From Salt Tolerance Threshold Analysis to Optimized Cultivation: An Integrated Variety–Technology Pathway for the Forage Mulberry Variety ‘Fengyuan No. 1’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Sites

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Pot-Based Salt Stress Experiment

2.2.2. Field Cultivation Experiment

2.3. Measurements and Methods

2.3.1. Growth and Morphological Parameters

2.3.2. Physiological and Biochemical Components

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Salt Tolerance Threshold and Physiological Growth Responses of ‘Fengyuan No. 1’

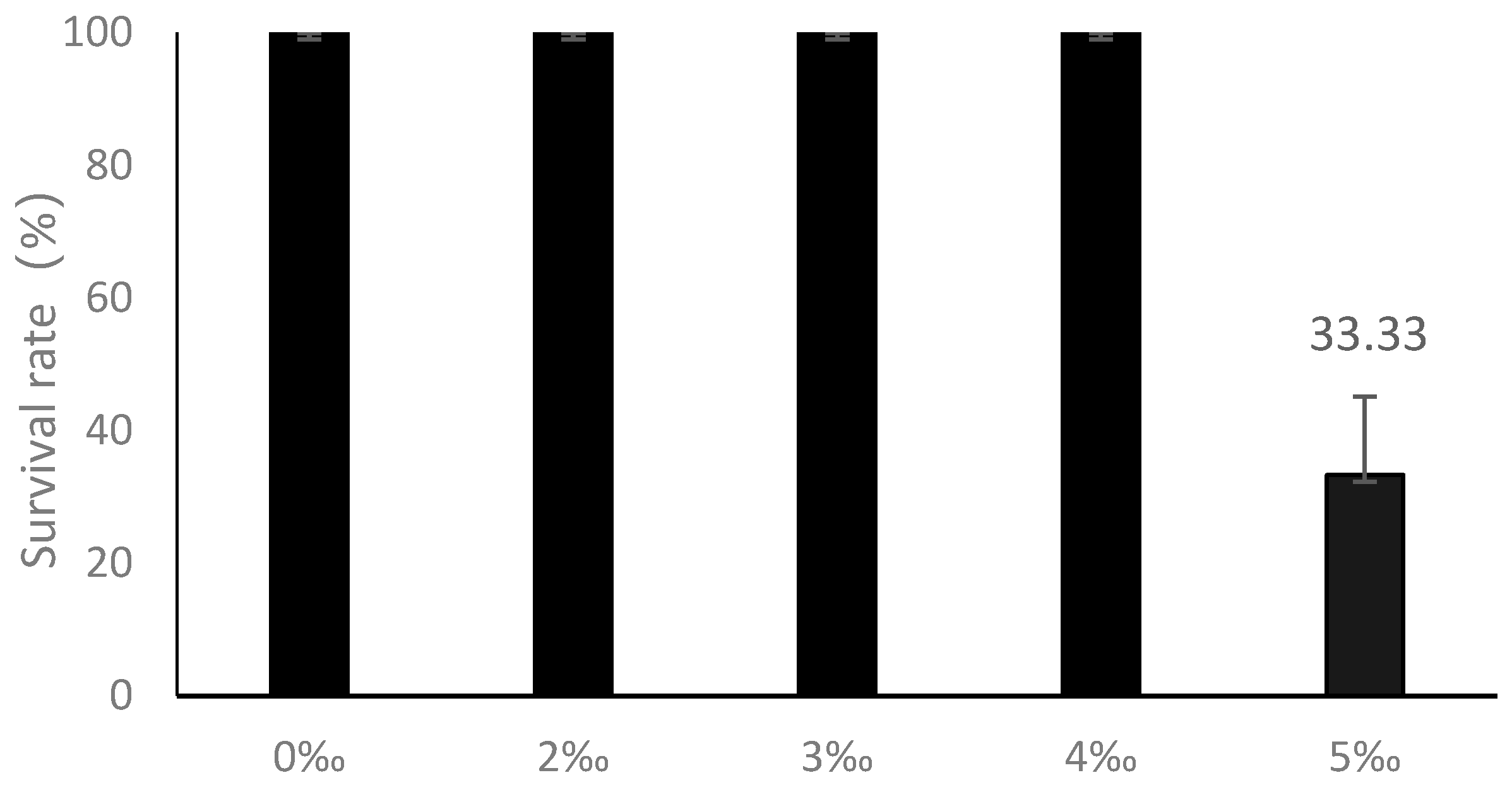

3.1.1. Survival Rate and Salt Injury Symptoms Define Tolerance Limits

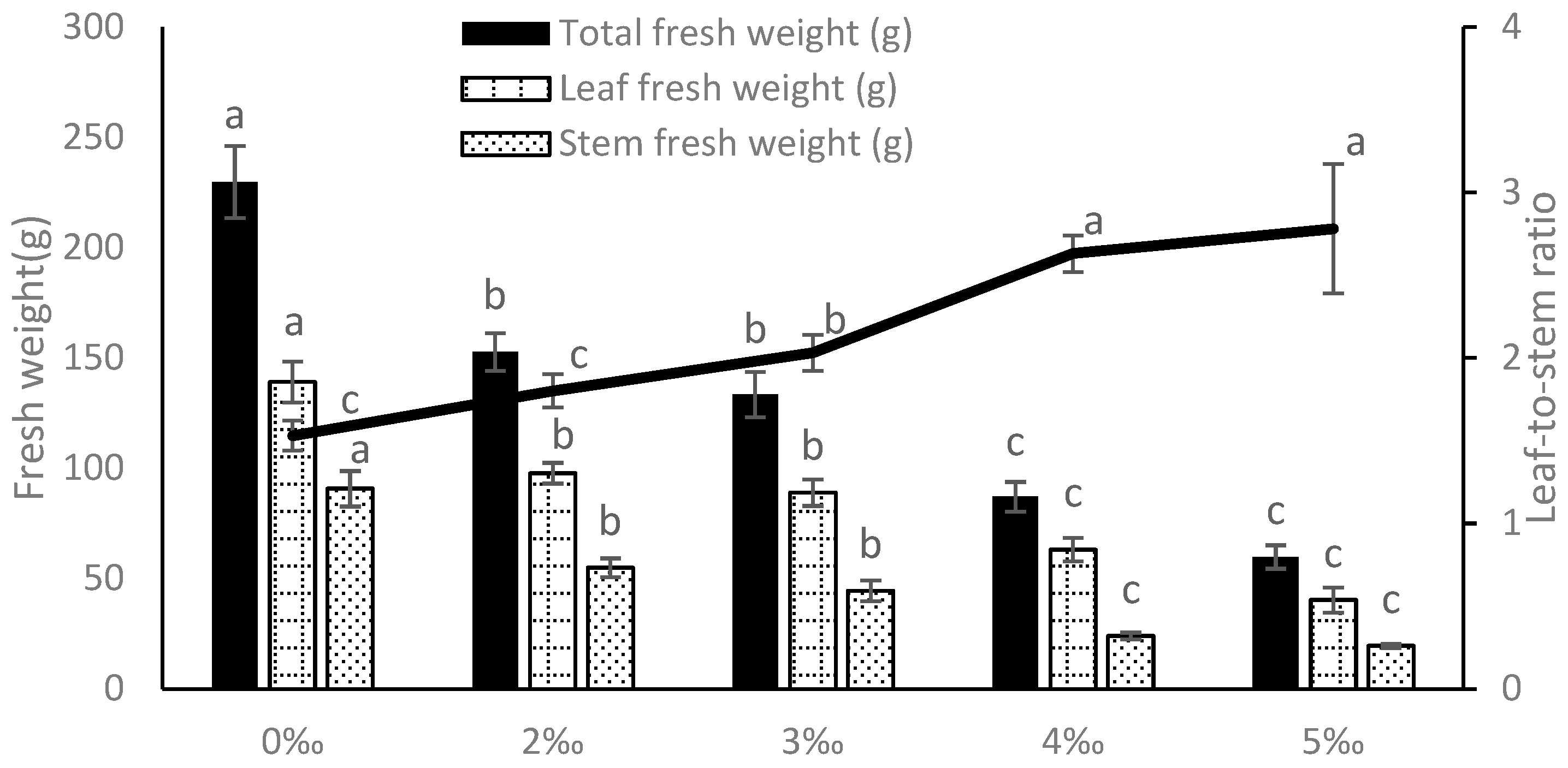

3.1.2. Biomass Allocation Strategy Reveals Resource Optimization Pathway

3.1.3. Leaf Morphological Adaptation Demonstrates Structural Stress Resilience

3.2. Impact of Optimized Cultivation Pathways on Plant Growth

3.3. Regulation of Leaf Components by Optimized Cultivation Pathways

4. Discussion

4.1. Salt Tolerance and Physiological Response Mechanism of ‘Fengyuan No. 1’—The Starting Point of the Integrated Pathway

4.2. Effects of Cultivation Mode on Growth and Composition—Diversified Options Within the Integrated Pathway

4.3. Functional Component Response and Metabolic Regulation—The Quality Dimension of Pathway Selection

4.4. Application Prospects and Sustainability Outlook—Towards a Complete Industrial Pathway

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Salt-Affected Soils and Their Management; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, N.; Sun, G. Use of mulberry-soybean intercropping in salt-alkali soil impacts the diversity of the soil bacterial community. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, A.K.; Das, A.B. Salt tolerance and salinity effects on plants: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2005, 60, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, K.; Doss, S.G.; Chakraborti, S.P.; Ghosh, P.D. Breeding for salinity resistance in mulberry (Morus spp.). Euphytica 2009, 169, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.U.; Arshad, M.A.; Li, M.; Rehman, M.S.; Loor, J.J.; Huang, J. Potential of Mulberry Leaf Biomass and Its Flavonoids to Improve Production and Health in Ruminants: Mechanistic Insights and Prospects. Animals 2020, 10, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, B.; Gao, J.; Cheng, H.; Guo, G.; Wang, Z. Effects of dietary mulberry leaves on growth, production performance, gut microbiota, and immunological parameters in poultry and livestock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Yin, Z.; Zhu, W.; Li, J.; Meng, L.; Zhong, H.; Xu, N.; Wu, Y.; et al. Rootstock Alleviates Salt Stress in Grafted Mulberry Seedlings: Physiological and PSII Function Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Wu, L. Breeding for salinity tolerance in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1994, 13, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.G.; Lakshmi, A.; Madhusudhan, K.; Ramanjulu, S.; Sudhakar, C. Photosynthesis Parameters in Two Cultivars of Mulberry Differing in Salt Tolerance. Photosynthetica 2000, 36, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.G.; Reddy, A.M.; Sudhakar, C. NaCl effects on proline metabolism in two high yielding genotypes of mulberry (Morus alba L.) with contrasting salt tolerance. Plant Sci. 2003, 165, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Luo, Z.; Ke, Y.; Dai, L.; Duan, H.; Hou, R.; Cui, B.; Dou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Growth, Physiological, Biochemical, and Ionic Responses of Morus alba L. Seedlings to Various Salinity Levels. Forests 2017, 8, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Ali, Q. Relative membrane permeability and activities of some antioxidant enzymes as the key determinants of salt tolerance in canola (Brassica napus L.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Gao, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Li, J. Evaluation of salinity resistance and combining ability analysis in the seedlings of mulberry hybrids (Morus alba L.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2023, 29, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, K.; Chakraborti, S.P.; Doss, S.G.; Ghosh, P.D.; Ercisli, S. Combining ability for morphological and biochemical characters in mulberry (Morus spp.) under salinity stress. Int. J. Ind. Entomol. 2008, 16, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sudharani, M.; Reddy, P.R.; Badu, V.R.; Reddy, G.H.; Raju, C.S. Combining ability studies in rice (Oryza sativa L.) under coastal saline soil conditions. Madras Agric. J. 2013, 100, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Guo, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Geng, B. Response of Yield and Protein Content of Forage Mulberry to Irrigation in North China Plain. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y/T 2890-2016; Determination of γ-aminobutyric acid in rice-High performance liquid chromatography. Ministry of Agriculture of the People‘s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Shi, X.Q.; Cui, W.Z.; Xi, L.Q.; Duan, Z.A.; Wu, X.F. Determination of 1-deoxynojirimycin by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. Sci. Seric. 2006, 1, 146–149. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.5-2016; National food safety standard-Determination of protein in foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.268-2016; National food safety standard-Determination of multi-elements in foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Liu, X.Q.; Ding, T.L.; Wei, C.J.; Long, D.; Guo, Q.; Zhu, F.; He, N.; Yu, M.; Xiang, Z. An evaluation on salt and drought tolerance of F1 generations from 13 mulberry hybrid combinations. Acta Sericologica Sin. 2014, 40, 764–773. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, A.; Sengupta, D.; Reddy, A.R. Physiological optimality, allocation trade-offs and antioxidant protection linked to better leaf yield performance in drought exposed mulberry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 2649–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.; Li, S.; Cui, X. Leaf morphology and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of mulberry seedlings under waterlogging stress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yin, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, Y. Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Composition of Mulberry (Morus spp.) under Drought Stress. Forests 2023, 14, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, P.; Jaleel, C.A.; Sharma, S. Antioxidant defense system, lipid peroxidation, proline-metabolizing enzymes, and biochemical activities in two Morus alba genotypes subjected to NaCl stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 57, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Lu, J.; Xiang, Y.; Shi, H.; Sun, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F. Farmland mulching and optimized irrigation increase water productivity and seed yield by regulating functional parameters of soybean (Glycine max L.) leaves. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 298, 108875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Plant Salt Tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2001, 6, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.; Hafeez, M.B.; Kausar, A.; Al Zeidi, M.; Asekova, S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Plant photosynthetic responses under drought stress: Effects and management. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2023, 209, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Dar, M.A.; Dhanavade, M.J.; Abbas, S.Z.; Bukhari, M.N.; Arsalan, A.; Liao, Y.; Wan, J.; Shah Syed Bukhari, J.; Ouyang, Z. Biosynthesis and Pharmacological Activities of the Bioactive Compounds of White Mulberry (Morus alba): Current Paradigms and Future Challenges. Biology 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, T.; Turkan, I. Comparative lipid peroxidation, antioxidant defense systems and proline content in roots of two rice cultivars differing in salt tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2005, 53, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelp, B.J.; Bown, A.W.; McLean, M.D. Metabolism and functions of gamma-aminobutyric acid. Trends Plant Sci. 1999, 4, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.A.; Tyerman, S.D.; Gilliham, M.; Xu, B. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) signalling in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 1577–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackah, M.; Shi, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.; Guo, P.; Guo, L.; Jin, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, C.; et al. Metabolomics Response to Drought Stress in Morus alba L. Variety Yu-711. Plants 2021, 10, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Peng, Y.; He, J.; Chen, C.; Xiao, D.; Yin, Y.; Li, F. Mulberry leaf powder regulates antioxidative capacity and lipid metabolism in finishing pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappa, L.; Dari, J.; Modanesi, S.; Quast, R.; Brocca, L.; De Lannoy, G.; Massari, C.; Quintana-Seguí, P.; Barella-Ortiz, A.; Dorig, W. Benefits and pitfalls of irrigation timing and water amounts derived from satellite soil moisture. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 295, 108773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivation Mode | Specification Description |

|---|---|

| Ridge Planting (RP) | Ridge height, 30 cm; ridge top width, 50 cm; ridge spacing, 80 cm |

| Furrow Planting (FP) | Ridge height, 30 cm; furrow bottom width, 30 cm |

| Flat-Bed Planting (FBP) | Bed width, 1.0 m; no ridges/furrows on beds; 20 cm walkways between beds |

| Analyte | Method/Standard | Primary Instrument and Model |

|---|---|---|

| γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) | NY/T 2890-2016 [18] | High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph, Agilent 1260 (Agilent, Beijing, China) |

| 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) | Pre-column derivatization-HPLC method, ref. [19] | High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph, Agilent 1260 |

| Crude Protein | GB 5009.5-2016 Kjeldahl method [20] | Automatic Kjeldahl Nitrogen Analyzer, K9840 (Jinan Haineng Instrument Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) |

| Mineral Elements (Na+, K+, etc.) | GB 5009.268-2016 ICP-MS [21] | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer, ICP-MS iCAP RQ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) |

| Parameter | Ridge Planting (RP) | Furrow Planting (FP) | Flat-Bed Planting (FBP) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Height (cm) | 75.83 ± 11.76 a | 113.18 ± 8.29 b | 100.83 ± 11.64 ab | 0.028 |

| Base Diameter (mm) | 13.07 ± 1.45 a | 19.74 ± 2.07 b | 19.85 ± 4.32 b | 0.008 |

| Root FW (g) | 35.17 ± 12.86 a | 93.08 ± 21.05 ab | 176.45 ± 75.12 b | 0.001 |

| Stem FW (g) | 92.53 ± 26.76 a | 147.83 ± 32.77 ab | 216.05 ± 90.63 b | 0.021 |

| Leaf FW (g) | 146.67 ± 36.54 a | 196.78 ± 35.33 ab | 225.83 ± 18.62 b | 0.032 |

| Component | Ridge Planting (RP) | Furrow Planting (FP) | Flat-Bed Planting (FBP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Protein (g/100 g) | 23.3 ± 2.55 a | 24.7 ± 3.69 a | 21.2 ± 2.10 b |

| NDF (g/100 g) | 28.03 ± 3.90 b | 40.56 ± 5.72 a | 27.6 ± 2.62 b |

| ADF (g/100 g) | 13.80 ± 1.84 c | 25.60 ± 3.73 a | 22.80 ± 3.06 b |

| GABA (mg/kg) | 589.96 ± 68.31 a | 583.51 ± 64.06 a | 217.76 ± 38.53 b |

| DNJ (mg/kg) | 133.69 ± 17.93 b | 137.63 ± 12.25 b | 215.16 ± 29.73 a |

| Na+ (mg/kg) | 200.02 ± 27.53 a | 150.43 ± 26.87 b | 124.90 ± 15.83 c |

| K+ (mg/kg) | 24,300 ± 3581 a | 18,500 ± 1932 b | 25,000 ± 2846 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Geng, B.; Ren, Y.; Dong, Y.; Guo, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, D. From Salt Tolerance Threshold Analysis to Optimized Cultivation: An Integrated Variety–Technology Pathway for the Forage Mulberry Variety ‘Fengyuan No. 1’. Agronomy 2026, 16, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010003

Geng B, Ren Y, Dong Y, Guo G, Wang Z, Zhao D. From Salt Tolerance Threshold Analysis to Optimized Cultivation: An Integrated Variety–Technology Pathway for the Forage Mulberry Variety ‘Fengyuan No. 1’. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Bing, Yujie Ren, Yaru Dong, Guang Guo, Zhaohong Wang, and Dongxiao Zhao. 2026. "From Salt Tolerance Threshold Analysis to Optimized Cultivation: An Integrated Variety–Technology Pathway for the Forage Mulberry Variety ‘Fengyuan No. 1’" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010003

APA StyleGeng, B., Ren, Y., Dong, Y., Guo, G., Wang, Z., & Zhao, D. (2026). From Salt Tolerance Threshold Analysis to Optimized Cultivation: An Integrated Variety–Technology Pathway for the Forage Mulberry Variety ‘Fengyuan No. 1’. Agronomy, 16(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010003