Bacillus velezensis HZ33 Controls Potato Black Scurf and Improves the Potato Rhizosphere Microbiome and Potato Growth and Yield

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculants and Fungicide

2.2. Field Experiment Design

2.3. Soil Sample Collection

2.4. Promotion Assay

2.5. Control Efficacy, Yield, and Commercial Rate Assay

2.6. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.7. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

2.8. Sequencing Data Processing and Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Growth-Promoting Effects of B. velezensis HZ33 on Potatoes

3.2. Field Efficacy of B. velezensis HZ33 Against Potato Black Scurf Disease

3.3. Effects of Bacillus velezensis HZ33 on the Potato Yield and Commercial Rate

3.4. Effects of B. velezensis HZ33 Application on Soil Chemical Properties

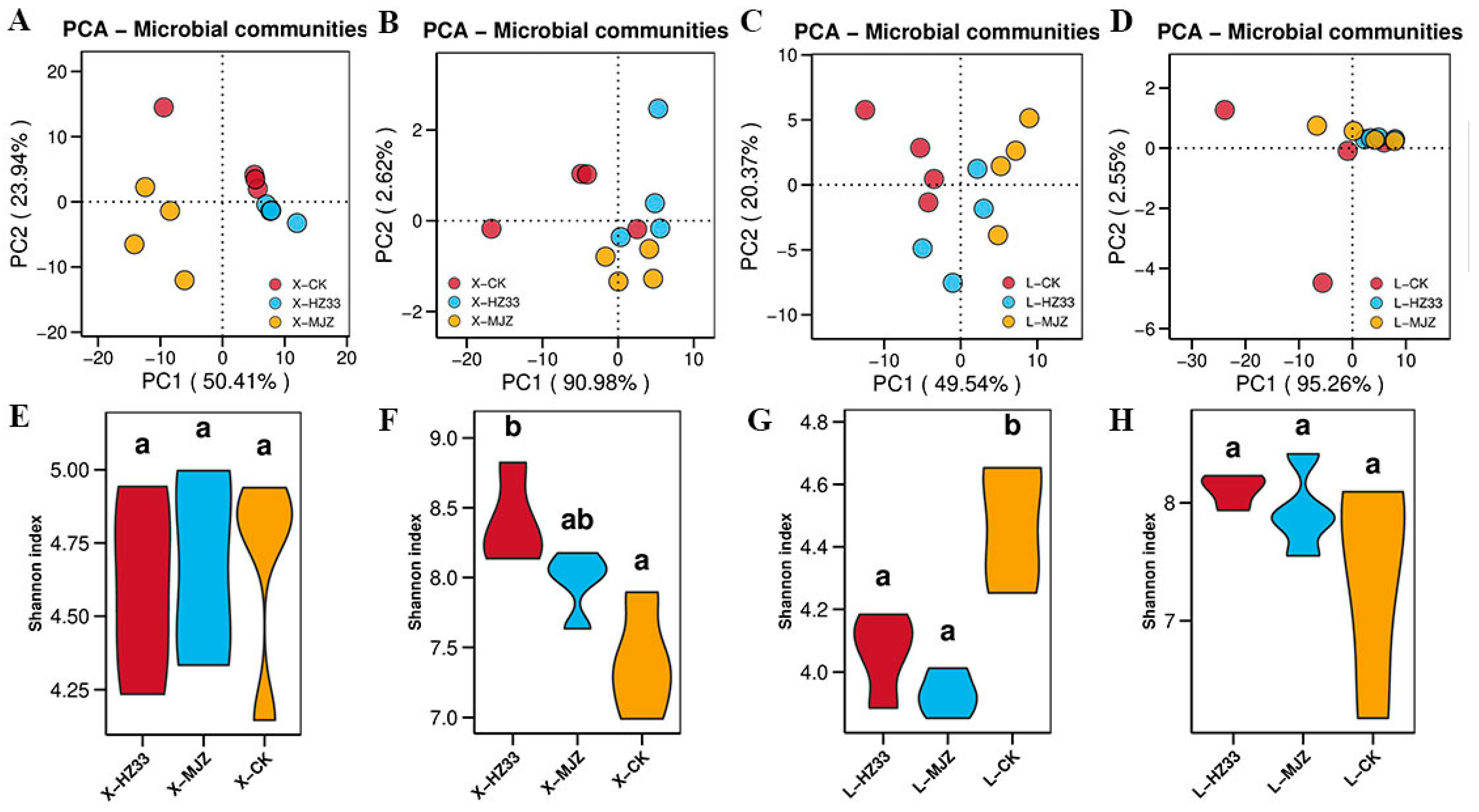

3.5. Alpha and Beta Diversity of the Microbial Community in Rhizosphere Soils

3.6. Composition of the Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Community at the Phyla Level

3.7. Composition of the Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Community at the Genus Level

3.8. LEfSe Analysis of Fungal and Bacterial Communities

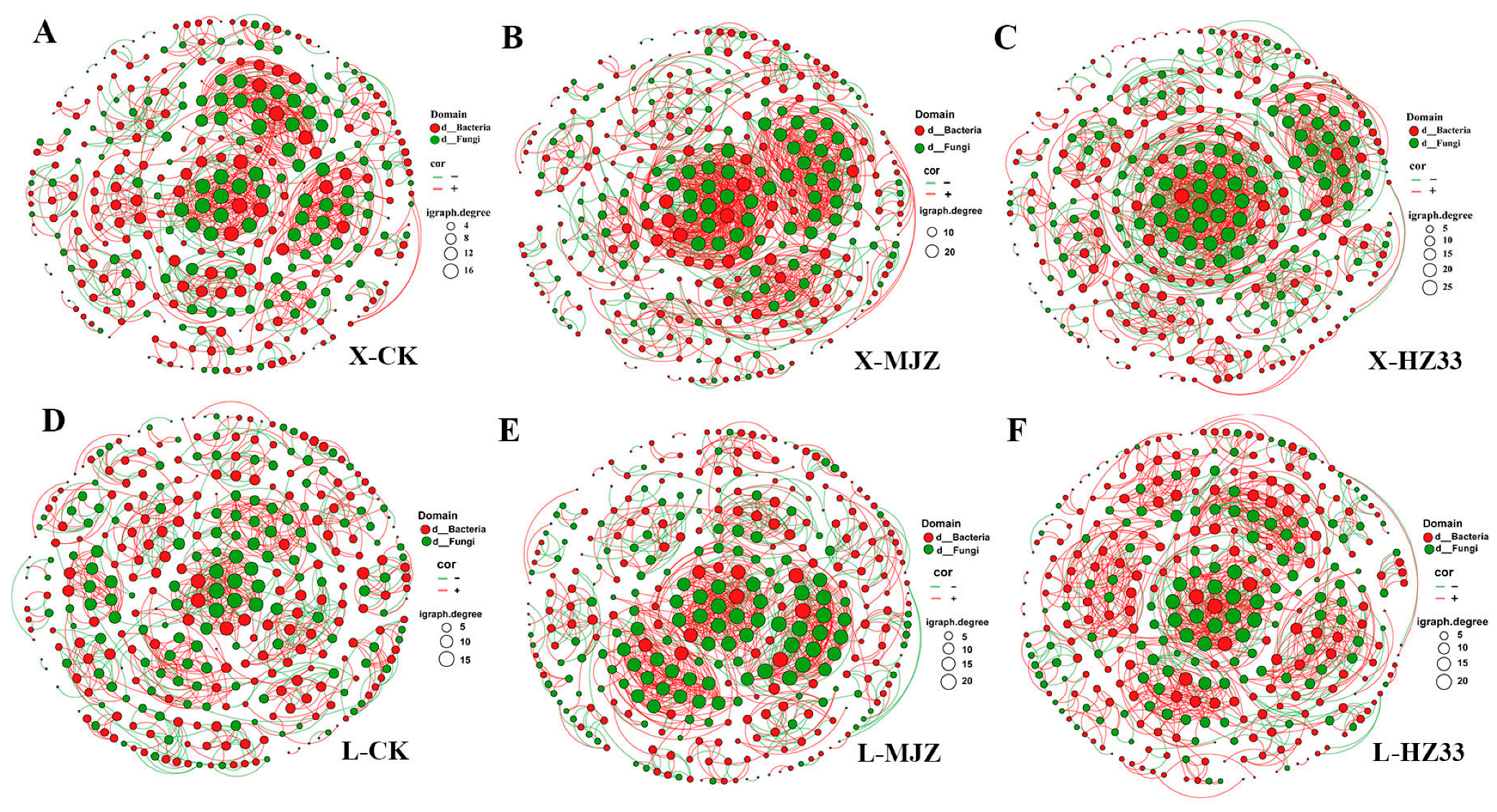

3.9. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

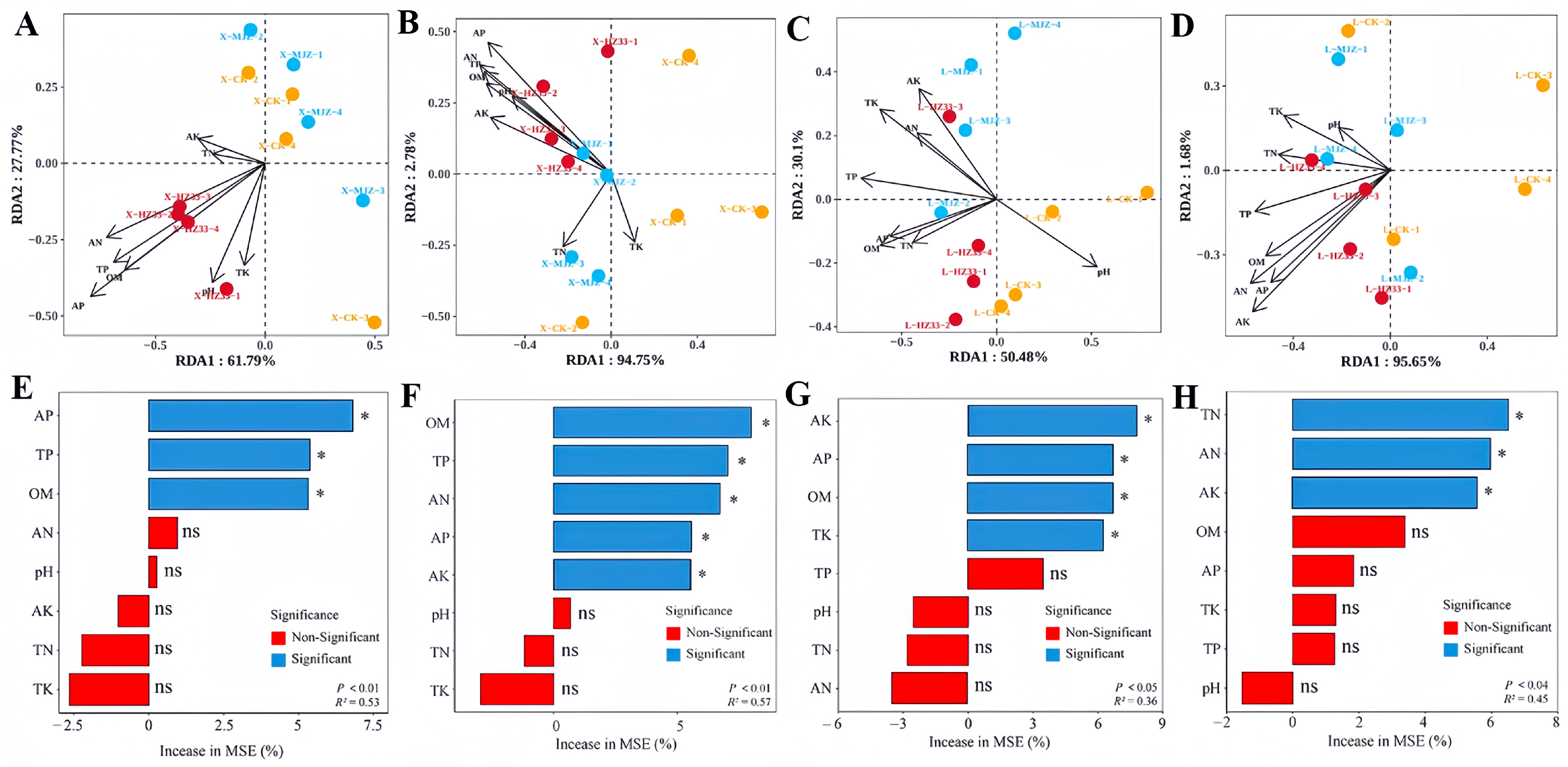

3.10. Analysis of Rhizosphere Soil Chemical Properties and Microbial Communities

3.11. Correlation Analysis Between the Microbial Community and Potato Black Scurf Disease Index

4. Discussion

4.1. Bacillus velezensis HZ33 Promotes the Growth of Potato Plants, Increases the Potato Yield, and Effectively Controls Potato Black Scurf Caused by R. solani

4.2. Application of B. velezensis HZ33 Increases Bacterial Diversity, Suppresses Major Plant Pathogens, and Enriches Beneficial Microbes in the Potato Rhizosphere

4.3. Application of B. velezensis HZ33 Improves the Soil Nutrient Status and Shapes the Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure

4.4. Application of B. velezensis HZ33 Increases the Complexity of Rhizosphere Fungal–Bacterial Co-Occurrence Networks

4.5. Major Rhizosphere Pathogens Are Positively Correlated with Potato Black Scurf Severity, Whereas Beneficial Bacteria Show Negative Correlations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, C.M.; Auat Cheein, F. Machinery for potato harvesting: A state-of-the-art review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1156734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, R.P. Biological control of soilborne diseases in organic potato production using hypervirulent strains of Rhizoctonia solani. Biol. Agric. Heretic. 2020, 36, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Lal, M.; Sagar, S.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, M. Black scurf of potato: Insights into biology, diagnosis, detection, host-pathogen interaction, and management strategies. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2024, 49, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yue, L.; Constantie, U.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Dun, Z.; et al. Effectively controlling Fusarium root rot disease of Angelica sinensis and enhancing soil fertility with a novel attapulgite-coated biocontrol agent. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslennikova, V.S.; Tsvetkova, V.P.; Shelikhova, E.V.; Selyuk, M.P.; Alkina, T.Y.; Kabilov, M.P.; Dubovskiy, I.M. Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Mix Suppresses Rhizoctonia Disease and Improves Rhizosphere Microbiome, Growth and Yield of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, X.; Deng, S.; Dong, X.; Song, A.; Yao, J.; Fang, W.; Chen, F. The Effects of Fungicide, Soil Fumigant, Bio-Organic Fertilizer and Their Combined Application on Chrysanthemum Fusarium Wilt Controlling, Soil Enzyme Activities and Microbial Properties. Molecules 2016, 21, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Lu, P.; Xu, T.; Pan, K. Three Preceding Crops Increased the Yield of and Inhibited Clubroot Disease in Continuously Monocropped Chinese Cabbage by Regulating the Soil Properties and Rhizosphere Microbial Community. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamone, A.L.; Gundersen, B.; Inglis, D.A. Clonostachys rosea, a potential biological control agent for Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 causing black scurf on potato. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, P.L. Impacts of biocontrol products on Rhizoctonia disease of potato and soil microbial communities, and their persistence in soil. Crop Prot. 2016, 90, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, T.; Sumera, Y.; Fauzia, Y.H. Biological control of potato black scurf by rhizosphere associated bacteria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2010, 41, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Mu, R.R.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Islam, R.; Su, X.; Tian, Y. Biological Control Effect of Antagonistic Bacteria on Potato Black Scurf Disease Caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Agronomy 2024, 14, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debez, I.B.S.; Alaya, A.B.; Karkouch, I.; Khiari, B.; Garcia-Caparros, P.; Alyami, N.M.; Debez, A.; Tarhouni, B.; Djébali, N. In vitro and in vivo antifungal efficacy of individual and consortium Bacillus strains in controlling potato black scurf and possible development of spore-based fungicide. Biol. Control. 2024, 193, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.; Marchant, H.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, J.R.; Miller, A.J.; Whalley, W.R.; Mooney, S.J.; Sturrock, C.J. Quantifying the impact of microbes on soil structural development and behaviour in wet soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 74, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, E.B.; Hu, P.; Wang, A.S.; Hons, F.M.; Gentry, T.J. Differential impacts of brassicaceous and nonbrassicaceous oilseed meals on soil bacterial and fungal communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 83, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.S.; Mills, N.J. Single vs. multiple introductions in biological control: The roles of parasitoid efficiency, antagonism and niche overlap. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 41, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Paulitz, T.C.; Steinberg, C.; Alabouvette, C.; Mo¨enne-Loccoz, Y. The rhizosphere: A playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil. 2008, 321, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Alchanatis, V. The potential of airborne hyperspectral images to detect leaf nitrogen content in potato fields. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Material and Environmental Engineering (ICMAEE 2014), Jiujiang, China, 21–23 March 2014; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.R.; Radl, V.; Treder, K.; Michałowska, D.; Pritsch, K.; Schloter, M. The rhizosphere microbiome of 51 potato cultivars with diverse plant growth characteristics. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2024, 100, fiae088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomloudi, E.E.; Tsalgatidou, P.C.; Baira, E.; Papadimitriou, K.; Venieraki, A.; Katinakis, P. Genomic and metabolomic insights into secondary metabolites of the novel Bacillus halotolerant hil4, an endophyte with promising antagonistic activity against gray mold and plant growth promoting potential. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Weon, H.Y.; Sang, M.K.; Song, J. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus velezensis M75, a biocontrol agent against fungal plant pathogens, isolated from cotton waste. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 241, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirttilä, A.M.; Mohammad Parast Tabas, H.; Baruah, N.; Koskimäki, J.J. Biofertilizers and biocontrol agents for agriculture: How to identify and develop new potent microbial strains and traits. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriss, R.; Chen, X.; Rueckert, C.; Blom, J.; Becker, A.; Baumgarth, B.; Fan, B.; Pukall, R.; Schumann, P.; Spröer, C.; et al. Relationship of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens clades associated with strains DSM7T and FZB42T: A proposal for Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. amyloliquefaciens subsp. nov. and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum subsp. nov. based on complete genome sequence comparisons. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 1786–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Tang, X.; Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Tao, F.; Li, F.; Wang, Z. Characteristics and Application of a Novel Species of Bacillus: Bacillus velezensis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, T.A.; Lee, G.; Kim, K.; Hahn, D.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, W.C. Biocontrol of peach gummosis by Bacillus velezensis KTA01 and its antifungal mechanism. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Yu, J.; Yang, L.; Qiao, J.; Qi, Z.; Yu, M.; Du, Y.; Song, T.; Cao, H.; Pan, X. Surfactins and Iturins Produced by Bacillus velezensis Jt84 Strain Synergistically Contribute to the Biocontrol of Rice False Smut. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosela, M.; Andrade, G.; Massucato, L.R.; de Araujo Almeida, S.R.; Nogueira, A.F.; de Lima Filho, R.B.; Zeffa, D.M.; Mian, S.; Higashi, A.Y.; Shimizu, G.D.; et al. Bacillus velezensis strain Ag75 as a new multifunctional agent for biocontrol, phosphate solubilization and growth promotion in maize and soybean crops. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaturova, A.; Shternshis, M.; Tsvetkova, V.; Shpatova, T.; Maslennikova, V.; Zhevnova, N.; Homyak, A. Biological control of important fungal diseases of potato and raspberry by two Bacillus velezensis strains. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Updating the 97% identity threshold for 16S ribosomal RNA OTUs. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2371–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Spakowicz, D.J.; Hong, B.Y.; Petersen, L.M.; Demkowicz, P.; Chen, L.; Leopold, S.R.; Hanson, B.M.; Agresta, H.O.; Gerstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Guo, R.; Ma, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Fan, Y.; Ju, Y.; Zhao, B.; Gao, Y.; Qian, L.; et al. Stressful events induce long-term gut microbiota dysbiosis and associated post-traumatic stress symptoms in healthcare workers fighting against COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 303, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Weber, C.F. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Fang, F.; Cao, J.; Su, Y. Distinct effects of hypochlorite types on the reduction of antibiotic resistance genes during waste activated sludge fermentation: Insights of bacterial community, cellular activity, and genetic expression. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 124010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Reich, P.B.; Banerjee, S.; van der Heijden, M.G.; Wei, X. Erosion reduces soil microbial diversity, network complexity and multifunctionality. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2474–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2021, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of the Biocontrol Efficiency of Bacillus subtilis Wettable Powder on Pepper Root Rot Caused by Fusarium solani. Pathogens 2023, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z.; Dou, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Lu, B.; Gao, J. Evaluation of the Antifungal and Biochemical Activities of Fungicides and Biological Agents against Ginseng Sclerotinia Root Rot Caused by Sclerotinia nivalis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cawoy, H.; Bettiol, W.; Fickers, P.; Ongena, M. Bacillus-based biological control of plant diseases. In Pesticides in the Modern World—Pesticides Use and Management; Intech Open: London, UK, 2011; pp. 273–302. [Google Scholar]

- Fira, D.; Dimkić, I.; Berić, T.; Lozo, J.; Stanković, S. Biological control of plant pathogens by Bacillus species. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 285, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante, P.; Venice, F. Mucoromycota: Going to the roots of plant-interacting fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2020, 34, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, J.; Yue, F.; Yan, X.; Wang, F.; Bloszies, S.; Wang, Y. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation and biochar amendment on maize growth, cadmium uptake and soil cadmium speciation in Cd-contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2018, 194, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Chao, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Rhizosphere microbial community manipulated by 2 years of consecutive biofertilizer application associated with banana Fusarium wilt disease suppression. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, E.A.; Vatsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Klenk, H.P.; van Wezel, G.P. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Ruan, Y.; Tao, C.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Continuous application of bioorganic fertilizer induced resilient culturable bacteria community associated with banana Fusarium wilt suppression. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Shen, T.; Guo, W.; Wang, R. Shifts in microbial community function and structure along the successional gradient of coastal wetlands in Yellow River Estuary. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2012, 49, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ahmed, W.; Li, G.; He, Y.; Mohanty, M.; Li, Z.; Shen, T. A Novel Plant-Derived Biopesticide Mitigates Fusarium Root Rot of Angelica sinensis by Modulating the Rhizosphere Microbiome and Root Metabolome. Plants 2024, 13, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, W.; Long, T.; Ma, J.; Wu, N.; Mo, W.D.; Zhou, Z.; Jin, J.; Zhou, H.; Ding, H. Bacillus velezensis GUAL210 control on edible rose black spot disease and soil fungal community structure. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1199024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, E.; Hanaka, A. Mortierella Species as the Plant Growth-Promoting Fungi Present in the Agricultural Soils. Agriculture 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larran, S.; Simón, M.R.; Moreno, M.V.; Santamarina Siurana, M.P.; Perelló, A. Endophytes from wheat as biocontrol agents against tan spot disease. Biol. Control 2016, 92, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: From diversity and genomics to functional role in environmental remediation and plant growth. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; McInroy, J.A.; Kloepper, J.W. The Interactions of Rhizodeposits with Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria in the Rhizosphere: A Review. Agriculture 2019, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.S.; Cha, S.; Kim, M.K.; Jheong, W.; Seo, T.; Srinivasan, S. Flavisolibacter swuensis sp. nov. isolated from soil. J. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Sharma, N.; Tapwal, A.; Kumar, A.; Verma, G.S.; Meena, M.; Seth, C.S.; Swapnil, P. Soil Microbiome: Diversity, Benefits and Interactions with Plants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Huang, B.L.; Fernandez-Garcia, V.; Miesel, J.; Yan, L.; Lv, C.Q. Biochar and rhizobacteria amendments improve several soil properties and bacterial diversity. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, G.; Hao, F.; He, W.; Ran, Q.; Nie, G.; Huang, L.; Wang, X.; Yuan, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X. Effect of Biogas Slurry on the Soil Properties and Microbial Composition in an Annual Ryegrass-Silage Maize Rotation System over a Five-Year Period. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, T. Characteristics of the Soil Microbial Community Structure under Long-Term Chemical Fertilizer Application in Yellow Soil Paddy Fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, N.; Li, J.; Zhou, G. Trophic relationships between protists and bacteria and fungi drive the biogeography of rhizosphere soil microbial community and impact plant physiological and ecological functions. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 280, 127603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jin, J.; Lu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z. Bacterial diversity loss weakens community functional stability. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huusko, K.; Manninen, O.H.; Myrsky, E.; Stark, S. Soil fungal and bacterial communities reflect differently tundra vegetation state transitions and soil physico-chemical properties. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pommier, T.; Yin, Y.; Wang, J.; Gu, S.; Jousset, A.; Keuskamp, J.; Wang, H.; Wei, Z.; Xu, Y. Indirect reduction of Ralstonia solanacearum via pathogen helper inhibition. ISME J. 2022, 16, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, N.; Koss, M.J.; Greco, C.; Nickles, G.; Wiemann, P.; Keller, N.P. Secreted secondary metabolites reduce bacterial wilt severity of tomato in bacterial–fungal co-infections. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Incidence Rate (%) | Disease Index (%) | Control Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-HZ33 | 31.18 ± 1.36 c | 9.48 ± 1.19 c | 67.72 a |

| X-MJZ | 38.31 ± 3.72 b | 12.93 ± 0.92 b | 55.96 b |

| X-CK | 58.37 ± 2.63 a | 29.35 ± 1.52 a | - |

| L-HZ33 | 28.95 ± 2.18 b | 8.04 ± 0.74 c | 59.84 a |

| L-MJZ | 30.49 ± 5.64 b | 9.91 ± 0.63 b | 50.41 b |

| L-CK | 59.48 ± 8.35 a | 19.99 ± 1.13 a | - |

| Index | Xindaping | Longshu 7 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-HZ33 | X-MJZ | X-CK | L-HZ33 | L-MJZ | L-CK | |

| pH | 7.61 ± 0.24 a | 7.50 ± 0.18 a | 7.40 ± 0.01 a | 7.55 ± 0.08 a | 7.49 ± 0.04 a | 7.48 ± 0.05 a |

| Organic Matter (OM) (g/kg) | 17.44 ± 1.00 a | 15.05 ± 1.49 ab | 13.40 ± 1.06 b | 18.39 ± 0.20 a | 16.12 ± 0.56 b | 15.13 ± 1.25 b |

| Total Nitrogen (TN) (g/kg) | 1.02 ± 0.09 a | 1.02 ± 0.08 a | 0.99 ± 0.18 a | 1.15 ± 0.13 a | 1.08 ± 0.04 a | 1.04 ± 0.08 a |

| Total Phosphorus (TP) (g/kg) | 0.97 ± 0.06 a | 0.84 ± 0.05 b | 0.77 ± 0.07 b | 0.97 ± 0.02 a | 0.88 ± 0.03 ab | 0.78 ± 0.09 b |

| Total Potassium (TK) (g/kg) | 17.58 ± 0.53 a | 17.17 ± 0.37 ab | 16.58 ± 0.48 b | 17.57 ± 0.27 a | 16.65 ± 0.23 ab | 16.10 ± 1.16 b |

| Available Nitrogen (AN) (mg/kg) | 65.93 ± 3.24 a | 59.83 ± 3.65 b | 56.58 ± 1.33 b | 57.64 ± 2.49 a | 55.97 ± 3.10 ab | 52.88 ± 3.92 b |

| Available Phosphorus (AP) (mg/kg) | 49.30 ± 1.23 a | 23.97 ± 0.38 b | 22.64 ± 5.14 b | 49.26 ± 2.13 a | 28.93 ± 0.51 b | 20.46 ± 1.68 c |

| Available Potassium (AK) (mg/kg) | 155.30 ± 11.60 a | 152.41 ± 4.57 a | 135.40 ± 4.36 b | 140.54 ± 5.71 a | 140.36 ± 1.94 a | 127.86 ± 5.99 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Tao, Y.; Dong, A.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Xie, Z.; Tian, Y.; Shen, T. Bacillus velezensis HZ33 Controls Potato Black Scurf and Improves the Potato Rhizosphere Microbiome and Potato Growth and Yield. Agronomy 2026, 16, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010087

Li Z, Wang C, Tao Y, Dong A, Feng Y, Li J, Cheng J, Xie Z, Tian Y, Shen T. Bacillus velezensis HZ33 Controls Potato Black Scurf and Improves the Potato Rhizosphere Microbiome and Potato Growth and Yield. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010087

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhaoyu, Chao Wang, Yunpeng Tao, Aixia Dong, Yuzi Feng, Jiajia Li, Jin Cheng, Zhihong Xie, Yongqiang Tian, and Tong Shen. 2026. "Bacillus velezensis HZ33 Controls Potato Black Scurf and Improves the Potato Rhizosphere Microbiome and Potato Growth and Yield" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010087

APA StyleLi, Z., Wang, C., Tao, Y., Dong, A., Feng, Y., Li, J., Cheng, J., Xie, Z., Tian, Y., & Shen, T. (2026). Bacillus velezensis HZ33 Controls Potato Black Scurf and Improves the Potato Rhizosphere Microbiome and Potato Growth and Yield. Agronomy, 16(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010087