Environmental Stress Tolerance and Intraspecific Variability in Cortaderia selloana: Implications for Invasion Risk in Mediterranean Wetlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

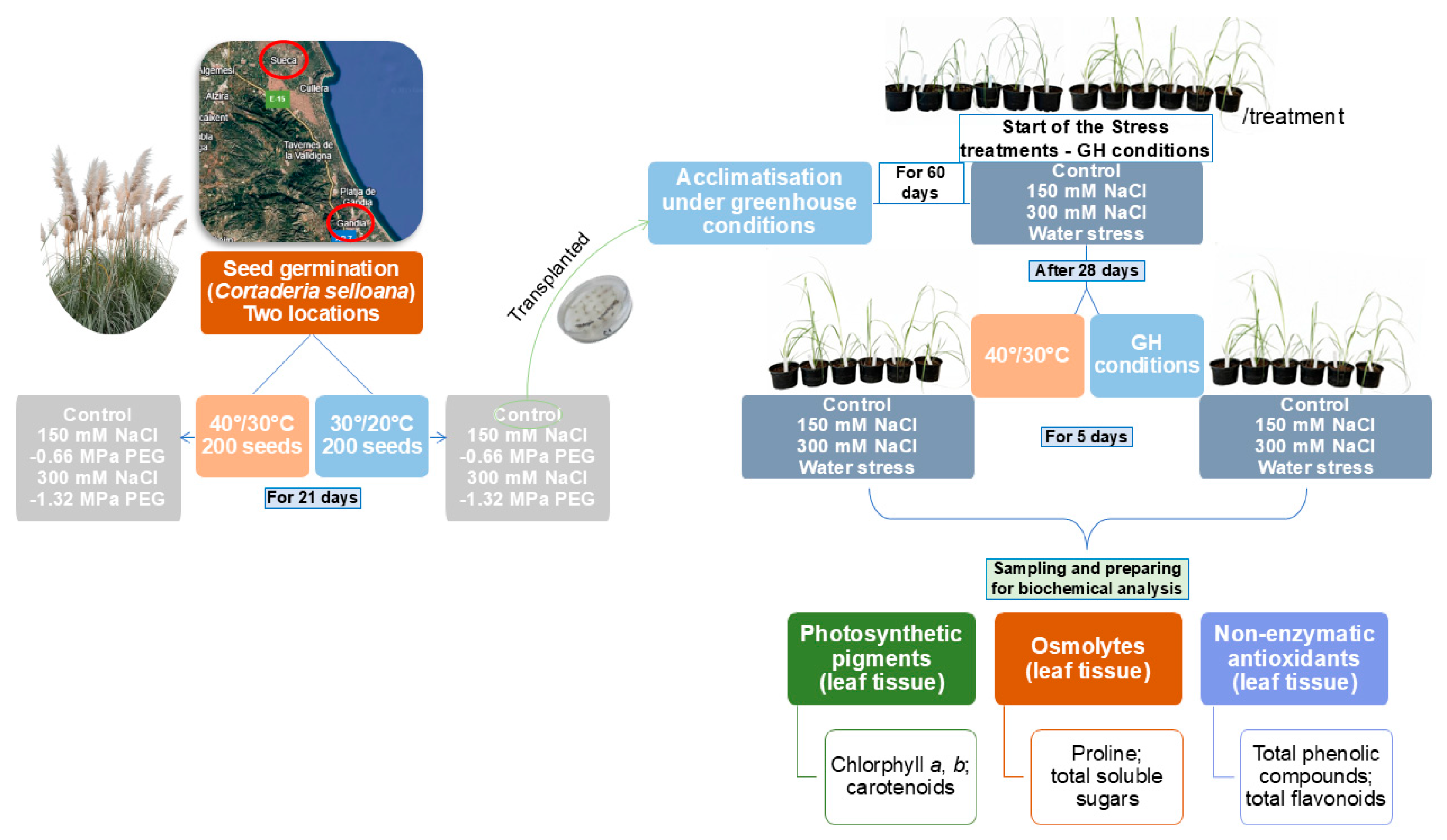

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin of Plant Material, Characterisation of the Seed Sampling Areas and Experimental Design

2.2. Seed Germination

2.3. Plant Growth and Stress Treatments

2.4. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments

2.5. Quantification of Osmolytes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

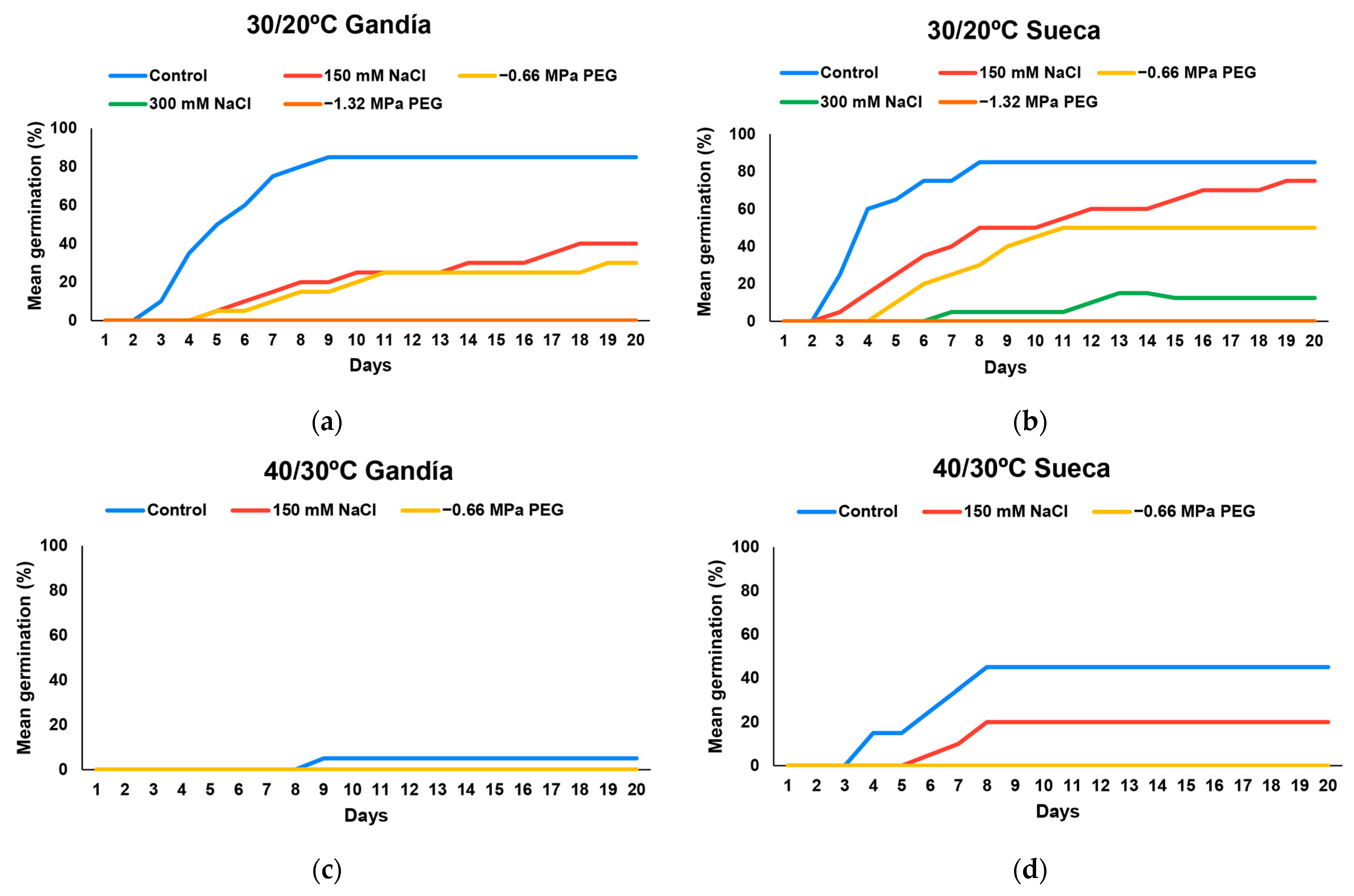

3.1. Seed Germination

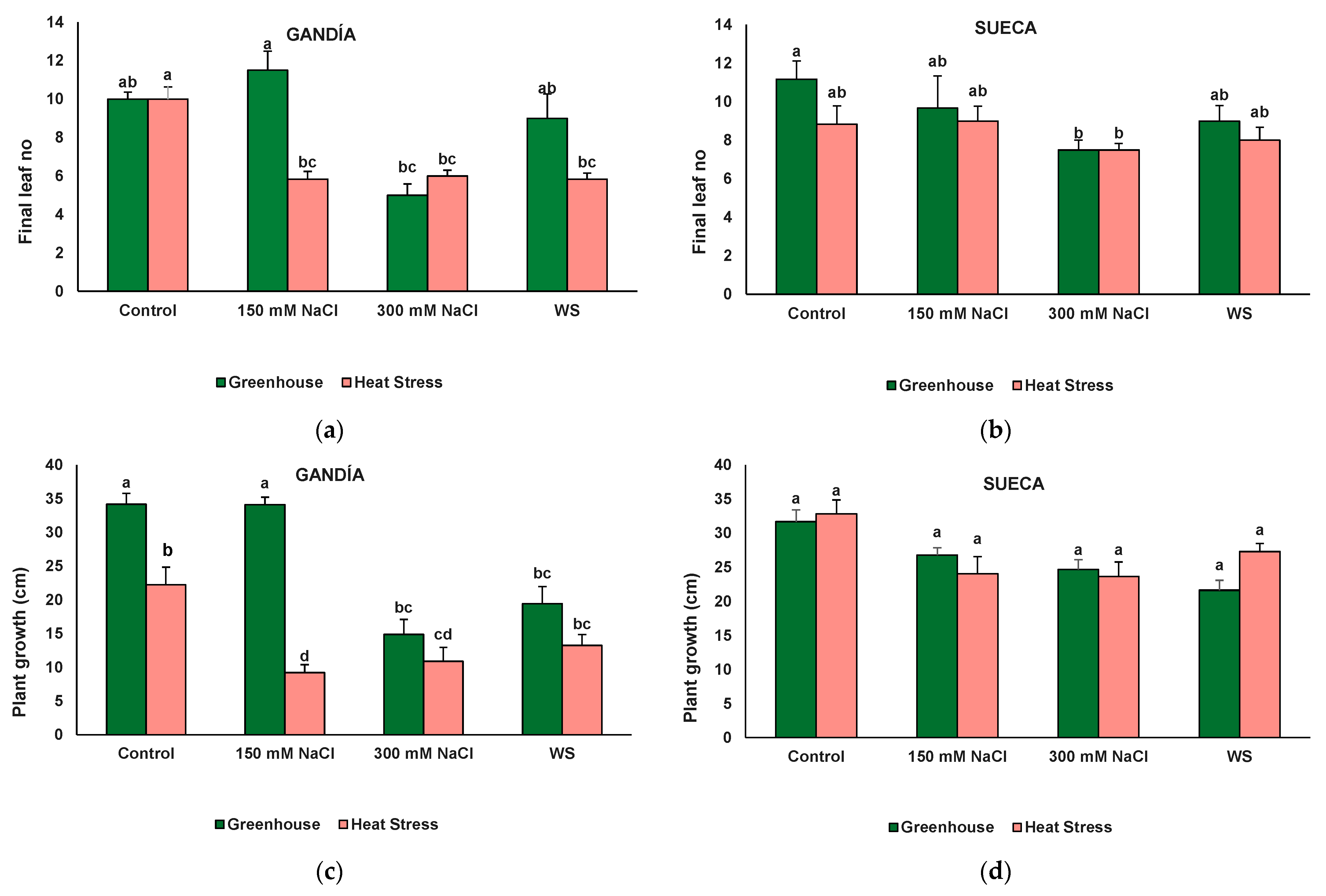

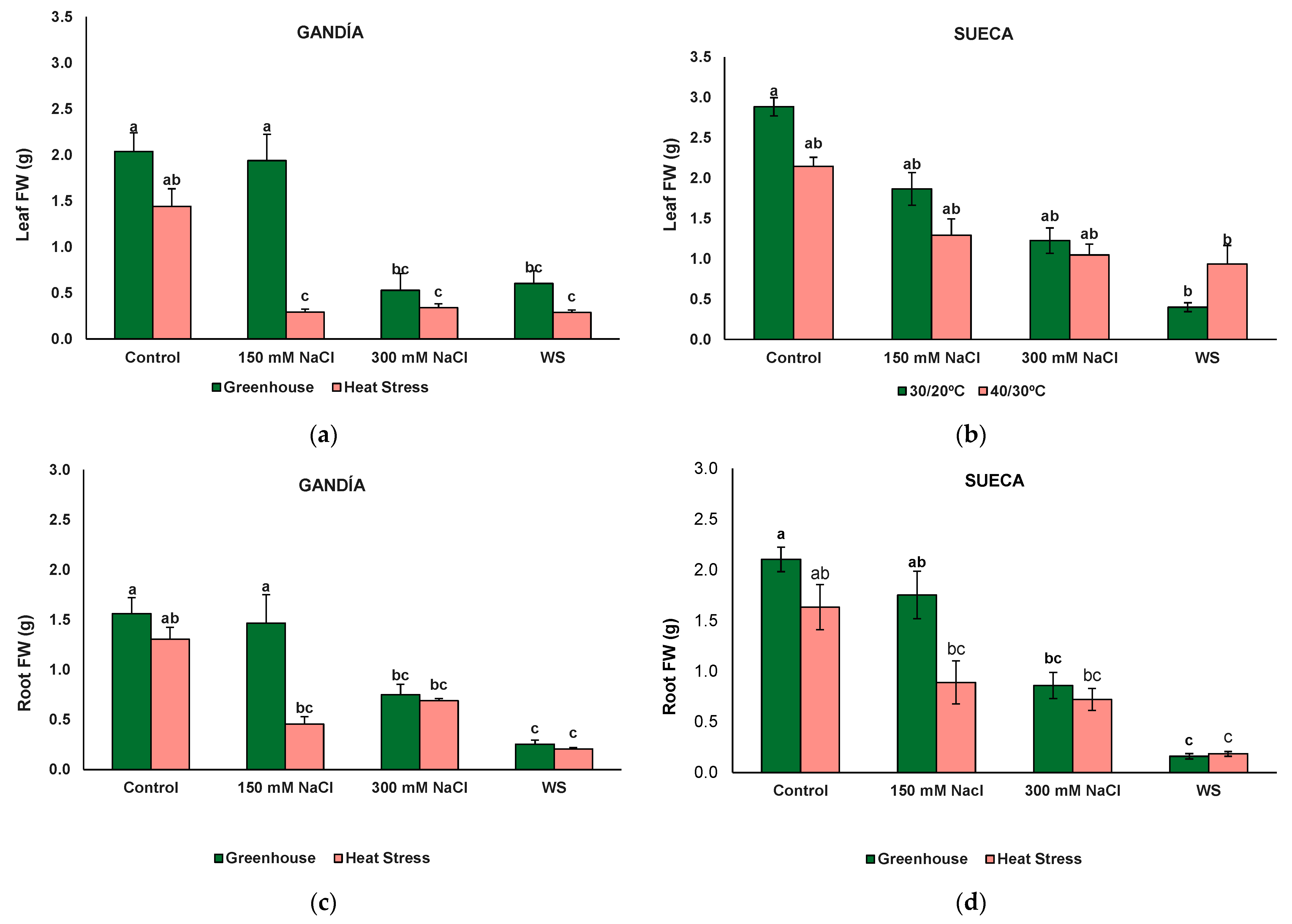

3.2. Plant Growth

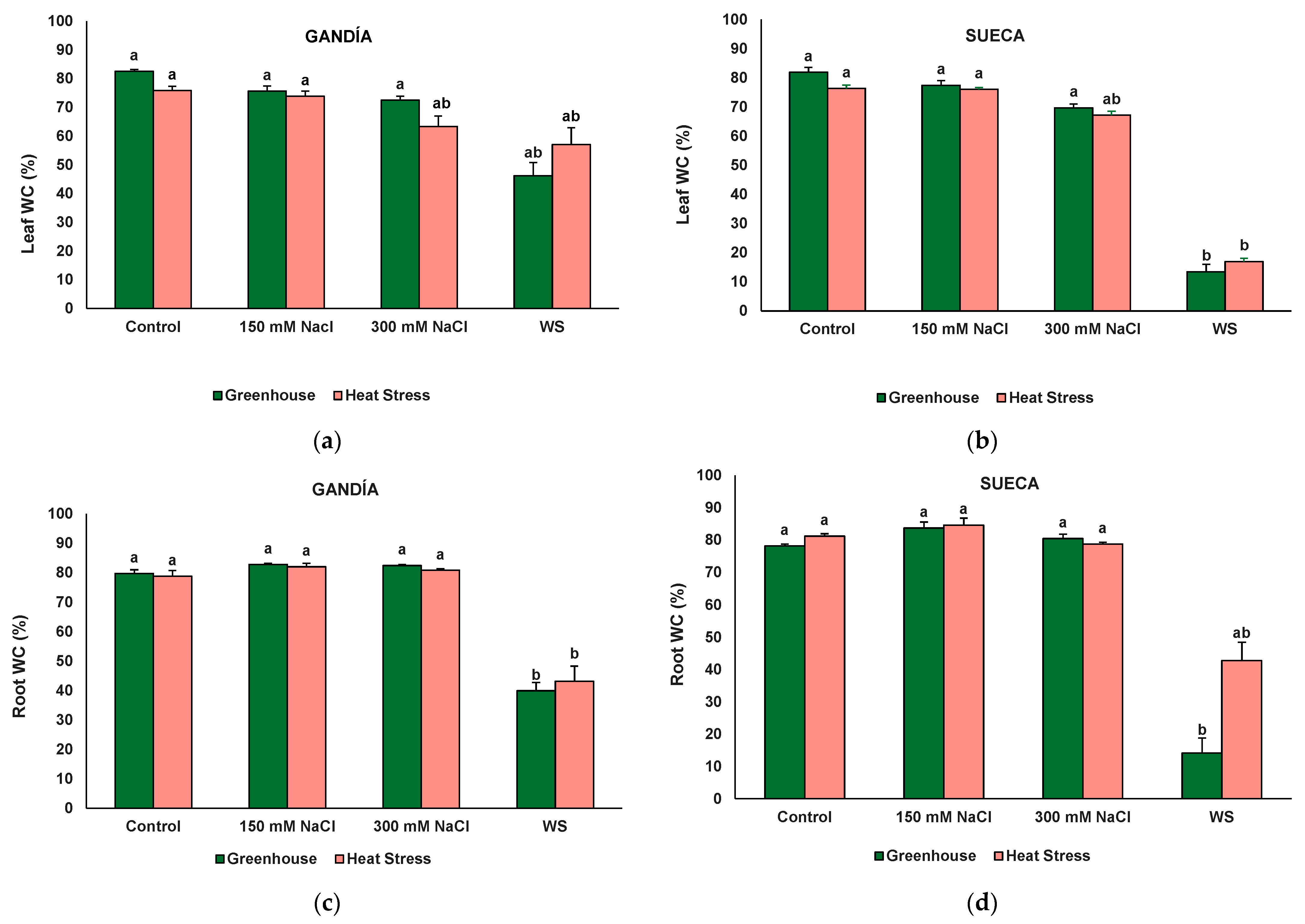

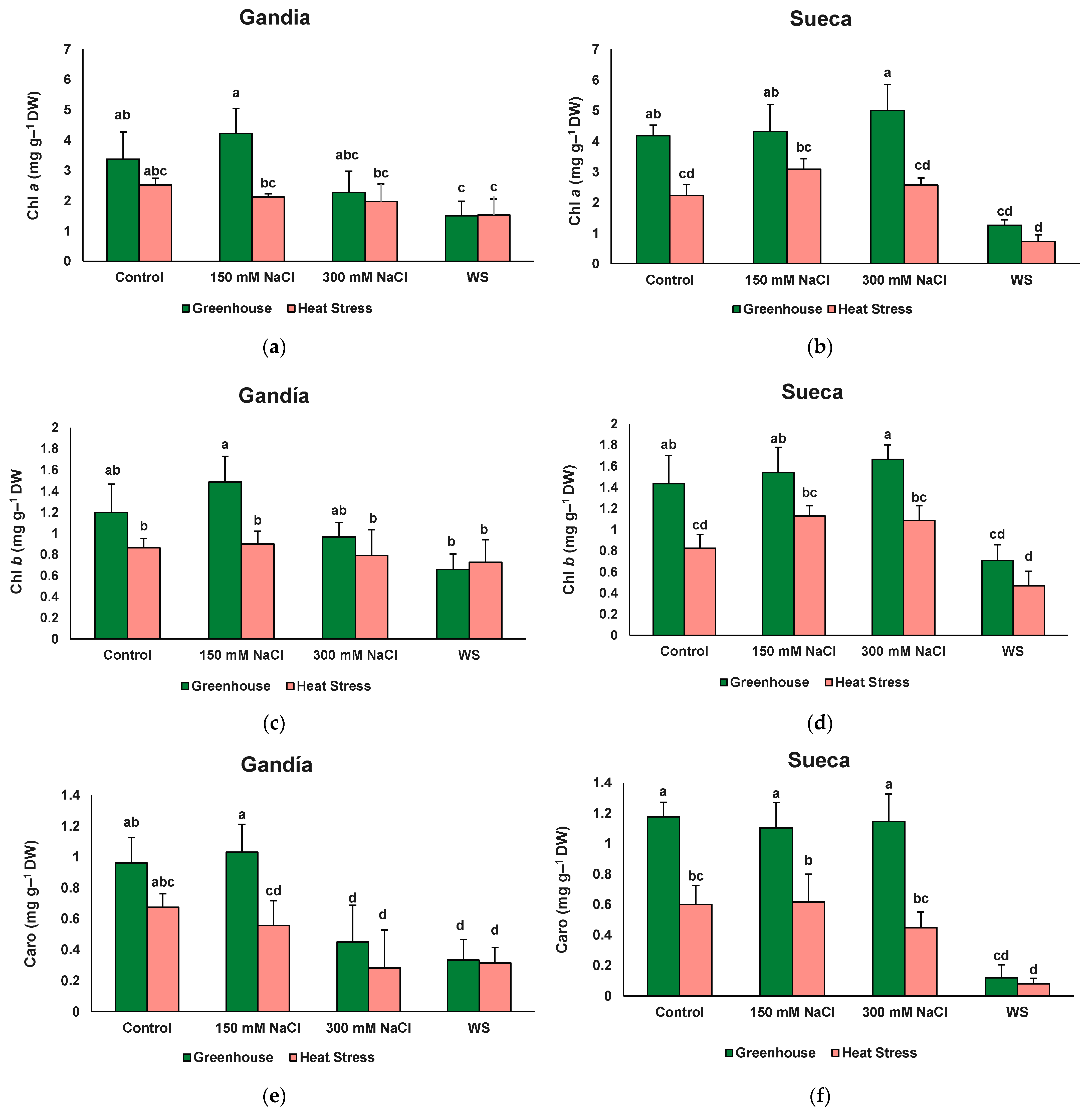

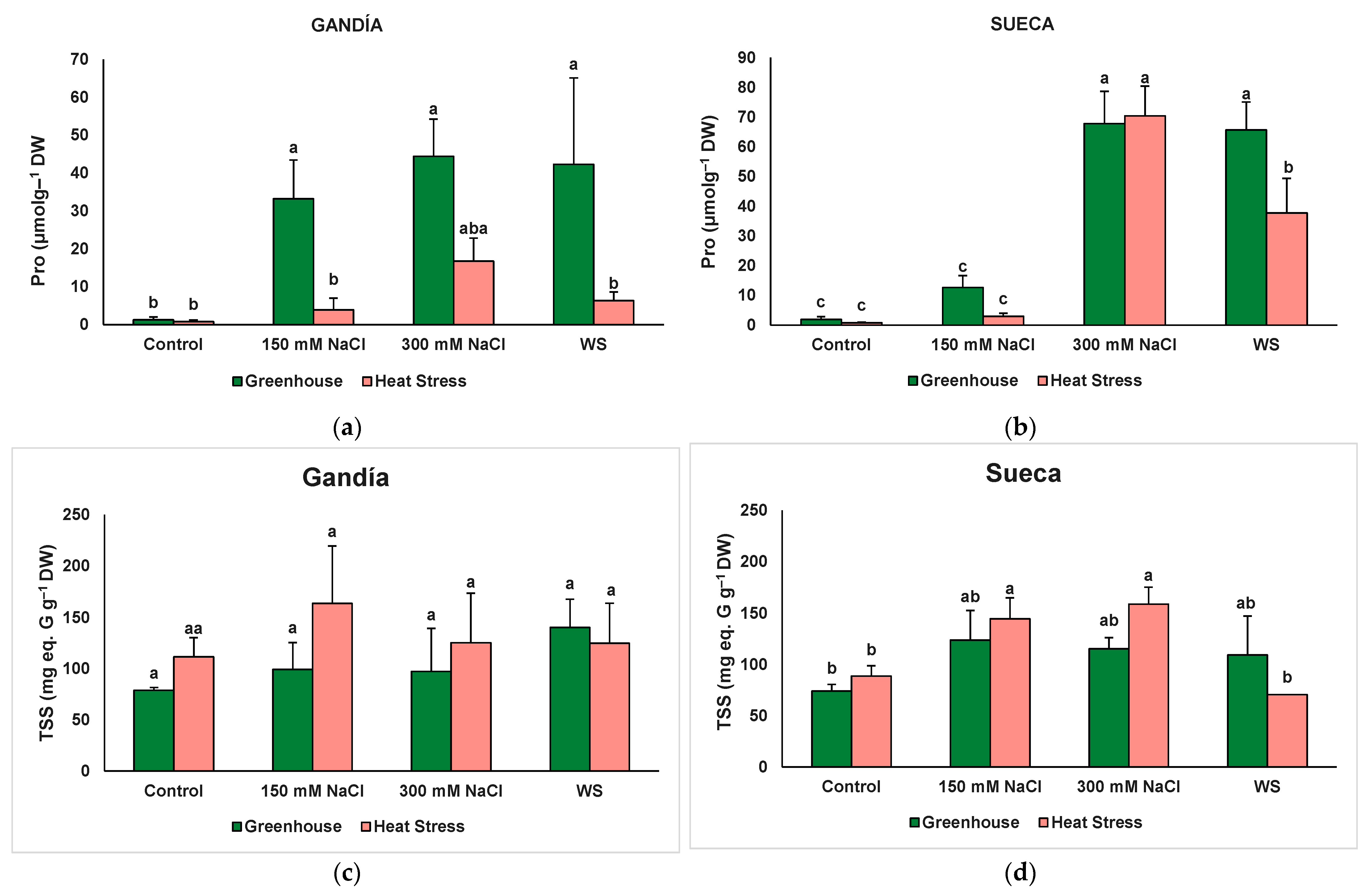

3.3. Biochemical Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Germination Responses to Abiotic Stress

4.2. Growth Responses to Salt, Water, and Temperature Stress

4.3. Biochemical Responses to Salt, Water, and Temperature Stress

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dukes, J.S.; Mooney, H.A. Does global change increase the success of biological invaders? Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syngkli, R.B.; Rai, P.K.; Lalnuntluanga. Expanding horizon of invasive alien plants under the interacting effects of global climate change: Multifaceted impacts and management prospects. Clim. Change Ecol. 2025, 9, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chown, S.L.; Hodgins, K.A.; Griffin, P.C.; Oakeshott, J.G.; Byrne, M.; Hoffmann, A.A. Biological invasions, climate change and genomics. Evol. Appl. 2015, 8, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrinos, J.G. The impact of the invasive alien grass Cortaderia jubata (Lemoine) Stapf on an endangered Mediterranean-type shrubland in California. Divers. Distrib. 2000, 6, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liendo, D.; Campos, J.A.; Gandarillas, A. Cortaderia selloana, an example of aggressive invaders that affect human health, yet to be included in binding international invasive catalogues. NeoBiota 2023, 89, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro-Lobo, A.; Andrade, B.O.; Canavan, K.; Ervin, G.N.; Essl, F.; Fernández-Pascual, E.; Follak, S.; Richardson, D.M.; Moles, A.; Visser, V.; et al. Monographs on invasive plants in Europe N° 8: Cortaderia selloana (Schult. & Schult. f.) Asch. & Graebn. Bot. Lett. 2024, 17, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrinos, J.G. How interactions between ecology and evolution influence contemporary invasion dynamics. Ecology 2004, 85, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, R. Cortaderia selloana Invasion in the Mediterranean Region: Invasiveness and Ecosystem Invasibility. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pausas, J.G.; Lloret, F.; Vilà, M. Simulating the effects of different disturbance regimes on Cortaderia selloana invasion. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 128, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, R.; Vilà, M.; Gesti, J.; Serrasolses, I. Neighbourhood association of Cortaderia selloana invasion, soil properties and plant community structure in Mediterranean coastal grasslands. Acta Oecol. 2006, 29, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro-Lobo, A.; Alonso-Zaldívar, H.; Sagrera, S.J.M.; del Alba, C.E.; Fernández-Pascual, E.; González-García, V.; Jiménez-Alfaro, B. Regeneration niche of Cortaderia selloana in an invaded region: Flower predation, environmental stress, and transgenerational effects. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltoro-Torró, V. Ficha de la Especie (Cortaderia selloana). Banco de Datos de Biodiversidad de la Comunitat Valenciana. Available online: https://bddb.gva.es/bancodedatos/extendida/ficha.aspx?Param=ygUx0MrLnTaUpAuWYXTYHeo0daenXHpUPxERyTmI8Gm4cP0JwfbgAkSolv_vzw9kJSXFDRjGiklX67SOG5cSNUeIaW4wsTnKQqjqdQNNkOk (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Pérez, A.; Ruiz, B.; Fuente, E.; Calvo, L.F.; Paniagua, S. Pyrolysis technology for Cortaderia selloana invasive species. Prospects in the biomass energy sector. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiya, M.A.; Dominic, C.D.M.; Nandakumar, N.; Joseph, R.; George, K.E. Isolation and characterization of fibrillar nanosilica of floral origin: Cortaderia selloana flowers as the silica source. Silicon 2022, 4, 4139–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaee, M.M.; Zakerinia, M.; Farasati, M. Performance evaluation of vetiver and pampas plants in reducing the hazardous ions of treated municipal wastewater for agricultural irrigation water use. Water Pract. Technol. 2022, 17, 1002–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, M.N.; Pinto, D.; Basto, M.C.; Vasconcelos, T.S. Role of natural attenuation, phytoremediation and hybrid technologies in the remediation of a refinery soil with old/recent petroleum hydrocarbons contamination. Environ. Technol. 2012, 33, 2097–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.A.; Herrera, M.; Biurrun, I.; Loidi, J. The role of alien plants in the natural coastal vegetation in central-northern Spain. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 2275–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GISD (Global Invasive Species Database). Species Profile: Cortaderia selloana. Available online: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/speciesname/Cortaderia+selloana (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Sanz Elorza, M.; Dana Sánchez, E.D.; Sobrino Vesperinas, E. Atlas de las Plantas Alóctonas Invasoras en España; Dirección General para la Biodiversidad: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MITECO (Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico). Estrategia de Gestión, Control y Posible Erradicación del Plumero de la Pampa (Cortaderia selloana) y Otras Especies de Cortaderia. Comisión Estatal para el Patrimonio Natural y la Biodiversidad. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/publicaciones/pbl_fauna_flora_estrategia_cortaderia.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- DiTomaso, J.M.; Healy, E.; Bell, C.E.; Drewitz, J.; Stanton, A. Pampasgrass and Jubatagrass Threaten California Coastal Habitats. WRIC Leaflet 99-1 01/1999 (Edited 01/2010), University of California. 1999. Available online: https://ucdavis.app.box.com/s/dp1cymjomzidc3ldrijii0a4p32t4qoj/file/2055789640386 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Moreno, T.; Fagúndez, J. Historia de una invasión: Presencia y representatividad de Cortaderia selloana en los herbarios ibéricos. Ecosistemas 2025, 34, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Guo, Z.; Sun, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, F.; Chen, Y. Role of proline in regulating turfgrass tolerance to abiotic stress. Grass Res. 2023, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dias, M.C.; Freitas, H. Drought and salinity stress responses and microbe-induced tolerance in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 591911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Du, Y.; Li, Z. Phytohormonal homeostasis, chloroplast stability, and heat shock transcription pathways related to the adaptability of creeping bentgrass species to heat stress. Protoplasma 2025, 262, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-L.; Chen, J.-H.; He, N.-Y.; Guo, F.-Q. Metabolic reprogramming in chloroplasts under heat stress in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y. Antioxidant defense system in plants: Reactive oxygen species production, signaling, and scavenging during abiotic stress-induced oxidative damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving abiotic stress tolerance in plants through antioxidative defence mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, R.; Vilà, M. Cortaderia selloana seed germination under different ecological conditions. Acta Oecol. 2008, 33, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagúndez, J.; Sánchez, A. High variability and multiple trade-offs in reproduction and growth of the invasive grass Cortaderia selloana after cutting. Weed Res. 2024, 64, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, G.; Dettori, C.A.; Mascia, F.; Meloni, F.; Podda, L. Assessing the potential invasiveness of Cortaderia selloana in Sardinian wetlands through seed germination study. Plant Biosyst. 2010, 144, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company, T.; Soriano, P.; Estrelles, E.; Mayoral, O. Seed bank longevity and germination ecology of invasive and native grass species from Mediterranean wetlands. Folia Geobot. 2019, 54, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, D.M.; Estrelles, E.; Al Hassan, M.; Soriano, P.; Sestras, R.E.; Boscaiu, M.; Sestras, A.F.; Vicente, O. Effect of water deficit on germination, growth and biochemical responses of four potentially invasive ornamental grass species. Plants 2023, 12, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doménech-Carbó, A.; Montoya, N.; Soriano, P.; Estrelles, E. An electrochemical analysis suggests role of gynodioecy in adaptation to stress in Cortaderia selloana. Curr. Plant Biol. 2018, 16, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.E.; DiTomaso, J.M. Growth response of Cortaderia selloana and Cortaderia jubata (Poaceae) seedlings to temperature, light, and water. Madroño 2004, 51, 31–321. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41425552 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Domènech, R.; Vilà, M. Response of the invader Cortaderia selloana and two coexisting natives to competition and water stress. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioria, M.; Hulme, P.E.; Richardson, D.M.; Pyšek, P. Why are invasive plants successful? Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 635–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, A.R.; Brown, C.S.; Espeland, E.K.; McKay, J.K.; Meimberg, H.; Rice, K.J. SYNTHESIS: The role of adaptive trans-generational plasticity in biological invasions of plants. Evol. Appl. 2010, 3, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioria, M.; Pyšek, P. Early bird catches the worm: Germination as a critical step in plant invasion. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 1055–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGME (Instituto Geológico y Minero de España). Gandía [Mapa]. 1:50.000. Mapa Geológico de España 1:50.000, Hoja 796. Available online: https://info.igme.es/cartografiadigital/geologica/Magna50Hoja.aspx?Id=796&language=es (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- IGME (Instituto Geológico y Minero de España). Sueca [Mapa]. 1:50.000. Mapa Geológico de España 1:50.000, Hoja 747. Available online: https://info.igme.es/cartografiadigital/geologica/Magna50Hoja.aspx?Id=747&language=es (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Ben-Gal, A.; Borochov-Neori, H.; Yermiyahu, U.; Shani, U. Is osmotic potential a more appropriate property than electrical conductivity for evaluating whole-plant response to salinity? Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 65, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.A.; Roberts, E.H. The quantification of aging and survival in orthodox seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 1981, 9, 373–409. [Google Scholar]

- Mircea, D.-M.; González-Orenga, S.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.; Díaz-Tielas, C.; Ferrer-Gallego, P.P.; Mir, R.; Prohens, J.; Vicente, O.; Boscaiu, M. Tolerance mechanisms and metabolomic profiling of Kosteletzkya pentacarpos in saline environments. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Saavedra, M.; Gramazio, P.; Vilanova, S.; Mircea, D.M.; Ruiz-González, M.X.; Vicente, O.; Prohens, J.; Plazas, M. Introgressed eggplant lines with the wild Solanum incanum evaluated under drought stress conditions. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 26, 2203–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricco, M.V.; Khemakem, S.; Gago, J.; Quintanilla, L.G.; Íñiguez, C.; Flexas, J.; Gulías, J.; Clemente-Moreno, M.J. Photosynthetic and biochemical responses to multiple abiotic stresses in Deschampsia antarctica, Poa pratensis, and Triticum aestivum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 237, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, D.-M.; Li, R.; Blasco Giménez, L.; Vicente, O.; Sestras, A.F.; Sestras, R.E.; Boscaiu, M.; Mir, R. Salt and water stress tolerance in Ipomoea purpurea and Ipomoea tricolor, two ornamentals with invasive potential. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, U.; Morris, W.L.; Ducreux, L.J.M.; Yavuz, C.; Asim, A.; Tindas, I.; Campbell, R.; Morris, J.A.; Verrall, S.R.; Hedley, P.E.; et al. Physiological, biochemical, and transcriptional responses to single and combined abiotic stress in stress-tolerant and stress-sensitive potato genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983, 11, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, O.; Boscaiu, M.; Naranjo, M.Á.; Estrelles, E.; Bellés, J.M.; Soriano, P. Responses to salt stress in the halophyte Plantago crassifolia (Plantaginaceae). J. Arid Environ. 2004, 58, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blainski, A.; Lopes, G.; Mello, J. Application and analysis of the Folin Ciocalteu method for the determination of the total phenolic content from Limonium brasiliense L. Molecules 2013, 18, 6852–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nešić, M.; Obratov-Petković, D.; Skočajić, D.; Bjedov, I.; Čule, N. Factors affecting seed germination of the invasive species Symphyotrichum lanceolatum and their implication for invasion success. Plants 2022, 11, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura-Mas, S.; Lloret, F. Wind effects on dispersal patterns of the invasive alien Cortaderia selloana in Mediterranean wetlands. Acta Oecol. 2005, 27, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, M.; Thompson, K. The Ecology of Seeds; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Extreme temperature responses, oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in plants. In Abiotic Stress—Plant Responses and Applications in Agriculture; Vhadati, K., Leslie, C., Eds.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2013; pp. 169–205. [Google Scholar]

- Essemine, J.; Ammar, S.; Bouzid, S. Impact of heat stress on germination and growth in higher plants: Physiological, biochemical and molecular repercussions and mechanisms of defence. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 10, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrinos, J.G. The expansion history of a sexual and asexual species of Cortaderia in California, USA. J. Ecol. 2001, 89, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Farooq, M.; Hussain, I.; Rasheed, R.; Galani, S. Responses and management of heat stress in plants. In Environmental Adaptations and Stress Tolerance of Plants in the Era of Climate Change; Ahmad, P., Prasad, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, L.F. Maternal effects provide phenotypic adaptation to local environmental conditions. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pascual, E.; Mattana, E.; Pritchard, H.W. Seeds of future past: Climate change and the thermal memory of plant reproductive traits. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mafakheri, A.; Siosemardeh, A.F.; Bahramnejad, B.; Struik, P.C.; Sohrabi, Y. Effect of drought stress on yield, proline and chlorophyll contents in three chickpea cultivars. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2010, 4, 580–585. [Google Scholar]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Ahmadi, J.; Mehrabi, A.A.; Etminan, A.; Moghaddam, M.; Siddique, K.H.M. Physiological responses to drought stress in wild relatives of wheat: Implications for wheat improvement. Acta Physiol. Plant 2017, 39, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteoliva, M.I.; Guzzo, M.C.; Posada, G.A. Breeding for drought tolerance by monitoring chlorophyll content. Gene Technol. 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Cires, E.; Álvarez Rafael, D.; González-Toral, C.; Cuesta, C. A preliminary assessment of the genetic structure of the invasive plant Cortaderia selloana (Poaceae) in the Iberian Peninsula. Biologia 2022, 77, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeselmani, M.; Deshmukh, P.S.; Chinnusamy, V. Effects of prolonged high temperature stress on respiration, photosynthesis and gene expression in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties differing in their thermotolerance. Plant Stress 2012, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Suravajhala, P.; Rathnagiri, P.; Sreenivasulu, N. Intriguing role of proline in redox potential conferring high temperature stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 867531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, S.; Cabassa-Hourton, C.; Savouré, A.; Funck, D.; Forlani, G. Appropriate activity assays are crucial for the specific determination of proline dehydrogenase and pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase activities. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 602939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizhsky, L.; Liang, H.; Shuman, J.; Shulaev, V.; Davletova, S.; Mittler, R. When defense pathways collide. The response of Arabidopsis to a combination of drought and heat stress. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Sreenivasulu, N. Is proline accumulation per se correlated with stress tolerance or is proline homeostasis a more critical issue? Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, A.; Gelani, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Heat tolerance in plants: An overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | A | B | C | A × B | A × C | B × C | A × B × C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germination | 365.35 *** | 54.76 *** | 120.72 *** | 0.01 ns | 33.52 *** | 4.25 * | 10.34 *** |

| MGT | 79.23 *** | 2.14 ns | 12.72 *** | 3.45 ns | 14.78 *** | 1.94 ns | 9.82 *** |

| Seed Origin | Temperature | Treatment | Germination (%) | MGT (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gandía | 30/20 °C | Control | 77.50 ± 1.66 a | 5.50 ± 0.28 b |

| 150 mM NaCl | 25.00 ± 1.69 b | 11.54 ± 0.40 a | ||

| −0.66 MPa PEG | 25.00 ± 1.14 b | 9.82 ± 0.96 a | ||

| 300 mM NaCl | 0.00 | |||

| −1.32 MPa PEG | 0.00 | |||

| 40/30 °C | Control | 2.50 ± 0.86 c | 5.10 ± 1.10 b | |

| 150 mM NaCl | 0.00 | |||

| −0.66 MPa PEG | 0.00 | |||

| 300 mM NaCl | 0.00 | |||

| −1.32 MPa PEG | 0.00 | |||

| Sueca | 30/20 °C | Control | 80 ± 1.78 a | 4.66 ± 0.49 b |

| 150 mM NaCl | 55.00 ± 3.53 b | 7.14 ± 0.21 ab | ||

| −0.66 MPa PEG | 50.00 ± 3.56 bc | 7.74 ± 0.33 ab | ||

| 300 mM NaCl | 15.00 ± 0.44 d | 8.70 ± 0.82 a | ||

| −1.32 MPa PEG | 0.00 | |||

| 40/30 °C | Control | 45.00 ± 1.80 c | 6.06 ± 1.06 b | |

| 150 mM NaCl | 20.00 ± 1.87 d | 7.54 ± 0.54 ab | ||

| −0.66 MPa PEG | 0.00 | |||

| 300 mM NaCl | 0.00 | |||

| −1.32 MPa PEG | 0.00 |

| Parameter | A | B | C | A × B | A × C | B × C | A × B × C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial leaf no | 2.73 ns | 2.12 ns | 2.08 ns | 2.73 ns | 3.43 * | 1.52 ns | 1.62 ns |

| Final leaf no | 7.73 * | 0.04 * | 24.33 *** | 1.12 ns | 1.06 ns | 2.89 * | 2.80 * |

| Initial plant length | 2.17 ns | 8.92* | 0.27 ns | 0.81 ns | 1.66 ns | 0.04 ns | 0.70 ns |

| Final plant length | 12.04 ** | 24.41 *** | 5.19 ** | 12.34 ** | 4.94 * | 0.79 ns | 1.08 ns |

| Length Increase | 14.08 *** | 21.41 *** | 12.28 *** | 18.25 *** | 4.07 * | 1.49 ns | 1.78 ns |

| Leaf FW | 9.43 * | 12.87 ** | 21.54 *** | 2.20 ns | 3.18 * | 0.70 ns | 0.90 ns |

| Root FW | 14.41 *** | 4.73 * | 43.58 *** | 0.01 ns | 3.54 * | 1.58 ns | 0.36 ns |

| Leaf WC | 0.52 ns | 14.65 *** | 89.59 *** | 0.01 ns | 1.95 ns | 17.65 *** | 0.42 ns |

| Root WC | 4.90 * | 2.96 ns | 166.20 *** | 4.42 * | 5.09 * | 3.64 * | 2.84 * |

| Parameter | A | B | C | A × B | A × C | B × C | A × B × C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chl a | 2.32 ns | 13.52 *** | 8.33 *** | 1.29 ns | 1.75 ns | 0.87 ns | 1.03 ns |

| Chl b | 2.47 ns | 12.73 *** | 6.59 *** | 1.02 ns | 1.37 ns | 0.81 ns | 0.47 ns |

| Caro | 1.14 ns | 18.21 *** | 12.70 *** | 1.77 ns | 2.40 ns | 1.50 ns | 0.56 ns |

| Pro | 11.22 ** | 15.29 *** | 29.72 *** | 3 ns | 7.80 *** | 2.47 ns | 0.69 ns |

| TSS | 0.55 ns | 1.59 ns | 3.23 * | 0.23 ns | 1.02 ns | 1.10 ns | 0.12 ns |

| TPC | 0.11 ns | 0.50 ns | 0.65 ns | 1.64 ns | 0.00 ns | 0.47 ns | 1.17 ns |

| TF | 2.61 ns | 1.57 ns | 0.84 ns | 0.08 ns | 0.93 ns | 0.96 ns | 2.76 ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martínez-Nieto, M.I.; Penchev Stefanov, E.; Sapiña-Solano, A.; Mircea, D.-M.; Vicente, O.; Boscaiu, M. Environmental Stress Tolerance and Intraspecific Variability in Cortaderia selloana: Implications for Invasion Risk in Mediterranean Wetlands. Agronomy 2026, 16, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010068

Martínez-Nieto MI, Penchev Stefanov E, Sapiña-Solano A, Mircea D-M, Vicente O, Boscaiu M. Environmental Stress Tolerance and Intraspecific Variability in Cortaderia selloana: Implications for Invasion Risk in Mediterranean Wetlands. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Nieto, M. Isabel, Eugeny Penchev Stefanov, Adrián Sapiña-Solano, Diana-Maria Mircea, Oscar Vicente, and Monica Boscaiu. 2026. "Environmental Stress Tolerance and Intraspecific Variability in Cortaderia selloana: Implications for Invasion Risk in Mediterranean Wetlands" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010068

APA StyleMartínez-Nieto, M. I., Penchev Stefanov, E., Sapiña-Solano, A., Mircea, D.-M., Vicente, O., & Boscaiu, M. (2026). Environmental Stress Tolerance and Intraspecific Variability in Cortaderia selloana: Implications for Invasion Risk in Mediterranean Wetlands. Agronomy, 16(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010068