Nitrogen Addition Reduces Negative Plant-Soil Feedback in Invasive Spartina alterniflora: Preliminary Findings from a Mesocosm Experiment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Mesocosm Experiment

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Properties Under Different Experimental Treatments

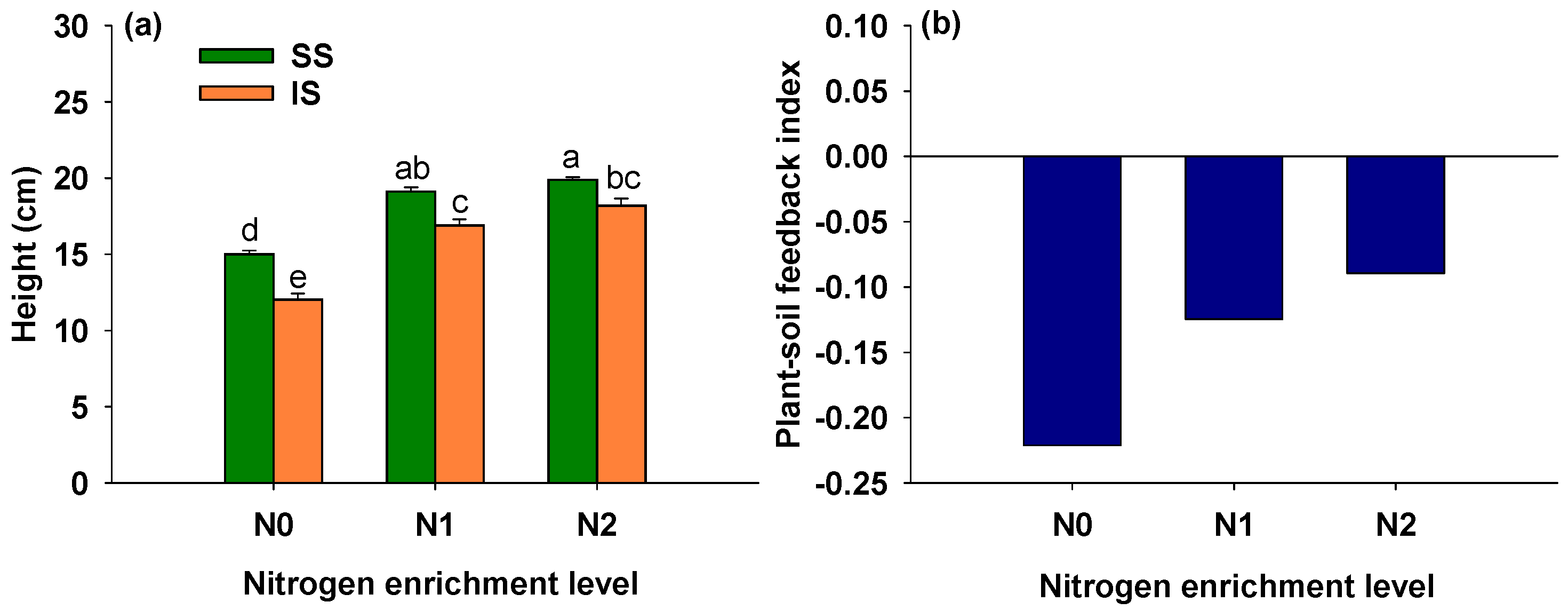

3.2. Effects of Soil Condition and Nitrogen Addition on Height of S. alterniflora

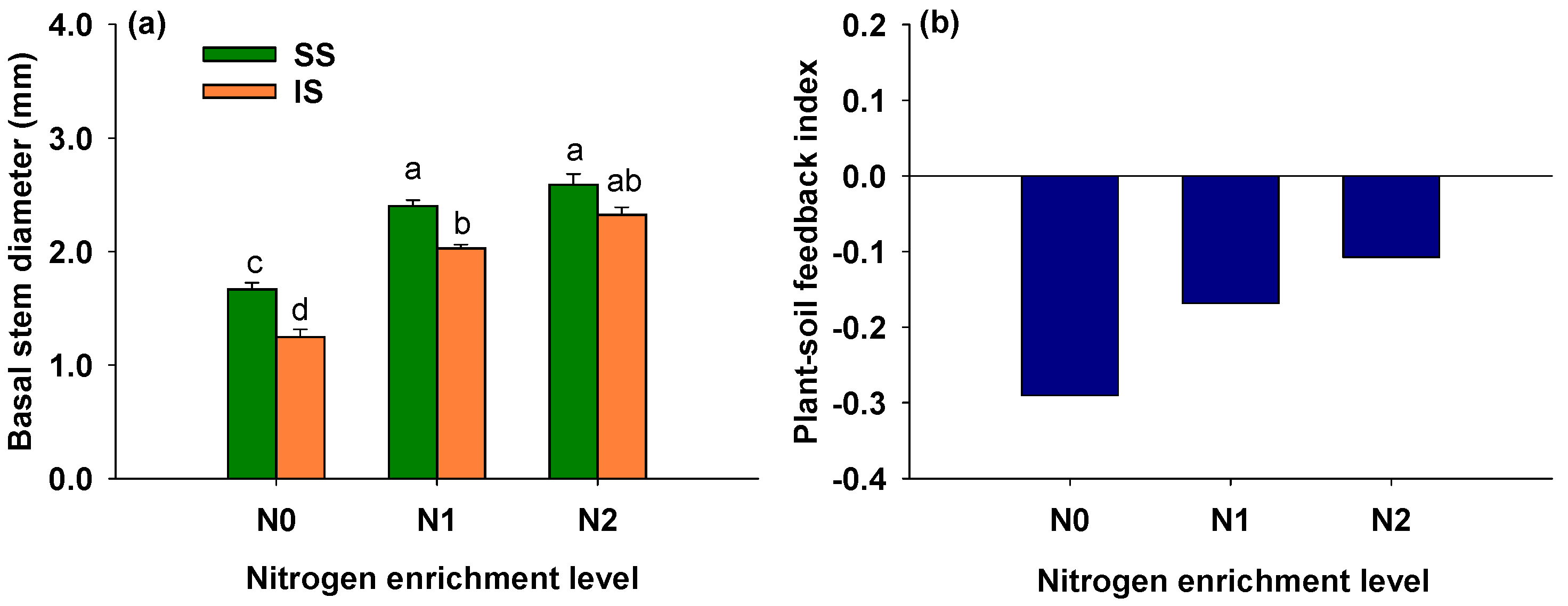

3.3. Effects of Soil Condition and Nitrogen Addition on Basal Stem Diameter of S. alterniflora

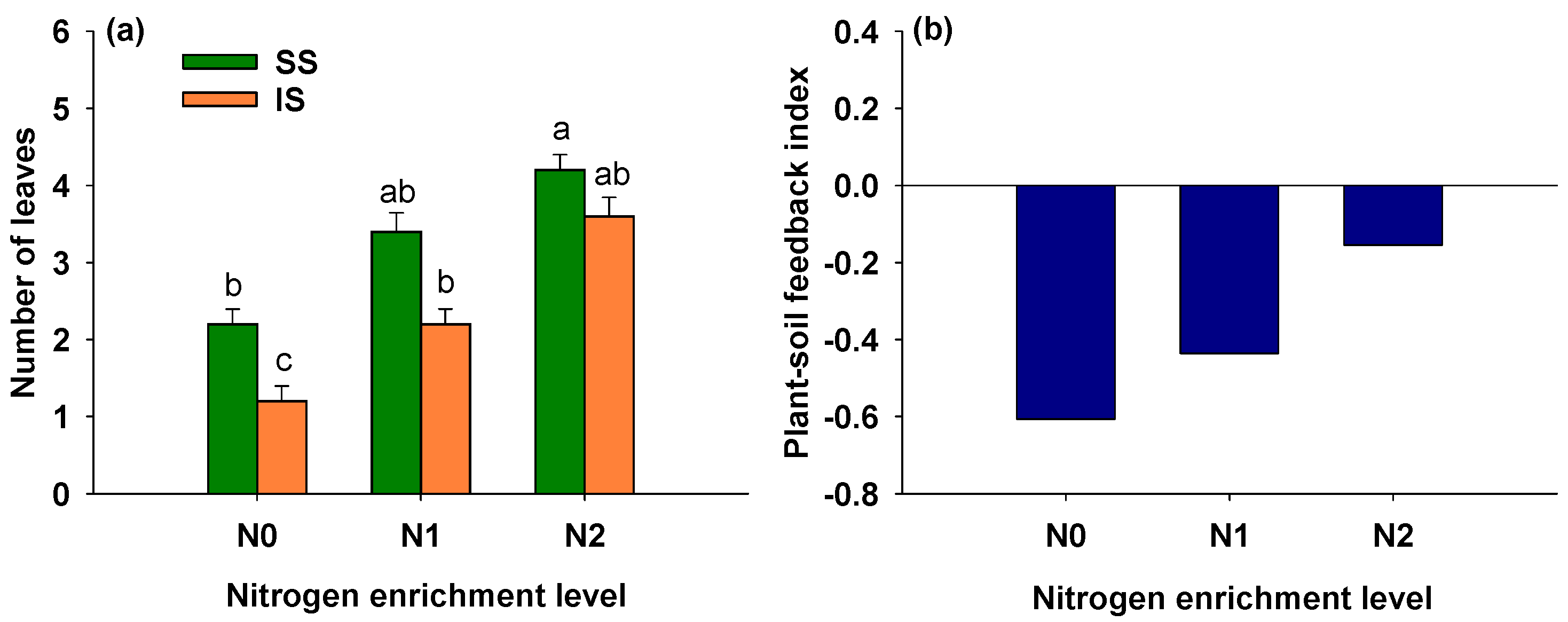

3.4. Effects of Soil Condition and Nitrogen Addition on Number of Leaves of S. alterniflora

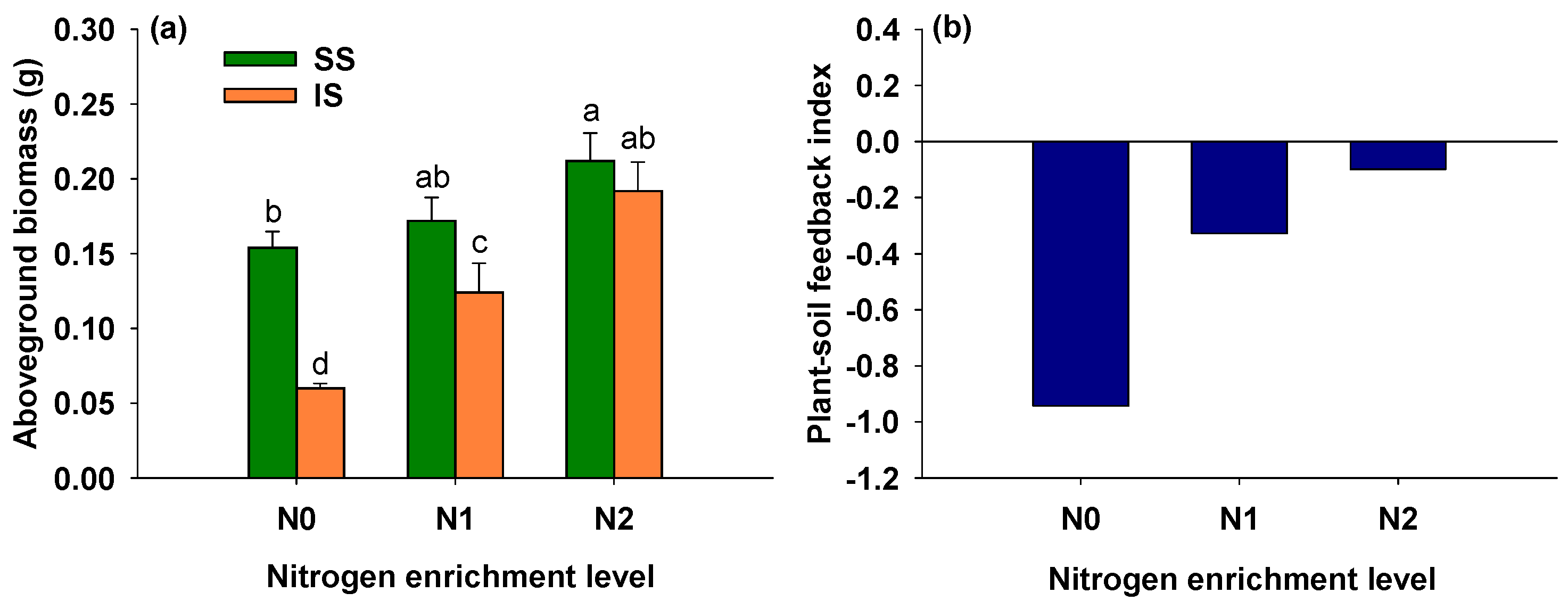

3.5. Effects of Soil Condition and Nitrogen Addition on Aboveground Biomass of S. alterniflora

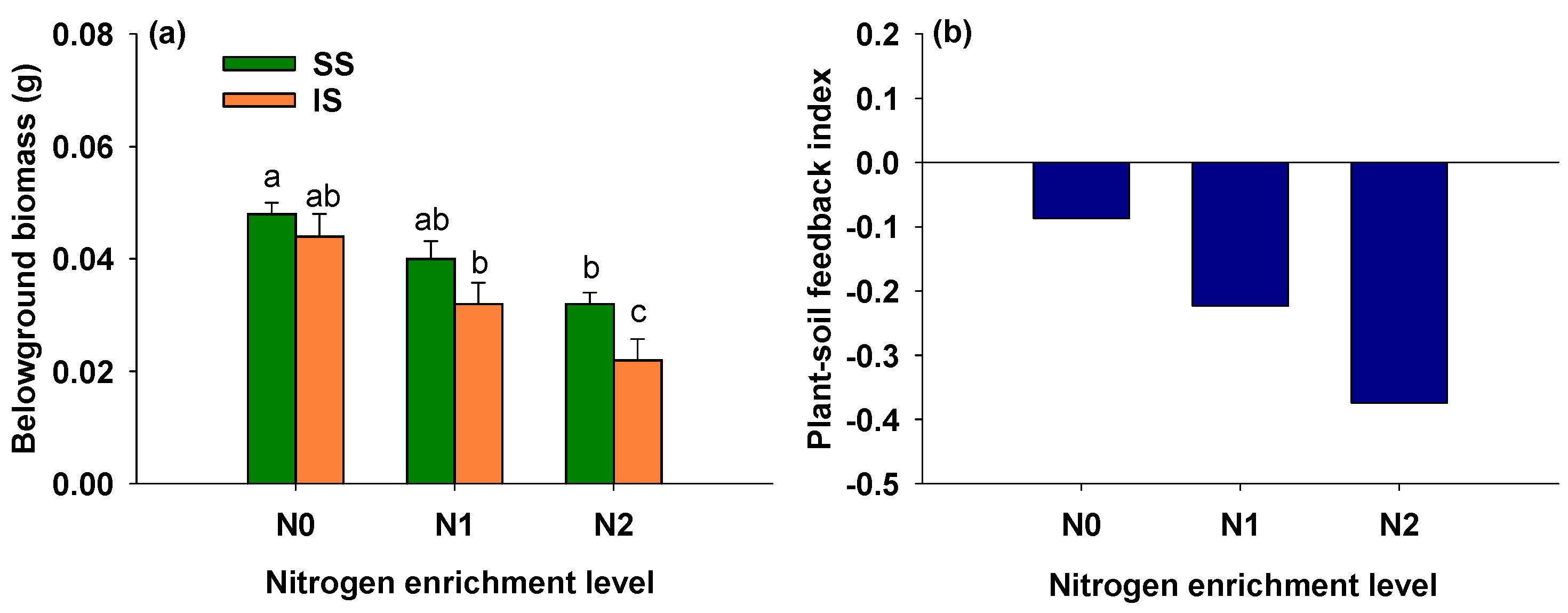

3.6. Effects of Soil Condition and Nitrogen Addition on Belowground Biomass of S. alterniflora

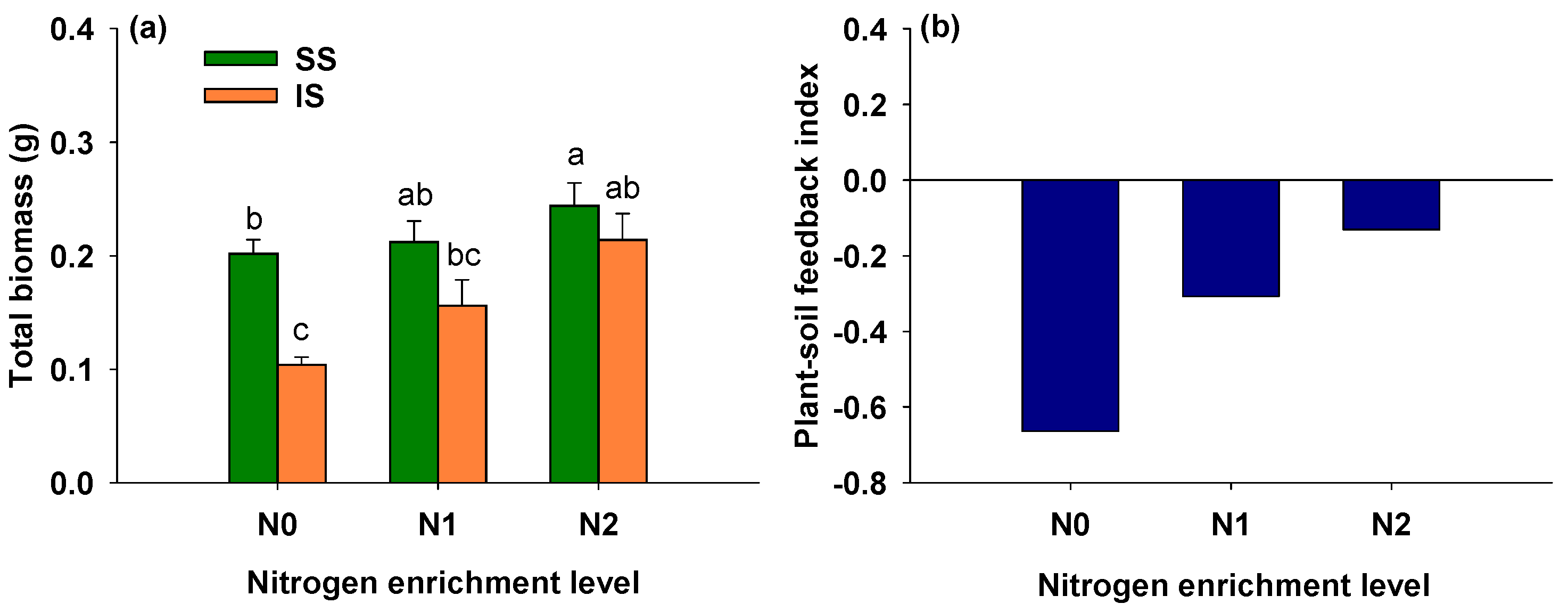

3.7. Effects of Soil Condition and Nitrogen Addition on Total Biomass of S. alterniflora

4. Discussion

4.1. Aboveground Growth of S. alterniflora under Different Soil Conditions and Nitrogen Addition Levels

4.2. Belowground Biomass of S. alterniflora under Different Soil Conditions and Nitrogen Addition Levels

4.3. Plant–Soil Feedback in Invasive Spartina alterniflora Across Nitrogen Addition Levels

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, W.W.; Zhang, Y.H.; Chen, X.C.; Maung-Douglass, K.; Strong, D.R.; Pennings, S.C. Contrasting plant adaptation strategies to latitude in the native and invasive range of Spartina alterniflora. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.J.; Javed, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhong, S.; Cheng, Z.; Rehman, A.; Du, D.L.; Li, J. Impact of Spartina alterniflora Invasion in Coastal Wetlands of China: Boon or Bane? Biology 2023, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Liu, W.W.; Pennings, S.C.; Li, B. Lessons from the invasion of Spartina alterniflora in coastal China. Ecology 2023, 104, e3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Gao, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.H.; Zhao, B. Spartina alterniflora with high tolerance to salt stress changes vegetation pattern by outcompeting native species. Ecosphere 2014, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Qu, G.J.; Jia, J.; Li, D.Z.; Sun, Y.M.; Liu, L. Long-term Spartina alterniflora invasion simplified soil seed bank and regenerated community in a coastal marsh wetland. Ecol. Appl. 2024, 34, e2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, G.B.; Zhao, Y.J.; Wang, J.B.; Wu, P.Q.; Ma, Y. Ecological effects analysis of Spartina alterniflora invasion within Yellow River delta using long time series remote sensing imagery. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 249, 107111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Ge, Z.M.; Tan, L.S.; Xie, L.N.; Li, Y.L. Multiple competitive superiority made a great successful invasion of Spartina alterniflora in Eastern China: Hints for management. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; An, S.Q.; Ma, Z.J.; Zhao, B.; Chen, J.K.; Li, B. Invasive Spartina alterniflora: Biology, ecology and management. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 2006, 44, 559–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J. Nitrogen in the environment. Science 2019, 363, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N.; Galloway, J.N. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 2008, 451, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.H.; Li, J.N.; Zhou, C.H.; Lei, K.; Jiang, W.J. Source analysis of nitrogen pollution in basin by export coefficient modeling and microbial source tracking with mutual verification. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1527098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Krause-Jensen, D. Intervention options to accelerate ecosystem recovery from coastal eutrophication. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E.; Díaz, R.J.; Justic, D. Global change and eutrophication of coastal waters. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2009, 66, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.M. Eutrophication, harmful algae and biodiversity-Challenging paradigms in a world of complex nutrient changes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.S.; Warren, R.S.; Deegan, L.A.; Mozdzer, T.J. Saltmarsh plant responses to eutrophication. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 2647–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.R.; DeLaune, R.D.; Justic, D.; Day, J.W.; Pahl, J.; Lane, R.R.; Boynton, W.R.; Twilley, R.R. Consequences of Mississippi River diversions on nutrient dynamics of coastal wetland soils and estuarine sediments: A review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 224, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwillie, C.; McCoy, M.W.; Peralta, A.L. Long-term nutrient enrichment, mowing, and ditch drainage interact in the dynamics of a wetland plant community. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e03252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.H. Eutrophication of freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems—A global problem. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2003, 10, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Z.; van der Putten, W.H.; Klironomos, J.; Zhang, F.S.; Zhang, J.L. Steering plant-soil feedback for sustainable agriculture. Science 2025, 389, eads2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouz, J. Plant-soil feedback across spatiotemporal scales from immediate effects to legacy. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2024, 189, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, J.A.; Shoemaker, L.G.; Diez, J.M. Environmental context alters plant-soil feedback effects on plant coexistence. Ecology 2025, 106, e70170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, K.M.; Knight, T.M. Competition overwhelms the positive plant-soil feedback generated by an invasive plant. Oecologia 2017, 183, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchesneau, K.; Golemiec, A.; Colautti, R.I.; Antunes, P.M. Functional shifts of soil microbial communities associated with Alliaria petiolata invasion. Pedobiologia 2021, 84, 150700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.C.; Sun, J.; Shi, P.L. Mechanism of plant-soil feedback in a degraded alpine grassland on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idbella, M.; Abd-ElGawad, A.M.; Chouyia, F.E.; Bonanomi, G. Impact of soil legacy on plant-soil feedback in grasses and legumes through beneficial and pathogenic microbiota accumulation. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1454617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, A.J.; Shen, H.H.; Xu, L.C.; Zhao, M.Y.; Yan, Z.B.; Fang, J.Y. Linking nutrient resorption stoichiometry with plant growth under long-term nitrogen addition. For. Ecosyst. 2024, 11, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.B.; Dong, C.C.; Yao, X.D.; Wang, W. Effects of nitrogen addition on plant biomass and tissue elemental content in different degradation stages of temperate steppe in northern China. J. Plant Ecol. 2018, 11, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.W.; Zhao, L.J.; Yi, H.P.; Lan, S.Q.; Chen, L.; Han, G.X. Nitrogen addition alters plant growth in China’s Yellow River Delta coastal wetland through direct and indirect effects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1016949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvaja, R.; Ramesh, R.; Ray, A.K.; Rixen, T. Nitrogen cycling: A review of the processes, transformations and fluxes in coastal ecosystems. Curr. Sci. 2008, 94, 1419–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Jin, L.Q.; Jin, J.; Ibánhez, J.S.P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. Exploring feedback mechanisms for nitrogen and organic carbon cycling in tropical coastal zones. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 996655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Wang, F.; Yan, W.J.; Lv, S.C.; Li, Q.Q.; Yu, Q.B.; Wang, J. Enhanced nitrogen imbalances in agroecosystems driven by changing cropping systems in a coastal area of eastern China: From field to watershed scale. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2019, 21, 1532–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, Q.; Wan, N.F.; Liu, H.; Guo, H.Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Reducing nitrogen inputs mitigates Spartina invasion in the Yangtze estuary. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 61, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Qu, G.J.; Jia, J.; Xu, H.W.; Li, D.Z. Water and nitrogen coupling regulates the present and future restoration trends under Spartina alterniiora invasion in a coastal salt marsh. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 209, 107416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liang, J.F.; Gao, J.Q.; Xu, X.L.; Yu, F.H. High nitrogen uptake and utilization contribute to the dominance of invasive Spartina alterniflora over native Phragmites australis. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 57, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.Q.; Feagin, R.A.; Innocenti, R.A.; Hu, B.B.; He, M.X.; Li, H.Y. Invasion and ecological effects of exotic smooth cordgrass Spartina alterniflora in China. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 143, 105670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Duan, X.J.; Li, P.X.; Wang, L.Q. Spatiotemporal intensification of net anthropogenic nitrogen input driven by human activities in China from 1990 to 2020. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K.M.; Hawkes, C.V. Soil precipitation legacies influence intraspecific plant-soil feedback. Ecology 2020, 101, e03142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuma, M.C.; Burgess, T.I.; Sapsford, S.J. Addressing variability and advancing methodological clarity in plant-soil feedback experiments. J. Plant Interact. 2025, 20, 2529228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, O.; Bezemer, T.M. Abiotic and biotic soil legacy effects of plant diversity on plant performance. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, e03142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Pennings, S.C. Mechanisms mediating plant distributions across estuarine landscapes in a low-latitude tidal estuary. Ecology 2012, 93, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Dastogeer, K.M.G.; Carrillo, Y.; Nielsen, U.N. Climate change-driven shifts in plant-soil feedbacks: A meta-analysis. Ecol. Process. 2022, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.A.; Klironomos, J. Mechanisms of plant-soil feedback: Interactions among biotic and abiotic drivers. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A.C.; Lambrinos, J.G.; Grosholz, E.D. Nitrogen inputs promote the spread of an invasive marsh grass. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1886–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, W.; Xia, L.; Qiao, Y.J.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, X.L.; An, S.Q. Nitrogen-enriched eutrophication promotes the invasion of Spartina alterniflora in coastal China. Clean Soil. Air Water 2015, 43, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, B.S.; Xie, T.; Wang, Q.; Yan, J.G. Effect of coastal eutrophication on growth and physiology of Spartina alterniflora Loisel. Phys. Chem. Earth 2018, 103, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, M.; Sathish, M.; Kiran, R.; Mushtaq, A.; Baazeem, A.; Hasnain, A.; Hakim, F.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Mubeen, M.; Iftikhar, Y.; et al. Plant nitrogen metabolism: Balancing resilience to nutritional stress and abiotic challenges. Phyton Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Shao, X.X.; Yuan, H.J.; Liu, E.J.; Wu, M. Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus stoichiometry and plant growth strategy as related to land-use in Hangzhou Bay coastal wetland, China. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 946949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, H.; Cai, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yao, Y.H.; An, S.Q. Nitrogen uptake and use efficiency of invasive Spartina alterniflora and native Phragmites australis: Effect of nitrogen supply. Clean Soil. Air Water 2015, 43, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.T.; Gao, D.Z.; Zhang, J.B.; Müller, C.; Li, X.F.; Zheng, Y.L.; Dong, H.P.; Yin, G.Y.; Han, P.; Liang, X.; et al. Invasive Spartina alterniflora accelerates soil gross nitrogen transformations to optimize its nitrogen acquisition in an estuarine and coastal wetland of China. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2022, 174, 108835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, C.H.; He, Q.; Qiu, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, B.; Nie, M. Phenotypic plasticity of light use favors a plant invader in nitrogen-enriched ecosystems. Ecology 2022, 103, e3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, D.; Pivato, B.; Bru, D.; Busset, H.; Deau, F.; Faivre, C.; Matejicek, A.; Strbik, F.; Philippot, L.; Mougel, C. Plant traits related to nitrogen uptake influence plant-microbe competition. Ecology 2015, 96, 2300–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Begines, J.; Avila, J.M.; García, L.V.; Gómez-Aparicio, L. Disentangling the role of oomycete soil pathogens as drivers of plant-soil feedbacks. Ecology 2021, 102, e03430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, L.A.; Mortensen, B.; Sullivan, L.; Harpole, W.S. Soil microbial community structure and function in non-target and plant-influenced soils respond similarly to nitrogen enrichment. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2025, 207, 109830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, X.L. Competition between roots and microorganisms for nitrogen: Mechanisms and ecological relevance. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsaeth, A.; Molstad, L.; Bakken, L.R. Modelling the competition for nitrogen between plants and microflora as a function of soil heterogeneity. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.B.; Karp, M.A. Soil pathogen communities associated with native and non-native Phragmites australis populations in freshwater wetlands. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 5254–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.M.; Oduor, A.M.O.; Yu, F.H.; Dong, M. A native parasitic plant and soil microorganisms facilitate a native plant co-occurrence with an invasive plant. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 8652–8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, V.M.; Kotanen, P.M. Development of negative soil feedback by an invasive plant near the northern limit of its invaded range. Plant Ecol. 2023, 224, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijjer, S.; Rogers, W.E.; Siemann, E. Negative plant-soil feedbacks may limit persistence of an invasive tree due to rapid accumulation of soil pathogens. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 2621–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, G.R.; Swamy, S.L.; Mishra, A.; Thakur, T.K. Effect of seed source, light, and nitrogen levels on biomass and nutrient allocation pattern in seedlings of Pongamia pinnata. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 15005–15020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Cossani, C.M.; Sadras, V.O.; Yang, Q.C.; Wang, Z. The interaction between nitrogen supply and light quality modulates plant growth and resource allocation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 864090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.F.; Yang, Y.H. Allometric biomass partitioning under nitrogen enrichment: Evidence from manipulative experiments around the world. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, A.C.A.; Evans, J.R.; Kaiser, B.N.; Millar, A.H.; Kariyawasam, B.C.; Atkin, O.K. Effect of N supply on the carbon economy of barley when accounting for plant size. Funct. Plant Biol. 2020, 47, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Zhan, J.; Ning, Z.Y.; Li, Y.L. Influence of nitrogen inputs on biomass allocation strategies of dominant plant species in sandy ecosystems. J. Arid. Land 2025, 17, 1118–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Frey, B.; Li, D.T.; Liu, X.Y.; Chen, C.R.; Liu, Y.N.; Zhang, R.T.; Sui, X.; Li, M.H. Effects of organic nitrogen addition on soil microbial community assembly patterns in the Sanjiang Plain wetlands, northeastern China. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2024, 204, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.Y.; Song, Y.Y.; Li, M.T.; Gong, C.; Liu, Z.D.; Yuan, J.B.; Li, X.Y.; Song, C.C. Ammonia nitrogen and dissolved organic carbon regulate soil microbial gene abundances and enzyme activities in wetlands under different vegetation types. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2024, 196, 105310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P.; Morrison, S.A.; Bonkowski, M.; Bardgett, R.D. Nitrogen enrichment modifies plant community structure via changes to plant-soil feedback. Oecologia 2008, 157, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.Y.; Liu, Z.D.; Song, Y.Y.; Wang, X.W.; Yuan, J.B.; Li, M.T.; Lou, Y.J.; Gao, Z.L.; Song, C.C. Soil microbial functional diversity is primarily affected by soil nitrogen, salinity and alkalinity in wetland ecosystem. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2024, 199, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrone, A.; Yang, Y.G.; Yadav, P.; Weber, K.A.; Russo, S.E. Nutrient and microbiome-mediated plant-soil feedback in domesticated and wild andropogoneae: Implications for agroecosystems. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.L.; Berg, B.; Gu, W.P.; Wang, Z.W.; Sun, T. Effects of different forms of nitrogen addition on microbial extracellular enzyme activity in temperate grassland soil. Ecol. Process. 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.H.; Sui, X.; Liu, Y.N.; Yang, L.B.; Zhang, R.T. Effect of nitrogen addition on the carbon metabolism of soil microorganisms in a Calamagrostis angustifolia wetland of the Sanjiang Plain, northeastern China. Ann. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Fornara, D.A.; Li, W.; Ni, X.Y.; Peng, Y.; Liao, S.; Tan, S.Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Wu, F.Z.; Yang, Y.S. Nitrogen addition affects plant biomass allocation but not allometric relationships among different organs across the globe. J. Plant Ecol. 2021, 14, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Y.; Fanselow, N.; Dittert, K.; Taube, F.; Lin, S. Response of primary production and biomass allocation to nitrogen and water supplementation along a grazing intensity gradient in semiarid grassland. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 63, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zuo, X.A.; Zhao, X.Y.; Ma, J.X.; Medina-Roldán, E. Effects of rainfall manipulation and nitrogen addition on plant biomass allocation in a semiarid sandy grassland. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.W.; Guo, X.; Skálová, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.F.; Li, M.Y.; Guo, W.H. Shift in the effects of invasive soil legacy on subsequent native and invasive trees driven by nitrogen deposition. Neobiota 2024, 93, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Yao, X.W.; Jia, Z.J.; Zhu, L.Z.; Zheng, P.; Kartal, B.; Hu, B.L. Nitrogen input promotes denitrifying methanotrophs’ abundance and contribution to methane emission reduction in coastal wetland and paddy soil. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 302, 119090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.Y.; Huang, J.X.; Lu, M.; Xu, X.; Li, X.C.; Zhang, Q.; Xin, F.F.; Zhou, C.H.; Zhang, X.; Nie, M.; et al. Nutrient enrichment undermines invasion resistance to Spartina alterniflora in a saltmarsh: Insights from modern coexistence theory. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 2472–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Chen, X.P.; Nie, M.; Fang, S.B.; Tang, B.P.; Quan, Z.X.; Li, B.; Fang, C.M. Effects of Spartina alterniflora invasion on the abundance, diversity, and community structure of sulfate reducing bacteria along a successional gradient of coastal salt marshes in China. Wetlands 2017, 37, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.Z.; Chen, Q.Q.; Qiu, Y.F.; Xie, R.R.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.B.; Han, Y.H. Spartina alterniflora invasion altered phosphorus retention and microbial phosphate solubilization of the Minjiang estuary wetland in southeastern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yu, Z.W.; Wang, M.L. Effects of Spartina alterniflora invasion on macrobenthic faunal community in different habitats of a mangrove wetland in Zhanjiang, South China. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 66, 103148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Properties | Sterilized Soil (SS) | Inoculated Soil (IS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N0 | N1 | N2 | N0 | N1 | N2 | |

| Water content (%) | 35.37 ± 0.07 a | 35.52 ± 0.06 a | 35.53 ± 0.07 a | 35.51 ± 0.03 a | 35.39 ± 0.11 a | 35.53 ± 0.04 a |

| Salinity (PSU) | 20.10 ± 0.12 a | 20.22 ± 0.21 a | 20.15 ± 0.23 a | 20.08 ± 0.18 a | 20.29 ± 0.19 a | 20.22 ± 0.03 a |

| pH | 7.53 ± 0.02 a | 7.45 ± 0.03 b | 7.39 ± 0.02 c | 7.54 ± 0.02 a | 7.45 ± 0.02 b | 7.36 ± 0.02 c |

| Organic carbon content (g/kg) | 15.37 ± 0.14 a | 15.38 ± 0.13 a | 15.33 ± 0.05 a | 15.40 ± 0.14 a | 15.50 ± 0.16 a | 15.46 ± 0.18 a |

| Total nitrogen content (mg/kg) | 61.51 ± 0.09 c | 70.52 ± 0.18 b | 79.57 ± 0.25 a | 61.34 ± 0.22 c | 70.60 ± 0.23 b | 79.58 ± 0.21 a |

| Available phosphorus content (mg/kg) | 15.56 ± 0.23 c | 16.68 ± 0.17 b | 17.61 ± 0.29 a | 15.80 ± 0.13 c | 16.72 ± 0.19 b | 17.81 ± 0.14 a |

| Source of Variance | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height of S. alterniflora | |||

| Soil condition | 1, 24 | 69.993 | <0.001 *** |

| Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 151.828 | <0.001 *** |

| Soil condition × Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 4.860 | 0.017 * |

| Basal stem diameter of S. alterniflora | |||

| Soil condition | 1, 24 | 43.835 | <0.001 *** |

| Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 130.672 | <0.001 *** |

| Soil condition × Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 3.589 | 0.043 * |

| Number of leaves of S. alterniflora | |||

| Soil condition | 1, 24 | 34.426 | <0.001 *** |

| Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 55.181 | <0.001 *** |

| Soil condition × Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 3.835 | 0.036 * |

| Aboveground biomass of S. alterniflora | |||

| Soil condition | 1, 24 | 32.053 | <0.001 *** |

| Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 25.816 | <0.001 *** |

| Soil condition × Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 8.763 | 0.002 ** |

| Belowground biomass of S. alterniflora | |||

| Soil condition | 1, 24 | 7.791 | 0.010 * |

| Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 12.765 | <0.001 *** |

| Soil condition × Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 1.097 | 0.350 |

| Total biomass of S. alterniflora | |||

| Soil condition | 1, 24 | 22.548 | <0.001 *** |

| Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 10.232 | <0.001 *** |

| Soil condition × Nitrogen addition | 2, 24 | 3.618 | 0.042 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, C.; Xie, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, H. Nitrogen Addition Reduces Negative Plant-Soil Feedback in Invasive Spartina alterniflora: Preliminary Findings from a Mesocosm Experiment. Agronomy 2026, 16, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010086

Wang Y, Li N, Zhang Y, Guo C, Xie L, Li Y, Guo H. Nitrogen Addition Reduces Negative Plant-Soil Feedback in Invasive Spartina alterniflora: Preliminary Findings from a Mesocosm Experiment. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yinhua, Ningning Li, Yuxin Zhang, Changcheng Guo, Lina Xie, Yifan Li, and Hongyu Guo. 2026. "Nitrogen Addition Reduces Negative Plant-Soil Feedback in Invasive Spartina alterniflora: Preliminary Findings from a Mesocosm Experiment" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010086

APA StyleWang, Y., Li, N., Zhang, Y., Guo, C., Xie, L., Li, Y., & Guo, H. (2026). Nitrogen Addition Reduces Negative Plant-Soil Feedback in Invasive Spartina alterniflora: Preliminary Findings from a Mesocosm Experiment. Agronomy, 16(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010086