Water and Nitrogen Regulation of Tea Leaf Volatiles Influences Ectropis grisescens Olfaction

Abstract

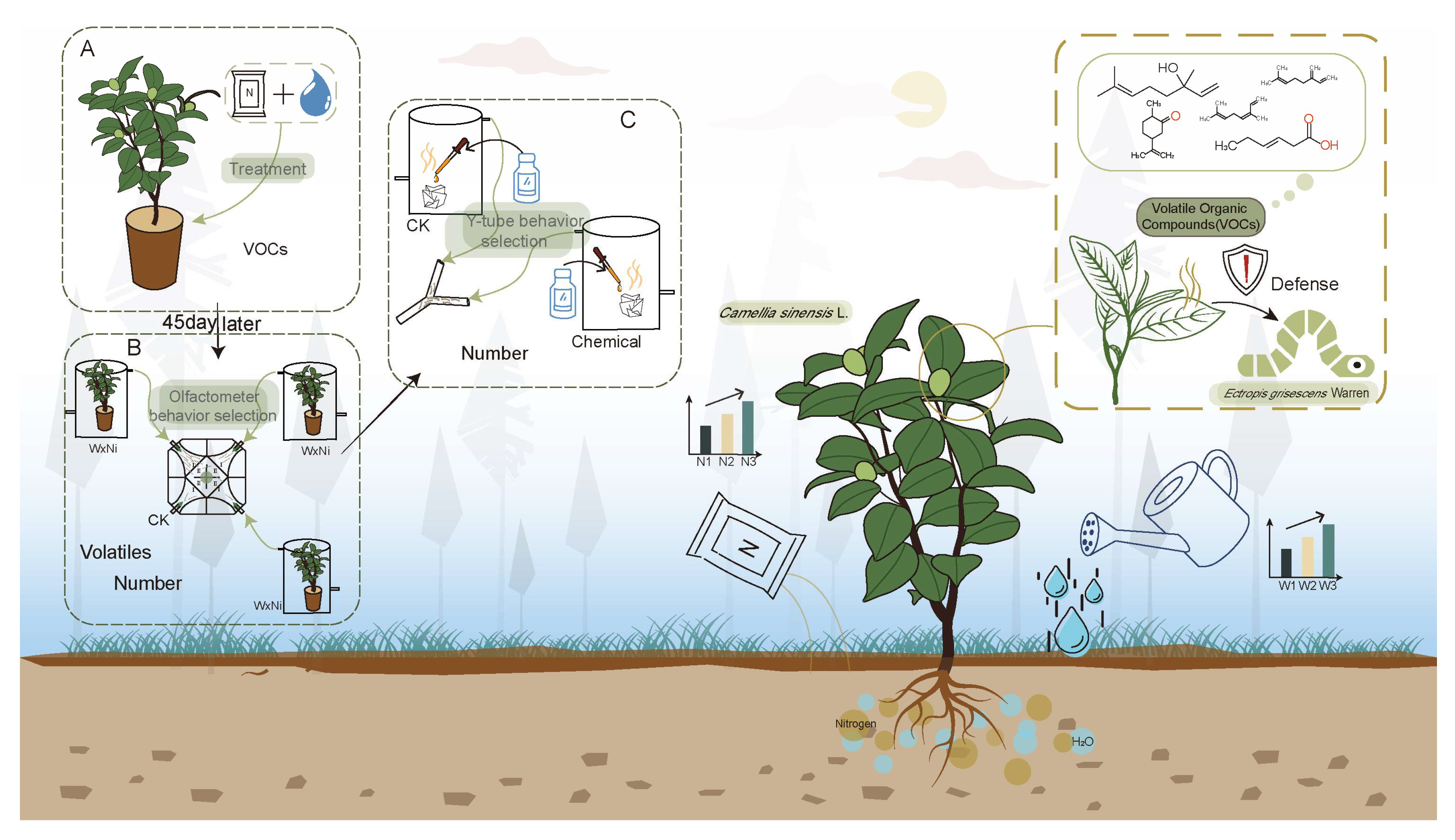

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Experimental Setup of Soil Moisture and Nitrogen Treatments

2.3. Behavioral Choice Test of Ectropis grisescens with Fresh Tea Leaves Under Different Water and Nitrogen Treatments Using a Four-Arm Olfactometer

2.4. Behavioral Choice Test of Ectropis grisescens with Different VOCs Using a Y-Tube Olfactometer

2.5. Collection of Fresh Tea Leaves

2.6. Identification of Volatile Organic Compounds in Fresh Tea Leaves

2.7. Calculation of Relative Content of Standard Chemicals

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Different Water and Nitrogen Treatments on the Preference of Ectropis grisescens for Fresh Tea Leaves

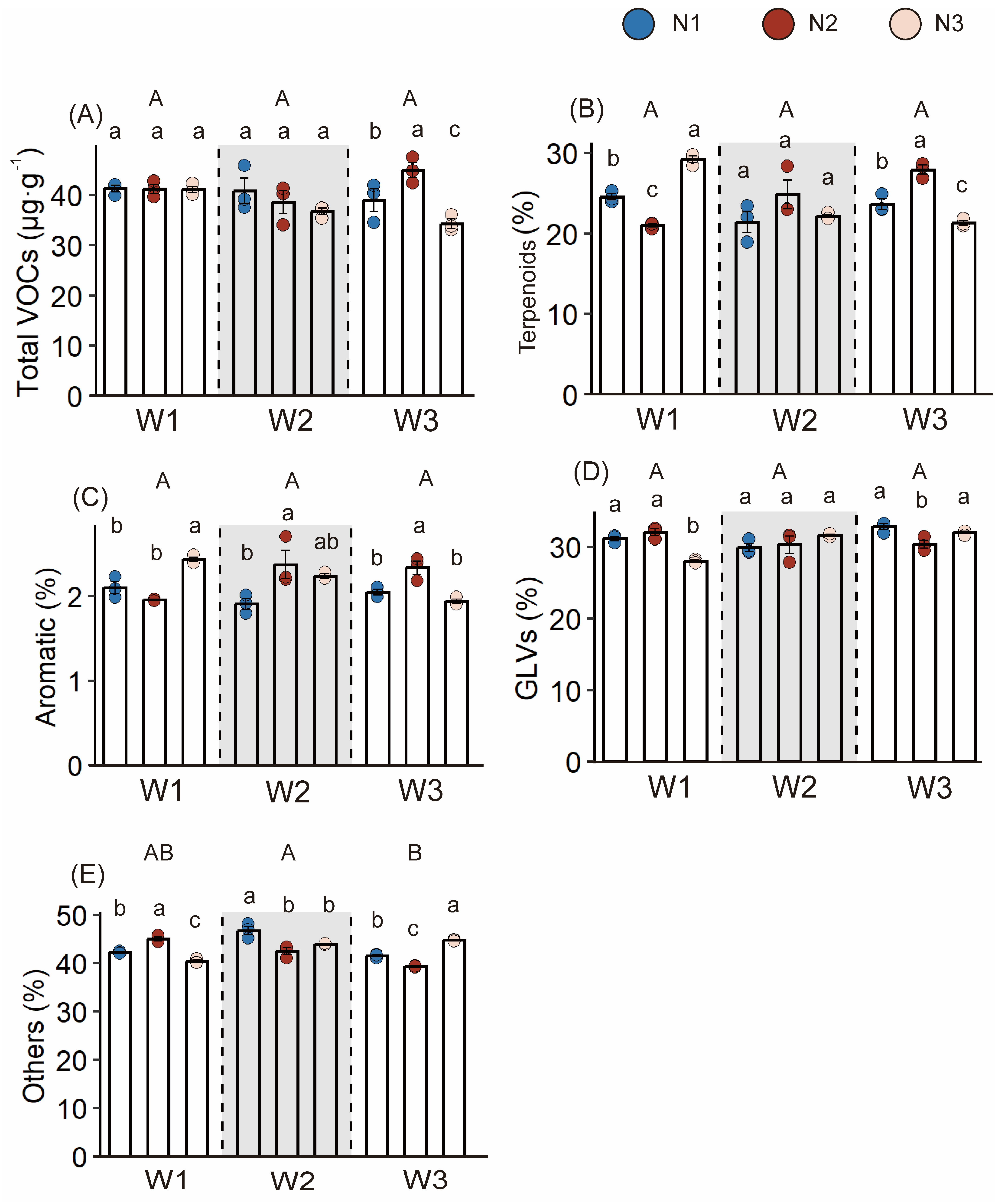

3.2. Response of Volatile Organic Compounds in Fresh Tea Leaves to Different Water and Nitrogen Treatments

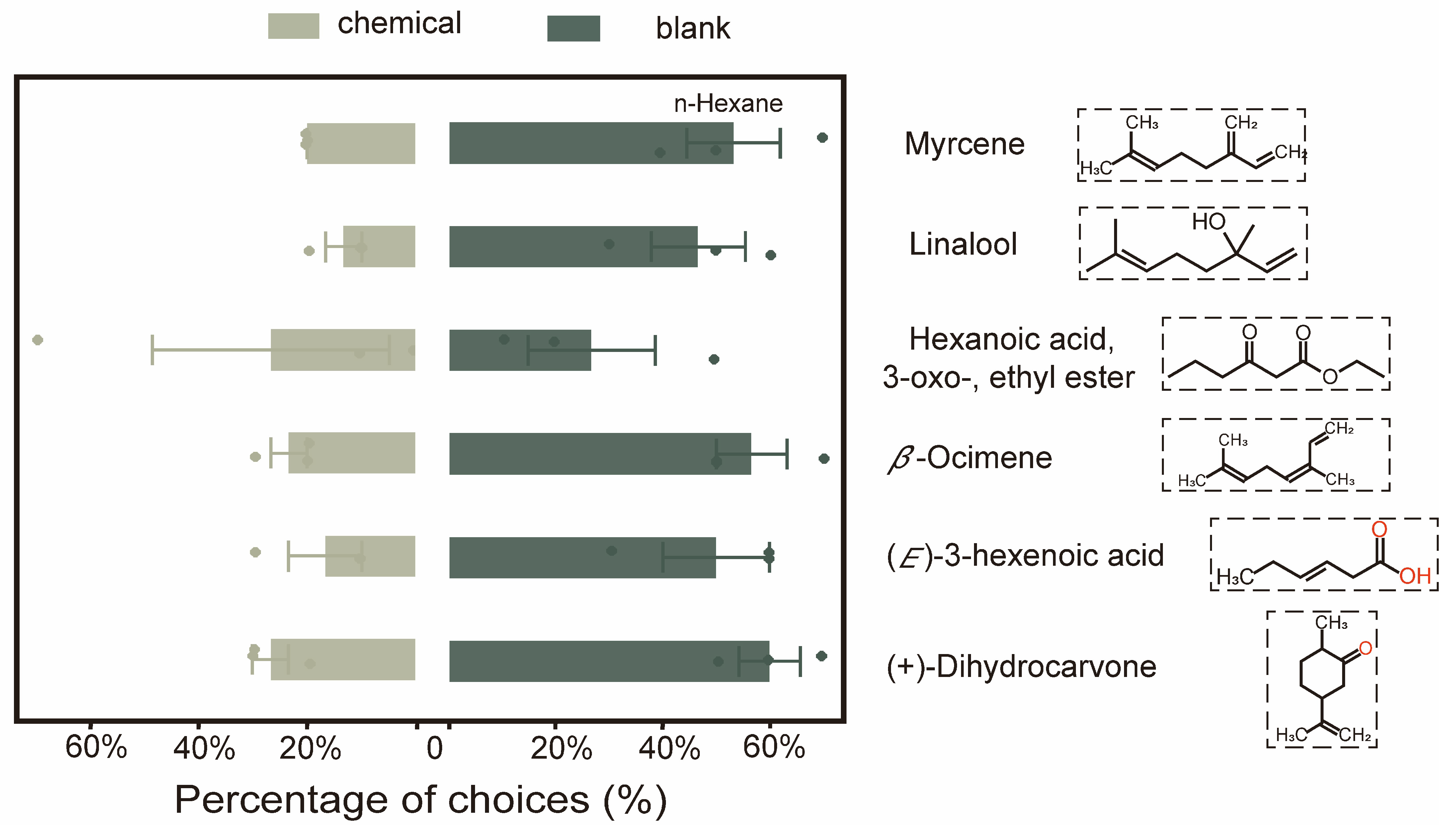

3.3. Verification of the Behavioral Response of Ectropis grisescens to Specific Volatile Compounds

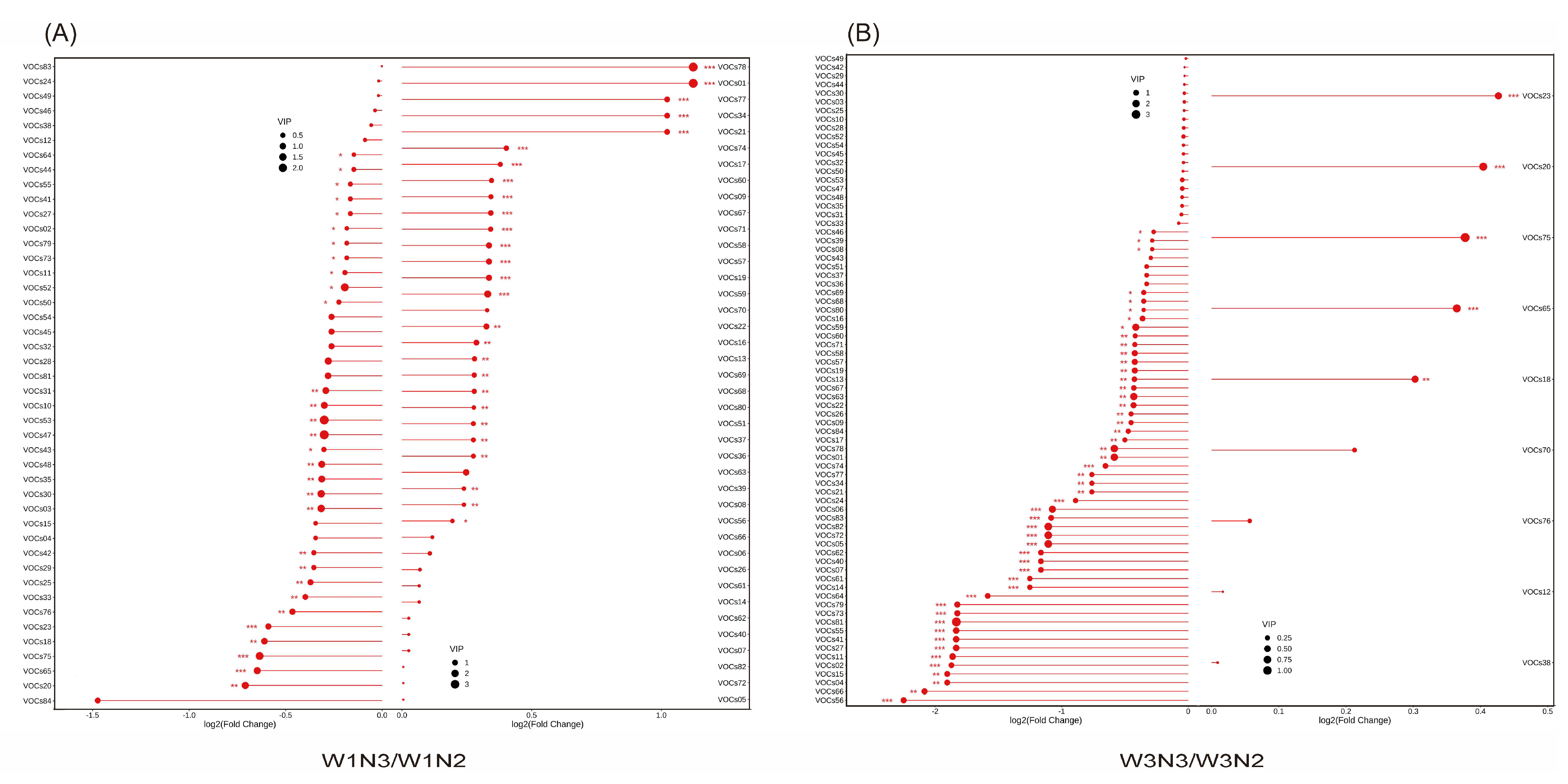

3.3.1. Screening of Specific Volatile Compounds Affecting the Behavioral Preference of E. grisescens

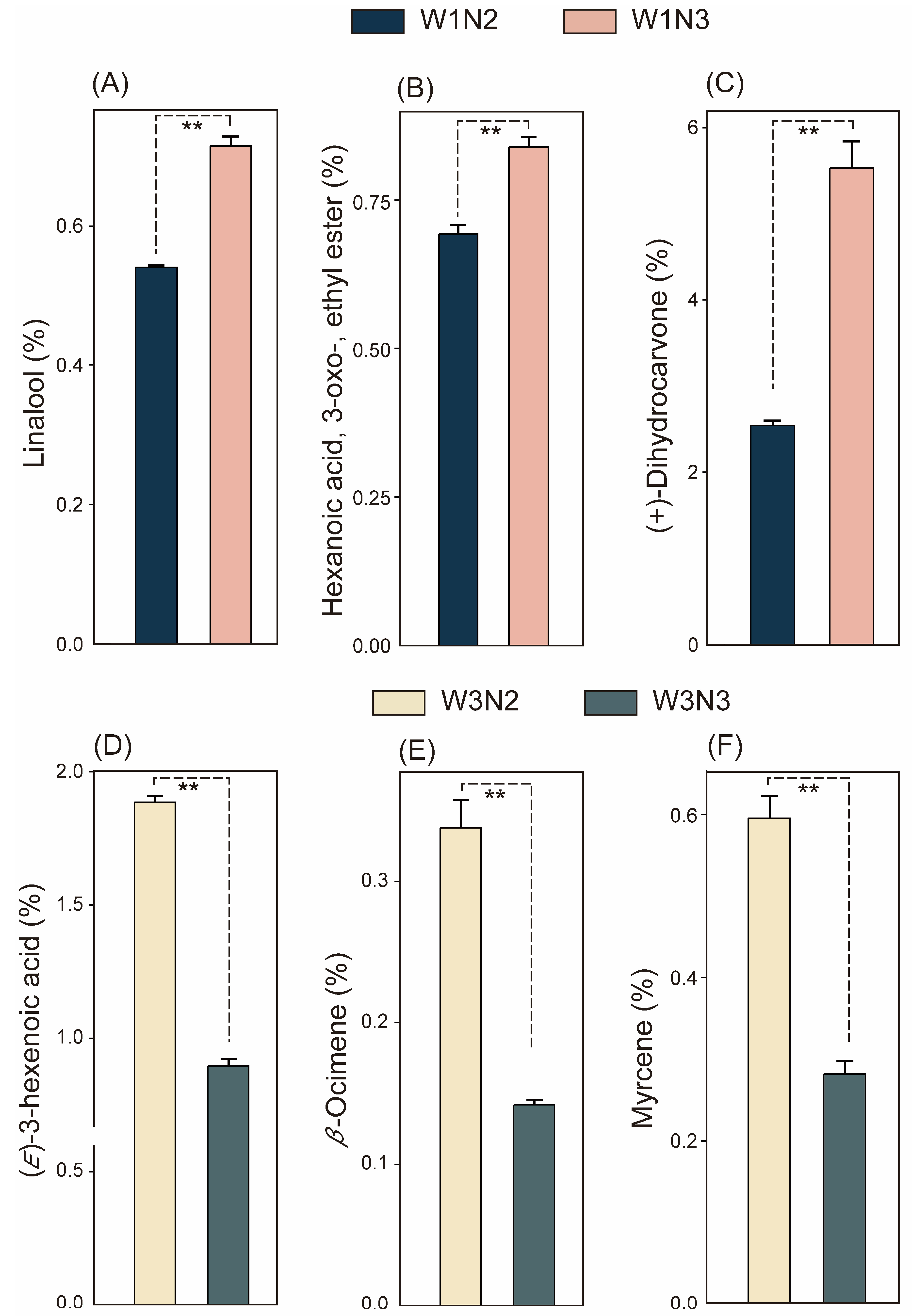

3.3.2. Verification of the Effects of Specific Volatile Compounds on the Behavioral Response of E. grisescens

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agbazo, M.; N’Gobi, G.K.; Alamou, E.; Kounouhewa, B.; Afouda, A. Detection of hydrological impacts of climate change in Benin by a multifractal approach. Int. J. Water Resour. Environ. Eng. 2019, 11, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Legg, S. IPCC, 2021: Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Interaction 2021, 49, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Singh, V.P. Spatiotemporal patterns of precipitation regimes in the Huai River basin, China, and possible relations with ENSO events. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 2167–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, C.A.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Tigchelaar, M.; Battisti, D.S.; Merrill, S.C.; Huey, R.B.; Naylor, R.L. Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science 2018, 361, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, M.A.; Trowbridge, A.M.; Raffa, K.F.; Lindroth, R.L. Consequences of climate warming and altered precipitation patterns for plant-insect and multitrophic interactions. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Tea Day 2022: FA0 Underlines the Need for Greater Sustainability. Available online: http://www.fao.org (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Yang, F.; Li, B.B.; He, C.Y. Research progress on the mechanism of high temperature and drought effects on the growth and quality of tea tree. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2017, 45, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Yu, J. The effect of high temperature damage on tea production during July–August 2013 in Lishui. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2014, 30, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Fang, G.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Q.; Zhan, S. Chromosome-level genome reference and genome editing of the tea geometrid. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 21, 2034–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bai, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhan, S.; Xiao, Q. Transcriptomic analysis reveals insect hormone biosynthesis pathway involved in desynchronized development phenomenon in hybridized sibling species of tea geometrids (Ectropis grisescens and Ectropis obliqua). Insects 2019, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Cai, X.M.; Luo, Z.X.; Bian, L.; Xin, Z.J.; Liu, Y.; Chu, B.; Chen, Z.M. Geographical distribution of Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) and Ectropis obliqua in China and description of an efficient identification method. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Zhou, X.G.; Xiao, Q.; Tang, P.; Chen, X.X. The potential of Parapanteles hyposidrae and Protapanteles immunis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as biocontrol agents for the tea grey geometrid Ectropis grisescens (Lepidoptera). Insects 2022, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.M.; Cai, X.M.; Zhou, L.; Bian, L.; Luo, Z.X. Developments on tea plant pest control in past 40 years in China. China Tea 2020, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Lou, Y.R.; Tzin, V.; Jander, G. Alteration of plant primary metabolism in response to insect herbivory. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.X.; Wang, D.X.; Shi, W.X.; Weng, B.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Su, S.H.; Sun, Y.F.; Tan, J.F.; Xiao, S.; Xie, R.H. Nitrogen-mediated volatilisation of defensive metabolites in tomato confers resistance to herbivores. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3227–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veyrat, N.; Robert, C.A.M.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. Herbivore intoxication as a potential primary function of an inducible volatile plant signal. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Huang, P.; Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Lin, Y.W.; Hu, J.F.; Liu, X.G. Specific volatiles of tea plants determine the host preference behavior of Empoasca onukii. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1239237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, T.; Qian, X.; Du, W.; Gao, T.; Li, D.; Guo, D.; He, F.; Yu, G.; Li, S.; Schwab, W. Herbivore-induced volatiles influence moth preference by increasing the β-ocimene emission of neighbouring tea plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 3667–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Luo, Z.; Meng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chu, B.; Bian, L.; Li, Z.; Xin, Z.; Chen, Z. Primary screening and application of repellent plant volatiles to control tea leafhopper, Empoasca onukii Matsuda. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Shan, W.; Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Su, F.; Yang, Z.; Yu, X. Defensive responses of tea plants (Camellia sinensis) against tea green leafhopper attack: A multi-omics study. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cease, A.J.; Elser, J.J.; Ford, C.F.; Hao, S.; Kang, L.; Harrison, J.F. Heavy livestock grazing promotes locust outbreaks by lowering plant nitrogen content. Science 2012, 335, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Desneux, N.; Becker, C.; Larbat, R.; Le Bot, J.; Adamowicz, S.; Zhang, J.; Lavoir, A.V. Bottom-up effects of irrigation, fertilization and plant resistance on Tuta absoluta: Implications for integrated pest management. J. Pest. Sci. 2019, 92, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, W.J. Herbivory in relation to plant nitrogen content. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1980, 11, 119–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Han, W.H.; Xiong, Y.D.; Ji, S.X.; Du, H.; Chi, Y.J.; Chen, N.; Wu, H.; Liu, S.-S.; Wang, X.-W. Drought suppresses plant salicylic acid defence against herbivorous insects by down-regulating the expression of ICS1 via NAC transcription factor. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutbrodt, B.; Mody, K.; Dorn, S. Drought changes plant chemistry and causes contrasting responses in lepidopteran herbivores. Oikos 2011, 120, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Zhou, F.Y.; Liang, Y.F. Review on the measures of drought prevention and drought resistance in the tea garden. J. Guizhou Tea 2012, 40, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Bharalee, R.; Bhorali, P.; Das, S.K.; Bhagawati, P.; Bandyopadhyay, T.; Gohain, B.; Agarwal, N.; Ahmed, P.; Borchetia, S.; et al. Molecular analysis of drought tolerance in tea by cDNA-AFLP based transcript profiling. Mol. Biotechnol. 2013, 53, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Liu, C.; Liu, K. Aromatic constituents in fresh leaves of Lingtou Dancong tea induced by drought stress. Front. Agric. China 2007, 1, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, K.; Wang, J.; Ding, Z.T.; Wang, H.; Bi, C.H.; Zhang, Y.W.; Sun, H.W. Proteomic analysis of Camellia sinensis (L.) reveals a synergistic network in the response to drought stress and recovery. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 219, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debere, N.; Lemessa, F.; Urgessa, K.; Berecha, G. Influence of combined application of inorganic-N and organic-P fertilizers on growth of young tea plant (Camellia sinensis var. assamica) in humid growing area of SW Ethiopia. J. Agron. 2014, 13, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owuor, P.O.; Othieno, C.O.; Kamau, D.M.; Wanyoko, J.K.; Ng’etich, W.K. long term fertilizer use on high yielding clone s 15/10 tea: Yields. Int. J. Tea Sci. 2008, 7, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, S.; Ahmad, F.; Hamid, F.S.; Khan, B.M.; Khurshid, F. Effect of different nitrogenous fertilizers on the growth and yield of three years old tea (Camellia sinensis) plants. Sarhad J. Agric. 2007, 23, 907–910. [Google Scholar]

- Owuor, P.O.; Odak, J.A.; Mang’uro, L.O.; Wachira, F.N.; Cheramgoi, E. Influence of nitrogen fertilisation on red spider mites (Oligonychus coffeae Nietner) and overhead volatile organic compounds in tea (Camellia sinensis). Int. J. Tea Sci. 2017, 13, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, B.; Pang, Y.; Du, Z. Appropriate nitrogen form and application rate can improve yield and quality of autumn tea with drip irrigation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Liang, X. Analysis of China’s tea production, sales, lmport and export situation in 2023. China Tea 2024, 46, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, K.K.; Choudhary, A.K.; Kumari, P. Entomopathogenic fungi. In Ecofriendly Pest Management for Food Security; Elsevier: London, UK, 2016; pp. 475–505. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, P.; Yang, D.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, D.; Xu, H. Estimated assessment of cumulative dietary exposure to organophosphorus residues from tea infusion in China. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2018, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lv, S.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Meng, Q. Oolong tea made from tea plants from different locations in Yunnan and Fujian, China showed similar aroma but different taste characteristics. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.H.; Chen, H.; Ge, P.Z. The discussion about good quality origin and production techniques of Wuyi Chinese cassia tea. Acta Tea Sin. 2007, 4, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, L.; Chen, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Geng, S. Effects of low temperature stress on survival, reproduction and protective enzyme activities of Ectropis grisescens Warren 1894 (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). Pak. J. Zool. 2024, 57, 1003–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.J.; Ma, Z.Y.; Qi, J.G.; Zou, Y.J.; Li, M.J. Effects of drought stress on nitrogen uptake and utilization of Malus hupehensis at different growth stages. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2023, 38, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, C.; Chen, X.H.; Lin, W.J.; Hu, H.N.; Wu, L.Q. Nitrogen balance status and greenhouse gas mitigationpotential in typical Oolong tea production areas. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2020, 37, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, J.; Teng, D.; Huang, X.; Lv, B.; Zhang, H.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Y. Overexpressing a cotton terpene synthase for (E)-β-ocimene biosynthesis in Nicotiana tabacum to recruit the parasitoid wasps. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, P.R.; Santiago, A.N.; Sance, M.M.; Peralta, I.E.; Carrari, F.; Asis, R. Neuronal network analyses reveal novel associations between volatile organic compounds and sensory properties of tomato fruits. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Wickham, H. Programming with ggplot2. In Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.; Yang, Z.; Baldermann, S.; Sato, Y.; Asai, T.; Watanabe, N. Herbivore-induced volatiles from tea (Camellia sinensis) plants and their involvement in intraplant communication and changes in endogenous nonvolatile metabolites. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 13131–13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.D.; Maudhuit, A.; Pascual-Villalobos, M.J.; Poncelet, D. Development of formulations to improve the controlled-release of linalool to be applied as an insecticide. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, J.; Wang, P.; Du, J.; Peng, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Perilla frutescens repels and controls Bemisia tabaci MED with its key volatile linalool and caryophyllene. Crop Prot. 2024, 184, 106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, F.; Li, Y.; Lu, F.; Wang, B.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, D.; Huang, M.; Wang, F. Impact of mild field drought on the aroma profile and metabolic pathways of fresh tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves using HS-GC-IMS and HS-SPME-GC-MS. Foods 2024, 13, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhao, M.; Gao, T.; Jing, T.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; Schwab, W.; Song, C. Amplification of early drought responses caused by volatile cues emitted from neighboring tea plants. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.L.; Yue, X.F.; Zhao, X.F.; Zhao, H.; Fang, Y.L. Physiological, micro-morphological and metabolomic analysis of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) leaf of plants under water stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 130, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copolovici, L.; Kannaste, A.; Remmel, T.; Niinemets, Ü. Volatile organic compound emissions from Alnus glutinosa under interacting drought and herbivory stresses. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 100, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, O.; Singh, A.; Bista, P.; Angadi, S.; Ghimire, R. Compost addition improves soil water storage and crop water productivity in cover crop integrated sorghum production system under a limited irrigation management. Irrig. Sci. 2025, 43, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.C.; Freschi, L.; Sodek, L. Nitrogen metabolism and translocation in soybean plants subjected to root oxygen deficiency. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 66, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü. Mild versus severe stress and BVOCs: Thresholds, priming and consequences. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, M.; Ding, S.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Meng, X.; Chen, S.; Gao, R.; Sun, W. Comprehensive characterization of volatile terpenoids and terpene synthases in Lanxangia tsaoko. Mol. Hortic. 2025, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, P.L.C.; De-La-Cruz-Chacón, I.; Sousa, M.C.; Vieira, M.A.R.; Campos, F.G.; Marques, M.O.M.; Boaro, C.S.F.; Ferreira, G. Effect of nitrogen sources on photosynthesis and biosynthesis of alkaloids and leaf volatile compounds in Annona sylvatica A. St.-Hil. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormeo, E.; Fernandez, C. Effect of soil nutrient on production and diversity of volatile terpenoids from plants. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2012, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomescu, D.; Şumălan, R.; Copolovici, L.; Copolovici, D. The influence of soil salinity on volatile organic compounds emission and photosynthetic parameters of Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties. Open Life Sci. 2017, 12, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzika, R.M.; Pregitzer, K.S. Effect of nitrogen fertilization on leaf phenolic production of grand fir seedlings. Trees 1992, 6, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainulainen, P.; Utriainen, J.; Holopainen, J.K.; Oksanen, J.; Holopainen, T. Influence of elevated ozone and limited nitrogen availability on conifer seedlings in an open-air fumigation system: Effects on growth, nutrient content, mycorrhiza, needle ultrastructure, starch and secondary compounds. Glob. Change Biol. 2000, 6, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, A.; Allmann, S.; Mirabella, R.; Haring, M.A.; Schuurink, R.C. Green leaf volatiles: A plant’s multifunctional weapon against herbivores and pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 17781–17811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghari, S.J.; Wahocho, N.A.; Laghari, G.M.; Laghari, A.H.; Bhabhan, G.M.; Talpur, K.H.; Bhutto, T.A.; Wahocho, S.A.; Lashari, A.A. Role of nitrogen for plant growth and development: A review. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2016, 10, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Ma, Y.; Xie, M.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, D. Rectal bacteria produce sex pheromones in the male oriental fruit fly. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 2220–2226.E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firn, R. Nature’s Chemicals: The Natural Products That Shaped Our World; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mauch-Mani, B.; Baccelli, I.; Luna, E.; Flors, V. Defense priming: An adaptive part of induced resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Tao, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, J.; Wang, L. The plant terpenes DMNT and TMTT function as signaling compounds that attract Asian corn borer (Ostrinia furnacalis) to maize plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 2528–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addesso, K.M.; McAuslane, H.J. Pepper weevil attraction to volatiles from host and nonhost plants. Environ. Entomol. 2009, 38, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedlmeier, M.; Ghirardo, A.; Wenig, M.; Knappe, C.; Koch, K.; Georgii, E.; Dey, S.; Parker, J.E.; Schnitzler, J.P.; Vlot, A.C. Monoterpenes support systemic acquired resistance within and between plants. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1440–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Physicochemical Property | Value |

|---|---|

| SOC | 14.34 ± 1.01 g kg−1 |

| Soil-TP | 0.51 ± 0.01 g kg−1 |

| Soil-TN | 1.25 ± 0.52 g kg−1 |

| Soil-TK | 8.2 ± 1.25 g kg−1 |

| AP | 6.19 ± 0.85 mg kg−1 |

| AK | 230.14 ± 10.96 mg kg−1 |

| AN | 157.01 ± 3.83 mg kg−1 |

| pH | 5.11 ± 0.36 |

| EC | 13.2 ± 1.13 μS cm−1 |

| VOC Type | Different Water and Nitrogen Treatments | |

|---|---|---|

| W1N2-W1N3 | W3N2-W3N3 | |

| Terpenoids | 5 compounds: (+)-Dihydrocarvone, Linalool, Cyclohexanol, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethylidene)-, p-Menth-2-en-7-ol, cis-, cis-Dihydrocarvone | 25 compounds: (+)-Dihydrocarvone, 2,6-Octadienal, 3,7-dimethyl-, (E)-trans-beta-Ocimene, 1,3,6-Octatriene, 3,7-dimethyl-, (Z)-Neral, Cyclohexanol, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethylidene)-, Cyclohexanol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)-, 1,3,7-Octatriene, 3,7-dimethyl-, β-Ocimene, γ-Terpinene, Ascaridole, Carvone oxide, trans-Linalool, p-Menth-2-en-7-ol, cis-Cyclohexene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethylidene)-, Carvone oxide, cis-Geraniol, Myrcene, 7-Octen-4-ol, 2-methyl-6-methylene-, (S)-Furan, 3-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-, 2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-7-one, 1,3,3-Trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2- One, D-Fenchone, L-Fenchone; |

| Aromatics | 4 compounds: Benzene, (methylthio)-Benzyl alcohol, Benzeneethanamine. 2-Phenylpropionaldehyde; | |

| GLVs | 5 compounds: 2-Decenal, (E)-3-Hexen-1-ol, acetate, (E)-3-Hexenoic acid, (E)-2-Hexen-1-ol, acetate, (E)-3-Hexen-1-ol, acetate, (Z)- | |

| Other Compounds | 1 compound: Hexanoic acid, 3-oxo-, ethyl ester | 10 compounds: 1-Cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, 4-(1-methylethenyl)-, (S)-Pyrazine, 3-butyl-2,5-dimethyl-, Pyrazine, trimethyl-Pyrazine, 2-butyl-3,5-dimethyl-Pyrazine, 5-butyl-2,3-dimethyl-Pyridine, 5-ethyl-2-methyl-Butyl angelate, 1-Undecyn-4-ol, trans, trans-Hexa-2,4-dienyl acetate, Hydroxylamine, O-decyl- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, W.; Shi, Q.; Yin, C.; Li, D.; Cai, P.; Wang, J.; Jin, S. Water and Nitrogen Regulation of Tea Leaf Volatiles Influences Ectropis grisescens Olfaction. Agronomy 2026, 16, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010018

Xie W, Shi Q, Yin C, Li D, Cai P, Wang J, Jin S. Water and Nitrogen Regulation of Tea Leaf Volatiles Influences Ectropis grisescens Olfaction. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Wei, Qiumei Shi, Chuanhua Yin, Dongliang Li, Pumo Cai, Jizhou Wang, and Shan Jin. 2026. "Water and Nitrogen Regulation of Tea Leaf Volatiles Influences Ectropis grisescens Olfaction" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010018

APA StyleXie, W., Shi, Q., Yin, C., Li, D., Cai, P., Wang, J., & Jin, S. (2026). Water and Nitrogen Regulation of Tea Leaf Volatiles Influences Ectropis grisescens Olfaction. Agronomy, 16(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010018