Visualization Techniques for Spray Monitoring in Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Physical Basis of Droplet and Rotor-Induced Flow Field

2.1. Droplet Formation and Initial Characteristics

2.1.1. Nozzle Types and Initial Droplet Generation Mechanisms

2.1.2. Dynamics of Liquid Sheet Breakup and Mechanisms of Drop Size Distribution Formation

2.1.3. Initial Droplet Velocity, Velocity Fluctuations, and Standardized Measurement Framework

2.2. Droplet Motion and Evolution in Rotor Flow

2.2.1. Fundamental Mechanisms of Rotor-Induced Flow on Droplet Transport

2.2.2. Droplet Dynamics in UASS Downwash and Multiscale Drift Responses

2.3. Droplet–Flow Coupling and Visualization Requirements

2.3.1. Multiscale Coupling Mechanisms Between Droplet Initial Conditions and Rotor-Induced Flow

2.3.2. Necessity of Visualization-Based Monitoring

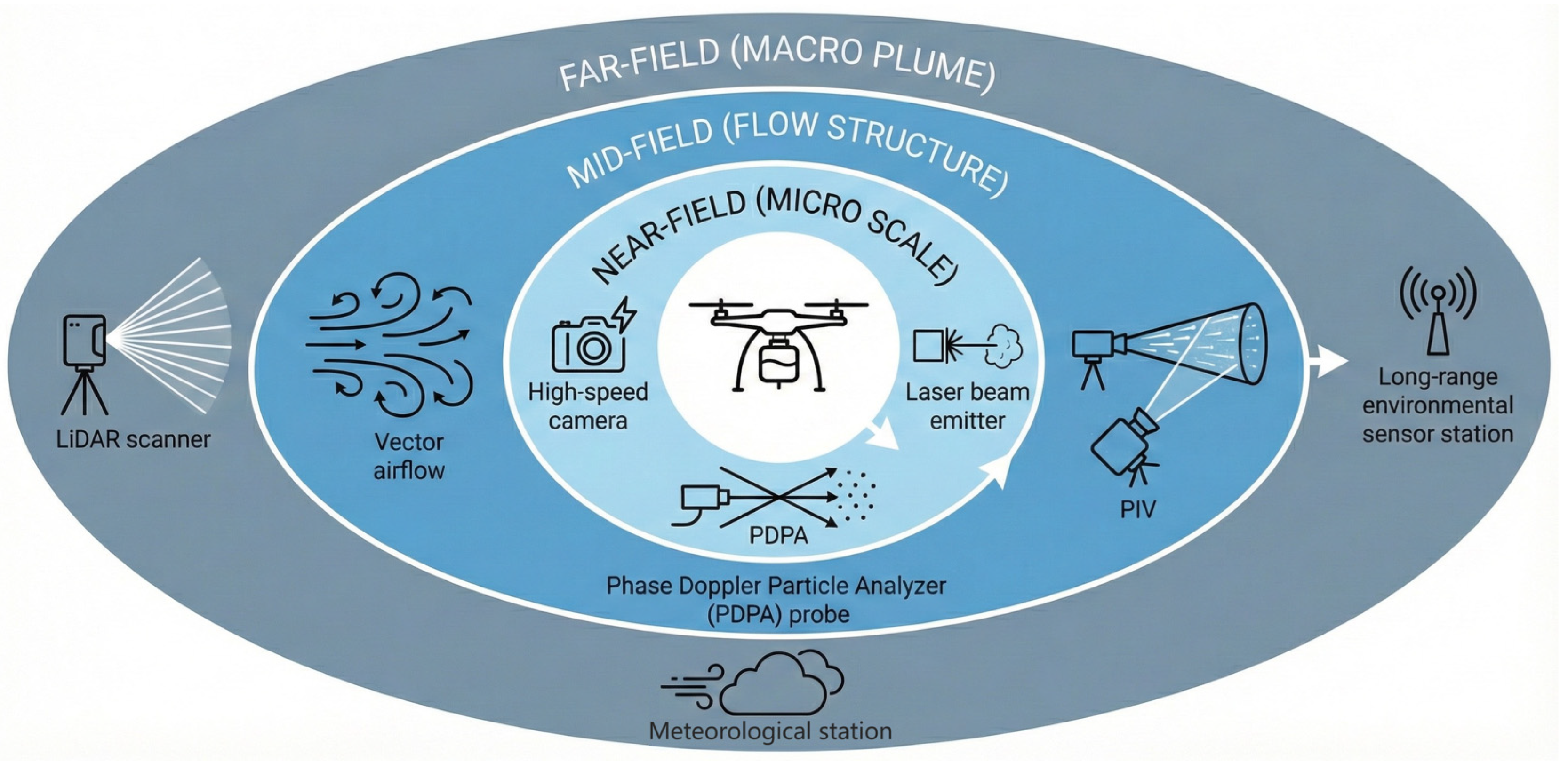

3. Visualization Monitoring Technology Framework for Spray Processes

3.1. Optical Imaging Visualization Techniques

3.1.1. Scattering-Based Techniques

3.1.2. Direct Imaging Techniques

3.1.3. Holographic Interferometry Methods (Wavefront Reconstruction Techniques)

3.2. Laser Scattering and Volume Reconstruction Technologies

3.2.1. Laser Diffraction Systems

3.2.2. Laser Imaging and Light-Sheet Techniques

3.2.3. LiDAR and Three-Dimensional Reconstruction

3.3. Standardization Challenges in Multisource, Flow–Spray Fusion Visualization and Measurement

4. UASS Spray Visualization Practice and Applications

4.1. Experimental Platform Validation: From Wind Tunnels to Controlled Environments

4.2. Field-Scale Visualization: From Plume Structure to Target Deposition

4.3. Visualization and Equivalent Analysis of Rotor–Canopy Vortex Structures

4.4. Model Integration and Application Expansion: From Visual Understanding to Computable Rules

5. Intelligent Processing and Analysis of Visualization Data

5.1. Image-Level Recognition of Droplet and Flow-Field Features

5.2. Multimodal Feature Fusion and Associative Modeling

5.3. Intelligent Prediction and Spray Parameter Optimization

6. Conclusions and Prospects

- (1)

- Multiscale model cross-validation and standardization based on a unified feature system

- (2)

- Wind–spray–target coupled modeling oriented toward vortex–canopy interactions

- (3)

- Intelligent closed-loop control driven by embedded multimodal sensing

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anken, T.; Coupy, G.; Dubuis, P.H.; Favre, G.; Geiser, H.C.; Gurba, A.; Häni, M.; Hochstrasser, M.; Landis, M.; Maitre, T. Plant protection treatments in Switzerland using unmanned aerial vehicles: Regulatory framework and lessons learned. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, X.; Li, W.; Yan, K.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pawlowski, L.; Lan, Y. Progress in agricultural unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) applied in China and prospects for Poland. Agriculture 2022, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, P.K.; Freeland, R.S. Politics & technology: US polices restricting unmanned aerial systems in agriculture. Food Policy 2014, 49, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezić, A.; Trudić, B.; Stamenković, Z.; Kuzmanović, B.; Perić, S.; Ivošević, B.; Buđen, M.; Petrović, K. Drone-related agrotechnologies for precise plant protection in western balkans: Applications, possibilities, and legal framework limitations. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahiyoon, S.A.; Ren, Z.; Wei, P.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Yan, X.; Yuan, H. Recent development trends in plant protection UAVs: A journey from conventional practices to cutting-edge technologies—A comprehensive review. Drones 2024, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y. Optimization of Rotor Layout and Energy Consumption Test of Multi-Wing Single-Arm Structure Electric UAV. Master’s Thesis, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, M.N.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wenjiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Naqvi, S.M.Z.A. Application of unmanned aerial vehicles in precision agriculture. In Precision Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Z. Research on Vector Anti-Drift System for Plant Protection Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y. Precision Agricultural Aviation Application Technology; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; ISBN 3031899172. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, M.; Xiao, S.; Yu, T.; He, Y. Influence of UAV flight speed on droplet deposition characteristics with the application of infrared thermal imaging. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, B.K.; Hoffmann, W.C.; Bagley, W.E.; Kruger, G.R.; Czaczyk, Z.; Henry, R.S. Measuring droplet size of agricultural spray nozzles− measurement distance and airspeed effects. At. Spray 2014, 24, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Han, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gu, W.; Jin, Y.; Xue, X.; Lan, Y. Path planning optimization with multiple pesticide and power loading bases using several unmanned aerial systems on segmented agricultural fields. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 53, 1882–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16122-5:2020; Agricultural and Forestry Machines—Inspection of Sprayers in use—Part 5: Aerial Spray Systems. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 5682-1:2017; Equipment for Crop Protection—Spraying Equipment—Part 1: Test Methods for Sprayer Nozzles. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 24253-1:2015; Crop Protection Equipment—Spray Deposition Test for Field Crop—Part 1: Measurement in a Horizontal Plane. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Saleem, S.R.; Zaman, Q.U.; Schumann, A.W.; Naqvi, S.M.Z.A. Variable rate technologies: Development, adaptation, and opportunities in agriculture. In Precision Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, J.T.; Shrimpton, J.S.; Whybrew, A. A digital image analysis technique for quantitative characterisation of high-speed sprays. Opt. Laser Eng. 2007, 45, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavali, P.; Kalashetty, S. Experimental Analysis of Droplet Characterisation of Centrifugal-Assisted Sprayer. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. C 2023, 104, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, S.; Yubin, L.; Hoffmann, C.; Chunjiang, Z.; Liping, C.; Xingxing, L.; Yu, T. A novel detection method of spray droplet distribution based on LIDARs. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wen, S.; Zhang, L.; Lan, Y.; Chen, X. Extraction of crop canopy features and decision-making for variable spraying based on unmanned aerial vehicle LiDAR data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, M.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Wang, S. Numerical verification on influence of multi-feature parameters to the downwash airflow field and operation effect of a six-rotor agricultural UAV in flight. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190, 106425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, P.; Ma, G.; Wu, J.; Liao, J.; Ma, H.; Qiu, J.; Qin, Y. Time series model for predicting the disturbance of lychee canopy by wind field in unmanned aerial spraying system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Xue, X.; Lan, Y. Numerical simulation and verification of rotor downwash flow field of plant protection UAV at different rotor speeds. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1087636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, L.; Wen, Y.; Tang, Q.; Li, L. Key technologies for testing and analyzing aerial spray deposition and drift: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Precis. Agric. Aviat. 2020, 3, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, G.; Ashtiani-Araghi, A.; Tekin, A.B.; Lee, C. Laboratory Methods for the Measurement of Spray Characteristics of the Nozzles in UAV Sprayers: A Review. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 50, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar-irimie, A.; Ranta, O.; STĂNILĂ, S.; Marian, O. Study Regarding Methods and Techniques Used for Analysis of Spray Drift and Droplet Size Distribution by Agricultural Spraying Machines. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca. Agric. 2025, 82, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Chen, P.; Xu, W.; Chen, S.; Han, Y.; Lan, Y.; Wang, G. Influence of the downwash airflow distribution characteristics of a plant protection UAV on spray deposit distribution. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 216, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhnenko, I.; Alonzi, E.R.; Fredericks, S.A.; Colby, C.M.; Dutcher, C.S. A review of liquid sheet breakup: Perspectives from agricultural sprays. J. Aerosol Sci. 2021, 157, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackiw, I.M.; Ashgriz, N. On aerodynamic droplet breakup. J. Fluid Mech. 2021, 913, A33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, T.; Song, C.; Yu, X.; Shan, C.; Gu, H.; Lan, Y. Evaluation of spray drift of plant protection drone nozzles based on wind tunnel test. Agriculture 2023, 13, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, V.; Radočaj, D.; Jurišić, M. Machine Learning Methods for Evaluation of Technical Factors of Spraying in Permanent Plantations. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruto, E.; Manetto, G.; Papa, R.; Longo, D. Modelling spray pressure effects on droplet size distribution from agricultural nozzles. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira Martins, R.; Freitas, M.A.M.D.; Lima, A.D.C.; Furtado Junior, M.R. Effect of nozzle type and pressure on spray droplet characteristics. Idesia 2021, 39, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, G.J.; Hewitt, A.J.; Adkins, S.W.; Hanan, J.; Zhang, H.; Noller, B. A comparison of initial spray characteristics produced by agricultural nozzles. Crop Prot. 2013, 53, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Kim, Y.; Jun, H.; Choi, I.S.; Woo, J.; Kim, Y.; Yun, Y.; Choi, Y.; Alidoost, R.; Lee, J. Evaluation of Spray Characteristics of Pesticide Injection System in Agricultural Drones. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 45, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, E.P.; Guerreiro, J.C.; Ferreira-Filho, P.J.; Do Nascimento, V.; Ferrari, S.; Galindo, F.S.; Funichello, M.; Raetano, C.G.; Pagliari, P.H.; Chechetto, R.G. Performance of spray nozzles and droplet size on glufosinate deposition and weed biological efficacy. Crop Prot. 2024, 177, 106560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canu, R.; Puggelli, S.; Essadki, M.; Duret, B.; Menard, T.; Massot, M.; Reveillon, J.; Demoulin, F.X. Where does the droplet size distribution come from? Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2018, 107, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidoost Dafsari, R.; Yu, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, J. Effect of geometrical parameters of air-induction nozzles on droplet characteristics and behaviour. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 209, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryer, S.; Raymond, J. Interpreting Image Patterns for Agricultural Sprays Using Statistics and Machine Learning Techniques. Fluids 2024, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 25358:2018; Crop Protection Equipment—Droplet-Size Spectra from Atomizers—Measurement and Classification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Calderone, G.; Catania, P.; Comparetti, A.; Ferro, M.V.; Greco, C.; Vallone, M.; Orlando, S. Spray deposition efficiency of unmanned aerial spraying systems in hillside vineyards with variable slope. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Douzals, J.P.; Lan, Y.; Cotteux, E.; Delpuech, X.; Pouxviel, G.; Zhan, Y. Characteristics of unmanned aerial spraying systems and related spray drift: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 870956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dorr, G.J.; Khashehchi, M.; He, X. Performance of selected agricultural spray nozzles using particle image velocimetry. J. Agric. Sci. Tech. 2015, 17, 601–613. [Google Scholar]

- Ansaripour, M.; Dafsari, R.A.; Yu, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, J. Characteristics of a tip-vortex generated by a single rotor used in agricultural spraying drone. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2023, 149, 110995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, J.; Yao, W.; Zhan, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y. Distribution characteristics on droplet deposition of wind field vortex formed by multi-rotor UAV. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e220024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombes, M.; Newton, S.; Knowles, J.; Garmory, A. The influence of rotor downwash on spray distribution under a quadrotor unmanned aerial system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, A.J. Spray drift: Impact of requirements to protect the environment. Crop Prot. 2000, 19, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, B.K.; Hoffmann, W.C. Measuring Spray Droplet Size from Agricultural Nozzles Using Laser Diffraction. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 115, 54533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Guo, J.; Guan, R.; Zhou, Z.; Lan, Y.; Chen, S. Movement Characteristics of Droplet Deposition in Flat Spray Nozzle for Agricultural UAVs. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Herbst, A.; Zeng, A.; Wongsuk, S.; Qiao, B.; Qi, P.; Bonds, J.; Overbeck, V.; Yang, Y.; Gao, W.; et al. Assessment of spray deposition, drift and mass balance from unmanned aerial vehicle sprayer using an artificial vineyard. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpuech, X.; Pouxviel, G.; Cotteux, E.; Verges, A.; Douzals, J. Evaluation of aerial drift during drone spraying of an artificial vineyard. Ives Tech. Rev. Vine Wine 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Han, J.; Ning, Z.; Lan, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhang, J.; Ge, Y. Numerical analysis and validation of spray distributions disturbed by quad-rotor drone wake at different flight speeds. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 166, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, S.; Manetto, G.; Pascuzzi, S.; Pessina, D.; Cerruto, E. Drop Size Measurement Techniques for Agricultural Sprays:A State-of-The-Art Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qi, P.; Li, Y.; He, X. Visualization of Aerial Droplet Distribution for Unmanned Aerial Spray Systems Based on Laser Imaging. Drones 2024, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S.; Hogan, C.J.; Fredericks, S.A.; Hong, J. Visualization and characterization of agricultural sprays using machine learning based digital inline holography. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachalo, W.D. Method for measuring the size and velocity of spheres by dual-beam light-scatter interferometry. Appl. Opt. 1980, 19, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuyttens, D.; De Schampheleire, M.; Steurbaut, W.; Baetens, K.; Verboven, P.; Nicolai, B.; Ramon, H.; Sonck, B. Characterization of agricultural sprays using laser techniques. Asp. Appl. Biol. 2006, 77, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Lodwik, D.; Pietrzyk, J.; Malesa, W. Analysis of volume distribution and evaluation of the spraying spectrum in terms of spraying quality. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, H.; Damaschke, N.; Borys, M.; Tropea, C. Laser Doppler and Phase Doppler Measurement Techniques; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 3662051656. [Google Scholar]

- Melling, A. Tracer particles and seeding for particle image velocimetry. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1997, 8, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropea, C. Optical particle characterization in flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2011, 43, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fansler, T.D.; Parrish, S.E. Spray measurement technology: A review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 26, 12002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghe, A.; Cossali, G.E. Quantitative optical techniques for dense sprays investigation: A survey. Opt. Laser Eng. 2012, 50, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, R.J.; Westerweel, J. Particle Image Velocimetry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, M.; Willert, C.E.; Scarano, F.; Kähler, C.J.; Wereley, S.T.; Kompenhans, J. Particle Image Velocimetry: A Practical Guide; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Cock, N.; Massinon, M.; Nuyttens, D.; Dekeyser, D.; Lebeau, F. Measurements of reference ISO nozzles by high-speed imaging. Crop Prot. 2016, 89, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Lin, W.; Wu, Y.; Wu, X. Spray trajectory and 3D droplets distribution of liquid jet in crossflow with digital inline holography. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2022, 139, 110725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Lin, W.; Song, G.; He, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Cen, K. Picosecond pulsed digital off-axis holography for near-nozzle droplet size and 3D distribution measurement of a swirl kerosene spray. Fuel 2021, 283, 119124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trolinger, J.D.; Mansoor, M.M. History and metrology applications of a game-changing technology: Digital holography. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2022, 39, A29–A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Meng, H. Digital holography of particle fields: Reconstruction by use of complex amplitude. Appl. Optics 2003, 42, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, V.D.S.; Nuyttens, D.; Langenakens, J.; Pereira, J.V.; Da Silva, R.P. Smartphone image-based framework for quick, non-invasive measurement of spray characteristics. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Burgers, T.; Nguyen, K. AI-enabled droplet detection and tracking for agricultural spraying systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiti, M.; Garcia, S.; Lempereur, C.; Doublet, P.; Kristensson, E.; Berrocal, E. Droplet sizing in atomizing sprays using polarization ratio with structured laser illumination planar imaging. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 4065–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.; Llorens, J.; Llop, J.; Fàbregas, X.; Gallart, M. Use of a Terrestrial LIDAR Sensor for Drift Detection in Vineyard Spraying. Sensors 2013, 13, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Müller, J.; He, X. Visualization of Lidar-Based 3D Droplet Distribution Detection for Air-Assisted Spraying. Agriengineering 2023, 5, 1136–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, S.; Cerruto, E.; Manetto, G.; Lupica, S.; Nuyttens, D.; Dekeyser, D.; Zwertvaegher, I.; Furtado Júnior, M.R.; Vargas, B.C. Comparison between Liquid Immersion, Laser Diffraction, PDPA, and Shadowgraphy in Assessing Droplet Size from Agricultural Nozzles. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijs, R.; Kooij, S.; Holterman, H.J.; van de Zande, J.; Bonn, D. Drop size measurement techniques for sprays: Comparison of image analysis, phase Doppler particle analysis, and laser diffraction. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 15315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, L.; Hewitt, A.J.; He, X.; Ding, C.; Tang, Q.; Liu, B. Toward a remote sensing method based on commercial LiDAR sensors for the measurement of spray drift and potential drift reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, M.; Johnson, B.; Leishman, J.G. Turbulent tip vortex measurements using dual-plane stereoscopic particle image velocimetry. AIAA J. 2009, 47, 1826–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, L.; Wan, J.; Musiu, E.M.; Zhou, J.; Lu, Z.; Wang, P. Numerical simulation of downwash airflow distribution inside tree canopies of an apple orchard from a multirotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) sprayer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 195, 106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.D.; Mortimer, V.; Lydon, M. Droplet sizing and imaging of agricultural sprays using particle/droplet image analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pesticide Application for Drift Management, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 27–29 October 2004; WSU: Pullman, WA, USA, 2004; pp. 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 22856: 2008; Equipment for Crop Protection—Methods for the Laboratory Measurement of Spray Drift—Wind Tunnels. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- GB/T 32241-2015; Standardization Administration of China: Methods for Testing Spray Drift of Pesticide Application. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Wang, Z.; He, X.; Li, T.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Deng, X.J. Evaluation method of pesticide droplet drift based on laser imaging. Trans. Csae 2019, 35, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, G.; Lan, Y. Drift Evaluation of a Quadrotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Sprayer: Effect of Liquid Pressure and Wind Speed on Drift Potential Based on Wind Tunnel Test. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Cui, L.; Yan, X.; Han, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhan, Y.; Wu, J.; Qin, Y.; Chen, P.; Lan, Y. Field Evaluation of Different Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems Applied to Control Panonychus citri in Mountainous Citrus Orchards. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Hou, Q.; Chen, L.; Yong, R.; Ma, J.; Yang, D.; Yuan, H. Optimizing UAV spray parameters to improve precise control of tobacco pests at different growth stages. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 5809–5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lan, Y.; Qi, H.; Chen, P.; Hewitt, A.; Han, Y. Field evaluation of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) sprayer: Effect of spray volume on deposition and the control of pests and disease in wheat. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindel, T.J. X-ray imaging techniques to quantify spray characteristics in the near field. At. Spray 2018, 28, 1029–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Hung, D.; Xu, M. Dense-field spray droplet size quantification of flashing boiling atomization using structured laser illumination planar imaging technique. Fuel 2023, 335, 127085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wen, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, Q.; Xu, T.; Chen, S.; Lan, Y. Downwash airflow field distribution characteristics and their effect on the spray field distribution of the DJI T30 six-rotor plant protection UAV. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2023, 16, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shan, C.; Zhang, H.; Song, C.; Lan, Y. Evaluation of liquid atomization and spray drift reduction of hydraulic nozzles with four spray adjuvant solutions. Agriculture 2023, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, X.; Gregorio, E.; Rosell-Polo, J.R.; Arnó, J.; Peris, M.; van de Zande, J.C.; Planas, S. Determination of spray drift and buffer zones in 3D crops using the ISO standard and new LiDAR methodologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasbi, M.K.; Dafsari, R.A.; Charanandeh, A.; Yu, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, J. Parametric study on the internal geometry affecting agricultural air induction nozzle performance. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 023316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22866:2005; Equipment for crop protection—Methods for Field Measurement of Spray Drift. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Tang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Chen, L.; Deng, W.; Xu, M.; Xu, G.; Li, L.; Hewitt, A. Numerical simulation of the downwash flow field and droplet movement from an unmanned helicopter for crop spraying. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzi, G.; Becce, L.; Ali, A.; Bortolini, M.; Gregoris, E.; Feltracco, M.; Barbaro, E.; Gronauer, A.; Gambaro, A.; Mazzetto, F. Methodological Advancements in Testing Agricultural Nozzles and Handling of Drop Size Distribution Data. Agriengineering 2025, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minov, S.; Cointault, F.; Vangeyte, J.; Pieters, J.; Nuyttens, D. Spray Droplet Characterization from a Single Nozzle by High Speed Image Analysis Using an In-Focus Droplet Criterion. Sensors 2016, 16, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.; Nguyen, K. Real-Time Droplet Detection for Agricultural Spraying Systems: A Deep Learning Approach. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Jianzhou, G.; Shiyun, H.; Zhiyan, Z.; Yubin, L. Detection and tracking of agricultural spray droplets using GSConv-enhanced YOLOv5s and DeepSORT. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Jat, D.; Sahni, R.K.; Jyoti, B.; Kumar, M.; Subeesh, A.; Parmar, B.S.; Mehta, C.R. Measurement of droplets characteristics of UAV based spraying system using imaging techniques and prediction by GWO-ANN model. Measurement 2024, 234, 114759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.; Gallart, M.; Balsari, P.; Marucco, P.; Almajano, M.P.; Llop, J. Influence of wind velocity and wind direction on measurements of spray drift potential of boom sprayers using drift test bench. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 202, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cryer, S.; Acharya, L.; Raymond, J. Video and image classification using atomisation spray image patterns and deep learning. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 200, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, C.R.; Ellis, M.B.; Miller, P. Techniques for measurement of droplet size and velocity distributions in agricultural sprays. Crop Prot. 1997, 16, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cryer, S.; Raymond, J.; Acharya, L. Interpreting atomization of agricultural spray image patterns using latent Dirichlet allocation techniques. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2020, 4, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subcategory | Representative Techniques | Measurement Dimension | Key Retrieved Information | Major Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scattering-based diagnostics | PDPA, LDA/LDV | Point-wise | Droplet size distribution (Dv0.1, Dv0.5, Dv0.9), velocity, RSF | High accuracy and repeatability; standardized reference for nozzle atomization and calibration | High cost; limited sampling volume; sensitive to alignment and droplet concentration; bias for non-spherical or air-entrained droplets |

| Direct imaging techniques | PDIA, high-speed imaging/shadowgraphy, PIV | Planar (2D) | Droplet size, morphology, spray angle, breakup dynamics, velocity fields | Intuitive visualization; flexible deployment; capable of resolving non-spherical droplets and flow–spray interactions | Strict requirements on focus and depth of field; reduced reliability in dense sprays; intensive post-processing |

| holographic interferometry methods | DIH, DHM, DHPIV | Volumetric (3D full-field) | Three-dimensional droplet size, spatial position, velocity, and dynamic evolution | Large depth of field; single-shot 3D reconstruction; suitable for dense and complex spray fields | High system complexity; heavy computational burden; stringent stability and calibration requirements |

| Subcategory | Representative Techniques | Spatial Scale | Key Retrieved Information | Major Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDS | Laser diffraction analyzers | Local/statistical | Volumetric droplet size distribution (Dv metrics) | High degree of standardization; rapid measurement; large statistical sample size | Systematic bias for non-spherical or air-filled droplets; overestimation of fine droplets at low airspeeds |

| Laser imaging and light-sheet techniques | Scattered-light imaging, line-laser scanning, 3p-SLIPI | Planar to quasi-3D | Drift index (DIX), plume height, drift distance, surface-area mean diameter (D21) | High sensitivity to drift behavior; strong correlation with field deposition measurements | Susceptible to ambient light and background aerosols; requires cross-calibration |

| LiDAR and three-dimensional reconstruction | Scanning LiDAR, multi-line laser scanners, line-laser–camera systems | Large-scale 3D | Three-dimensional point cloud density, plume geometry, drift potential indices | Large measurement range; real-time, non-intrusive plume monitoring; well suited for UASS field studies | High equipment cost; limited sensitivity to very fine droplets; complex point-cloud interpretation |

| Technology Category | Measurement Principle and Key Indicators | Typical Application Scenarios | Advantages and Representative Results | Limitations and Improvement Directions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDPA | Laser beam crossing area; calculates droplet size and velocity from phase difference in scattered signal, simultaneous acquisition of droplet size spectrum and velocity spectrum. | Near-field of nozzle, climate chambers, wind tunnels | High accuracy, good reproducibility; standard method for nozzle atomization and reference nozzle calibration [57]. | Expensive equipment, sensitive to alignment and particle concentration, limited measurement volume; bias in measuring gas-phase, non-spherical droplets. |

| PDIA | Uses pulse light source and high-speed imaging to segment and count droplet images, directly identifying droplet size and number density. | Laboratories, wind tunnels, near-field and outer field near nozzle | Flexible operation, moderate cost; can identify non-spherical and gas-containing droplets; results consistent with PDPA in the mid-size range [81]. | High requirements for focus and depth of field management; small droplets are susceptible to noise interference; for high-concentration spray fields, threshold and focus criteria need to be combined. |

| HSI/Shadowgraphy | Continuous frame capture of liquid film breakage and droplet formation process, extracting breakage time, liquid bridge evolution, spray angle, etc. | Atomization mechanism research, centrifugal nozzle performance analysis | Intuitive display of liquid film rupture, aggregation, and reatomization processes; supports breakage model validation [66]. | Sensitive to lighting, background, and focus conditions; high post-processing workload; precise calibration needed for droplet size quantification. |

| DIH | Records holograms of droplet clusters and reconstructs different depth planes to obtain 3D droplet size and location distribution. | High-concentration spray fields, complex droplet cluster structures, UASS local 3D measurements | Large depth of field, complete volume information; combined with deep learning, high precision measurements in the range of 20–500 μm, overcoming LD settling bias [55]. | Large computational requirements for reconstruction, high demands on system stability and calibration; large-scale application requires calculation acceleration. |

| LD | Based on Mie scattering, measures scattering angle intensity distribution and inverts volume distribution. | Nozzle laboratory benchmark testing | Highly standardized, fast measurement speed, large statistics; commonly used for nozzle classification and droplet spectrum comparison [11]. | Insufficient accuracy for gas-phase, non-spherical droplets; overestimates fine droplet proportion in cases with speed differences and low wind speed. |

| Laser Imaging | Captures scattered light images of droplet clusters, extracts grayscale centroids and boundaries, constructs drift index (DIX) and characteristic height. | Wind tunnel and field drift assessment | Can quantitatively characterize drift rate, drift height, and distance; high correlation between DIX and deposition rate (R > 0.9). | Affected by ambient light and background aerosols; needs mutual calibration with sampling methods and LD/PDPA results. |

| LiDAR | Emits pulse laser and receives echo to construct pseudo-3D/3D point cloud fields. | Wind tunnels, fields, large-scale drift monitoring, buffer zone evaluation | Large range, high spatial resolution, real-time drift potential monitoring (DP, DPRP), can differentiate nozzle and airflow differences [74] | Expensive; only sensitive to “surface clouds”; small droplets and far-side clouds are easily blocked; sensitive to humidity and aerosols, data interpretation is complex. |

| Laser Scanning (Line Laser + Camera) | Laser line forms 2D cross-section; UASS or sprayer moves according to planned trajectory, reconstructing 3D cloud via time-space mapping. | Three-dimensional droplet distribution, spray width structure analysis | Simple hardware, low cost, high spatial resolution, consistent with CFD wind field; can supplement LiDAR for medium-scale analysis [54]. | Limited sensitivity to droplet size; high-power lasers pose safety risks; requires optimization of angle and background obstruction. |

| PIV | Tracks tracer particle displacement, calculates velocity vectors and vorticity fields. | Rotor wind fields, canopy disturbances, wind tunnel validation | Visualizes downward flow and vortex structures, reveals interactions between wind fields and droplets; can be verified with CFD. | Tracer placement is complex, applicable range limited by field of view and optical conditions; difficult to cover large-scale fields. |

| Multi-source Fusion Visualization | Synchronously triggers PDIA/high-speed imaging and PIV/LiDAR to achieve spatiotemporal registration and data fusion. | Wind tunnel-field integrated research, wind-droplet-target coupling analysis | Monitors the entire process from droplet-wind-field-deposition, revealing spatial correspondence between deposition hotspots and vortex structures. | System synchronization and data fusion algorithms are complex; high hardware and computational power requirements. |

| Field Rapid Detection (Smart Terminals) | Uses smartphones or portable devices to capture spray images, analyzing spray angles, spray width, and nozzle consistency. | Field quality control, pre-operation inspection, nozzle screening | Portable and quick, low cost, suitable for equipment quality inspection and rough state evaluation [71]. | Limited accuracy, suitable only for geometric and pattern detection, difficult to provide standardized droplet size data. |

| Platform Type | Typical Operating Conditions and Scenarios | Observable Indicators | Advantages | Limitations | Representative References (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Wind Tunnel (Small Cross-section) | Fixed nozzle/small spray bar, conducting droplet spectrum and drift testing under controlled wind speed, temperature, and humidity. | Droplet size distribution, lateral distribution, near-field drift amount. | Controlled conditions, high repeatability, suitable for single-factor analysis. | Limited space, difficult to replicate UASS scale and rotor wind fields. | Liu et al., 2021 [85] |

| Semi-open/Large Wind Tunnel (EoleDrift, etc.) | Artificial orchard obstacles installed, UASS/airblast tested under forced crosswind to assess drift height distribution and drift reduction techniques. | Height distribution, total drift index, nozzle/height comparison. | Simulates real orchard conditions in a controlled environment with unified evaluation metrics. | Expensive equipment, fixed spatial layout, limited representativeness for complex terrain. | Delpuech et al., 2022 [51] |

| Artificial Orchard + Field Trials | Artificial vineyard or simulated fruit tree clusters, UASS low-altitude spraying with various types of samplers set up. | Canopy deposition, ground settlement, airborne drift, mass conservation. | Balances controlled structure with field wind environment, suitable for mass balance analysis. | Incomplete meteorological control, long trial period, high labor costs. | Wang et al., 2021 Cui et al., 2025 [50,86] |

| Field Trials (Natural Orchards/Farmland) | UASS or spray bar spraying at real orchards or farmlands, deposition boards and drift sampling lines set up. | Deposition, drift distance, and distribution under real operational conditions. | Closely mimics actual production conditions, results directly applicable to technical promotion evaluation. | High meteorological randomness, poor repeatability of trials; difficult to analyze fine mechanisms. | Shi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2019 [87,88] |

| LD/PDPA Indoor Droplet Size Test Bench | Droplet size testing under standard nozzles, fixed pressure, and flow conditions. | Dv10/50/90, RSF, droplet spectrum variations. | Mature technology, high accuracy, basis for nozzle calibration and droplet spectrum comparison. | Cannot provide spatial structure and wind field effects; difficult to directly extrapolate to UASS rotor scenarios. | De Cock et al., 2016 [66] |

| HSI/DIH Optical Platform | Visualizes liquid film breakage, droplet formation, and local 2D/3D field distributions in a small range. | Droplet size, speed, 3D position, local droplet morphology. | Can analyze breakage mechanisms and local dynamics, supports ML/AI analysis. | Limited field of view, difficult to cover entire spray width or large-scale drift. | Kumar et al., 2024 [55] |

| LiDAR 3D Scanning Platform (Ground-mounted) | LiDAR installed at fixed locations, scanning airblast or orchard sprayer drift plume in real-time. | Plume shape, width, central position, relative concentration. | Long-range, non-contact, real-time measurement without interfering with spray process. | Limited sensitivity to small droplets and low-density clouds; measures only “surface clouds.” | Gil et al., 2013; [74] |

| LiDAR + Motion Scanning (3D Reconstruction) | Spray machine or LiDAR moves via mechanical motion/operation to complete volume scanning and obtain 3D point cloud. | Three-dimensional point cloud, droplet cloud surface, spatial distribution. | Large-scale 3D droplet cloud measurements, suitable for analyzing wind-blown structures and nozzle position effects. | Complex data processing, high synchronization and registration accuracy requirements. | Wang et al., 2023 [75] |

| Laser Slicing Imaging + UASS Scanning | Laser line forms 2D cross-section, UASS moves according to planned trajectory to reconstruct 3D cloud field. | Three-dimensional point cloud, relative density, structural differences in machine types. | Relatively simple hardware, suitable for UASSs, high spatial resolution. | Limited droplet size sensitivity, high-power lasers require safety protection. | Wang et al., 2024 [54] |

| X-ray Imaging Test Bench | X-ray source and detector arranged in a controlled site to observe spray flow after penetrating canopy. | Mass flux, penetration rate, post-target drift risk. | Strong penetration capability, can directly quantify mass drift and canopy penetration. | Expensive equipment, high safety requirements, unsuitable for large-scale and routine applications. | Heindel, 2018; Qiu et al., 2023 [89,90] |

| UASS-specific Composite Platform (Wind Tunnel + Rotor + Crosswind) | UASS fixed or partially moving, applying crosswind and rotor downwash in the wind tunnel. | Drift amount under composite wind fields, height distribution, pressure/wind speed interaction. | Controlled conditions, includes real rotor effects, important for UASS drift mechanism research. | Limited space, machine and parameter combinations still need simplification; difficult to fully represent field unstable wind fields. | Zhang et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023 [91,92] |

| Type | Characteristic Quantity | Meaning and Function | Typical Measurement Methods | Representative References (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet properties | Dv10 | Droplet size corresponding to 10% volume fraction, used to describe fine droplets, sensitive to drift risk. | Laser diffraction, PDPA, HSI/DIH | De Cock et al., 2016; Tuck et al., 1997 [66,104] |

| Dv50 (VMD) | Median diameter of volume distribution, core indicator of droplet coarseness. | LD, PDPA, imaging/DIH | Tuck et al., 1997 [104] | |

| Dv90 | Droplet size corresponding to 90% volume fraction, used to describe coarse droplets, sensitive to deposition ability. | LD, PDPA, DIH | De Cock et al., 2016 [66] | |

| RSF (Relative Span) | (Dv90–Dv10)/Dv50, describes droplet spectrum width, related to droplet polydispersity and deposition distribution uniformity. | LD, PDPA, image analysis | Tuck et al., 1997 [104] | |

| D32 (Sauter Mean Diameter) | Equivalent diameter linking volume and surface area, represents mass transfer/evaporation and deposition processes. | PDPA, DIH, image analysis | Kumar et al., 2024 [55] | |

| Droplet Number Density/Volume Fraction | Number or volume fraction of droplets per unit volume, basis for constructing mass flux and risk assessment. | DIH, HSI, X-ray, LiDAR/laser imaging | Kumar et al., 2024; Heindel, 2018 [55,89] | |

| Droplet Morphology/Breakage Mode | Liquid film, filaments, agglomerated droplets, related to nozzle internal flow patterns and breakage mechanisms. | HSI, image pattern recognition | Kumar et al., 2024 [101] | |

| Aerodynamics | Downwash Velocity Field (u, w) | Rotor-induced 3D velocity field, determines droplet initial acceleration and down/upward trends. | PIV, hot-wire/Doppler, CFD + experimental inversion | Liu et al., 2021 [85] |

| Vortex Strength/Vorticity | The strength and scale of wingtip vortices, directly affecting droplet entrainment and upward drift. | PIV, CFD, rotor wind tunnel experiments | Wang et al., 2021 [21] | |

| Vortex Core Location and Trajectory | The spatial path of vortex cores, determining the position and height of secondary upward drift. | PIV, CFD configuration, laser imaging comparison | Liu et al., 2021 [85] | |

| Downwash–Crosswind Angle | The resultant flow direction after combining external wind field and rotor downwash, influencing drift main direction and plume deflection. | Wind tunnel tests, on-site meteorological measurements + UASS posture recording | Delpuech et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021 [51,85] | |

| Spatial structure | Plume Width | The lateral expansion scale of the droplet cloud, key parameter for safety buffer zone and spray width coverage. | LiDAR, laser slicing imaging, DIH 3D field | Gil et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2024 [54,74] |

| Plume Centroid Position | The position of the droplet cloud’s center in horizontal and vertical directions, representing overall drift tendency and lift. | LiDAR point cloud reconstruction, laser imaging, 3D DIH | Gil et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2023 [74,75] | |

| Three-dimensional Droplet Density Field/Voxel Occupancy | The distribution of droplets in 3D space and local enrichment areas, basis for constructing 3D drift models and canopy penetration analysis. | LiDAR 3D scanning, DIH, laser plane scanning | Wang et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023 [54,55,75] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Zhuo, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, P.; Li, X.; Tao, M.; Cui, Z. Visualization Techniques for Spray Monitoring in Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems: A Review. Agronomy 2026, 16, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010123

Ma J, Zhuo H, Wang P, Chen P, Li X, Tao M, Cui Z. Visualization Techniques for Spray Monitoring in Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems: A Review. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010123

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Jungang, Hua Zhuo, Peng Wang, Pengchao Chen, Xiang Li, Mei Tao, and Zongyin Cui. 2026. "Visualization Techniques for Spray Monitoring in Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems: A Review" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010123

APA StyleMa, J., Zhuo, H., Wang, P., Chen, P., Li, X., Tao, M., & Cui, Z. (2026). Visualization Techniques for Spray Monitoring in Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems: A Review. Agronomy, 16(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010123