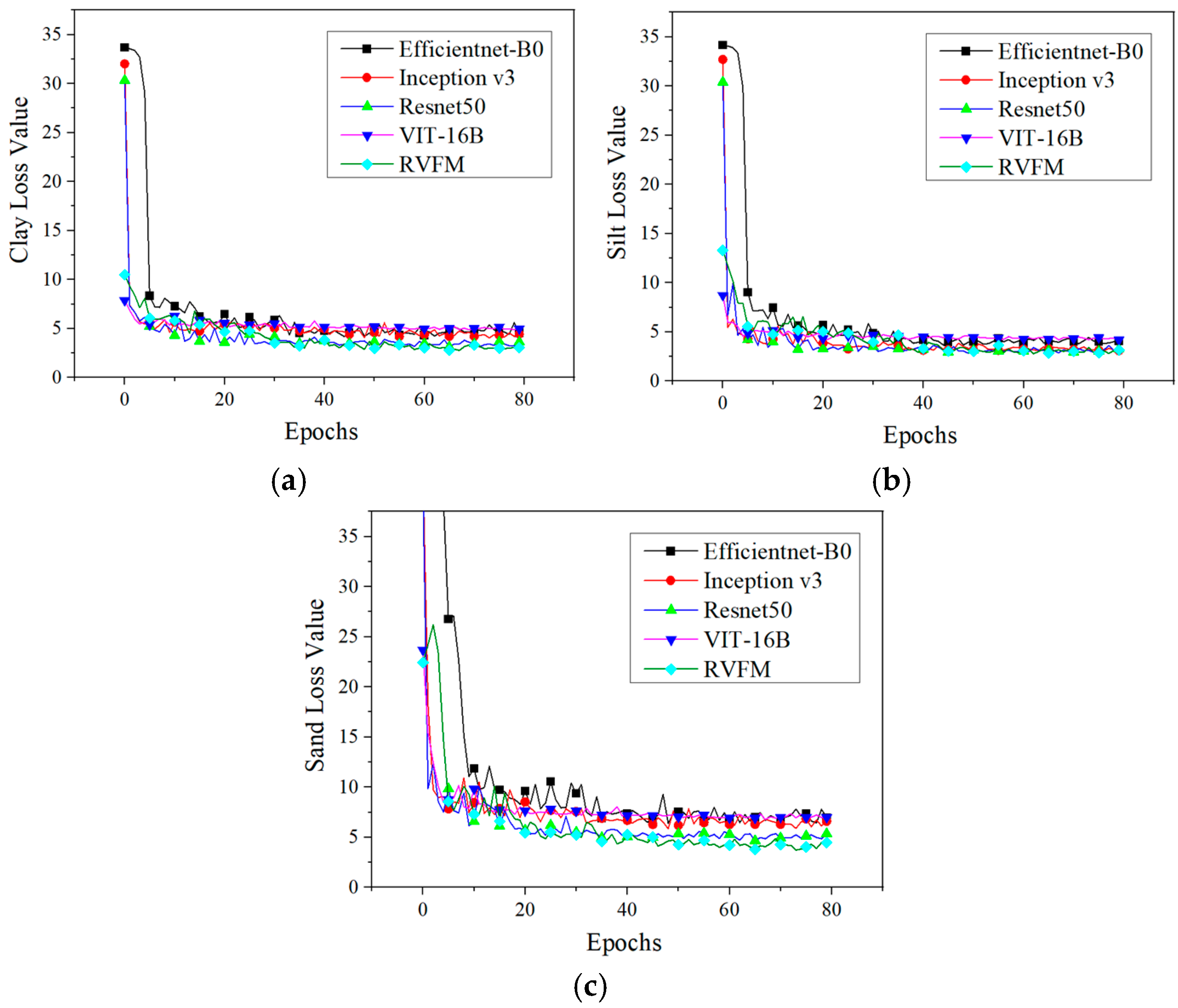

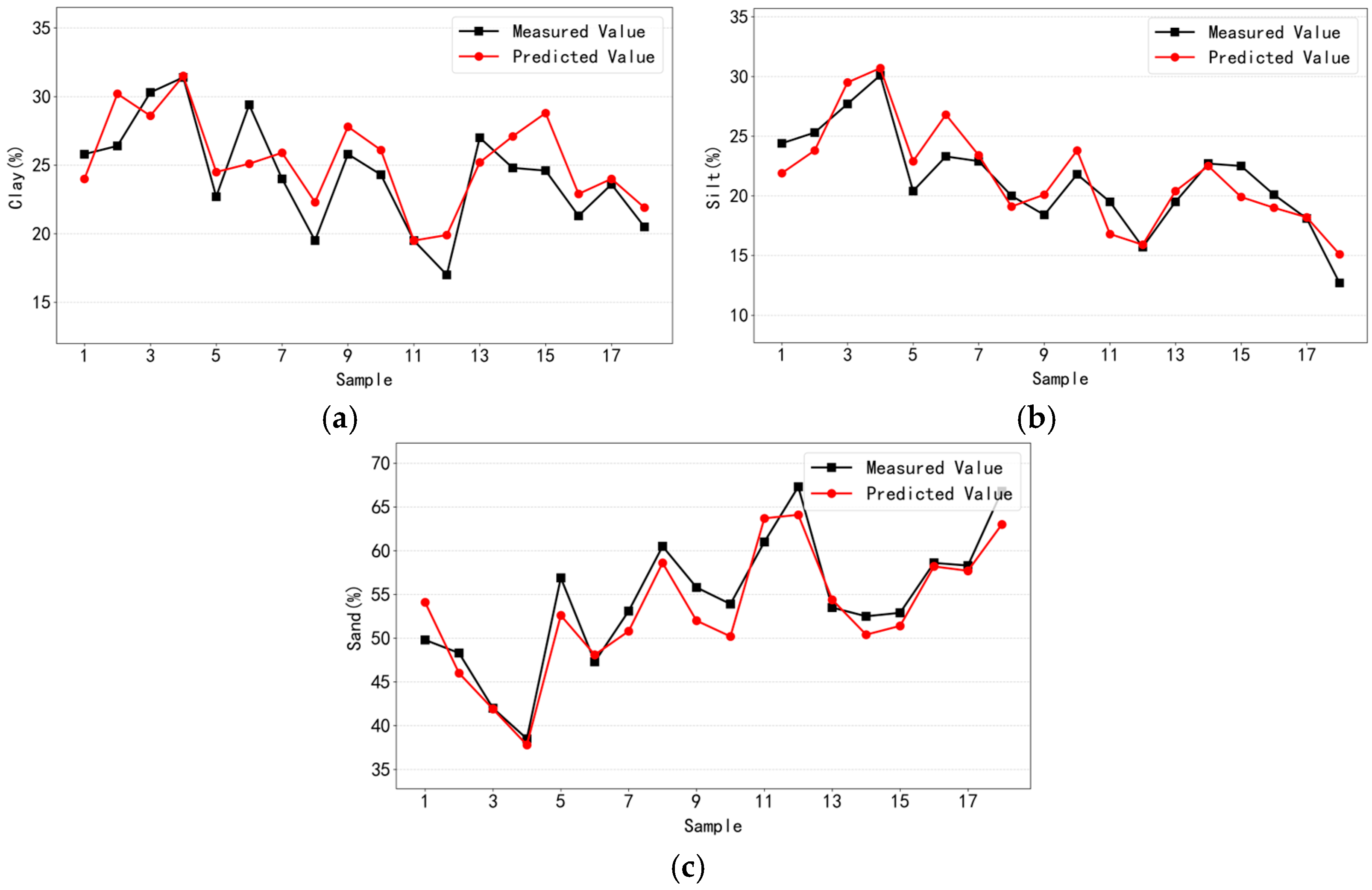

3.2. Performance Evaluation Comparison of Different Models

3.3. Ablation Experiment

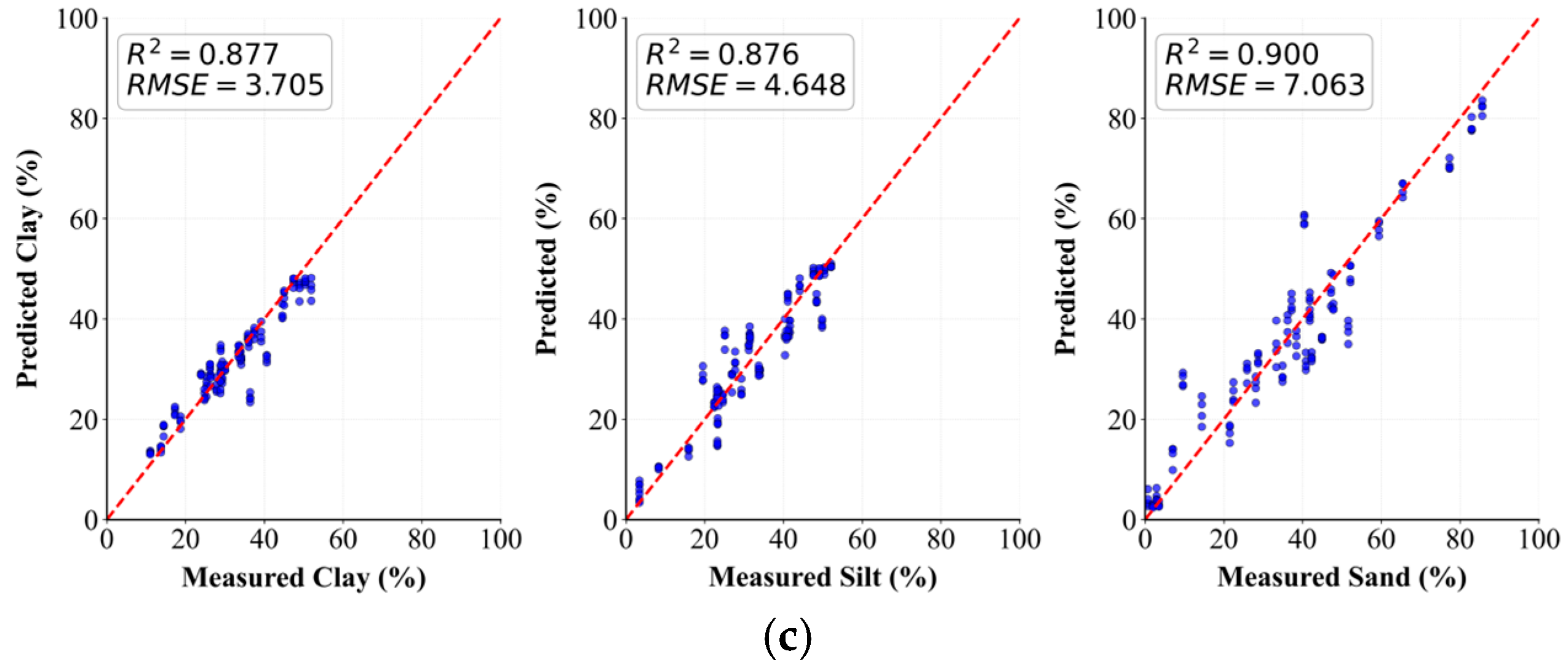

3.4. Generalisation Testing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martín, M.Á.; Pachepsky, Y.A.; García-Gutiérrez, C.; Reyes, M. On soil textural classifications and soil-texture-based estimations. Solid Earth 2018, 9, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartemink, A.E.; Minasny, B. Towards digital soil morphometrics. Geoderma 2014, 230–231, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Jiang, J.; Ouyang, L.; Yang, Q.; Du, J.; Wu, S.; Qi, L.; Hou, J.; Xing, H. Toward Flexible Soil Texture Detection by Exploiting Deep Spectrum and Texture Coding. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.N.; Zhao, R. Classification of soil texture and its application in China. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2019, 56, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.L.; Qi, Y.B.; Lu, J.L.; Peng, P.P.; Yan, Z.R.; Tang, Z.X.; Cui, K.; Zhang, K.Y. Development and Proposed Revision of the Chinese Soil Texture Classification System. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2023, 40, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, J.; Keyes, D.; Kirk, R.; Lessard, R. Standard procedure in the hydrometer method for particle size analysis. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2001, 32, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, U.; Kilinc, E.; Albayrak, F.; Aydin, A.; Torun, A. Ultrasound Penetration-Based Digital Soil Texture Analyzer. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 10751–10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faé, G.S.; Montes, F.; Bazilevskaya, E.; Añó, R.M.; Kemanian, A.R. Making Soil Particle Size Analysis by Laser Diffraction Compatible with Standard Soil Texture Determination Methods. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadporozhskaya, M.; Kovsh, N.; Paolesse, R.; Lvova, L. Recent Advances in Chemical Sensors for Soil Analysis: A Review. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocco, M.A.; Ruark, M.D.; Kucharik, C.J. Apparent electrical conductivity predicts physical properties of coarse soils. Geoderma 2019, 335, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filla, V.A.; Coelho, A.P.; Ferroni, A.D.; Bahia, A.S.R.D.; Júnior, J.M. Estimation of clay content by magnetic susceptibility in tropical soils using linear and nonlinear models. Geoderma 2021, 403, 115371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.; Silva, S.H.G.; Faria, W.M.; Poggere, G.C.; Barbosa, J.Z.; Guilherme, L.R.G.; Curi, N. Proximal sensing applied to soil texture prediction and mapping in Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 2020, 23, e00321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternikar, C.R.; Gomez, C.; Nagesh Kumar, D. Visible and infrared lab spectroscopy for soil texture classification: Analysis of entire spectra v/s reduced spectra. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 35, 101242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavão, Q.S.; Ribeiro, P.G.; Maciel, G.P.; Silva, S.H.G.; Araújo, S.R.; Fernandes, A.R.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Souza Filho, P.W.M.E.; Ramos, S.J. Texture prediction of natural soils in the Brazilian Amazon through proximal sensors. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 37, e00813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedet, L.; Faria, W.M.; Silva, S.H.G.; Mancini, M.; Dematte, J.A.M.; Guilherme, L.R.G.; Curi, N. Soil texture prediction using portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry and visible near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Geoderma 2020, 376, 114553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.; Minasny, B.; Montazerolghaem, M.; Padarian, J.; Ferguson, R.; Bailey, S.; McBratney, A.B. Convolutional neural network for simultaneous prediction of several soil properties using visible/near-infrared, mid-infrared, and their combined spectra. Geoderma 2019, 352, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Liang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F. Facing the 3rd national land survey (cultivated land quality): Soil survey application for soil texture detection based on the high-definition field soil images by using perceptual hashing algorithm (pHash). J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 3427–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, U.; Choudhury, R.D. Soil texture classification using multi class support vector machine. Inf. Process. Agric. 2020, 7, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngu, N.H.; Thanh, N.N.; Duc, T.T.; Non, D.Q.; Thuy An, N.T.; Chotpantarat, S. Active learning-based random forest algorithm used for soil texture classification mapping in Central Vietnam. Catena 2024, 234, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadnia, R.; Jahanbakhshi, A.; Rashidi, S.; Khajehzadeh, M.; Bazyar, P. Developing an automated monitoring system for fast and accurate prediction of soil texture using an image-based deep learning network and machine vision system. Measurement 2022, 190, 110669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchana, K.; Cerdà, V. Design of a portable spectrophotometric system part II: Using a digital microscope as detector. Talanta 2020, 216, 120977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, B.; Ji, W.; Biswas, A.; Adamchuk, V. Microscope-based computer vision to characterize soil texture and soil organic matter. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 152, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, B.; Ji, W.; Adamchuk, V.; Biswas, A. Characterizing soil particle sizes using wavelet analysis of microscope images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 148, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Adamchuk, V.; Huang, H.; Leclerc, M.; Jiang, Y.; Biswas, A. Proximal sensing of soil particle sizes using a microscope-based sensor and bag of visual words model. Geoderma 2019, 351, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.A.; Li, D.Q.; Wei, X.G.; Zhang, H.H. Analysis of Soil Erodibility Status and Influencing Factors in Guangdong Province. Subtrop. Soil Water Conserv. 2007, 19, 4–7+16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Pate, S.; Rathore, D.; Divyanth, L.G.; Das, A.; Nayak, A.; Dey, S.; Biswas, A.; Weindorf, D.C.; Li, B.; et al. Soil fertility prediction using combined USB-microscope based soil image, auxiliary variables, and portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Soil Adv. 2024, 2, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 60, pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Feng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, K. Hybrid model of ResNet and transformer for efficient image reconstruction of electromagnetic tomography. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2025, 102, 102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, K.; Maqsood, U.; Hussain, Q.; Majeed, S.; Kaleem, S.; Babar, M.; Qureshi, B. Soil texture analysis using controlled image processing. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, M.K.; Sharma, A.; Bajpai, V.; Subudhi, B.N.; Thangaraj, V.; Jakhetiya, V. Encoder and decoder network with ResNet-50 and global average feature pooling for local change detection. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2022, 222, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wu, J.; Ikeda, K.; Hattori, G.; Sugano, M.; Iwasawa, Y.; Matsuo, Y. Face-mask-aware Facial Expression Recognition based on Face Parsing and Vision Transformer. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2022, 164, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

- Goceri, E. An efficient network with CNN and transformer blocks for glioma grading and brain tumor classification from MRIs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 268, 126290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Jin, H.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Multi-scale vision transformer classification model with self-supervised learning and dilated convolution. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 103, 108270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Magnification | 1000 lux | 2000 lux | 3000 lux | 4000 lux |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30× |  |  |  |  |

| 40× |  |  |  |  |

| 50× |  |  |  |  |

| Data Type | Soil Particle | Min (%) | Max (%) | Mean (%) | SD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training (n = 160) | Sand | 0.7 | 86.4 | 35.5 | 22.8 |

| Silt | 1.6 | 56.7 | 33.1 | 13.9 | |

| Clay | 11.0 | 61.3 | 31.4 | 10.7 | |

| Testing (n = 32) | Sand | 0.7 | 85.6 | 36.5 | 22.7 |

| Silt | 3.4 | 52.1 | 31.5 | 13.4 | |

| Clay | 11.0 | 51.9 | 32.0 | 10.7 |

| Model | Soil Particles | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 | Sand | 0.952 | 4.875 |

| Silt | 0.949 | 2.978 | |

| Clay | 0.910 | 3.172 | |

| ViT-16B | Sand | 0.908 | 6.775 |

| Silt | 0.899 | 4.194 | |

| Clay | 0.786 | 4.889 | |

| Inception v3 | Sand | 0.931 | 5.879 |

| Silt | 0.942 | 3.191 | |

| Clay | 0.853 | 4.054 | |

| Efficientnet-B0 | Sand | 0.923 | 6.214 |

| Silt | 0.923 | 3.654 | |

| Clay | 0.850 | 4.090 | |

| RVFM | Sand | 0.971 | 3.789 |

| Silt | 0.954 | 2.842 | |

| Clay | 0.931 | 2.780 |

| Model | Soil Particles | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN Branch | Sand | 0.952 | 4.875 |

| Silt | 0.949 | 2.978 | |

| Clay | 0.910 | 3.172 | |

| CNN Branch + ViT Branch | Sand | 0.895 | 7.221 |

| Silt | 0.865 | 4.846 | |

| Clay | 0.856 | 4.007 | |

| RVFM | Sand | 0.971 | 3.789 |

| Silt | 0.954 | 2.842 | |

| Clay | 0.931 | 2.780 |

| Light Intensity | Soil Particle | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| 1000 lux | Sand | 2.746 |

| Silt | 2.389 | |

| Clay | 3.000 | |

| 2000 lux | Sand | 4.343 |

| Silt | 2.512 | |

| Clay | 3.497 | |

| 3000 lux | Sand | 3.451 |

| Silt | 2.205 | |

| Clay | 2.767 | |

| 4000 lux | Sand | 2.467 |

| Silt | 1.900 | |

| Clay | 2.409 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pan, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, Z.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, C.; Qi, L.; Wu, S. A Hybrid CNN-Transformer Model for Soil Texture Estimation from Microscopic Images. Agronomy 2026, 16, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030333

Pan M, Zhang W, Zhong Z, Jiang X, Jiang Y, Lin C, Qi L, Wu S. A Hybrid CNN-Transformer Model for Soil Texture Estimation from Microscopic Images. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030333

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Ming, Wenhao Zhang, Zeyang Zhong, Xinyu Jiang, Yu Jiang, Caixia Lin, Long Qi, and Shuanglong Wu. 2026. "A Hybrid CNN-Transformer Model for Soil Texture Estimation from Microscopic Images" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030333

APA StylePan, M., Zhang, W., Zhong, Z., Jiang, X., Jiang, Y., Lin, C., Qi, L., & Wu, S. (2026). A Hybrid CNN-Transformer Model for Soil Texture Estimation from Microscopic Images. Agronomy, 16(3), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030333