Azadirachtin and Its Nanoformulation Reshape the Maize Phyllosphere Microbiome While Maintaining Overall Microbial Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Characterization of O-cmc-aza

2.3. Preparation and Handling of Maize Leaves

2.4. Microbiome Analysis

2.5. Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Microbial Diversity on Leaf Surfaces

3.2. Microbial Abundance Analysis

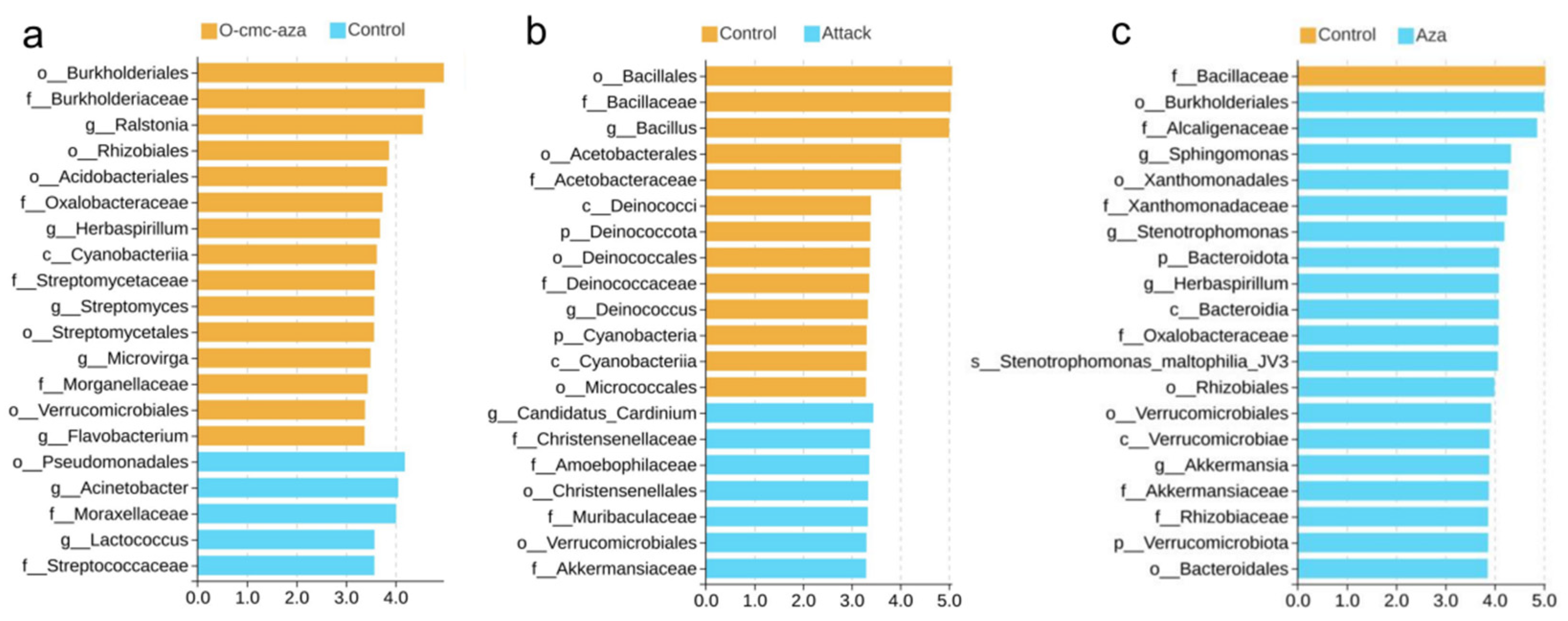

3.3. Differential Abundance Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Liu, W.; Lu, T.; Hu, B.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Lin, Z.; Qian, H. Rhizosphere Microbiome Assembly and Its Impact on Plant Growth. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 5024–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Ke, M.; Lavoie, M.; Jin, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Sun, L.; Gillings, M.; Peñuelas, J.; et al. Rhizosphere Microorganisms Can Influence the Timing of Plant Flowering. Microbiome 2018, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, N.; Li, Y.; Jin, M.; Feng, G.; Qian, H.; Lu, T. Assessment of Residual Chlorine in Soil Microbial Community Using Metagenomics. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, M.; Hildebrand, F.; Forslund, S.K.; Anderson, J.L.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Bodegom, P.M.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Anslan, S.; Coelho, L.P.; Harend, H.; et al. Structure and Function of the Global Topsoil Microbiome. Nature 2018, 560, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Xu, N.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Debognies, A.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, L.; Qian, H. Understanding the Influence of Glyphosate on the Structure and Function of Freshwater Microbial Community in a Microcosm. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, H.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, W.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Effects of S-Metolachlor on Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Seedling Root Exudates and the Rhizosphere Microbiome. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, T.; Yu, Y.; Penuelas, J.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Qian, H. Gammaproteobacteria, a Core Taxon in the Guts of Soil Fauna, Are Potential Responders to Environmental Concentrations of Soil Pollutants. Microbiome 2021, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Qu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, W.; Cui, H.; Shen, Y.; Lin, W.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Effects of Residual S-Metolachlor in Soil on the Phyllosphere Microbial Communities of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, S.; Kutschera, U. A Novel Growth-Promoting Microbe, Methylobacterium funariae Sp. Nov., Isolated from the Leaf Surface of a Common Moss. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaiss, C.A.; Zmora, N.; Levy, M.; Elinav, E. The Microbiome and Innate Immunity. Nature 2016, 535, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.H.; Harris, R.F. The Ecology and Biogeography of Microorganisms on Plant Surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2000, 38, 145–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Messier, C.; Kembel, S.W. Host Species Identity, Site and Time Drive Temperate Tree Phyllosphere Bacterial Community Structure. Microbiome 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Brettell, L.E.; Singh, B. Linking the Phyllosphere Microbiome to Plant Health. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Prasanna, R. Prospecting the Characteristics and Significance of the Phyllosphere Microbiome. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Ye, Y.; Ke, M.; Xu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Kang, J.; Yu, Y.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Effects of Chiral Herbicide Dichlorprop on Arabidopsis Thaliana Metabolic Profile and Its Implications for Microbial Communities in the Phyllosphere. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 28256–28266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Nomura, K.; Wang, X.; Sohrabi, R.; Xu, J.; Yao, L.; Paasch, B.C.; Ma, L.; Kremer, J.; Cheng, Y.; et al. A Plant Genetic Network for Preventing Dysbiosis in the Phyllosphere. Nature 2020, 580, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Ke, M.; Qu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Phyllosphere Bacterial Assemblage Is Affected by Plant Genotypes and Growth Stages. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 248, 126743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlström, C.I.; Field, C.M.; Bortfeld-Miller, M.; Müller, B.; Sunagawa, S.; Vorholt, J.A. Synthetic Microbiota Reveal Priority Effects and Keystone Strains in the Arabidopsis Phyllosphere. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knief, C.; Ramette, A.; Frances, L.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Vorholt, J.A. Site and Plant Species Are Important Determinants of the Methylobacterium Community Composition in the Plant Phyllosphere. ISME J. 2010, 4, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, K.L.; Sorensen, J.W.; Stopnisek, N.; Guittar, J.; Shade, A. Assembly and Seasonality of Core Phyllosphere Microbiota on Perennial Biofuel Crops. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardoim, P.R.; Hardoim, C.C.P.; van Overbeek, L.S.; van Elsas, J.D. Dynamics of Seed-Borne Rice Endophytes on Early Plant Growth Stages. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Monje, D.; Mousa, W.K.; Lazarovits, G.; Raizada, M.N. Impact of Swapping Soils on the Endophytic Bacterial Communities of Pre-Domesticated, Ancient and Modern Maize. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignien, L.; DeForce, E.A.; Chafee, M.E.; Eren, A.M.; Simmons, S.L. Ecological Succession and Stochastic Variation in the Assembly of Arabidopsis Thaliana Phyllosphere Communities. mBio 2014, 5, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Shen, S.-H.; Cheng, H.-P.; Jing, Y.-X.; Yanni, Y.G.; Dazzo, F.B. Ascending Migration of Endophytic Rhizobia, from Roots to Leaves, inside Rice Plants and Assessment of Benefits to Rice Growth Physiology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 7271–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.; Bodenhausen, N.; Gruissem, W.; Vorholt, J.A. The Arabidopsis Leaf Transcriptome Reveals Distinct but Also Overlapping Responses to Colonization by Phyllosphere Commensals and Pathogen Infection with Impact on Plant Health. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, A.; Jamann, T.M. Colonization and Movement of Green Fluorescent Protein-Labeled Clavibacter Nebraskensis in Maize. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1422–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Lott, A.A.; Assmann, S.M.; Chen, S. Advances and Perspectives in the Metabolomics of Stomatal Movement and the Disease Triangle. Plant Sci. 2021, 302, 110697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, M.; Ye, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, N.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, T.; Cai, Z.; Qian, H. Leaf Metabolic Influence of Glyphosate and Nanotubes on the Arabidopsis thaliana Phyllosphere. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 106, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korenblum, E.; Dong, Y.; Szymanski, J.; Panda, S.; Jozwiak, A.; Massalha, H.; Meir, S.; Rogachev, I.; Aharoni, A. Rhizosphere Microbiome Mediates Systemic Root Metabolite Exudation by Root-to-Root Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 3874–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Guo, X.; Zhai, T.; Zhang, D.; Rao, W.; Cao, F.; Guan, X. Nanobiopesticides in Sustainable Agriculture: Developments, Challenges, and Perspectives. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Lynch, I.; Guo, Z.; Xie, C.; Zhang, P. Advanced Nanopesticides: Advantage and Action Mechanisms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 203, 108051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, N.; Zhang, M.; Jia, J.; Lv, L.; Li, M. Advances in Research and Utilization of Botanical Pesticides for Agricultural Pest Management in Inner Mongolia, China. Chin. Herb. Med. 2024, 16, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.; Sun, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, S.; Salam, A.; Zhu, S.; Khan, A.H.; Holford, P.; et al. Insights into the Ameliorative Effect of ZnONPs on Arsenic Toxicity in Soybean Mediated by Hormonal Regulation, Transporter Modulation, and Stress Responsive Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1427367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.; Khan, A.H.; Salam, A.; Hu, Y.; Iqbal, A.; Hou, R.; Umar, A.W.; Wu, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z. Nano-Selenium Mitigates Arsenate Toxicity in Soybean Roots by Modulating Phenylalanine and Salicylic Acid Pathways. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Liang, X.; Cao, D.; Wu, H.; Xiao, S.; Liang, H.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Wei, H.; Peng, W.; et al. Dictamnine Suppresses the Development of Pear Ring Rot Induced by Botryosphaeria dothidea Infection by Disrupting the Chitin Biosynthesis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 195, 105534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Bu, Q.; Fan, Y.; Wang, H. High-Performance Delivery Capsules Co-Assembled from Lignin and Chitosan with Avermectin for Sustainable Pest Management. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 289, 138894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Fu, G.; Ma, S.; Tang, S.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, C. Double-Layer Nanopesticide for Duckweed Management: Employing Natural α-Terthienyl to Disrupt the Leaf Epidermal to Enhance the Efficacy of Prometryn. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, H.; Kaziem, A.E.; Miao, X.; Huang, S.; Cheng, D.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z. Effects of Exposure to Different Types of Metal–Organic Framework Nanoparticles on the Gut Microbiota and Liver Metabolism of Adult Zebrafish. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 25425–25445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Hou, R.; Wu, H.; Miao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H. Application of an Environmentally Friendly Nanopesticide Translocation System Based on Metarhizium anisopliae: Using Biodegradable Chitosan Nanopesticides to Control Spodoptera frugiperda. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310, 143261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Zhou, J.; Song, Z.; Zhang, N.; Huang, S.; Kaziem, A.E.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z. pH-Responsive λ-Cyhalothrin Nanopesticides for Effective Pest Control and Reduced Toxicity to Harmonia axyridis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 302, 120373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, M.; Yin, M.; Shen, J.; Gao, L.; Yan, S. Nano-Enabled Insecticides for Efficient Pest Management: Definition, Classification, Synergistic Mechanism, and Safety Assessment. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapeleka, J.A.; Mwema, M.F. State of Nano Pesticides Application in Smallholder Agriculture Production Systems: Human and Environmental Exposure Risk Perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabloom, E.W.; Caldeira, M.C.; Davies, K.F.; Kinkel, L.; Knops, J.M.H.; Komatsu, K.J.; MacDougall, A.S.; May, G.; Millican, M.; Moore, J.L.; et al. Globally Consistent Response of Plant Microbiome Diversity across Hosts and Continents to Soil Nutrients and Herbivores. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, P.T.; Whiteman, N.K. Insect Herbivory Reshapes a Native Leaf Microbiome. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.-H.; Yang, R.; Yang, T.; Lai, P.-L.; Chen, T.; Qiu, S.; Wang, S.; Liao, L. Improved Stabilization of Coix Seed Oil in a Nanocage-Coating Framework Based on Gliadin-Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Ca2+. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 257, 117557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Shao, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Zeeshan, M.; Zhu, S.; Liu, P.; Miao, X.; Du, P.; et al. pH-Responsive MOF Nanoparticles Equipped with Hydrophilic “Armor” Assist Fungicides in Controlling Peanut Southern Blight. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 59962–59978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Han, Z.; Tai, X.; Jin, D.; Ai, S.; Zheng, X.; Bai, Z. Maize (Zea mays L. Sp.) Varieties Significantly Influence Bacterial and Fungal Community in Bulk Soil, Rhizosphere Soil and Phyllosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchado, P.; Gil, M.I.; Moreno-Candel, M.; Allende, A. Impact of Weather Conditions, Leaf Age and Irrigation Water Disinfection on the Major Epiphytic Bacterial Genera of Baby Spinach Grown in an Open Field. Food Microbiol. 2019, 78, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dommelen, A.; Vanderleyden, J. Chapter 12—Associative Nitrogen Fixation. In Biology of the Nitrogen Cycle; Bothe, H., Ferguson, S.J., Newton, W.E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.-G.; Xiong, C.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Q.-L.; Ma, B.; Zhou, S.-Y.-D.; Tan, J.; Zhang, L.-M.; Cui, H.-L.; Duan, G.-L. Impacts of Global Change on the Phyllosphere Microbiome. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1977–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Hu, J.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hsiang, T.; Shi, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, F. Response of Microbial Communities in the Tobacco Phyllosphere under the Stress of Validamycin. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1328179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteoli, F.P.; Olivares, F.L.; Venancio, T.M.; Oliveira da Rocha, L.; Souza da Silva Irineu, L.E.; Canellas, L.P. Chapter 23—Herbaspirillum. In Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology; Amaresan, N., Senthil Kumar, M., Annapurna, K., Kumar, K., Sankaranarayanan, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 493–508. [Google Scholar]

- Ritpitakphong, U.; Falquet, L.; Vimoltust, A.; Berger, A.; Métraux, J.-P.; L’Haridon, F. The Microbiome of the Leaf Surface of Arabidopsis Protects against a Fungal Pathogen. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubatsu, L.S.; Monteiro, R.A.; de Souza, E.M.; de Oliveira, M.A.S.; Yates, M.G.; Wassem, R.; Bonatto, A.C.; Huergo, L.F.; Steffens, M.B.R.; Rigo, L.U.; et al. Nitrogen Fixation Control in Herbaspirillum Seropedicae. Plant Soil 2012, 356, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irineu, L.E.S.d.S.; Soares, C.d.P.; Soares, T.S.; Almeida, F.A.d.; Almeida-Silva, F.; Gazara, R.K.; Meneses, C.H.S.G.; Canellas, L.P.; Silveira, V.; Venancio, T.M.; et al. Multiomic Approaches Reveal Hormonal Modulation and Nitrogen Uptake and Assimilation in the Initial Growth of Maize Inoculated with Herbaspirillum Seropedicae. Plants 2023, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; He, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Kumar, A.; Xia, Z. Effects of pesticide application and plant sexual identity on leaf physiological traits and phyllosphere bacterial communities. J. Plant Ecol. 2023, 16, rtac084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wicaksono, W.A.; Berg, G.; Cernava, T. Bacterial Communities in the Plant Phyllosphere Harbour Distinct Responders to a Broad-Spectrum Pesticide. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernava, T.; Chen, X.; Krug, L.; Li, H.; Yang, M.; Berg, G. The Tea Leaf Microbiome Shows Specific Responses to Chemical Pesticides and Biocontrol Applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 667, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Liu, B.; Gao, Y.; Wei, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Hou, Z. PEG-Crosslinked O-Carboxymethyl Chitosan Films with Degradability and Antibacterial Activity for Food Packaging. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: From Diversity and Genomics to Functional Role in Environmental Remediation and Plant Growth. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutschmann, B.; Bock, M.C.E.; Jahns, S.; Neubauer, P.; Brigham, C.J.; Riedel, S.L. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis of Ralstonia Eutropha during Plant Oil Cultivations Reveals the Presence of a Fucose Salvage Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Khan, A.L.; Khan, M.A.; Imran, Q.M.; Yun, B.-W.; Lee, I.-J. Osmoprotective Functions Conferred to Soybean Plants via Inoculation with Sphingomonas Sp. LK11 and Exogenous Trehalose. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 205, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhao, K.; Liu, S.; Bao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Song, R.; Gu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Du, F. Promising Nanocarriers Endowing Non-Systemic Pesticides with Upward Translocation Ability and Microbial Community Enrichment Effects in Soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, A.-T.; Li, Y.-N.; Wu, H.; Zeeshan, M.; Zhang, Z.-X. Azadirachtin and Its Nanoformulation Reshape the Maize Phyllosphere Microbiome While Maintaining Overall Microbial Diversity. Agronomy 2026, 16, 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030334

Song A-T, Li Y-N, Wu H, Zeeshan M, Zhang Z-X. Azadirachtin and Its Nanoformulation Reshape the Maize Phyllosphere Microbiome While Maintaining Overall Microbial Diversity. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):334. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030334

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Ai-Ting, Yu-Ning Li, Hao Wu, Muhammad Zeeshan, and Zhi-Xiang Zhang. 2026. "Azadirachtin and Its Nanoformulation Reshape the Maize Phyllosphere Microbiome While Maintaining Overall Microbial Diversity" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030334

APA StyleSong, A.-T., Li, Y.-N., Wu, H., Zeeshan, M., & Zhang, Z.-X. (2026). Azadirachtin and Its Nanoformulation Reshape the Maize Phyllosphere Microbiome While Maintaining Overall Microbial Diversity. Agronomy, 16(3), 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030334