1. Introduction

As one of the three major traded vegetables worldwide, tomatoes are widely cultivated owing to their rich nutritional value [

1]. China is the largest producer of this crop, with the highest output and planting areas worldwide. The tomato industry is of great significance in ensuring the livelihoods of people, increasing farmers’ income and promoting agricultural exports [

2]. Tomato cultivation methods can be classified into open fields and greenhouses. Greenhouse cultivation can effectively reduce the impact of disease and adverse climates and has certain advantages in improving the yield, quality, and economic benefits of tomatoes [

3,

4].

However, in the closed environment of greenhouses, tomatoes, as hermaphroditic crops, rely on effective pollination processes for normal fruit setting. In contrast to open environments, closed greenhouses lack sufficient wind and natural pollination media, such as insects, which often causes flowers to miss the best pollination time, thus affecting the fruit-setting rate and final yield [

5,

6]. Although artificial pollination can be used as a remedial measure, it has inherent defects, such as high labor intensity, low efficiency, and high uncertainty of human operation, which can easily cause uneven pollination, leading to problems such as flower drop, fruit drop, and deformed fruit, reducing the commercial value and economic returns of the fruit [

7]. Therefore, developing a robotic system that can autonomously and accurately identify flowers and perform pollination has become a key technical direction for improving the production efficiency of greenhouse tomatoes and promoting intelligent transformation of agricultural facilities [

8,

9,

10].

In recent years, computer vision technologies, particularly deep learning–based approaches, have achieved significant progress in agricultural object detection tasks and have been increasingly applied to fruit flower recognition and counting. Early studies mainly relied on traditional image processing techniques, such as flower detection based on color space analysis and threshold segmentation. Relevant researchers extracted flower regions using Gaussian filtering combined with color feature analysis, the HSL color space, and RGB channel ratios, respectively [

11,

12,

13]. However, these methods are highly sensitive to illumination variations, background complexity, and flower shape diversity, resulting in limited robustness in complex field environments.

With the rapid development of deep learning, convolutional neural network (CNN)–based detection and segmentation methods have gradually become the mainstream for agricultural flower detection [

14,

15,

16,

17]. For example, Jaju and Chandak [

18] employed ResNet-50 combined with transfer learning to achieve multi-class flower recognition. Lin et al. [

19] integrated an improved VGG19 backbone with Faster R-CNN for strawberry flower detection. Farjon et al. [

20] proposed a Faster R-CNN–based apple flower detection approach to support precision thinning decisions. In addition, Dias et al. [

21] and Sun et al. [

22] utilized DeepLab-based models to achieve fine-grained segmentation of apple, peach, and pear flowers, while Tian et al. [

23] and Mu et al. [

24] further enhanced detection and localization performance in complex inflorescence scenarios by incorporating architectures such as U-Net and Mask R-CNN.

Although these methods have demonstrated promising performance under specific conditions, they generally suffer from large model sizes and slow inference speed, making them unsuitable for real-time, high-precision flower and stamen detection in greenhouse environments. In intelligent agricultural systems—particularly automated pollination applications—flower detection serves as a critical prerequisite for accurate localization and precise operations, where both detection accuracy and processing speed directly affect system performance. Owing to their end-to-end unified architecture, high inference efficiency, and favorable balance between speed and accuracy, the YOLO series has been widely adopted for flower recognition tasks. This has significantly promoted the development of real-time detection solutions in agricultural scenarios. For example, Lyu et al. [

25] proposed a YOLO-HPFD model using a multi-teacher knowledge distillation strategy, achieving an mAP of 94.21% for lychee flower detection in complex backgrounds. Ren et al. [

26] developed the FPG-YOLO model, which improved the detection accuracy of pear flowers by optimizing the network structure and loss function. Bai et al. [

27] introduced an improved YOLOv7-based model for strawberry flower detection, enhancing multiscale feature fusion and global feature perception. Wang et al. [

28] applied YOLOv8 to chili pepper flower detection, achieving high accuracy and recall while maintaining real-time performance. Li et al. [

29] proposed a lightweight YOLOv4-based model for kiwi flower bud detection, obtaining an mAP of 97.61% with high inference efficiency. Xu et al. [

30] improved tomato flower detection by integrating attention mechanisms and multi-angle feature fusion, while Yuying et al. [

31] enhanced YOLOv5s to address illumination and occlusion challenges in apple flower detection, achieving a detection accuracy of 97.2%.

Although YOLO-based target detection methods have made progress in tomato flower recognition, they still face significant challenges in the complex environments of greenhouses. Factors such as foliage shading, overlapping flowers and fruits, variable lighting, and similar morphology among flowers seriously interfere with detection accuracy. Furthermore, existing models generally suffer from complex structures, redundant parameters, and high computational costs, rendering it difficult to meet the application requirements of high accuracy, speed, and real-time performance.

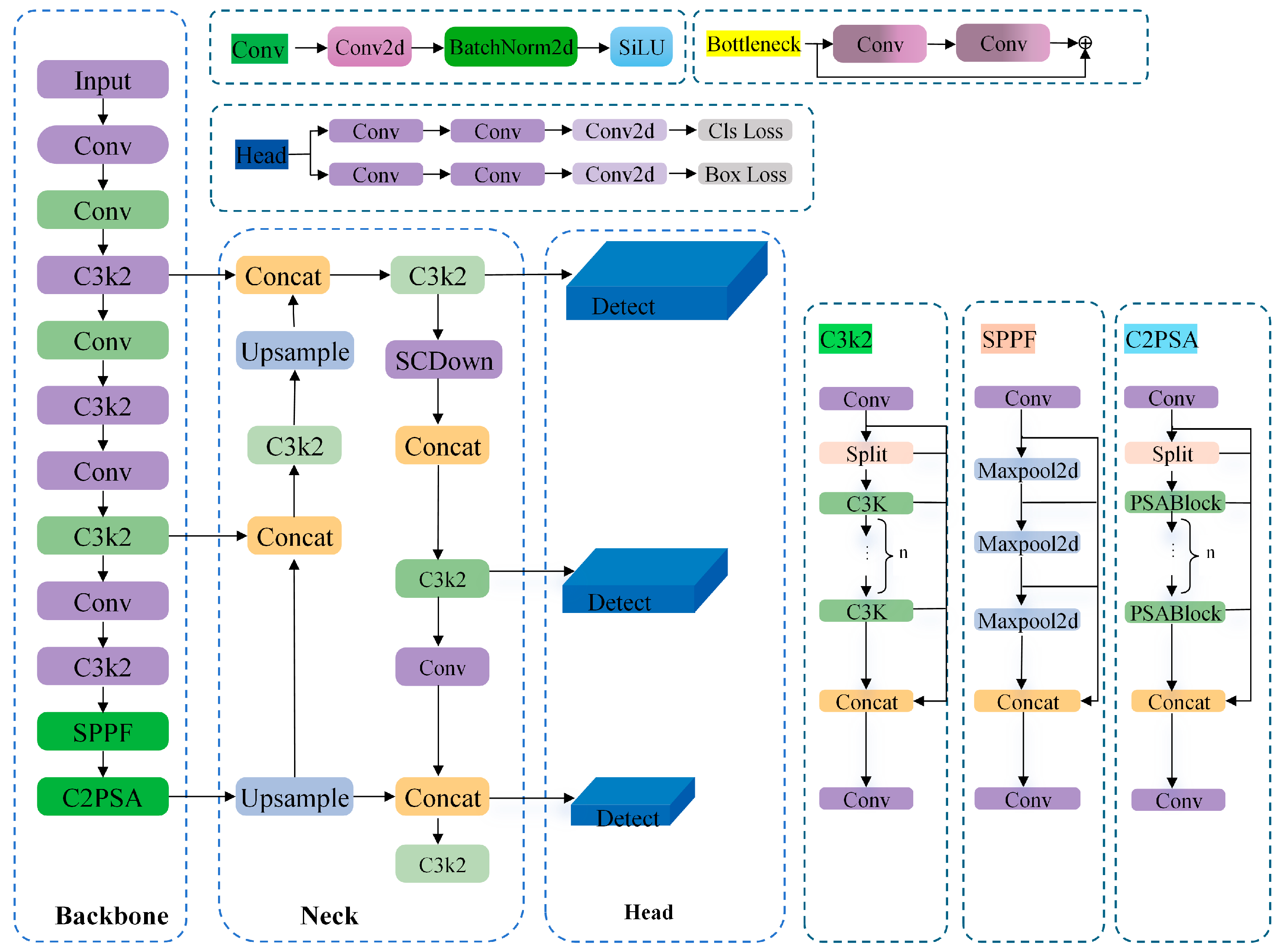

To address the aforementioned challenges, this study proposes a lightweight detection model for greenhouse tomato pollination, termed DSS-YOLO. Taking YOLOv11n as the baseline, the proposed model is developed with the core objective of achieving a favorable balance between lightweight design and accuracy preservation. By collaboratively restructuring backbone feature modeling, downsampling information flow, and bounding box regression optimization, DSS-YOLO realizes a structure-level lightweight detection framework tailored for small-target scenarios. The proposed improvements are summarized as follows:

- (1)

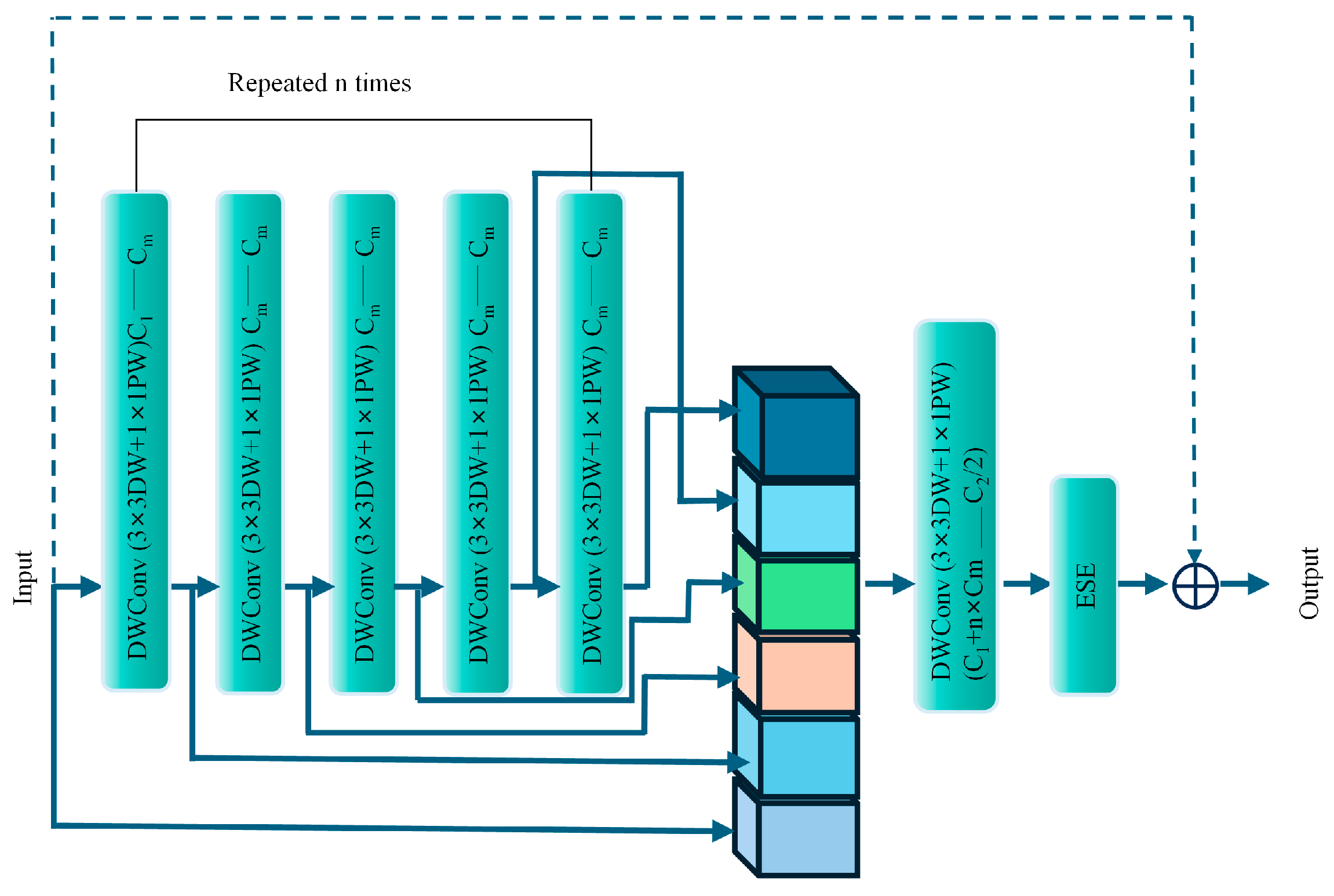

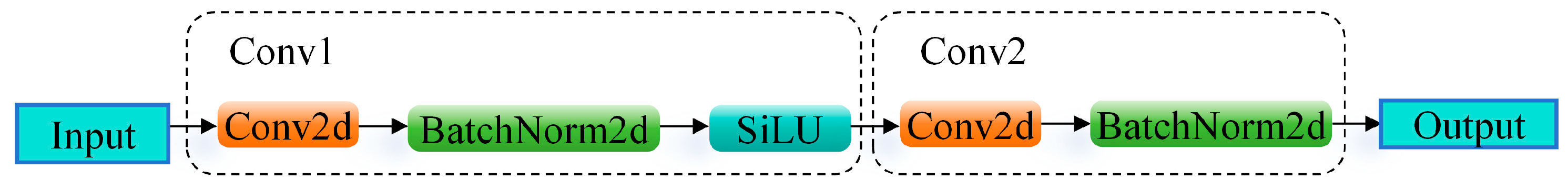

Lightweight backbone network design:

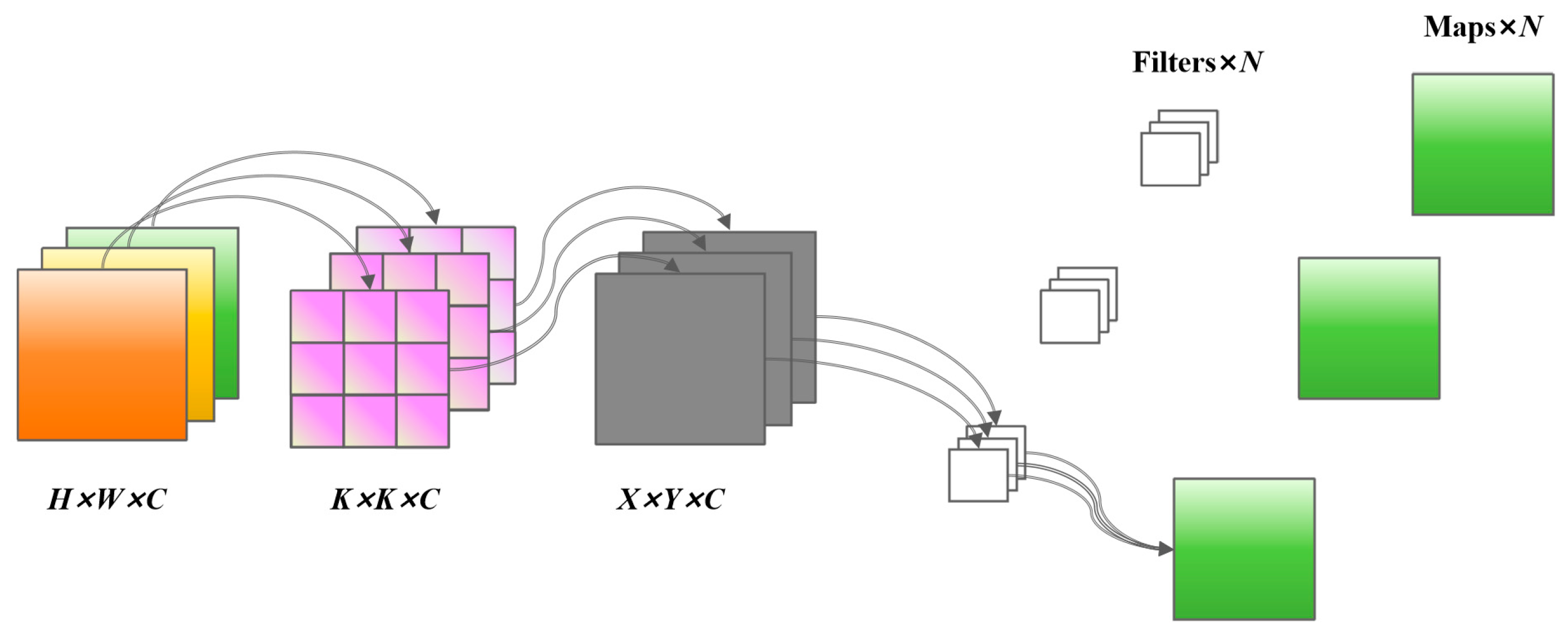

A novel backbone network, DWHGNetv2, is constructed by deeply integrating the efficient architecture of HGNetv2 with depthwise separable convolutions. This design enhances the model’s capability to extract multi-scale and fine-grained features of tomato flowers while significantly reducing the number of parameters and computational complexity, thereby enabling deployment on mobile or embedded devices.

- (2)

Efficient downsampling mechanism optimization:

The SCDown module is introduced to replace conventional standard convolution-based downsampling layers. By decoupling channel transformation and spatial compression, SCDown effectively performs downsampling while preserving critical fine-grained information essential for small-target detection, thereby improving feature fidelity and computational efficiency.

- (3)

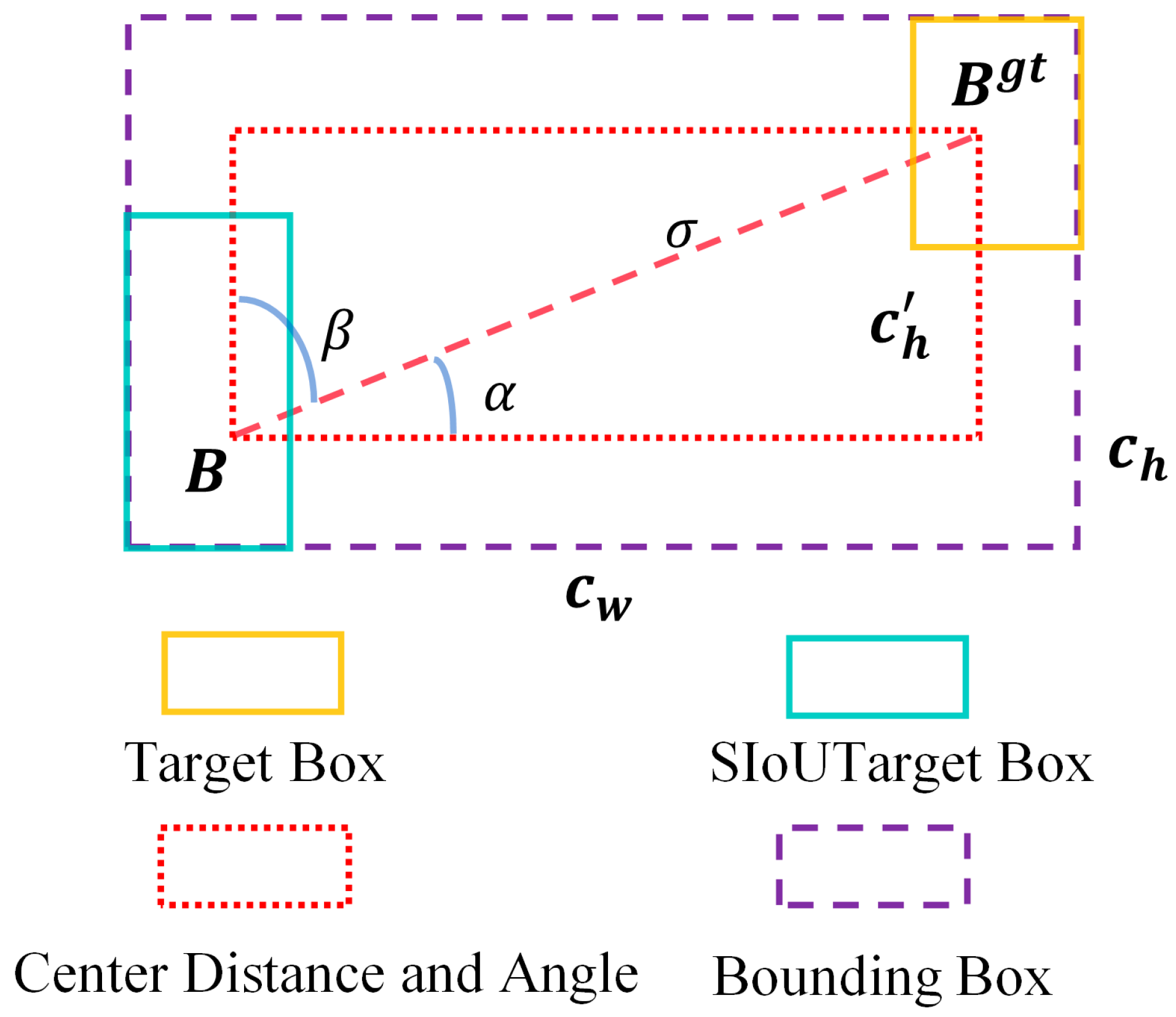

Small-target-oriented loss function improvement:

The SIoU loss function is adopted to optimize bounding box regression. By explicitly incorporating the vector angle relationship between the predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes, SIoU redefines the regression penalty, enabling more accurate localization of direction-sensitive and small-scale targets, such as tomato stamens.

3. Results

3.1. Ablation Experiment

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed improvements for tomato flower pollination detection, YOLOv11n was selected as the baseline model, and a series of ablation experiments were conducted by incrementally incorporating different improvement components into the network. The comparative results of these ablation experiments are summarized in

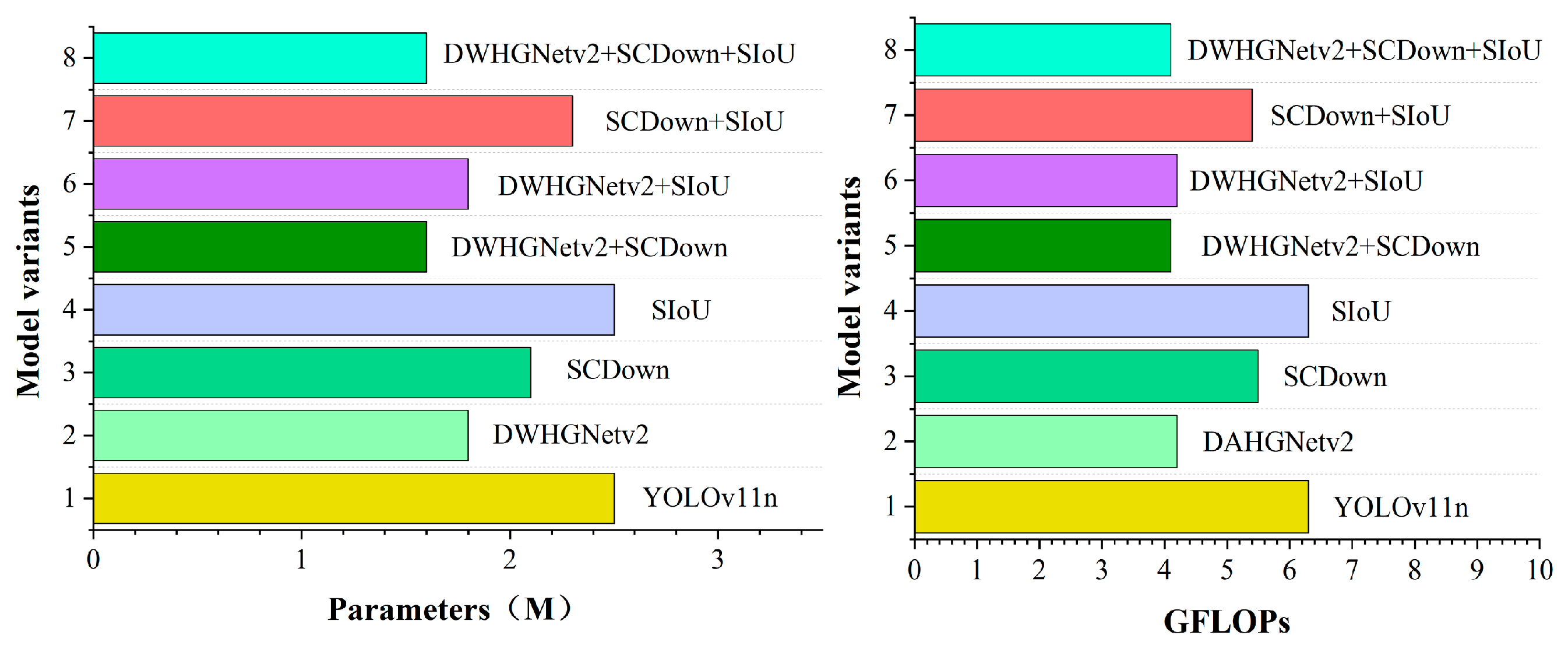

Table 3. In addition,

Figure 8 illustrates the corresponding parameter counts and GFLOPs for each model configuration.

When only DWHGNetv2 (A) is introduced, the number of model parameters is reduced from 2.5 M to 1.8 M, and the FLOPs decrease from 6.3 G to 4.2 G (as illustrated in

Figure 8), indicating a significant reduction in model complexity. However, both Recall and mAP@0.5 show a certain decline, suggesting that replacing the backbone alone is limited in improving detection performance while compressing the model scale. Specifically, DWConv decomposes standard convolution into depthwise and pointwise convolutions, which substantially reduces the number of parameters and computational cost. At the same time, it constrains model capacity at the structural level and reduces redundant inter-channel coupling, thereby alleviating excessive inter-channel redundancy and helping to mitigate overfitting tendencies in scenarios with limited agricultural data, which contributes to improved generalization on the test set. When only SCDown (B) is introduced, the model achieves an improvement in Precision while maintaining a relatively low parameter count, indicating that SCDown can effectively preserve key information during the downsampling process and has a positive impact on detection performance.

When only the SIoU loss function (C) is adopted, both Precision and mAP@0.5 are improved compared with the baseline, with mAP@0.5 reaching 95.3%. This result verifies the advantage of SIoU in terms of bounding box regression accuracy and training stability.

In the combined experiments, A + B significantly reduces the model size while increasing mAP@0.5 to 95.4%, with model weights of only 3.4 MB, demonstrating the strong complementarity between DWHGNetv2 and SCDown. The A + C and B + C combinations further improve detection accuracy, among which B + C shows particularly notable gains in Precision and mAP@0.5.

When all three improvements are simultaneously introduced (A + B + C), the model achieves the best overall performance, with Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5 reaching 94.1%, 94.3%, and 95.9%, respectively. Meanwhile, the model weight and parameter count are reduced to 3.4 MB and 1.6 M, and the FLOPs are only 4.1 G. These results demonstrate that the proposed modules exhibit strong synergistic effects in enhancing detection accuracy while reducing computational complexity. Consequently, the final DSS-YOLO model achieves an optimal balance between performance and lightweight design.

3.2. Comparative Experiment of Mainstream Target Detection Algorithms

To comprehensively evaluate the performance advantages of the proposed DSS-YOLO model, comparative experiments were conducted under a unified hardware platform and software environment. Several mainstream lightweight object detection algorithms were evaluated, while larger variants were included for reference only. The compared methods include Faster R-CNN [

19,

20], ShuffleNetV2 [

43], MobileNetV4 [

36], YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9-tiny, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n as well as the proposed DSS-YOLO model. Inference speed (FPS) was measured on the GPU to ensure fairness and consistency in speed evaluation across different models. The experimental results are presented in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 4, the traditional two-stage detector Faster R-CNN achieves relatively high detection accuracy; however, it suffers from an excessively large model size (521.5 MB), as well as extremely high parameter count and computational complexity. This large model size is mainly attributed to its high number of parameters stored in full-precision format, which leads to substantially increased memory consumption. Consequently, its inference speed is limited to only 10 FPS, making it unsuitable for real-time tomato flower detection in greenhouse environments.

Compared with Faster R-CNN, lightweight backbone-based models such as ShuffleNetV2 and MobileNetV4 significantly reduce model size, parameters, and FLOPs. However, this reduction in complexity comes at the cost of limited detection performance, particularly in terms of precision and recall, which restricts their applicability in complex greenhouse scenes with occlusion and small targets. YOLOv3-tiny offers moderate inference speed, but its mAP@0.5 is noticeably lower than that of more recent YOLO-based detectors, resulting in inferior overall performance.

Among the one-stage YOLO-series models, YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9-tiny, and YOLOv10n demonstrate a more favorable balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. These models achieve mAP@0.5 values above 94.6% while maintaining real-time inference speeds ranging from 31 to 53 FPS. Nevertheless, their parameter counts and computational costs remain higher than those of ultra-lightweight architectures, and further improvements in accuracy are often accompanied by increased complexity.

In contrast, the proposed DSS-YOLO achieves the best overall performance among all compared models. It attains the highest mAP@0.5 of 95.9%, along with superior precision (94.1%) and recall (94.3%). At the same time, DSS-YOLO maintains an extremely compact model size of only 3.4 MB, with 1.6 M parameters and 4.1 GFLOPs, which is comparable to or lower than most lightweight networks. Moreover, DSS-YOLO achieves the fastest inference speed of 65 FPS, outperforming all other mainstream algorithms evaluated in this study.

Overall, these results demonstrate that DSS-YOLO provides a more favorable trade-off among detection accuracy, model lightweightness, and inference speed. This balanced performance makes DSS-YOLO particularly suitable for real-time tomato flower detection and intelligent pollination applications in resource-constrained greenhouse environments, highlighting its strong potential for practical deployment.

3.3. Comparison Experiments of Different Downsampling Layers

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed SCDown module in multi-scale feature extraction and information preservation, a series of systematic comparative experiments were conducted in this section. During the downsampling stage, three representative methods were introduced for comparison: ADown (adaptive downsampling), SAConv (switchable atrous convolution–based downsampling), and SPDConv (sparse pyramid dynamic convolution–based downsampling). These approaches aim to reduce computational complexity while preserving critical semantic information through mechanisms such as dynamic receptive field adjustment, feature redundancy suppression, and sparse computation. Through comparative experiments, the comprehensive impact of different downsampling layers on model accuracy, parameter count, GFLOPs, and model size was analyzed. The experimental comparison results are presented in

Table 5.

Table 5 compares the effects of different downsampling modules on detection performance and computational complexity under the same network architecture and training strategy. In terms of detection accuracy, SCDown achieves the best overall performance across all three metrics—Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5—with the mAP@0.5 reaching 95.1%, representing improvements of 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.6% over ADown, SAConv, and SPDConv, respectively. These results indicate that SCDown can more effectively preserve critical feature information during the downsampling process, thereby enhancing the detection accuracy of tomato flower targets.

Regarding model complexity, SCDown maintains high detection performance while incurring relatively low computational overhead. The model equipped with SCDown has a weight size of 4.1 MB, 2.0 M parameters, and 5.5 G, which are comparable to those of ADown and significantly lower than those of SAConv and SPDConv. Although SAConv and SPDConv enhance feature representation to some extent, they introduce additional parameters and computational cost. In particular, SPDConv exhibits a substantially higher computational burden, with FLOPs reaching 11.4 G, which limits its suitability for real-time detection applications.

Overall, SCDown achieves a more favorable trade-off between detection accuracy and computational efficiency, improving the model’s ability to represent key tomato flower features while avoiding excessive computational overhead. Therefore, SCDown is selected as the downsampling module in DSS-YOLO, providing effective support for the overall performance enhancement of the proposed model.

3.4. Comparison Experiments of Different Loss Functions

Within the YOLO framework, the design of the loss function has a direct impact on model optimization efficiency and detection performance. To address the challenges encountered in greenhouse tomato flower and stamen detection—such as large variations in target scale, strong background interference, and difficulty in recognizing small objects—this study introduces the SIoU loss function and conducts a systematic comparison with several mainstream bounding box regression losses, including GIoU, EIoU, and WIoU. The objective is to investigate the influence of different loss functions on the model convergence behavior and final detection accuracy. The comparative experimental results are presented in

Table 6.

Table 6 presents the impact of different bounding box regression loss functions on the detection performance of the model under identical experimental settings. Clear differences can be observed among the loss functions in terms of Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5, indicating that the choice of bounding box regression strategy plays a crucial role in tomato flower detection.

Overall, SIoU achieves the best performance across all three evaluation metrics, with Precision and Recall reaching 93.5% and 93.3%, respectively, and mAP@0.5 attaining 95.3%. Compared with GIoU, EIoU, and WIoU, SIoU demonstrates a clear advantage, suggesting that jointly modeling angular alignment, center distance, and overlap during regression effectively improves the matching accuracy between predicted boxes and ground-truth targets.

In contrast, GIoU exhibits relatively stable Precision and Recall but yields a lower mAP@0.5, implying limited localization accuracy in complex scenarios. Although EIoU achieves a certain improvement in mAP@0.5, its Precision and Recall decrease slightly, which may lead to increased false positives or missed detections. WIoU shows the weakest overall performance, with all three metrics falling below those of the other loss functions, indicating limited adaptability to the present dataset.

Based on the above analysis, SIoU provides the best balance between detection accuracy and stability and is therefore more suitable for tomato flower detection in complex greenhouse environments. Accordingly, SIoU is selected as the bounding box regression loss function for DSS-YOLO to further enhance detection performance.

3.5. Visual Analysis of Results

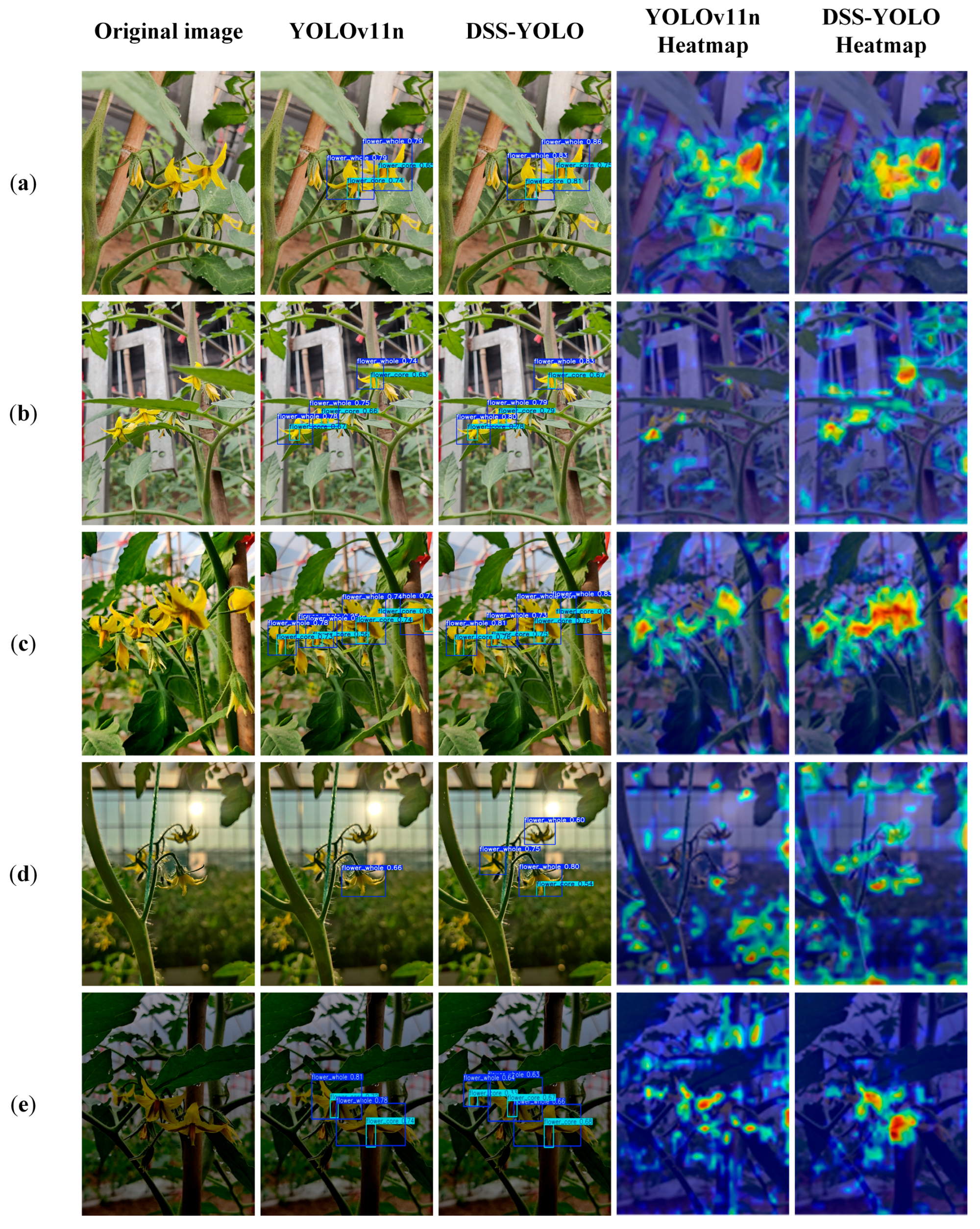

To provide a more intuitive evaluation of the detection performance of the improved DSS-YOLO model, a comparative analysis between YOLOv11n and DSS-YOLO was conducted on the tomato flower test set under complex greenhouse conditions. The comparison considered two factors: different shooting distances and varying illumination conditions. In addition, the Grad-CAM method was employed to visualize the feature response regions of the models. Grad-CAM generates heatmaps to highlight the image regions that receive the highest attention during inference, thereby offering further insight into the capability of DSS-YOLO to detect tomato flower targets under diverse environmental conditions. The corresponding detection and visualization results are presented in

Figure 9.

In close-range scenarios, both models are able to accurately detect tomato flowers. However, DSS-YOLO demonstrates superior localization stability and confidence for both the flower body and the floral center, with feature responses more consistently concentrated on key flower structures and less influenced by background interference. In contrast, the feature activation of YOLOv11n appears more dispersed. In long-distance scenarios, YOLOv11n is prone to missed detections and localization deviations, whereas DSS-YOLO maintains effective attention to small-scale flower targets. The Grad-CAM heatmaps further indicate that DSS-YOLO exhibits more prominent feature activation for distant small targets, highlighting its advantage in small-object detection under complex conditions.

Under varying illumination conditions, both models retain a certain level of detection capability; however, DSS-YOLO shows greater stability and robustness. Under front-lighting conditions, DSS-YOLO focuses more effectively on critical regions such as the floral center in scenes involving flower overlap and leaf occlusion, while YOLOv11n still exhibits relatively strong responses to non-target regions. Under backlighting and low-light conditions, YOLOv11n suffers from noticeably reduced detection stability due to blurred contours, decreased contrast, and noise interference, often resulting in reduced confidence scores or missed detections. By comparison, DSS-YOLO continues to concentrate on flower structural regions with more compact feature responses, demonstrating stronger robustness and reliability in challenging illumination environments. Although DSS-YOLO maintains relatively stable feature activation on flower structures, several typical failure cases can still be observed in

Figure 9, including false detections under low-light conditions and increased attention to non-target objects in the corresponding heatmaps. These failures mainly occur when object boundaries are severely degraded or when the foreground–background contrast is extremely low.

The comparative analysis of feature heatmaps shows that DSS-YOLO consistently produces more concentrated activation regions across different scenarios, primarily focusing on tomato flowers and their floral centers, whereas YOLOv11n exhibits more scattered responses and is more susceptible to background interference. This observation indicates that DSS-YOLO possesses stronger discriminative capability in feature extraction and target representation, which contributes to reducing both false positives and missed detections.

Overall, the visualization results demonstrate that DSS-YOLO consistently outperforms the baseline YOLOv11n model under different shooting distances and complex illumination conditions. Its improved performance in small-target detection, background suppression, and attention to key structural regions provides a more reliable visual perception foundation for automated tomato flower recognition and intelligent pollination in greenhouse environments.

4. Discussion

The DSS-YOLO model proposed in this study demonstrates strong overall performance in detecting greenhouse tomato flowers and stamens. The key methodological contribution lies in a systematic strategy that jointly optimizes model lightweightness and detection accuracy. Compared with traditional image processing approaches based on handcrafted features, the end-to-end DSS-YOLO framework can automatically learn more discriminative and robust high-level features directly from data. Conventional methods typically rely on serial pipelines composed of preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, and classification modules, which require extensive parameter tuning and often suffer from limited generalization under complex greenhouse conditions, such as variable illumination, foliage occlusion, and dense flower clustering. In contrast, DSS-YOLO effectively overcomes these limitations, exhibiting superior adaptability and robustness in complex scenarios.

The results of this study are consistent with recent trends in lightweight agricultural object detection while achieving targeted improvements for greenhouse pollination applications. For example, Lyu et al. [

25] demonstrated that lightweight network designs help maintain sensitivity to densely occluded litchi flowers under limited computational resources, while Bai et al. [

27] showed that efficient feature-fusion mechanisms improve strawberry flower detection in complex backgrounds. Building upon these findings, this study specifically targets the agricultural task of automated pollination. By accurately defining open flowers and clearly visible stamens suitable for pollination as detection targets, and by systematically integrating a lightweight backbone, efficient downsampling, and a direction-aware loss function, DSS-YOLO achieves higher detection accuracy and robustness under varying illumination and viewing angles. These results provide a more reliable visual perception solution for the practical deployment of automated pollination systems in greenhouse environments.

Despite the excellent performance of DSS-YOLO, a scope for improvement exists in its generalizability and performance. The test set in this study strictly followed the same acquisition criteria as the training set and included images captured at different times of the day (09:00, 14:00, and 18:00), thereby providing a preliminary validation of the model’s robustness to daily illumination variations. However, several limitations of the dataset remain. First, all data were collected from a single greenhouse and a single tomato cultivar (Provence tomato) within one geographic region. As a result, the generalization capability of the proposed model to different regions, tomato varieties (e.g., cherry tomatoes and beefsteak tomatoes), and greenhouse structures, as well as its robustness to extreme environmental disturbances (such as lens fogging caused by high humidity), were not investigated in this study. These aspects will be systematically evaluated in future work using more diverse and extensive datasets. Second, although the SIoU loss function improves overall localization accuracy, its regression capability for extremely elongated or heavily occluded stamens may be approaching a performance bottleneck. Future studies may therefore explore more specialized shape modeling and constraint strategies to further enhance robustness under such challenging conditions. Finally, although the proposed model has been lightweight, deployment on ultra–low-power embedded devices will likely require the integration of advanced model compression techniques, such as network pruning, quantization, or knowledge distillation, to further exploit its efficiency potential [

44,

45,

46].

In summary, DSS-YOLO provides an efficient and practical solution for identifying the tomato pollination status in greenhouse environments. Future work will focus on building a cross-regional multivariate dataset, exploring specialized regression loss functions for slender objects, and promoting the deployment of the model on edge computing platforms, achieving full implementation of smart agriculture technologies.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the demand for high-precision and lightweight visual models in greenhouse tomato pollination by proposing a novel detection framework, termed DSS-YOLO. Built upon YOLOv11n, the proposed model systematically enhances feature extraction, information preservation, and bounding box regression through three key improvements: the construction of a lightweight backbone network, DWHGNetv2, based on depthwise separable convolutions; the introduction of an SCDown downsampling module to decouple channel transformation and spatial compression for better preservation of small-target information; and the adoption of an SIoU loss function with an angle-aware mechanism to improve localization accuracy.

Experimental results demonstrate that DSS-YOLO achieves an excellent balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. Compared with the baseline YOLOv11n, the model size, parameter count, and computational cost are reduced by 34%, 36%, and 35%, respectively, while precision, recall, and mAP@0.5 are improved by 1.1%, 1.0%, and 0.7%, respectively. Meanwhile, DSS-YOLO maintains a real-time inference speed of 65 FPS, outperforming mainstream lightweight detection models.

Overall, this research provides a reliable visual perception solution for automated greenhouse pollination and offers a valuable technical reference for other resource-constrained agricultural vision applications.