Genome-Wide Analysis of the GH3 Gene Family in Nicotiana benthamiana and Its Role in Plant Defense Against Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. GH3 Gene Family Identification in N. benthamiana

2.2. Phylogenetic Tree Generation and Conserved Motif Identification of NbGH3 Proteins

2.3. Gene Structure Analysis and Promoter cis-Acting Element Prediction of NbGH3 Genes

2.4. Chromosomal Localization and Collinearity Analysis of NbGH3 Genes

2.5. Tissue-Specific Expression Pattern Analysis of NbGH3 Genes

2.6. Plant Materials and YLCV Infectious Clone Construction and Inoculation

2.7. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Vector Construction and Experiment

2.8. RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

2.9. DNA Extraction and Viral Accumulation Measurement

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of the GH3 Gene Family in N. benthamiana

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of NbGH3 Proteins in N. benthamiana

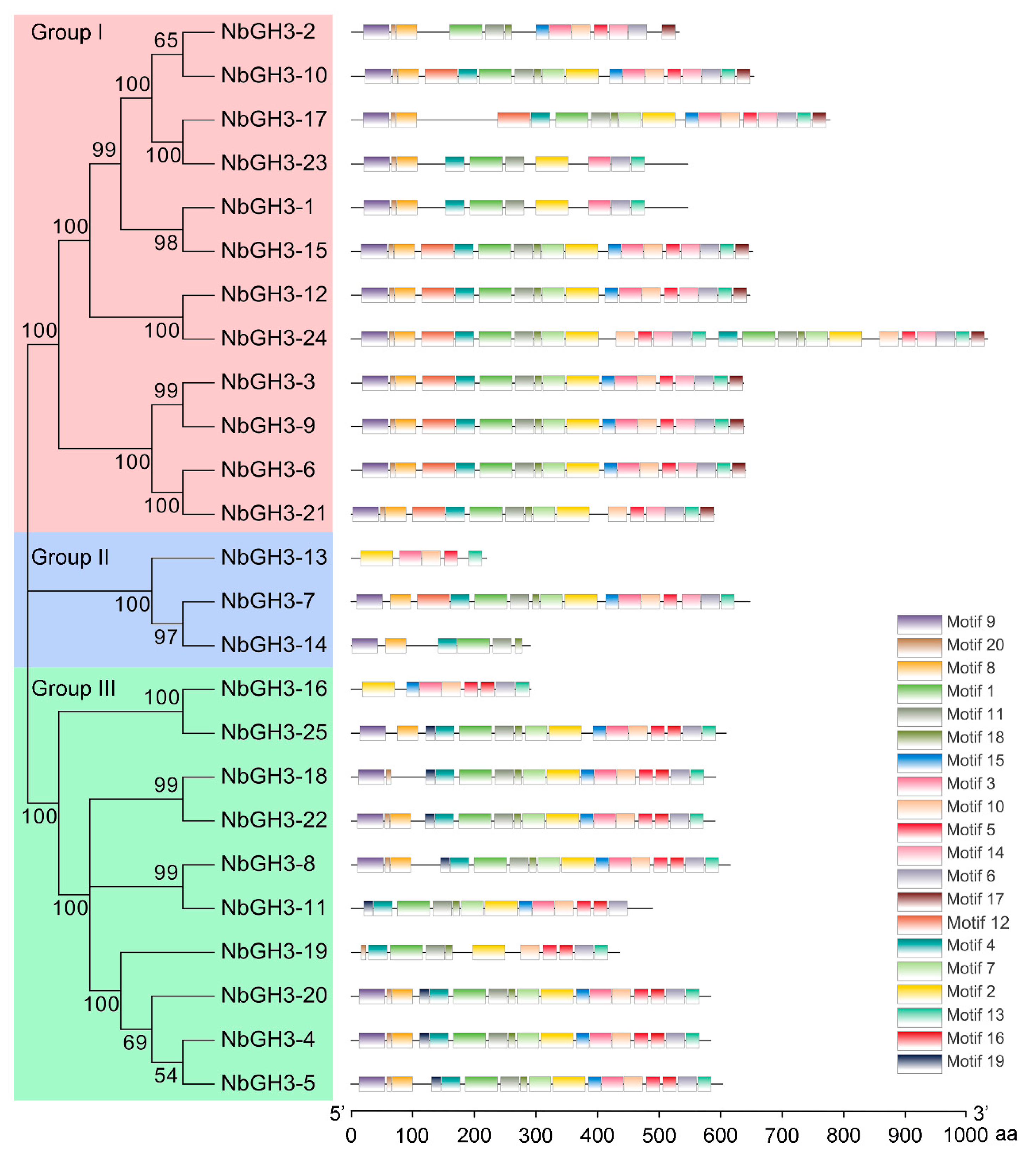

3.3. Conserved Motif Analysis of NbGH3 Proteins

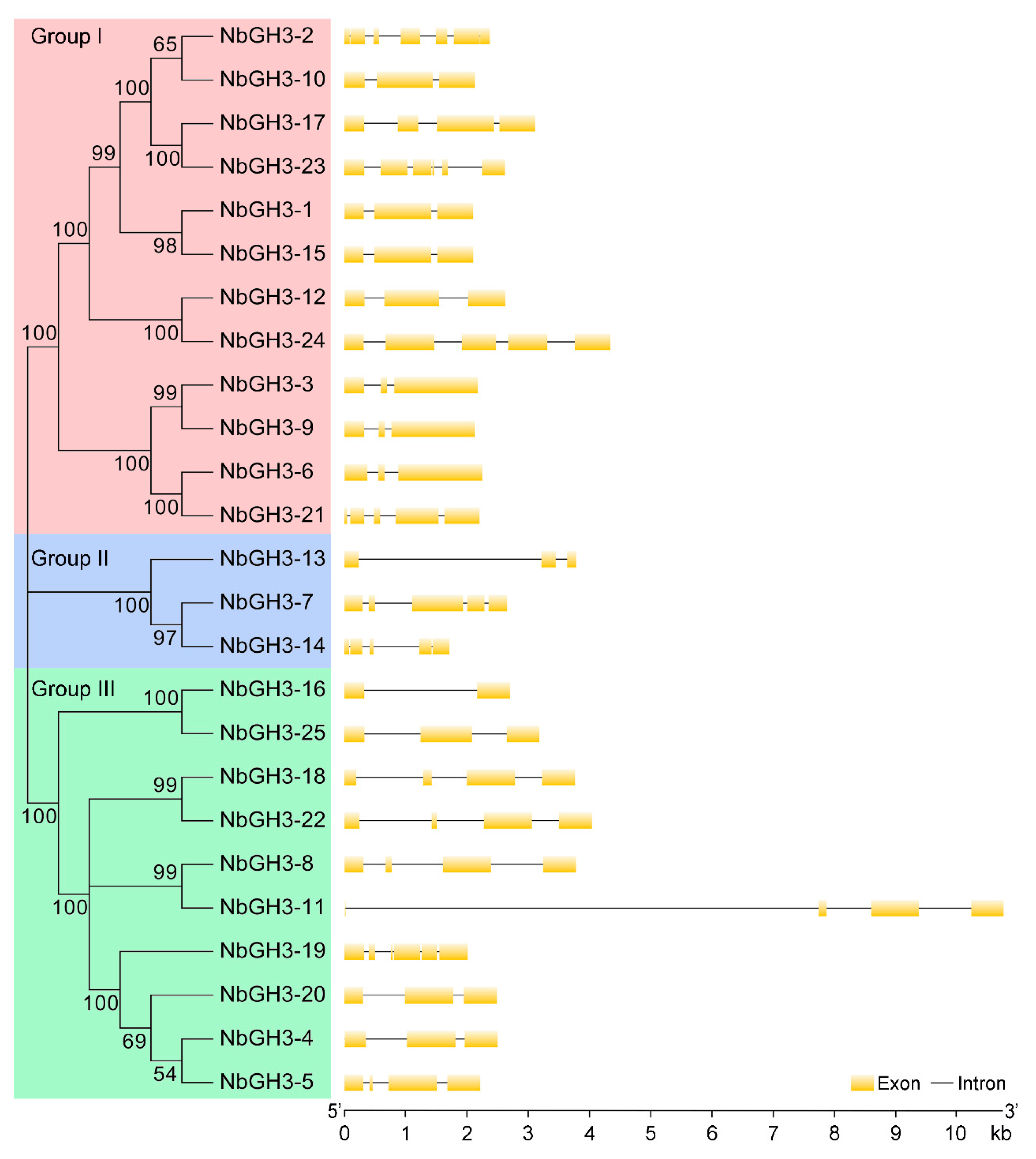

3.4. Gene Structure Analysis of NbGH3 Genes

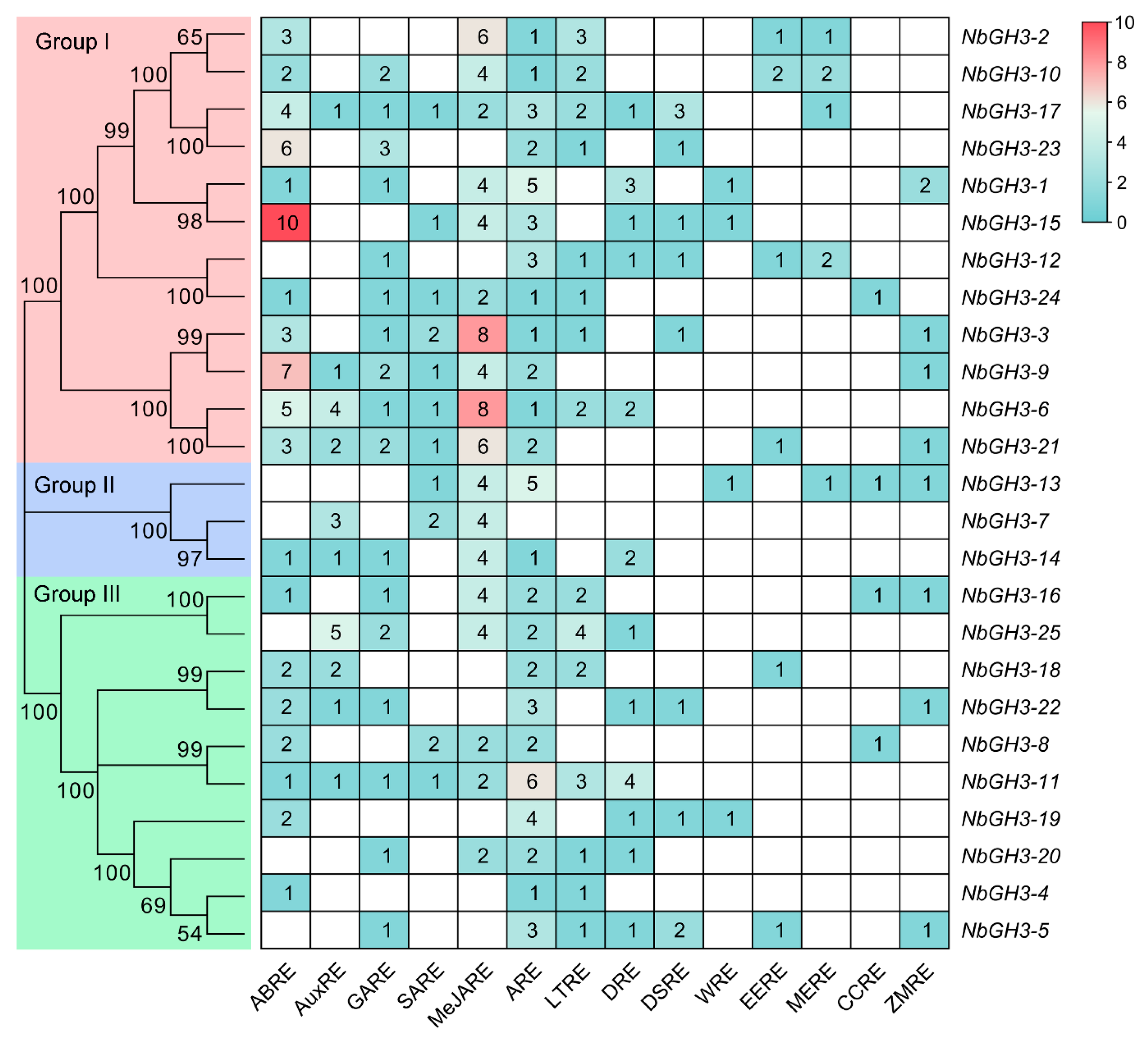

3.5. Promoter Analysis of NbGH3 Genes

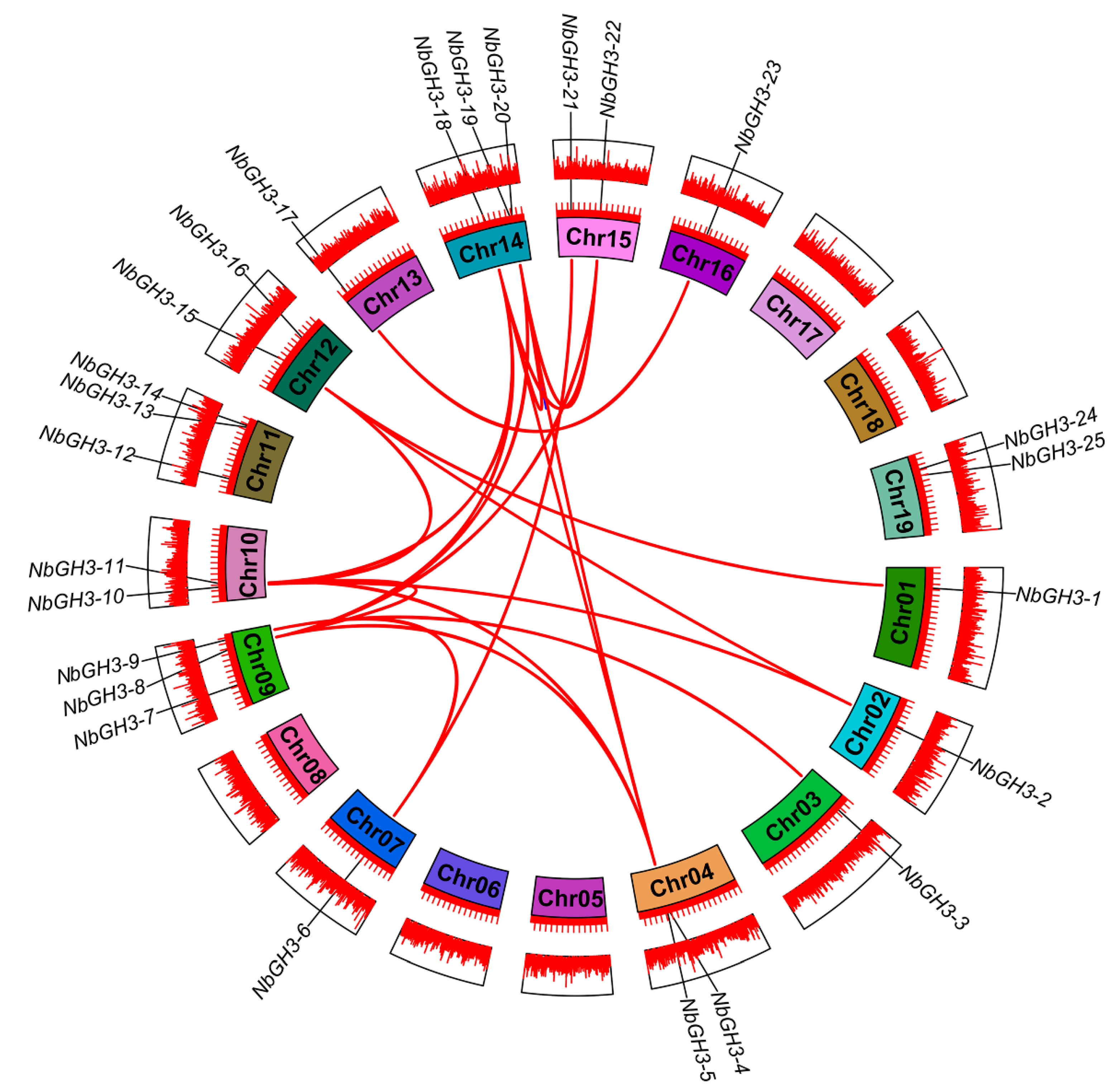

3.6. Chromosomal Location and Synteny Analyses of NbGH3 Genes

3.7. Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of NbGH3 Genes

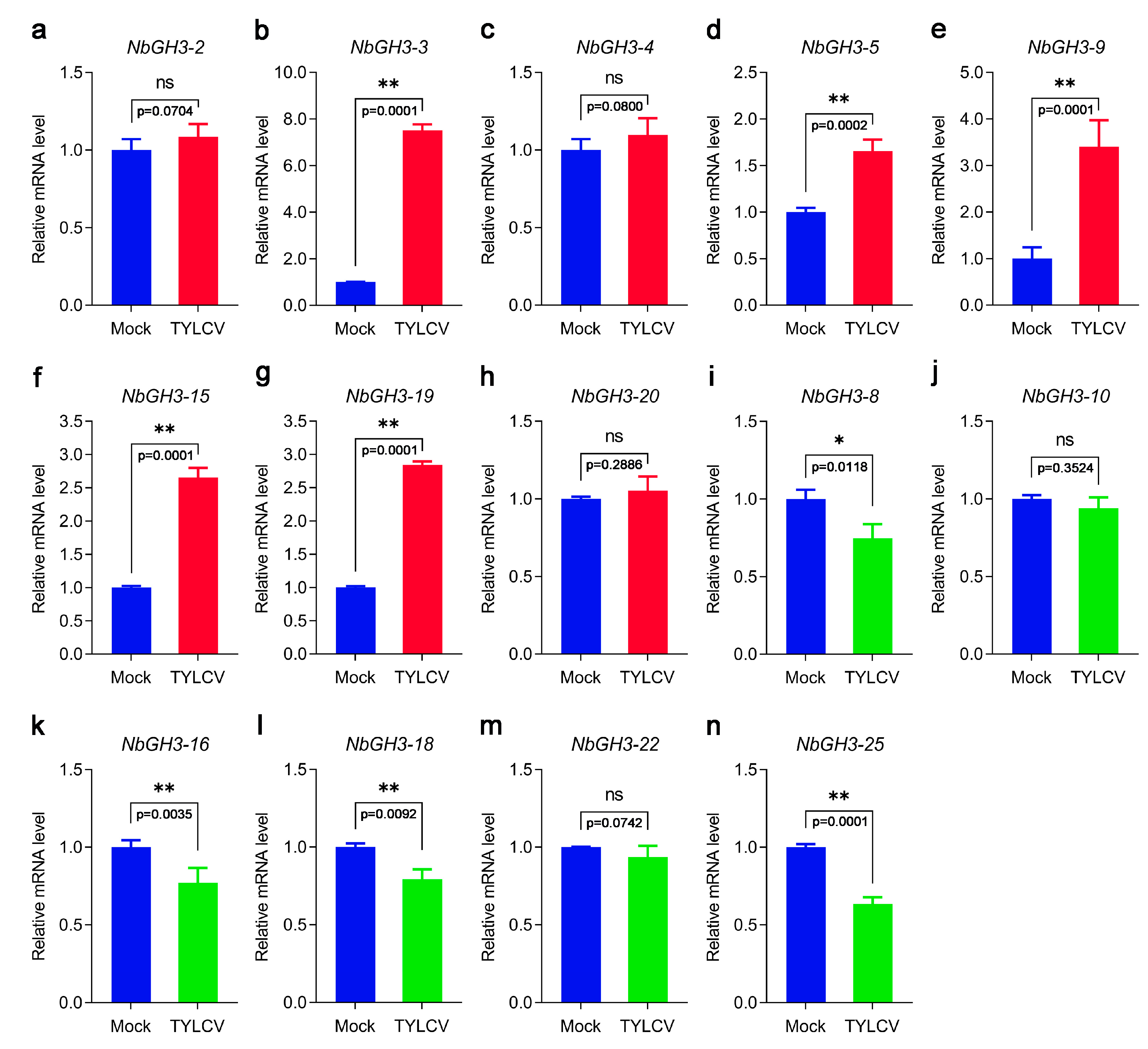

3.8. Expression Profiles of NbGH3 Genes Following TYLCV Infection

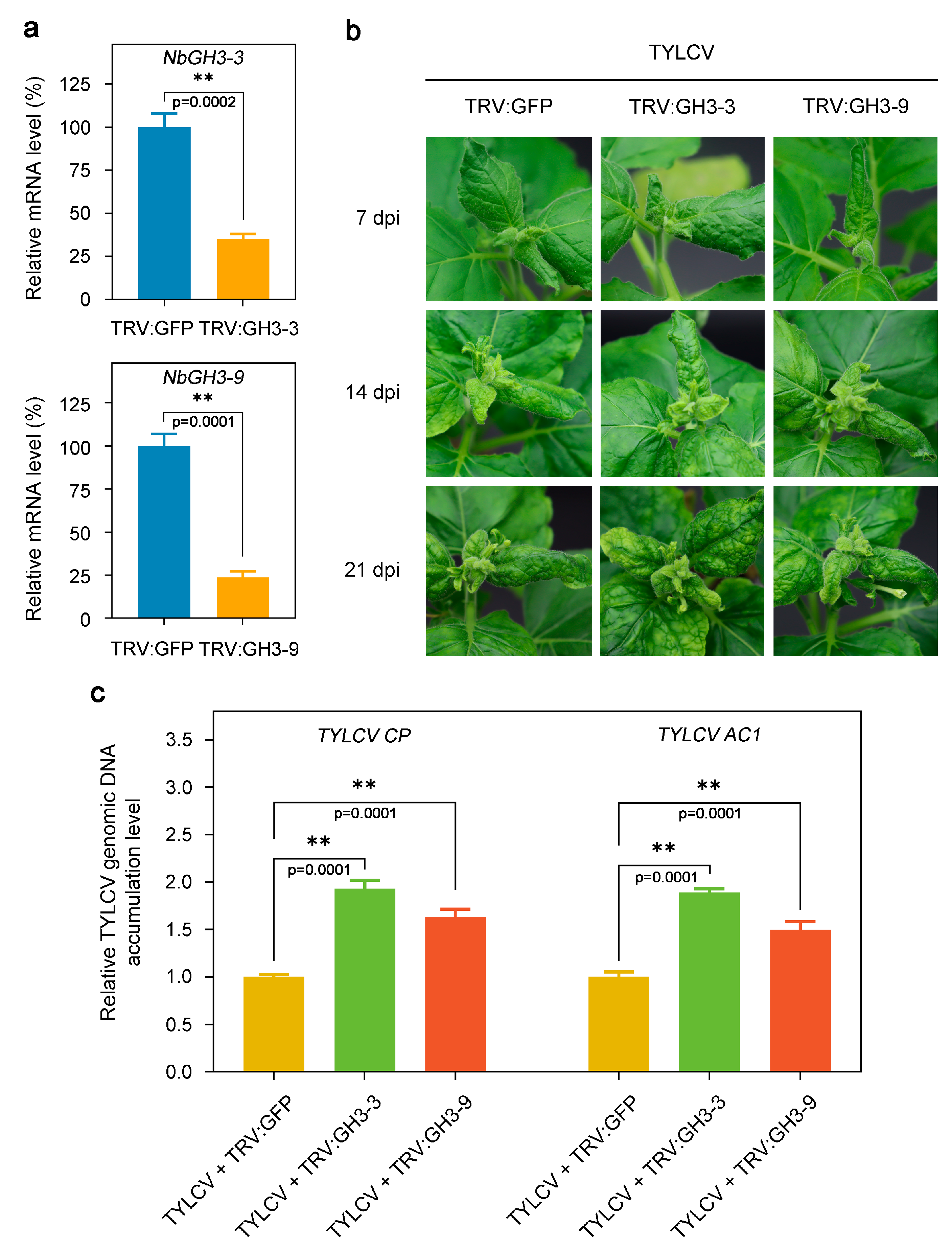

3.9. Disruption of the Expression of NbGH3-3 and NbGH3-9 Enhances Host Susceptibility to TYLCV

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gomes, G.L.B.; Scortecci, K.C. Auxin and its role in plant development: Structure, signalling, regulation and response mechanisms. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, H.; Wilkinson, E.G.; Sageman-Furnas, K.; Strader, L.C. Auxin and abiotic stress responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 7000–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Zhou, J.J.; Zhang, J.Z. Aux/IAA gene family in plants: Molecular structure, regulation, and function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhong, K.; Li, Y.; Bai, C.; Xue, Z.; Wu, Y. Evolutionary analysis of the melon (Cucumis melo L.) GH3 gene family and identification of GH3 genes related to fruit growth and development. Plants 2023, 12, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.; Chang, S.; Li, X.; Qi, Y. Advances in the study of auxin early response genes: Aux/IAA, GH3, and SAUR. Crop J. 2024, 12, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yue, R.; Sun, T.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Zeng, H.; Wang, H.; Shen, C. Genome-wide identification, expression analysis of GH3 family genes in Medicago truncatula under stress-related hormones and Sinorhizobium meliloti infection. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Yin, J.; Zhang, H.; He, Y.; Shuai, S.; Chen, S.; Cao, S.; Li, W.; Ma, D.; Chen, H. Genome-wide identification, characterization analysis and expression profiling of auxin-responsive GH3 family genes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 3885–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Lin, P.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, D.; Qin, L.; Xu, F.; Su, Y.; Wu, Q.; Que, Y. Genome-wide identification of auxin-responsive GH3 gene family in Saccharum and the expression of ScGH3-1 in stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle, T.J. Rapid induction of selective transcription by auxins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985, 5, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, C.; Perrot-Rechenmann, C. Isolation by differential display and characterization of a tobacco auxin-responsive cDNA Nt-gh3, related to GH3. FEBS Lett. 1997, 419, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staswick, P.E.; Serban, B.; Rowe, M.; Tiryaki, I.; Maldonado, M.T.; Maldonado, M.C.; Suza, W. Characterization of an Arabidopsis enzyme family that conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.; Kaur, N.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. The auxin-responsive GH3 gene family in rice (Oryza sativa). Funct. Integr. Genom. 2006, 6, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Zhao, K.; Lei, H.; Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liao, X.; Li, T. Genome-wide analysis of the GH3 family in apple (Malus × domestica). BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Jain, M.; Garg, R. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling suggest diverse roles of GH3 genes during development and abiotic stress responses in legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Yue, R.; Tao, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Shen, C. Genome-wide identification, expression analysis of auxin-responsive GH3 family genes in maize (Zea mays L.) under abiotic stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015, 57, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Chen, X.; Chen, A.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Gu, M.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. The characterization of six auxin-induced tomato GH3 genes uncovers a member, SlGH3.4, strongly responsive to arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Yang, B.; Jian, H.; Zhang, A.; Liu, R.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, J.; Shi, X.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of Gretchen Hagen 3 (GH3) family genes in Brassica napus. Genome 2019, 62, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Zhang, C.; Qin, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xie, X.; Bai, J.; Sun, C.; Bi, Z. Comprehensive analysis of GH3 gene family in potato and functional characterization of StGH3.3 under drought stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamat, U.; Awan, M.J.A.; Ahmad, M.; Farooq, M.A. Genomic analysis and expression dynamics of GH3 genes under abiotic stresses in Brassica rapa. Plant Breed. 2024, 144, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, C.; An, L.; Zeng, J.; Ren, A.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S. Genome-wide identification and expression characterization of the GH3 gene family of tea plant (Camellia sinensis). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.; Hao, M.; Liu, H.; Xiao, J.; Li, X.; Yuan, M.; Wang, S. The group I GH3 family genes encoding JA-Ile synthetase act as positive regulator in the resistance of rice to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 508, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtaczka, P.; Ciarkowska, A.; Starzynska, E.; Ostrowski, M. The GH3 amidosynthetases family and their role in metabolic crosstalk modulation of plant signaling compounds. Phytochemistry 2022, 194, 113039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jez, J.M. Connecting primary and specialized metabolism: Amino acid conjugation of phytohormones by GRETCHEN HAGEN 3 (GH3) acyl acid amido synthetases. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 66, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Min, X.; Luo, K.; Hamidou Abdoulaye, A.; Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y. Molecular characterization of the GH3 family in alfalfa under abiotic stress. Gene 2023, 851, 146982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wu, N.; Fu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, L. A GH3 family member, OsGH3-2, modulates auxin and abscisic acid levels and differentially affects drought and cold tolerance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 6467–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirungu, J.N.; Magwanga, R.O.; Lu, P.; Cai, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Peng, R.; Wang, K.; Liu, F. Functional characterization of Gh_A08G1120 (GH3.5) gene reveal their significant role in enhancing drought and salt stress tolerance in cotton. BMC Genet. 2019, 20, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Sáez, R.; Mateo-Bonmatí, E.; Šimura, J.; Pěnčík, A.; Novák, O.; Staswick, P.; Ljung, K. Inactivation of the entire Arabidopsis group II GH3s confers tolerance to salinity and water deficit. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Cao, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhao, J.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Activation of the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3-8 suppresses expansin expression and promotes salicylate- and jasmonate-independent basal immunity in rice. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S. Manipulating broad-spectrum disease resistance by suppressing pathogen-induced auxin accumulation in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; He, Y.; Xu, L.; Peng, A.; Lei, T.; Yao, L.; Li, Q.; Zhou, P.; Bai, X.; Duan, M.; et al. Cloning and expression analysis of citrus genes CsGH3.1 and CsGH3.6 responding to Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri infection. Hortic. Plant J. 2016, 2, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Long, J.; Zhao, K.; Peng, A.; Chen, M.; Long, Q.; He, Y.; Chen, S. Overexpressing GH3.1 and GH3.1L reduces susceptibility to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri by repressing auxin signaling in citrus (Citrus sinensis Osbeck). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Xian, B.; Fan, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, W.; Zou, X.; Chen, S.; Su, L.; et al. CsAP2-09 confers resistance against citrus bacterial canker by regulating CsGH3.1L-mediated phytohormone biosynthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 229, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Datta, T.; Wei, F.; Xie, Z. Polyploidization: A biological force that enhances stress resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Feng, C.; Wu, K.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; Hao, X.; Wu, Y. Advances and prospects in biogenic substances against plant virus: A review. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 135, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A.C. Global plant virus disease pandemics and epidemics. Plants 2021, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, M.E.; Tadić, V.; Popović, M. (R)evolution of Viruses: Introduction to biothermodynamics of viruses. Virology 2024, 603, 110319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Lett, J.M.; Martin, D.P.; Roumagnac, P.; Varsani, A.; Zerbini, F.M.; Navas-Castillo, J. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Geminiviridae 2021. J. Gen. Virol. 2021, 102, 001696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Qiao, R.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhou, X. Occurrence and distribution of geminiviruses in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 1498–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Navas-Castillo, J. Begomoviruses: What is the secret(s) of their success? Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Al Hashash, H.; Al-Ali, E. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) in Kuwait and global analysis of the population structure and evolutionary pattern of TYLCV. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Sharma, N.; Hari-Gowthem, G.; Muthamilarasan, M.; Prasad, M. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus: Impact, challenges, and management. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Qiao, R.; Yang, X.; Gong, P.; Zhou, X. Occurrence, distribution, and management of tomato yellow leaf curl virus in China. Phytopathol. Res. 2022, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Chang, Z.; Li, F.; Zhou, X. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus V3 protein traffics along microfilaments to plasmodesmata to promote virus cell-to-cell movement. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 1046–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Chang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Gong, P.; Zhang, M.; Lozano-Durán, R.; Yan, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. Functional identification of a novel C7 protein of tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Virology 2023, 585, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yu, S.; Ye, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Shi, M.; Zhao, G.; Shen, Y.; Lu, Z.; Yu, Z.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the HECT-type E3 ubiquitin ligase gene family in Nicotiana benthamiana: Evidence implicating NbHECT6 and NbHECT13 in the response to tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection. Genes 2025, 16, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sappah, A.H.; Qi, S.; Soaud, S.A.; Huang, Q.; Saleh, A.M.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Wan, L.; Cheng, G.T.; Liu, J.; Ihtisham, M.; et al. Natural resistance of tomato plants to tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1081549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S.; Souvan, J.M.; Bally, J.; de Felippes, F.F.; Waterhouse, P.M. Exploring the source of TYLCV resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1404160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombarely, A.; Rosli, H.G.; Vrebalov, J.; Moffett, P.; Mueller, L.A.; Martin, G.B. A draft genome sequence of Nicotiana benthamiana to enhance molecular plant-microbe biology research. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvaud, S.; Gabella, C.; Lisacek, F.; Stockinger, H.; Ioannidis, V.; Durinx, C. Expasy, the Swiss Bioinformatics Resource Portal, as designed by its users. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W216–W227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.; Xu, H.; Hu, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of wall-associated kinase (WAK) and WAK-like kinase gene family in response to tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection in Nicotiana benthamiana. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Joseph, P.V.; Paterson, A.H. Detection of colinear blocks and synteny and evolutionary analyses based on utilization of MCScanX. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 2206–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bally, J.; Nakasugi, K.; Jia, F.; Jung, H.; Ho, S.Y.; Wong, M.; Paul, C.M.; Naim, F.; Wood, C.C.; Crowhurst, R.N.; et al. The extremophile Nicotiana benthamiana has traded viral defence for early vigour. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranawaka, B.; An, J.; Lorenc, M.T.; Jung, H.; Sulli, M.; Aprea, G.; Roden, S.; Llaca, V.; Hayashi, S.; Asadyar, L.; et al. A multi-omic Nicotiana benthamiana resource for fundamental research and biotechnology. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasugi, K.; Crowhurst, R.N.; Bally, J.; Wood, C.C.; Hellens, R.P.; Waterhouse, P.M. De novo transcriptome sequence assembly and analysis of RNA silencing genes of Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lu, J.; Aiwaili, P.; Fei, Z.; Jiang, C.Z.; Hong, B.; Ma, C.; et al. Auxin regulates sucrose transport to repress petal abscission in rose (Rosa hybrida). Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3485–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Wang, Z.Q.; Xiao, R.; Cao, L.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, X. Mimic phosphorylation of a βC1 protein encoded by TYLCCNB impairs its functions as a viral suppressor of RNA silencing and a symptom determinant. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00300-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Wang, Z.Q.; Liu, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Xie, Y. Identification and analysis of potential genes regulated by an alphasatellite (TYLCCNA) that contribute to host resistance against tomato yellow leaf curl China virus and its betasatellite (TYLCCNV/TYLCCNB) infection in Nicotiana benthamiana. Viruses 2019, 11, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Xie, Y.; Tao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Fauquet, C.M. Characterization of DNAbeta associated with begomoviruses in China and evidence for co-evolution with their cognate viral DNA-A. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Schiff, M.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. Virus-induced gene silencing in tomato. Plant J. 2002, 31, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil-Kumar, M.; Mysore, K.S. Tobacco rattle virus-based virus-induced gene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Wang, Z.Q.; Xiao, R.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, X. iTRAQ analysis of the tobacco leaf proteome reveals that RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) has important roles in defense against geminivirus-betasatellite infection. J. Proteom. 2017, 152, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Liu, C.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, X. Geminiviruses employ host DNA glycosylases to subvert DNA methylation-mediated defense. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Tang, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Integrated next-generation sequencing and comparative transcriptomic analysis of leaves provides novel insights into the ethylene pathway of Chrysanthemum morifolium in response to a Chinese isolate of chrysanthemum virus B. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Redfern, O.; Orengo, C. Predicting protein function from sequence and structure. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, R.; Hussain, A.; Tariq, A.; Khalid, M.H.B.; Khan, I.; Basim, H.; Ingvarsson, P.K. Genome-wide analyses of the mung bean NAC gene family reveals orthologs, co-expression networking and expression profiling under abiotic and biotic stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, P.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B.; et al. Identification of TALE transcription factor family and expression patterns related to fruit chloroplast development in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, A.; Jimenez, J.; Pérez-Pulido, A.J. Assessment of selection pressure exerted on genes from complete pangenomes helps to improve the accuracy in the prediction of new genes. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analysis suggests the evolutionary dynamic of GH3 genes in Gramineae crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Shen, D.; Wang, J.; Ling, X.; Hu, Z.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; Huang, J.; Yu, W.; et al. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus intergenic siRNAs target a host long noncoding RNA to modulate disease symptoms. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, C.S.; Zubieta, C.; Herrmann, J.; Kapp, U.; Nanao, M.H.; Jez, J.M. Structural basis for prereceptor modulation of plant hormones by GH3 proteins. Science 2012, 336, 1708–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Zhong, H.; Deng, X.; Gautam, M.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Evolutionary analysis of GH3 genes in six Oryza species/subspecies and their expression under salinity stress in Oryza sativa ssp. japonica. Plants 2019, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Qanmber, G.; Lu, L.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Mendu, V.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of cotton GH3 subfamily II reveals functional divergence in fiber development, hormone response and plant architecture. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Duan, P.; Zhang, H.; Lu, X.; Shi, Z.; Cui, J. Genome-wide identification of CmaGH3 family genes, and expression analysis in response to cold and hormonal stresses in Cucurbita maxima. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wan, S.; Zhou, J.; Shao, Q.S.; Xing, B. Transcriptional regulation of plant seed development. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 2013–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.H. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ri, H.C.; An, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.N.; Zheng, D.; Wu, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, J.; et al. Deletion and tandem duplications of biosynthetic genes drive the diversity of triterpenoids in Aralia elata. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, G.; Huang, R.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Li, G.; Li, W.; Ahiakpa, J.K.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, J. SlGH3.15, a member of the GH3 gene family, regulates lateral root development and gravitropism response by modulating auxin homeostasis in tomato. Plant Sci. 2023, 330, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Gene ID | Gene Position | Size | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA (bp) | Number of Exons | CDS a (bp) | Protein (aa) | pI b | MW c (kDa) | |||

| NbGH3-1 | Niben261Chr01g0372004 | Niben261Chr01:37226808–37228912 | 2105 | 3 | 1830 | 609 | 6.14 | 68.83 |

| NbGH3-2 | Niben261Chr02g0532025 | Niben261Chr02:53138133–53140510 | 2378 | 7 | 1494 | 497 | 5.17 | 56.64 |

| NbGH3-3 | Niben261Chr03g0253011 | Niben261Chr03:25293847–25296028 | 2182 | 3 | 1788 | 595 | 6.15 | 67.80 |

| NbGH3-4 | Niben261Chr04g1362002 | Niben261Chr04:136228641–136231149 | 2509 | 3 | 1641 | 546 | 5.87 | 61.06 |

| NbGH3-5 | Niben261Chr04g1363001 | Niben261Chr04:136304348–136306576 | 2229 | 4 | 1695 | 564 | 6.35 | 63.23 |

| NbGH3-6 | Niben261Chr07g0596001 | Niben261Chr07:59590185–59592441 | 2257 | 3 | 1800 | 599 | 5.51 | 67.44 |

| NbGH3-7 | Niben261Chr09g0422008 | Niben261Chr09:42257839–42260500 | 2662 | 5 | 1818 | 605 | 6.19 | 68.47 |

| NbGH3-8 | Niben261Chr09g1105009 | Niben261Chr09:110495691–110499486 | 3796 | 4 | 1728 | 575 | 5.97 | 63.90 |

| NbGH3-9 | Niben261Chr09g1267004 | Niben261Chr09:126721282–126723417 | 2136 | 3 | 1791 | 596 | 6.41 | 67.68 |

| NbGH3-10 | Niben261Chr10g0264011 | Niben261Chr10:26452362–26454501 | 2140 | 3 | 1836 | 611 | 5.87 | 68.64 |

| NbGH3-11 | Niben261Chr10g0296001 | Niben261Chr10:29601688–29612588 | 10,901 | 3 | 1374 | 457 | 6.83 | 50.82 |

| NbGH3-12 | Niben261Chr11g0267003 | Niben261Chr11:26739665–26742295 | 2631 | 3 | 1818 | 605 | 5.34 | 68.50 |

| NbGH3-13 | Niben261Chr11g1285005 | Niben261Chr11:128515781–128519576 | 3796 | 3 | 618 | 205 | 5.95 | 23.40 |

| NbGH3-14 | Niben261Chr11g1285006 | Niben261Chr11:128519615–128521336 | 1722 | 5 | 819 | 272 | 6.63 | 30.69 |

| NbGH3-15 | Niben261Chr12g0633003 | Niben261Chr12:63330097–63332206 | 2110 | 3 | 1830 | 609 | 6.09 | 68.77 |

| NbGH3-16 | Niben261Chr12g1113006 | Niben261Chr12:111292646–111295357 | 2712 | 2 | 864 | 287 | 7.00 | 32.35 |

| NbGH3-17 | Niben261Chr13g0109001 | Niben261Chr13:10889450–10892574 | 3125 | 4 | 2181 | 726 | 6.31 | 82.12 |

| NbGH3-18 | Niben261Chr14g0843004 | Niben261Chr14:84299555–84303331 | 3777 | 4 | 1662 | 553 | 5.21 | 62.12 |

| NbGH3-19 | Niben261Chr14g1298001 | Niben261Chr14:129816379–129818398 | 2020 | 6 | 1224 | 407 | 6.52 | 45.26 |

| NbGH3-20 | Niben261Chr14g1298003 | Niben261Chr14:129840681–129843179 | 2499 | 3 | 1641 | 546 | 6.18 | 60.95 |

| NbGH3-21 | Niben261Chr15g0259008 | Niben261Chr15:25898600–25900811 | 2212 | 5 | 1656 | 551 | 7.02 | 62.20 |

| NbGH3-22 | Niben261Chr15g0793008 | Niben261Chr15:79266683–79270736 | 4054 | 4 | 1659 | 552 | 5.52 | 62.09 |

| NbGH3-23 | Niben261Chr16g0650005 | Niben261Chr16:65078196–65080827 | 2632 | 6 | 1560 | 519 | 8.74 | 59.10 |

| NbGH3-24 | Niben261Chr19g0285009 | Niben261Chr19:28555936–28560293 | 4358 | 5 | 2901 | 966 | 6.82 | 109.01 |

| NbGH3-25 | Niben261Chr19g0376004 | Niben261Chr19:37672806–37676002 | 3197 | 3 | 1710 | 569 | 5.81 | 64.85 |

| Gene Pairs | Duplicate Type | Ka a | Ks b | Ka/Ks | Duplication Date (MY c) | Purifying Selection d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NbGH3-1 | NbGH3-15 | Segmental | 0.008 | 0.093 | 0.084 | 11.94 | Yes |

| NbGH3-2 | NbGH3-10 | Segmental | 0.112 | 0.380 | 0.295 | 48.66 | Yes |

| NbGH3-2 | NbGH3-15 | Segmental | 0.129 | 0.740 | 0.174 | 94.76 | Yes |

| NbGH3-3 | NbGH3-9 | Segmental | 0.016 | 0.119 | 0.132 | 15.28 | Yes |

| NbGH3-4 | NbGH3-8 | Segmental | 0.088 | 0.738 | 0.119 | 94.46 | Yes |

| NbGH3-4 | NbGH3-19 | Segmental | 0.065 | 0.175 | 0.372 | 22.36 | Yes |

| NbGH3-5 | NbGH3-11 | Segmental | 0.139 | 0.938 | 0.148 | 120.05 | Yes |

| NbGH3-5 | NbGH3-18 | Segmental | 0.104 | 0.945 | 0.110 | 120.93 | Yes |

| NbGH3-6 | NbGH3-9 | Segmental | 0.139 | 1.883 | 0.074 | 241.01 | Yes |

| NbGH3-6 | NbGH3-21 | Segmental | 0.030 | 0.227 | 0.134 | 29.08 | Yes |

| NbGH3-8 | NbGH3-11 | Segmental | 0.061 | 0.243 | 0.253 | 31.08 | Yes |

| NbGH3-8 | NbGH3-18 | Segmental | 0.085 | 0.895 | 0.095 | 114.61 | Yes |

| NbGH3-8 | NbGH3-19 | Segmental | 0.107 | 0.695 | 0.154 | 89.00 | Yes |

| NbGH3-8 | NbGH3-22 | Segmental | 0.073 | 0.840 | 0.087 | 107.51 | Yes |

| NbGH3-10 | NbGH3-15 | Segmental | 0.106 | 0.759 | 0.139 | 97.18 | Yes |

| NbGH3-11 | NbGH3-18 | Segmental | 0.125 | 0.902 | 0.138 | 115.44 | Yes |

| NbGH3-17 | NbGH3-23 | Segmental | 0.132 | 0.302 | 0.437 | 38.59 | Yes |

| NbGH3-18 | NbGH3-20 | Segmental | 0.126 | 1.001 | 0.126 | 128.10 | Yes |

| NbGH3-18 | NbGH3-22 | Segmental | 0.040 | 0.190 | 0.211 | 24.30 | Yes |

| NbGH3-20 | NbGH3-22 | Segmental | 0.103 | 0.975 | 0.105 | 124.80 | Yes |

| NbGH3-19 | NbGH3-20 | Tandem | 0.056 | 0.085 | 0.666 | 108.34 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhong, X.; Fang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Z. Genome-Wide Analysis of the GH3 Gene Family in Nicotiana benthamiana and Its Role in Plant Defense Against Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. Agronomy 2026, 16, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010115

Zhong X, Fang X, Sun Y, Zeng Y, Yu Z, Li J, Wang Z. Genome-Wide Analysis of the GH3 Gene Family in Nicotiana benthamiana and Its Role in Plant Defense Against Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Xueting, Xiuyan Fang, Yuan Sun, Ye Zeng, Zaihang Yu, Jiapeng Li, and Zhanqi Wang. 2026. "Genome-Wide Analysis of the GH3 Gene Family in Nicotiana benthamiana and Its Role in Plant Defense Against Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010115

APA StyleZhong, X., Fang, X., Sun, Y., Zeng, Y., Yu, Z., Li, J., & Wang, Z. (2026). Genome-Wide Analysis of the GH3 Gene Family in Nicotiana benthamiana and Its Role in Plant Defense Against Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. Agronomy, 16(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010115