1. Introduction

Soil organic carbon (SOC) constitutes the largest carbon reservoir on Earth [

1]. As one of the three major terrestrial ecosystems, agricultural ecosystems account for only 8–10% of terrestrial soil carbon stocks but represent the most active carbon pool in the global carbon cycle [

2]. Agricultural ecosystems are strongly influenced by human activities and can be effectively regulated over relatively short timescales. However, considerable uncertainties remain in estimating soil carbon stocks owing to regional heterogeneity, diverse cropping patterns, and variable management practices. Population growth, climate change, and unsustainable cropping practices pose substantial risks of soil organic carbon depletion [

3]. For instance, unsustainable tillage practices may reduce farmland organic carbon by 30–60%, but 60–70% of the lost carbon can be re-sequestered through improved farming methods such as organic matter restoration and reduced tillage intensity [

4]. Therefore, accurate quantification of SOC dynamics in agroecosystems and elucidation of their driving mechanisms are of great theoretical and practical importance for predicting carbon storage potential, ensuring stable food production, and promoting sustainable agricultural development [

5].

Cotton is globally recognized as an economically important crop, primarily cultivated in sandy drylands and saline coastal regions, where it frequently encounters soil salinization stress. Globally, approximately 833 million hectares (about 8.7% of the Earth’s surface) of arable land are affected by salinization [

6,

7], and the problem is particularly severe in Xinjiang, where 37.7% of cultivated land is salinized [

8]. Although cotton shows strong salt tolerance and is regarded as a crop suitable for saline–alkali soil restoration [

9], global warming and climate-induced droughts have caused periodic resalinization, further aggravating soil salinization [

10]. Oasis processes driven by agricultural activities—such as cultivation, irrigation, and fertilization—combined with regional salinization, often reduce inputs of soil organic matter and external carbon. These processes affect soil aggregate formation and stability, thereby influencing SOC dynamics. Although previous studies have shown that the addition of plant residues or fertilizers can effectively replenish or enhance SOC sequestration [

11], systematic research on the long-term stability of soil carbon pools in continuous cotton systems and on the regulatory role of straw return in carbon cycling remains limited. These scientific issues warrant urgent investigation.

Although soil carbon is fundamental to soil health and climate change mitigation, its dynamic behavior remains insufficiently understood. Accurate and up-to-date mapping of SOC is essential for effective land management and alignment with international environmental initiatives. Currently, major approaches for SOC estimation include statistical methods, process-based modeling, and digital soil mapping, each characterized by inherent limitations. For instance, digital soil mapping can overcome data limitations and has been widely applied, but it suffers from information lag and limited capacity to capture dynamic changes [

12]. Process-oriented (PO) models, developed based on a comprehensive understanding of SOC cycling and its interactions with environmental factors, are widely used owing to their ability for temporal extrapolation and multi-scenario simulation. Representative process-based models include RothC, EPIC, Century, and DNDC [

13,

14,

15]. By simulating biogeochemical processes—including soil organic matter decomposition, synthesis, transformation, and carbon–nutrient cycling—these models can more accurately represent SOC dynamics over time. These models outperform machine learning (ML) algorithms in representing temporal variations in SOC [

16,

17,

18]. Among them, the RothC model, as a classic process-based SOC model, has a core advantage in partitioning soil carbon into corresponding pools, enabling precise simulation of the “decomposition–transformation–sequestration” process of SOC under saline stress in arid regions. Furthermore, compared to the EPIC model, the key driving parameters required by the RothC model (such as air temperature, crop residue input) can be obtained from publicly available meteorological datasets and regional statistical data, making it suitable for large-scale, long-term SOC simulation needs. As a well-known process-based model, the RothC model has been extensively validated in agricultural ecosystem studies across diverse regions worldwide [

19]. However, its applicability to saline–alkali soils in arid regions requires further improvement.

Owing to its unique geographical conditions, Xinjiang has developed into the world’s largest region practicing drip irrigation agriculture [

20]. Despite the widespread adoption of drip irrigation in Xinjiang, soil salinity in cotton fields remains difficult to eliminate completely. Moreover, with the prolonged use of subsurface drip irrigation, salinization problems related to water-saving irrigation practices have become increasingly evident [

20]. In the context of intensifying global soil salinization, accurate quantification of the spatiotemporal patterns and spatial differentiation mechanisms of SOC in salinized cotton fields of Xinjiang—while ensuring cotton yield and quality—has important implications for advancing understanding of soil carbon cycling in arid oasis ecosystems, evaluating soil nutrient supply capacity, and assessing carbon sequestration potential. Therefore, this study integrates multi-source datasets and conducts regional-scale simulations using the RothC model, with the following three objectives:

To incorporate salinity adjustment factors and vegetation carbon decomposition indices to enhance the RothC model, thereby improving the accuracy of SOC simulations in salinized cotton fields;

To reveal the spatiotemporal distribution patterns and long-term trends of SOC in Xinjiang’s cotton fields from 1980 to 2022 based on the improved model;

To identify the key drivers of SOC spatial variation, elucidate single- and multi-factor interactions, and provide theoretical and practical support for soil carbon pool management and sustainable agricultural development in arid cotton-growing regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Xinjiang is situated in northwestern China (73°32′–96°21′ E, 34°22′–49°33′ N). The region’s topography is defined by “three mountain ranges flanking two basins,” with the Tianshan Mountains running across the center, naturally dividing Xinjiang into Southern and Northern regions. Located deep within the Eurasian continent, Xinjiang exhibits a distinctive temperate continental climate, with low precipitation, high evaporation, marked diurnal temperature fluctuations, and abundant sunshine. Mean annual precipitation ranges from 170 to 177 mm across Xinjiang, with northern areas receiving 100–200 mm and southern regions only 25–98 mm [

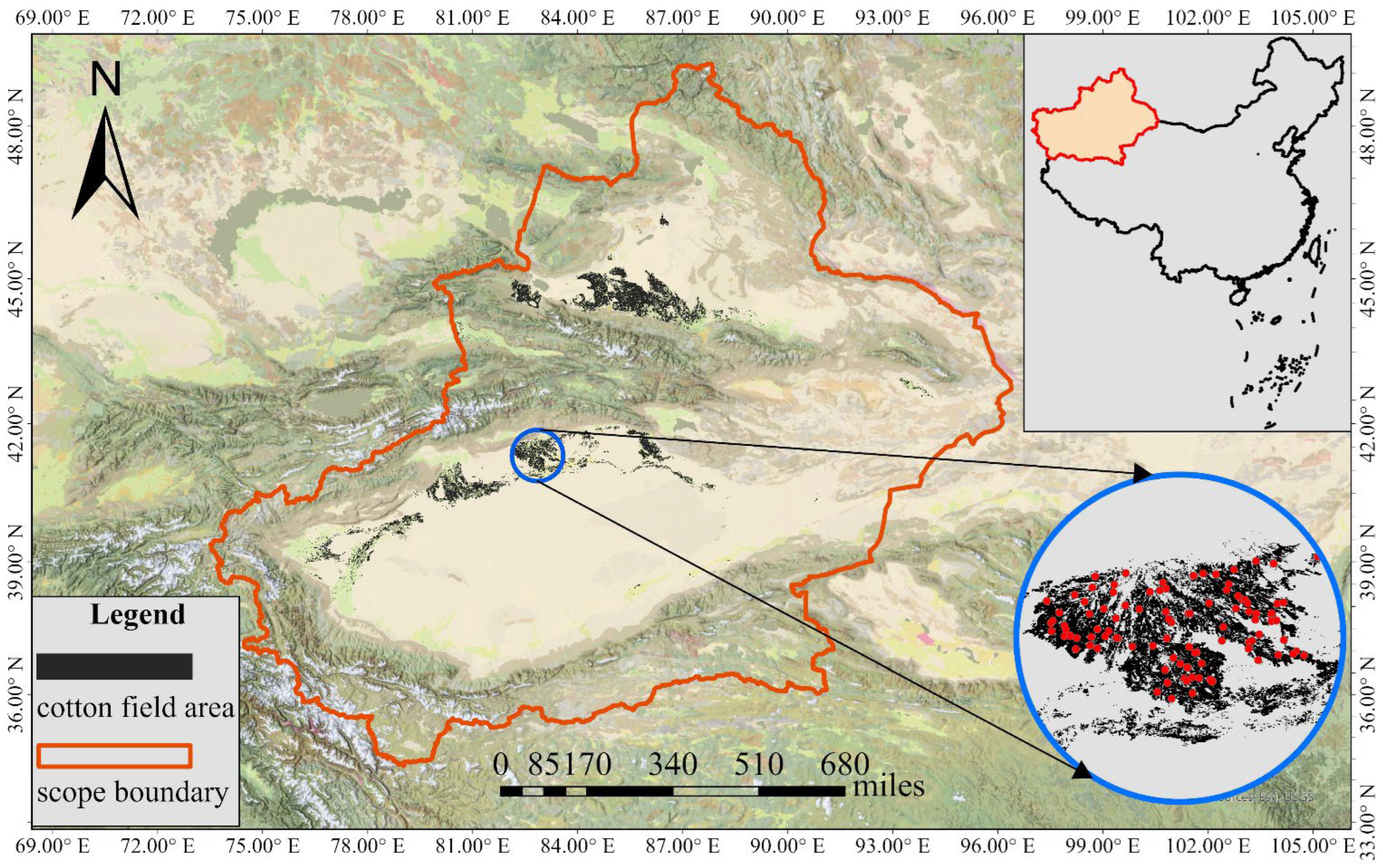

21]. This climate results in a landscape of “abundant solar and thermal resources coupled with limited water availability,” with annual sunshine hours of 2500–3500 and a frost-free period of 150–250 days. Located at 30°–45° N, the same latitude as Spain and France, Xinjiang falls within a prime crop cultivation zone, providing inherent advantages for specialty agriculture. Cotton has become the dominant crop in the region, as shown in

Figure 1, where black areas denote cotton field distribution in Xinjiang.

2.2. RothC Model Improvement for Cotton Field SOC Simulation

The RothC model is a classical process-based mechanistic model for simulating dynamic SOC changes and is widely applied in carbon cycle research across agriculture, ecology, and related disciplines. Developed from long-term monitoring data at the Lausanne Experimental Station, the model simulates organic carbon turnover in non-waterlogged topsoil and has been extensively validated in SOC simulation studies across diverse agricultural landscapes [

22]. Within the RothC framework, soil carbon is partitioned into five pools: Decomposable Plant Material (DPM), Resistant Plant Material (RPM), Microbial Biomass Carbon (BIO), Humic Organic Carbon (HUM), and Inert Organic Matter (IOM). Depending on vegetation type, the model allocates input plant residues to the DPM and RPM pools using a predefined DPM/RPM ratio. Carbon in these pools decomposes into BIO, HUM, and CO

2. The IOM pool, representing inert carbon, does not participate in active carbon cycling. Decomposition in each model compartment, except IOM, follows first-order exponential kinetics. The decomposition processes and monthly residual carbon stocks for each compartment are calculated using the following equation:

Here,

denotes the initial carbon pool quantity (t C/ha) for a specific pool;

,

, and

denote rate adjustment factors for temperature, moisture, and plant residue retention, respectively;

is the monthly decomposition rate constant for the pool,

is the number of time steps (months), and

is the monthly residual carbon in the pool. Because the RothC model was originally developed for non-salinized soils and does not account for salinity effects on carbon turnover, two targeted modifications were introduced in this study to accurately simulate SOC dynamics in cotton fields under salinized conditions. Soil salinity modifies microbial habitats via osmotic stress, thereby influencing SOC decomposition and carbon pool transformation processes. First, following the model’s carbon decomposition framework and based on Setia et al. [

23], a salinity rate modifier (

) was incorporated into the decomposition process. This salinity stress coefficient quantifies the regulatory effect of soil salinity on SOC decomposition. The modified decomposition equation (Equation (2)) is expressed as follows:

The salinity adjustment factor (d) is calculated using the following equation:

In the equation, Os represents the actual soil’s osmotic potential (MPa); ECmeans denotes the electrical conductivity (d S/m) of the 1:5 soil-water ratio extract at the reference moisture content; and denote the reference water content and actual water content, respectively. When Os = 0 MPa, the value of d is 1 (no salt influence), consistent with the baseline logic of the model correction. The corrected model synchronously regulates the decomposition rates of the original four active carbon pools (DPM, RPM, BIO, HUM) through the salt adjustment factor (d), enabling quantitative simulation of carbon turnover processes under salt stress.

Secondly, carbon input serves as a significant source for SOC in terrestrial ecosystems, and in Xinjiang’s saline–alkali regions, it is also influenced by salinity. Here, drawing upon research by Smith et al. [

24], we incorporate a vegetation carbon decomposition index into the model:

In the equation,

represents the plant input returned to the soil at a given soil salinity (

ECe), expressed as a proportion of plant input in non-saline-alkali land. This coefficient serves as an adjustment factor to be multiplied by the theoretical total plant carbon input at a specific study site, thereby calculating the actual total plant carbon input under salinity stress at that location. The slope value (

B, percentage yield reduction per unit salinity increase) and threshold (

A) reference the study by Shrivastava [

25]. Since our parameter optimization showed minimal variation (±0.5%) in slope

B and threshold

A for cotton fields with varying SOC, this study adopted the global average values for cotton fields:

B = 6.1% and

A = 4 dS/m.

2.3. Data Preparation for Regional-Scale Application of the RothC Model

To facilitate regional-scale application of the RothC model, multi-source driver data are required, encompassing three primary categories: dynamic environmental factors, carbon input data, and site-specific soil and management parameters. Specific data include straw return rates, fertilizer application rates, irrigation volumes, DPM/RPM ratios, soil cover, as well as soil clay content, soil depth, salinity index, and other relevant parameters. The sources of these data and the computational methods for implementing the model at the landscape scale are summarized as follows:

2.3.1. Inversion of Soil Salinity in Cotton Fields

Soil electrical conductivity (

ECe) is a key indicator of soil salinization and a critical parameter for refining the RothC model to quantify the influence of salt stress on SOC decomposition. To overcome the scarcity of high-precision, high-resolution spatial salinity data in the study area, this study leverages the improved model’s adaptability to salinity inputs, establishing the relationship between

ECe and carbon pool decomposition through salinity adjustment factors and obviating the need for high-frequency dynamic salinity measurements. Using a “multi-source covariate fusion + machine learning inversion” approach, spatial modeling of cotton field salinity was conducted on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform at a spatial resolution of 0.0025°. The types, specific indicators, and sources of each covariate are summarized in

Table 1.

The study integrated the multi-source covariates described above into a unified feature image. Using measured ECe as the target variable and the covariates as input features, feature values at sampling points were extracted, and valid samples were selected. This process ultimately produced a training dataset consisting of 918 valid samples. A random forest algorithm, with 500 decision trees, was employed to develop the salinity inversion model. Validation results indicated excellent model performance (MSE = 37.58, RMSE = 6.13 dS/m, R2 = 0.78), effectively capturing the spatial variability of ECe.

2.3.2. Meteorological Data Processing

Meteorological data were obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ERA5) for the period 1980–2022. The dataset includes monthly temperature, precipitation, and evaporation data. After downloading, the raw data were processed using the CDO (Climate Data Operators) version [2.0.3] (Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany) software. The MTCLIM mountain microclimate model was applied to downscale the spatial resolution of the raw data to 0.0025°.

2.3.3. Calculation of Plant Carbon Return Data

Soil carbon inputs include crop residues, roots, root nodule deposits, and farmyard manure in the current agricultural ecosystem. In this study, cotton-related carbon inputs were quantified regionally, using the sum of crop residues and root carbon as the baseline for carbon return in the RothC model. Cotton carbon inputs were partitioned into above-ground (crop residues) and below-ground (root system) components, calculated separately using the following equations:

Parameters and their values are defined as follows: : Economic yield of cotton per unit harvested area (kg/ha); : Dry matter fraction, set at 0.9; : Carbon proportion of cotton economic yield, set at 0.40; : Ratio of cotton residue to economic yield, set at 1.61; : Carbon fraction of cotton residues, set at 0.39; : Ratio of cotton roots to shoots, set at 0.06; : Carbon fraction of cotton roots, set at 0.41.

2.3.4. Spatialization of Other Input Data

Agricultural management practices are the primary anthropogenic drivers of SOC. Due to limited availability of field-scale management data, this study spatialized parameters under the assumption of “regional management practice homogeneity”. Fertilizer application rates and irrigation volumes were primarily obtained from the Xinjiang Statistical Yearbook (1980–2022), providing annual data for all 14 prefectures (cities) in Xinjiang. Fertilizer application was expressed as the combined equivalent of organic and chemical fertilizers, while irrigation volume was estimated from the actual irrigated cotton field area and total water supply. Considering the extensive large-scale cotton cultivation, uniform dissemination of agricultural technologies across regions, and relatively consistent climate and soil conditions within administrative units, we assumed that agricultural management practices (e.g., fertilization intensity, irrigation frequency) were uniform within each prefecture (city). Spatial distribution data for cotton fields were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7856467), representing the 2022 distribution. Considering the stability of cotton cultivation in the study region, potential fallow land in certain areas was disregarded.

2.4. Geodetector Method

The geodetector method computes a statistical measure (Q-value) to quantify the explanatory power of individual factors on the spatial variability of SOC. It identifies and quantifies the effects of multiple environmental factors on cotton field SOC, with particular emphasis on their interactions. Compared with traditional statistical methods, geodetector offers significant advantages in analyzing large-scale spatial data and complex interactions among variables. This method is especially suitable for our study, as it facilitates understanding the complex interactions among multiple factors potentially influencing SOC.

Considering that SOC in arid cotton fields is mainly influenced by climatic factors, human management, and soil properties, data on climate, agricultural practices, soil characteristics, and topography were collected to examine the spatial variation in SOC under the influence of these factors. After removing collinear variables, nine core drivers were selected for Geodetector analysis, encompassing both natural and anthropogenic factors (

Table 2). Using the natural breakpoint method, the variables were classified into five categories to represent intensity gradients, satisfying Geodetector’s requirement for categorical input.

2.5. Estimation of SOC in Cotton Fields Across Xinjiang Against a Salinization Background

The research process comprised four main steps: 1. Batch processing of 43 years of meteorological data was performed using the CDO software to obtain daily total precipitation, daily mean temperature, and other parameters for each location. 2. Using a Python-based batch processing approach (Python version [3.9.7]), the Mountainous Terrain-Climate Model was applied to downscale meteorological data to a spatial resolution of 0.0025° across 1,140,858 locations. 3. Assuming uniform human management practices within each administrative region, management data were compiled for 14 regions, and cotton field salinity data at 20-m resolution across Xinjiang were derived. 4. Using measured parameters, management data, and meteorological inputs, a Python loop program was developed to sequentially execute the RothC model at each location. This procedure simulated SOC at nearly 1,140,858 cotton field sites across Xinjiang from 1980 to 2022, producing spatiotemporal patterns of SOC at a spatial resolution of 0.0025°.

3. Results

3.1. Validation of Results

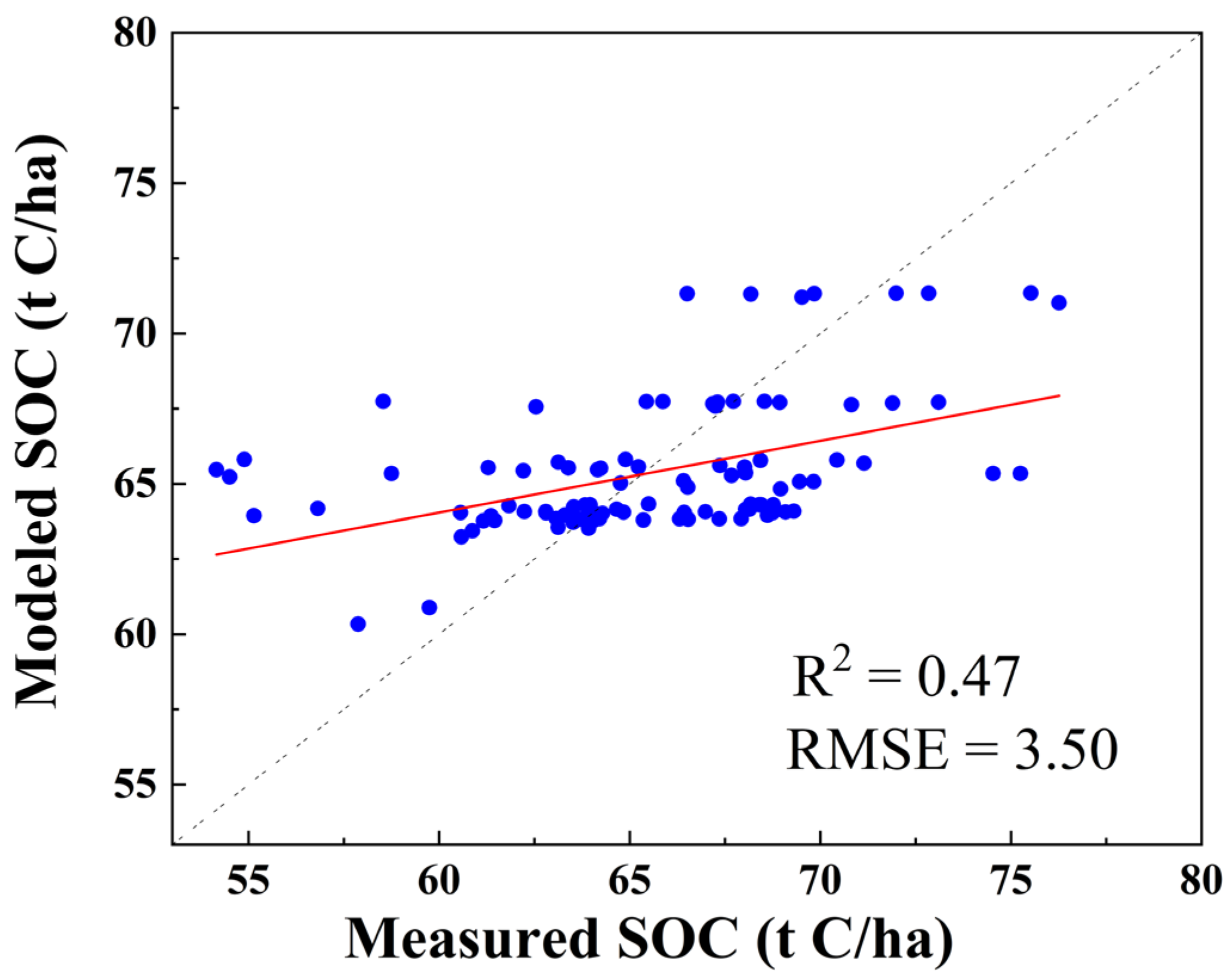

Field samples collected by the research team in the Weiku–Aksu region of Xinjiang (2016–2024) were used to validate the calibrated RothC model. The validation results indicated that the calibrated model effectively captured the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of SOC: the simulated values showed a strong correlation with the measured data, with a coefficient of determination R

2 of 0.47 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 3.5 t C/ha (

Figure 2). Although low validation metrics are common in regional-scale simulations due to spatial heterogeneity, the RMSE in this study accounted for only 5.8% of the regional average SOC stock (approximately 60 t C/ha), which falls within a reasonable error range. These results demonstrate that the optimized RothC model possesses reliable predictive capability for SOC variation and can effectively support macro-scale trend analysis.

3.2. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of SOC in Xinjiang Cotton Fields

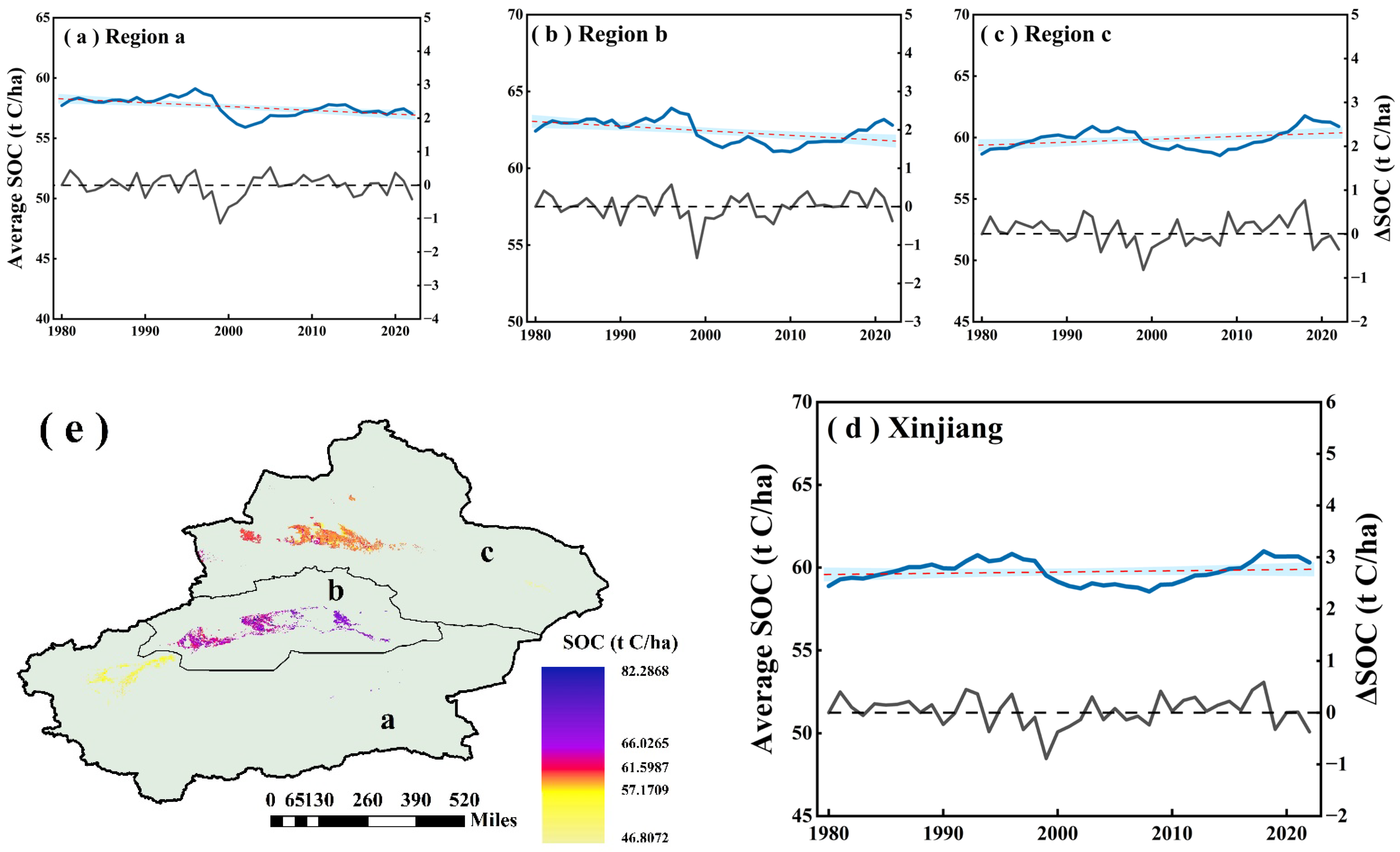

Based on simulated SOC results for Xinjiang cotton fields from 1980 to 2022, combined with spatial clustering and temporal trend analyses, SOC exhibited significant spatiotemporal differentiation over the 43-year period. Based on SOC content, the region was divided into three major core areas (

Figure 3), The division of core areas is intended to reveal how SOC spatial patterns are linked to regional natural and human-driven factors. The low-value region is located in southwestern Xinjiang (Region a), with an average SOC of 57.60 t/ha, ranging from 46.80 to 61.60 t/ha. Region b represents the high-value SOC zone, distributed along the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains, encompassing the Aksu oasis region. This foothill area exhibits a SOC range of 57.17–66.03 t/ha, with an average of 62.41 t/ha. Region c mainly covers transitional zones in central and northeastern Xinjiang, with SOC ranging from 56.60 to 61.50 t/ha and averaging 59.88 t/ha. Overall, the spatial distribution of SOC in Xinjiang shows a gradient from southwest to northeast. The Aksu region, south of the Tianshan Mountains, has the highest SOC values, whereas cotton fields in southwestern Xinjiang exhibit the lowest SOC accumulation. Other areas exhibit moderate SOC levels.

Over time, SOC content in Xinjiang cotton fields exhibited a fluctuating upward trend, increasing from 58.88 t C/ha in 1980 to 60.30 t C/ha in 2022. This corresponds to a cumulative increase of 1.42 t C/ha, with an average annual growth rate of 0.033 t C/(ha·year) and a linear fitting slope of 0.033 (p < 0.05). Over the 43-year period, SOC in cotton fields showed differentiated dynamics, characterized by an overall increase with localized regional declines. Region a (low-value zone) exhibited a significant decline, with a linear fitting slope of −0.0317 (p < 0.05), representing the largest decrease among the three regions. Region b (high-value zone) also showed a declining trend, with a linear slope of −0.0301 (p < 0.05), whereas Region c exhibited an increasing trend, with a linear slope of 0.0237 and a standard deviation of 0.84 t C/ha, indicating high temporal variability within this area. Overall, Xinjiang cotton fields display significant spatiotemporal coupling of SOC. The southern Tianshan Mountains region maintains high SOC with a slight decline and strong spatial stability. The southwestern low-SOC zone (Region a) has low initial content and continues to decline, highlighting a substantial risk of soil carbon pool degradation. The central transition zone (Region c) represents a potential area for future SOC enhancement.

3.3. Identification of Individual Factors Influencing SOC Variation in Cotton Fields of Arid Regions

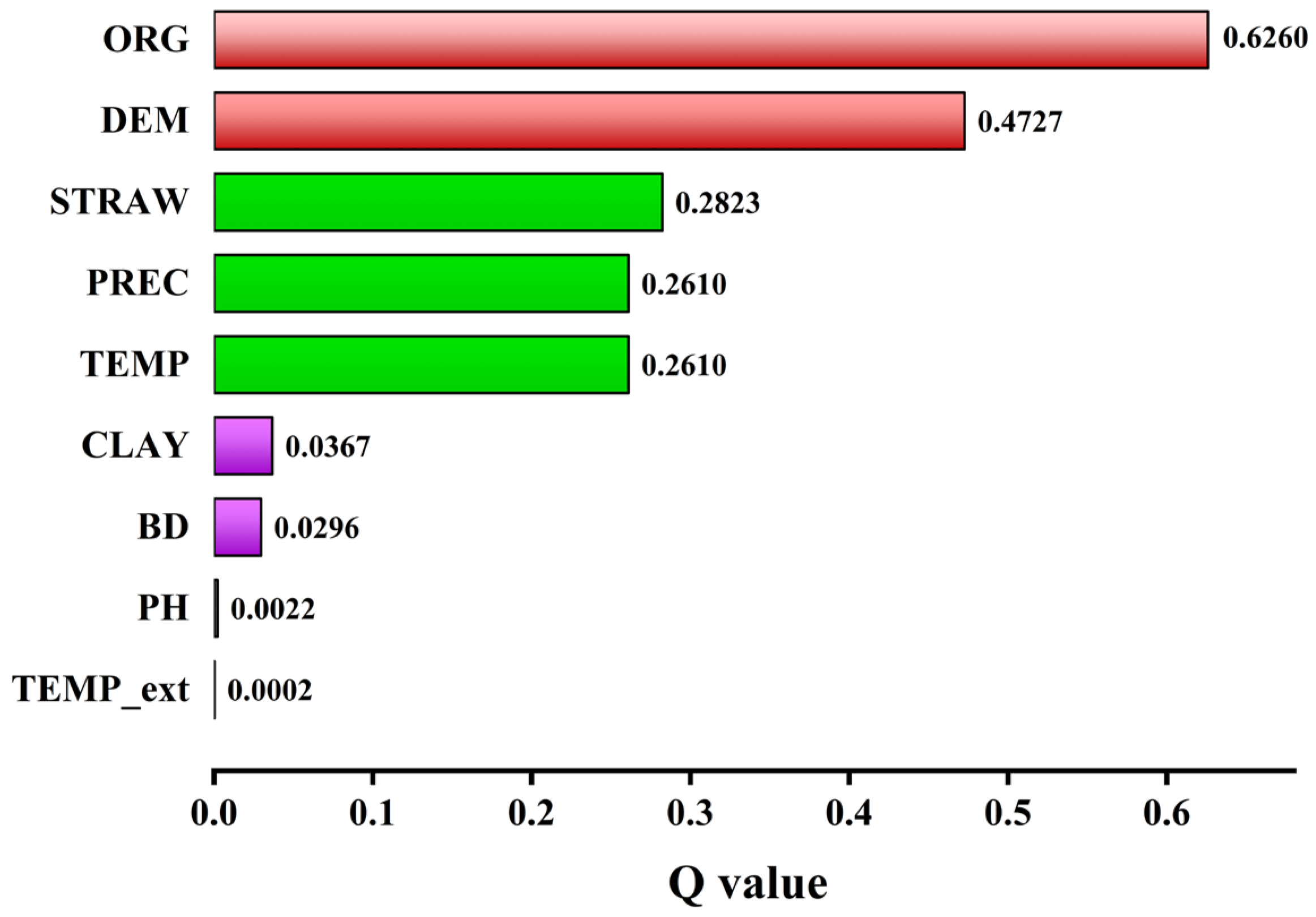

Geodetector analysis showed that the

p-values of all analyzed factors were below 0.05, with nine factors being statistically significant for the spatial variation in SOC in cotton fields (

Figure 4). The relative explanatory power (Q-value) of each factor quantifies its contribution to SOC spatial variation.

The results indicate that ORG (fertilization) and DEM, with Q-values above 0.4, are the primary drivers of spatial variation in SOC, jointly dominating this differentiation. Among these, ORG has an explanatory power of 0.626, making it the most critical factor. STRAW (straw return), PREC (annual precipitation), and TEMP (annual temperature) had Q-values between 0.2 and 0.3, indicating that they are secondary factors with moderate explanatory power for cotton field SOC. Conversely, CLAY (clay content), BD (bulk density), PH (pH), and TEMP_ext (extreme high temperature) all had Q-values below 0.04, indicating a minor influence on cotton field SOC. Among these, TEMP_ext had an explanatory power of only 0.0002, demonstrating negligible influence.

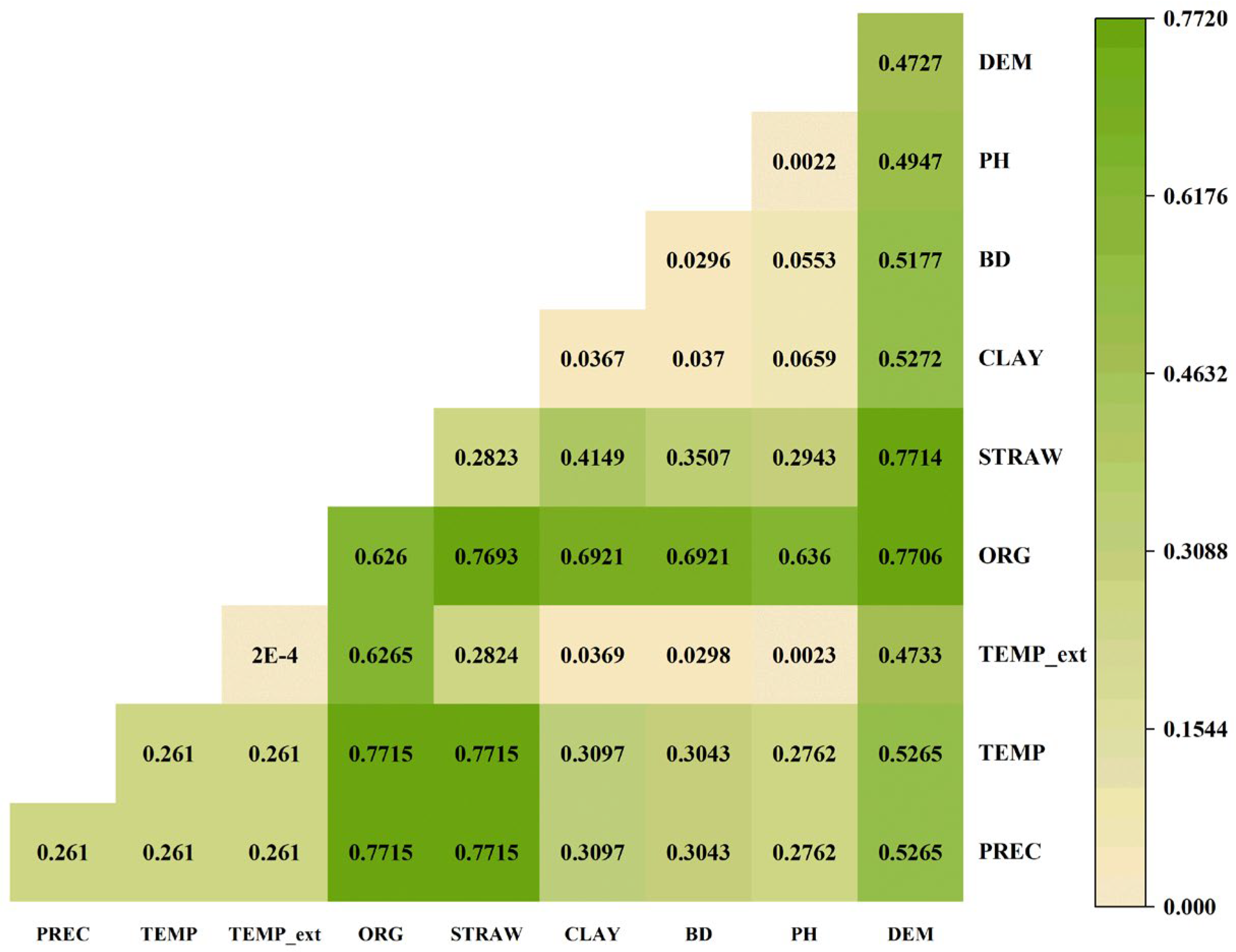

3.4. Identification of Interaction Factors Affecting SOC Variation in Cotton Fields of Arid Regions

The Geodetector Interaction Detector was used to assess the explanatory role of interaction factors in SOC spatial variation, characterizing the synergistic effects of various factor combinations. Based on single-factor explanatory power, interaction effects were classified into two types: synergistic enhancement and independent effects (

Table 3). Interactions among factors controlling SOC spatial variation in cotton fields predominantly showed synergistic enhancement. Only the PREC–TEMP, PREC–TEMP_ext, and TEMP–TEMP_ext factor combinations demonstrated independent effects. The convergence of most factor combinations enhanced their explanatory power for SOC spatial variation.

Geodetector interaction results indicate that synergistic effects between managed fertilization (ORG) and crop residue return (STRAW) with other factors amplify the spatial variation in SOC in cotton fields (

Figure 5). Combinations with the strongest interaction intensity include PREC–ORG, PREC–STRAW, TEMP–ORG, and TEMP–STRAW (all with Q-values of 0.7715), as well as STRAW–DEM (0.7714), ORG–DEM (0.7706), and ORG–STRAW (0.7693). The Q-values of these interactions, all close to 0.77, exceed the explanatory power of any individual factor. Other factor combinations show relatively low interactive explanatory power; for example, the Q-value for TEMP_ext–PH is 0.0023. Variation in factor interactions reflects the complex, multidimensional mechanisms driving the spatial differentiation of SOC in cotton fields.

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential Causes of Spatiotemporal Variations in Cotton Field SOC

Mechanistic model simulations indicate that spatiotemporal variations in SOC within cotton fields in arid Xinjiang are driven by the combined effects of climate, soil properties, and human management practices [

26]. Oasis regions south of the Tianshan Mountains rely on snowmelt and glacial runoff to compensate for the low precipitation, which ranges from 25 to 98 mm annually in southern Xinjiang. This creates favorable water and thermal conditions that promote cotton growth and sustain microbial activity. Increased soil moisture enhances microbial activity, accelerating organic carbon transformation and accumulation, thereby forming high-SOC zones in cotton fields [

27,

28]. In contrast, the southwestern region near the desert margin exhibits low SOC values due to limited precipitation and high evaporation. Deviations of precipitation and temperature from climatological averages typically reduce crop yields. Annual mean temperature affects organic carbon mineralization by regulating the soil thermal environment, thereby influencing the stability of soil carbon pools [

29]. Notably, the Q-value for growing season precipitation (PREC_g) was lower than that for annual precipitation, indicating that under irrigated conditions, annual precipitation distribution has a greater impact on SOC than seasonal precipitation. These findings further confirm the importance of rainfall distribution compared to seasonal totals. Intensive management practices in Xinjiang cotton fields ensure prolonged irrigation throughout the growing season, with some areas maintaining consistently moist soils. This practice substantially mitigates the effects of regional precipitation variability.

Soil properties regulate the spatial differentiation of SOC primarily through regional variations in carbon sequestration capacity. In water-limited (unsaturated) environments, fine-textured soils exhibit higher water retention (due to smaller pores and stronger capillary suction) and greater unsaturated hydraulic conductivity than coarse-textured soils [

30]. Our results support this finding: in the southwestern cotton-growing region (low-value zone), soils are predominantly sandy. Sandy soils have larger inter-particle voids and smaller specific surface areas, resulting in lower adsorption and sequestration capacities for organic carbon. In contrast, oasis areas south of the Tianshan Mountains have higher clay content. Clay particles form stable complexes with organic carbon. Additionally, the stable soil moisture, maintained by irrigation from snowmelt and glacial runoff, further enhances clay-mediated sequestration of organic carbon [

31]. This results in patchy SOC distribution, forming high-SOC core zones. Although soil texture significantly affects crop organic carbon [

30], the overall spatial variation in SOC in Xinjiang cotton fields shows a low Q-value for soil texture. This low explanatory power is attributed to the relative uniformity of soil properties in arid regions and the effects of continuous irrigation.

4.2. Effects of Management Practices on SOC in Cotton Fields

Agricultural production is subject to fluctuations influenced by human intervention, with arid-zone farming particularly dependent on intensive management. Our results indicate that fertilization (ORG, Q = 0.626) and straw incorporation (STRAW, Q = 0.2823) are key drivers regulating SOC accumulation and transformation in arid cotton fields [

32]. Straw incorporation replenishes the SOC pool by adding plant residues to the soil, thereby creating favorable conditions for SOC accumulation [

33,

34]. Decomposition releases active substances that improve soil aggregate structure and enhance water and nutrient retention [

35,

36]. Field investigations further showed that after cotton harvest and straw incorporation, farmers plant winter wheat. This practice may deplete nutrients released from straw decomposition and alter soil microbial communities, reducing the benefits of straw return. Fertilization (ORG), the most critical anthropogenic driver, effectively enhances organic carbon and soil quality [

37,

38]. This measure can not only directly input a large amount of organic carbon into the soil [

39] but also increase the diversity and richness of soil bacteria, which may further promote the decomposition of organic matter. For details, refer to the relevant study: [

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1285445].

In arid regions with harsh natural conditions, human activities are the primary drivers of spatial differentiation in SOC in Xinjiang cotton fields, with synergistic interactions with other factors amplifying their effects. This study found an overall upward trend in SOC, though both the low-value zone in the southwest (Region a) and the high-value zone along the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains (Region b) exhibited localized declines. The decrease in SOC in the southwestern low-value zone (Region a) is directly linked to the region’s persistently rising temperatures and limited irrigation availability. Observational data show that the region’s annual average temperature has increased by 1.2 °C over the past 40 years, significantly higher than the average increase across Xinjiang (0.8 °C) [

40], which accelerates the mineralization of soil organic matter. Concurrently, water resource constraints have led to insufficient irrigation, further limiting carbon inputs. These results indicate that SOC dynamics are the outcome of combined effects from natural climate stressors and human management interventions.

Our Geodetector analysis identifies fertilization as the primary driver of SOC spatial differentiation. This strong influence can be attributed to both direct and indirect mechanisms. Directly, fertilizers—particularly organic fertilizers—add substantial organic carbon inputs to the soil. Indirectly, and perhaps more importantly, fertilization alters the soil biological environment. As recent studies have indicated, fertilization can enhance the diversity and richness of soil bacterial communities [

41]. Additionally, the combination of cover crops and appropriate fertilization has been shown to be an effective conservation agriculture practice [

42]. Carbon released from straw decomposition, together with nutrients from fertilizers, provides energy for microorganisms and promotes soil aggregate formation, especially in low-biomass cropping systems such as cotton [

43]. Fertilization and straw incorporation not only replenish carbon pools but also synergistically modify soil properties and structure, increasing macroporosity [

44]. Healthy soil structure is essential for fertility and plant growth; our results indicate that crop responses to environmental stress largely depend on fertilizer application [

45]. Considering the carbon pool degradation risk in the low-SOC southwest region and the enhancement potential in moderate-SOC areas, we recommend the following strategies for the low-SOC zone: increase organic fertilizer application, raise the proportion of straw returned, and regulate soil moisture through irrigation. Future studies should investigate the combined effects of different organic fertilizer types and straw return rates. Integrating these findings with long-term field trials may offer more precise strategies for enhancing carbon pools in arid-region cotton fields.

4.3. Research Limitations and Uncertainty Assessment

This study simulated SOC dynamics in cotton fields across typical arid regions from 1980 to 2022 using an improved process-based model that integrated multi-source data and spatial downscaling techniques, while geographical detectors were applied to analyze spatial variation drivers. Nevertheless, several uncertainties persist: 1. Data Input Uncertainty: Although official statistical yearbooks were used to enhance credibility, the spatial processing of management data (fertilizer application rates and straw return rates) assumed uniform practices within administrative regions. The heterogeneity in farm size and actual management practices may lead to discrepancies between grid-scale parameters and field conditions, which could significantly influence the spatial variation patterns of simulated SOC. It should be supplemented that the input data for different regions (prefecture-level cities) have not been clearly defined, mainly due to the fact that some detailed agricultural management data of prefecture-level cities involve core local production statistical information, which has not been fully disclosed due to data confidentiality regulations, and the existing statistical system mostly takes prefecture-level cities as the basic unit, lacking more refined standardized public datasets. Additionally, due to the lack of high-resolution historical cotton field data, this study assumes stable cotton planting patterns for 1980–2022, ignoring potential small-scale historical expansion or contraction of cotton fields, which may introduce minor deviations to long-term SOC simulations despite the overall regional planting stability. 2. Insufficient Localization of Model Parameters: The regional parameters for salinity adjustment factors and vegetation carbon decomposition indices were not systematically calibrated based on field measurements specific to Xinjiang. Notably, the model did not fully account for variations in soil salt types across different cotton-growing areas or incorporate the spatial heterogeneity of cotton variety-specific salt tolerance traits. Additionally, limited sampling density in highly saline and remote regions constrained the spatial representativeness of these parameters, which may affect the simulation accuracy of the model under extreme environmental conditions. 3. Other Potential Sources of Error: Meteorological data may have incurred accuracy loss during the downscaling process. Furthermore, the assumption of ignoring fallow land dynamics in cotton field spatial distribution data could also introduce systematic bias.

Considering the aforementioned limitations and intrinsic characteristics of the mechanistic model, we recommend that future research focus on comprehensive model optimization. First, regarding the widely concerned uncertainty issue of large-scale simulation, future studies will improve reliability by constructing a multi-scale nested validation system, setting up refined observation units in core cotton-growing areas, and calibrating regional parameters with encrypted validation data of prefecture-level city divisions. Meanwhile, aiming at the unclear definition of input data in different regions, we will cooperate with local relevant departments to obtain partitioned management statistical data under the premise of complying with data confidentiality regulations, and combine UAV remote sensing and farmer sampling surveys to achieve accurate quantification of input data at the prefecture-level city scale. For data refinement, we suggest integrating high-resolution multispectral drone imagery with large-scale household survey data to construct spatially explicit models of field-level management parameters, including fertilizer application rates and straw return amounts. Developing a standardized model input database could mitigate the effects of data input uncertainties on SOC simulations. Furthermore, future studies should integrate multi-source historical land use datasets to reconstruct the dynamic spatial pattern of cotton cultivation from 1980 to 2022, and explore the impact of historical planting boundary changes on SOC temporal and spatial evolution, so as to further reduce the uncertainty of model simulation caused by static land use assumptions. Second, we recommend calibrating salinity adjustment factors and vegetation carbon decomposition indices via long-term, fixed-site trials across multiple cotton-growing regions. Calibration should incorporate salt types (e.g., chloride, sulfate) and cotton variety-specific salt tolerance traits. Localized optimization of model parameters would enhance the adaptability and reliability of the RothC model in saline-affected cotton fields.