1. Introduction

Global agriculture is increasingly threatened by multiple interacting pressures, including rising heat and drought stress under climate change, the continuous decline of arable land, and escalating energy costs. Agrivoltaics (APV), a dual-use land system in which photovoltaic (PV) modules generate electricity while crops are grown beneath or between the panels, has been highlighted as a promising technology for sustainable agricultural transitions [

1,

2]. Previous studies have demonstrated that APV can moderate excessive solar radiation, reduce surface temperatures by 2–4 °C, and alleviate heat stress on crops, thereby maintaining or enhancing yield performance [

1,

2]. Furthermore, APV systems can produce approximately 150–300 MWh ha

−1 of annual electricity while contributing to on-farm renewable energy supply [

2,

3]. By allowing simultaneous electricity generation and food production, APV increases land-use efficiency; Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) values of 1.2–1.7 have been reported, demonstrating more efficient land-use than monocropping systems [

2]. From a Food–Energy–Land nexus perspective, APV offers substantial potential to support climate-resilient and resource-efficient agricultural systems.

However, existing APV research is overwhelmingly concentrated in temperate regions such as Europe, North America, and East Asia, while empirical data from tropical monsoon climates—characterized by high temperature, high humidity, and reduced or variable light conditions—remain extremely limited [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Soybean (Glycine max), a globally important protein and feed crop, is highly sensitive to heat stress; temperatures above 33–36 °C during flowering and early pod formation suppress floral and microspore development, reduce pod set, inhibit seed filling, and consequently lower yield by 20–40% [

8,

9,

10]. Despite this strong heat sensitivity, empirical studies evaluating how APV modifies soybean microclimate and the associated physiological responses, as inferred from changes in phenological development and productivity, under tropical monsoon conditions remain extremely limited, representing one of the most significant gaps in current APV research.

Bogor, located in West Java, Indonesia, exhibits a typical tropical monsoon (Am) climate with high mean annual temperatures (26–28 °C), substantial annual rainfall (3000–3500 mm), more than 270–300 rainy days per year, and consistently high relative humidity (>80%) [

11,

12,

13]. Distinct wet (November–April) and dry (June–September) seasons lead to strong seasonal contrasts in solar radiation, rainfall, and temperature regimes. During the dry season, maximum temperatures rise to 32–34 °C and solar irradiance frequently reaches 500–600 W m

−2, conditions known to induce heat and light stress in soybean and contribute to reduced growth, pollen sterility, impaired seed development, and yield losses of up to 20–35% [

8,

14,

15]. More than 90% of soybean cultivation in the Bogor region occurs in open-field systems [

16,

17], making the area highly suitable for evaluating APV-mediated microclimate modification and its potential to buffer soybean growth and yield against tropical stress conditions. Moreover, the Indonesian government has positioned APV as a key strategic technology to achieve its renewable energy target of 23% by 2025 and carbon neutrality by 2060 [

4,

5,

18], further emphasizing the need for research on APV deployment in tropical climates.

Therefore, this study evaluated the microclimate (solar radiation, air temperature, soil temperature and moisture), growth traits, phenology, and yield components of soybean grown under APV and open-field conditions during one wet season and one dry season cropping cycle in Bogor, Indonesia. The objectives were to (1) quantify the effects of APV on soybean physiology, growth, and yield under tropical monsoon conditions, (2) assess the extent to which APV mitigates heat and radiation stress prevalent during the dry season, and (3) evaluate the potential of APV to stabilize soybean productivity amid increasing heat risks under climate change. By addressing the scarcity of empirical soybean–APV data from tropical regions, this study provides essential scientific evidence for expanding APV-based food–energy–land integration in low-latitude agricultural systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Site Conditions

The field experiment was conducted at the Cikabayan Experimental Farm of IPB University, located in Bogor, West Java, Indonesia (6°33′08″ S, 106°43′00″ E; elevation 171 m). Two soybean (‘Detap-1’, a commonly used Indonesian variety) cropping cycles were implemented: the first during the wet season (January–March 2025) and the second during the dry season (July–September 2025). The study area is characterized by an Am climate with pronounced seasonal variability in rainfall, solar radiation, and temperature. It should be noted that the designation of dry season in this tropical environment refers to the period of lower average monthly rainfall, although substantial total rainfall may still occur, distinguishing it from temperate dry seasons.

The daily temperature and rainfall conditions during wet season (A) and dry season (B) cropping periods are presented in

Figure 1. The wet season cultivation lasted 83 days, during which the mean, maximum, and minimum air temperatures were 25.9 °C, 34.0 °C, and 20.9 °C, respectively. Total rainfall amounted to 1272 mm, and rainfall events exceeding 1 mm occurred on 45 days. In contrast, the dry season cultivation spanned 79 days, with mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures of 26.1 °C, 35.4 °C, and 20.2 °C, respectively. Total rainfall during this period was 1087 mm, and only 28 days recorded more than 1 mm of precipitation. Notably, rainfall in the dry season was highly concentrated on a few specific days—such as 18 July (46.1 mm), 30 July (95.7 mm), 1 September (69.0 mm), and 28 September (54.2 mm)—while most other days were rainless, reflecting the distinct precipitation pattern characteristic of the dry season environment. This pattern, characterized by fewer rainy days and intermittent heavy downpours, is the defining feature of the dry season in this region, despite the high cumulative rainfall.

Soils at the experimental site were classified as clay, with average texture values of 72.0% clay, 18.4% silt, and 9.6% sand within the sampled soil profile (0–50 cm). The soil was strongly acidic, with pH(H2O) ranging from 4.0 to 4.8 and pH(KCl) from 4.1 to 4.6. Electrical conductivity was low (26.5–65.2 μS cm−1), and organic carbon (1.28–2.24%) and total nitrogen (0.08–0.18%) were within moderate ranges. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) ranged from 15.98 to 23.95 cmol(+) kg−1, while base saturation (12.5–30.1%) and available phosphorus (Bray I, 0.61–8.48 mg kg−1) were low. Soil chemical properties were analyzed using depth-stratified soil samples collected at multiple depth intervals. Exchangeable K was also low (0.04–0.14 cmol(+) kg−1). Exchangeable Ca and Mg were relatively higher in the surface layer but declined with depth.

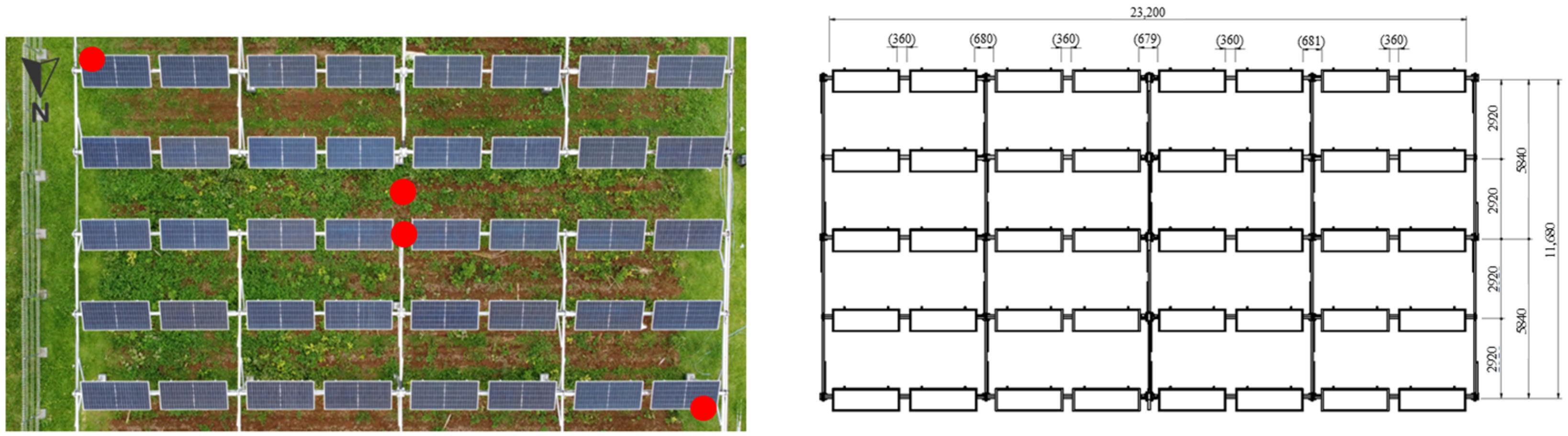

2.2. APV System Configuration and Experiment Design

The experiment consisted of two treatments: (1) an APV plot equipped with an overhead solar structure and (2) an open-field control without any above-ground installations. Each plot measured 25 m × 12.5 m (312.5 m2). Given the scale of the APV infrastructure, this study employed a single-plot-per-treatment design. Consequently, individual plant measurements were collected as subsamples within each treatment to assess variability, rather than serving as independent plot replications. Within each plot, eight crop rows were established. Soybeans were planted in double rows, with 50 cm between rows and 15 cm within rows, resulting in a target planting density of approximately 266,000 plants ha−1. Identical planting density and row arrangement were applied to both the APV and open-field plots to ensure uniform crop distribution across treatments.

The APV structure installed in the treatment plot was mounted at a uniform height of 3.1 m above the ground, allowing unobstructed field operations and soybean cultivation beneath the panels. The clearance height of the APV structure was designed to allow routine field operations beneath the panels, although no heavy mechanized harvesting was conducted during the experimental period. The photovoltaic modules used in the system measured 2465 mm × 1134 mm and were installed at a fixed tilt angle of 15°. The shading ratio, calculated based on the projected panel area and array configuration, was estimated at 34.9%. Detailed information on panel orientation, row spacing, and array layout is provided in

Figure 2.

2.3. Crop Management

Crop management practices were applied consistently across both the APV and open-field treatments and were maintained similarly during the two seasons cultivation cycles, except for differences in planting and harvesting dates. Soybean was established by direct seeding, with field planting conducted on 4 January 2025 for the wet season cycle and on 14 July 2025 for the dry season cycle. Two seeds were placed per planting hole at a depth of approximately 2–3 cm.

Prior to sowing, land preparation was carried out using a combination of mechanical and manual tillage to a depth of 20–30 cm (18–19 December 2024 for the wet season and 21 June 2025 for the dry season). Well-decomposed cow manure was applied as a basal amendment at a rate of 20 kg per furrow (27 December 2024 and 27 June 2025 for the wet and dry seasons, respectively) and incorporated into the top 10 cm of soil. Basal fertilization was applied at planting using granular compound fertilizer (500 g NPK plus 100 g KCl per furrow), followed by a second application five weeks after sowing with the same formulation and rate. The total nutrient input per cycle corresponded to approximately 80 g N, 80 g P2O5, and 180 g K2O per furrow, with dolomite applied as a soil amendment to correct soil acidity.

Irrigation was uniformly administered to both treatments using a manual sprinkler system at a rate of approximately 15 L per furrow, three times per week, throughout both cropping cycles. Pest management was conducted using Matador 25 EC insecticide, applied once per cycle with a handheld sprayer to accommodate the limited clearance beneath the APV structure. Harvesting was performed manually at physiological maturity, on 28 March 2025 for the wet season crop and on 29 September 2025 for the dry season crop, to avoid interference from the overhead PV panels.

2.4. Microclimate Monitoring

Microclimatic conditions were continuously monitored throughout both cropping seasons to characterize the environmental factors influencing soybean growth and yield. An automatic weather station (RK900-01, Rika Sensors, Changsha, China) was installed to record atmospheric variables at 1 min intervals, including air temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), atmospheric pressure (hPa), and solar radiation (W m−2). Subsurface variables—soil temperature (°C), volumetric water content (%), and soil electrical conductivity (dS m−1)—were also monitored. In the open-field control plot, an additional rainfall sensor was installed to quantify precipitation (mm) during both cropping seasons, while effective rainfall beneath the APV system was not directly measured.

A total of five monitoring points were established: four located directly beneath the APV structure at representative positions between panel rows (at the northwest and southeast corners and two central positions beneath the panel rows) to capture spatial variability, and one positioned 2 m outside the structure to represent open-field conditions. Atmospheric sensors were mounted at a height of 1.5 m above ground level, while soil sensors were installed at a depth of 15–20 cm.

To evaluate the overall microclimatic differences, data from the four under-panel monitoring points were averaged to represent the APV condition. Subsequently, daily mean values for both the APV and open-field treatments were calculated and used for all statistical comparisons.

2.5. Plant Growth and Yield Measurements

Soybean growth and yield traits were assessed during both the wet season and dry season experiments under the APV and open-field control treatments. Plants were randomly selected within each plot, with 24 plants sampled from the APV treatment (12 directly beneath the panels and 12 between panel rows) and 12 plants from the open-field control. Because no significant differences were detected between plants located directly under the panels and those between panel rows (p > 0.05), the mean of the two positions was used as the representative value for the APV treatment.

Phenological development was evaluated using the criteria of [

19], focusing on the R1 (begin flowering), R3 (begin pod formation), and R5 (begin seed filling) stages. These stages correspond to the period during which most soybean yield components are determined and are widely used as key checkpoints in soybean growth analysis [

20,

21]. All weight measurements were taken using mechanical scales (CAMRY 30 kg, Zhongshan Camry Electronic Co., Ltd., Zhongshan, China; FIVE GOATS 10 kg, Guangzhou Wuyang Scale Factory, Guangzhou, China) and an electronic scale (FLECO F-111, PT. Fleco Indonesia Electronics, Jakarta, Indonesia).

2.5.1. Wet Season

Plant growth and yield measurements were collected twice weekly from 4 weeks after sowing until harvest. The following variables were recorded:

Vegetative growth traits: plant height (cm) and number of nodes.

Phenology: days to R1, R3, and R5.

Yield components: grain yield (kg ha−1), number of pods per plant, number of seeds per pod, number of seeds per plant, 100 seed weight (g), seed weight per plant (g), and aboveground biomass (g plant−1).

These traits collectively capture 70–90% of soybean yield variation and are recognized as key determinants of final grain yield [

20,

22,

23].

2.5.2. Dry Season

During the dry season, plant measurements were streamlined to focus on yield-related variables most sensitive to microclimatic differences. Previous studies have shown that certain yield components, such as seeds per pod, display limited variability across environments and contribute minimally to yield differentiation [

21,

24]. In contrast, traits such as pods per plant, 100-seed weight, seed weight per plant, and biomass are repeatedly reported as primary determinants of soybean grain yield [

22,

23,

24]. Accordingly, only essential variables were retained. However, vegetative growth traits were measured consistently with the wet season.

Measurements were collected weekly from 7 days after sowing until harvest, and included the following:

Vegetative growth traits: plant height (cm) and number of nodes.

Phenology: days to R1, R3 (R5 progression was inferred through direct yield measurements at maturity).

Yield components: grain yield (kg ha−1), number of pods per plant, 100 seed weight (g), seed weight per plant (g), and aboveground biomass (g plant−1).

This streamlined measurement protocol improved field efficiency under dry season conditions while maintaining the capacity to accurately evaluate plant growth and yield responses.

Grain yield (kg ha

−1) was estimated by upscaling plant-level seed yield to the target planting density. Specifically, grain yield was calculated as

The harvest index (HI, %) was calculated as

Both seed and aboveground biomass weights were recorded immediately after harvest under the same moisture conditions, and no moisture content adjustment was applied in the calculation of HI.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All microclimate and plant measurement datasets were pre-processed in Microsoft Excel 2021, including the removal of missing values and the calculation of means and standard deviations. To evaluate treatment effects between the APV and open-field conditions, independent two-tailed t-tests were performed using JMP® version 17.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Prior to analysis, tests for homogeneity of variance were conducted to verify the assumption of equal variances. However, given the single-plot-per-treatment design, these statistical comparisons should be interpreted as exploratory, reflecting within-plot variability rather than true plot-level replication. Statistical significance was assessed at the 1% and 5% levels, and the following notations were used to indicate significance in tables and figures: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and n.s. (not significant).

4. Discussion

4.1. Microclimate Moderation and Its Physiological Implications

Our study confirms that the APV system creates a distinct microclimate characterized by reduced solar radiation, lower soil temperatures, and higher soil moisture, consistent with findings from both temperate and arid environments [

25,

35]. However, the physiological implications of these changes in a tropical monsoon climate differ significantly from those in high-latitude regions.

In temperate zones, light reduction by APV often limits photosynthesis and yield because solar radiation is a primary limiting factor [

36]. In contrast, our results in Bogor suggest that the about 35% shading provided by the APV structure acted as a protective buffer rather than a limiting factor. Notably, while the maximum air temperature was significantly higher under the APV structure due to localized heat accumulation—likely caused by the resistance of the PV array to airflow [

28,

29]—this did not translate into yield penalties. Instead, the “cooling effect” was primarily manifested in the soil thermal environment. The significantly lower soil temperatures under APV (

p < 0.001) likely protected the root system from thermal stress, preserving root functionality and water uptake capacity during the hottest periods of the day.

During the dry season, the “water-saving effect” of APV—evidenced by significantly higher soil moisture (

Table 1)—became a critical driver. This aligns with Barron-Gafford et al. [

35], who demonstrated that APV shading reduces evapotranspiration demand, thereby decoupling crop production from immediate precipitation deficits. This moisture conservation mechanism explains why the APV plot maintained high vegetative growth and yield even during the water-limited dry season.

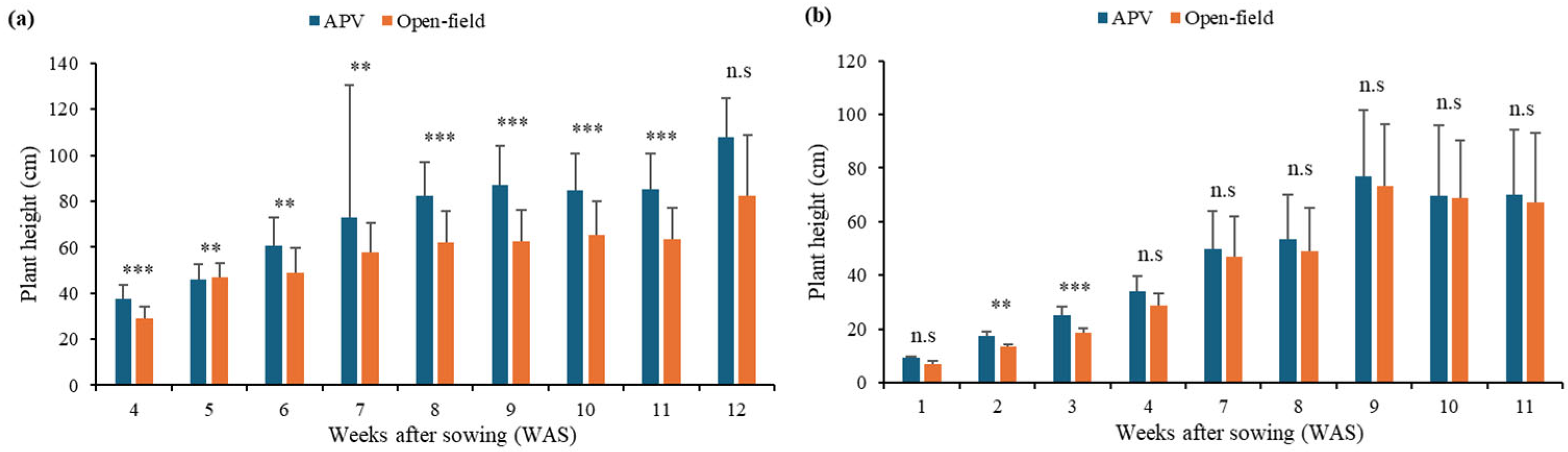

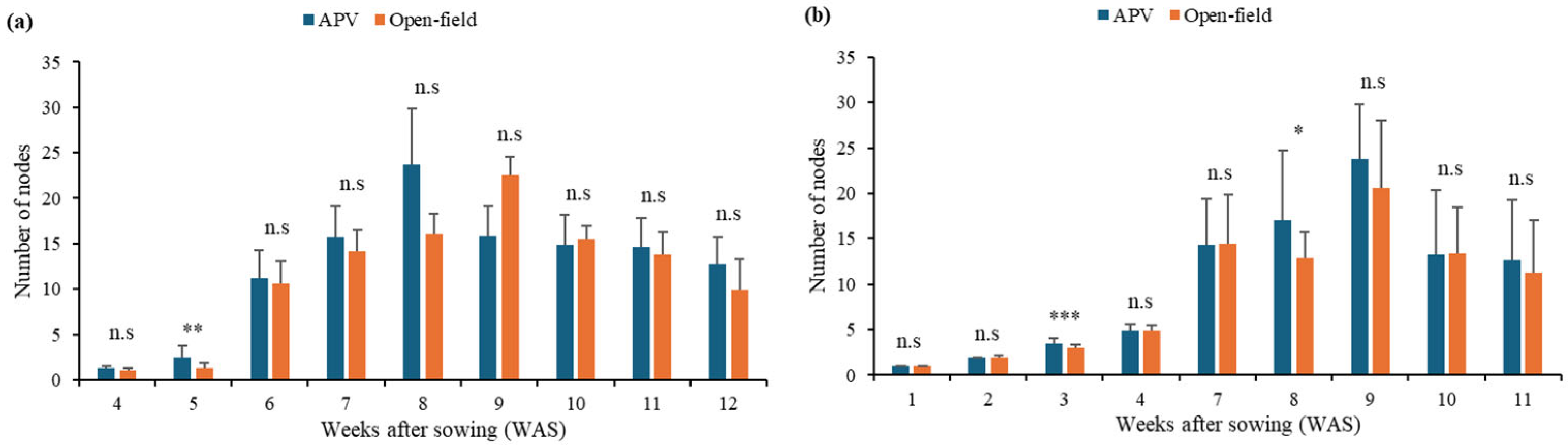

4.2. Phenological Stability and Vegetative Plasticity

A major concern in APV cultivation is that shading may delay flowering or induce excessive stem elongation (Shade Avoidance Syndrome, SAS), potentially leading to lodging and yield loss [

37]. However, our data showed no significant delay in phenological development (R1–R5) in either season (

Figure 3). This supports the photothermal theory of soybean development, which posits that flowering is primarily regulated by photoperiod and temperature accumulation rather than irradiance intensity, provided light levels remain above the compensation point [

19,

30].

Interestingly, while APV plants exhibited greater height and leaf area in the vegetative stages, this vegetative plasticity did not result in negative agronomic traits. Instead, the significantly higher aboveground biomass (

p = 0.001) and maintained node number in the wet season (

Figure 5) suggest that the shade level (about 35%) was within the acclimation capacity of the ‘Detap-1’ cultivar. This finding contrasts with studies using denser shade (>50%), where significant reductions in node number and biomass have been reported [

38]. It suggests that the specific APV design used in this study (sparse array, 3.1 m height) provides a balanced light environment that promotes vegetative vigor without compromising structural integrity.

4.3. Yield Formation Mechanism: Radiation Use Efficiency vs. Stress Mitigation

One of the most notable findings of this study is the significant yield advantage of APV observed in the wet season (+106%) and the moderate increase in the dry season (+17%). This result differs from the general trend observed in global APV meta-analyses, which often report yield penalties for major grain crops due to light limitation [

36,

39]. The mechanism behind this “tropical APV advantage” can be explained by the alleviation of environmental extremes.

Recent APV studies have emphasized that APV systems do not simply reduce total light availability but fundamentally modify the radiation regime at canopy level by attenuating excessive direct irradiance and increasing the proportion of diffuse radiation [

40,

41]. Such radiation modulation can enhance radiation use efficiency and mitigate photo-inhibition under high-radiation environments, particularly in warm climates.

In the wet season, the massive increase in number of pods per plant (72.2 vs. 43.9) under APV indicates that shading reduced reproductive abortion. Previous studies have established that heat and high-radiation stress during flowering (R1–R3) can significantly increase flower and pod shedding [

32]. By lowering the thermal load, the APV system likely allowed a higher proportion of flowers to set pods. This interpretation is consistent with findings from grape-based APV systems, where moderated radiation reduced canopy stress and sustained physiological activity despite partial shading [

41]. Furthermore, the significant increase in aboveground biomass implies that the open-field plants may have suffered from photoinhibition or saturation under intense tropical sunlight, whereas APV plants maintained efficient photosynthesis [

25,

33].

In the dry season, the higher HI under APV (36.2% vs. 30.3%) points to improved assimilate partitioning efficiency. Reference [

34] noted that under drought stress, soybean plants prioritize survival over seed filling, typically reducing HI. The fact that APV plants maintained a higher HI suggests they experienced less physiological water stress, allowing sustained photosynthate translocation to seeds [

27]. In this context, the reduced radiative and thermal load under APV likely contributed to maintaining photosynthetic function and carbon allocation efficiency under water-limited conditions, reinforcing the role of APV as a stress-buffering rather than light-limiting system. Thus, in tropical climates, the “stress-buffering” benefit of APV appears to outweigh the “light-limiting” cost, turning potential yield losses into significant gains.

4.4. Implications for Tropical Agrivoltaics

Our findings provide empirical evidence that APV is a highly viable strategy for sustainable intensification in tropical monsoon regions. Unlike in Europe or North America, where maximizing light transmission is the primary design constraint, tropical APV systems may benefit from shading levels that actively mitigate heat and drought stress. This “dual-benefit” creates a strong case for integrating energy generation with food production in Indonesia, contributing to the national renewable energy targets without compromising—and potentially enhancing—food security. Future research should focus on long-term soil health dynamics and the testing of diverse soybean genotypes to identify cultivars specifically adapted to the fluctuating light environments of APV systems.

In addition, this study focused on biophysical responses (microclimate and soybean performance) and did not quantify the structural resilience of the APV infrastructure or the techno-economic implications of below-PV cropping (e.g., wind-load design margins, CAPEX/OPEX, and machinery-related adaptation costs). Future work should integrate structural engineering assessments and comprehensive cost–benefit analyses to evaluate climate-resilient APV designs and adoption feasibility in tropical cropping systems. Therefore, future research should aim to extend these findings through multi-site, multi-year trials employing randomized complete block design (RCBD) across diverse agro-ecological zones. Such expanded studies would allow for a comprehensive assess (Dment of the interactions between APV shading, soil types, and regional microclimates, ultimately supporting the development of standardized guidelines for scaling up APV systems in Indonesia and the broader tropical region.

4.5. Engineering and Techno-Economic Considerations for Climate-Resilient Tropical Agrivoltaics

While this study primarily quantified microclimate modification and soybean responses under an overhead APV structure, successful scaling of tropical agrivoltaics as a climate-adaptation option also requires engineering robustness and operational feasibility. Agrivoltaics can increase agricultural resilience by buffering crops against severe weather and climate stressors, yet the PV infrastructure itself must remain reliable under increasing climate hazards and within real on-farm constraints [

42]. In particular, (i) wind/extreme weather risks for elevated structures, (ii) compatibility with farm machinery and field operations, and (iii) the cost premium and additional adaptation-related expenditures should be explicitly acknowledged when positioning tropical APV as a climate-resilient land-use strategy.

4.5.1. Wind/Extreme Weather Risk & Infrastructure Resilience

A climate-resilient APV concept should treat the PV structure not only as a shade provider but also as critical infrastructure exposed to extreme events. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report indicates with high confidence that the proportion of intense tropical cyclones and peak wind speeds of the most intense tropical cyclones will increase on the global scale with increasing global warming, while evidence for changes in severe convective-storm characteristics such as severe winds remains of low confidence beyond increased precipitation rates [

43]. Even when a specific inland site is not located in a primary tropical-cyclone belt, national or regional agrivoltaic deployment in tropical countries often includes coastal and archipelagic locations where extreme winds, gust fronts, and convective storm hazards can be relevant; therefore, robust wind design and operational risk management should be addressed as part of climate-resilient APV planning.

Elevated APV configurations are especially sensitive to wind loading. Design guidance for agrivoltaics notes that, as solar panels are installed higher off the ground, wind loading increasingly influences structural design, and rain/runoff effects can also affect land-management practices near panel edges [

44]. Thus, clearance height and structural geometry should be determined by agricultural needs (e.g., machinery passage, crop type) while avoiding unnecessary elevation that increases wind exposure. Lessons from post-storm PV assessments further emphasize that survivability depends strongly on robust module attachments, system geometry, and sturdy racking rather than relying solely on module pressure-load ratings [

45]. For elevated/canopy-like PV structures, excessive height can substantially increase wind loads; post-typhoon observations highlight that canopy systems built significantly higher than necessary were more susceptible to higher wind loads, and such structures should be built only as high as needed for their intended clearance [

45]. These insights are directly relevant to overhead agrivoltaics because the “below-PV cropping” configuration inherently requires elevated mounting systems.

In addition to structural design, climate resilience is also an operation-and-maintenance (O&M) issue. APV systems may face increased soiling and a higher risk of damage or corrosivity of PV components due to farming activities and agrochemical applications, which can influence both reliability and lifetime costs [

42]. Accordingly, climate-resilient tropical agrivoltaics should incorporate (i) region-specific hazard assessment and structural engineering consistent with applicable wind codes/standards, (ii) strengthened attachment and racking strategies suitable for elevated systems, and (iii) O&M protocols for inspection and rapid repair after extreme events to minimize downtime and safeguard long-term performance.

4.5.2. Machinery Compatibility and Operational Adaptations

Machinery compatibility is a decisive, often under-discussed constraint for overhead agrivoltaics. APV design guidance emphasizes that PV layout and infrastructure may need to be updated for safe agricultural operations, including panel height and spacing, cabling/wire depth, irrigation placement, equipment placement, and perimeter setbacks [

44]. Practical experience-based guidance also stresses that the APV mounting system should be aligned with the direction of tilling and that distances between supports must match the widths and heights of the machines used; impact protection on pillars can reduce damage risk during operations, and maneuvering between pillars requires an adaptation period for operators [

46].

Clearance height is the central design variable for below-PV cropping. A guideline example indicates that a system geometry of roughly 3.5 m × 4.2 m spacing with a clearance height of 3.2 m can enable the use of standard agricultural machinery while keeping cabling within the roof structure to reduce interference during field work [

46]. For stilted, overhead systems in arable farming, the clearance height is described as typically at least 5 m, with additional consideration needed for working width and headland space for machinery turning [

46]. Consistently, a techno-economic case study of an APV demonstration system reported a clearance height of 5 m specifically to avoid hindering agricultural machinery—particularly combine harvesting—highlighting that high-clearance designs are often chosen to minimize operational disruption in mechanized systems [

47].

Where local farming relies on smaller machinery or partially manual operations, alternative operational strategies may allow lower clearance heights and closer post spacing, potentially improving feasibility. In that regard, the agrivoltaics guideline notes that clearance height and post spacing strongly affect mounting-system cost and that using smaller farming machinery or performing more operations manually can improve cost-effectiveness [

46]. For tropical smallholder or mixed-mechanization contexts, climate-resilient APV deployment may therefore require (i) early-stage machinery surveys (dominant tractor size, sprayer/harvester dimensions, turning radius), (ii) explicit headland and trafficability planning, (iii) protective measures for posts and cabling, and (iv) operational protocols (e.g., designated driving lanes, GPS/precision guidance where applicable) to reduce collision risk and avoid soil compaction.

4.5.3. Cost Premium & Adaptation Cost Considerations

From a techno-economic perspective, overhead agrivoltaics generally involves a cost premium relative to conventional ground-mounted PV, primarily driven by modified mounting structures and added design/coordination requirements. A bottom-up cost benchmark of dual-use PV reported an installed cost premium of approximately 0.07–0.80 USD/WDC over conventional ground-mounted PV, with the highest premiums observed for PV + crop configurations due to modified PV support structures; it also noted that site investigation and design costs tend to be higher because dual-use projects require additional planning and coordination with stakeholders such as farmers [

48]. These findings align with broader agrivoltaic guidance describing that acquisition costs are generally higher than conventional ground-mounted PV—particularly for stilted, overhead systems—because of higher, more elaborate mounting systems and (in some designs) specialized PV modules [

46]. Importantly, as row spacing increases, land area requirements rise and costs can increase relative to electricity yield, creating a structural trade-off between agricultural operability (space/trafficability/light distribution) and energy/land-use efficiency [

46].

For “climate-resilient” tropical APV framing, the relevant economic question is not only the baseline APV premium but also the incremental costs of hardening systems for future climate hazards. Storm-resilience guidance for PV infrastructure indicates that selecting modules with the highest published design wind ratings can more than double module cost compared to cheaper alternatives (e.g., approximately 1 USD/W vs. 0.40 USD/W in one documented procurement context), and vibration-resistant hardware and additional labor can also add meaningful upfront premiums [

49]. While these figures are context-dependent, they illustrate that resilience measures can shift CAPEX and should be explicitly included in economic reasoning when responding to reviewer concerns about adaptation costs. Conversely, such costs may be justified by reduced repair needs, lower maintenance burdens, and improved ability to deliver power after severe-weather events—benefits that can be socially and economically valuable during climate-driven disruptions [

49].

A key implication for integrated PV + below-PV soybean systems is that techno-economic evaluation should account for both (i) energy revenue and system reliability and (ii) agricultural value and avoided losses under heat/drought extremes. The dual-use PV benchmark stresses that understanding capital costs is only a first step and that additional data—including crop yield changes, water-use efficiency impacts, and O&M costs—are needed to assess lifetime cost and revenue effects and to clarify the value proposition under different scenarios [

48]. Therefore, future tropical APV work would benefit from integrated analyses (e.g., scenario-based LCOE/NPV coupled with yield-stability benefits and risk-reduction under extreme climate events), explicitly separating (a) the baseline APV structural premium for below-crop operation and (b) incremental “climate-hardening” measures (wind/ corrosion/flooding/O&M) to provide transparent and decision-relevant evidence for policy and deployment.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides critical empirical data on soybean production under agrivoltaics in a tropical monsoon climate, certain experimental constraints inherent to commercial-scale infrastructure research should be noted. First, this study employed a single-plot-per-treatment design at a single site due to the logistical challenges and spatial requirements of installing a full-scale APV array. Accordingly, statistical analyses utilized plant-level subsamples (n > 100) as observational units. This approach was effective in rigorously capturing the within-plot variability and characterizing the immediate physiological responses of the crop to the modified microclimate, providing a robust baseline for understanding APV-crop interactions.

Second, although the experiment encompassed distinct wet and dry seasons, the data represent a single-year cycle. Given the inter-annual variability of tropical weather patterns—particularly regarding rainfall distribution and El Niño-Southern Oscillation events—continuous monitoring is essential to confirm the long-term stability of the observed yield advantages.

In addition, the fixed APV structure used in this study did not include a rainwater collection or redistribution system. During the dry-season cultivation, when rainfall events were concentrated into a limited number of high-intensity events, localized lodging of soybean plants was observed beneath the panel edges due to concentrated water discharge. To mitigate this effect, additional plant supports were installed during the cultivation period, which reduced further lodging and allowed normal crop development to continue. Although this management intervention limited its influence on final yield, the observation highlights a practical limitation of fixed agrivoltaic systems under tropical rainfall conditions and underscores the need for site-specific drainage design and structural mitigation strategies.

Therefore, future research should aim to extend these findings through multi-site, multi-year trials employing RCBD across diverse agro-ecological zones. Such expanded studies would allow for a comprehensive assessment of the interactions between APV shading, soil types, and regional microclimates, ultimately supporting the development of standardized guidelines for scaling up agrivoltaic systems in Indonesia and the broader tropical region.

5. Conclusions

This study quantitatively evaluated the effects of an APV system on the microclimate, growth, and yield of soybean (Glycine max) across wet and dry seasons in the tropical monsoon climate of Bogor, Indonesia. The results demonstrated that the about 35% reduction in solar radiation by the APV structure did not hinder crop growth but rather induced positive microclimatic modifications by mitigating excessive radiative loads and moderating soil temperatures, while effectively conserving soil moisture.

These environmental benefits translated into distinct yield advantages in both seasons. In the wet season, the APV system shielded the crop from intense solar radiation and soil heating, maximizing pod formation and resulting in a remarkable 106% yield increase compared to the open field. In the dry season, the superior moisture conservation under APV alleviated physiological water stress and improved assimilate partitioning (HI), leading to a 17% yield gain. Furthermore, phenological development (R1–R5) was not delayed under APV conditions, and vegetative growth was maintained or enhanced, confirming that the reduced light levels remained sufficient for soybean physiological processes.

In conclusion, this study validates that in tropical climates, APV systems serve not merely as a dual land-use strategy but as an effective climate adaptation technology that protects crops from intensifying environmental stresses. These findings suggest that APV offers a sustainable solution for equatorial nations like Indonesia to achieve renewable energy targets without compromising—and potentially enhancing—food security. Future research should address the economic feasibility of such systems, alongside long-term assessments of soil fertility dynamics and genotype-specific adaptability under varying meteorological conditions.