1. Introduction

Oudemansiella raphanipies is a precious edible mushroom that not only contains essential nutrients such as protein, fat, amino acids, and various vitamins but also contains certain amounts of polyphenols and polysaccharides [

1]. Additionally, its unique flavor, rich nutritional value, and excellent antioxidant activity are making it increasingly popular among consumers. Thus,

Oudemansiella raphanipies has gained popularity as a cultivated crop among mushroom farmers. However, the surge in

Oudemansiella raphanipies production has intensified post-harvest packaging and processing difficulties, attributable to its high water content and absence of epidermal tissue. Post-harvest delays in packaging and storage accelerate quality loss in mushrooms, adversely impacting their marketability and farmer incomes. This is also one of the key factors hindering the rapid development of the

Oudemansiella raphanipies industry.

Typically, the packaging of post-harvest agricultural products is based on mass. To improve the weighing efficiency, electronic weighing equipment is used to replace traditional mechanical weighing devices [

2]. However, during the operation process, workers may cause physical damage, which further reduces the value of samples. With the rapid development of computer vision technology, non-destructive mass estimation has emerged as the predominant methodology. One method is to determine the mass of the sample by measuring its volume. This approach relies on the principle that the density of a homogeneous material is constant, implying a direct proportional relationship between the volume and mass. Currently, researchers have achieved satisfactory accuracy in the volume measurement of many agricultural products, such as watermelon [

3], apple [

4], egg [

5,

6], orange [

7], cucumber, and carrot [

8]. Another method is to estimate the mass of samples via a regression method based on phenotypic parameters. Similarly, many researchers have successfully developed regression models to estimate the mass of agricultural products, such as apple [

9], kiwi fruit [

10], tomato [

11], and potato [

12]. In contrast to other agricultural products,

Oudemansiella raphanipies is not symmetrical, and there are undetermined hollowed-out areas at the bottom when they are processed on the conveyor belt. Therefore, it is difficult to measure the volume of

Oudemansiella raphanipies directly via image-based methods; thus, the approach of estimating the mass via the volume is not suitable. From another perspective, owing to the distinct morphological characteristics of

Oudemansiella raphanipies compared to conventional agricultural commodities, regression models relying exclusively on basic phenotypic parameters (e.g., length and width) exhibit substantial errors in mass estimation. Furthermore,

Oudemansiella raphanipies is commonly handled in batches rather than processed individually in practical production due to the small sizes of individual units. Consequently, it is necessary to design a new means to obtain the mass of a batch of

Oudemansiella raphanipies in a rapid and accurate manner. For this purpose, the task can be divided into three subtasks, namely the segmentation of multiple samples, the extraction of multiple complex phenotypic parameters, and the selection of appropriate parameters and approaches for mass regression.

The separation of samples is an instance segmentation task in the field of computer vision. With the development of computer hardware and deep learning, various instance segmentation networks have rapidly emerged, such as Mask R-CNN [

13], YOLACT [

14], SOLOV2 [

15], and Mask R-CNN with Swin [

16]. These approaches have achieved impressive performance in the agriculture field. For instance, Yang et al. [

17] and Li et al. [

18] applied Mask R-CNN to segment soybean to calculate its phenotypic parameters, and the experimental results showed that the method is robust in segmenting targets, even under densely cluttered environments. Sapkota et al. [

19] compared YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN with immature green fruit and trunk and branch datasets. The experimental results showed that both of them effectively segmented apple tree canopy images from both the dormant and early growing seasons, and YOLOv8 performed slightly better in different environments. Moreover, to solve the problem whereby rice field detection technology cannot be adapted to the complexity of the real world, Chen et al. [

20] considered the rice row detection problem as an instance segmentation problem and successfully implemented a two-pathway-based method. However, the application of these advanced methods in the field of edible mushrooms is scarce, especially for

Oudemansiella raphanipies.

For the phenotypic parameters subtask, recent advances in computer vision and deep learning techniques have enabled the application of automatic phenotype extraction in agronomy. Yang et al. [

17] applied principal component analysis (PCA) to correct the pod’s direction and then calculate the width and length of the pod. The results showed that the average measurement error for pod length was 1.33 mm, with an average relative error of 2.90%, while the pod width had an average measurement error of 1.19 mm and an average relative error of 13.32%. Except for length and width, He et al. [

21] extracted the pod’s area using the minimum circumscribed rectangle method combined with the template calibration method, and the results showed that the accuracy of the pod area was 97.1%. Additionally, Liu et al. [

22] proposed a core diameter

Ostu method to judge the posture and then obtained the length, surface area and volume, which were calculated by the elliptic long and short axes of the cross section of the silique. The experimental results reported that the errors of all phenotypic parameters were less than 5.0%. To meet the phenotypic information requirements of

Flammulina filiformis breeding, Zhu et al. [

23] utilized image recognition technology and deep learning models to automatically calculate phenotypic parameters of

Flammulina filiformis fruiting bodies, including cap shape, area, growth position, color, stem length, width, and color. Furthermore, some studies apply the extracted phenotypic characteristics to other tasks. Kumar et al. [

24] extracted the centroid, main axis length, and perimeter of plant leaves and then combined them with multiple classifiers to achieve classification. The accuracy of this method can reach 95.42%. Moreover, Okinda et al. [

25] fitted the egg to an ellipse using the direct least square method and then extracted 2D features of the ellipse, such as area, eccentricity and perimeter, to establish the relationship between these parameters and the product’s volume using thirteen regression models, achieving excellent results in volume estimation of the egg. However, although the previous studies have obtained the basic parameters of

Oudemansiella raphanipies like length and width [

26,

27], these characteristics cannot fully represent the morphology of

Oudemansiella raphanipies. Thus, to obtain an accurate mass result, more complex phenotypic parameters of

Oudemansiella raphanipies need to be calculated.

For the mass estimation subtask, existing research has primarily focused on mathematical model-based methods and regression-based methods. Due to the irregularity of agricultural products, more and more regression-based methods have been used. For instance, Nyalala et al. [

28] directly fed five phenotypic parameters of tomato (area, perimeter, eccentricity, axis-length, and radial distance) into a support vector machine (SVM) with different kernels and an artificial neural network (ANN) with different training algorithms models to predict its mass. The experimental results showed that the Bayesian regularization ANN outperformed other models, with a root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.468 g. Nevertheless, this approach neglected feature redundancy and correlations between predictors and target variables. To make up for this insufficiency, Saikumar et al. [

29] calculated a high linear correlation between the mass and the length, width, perimeter, and projection area first with a correlation coefficient of 0.96, 0.92, 0.92, and 0.95, respectively, and built multiple univariate and multivariate regression models for elephant apple (

Dillenia indica L.) mass prediction. The results showed that the multivariate rational model performed the best, with an RMSE of 18.196 g. However, this simplistic variation in input combinations did not consider potential redundancy among the input parameters, which could lead to suboptimal model performance. Moreover, the performance of regression models varies depending on the target. Consequently, to accurately predict the mass of

Oudemansiella raphanipies, it is essential to explore optimal model selection and feature optimization strategies.

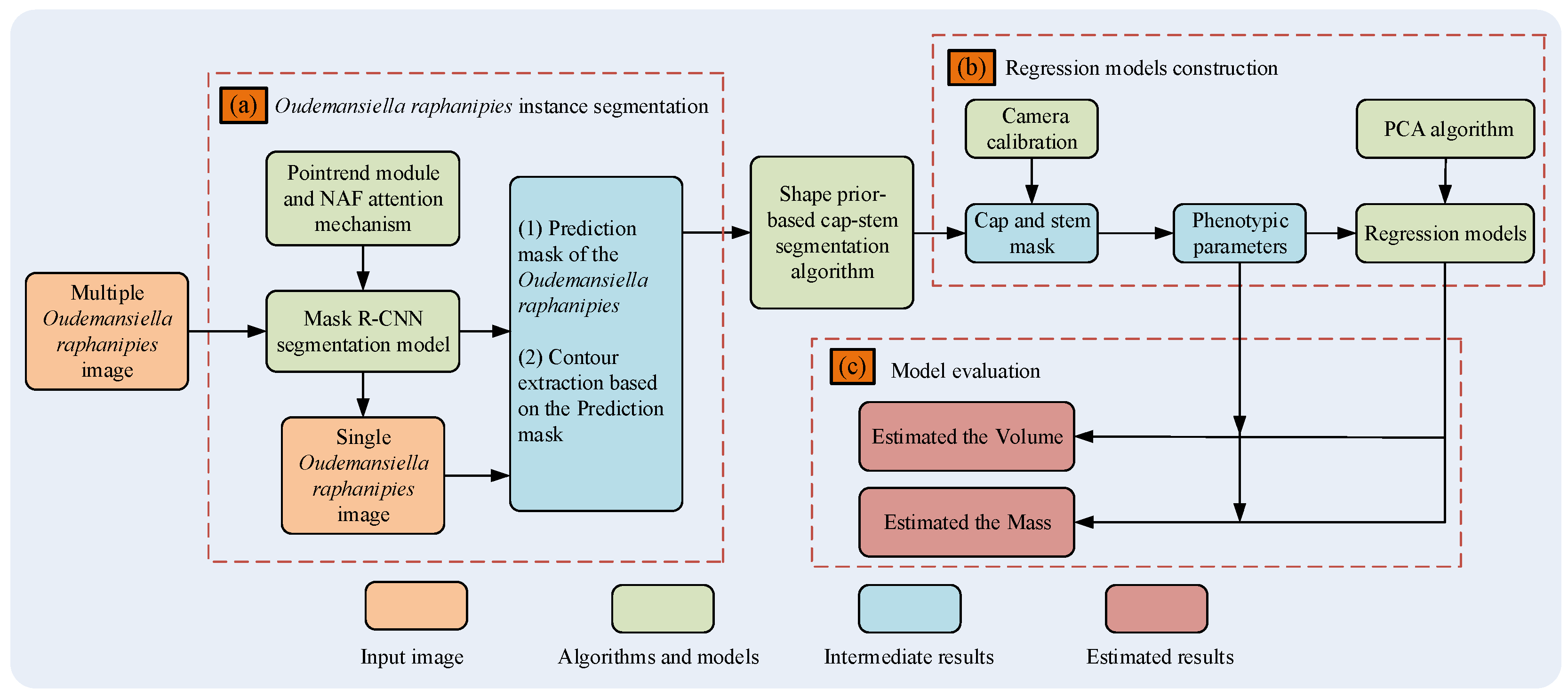

In this study, we implemented a machine learning- and deep learning-based framework for estimating the mass of a batch of Oudemansiella raphanipies. The main contributions are as follows:

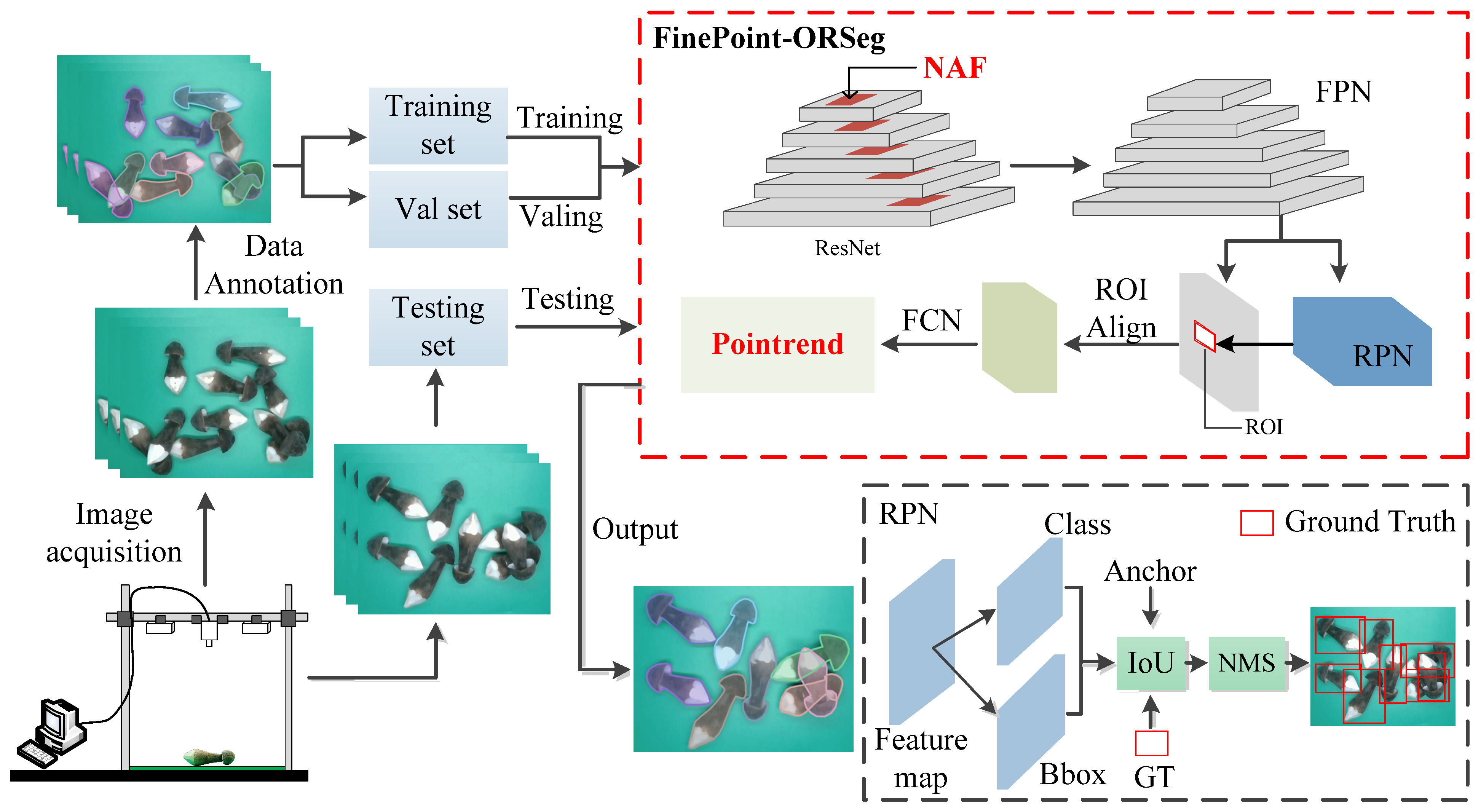

(1) A dataset including 1201 images was constructed and a novel instance segmentation network for Oudemansiella raphanipes Segmentation (FinePoint-ORSeg) was applied to obtain the individual sample;

(2) A novel stem–cap-based segmentation method was proposed for extracting phenotypic parameters robustly, and 18 phenotypic parameters were extracted;

(3) We evaluated the performance of various mass regression methods and the best means of calculating the mass of multiple Oudemansiella raphanipies was determined.

4. Discussion

Regarding the

Oudemansiella raphanipies instance segmentation task, we integrated the NAF module and the PointRend module into the FinePoint-ORSeg network to improve the segmentation capabilities and address the issue of rough target boundaries during inference. Specifically, NAF helps the network maintain an awareness of the overall morphology and spatial distribution of the targets while extracting local details, while PointRend significantly improves the geometric accuracy of the segmentation masks, which is particularly important for subsequent geometry-based volume estimation, thereby improving the model’s robustness in complex scenarios.

Table 4 shows that adding only the NAF or PointRend module could improve the average precision, which demonstrates its contribution to high-precision mask generation.

Table 5 shows a similar performance to other state-of-the-art works based on DL which reported an AP result of 0.831.

The main contribution of this work is the phenotypic parameters extraction algorithms and the use of ML to estimate the

Oudemansiella raphanipies (mass and volume) even in the presence of multiple targets. The results (

Table 6) show that the phenotypic parameters extraction algorithm was able to robustly obtain features such as CD (MAE = 1.01 mm), CH (MAE = 0.73 mm), SD (MAE = 1.30 mm) and SH (MAE = 0.58 mm). Compared with other state-of-the-art results that measure the CD of

Oudemansiella raphanipies [

26,

27], this study achieved MAE values of between 0.35 mm and 2.30 mm and is considered as an accurate and acceptable results and achieved. However, it is notable that the error (

Table 6) of the number 1 (MAPE = 13.26%) and 8 (MAPE = 11.39%) of CD, the number 2 (MAPE = 11.30%) of CH and the number 7 (MAPE = 10.71%) of SD were significantly higher than other

Oudemansiella raphanipies. The main reasons are as follows: (1) Error introduced by manual measurement. Since the

Oudemansiella raphanipies is a non-rigid object, compression may occur during measurement, leading to an underestimation of the reference value. Additionally, the determination of measurement points manually involves a certain degree of subjectivity. (2) Error introduced by the view angle of measurement. Due to the irregular shape of the

Oudemansiella raphanipies and the fact that the manual measurement perspective is different from the camera’s perspective, there is a discrepancy between the manual measurement and the system’s measurement results. (3) Error introduced by our extraction approach. Due to the significant influence of external environmental factors on the shape of the

Oudemansiella raphanipies, some instances have large caps but narrow stems, while others have small caps but thick stems. As a result, our segmentation method based on the angle between the stem and cap requires different threshold values for the latter case, which would also cause errors in the phenotypic parameters’ extraction.

The correlation analysis results show that RDH, roughness, and ARMB have low correlations with mass and volume. Therefore, the performance of nine machine learning models was compared under different numbers of principal components, and the Exponential GPR was finally selected as the subsequent basic model. Furthermore, the Exponential GPR was applied to evaluate the samples in different states. The experiments show that the CV of instance number 9 and 18 for single samples (

Table 6) and the accuracy of image numbers 5 and 9 for multiple samples (

Figure 14b) have unsatisfactory results.

Figure 16 depicts the CV of 18 phenotypic parameters extracted from the above samples. It can be seen that the Angle and Total Area of the No.9 sample have a relatively larger error of 8.97% and 9.12% compared with other features. Moreover, the opening angle, perimeter and total area also have a relatively larger error. For three samples of different grades, all of the opening angles obtain a CV exceeding 5%. This indicates a relatively large volatility, which might be an important reason for the significant difference in the prediction results of the two images. In addition,

Table 8 shows that the MAPE of the large samples is 5.32% and 4.80% lower than average error for mass and volume, respectively, and this means that the economic loss can be reduced by 9.77%.

The phenotypic parameters extracted in this work were obtained with 2D image and calibration at fixed height, which limited the data precision and the number of features. The use of 2.5D or 3D data would provide higher precision for subsequent estimation. However, the Oudemansiella raphanipies is relatively small in size, so higher-precision depth cameras or three-dimensional phenotypic extraction methods need to be adopted. In addition, the phenotypes of Oudemansiella raphanipies of different varieties and in different planting environments vary greatly. Therefore, it is urgent to develop an adaptive phenotypic parameter extraction method with high robustness.