1. Introduction

Rice blast, caused by the fungus

Pyricularia oryzae, is widely recognized as one of the most destructive diseases threatening rice production worldwide and continues to pose a serious challenge to global food security. Under favorable climatic and agronomic conditions, blast outbreaks can result in severe yield losses and substantial deterioration in grain quality, particularly across major rice-growing regions in Asia. Although chemical fungicides remain an effective control measure, their long-term application is increasingly limited by environmental concerns, tightening regulatory frameworks, and the rapid emergence of fungicide-resistant pathogen populations [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As a result, the development and deployment of blast-resistant rice varieties remains the most economical and environmentally sustainable strategy for managing rice blast disease.

Over recent decades, extensive efforts have been devoted to breeding rice cultivars carrying major resistance (R) genes or quantitative resistance

loci against

P. oryzae. While these approaches have achieved notable success, resistance that relies exclusively on host genetic factors often shows limited durability in the field due to the high evolutionary potential and adaptability of the pathogen. This limitation has stimulated increasing interest in complementary resistance mechanisms that extend beyond classical host–pathogen gene-for-gene interactions. In this regard, plant-associated microbial communities have emerged as important, yet previously underappreciated, contributors to plant health and disease resistance. Microorganisms inhabiting plant tissues can suppress pathogen colonization, modulate host immune responses, and influence disease outcomes through both direct antagonistic interactions and host-mediated regulatory pathways [

5]. These observations indicate that disease resistance should be viewed not solely as a plant genetic trait, but rather as an emergent property shaped by interactions between the host and its associated microbiota.

Seeds represent a distinctive and ecologically significant microbial niche within the plant life cycle. In contrast to rhizosphere or phyllosphere microbiomes, which are strongly influenced by soil properties, climate, and management practices, seed-associated microbial communities are often vertically transmitted from parent plants to offspring and constitute the earliest microbial inoculum encountered by germinating seedlings [

6]. Many seed endophytes can persist beyond germination and influence the subsequent assembly of microbial communities in roots and aerial tissues. Because of their intimate association with reproductive tissues, seed endophytic communities are frequently more tightly linked to host genotype than environmentally acquired microbiota, suggesting that they may function as an intrinsic biological component of varietal traits.

Growing experimental evidence supports a functional role for seed-associated microbiota in plant disease resistance. Previous studies have demonstrated that bacterial seed endophytes can directly contribute to resistance against rice diseases by shaping early host physiological responses and mediating microbe–microbe interactions during initial colonization stages [

7,

8]. Compared with microbial communities that establish later in plant development, seed endophytes occupy a unique temporal and spatial position that enables them to influence early immune priming and microbial succession processes, potentially exerting long-lasting effects on disease susceptibility. Despite these advances, systematic analyses of seed endophytic bacterial communities across rice varieties with contrasting resistance to rice blast remain relatively scarce.

The Yongyou series of indica–japonica hybrid rice varieties represents one of the most widely cultivated and agronomically important hybrid systems in China. These varieties are well known for their high yield potential, broad environmental adaptability, and substantial genetic diversity. Notably, individual Yongyou varieties display pronounced differences in resistance to rice blast, even when grown under comparable environmental conditions and management regimes. This characteristic makes the Yongyou hybrid series an ideal system for investigating the association between seed endophytic bacterial communities and blast resistance while minimizing confounding environmental effects.

Beyond local-scale comparisons, it remains unclear whether resistance-associated seed endophytes exhibit consistent ecological relationships with P. oryzae across broader geographic contexts. Addressing this question is critical for evaluating the generality and potential functional relevance of microbiome-mediated resistance. Recent advances in large-scale metagenomic data mining now provide opportunities to examine such associations using publicly available sequencing datasets. By integrating local microbiome profiling with global metagenomic analyses, it becomes possible to identify large-scale co-occurrence patterns between beneficial microbial taxa and plant pathogens, thereby strengthening ecological inference beyond individual field studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site and Samples

Seed samples were collected from a rice production base located in Yinzhou District, Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China (29.73° N, 121.56° E; WGS 84). A total of 37 Yongyou hybrid rice varieties were sampled at full maturity (

Table 1). All varieties were cultivated in the same experimental field during the 2023 growing season under identical agronomic management conditions to minimize environmental variation. Based on disease-resistance evaluations provided by the National Rice Data Center, the varieties were classified into a blast-resistant group (19 varieties) and a blast-susceptible group (18 varieties) [

9].

To further reduce the influence of environmental heterogeneity on seed-associated microbial communities, all Yongyou hybrid rice varieties were grown under uniform agronomic practices, including fertilization regime, irrigation schedule, and pest control measures. This uniform field design allowed observed differences in seed endophytic bacterial communities to be primarily attributed to host genetic background rather than external environmental factors. The Yongyou hybrid series was selected because it represents a genetically related yet phenotypically diverse breeding system with well-documented variation in blast resistance, making it particularly suitable for investigating microbiome–resistance associations under controlled field conditions.

For each variety, 30 healthy and fully filled seeds were randomly selected and pooled to form one biological replicate. Pooling was performed to reduce stochastic variation among individual seeds and to obtain a representative microbial profile at the varietal level. This approach is commonly adopted in seed microbiome studies and provides sufficient biomass for downstream DNA extraction while maintaining biological relevance [

10].

2.2. Surface Sterilization

To ensure that only endophytic bacterial communities were analyzed, seeds were subjected to a strict surface-sterilization protocol. Briefly, seeds were immersed in 70% ethanol for 1 min, followed by treatment with 2% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 5 min, and then rinsed five times with sterile distilled water. All procedures were conducted in a laminar-flow hood under aseptic conditions.

Sterilization efficiency was validated by plating the final rinse water onto LB agar plates and incubating at 37 °C for 48 h. The LB agar was prepared using the following recipe: 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 10 g of NaCl, and 1 L of distilled water, with the pH adjusted to 7.0. Only samples that showed no microbial growth were used for subsequent DNA extraction. The combined use of ethanol and sodium hypochlorite has been widely validated in seed endophyte studies and effectively removes epiphytic microorganisms while preserving internal endophytic communities. This verification ensured that downstream sequencing results reflected endogenous bacterial assemblages rather than surface-associated contaminants [

11].

2.3. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from finely ground seed tissue using the MoBio PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (QIAGEN, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Three technical replicates were performed for each sample to improve extraction reliability. DNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA).

For library preparation, 1 μg of DNA per sample was fragmented to an average size of approximately 450 bp using a Covaris S220 ultrasonicator (Woburn, MA, USA). End-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, fragment purification, and PCR amplification were carried out according to standard Illumina library preparation protocols. Libraries were quantified using Qubit 3.0 fluorometry and quantitative PCR (qPCR).

The V5–V7 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 799F and 1193R, which effectively avoid co-amplification of rice chloroplast DNA [

12,

13]. DNA sequencing was performed using the Saluseq Nimbo

TM gene sequencer (Shenzhen Salus BioMed Co., Ltd., China).

2.4. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

Raw sequencing reads were processed using QIIME2 version 2024.10 [

14]. Quality filtering, denoising, and chimera removal were performed using the DADA2 plugin with a Q20 quality threshold, resulting in high-resolution amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [

15]. ASVs showing ≥97% similarity to

Oryza sativa chloroplast sequences were removed. Taxonomic assignment was conducted using a Naive Bayes classifier trained on the SILVA 138.2 reference database [

16]. ASVs not assigned to the bacterial kingdom or identified as potential contaminants were excluded from downstream analyses.

Subsequent statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.5.1. Alpha diversity indices, including Shannon diversity and Chao1 richness, were calculated to characterize within-sample diversity. Beta diversity was assessed using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, followed by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) to visualize differences in community composition. Statistical significance of community separation between blast-resistant and blast-susceptible groups was evaluated using analysis of similarities (ANOSIM). Differentially abundant bacterial genera were identified using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe), with a significance threshold of LDA score > 2.5 [

17].

2.5. Global-Scale Metagenomic Mining

To assess large-scale ecological associations between differential seed endophytes and the rice blast pathogen

Pyricularia oryzae, we employed the Logan Search platform (

https://logan-search.org, access on 20 October 2025). Logan Search enables planetary-scale screening of publicly available sequencing datasets by mapping query sequences against assembled genomic and metagenomic resources [

18]. In this study, ITS sequences specific to

P. oryzae and representative marker sequences of bacterial genera identified as differentially enriched by LEfSe were used as query probes to retrieve rice-associated metagenomic datasets from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). The ITS sequences specific to

P. oryzae were obtained from NCBI, while the representative bacterial sequences were derived from the DADA2 pipeline used for amplicon sequencing analysis in this study.

The “location count” provided by Logan Search represents the number of uniquely mapped reads assigned to a target taxon within each dataset and was used as a semi-quantitative proxy for taxon abundance. A microbe–sample abundance matrix was constructed based on location count values across all retrieved datasets. Spearman rank correlation analysis was then performed to evaluate monotonic relationships between P. oryzae abundance and that of each bacterial genus. This correlation-based approach enables robust detection of large-scale co-occurrence patterns without assuming linear relationships or uniform sequencing depth across datasets.

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of Seed Endophytic Bacterial Communities in Rice Varieties with Different Blast Resistance

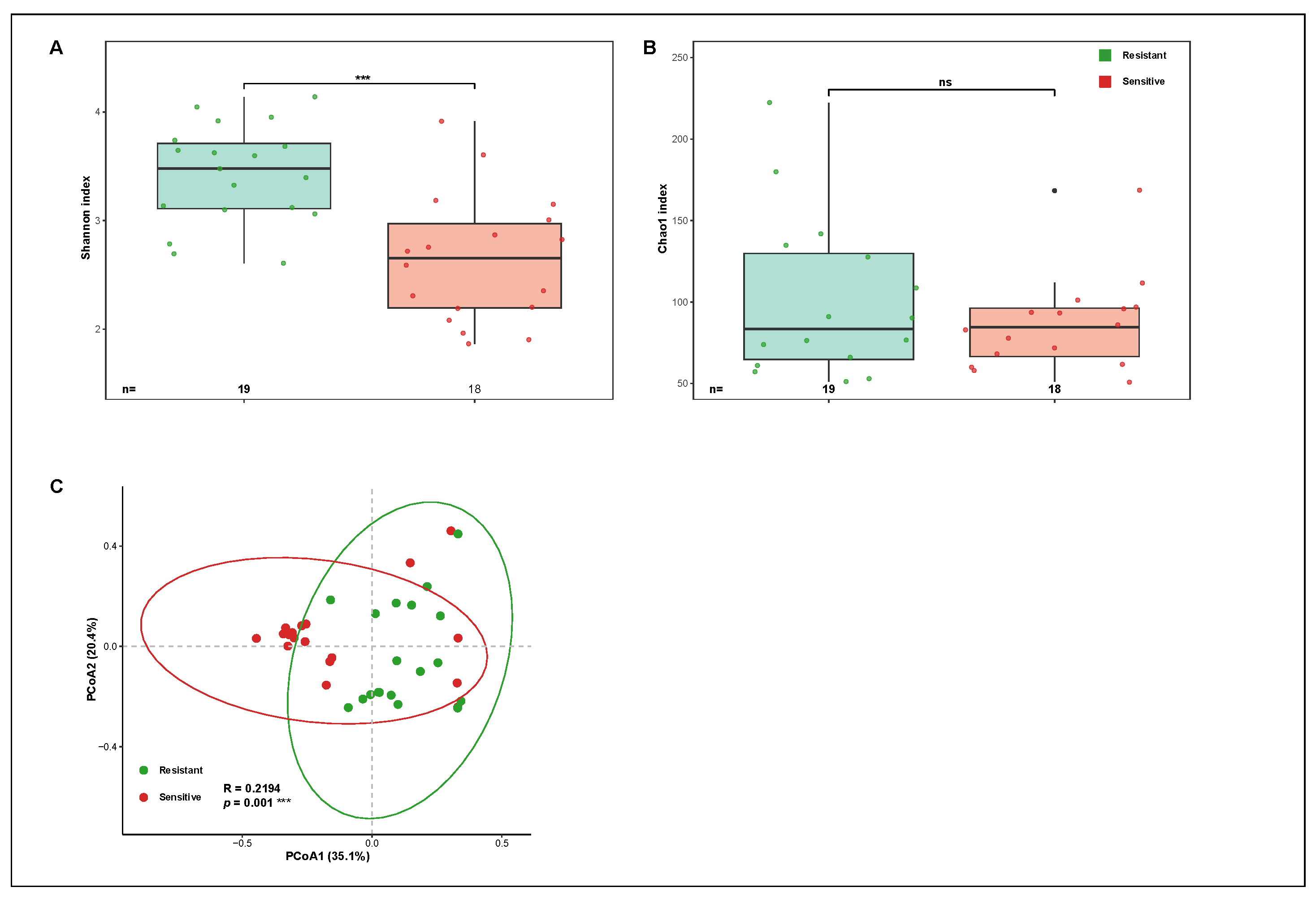

Alpha diversity analyses revealed clear differences in seed endophytic bacterial diversity between blast-resistant and blast-susceptible rice varieties (

Figure 1A,B). The Shannon diversity index was significantly higher in blast-resistant varieties than in blast-susceptible varieties (Wilcoxon rank-sum test,

p < 0.05), indicating greater community evenness and complexity in resistant seeds. In contrast, blast-susceptible varieties exhibited lower and more variable Shannon index values. Similarly, Chao1 richness estimates were consistently higher in resistant varieties, suggesting a greater number of bacterial taxa present in seeds of resistant rice varieties.

In addition to differences in median values, resistant varieties showed a narrower interquartile range for both Shannon and Chao1 indices, whereas susceptible varieties displayed greater dispersion among samples. This pattern indicates that seed endophytic communities in resistant varieties were not only more diverse but also more consistent across varieties within the resistant group.

Beta diversity analysis based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity further demonstrated distinct community composition between resistant and susceptible groups. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed a clear separation of samples along the first two axes, with resistant varieties clustering more tightly than susceptible varieties (

Figure 1C). Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) confirmed that the observed separation between the two groups was statistically significant (R > 0,

p < 0.001). Notably, samples from blast-susceptible varieties exhibited greater dispersion in ordination space, indicating higher variability in community composition compared with resistant varieties.

Together, these results demonstrate that blast-resistant rice varieties harbor seed endophytic bacterial communities characterized by higher diversity, greater richness, and more consistent community structure relative to blast-susceptible varieties.

3.2. Community Structure of Seed Endophytic Bacteria in Rice Varieties with Different Blast Resistance

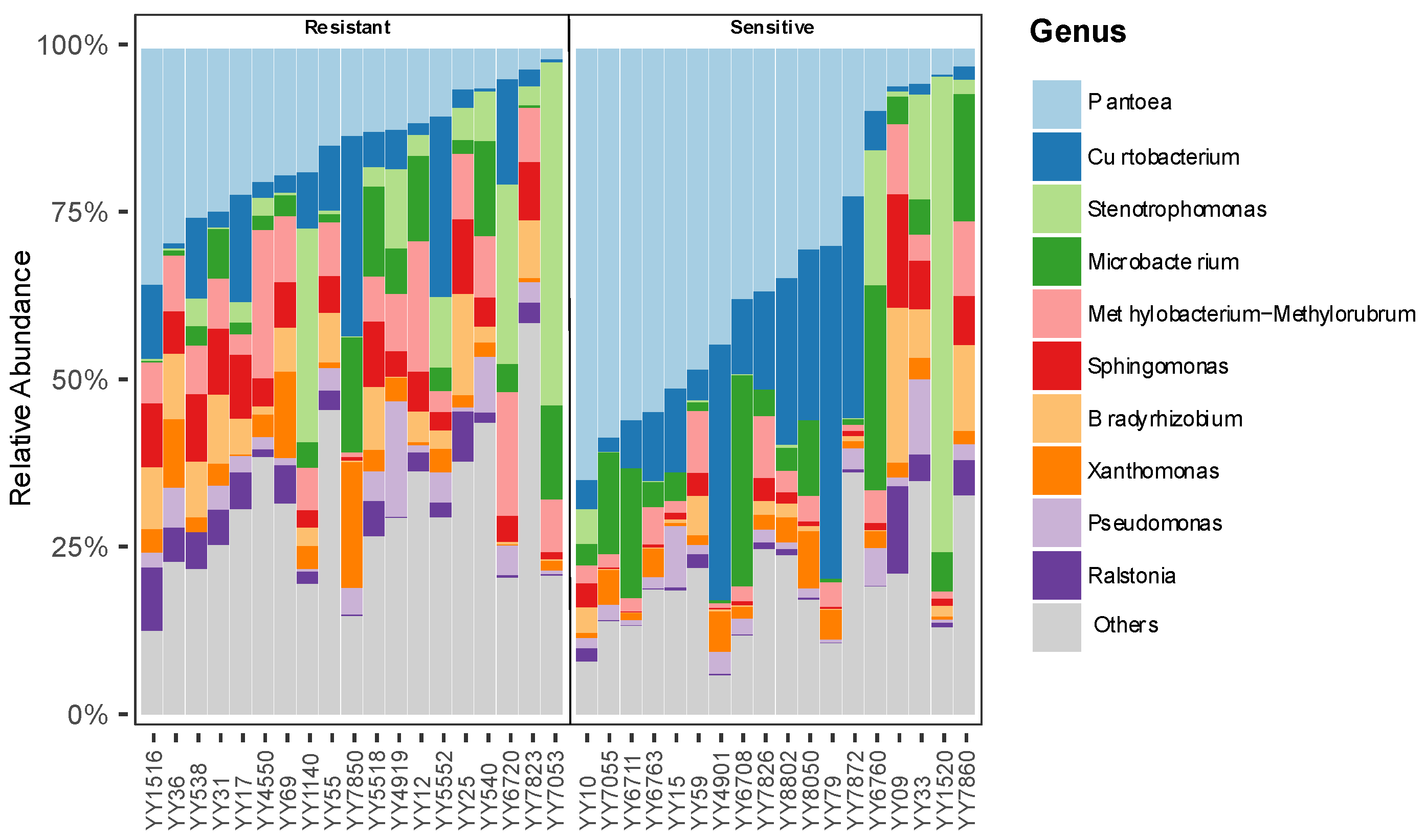

At the genus level, seed endophytic bacterial communities across all rice varieties were dominated by a limited number of taxa, with clear differences in relative abundance patterns between blast-resistant and blast-susceptible groups (

Figure 2).

Pantoea was the most abundant genus in both groups; however, its relative abundance varied substantially among susceptible varieties and was comparatively more stable in resistant varieties. In blast-susceptible varieties,

Pantoea often accounted for a larger proportion of the total community, whereas resistant varieties displayed a more even distribution among multiple dominant genera.

In contrast, several bacterial genera with known plant-associated functions, including Stenotrophomonas, Sphingomonas, Bradyrhizobium, and Methylobacterium–Methylorubrum, exhibited consistently higher relative abundances in blast-resistant varieties. These genera collectively contributed a greater proportion of the total bacterial community in resistant seeds, whereas their representation in susceptible varieties was reduced and more variable across samples.

Conversely, blast-susceptible varieties showed an increased relative abundance of several taxa with reported opportunistic or potentially pathogenic lifestyles. Notably, Curtobacterium was extensively enriched in susceptible varieties but occurred at markedly lower relative abundance in resistant varieties.

Importantly, the observed differences between resistant and susceptible varieties were driven primarily by shifts in relative abundance rather than the complete presence or absence of specific taxa. Most dominant genera were detected in both groups; however, resistant varieties exhibited a more balanced community structure with multiple co-dominant taxa, while susceptible varieties were often characterized by the dominance of one or two genera. These results indicate that blast resistance is associated with a reorganization of seed endophytic bacterial communities rather than the recruitment of entirely distinct microbial assemblages.

3.3. Differentially Enriched Endophytic Genera Identified by LEfSe Analysis

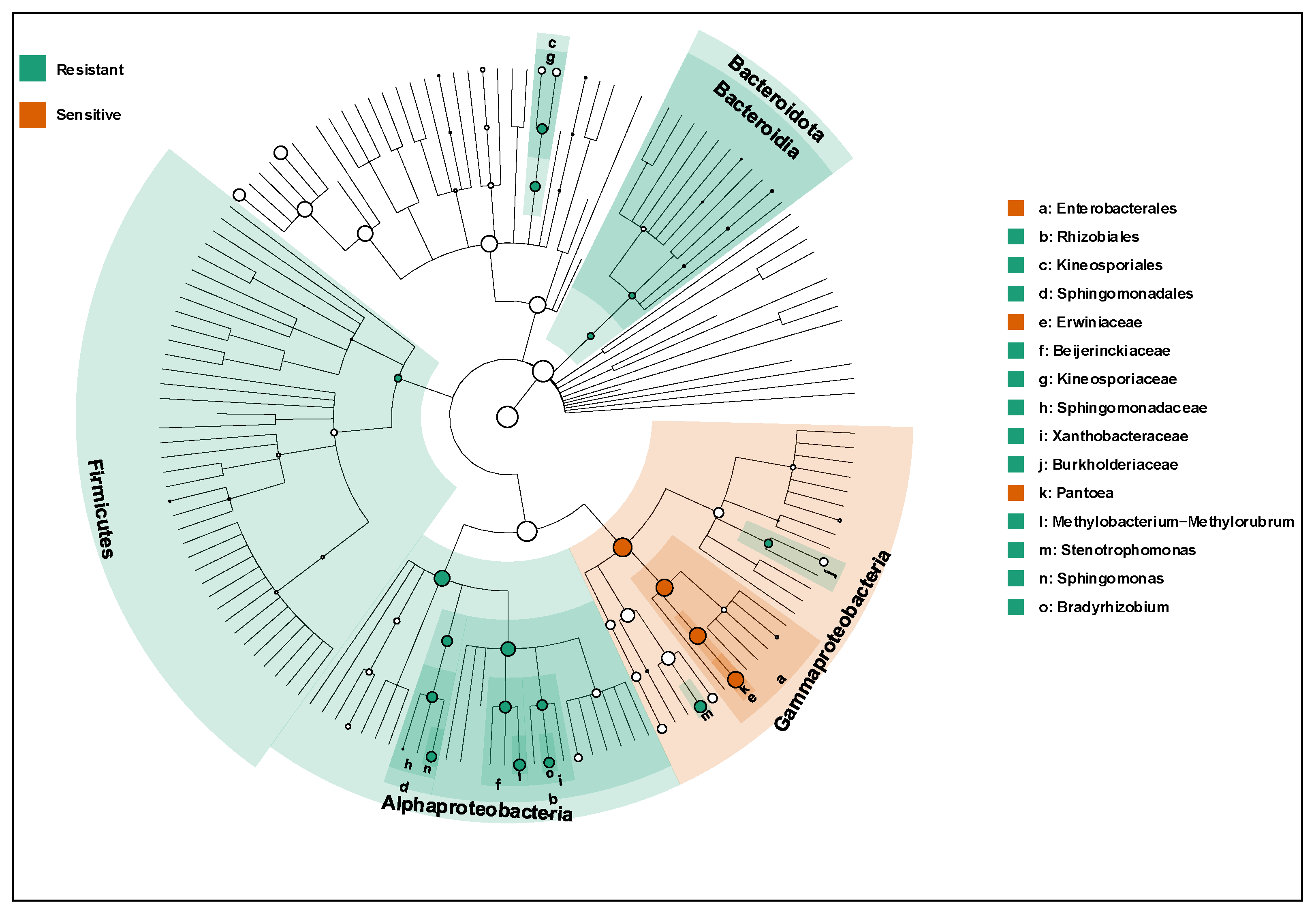

To identify bacterial taxa associated with blast resistance status, linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was applied to compare seed endophytic communities between resistant and susceptible rice varieties. LEfSe analysis identified a greater number of bacterial genera significantly enriched in blast-resistant varieties than in blast-susceptible varieties (

Figure 3).

In blast-resistant varieties, several genera exhibited high LDA scores (LDA > 3.0), including Stenotrophomonas, Sphingomonas, Bradyrhizobium, and Methylobacterium–Methylorubrum, indicating strong discriminatory power between resistance groups. These taxa were consistently enriched across resistant varieties, highlighting their potential as microbial biomarkers associated with blast resistance.

In contrast, fewer genera were significantly enriched in blast-susceptible varieties, and these taxa generally exhibited lower LDA scores. Some genera enriched in susceptible varieties were detected sporadically and showed higher variability among samples. The imbalance in both the number and effect size of discriminatory taxa between the two groups suggests that blast-resistant varieties are characterized by a more distinct and stable set of seed-associated bacterial biomarkers.

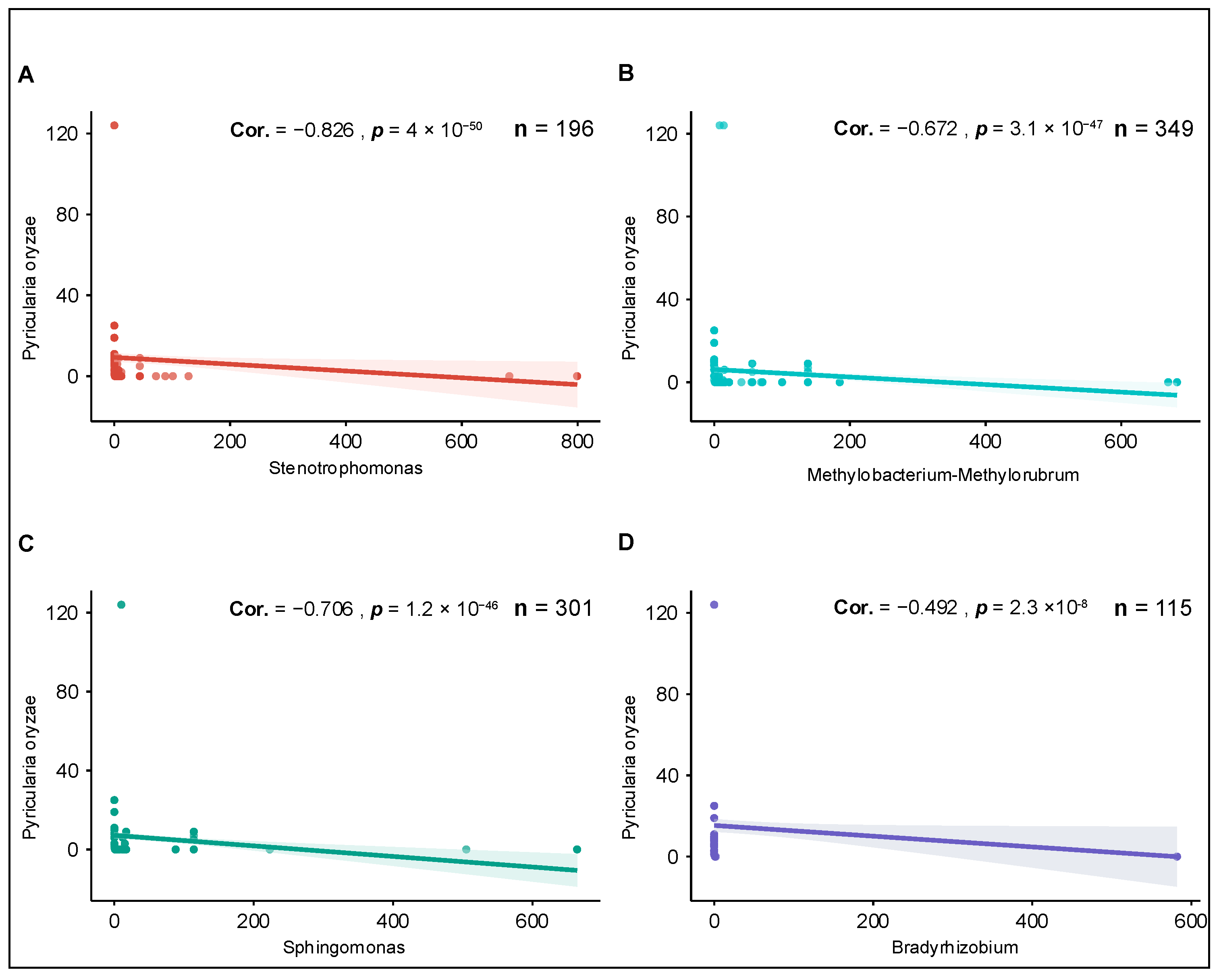

3.4. Global Ecological Correlations Between Endophytic Bacterial Genera and Rice Blast Pathogen in Resistant Varieties

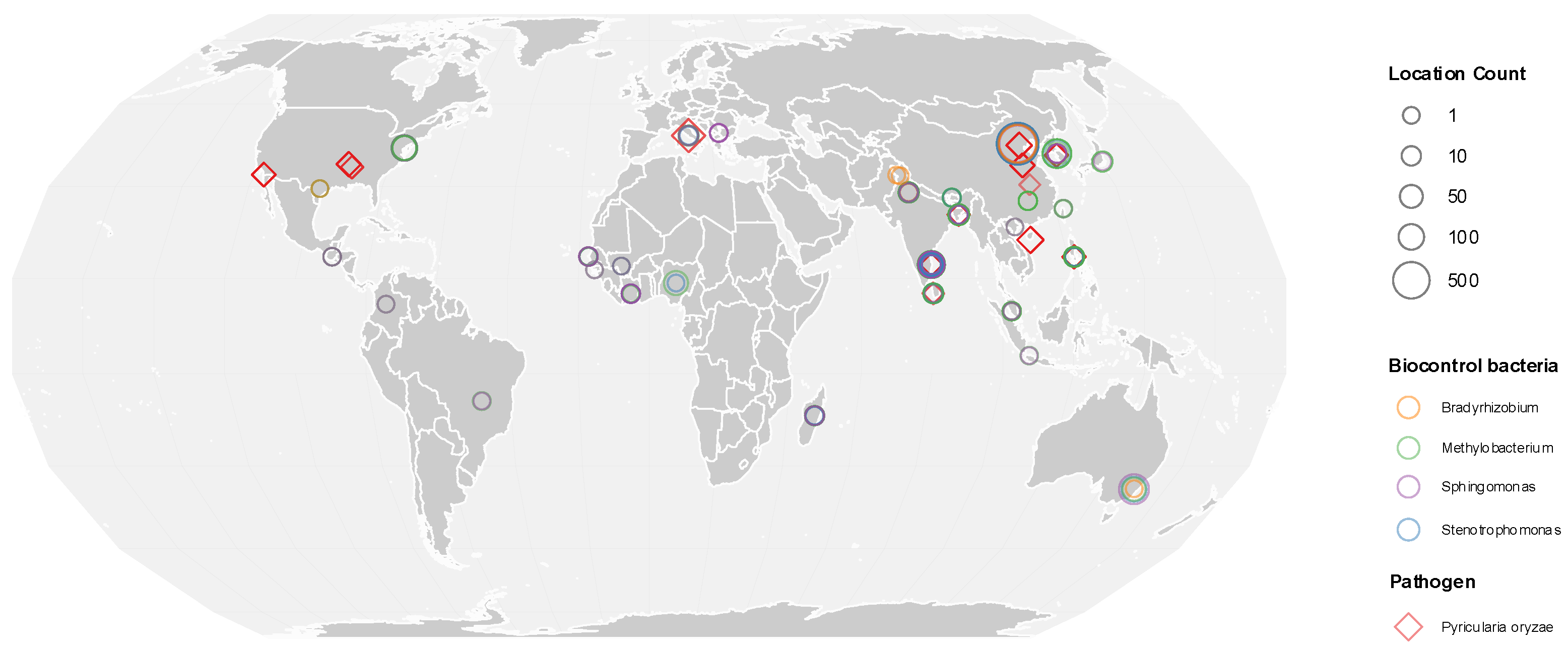

To evaluate whether bacterial taxa enriched in blast-resistant varieties exhibited consistent ecological associations with the rice blast pathogen beyond the local field scale, it was analyzed global rice-associated metagenomic datasets using the Logan Search platform. For each dataset, the presence and relative abundance of

P. oryzae and resistance-associated bacterial genera were mapped to the same geographic coordinates, allowing direct visualization of their spatial co-occurrence across sampling locations. Spearman correlation analysis revealed significant negative associations between the abundance of

P. oryzae and multiple bacterial genera identified as enriched in resistant varieties (

Figure 4).

Among these taxa,

Stenotrophomonas and

Sphingomonas displayed the strongest negative correlations with

P. oryzae abundance (Spearman |ρ| > 0.7,

p < 0.01), indicating a pronounced inverse relationship across diverse geographic regions (

Figure 5).

Methylobacterium–

Methylorubrum also showed a significant negative correlation, although with slightly lower correlation coefficients. In contrast,

Bradyrhizobium exhibited a moderate but statistically significant negative association with

P. oryzae, suggesting a weaker yet consistent global pattern.

The direction of correlation between P. oryzae and these bacterial genera was consistent across the majority of analyzed datasets, despite substantial heterogeneity in sequencing depth and sample origin. This consistency indicates that bacterial taxa enriched in blast-resistant rice seeds tend to be associated with reduced pathogen abundance at a global scale, reinforcing the robustness of the observed associations.

4. Discussion

From a mechanistic perspective, the pronounced differentiation of seed endophytic bacterial communities between blast-resistant and blast-susceptible rice varieties observed in this study suggests that seed-associated microbiota may participate in disease resistance through multiple, partially overlapping pathways. Unlike rhizosphere or phyllosphere microbiomes, which are continuously reshaped by soil properties, climate, and agronomic management, seed endophytes colonize plant tissues at the earliest developmental stages and therefore possess a clear temporal advantage [

19,

20]. Upon germination, these vertically or pseudo-vertically transmitted bacteria can rapidly establish within emerging roots and shoots, occupying ecological niches that might otherwise be accessible to opportunistic or pathogenic microorganisms [

21]. Such priority effects are increasingly recognized as critical determinants of microbiome assembly and stability, and may exert long-lasting influences on host–microbe and microbe–microbe interactions throughout plant development.

For foliar pathogens such as

Pyricularia oryzae, which typically infect aboveground tissues at later developmental stages, early microbial establishment may influence disease outcomes indirectly. Microbial communities that become established during seedling growth could shape subsequent immune responsiveness, nutrient allocation, and microbial recruitment in aerial tissues, thereby altering the ecological context in which pathogen invasion occurs. Although direct movement of seed endophytes to leaf tissues cannot be assumed, their effects on early host physiology may propagate across developmental stages, contributing to systemic resistance phenotypes [

22].

One plausible mechanism underlying the association between seed endophytes and blast resistance is immune priming. Increasing evidence indicates that plant-associated microbiota can enhance host resistance by modulating basal defense pathways, metabolic fluxes, and signaling networks, rather than acting solely through direct antagonism of pathogens. In rice, microbiome-mediated regulation of host metabolism has been shown to contribute to resistance against multiple diseases, underscoring the importance of host physiological modulation as a component of microbe-assisted defense [

23]. Phytohormone signaling represents a particularly important interface linking microbial activity and plant immunity. Antagonistic or synergistic interactions among auxin, cytokinin, salicylic acid, and jasmonate pathways have been implicated in plant–pathogen interactions, suggesting that microbial regulation of hormonal balance may indirectly influence disease susceptibility or resistance [

24]. Within this framework, resistance-associated seed endophytes may function as persistent immune modulators that prime the host for subsequent pathogen challenge, rather than providing immediate pathogen suppression.

In parallel with host-mediated mechanisms, direct antagonistic interactions between seed endophytes and pathogens are also likely to contribute to blast suppression. Several bacterial genera enriched in seeds of blast-resistant varieties possess well-documented antifungal or competitive traits. Members of the genus

Stenotrophomonas are ecologically versatile and capable of colonizing diverse plant-associated environments, and some strains are known to produce antifungal metabolites that inhibit filamentous fungi [

25]. Likewise,

Sphingomonas species are recognized for their ability to produce extracellular polysaccharides and form stable biofilms, traits that promote persistence within plant tissues and facilitate competitive exclusion of invading microorganisms [

26]. Through niche occupation, competition for limiting resources, and modification of the local microenvironment, these bacteria may constrain the ability of

P. oryzae to complete key stages of its infection cycle. This interference could be particularly effective given that multiple metabolic and developmental pathways—such as amino acid biosynthesis, redox homeostasis, and secondary metabolite production—are indispensable for infection-related morphogenesis and pathogenicity in

P. oryzae [

27,

28].

Seed-associated microbial communities should therefore not be viewed as static assemblages, but rather as dynamic populations that influence, and are influenced by, early plant development. Vertically transmitted or seed-inherited endophytes have been identified as core components of rice microbiomes across generations, reinforcing their close association with host genotype and reproductive tissues [

29]. Compared with environmentally acquired microbiota, seed-associated communities may represent a more stable and host-linked microbial component, potentially subject to indirect selection during breeding. The consistent enrichment of specific bacterial taxa in seeds of blast-resistant varieties observed here is consistent with the hypothesis that seed microbiomes may act as heritable or semi-heritable contributors to disease resistance [

30].

Beyond the influence of individual taxa, community-level properties such as diversity, stability, and functional redundancy are increasingly recognized as key determinants of disease suppression. Disease-suppressive microbiomes often emerge from complex microbial interactions rather than the activity of single dominant species [

31]. Ecological theory predicts that higher microbial diversity can enhance resistance to biological invasion by pathogens through niche saturation, resource partitioning, and functional overlap [

32]. The higher diversity and more balanced community structure observed in seeds of blast-resistant varieties may therefore confer resistance through emergent community properties, rather than through isolated antagonistic effects.

Several bacterial genera identified in this study have previously been reported to exhibit plant-associated functional traits, although their roles are highly context dependent. For example,

Pantoea is widely distributed in rice seeds and includes strains with plant growth-promoting and endophytic characteristics, while certain species may display pathogenic potential under specific environmental or host conditions [

33,

34,

35]. The significant differences in

Pantoea abundance between resistant and susceptible varieties observed here suggest that host genotype or microbial community context may determine whether this genus exerts beneficial or detrimental effects. This context dependency highlights the importance of interpreting microbiome–disease relationships at the community level rather than focusing exclusively on individual taxa [

36]. Also,

Curtobacterium was extensively enriched in seeds of susceptible varieties but occurred at much lower relative abundance in resistant varieties. Although

Curtobacterium is not a primary rice blast pathogen, multiple species within this genus have been associated with plant diseases, vascular colonization, or tissue damage in diverse crops [

37]. The enrichment of

Curtobacterium may therefore reflect a dysbiotic seed microbiome state in susceptible varieties, in which early microbial colonization favors opportunistic taxa that could compromise host basal defense, disrupt microbial community balance, or facilitate subsequent pathogen invasion [

38]. From this perspective, resistance-associated seed microbiomes may be shaped not only by the enrichment of beneficial endophytes but also by the suppression or exclusion of potentially deleterious bacteria. This dual role highlights the importance of considering both protective and risk-associated microbial taxa when interpreting microbiome–disease relationships.

The enrichment of nitrogen- and hormone-associated genera such as

Methylobacterium–Methylorubrum further suggests an indirect metabolic contribution to disease resistance. Members of this group are known to influence plant growth, phytohormone metabolism, and stress tolerance, which may enhance host vigor and resilience to pathogen invasion [

39,

40]. Because nutrient availability and hormonal balance are tightly coupled to plant immune responses, microbial regulation of these processes may influence disease outcomes even in the absence of direct pathogen antagonism.

At a broader ecological scale, integrating local seed microbiome profiling with large-scale metagenomic analyses allows evaluation of whether resistance-associated bacteria exhibit consistent relationships with pathogens across diverse environments. Recent advances in large-scale data mining and microbiome research emphasize the importance of identifying conserved microbial–pathogen associations that extend beyond individual field studies [

41]. The negative associations observed between

P. oryzae and several bacterial genera across global rice-associated datasets lend additional support to the ecological relevance of seed endophytes identified in this study, although such correlations do not by themselves establish causality.

From an applied perspective, these findings have important implications for sustainable rice blast management. Seed endophytic microbiota represent a vertically transmitted and potentially stable microbial resource that could be leveraged through microbiome-informed breeding, targeted seed treatments, or controlled microbial inoculation strategies. Such approaches may complement traditional genetic resistance and chemical control, contributing to more durable and environmentally friendly disease management strategies. Nevertheless, experimental validation at the strain level and under controlled infection conditions will be essential to disentangle direct antagonistic effects from host-mediated mechanisms and to translate ecological associations into practical applications. Overall, this study highlights seed-associated microbial communities as an underappreciated yet functionally relevant component of rice blast resistance and provides a conceptual framework for future mechanistic and translational research.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that rice varieties differing in blast resistance harbor seed endophytic bacterial communities that are distinct not only in overall diversity but also in community structure and taxonomic composition. Blast-resistant rice varieties were characterized by higher bacterial diversity, a more even distribution of dominant taxa, and the consistent enrichment of multiple genera with documented plant-associated functions, including nutrient cycling, immune modulation, and antagonistic interactions with pathogens. In contrast, blast-susceptible varieties often exhibited less balanced community structures, with the dominance of a limited number of taxa, including genera potentially associated with opportunistic or dysbiotic states. Importantly, these differences were driven primarily by shifts in relative abundance and ecological organization rather than by the exclusive presence or absence of specific taxa, suggesting a reconfiguration of seed microbiome assembly associated with host resistance phenotypes. These results indicate that seed-associated microbiota may represent an additional, microbiome-mediated layer of blast resistance that complements host genetic traits.

By integrating local seed microbiome profiling with global-scale metagenomic evidence, it was further demonstrated that several beneficial seed-associated bacterial genera exhibit stable negative associations with the rice blast pathogen P. oryzae across diverse rice-associated environments. This convergence of local and macroecological patterns highlights the potential ecological relevance of seed-inherited microbiota in shaping pathogen prevalence.

Overall, these emphasize seed-associated microbial communities as a previously underappreciated component of rice blast resistance. Incorporating seed microbiome information into rice breeding, varietal assessment, and disease management strategies may provide new opportunities to complement conventional genetic resistance and chemical control approaches.