Construction of a CFD Simulation and Prediction Model for Pesticide Droplet Drift in Agricultural UAV Spraying

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Numerical Simulation and Verification of the Rotor Wind Field

2.1.1. Numerical Simulation of the Rotor Wind Field

2.1.2. Intensity Test of the Rotor Wind Field

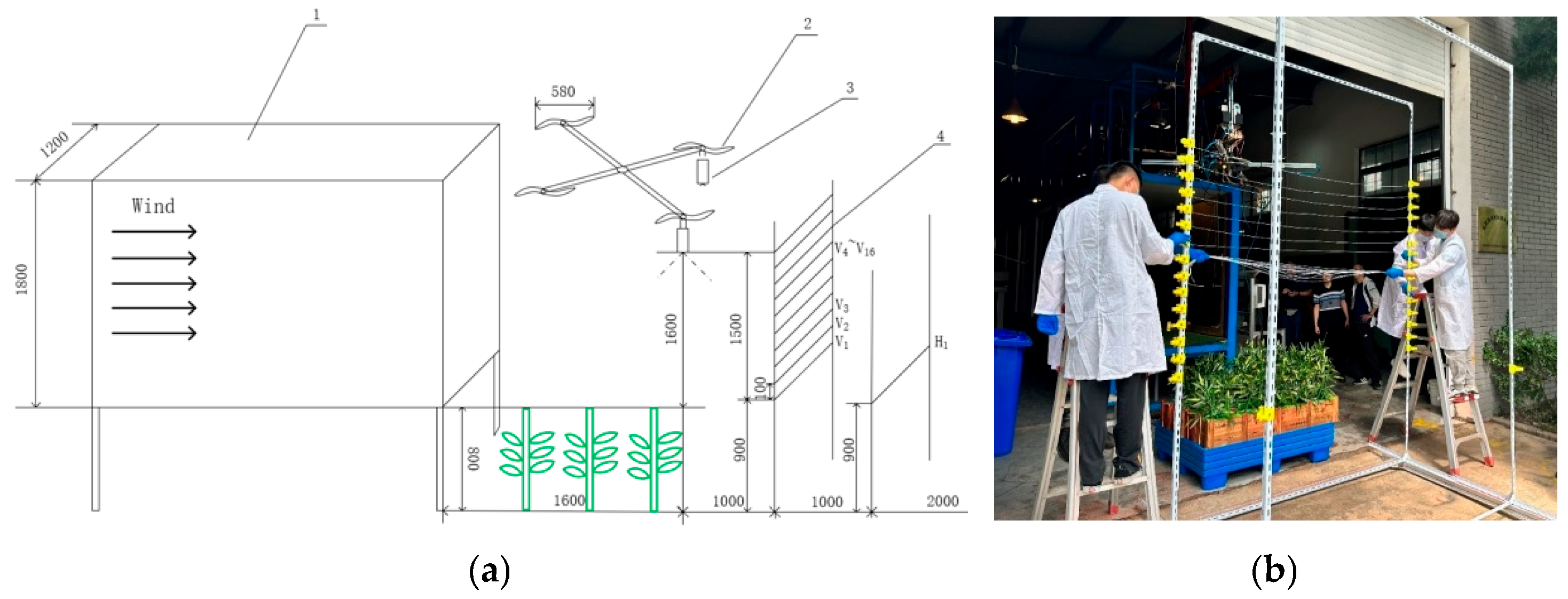

2.2. Droplet Drift Simulation and Wind Tunnel Test Under Coupled Wind Field

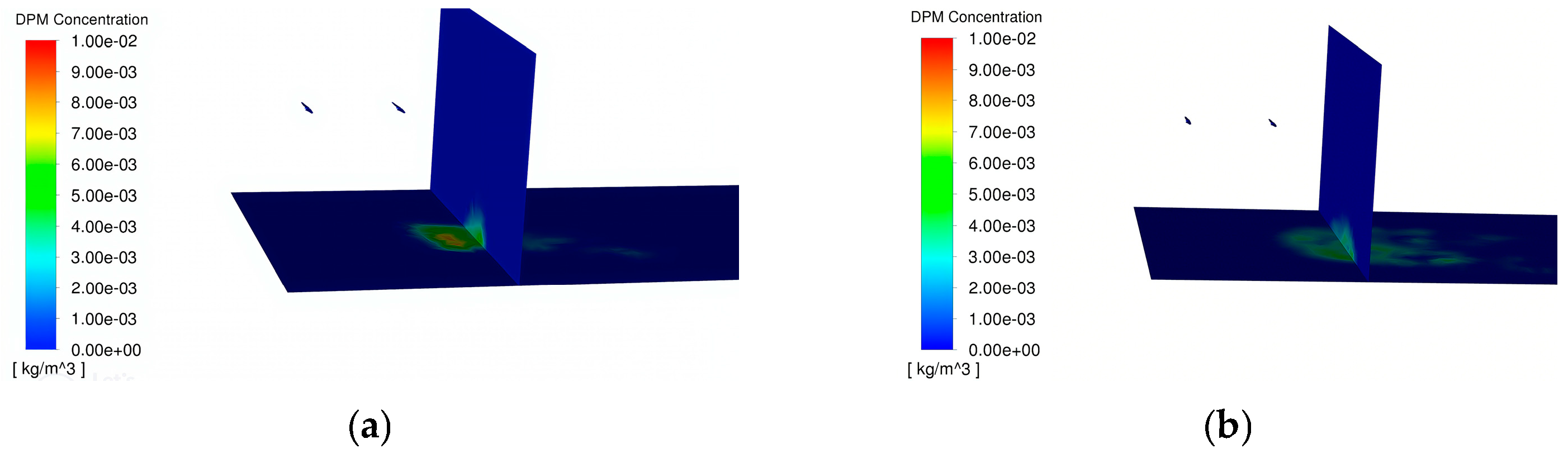

2.2.1. Droplet Drift Simulation Under a Coupled Wind Field

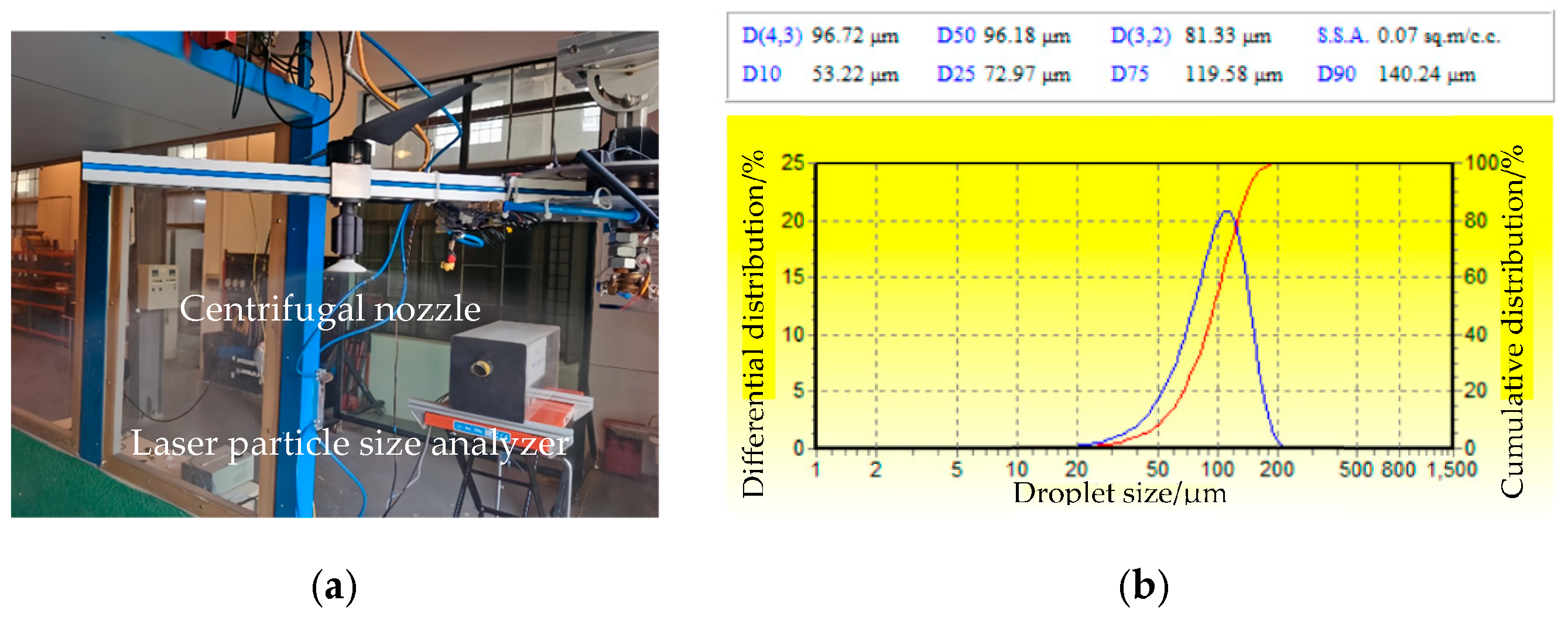

2.2.2. Wind Tunnel Test for Droplet Drift Performance Under a Coupled Wind Field

2.3. Construction of Droplet Drift Model for a Centrifugal Nozzle

2.3.1. Influence of UAV Operation Parameters on Droplet Drift Characteristics

2.3.2. Numerical Simulation of Droplet Drift for Centrifugal Nozzles Under Different Operating Parameters

2.3.3. Droplet Drift Prediction Model for Agricultural UAVs

3. Results

3.1. Rotor Wind Field Intensity

3.2. Droplet Drift Performance Under Coupled Wind Field

3.2.1. Characteristics of Coupled Wind Field

3.2.2. The Atomization and Drift Characteristics of Flat-Fan Nozzles

3.3. Droplet Drift Model for Centrifugal Nozzles

3.3.1. Analysis of Single-Factor Influence

3.3.2. Results of Orthogonal Experiment and Factor Significance

3.3.3. Droplet Drift Prediction Model and Verification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lan, Y.; Chen, S. Current status and trends of plant protection UAV and its spraying technology in China. Int. J. Precis. Agric. Aviat. 2018, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, R.; Yang, J.; Chen, L. Development status and key technologies of plant protection UAVs in China: A review. Drones 2022, 6, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.J.; Yuan, X.; Kim, M.; Kyung, K.; Noh, H. Monitoring and risk analysis of residual pesticides drifted by unmanned aerial spraying. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, W.; Du, C.; Ze, Y.; Ni, X.; Wang, S. Research on the prediction model and its influencing factors of droplet deposition area in the wind tunnel environment based on UAV spraying. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsari, P.; Gil, E.; Marucco, P.; Zande, J.; Nuyttens, D.; Herbst, A.; Gallart, M. Field-crop-sprayer potential drift measured using test bench: Effects of boom height and nozzle type. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 154, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, X.; Zeng, A.; Andreas, H.; Supakorn, W. Measuring method and experiment on spray drift of chemicals applied by UAV sprayer based on an artificial orchard test bench. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. (Trans. CSAE) 2020, 36, 56–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Andreas, H.; Jane, B.; Zeng, A.; Zhao, C.; He, X. Stereoscopic test method for low-altitude and low-volume spraying deposition and drift distribution of plant protection UAV. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. (Trans. CSAE) 2020, 36, 54–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, G.; Lan, Y. Drift Evaluation of a Quadrotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Sprayer: Effect of Liquid Pressure and Wind Speed on Drift Potential Based on Wind Tunnel Test. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Han, S.; Yang, F. Research on downwash flow and droplet distribution of four-rotor plant protection UAV coupling with wind field. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2024, 45, 81–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Hou, C.; He, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, S. CFD simulation and experimental verification of the spatial and temporal distributions of the downwash airflow of a quad-rotor agricultural UAV in hover. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 172, 105343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, X.; He, Y.; Huang, H.; Luo, S. CFD simulation and measurement of the downwash airflow of a quadrotor plant protection UAV during operation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 201, 107286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Hou, C.; Fang, M.; Chen, X. Numerical Simulation of the Effects of Downwash Airflow and Crosswinds on the Spray Performance of Quad-Rotor Agricultural UAVs. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Wen, S.; Zhang, J.; Lan, Y.; Huang, G. Analysis of the two-way fluid-structure interaction between the rice canopy and the downwash airflow of a quadcopter UAV. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 250, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y. Dynamic simulation of fluid-structure interactions between leaves and airflow during air-assisted spraying: A case study of cotton. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Liu, Z.; Qin, Y.; Long, B.; Li, H.; Li, J. Airflow characteristics of rotorcraft plant protection UAV operating in rice fields. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 226, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J. Pesticide/Disinfectant Dispersion Modeling in Aerial Spraying. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teske, M.E.; Thistle, H.W.; Londergan, R.J. Modification of droplet evaporation in the simulation of fine droplet motion using AGDISP. Trans. ASABE 2011, 54, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teske, M.E.; Thistle, H.W.; Fritz, B.K. Modeling aerially applied sprays: An update to AGDISP model development. Trans. ASABE 2019, 62, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teske, M.E.; Wachspress, D.A.; Thistle, H.W. Prediction of aerial spray release from UAVs. Trans. ASABE 2018, 61, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tang, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, R.; Xu, M. Numerical simulation of spray drift and deposition from a crop spraying aircraft using a CFD approach. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 166, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Chen, L.; Deng, W.; Hewitt, A. Numerical simulation of the downwash flow field and droplet movement from an unmanned helicopter for crop spraying. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Wen, Y.; Tang, Q.; Wang, W. Design and application of a monitoring system for spray deposition and drift by plant protection unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). J. Plant Prot. 2021, 48, 537–545. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C. Design and Research a Monitoring System and Droplet Drift Model of Helicopter for Agriculture Aerial Spraying Application. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Research progress and prospects of spraying of multi-rotor plant protection UAV. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensis 2024, 46, 1341–1355. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/36.1028.S.20240902.1509.002.html (accessed on 30 December 2025). (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Arash, D.; Rasoul, A.; Ehsan, R. Experimental and numerical investigation on the spraying performance of an agricultural unmanned aerial vehicle. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 11, 110083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Chen, P. Analysis of the research progress on the deposition and drift of spray droplets by plant protection UAVs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, M.; Newton, S.; Knowles, J.; Garmory, A. The influence of rotor downwash on spray distribution under a quadrotor unmanned aerial system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y. CFD analysis and RBFNN-based optimization of spraying system for a six-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) sprayer. Crop Prot. 2023, 174, 106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Xue, X.; Cai, C.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Q. Numerical Simulation and Analysis on Spray Drift Movement of Multirotor Plant Protection Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Energies 2018, 11, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, G.; Donald, J.B.; Bihara, S. Computational fluid dynamics analysis of an agricultural spray in a crossflow. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 11, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22866; Equipment for Crop Protection-Methods for Field Measurement of Spray Drift Wind tunnels. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Torrent, X.; Garcerá, C.; Moltó, E.; Chueca, P.; Abad, R.; Grafulla, C.; Román, C.; Planas, S. Comparison between standard and drift reducing nozzles for pesticide application in citrus: Part I. Effects on wind tunnel and field spray drift. Crop Prot. 2017, 96, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuyttens, D.; Taylor, W.A.; De Schampheleire, M.; Verboven, P.; Dekeyser, D. Influence of nozzle type and size on drift potential by means of different wind tunnel evaluation methods. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 103, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Xue, X.; Cai, C.; Wang, B. Performance evaluation of UAVs in wheat disease control. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Xue, X.; Qin, W.; Cai, C.; Zhou, L. Optimization and test for structural parameters of UAV spraying rotary cup atomizer. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, H. CFD simulation of pesticide spray from air-assisted sprayers in an apple orchard: Tree deposition and off-target losses. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 175, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Xue, X.; Lan, Y. Numerical simulation and verification of rotor downwash flow field of plant protection UAV at different rotor speeds. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1087636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Xue, X.; Yang, F. Trajectory and deposition distribution features of centrifugal atomization nozzle droplet. J. Jiangsu Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 38, 18–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahiyoon, S.A.; Ren, Z.; Wei, P.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Yan, X.; Yuan, H. Recent development trends in plant protection UAVs: A journey from conventional practices to cutting-edge technologies—A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2024, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputti, T.; de Oliveira, L.P.; Rodrigues, C.; Cremonez, P.; Foshee, W.; Simmons, A.M.; Silva, A.L. Flight Parameters for Spray Deposition Efficiency of Unmanned Aerial Application Systems (UAASs). Drones 2025, 9, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Oouyang, F.; Wang, G.; Huang, X.; Deng, X.; Cheng, S. Effect of droplet size parameters on droplet deposition and drift of aerial spraying by using plant protection UAV. Agronomy 2020, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Flight Height (m) | Rotor Wind Speed (m/s) | Flight Speed (m/s) | DV50 (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | |||||

| 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 3 | 100 | |

| 2 | 2 | 15 | 5 | 200 | |

| 3 | 2.5 | 20 | 7 | 300 | |

| Factor | Flight Height (m) | Rotor Wind Speed (m/s) | Flight Speed (m/s) | DV50 (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | |||||

| 1 | 24.43 ± 1.34 (b) | 46.28 ± 1.66 (a) | 19.07 ± 0.72 (c) | 30.20 ± 1.74 (a) | |

| 2 | 27.39 ± 1.07 (b) | 27.39 ± 1.07 (b) | 27.39 ± 1.07 (b) | 27.39 ± 1.07 (a) | |

| 3 | 65.94 ± 2.35 (a) | 13.48 ± 0.54 (c) | 33.94 ± 0.61 (a) | 29.98 ± 0.84 (a) | |

| Experiment No. | Flight Height (m) | Rotor Wind Speed (m/s) | Flight Speed (m/s) | Drift Rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat 1 | Repeat 2 | Repeat 3 | ||||

| 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 3 | 33.23 | 32.59 | 29.32 |

| 2 | 1.5 | 15 | 5 | 23.61 | 23.72 | 25.98 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 20 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 45.44 | 44.36 | 43.71 |

| 5 | 2 | 15 | 7 | 30.14 | 36.23 | 33.93 |

| 6 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 3.02 | 3.38 | 3.35 |

| 7 | 2.5 | 10 | 7 | 82.97 | 86.98 | 86.80 |

| 8 | 2.5 | 15 | 3 | 37.13 | 38.31 | 36.39 |

| 9 | 2.5 | 20 | 5 | 14.21 | 14.62 | 14.48 |

| Source of Variance | Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F-Value | Pr > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight height | 2 | 3453.5 | 1726.75 | 45.71 | <0.0001 |

| Rotor wind speed | 2 | 10,404.29 | 5202.15 | 137.72 | <0.0001 |

| Flight speed | 2 | 1194.17 | 597.08 | 15.81 | <0.0001 |

| Error | 20 | 755.45 | 37.77 |

| Variable | Estimated Value | t Value | Pr > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flight height | 38.641 | 13.01 | <0.0001 |

| Rotor wind speed | 2.514 | 1.56 | 0.1242 |

| Flight speed | −13.473 | −2.82 | 0.0069 |

| Flight height * Rotor wind speed | −3.177 | −4.36 | <0.0001 |

| Flight height * Flight speed | 7.909 | 3.56 | 0.0008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Huang, M.; Cai, C.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, Y.; Xue, X. Construction of a CFD Simulation and Prediction Model for Pesticide Droplet Drift in Agricultural UAV Spraying. Agronomy 2026, 16, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010129

Zhou Q, Zhang S, Huang M, Cai C, Zhang H, Jiao Y, Xue X. Construction of a CFD Simulation and Prediction Model for Pesticide Droplet Drift in Agricultural UAV Spraying. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Qingqing, Songchao Zhang, Meng Huang, Chen Cai, Haidong Zhang, Yuxuan Jiao, and Xinyu Xue. 2026. "Construction of a CFD Simulation and Prediction Model for Pesticide Droplet Drift in Agricultural UAV Spraying" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010129

APA StyleZhou, Q., Zhang, S., Huang, M., Cai, C., Zhang, H., Jiao, Y., & Xue, X. (2026). Construction of a CFD Simulation and Prediction Model for Pesticide Droplet Drift in Agricultural UAV Spraying. Agronomy, 16(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010129