Identification Pathogenicity Distribution and Chemical Control of Rhizoctonia solani Causing Soybean Root Rot in Northeast China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Pathogenicity Assessment of the Pathogenic Fungi

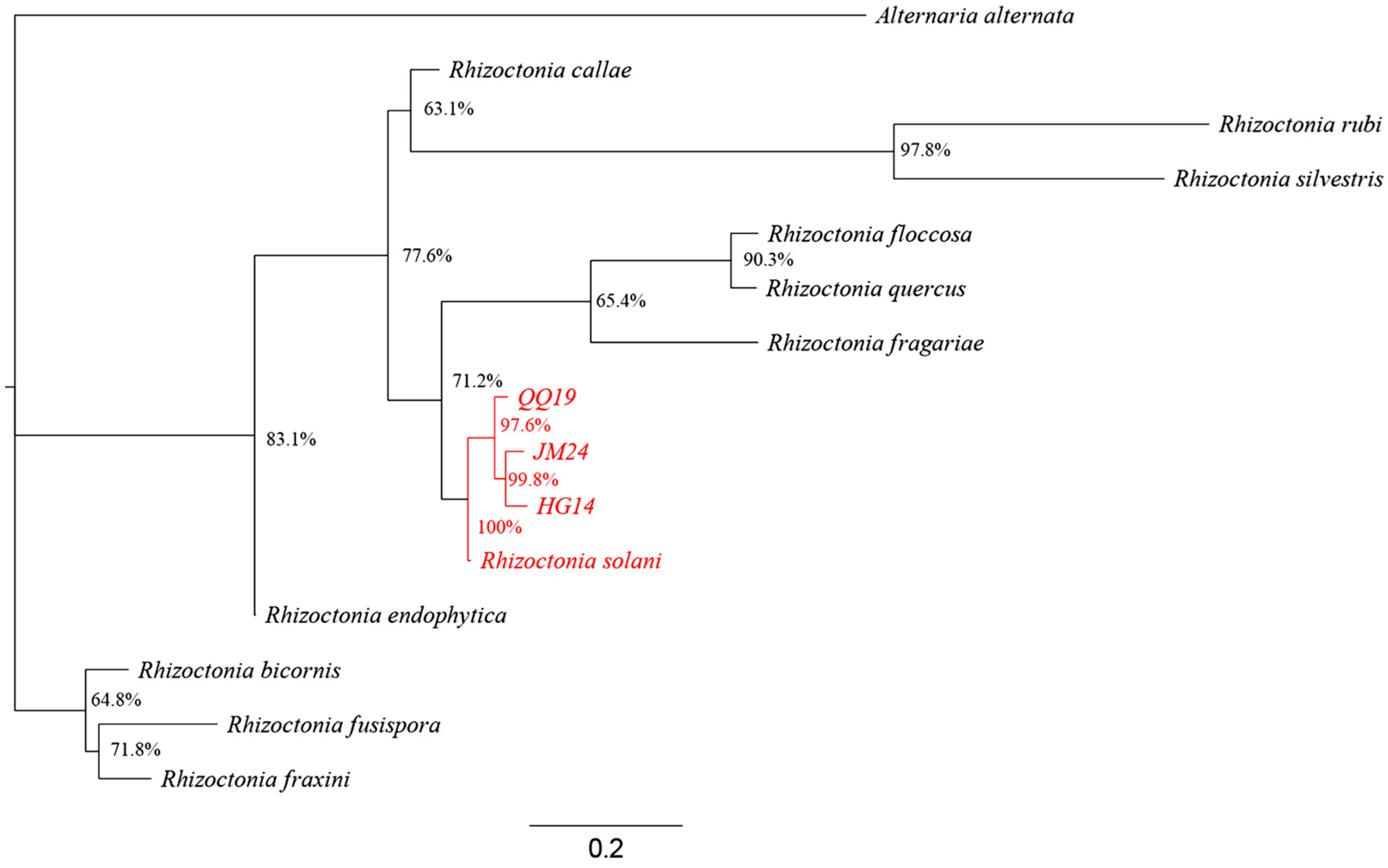

2.2. Morpho-Molecular Identification of Pathogenic Fungi

2.3. Pathogenicity Assay

2.4. Evaluation of Fungicide Sensitivity

2.5. Pot Assay for Control Efficacy of Soybean Root Rot

| Disease Index = [(Number of diseased seedlings in each grade × Corresponding grade value)/(Total seedlings investigated × Highest grade value)] × 100 |

| Control Efficacy (%) = [(DI of inoculated control − DI of treatment)/DI of inoculated control] × 100% |

3. Results

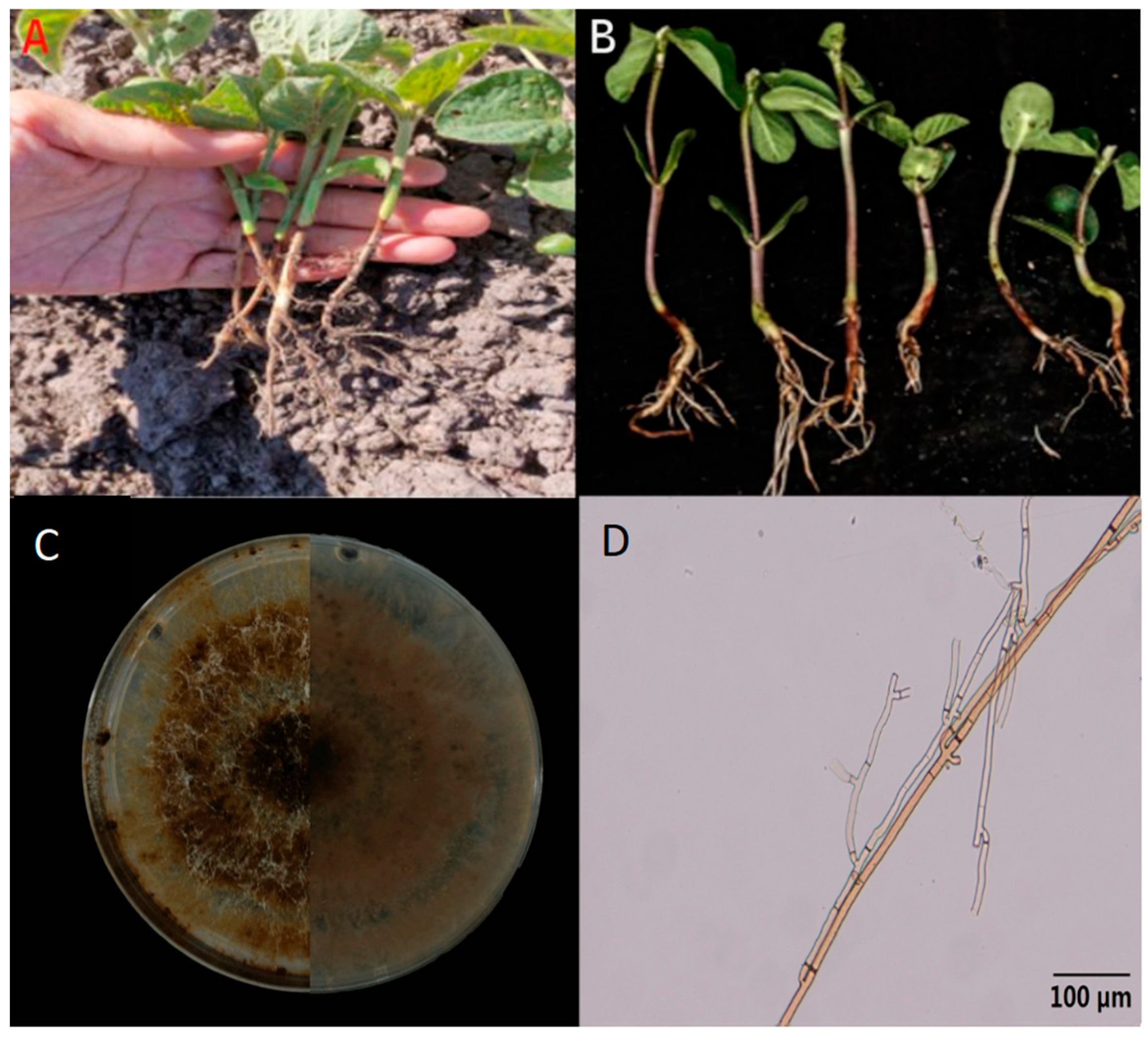

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of Soybean Root Rot Pathogens

3.2. Pathogenicity Assay Results

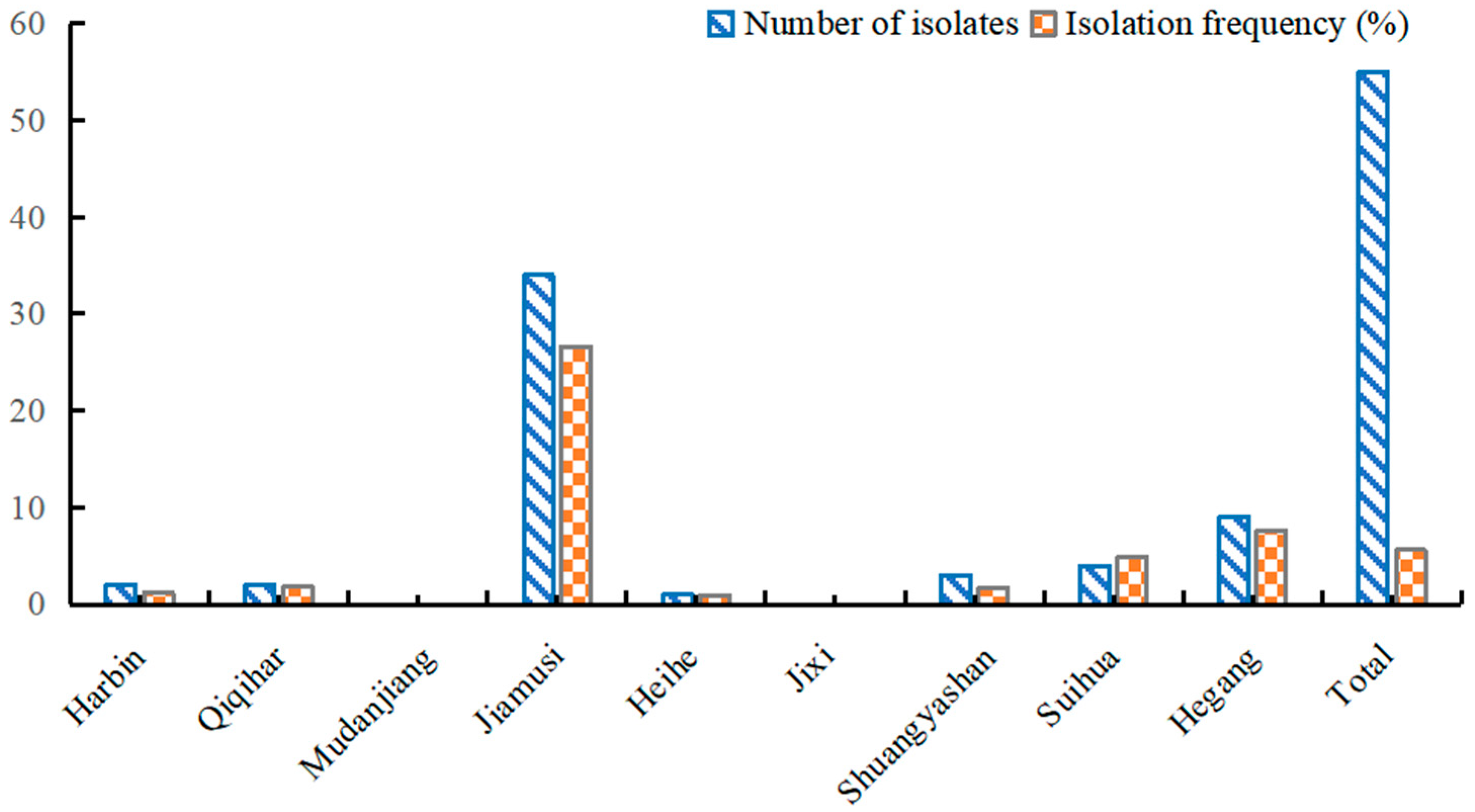

3.3. Distribution and Pathogen Isolation Percentage of Rhizoctonia solani from Soybean Root Rot in Heilongjiang Province

3.4. Sensitivity of Rhizoctonia solani Isolates to Fungicides

3.5. Control Efficacy of Seed-Coating Fungicides

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartman, G.L.; West, E.D.; Herman, T.K. Crops that feed the World 2. Soybean—Worldwide production, use, and constraints caused by pathogens and pests. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Wei, M.; Khan, N.; Liang, J.; Han, D.; Zhang, H. Assessing sustainable future of import-independent domestic soybean production in China: Policy implications and projections for 2030. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1387609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, N.W.; Chen, X.; Lu, X.C.; Yan, J.; Han, X.Z.; Zhu, Y.C.; Zou, W.X. Effects of soil management strategies on maize and soybean yields in northeast China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.J.; Wu, Y.K.; Yu, J.D.; Ma, L.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, B.X.; Ren, H.L. Current Situation and Technical Requirements of Soybean Production in Saline-Alkali Areas in Western Heilongjiang Province. Heilongjiang Agric. Sci. 2023, 10, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Xiao, C.H.; Ma, J.Z.; Yu, M.; Li, Y.M.; Wang, G.L.; Zhang, L.P. Prokaryotic diversity in continuous cropping and rotational cropping soybean soil. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 298, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.X.; Yao, X.D.; Zhang, P.Y.; Liu, W.B.; Huang, J.X.; Sun, H.X.; Wang, N.; Zhang, X.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, H.J.; et al. Effects of Continuous Cropping on Fungal Community Diversity and Soil Metabolites in Soybean Roots. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01786-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.G.; Webster, R.W.; Mueller, D.S.; Chilvers, M.I.; Faske, T.R.; Mathew, F.M.; Bradley, C.A.; Damicone, J.P.; Kabbage, M.; Smith, D.L. Integrated management of important soybean pathogens of the United States in changing climate. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Huang, X.W.; Yang, X.L.; Ye, W.W.; Wang, S.C.; Liu, M.; Su, X.; Shi, J.C.; Wang, Y.C.; Xu, J.M.; et al. Neglected contributions of residual herbicides at various levels on soybean root rot: Link with herbicide non-targeted soil microbial communities and functions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.J.; Lee, M.R.; Han, S.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.W. First Report of Soybean Root Rot Caused by Fusarium proliferatum in the Republic of Korea. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.K.; Lu, Q.S.; Wang, K.; Li, H.L. Occurrence of soybean root rot caused by Pratylenchus coffeae in Henan Province, China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Yang, F.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y. First Report of Fusarium brachygibbosum Causing Root Rot on Soybean in Northeastern China. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detranaltes, C.; Jones, C.R.; Cai, G. First Report of Fusarium fujikuroi Causing Root Rot and Seedling Elongation of Soybean in Indiana. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranathunge, K.; Thomas, R.H.; Fang, X.; Peterson, C.A.; Gijzen, M.; Bernards, M.A. Soybean root suberin and partial resistance to root rot caused by Phytophthora sojae. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrance, A.E.; Kleinhenz, M.D.; McClure, S.A.; Tuttle, N.T. Temperature, Moisture, and Seed Treatment Effects on Rhizoctonia solani Root Rot of Soybean. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.J.; Yuan, M.; Han, D.W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.Y.; Wang, S.R.; Wang, L.X.; Zhuang, X.; Zhang, C.J. Analysis on the current research status of soybean root rot in Heilongjiang Province. Soybean Sci. Technol. 2024, 02, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, G.L.; Sinclair, J.B.; Rupe, J.C. (Eds.) Compendium of Soybean Diseases, 4th ed.; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.G.; Zhao, T.X.; Khuong Gia, H.H.; Xu, L.K.; Liu, J.X.; Li, S.X.; Huang, H.W.; Ji, P.S. Pathogenicity and genetic diversity of Fusarium oxysporum causing soybean root rot in northeast China. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 10, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choi, Y.W.; Hyde, K.D.; Ho, W.H. Single spore isolation of fungi. Fungal Divers. 1999, 3, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.L.; Li, Y.Q.; Hu, K.M.; Ren, J.G.; Liu, H.M. Isolation and identification of pathogens from rotted root of Pinellia ternata in Guizhou Province. J. Microbiol. Chin. 2015, 42, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, X.L.; Dai, H.; Wang, D.P.; Zhou, H.H.; He, W.Q.; Fu, Y.; Ibrahim, F.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, G.S.; Shang, J.; et al. Identification of Fusarium species associated with soybean root rot in Sichuan Province, China. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 151, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, F.L. Sylloge Fungorum Sinicorum; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1979. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.C. Handbook of Fungal Identification; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 1979. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, K. Fusarium and its near relatives. In The Fungal Holomorph: Mitotic, Meiotic and Pleomorphic Speciation in Fungal Systematics; Reynolds, D.R., Taylor, J.W., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1993; pp. 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.P.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, N.X.; Yi, Z.G.; Dong, Z.M.; Li, Y.Q.; Fan, Y.J. Research progress on pathogen classification and resistance QTL of soybean root rot. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2025, 52, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.C.; Tang, X.Y.; Hu, S.; Zhu, W.Y.; Wu, X.P.; Sang, W.J.; Ding, H.X.; Peng, L.J. First Report of Grey Spot on Tobacco caused by Alternaria alstroemeriae in China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, Z.M.; Wen, L.; Huo, G.; Cui, C. First report of postharvest fruit rot on Gannan navel orange caused by Diaporthe unshiuensis in Jiangxi Province, China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.X.; Shi, N.N.; Ruan, H.C.; Lian, J.F.; Gan, L.; Chen, F.R. Study on Pathogenic Fungi Causing Soybean Root Rot in Yinchuan and Field Disease Control Efficiency of Seed Coating. Chin. J. Agric. Bull. 2021, 37, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Akber, M.A.; Mubeen, M.; Sohail, M.A.; Khan, S.W.; Solanki, M.K.; Khalid, R.; Abbas, A.; Divvela, P.K.; Zhou, L. Global distribution, traditional and modern detection, diagnostic, and management approaches of Rhizoctonia solani associated with legume crops. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1091288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.M.; Zhang, L.S.; Tian, X.H.; Jin, Z.T. Field Control Effect of Different Types of Pesticides on Soybean Root Rot. Agric. Eng. 2024, 14, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.D.; Li, Y.Y.; Geng, S.; Zhou, L.X.; Cao, L.D.; Huang, Q.L.; Zhao, P.Y.; Zhao, B. Preparation of core-shell fludioxoni·lmetalaxyl-M delivery system and its control efficacy against soybean root rot. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2025, 27, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.T.; Tang, Y.N.; Gu, X.H.; Zhai, Q.H.; Wang, S.L.; Xu, X.W.; Pan, H.Y.; Zhang, H. Fungicide screening and field application for controlling soybean root rot. Agrochemicals 2023, 62, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Huang, Q.F.; Yang, X.Y. Identification of the soybean root rot pathogen in Liaoning Province and its biological characteristics, sensitivity to common fungicides. J. Plant Prot. 2023, 50, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, N.P. Evaluating Chemical Seed Treatments for Fusarium Root Rot Control in Dry Beans and Field Peas. Master’s Thesis, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; You, M.P.; Laudinot, V.; Barbetti, M.J.; Aubertot, J.N. Revisiting sustainability of fungicide seed treatments for field crops. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.X.; Li, J.J.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Dong, B.; Qiao, K. Synergistic effect of combined application of a new fungicide fluopimomide with a biocontrol agent Bacillus methylotrophicus TA-1 for management of gray mold in tomato. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1991–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.L.; Luo, Y.J.; Lin, R.X.; Li, C.M.; Zhao, H.J.; Aman, H.M.; Wisal, M.A.; Dong, H.F.; Liu, D.K.; Yu, X.N.; et al. C15-bacillomycin D produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 4-9-2 suppress Fusarium graminearum infection and mycotoxin biosynthesis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1599452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.L.; Wang, G.J.; Ming, Z.; Jing, Y.; Wen, L.; Bi, Y.; Wang, L.; Lai, Y.C.; Shu, X.T.; Wang, Z. Effect of cultivation pattern on the light radiation of group canopy and yield of spring soybean (Glycine Max L. Merrill). Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, J.X.; Cui, W.Q.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Ren, Z.P.; Li, L.; Li, Y.G.; Sun, L.; Ding, J.J. Identification, characterization, and chemical management of Fusarium asiaticum causing soybean root rot in Northeast China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, G.; İmren, M.; Bozoğlu, T.; Dababat, A.A. First Report of Rhizoctonia solani AG2-1 on Roots of Wheat in Kazakhstan. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.B.; Ruff, R.; Meng, X.Q. Race of Phytophthora sojae in Iowa sobean fields. Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, V.; Chang, H.X.; Sang, H.; Jacobs, J.; Malvick, D.K.; Baird, R.; Mathew, F.M.; de Jensen, C.E.; Wise, K.A.; Mosquera, G.M.; et al. Population genomic analysis reveals geographic structure and climatic diversification for Macrophomina phaseolina isolated from soybean and dry bean across the United States, Puerto Rico, and Colombia. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.T.; Rubayet, M.T.; Khan, A.A.; Bhuiyan, M.K.A. Integrated management of fusarium root rot and wilt disease of soybean caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Int. J. Biosci. 2020, 17, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Giachero, M.L.; Declerck, S.; Marquez, N. Phytophthora root rot: Importance of the disease, current and novel methods of control. Agronomy 2022, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi-Oyetunde, O.O.; Bradley, C.A. Rhizoctonia solani: Taxonomy, population biology and management of rhizoctonia seedling disease of soybean. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Rubayet, M.T.; Bhuiyan, M.K.A. Integrated management of rhizoctonia root rot disease of soybean caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Nippon J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 1, 1018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Kong, W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J. Effect of monoculture soybean on soil microbial community in the Northeast China. Plant Soil 2010, 330, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jin, B.B.; Yang, J.W.; Liu, B.; Li, T.T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y. Risk assessment of resistance to prochloraz in Phoma arachidicola causing peanut web blotch. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2024, 203, 106025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schruefer, S.; Pschibul, A.; Wong, S.S.W.; Sae-Ong, T.; Wolf, T.; Schäuble, S.; Panagiotou, G.; Brakhage, A.A.; Aimanianda, V.; Kniemeyer, O.; et al. Distinct transcriptional responses to fludioxonil in Aspergillus fumigatus and its ΔtcsC and Δskn7 mutants reveal a crucial role for Skn7 in the cell wall reorganizations triggered by this antifungal. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliatti, F.C.; Azevedo, L.A.S.D.; Juliatti, B.C.M. Strategies of chemical protection for controlling soybean rust. In Soybean: The Basis of Yield, Biomass and Productivity; Kasai, M., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; pp. 35–62. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, G.; Enciso Maldonado, G.A.; Sanabria Velázquez, A.; Lopez Nicora, H.D.; Cazal Martínez, C.C.; Fernández Ríos, D.; Ortiz-Moreno, M.L.; Benítez Samaniega, A.; Ramírez, R.; Álvarez, G.; et al. Impact of fungicides on Asian soybean rust management in South American producing countries: A systematic study. Agriscientia 2024, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Malandrakis, A.A.; Lafka, E.; Flouri, F. Impact of fludioxonil resistance on fitness and cross-resistance profiles of Alternaria solani laboratory mutants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 161, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M.S.; Roy, M.; Abbasi, P.A.; Carisse, O.; Yurgel, S.N.; Ali, S. Why do we need alternative methods for fungal disease management in plants? Plants 2023, 12, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, M.; Guo, C.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Ma, C.Q. Using Russian dandelion allelochemicals to elevate disease resistance and improve sugar beet growth. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 303, 118889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isolate | Disease Severity (Mean ± SE) | Pathogenicity Classification | Isolate | Disease Severity (Mean ± SE) | Pathogenicity Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB21 | 73.2 ± 1.7 | H | JM32 | 77.2 ± 2.9 | H |

| HB22 | 68.1 ± 1.2 | H | JM34 | 74.6 ± 2.6 | H |

| QQ19 | 86.3 ± 2.6 | H | JM35 | 87.4 ± 2.6 | H |

| QQ25 | 74.5 ± 1.4 | H | JM37 | 84.8 ± 1.9 | H |

| JM8 | 26.5 ± 1.2 | W | HH14 | 68.7 ± 2.1 | H |

| JM13 | 75.6 ± 2.5 | H | SY20 | 23.3 ± 1.1 | W |

| JM17 | 62.1 ± 1.7 | H | SY21 | 71.4 ± 1.4 | H |

| JM18 | 46.5 ± 1.1 | M | SH15 | 65.5 ± 1.7 | H |

| JM19 | 68.0 ± 1.7 | H | SH16 | 35.2 ± 1.9 | M |

| JM20 | 74.1 ± 1.8 | H | SH18 | 76.5 ± 1.2 | H |

| JM23 | 66.1 ± 1.7 | H | HG14 | 61.8 ± 1.3 | H |

| JM24 | 48.5 ± 3.5 | M | HG17 | 86.0 ± 2.9 | H |

| JM27 | 70.6 ± 1.6 | H | HG18 | 72.5 ± 1.4 | H |

| JM29 | 64.6 ± 1.9 | H | HG19 | 86.8 ± 3.0 | H |

| JM30 | 74.7 ± 2.1 | H | HG20 | 93.2 ± 0.9 | H |

| Fungicides | EC50 (μg·mL−1) | Maximum/Minimum EC50 | Mean EC50 Value (µg·mL−1) | Fungal Sensitivity to Fungicides 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fludioxonitrile | 0.000107–0.0005714 | 6.6 | 0.00039 | S |

| Prochloraz | 0.000151–0.002607 | 17.2 | 0.000729 | S |

| Tebuconazole | 0.008526–0.8686 | 10.2 | 0.019172 | R |

| Difenoconazole | 0.008731–0.3614 | 41.4 | 0.051595 | R |

| Pyraclostrobin | 0.004188–0.1091 | 26.1 | 0.015113 | R |

| Carbendazim | 0.002503–0.5083 | 203.1 | 0.031918 | R |

| Fungicides | Active Ingredient Content (g/100 kg) | Incidence (%) | Disease Index 1 | Control Efficacy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| —— | —— | 91.67 ± 0.04 | 49.33 ± 6.65 a | —— |

| Fludioxonil | 15 | 53.33 ± 0.10 | 18.22 ± 2.18 c | 63.07 |

| Prochloraz | 18 | 61.67 ± 0.10 | 26.22 ± 4.53 b | 46.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Shen, Z.; Li, Y. Identification Pathogenicity Distribution and Chemical Control of Rhizoctonia solani Causing Soybean Root Rot in Northeast China. Agronomy 2026, 16, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030281

Wang S, Liu J, Wang C, Wu J, Shen Z, Li Y. Identification Pathogenicity Distribution and Chemical Control of Rhizoctonia solani Causing Soybean Root Rot in Northeast China. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030281

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuni, Jinxin Liu, Chen Wang, Jianzhong Wu, Zhongbao Shen, and Yonggang Li. 2026. "Identification Pathogenicity Distribution and Chemical Control of Rhizoctonia solani Causing Soybean Root Rot in Northeast China" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030281

APA StyleWang, S., Liu, J., Wang, C., Wu, J., Shen, Z., & Li, Y. (2026). Identification Pathogenicity Distribution and Chemical Control of Rhizoctonia solani Causing Soybean Root Rot in Northeast China. Agronomy, 16(3), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030281