Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Mitigate Crop Multi-Stresses Under Mediterranean Climate: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

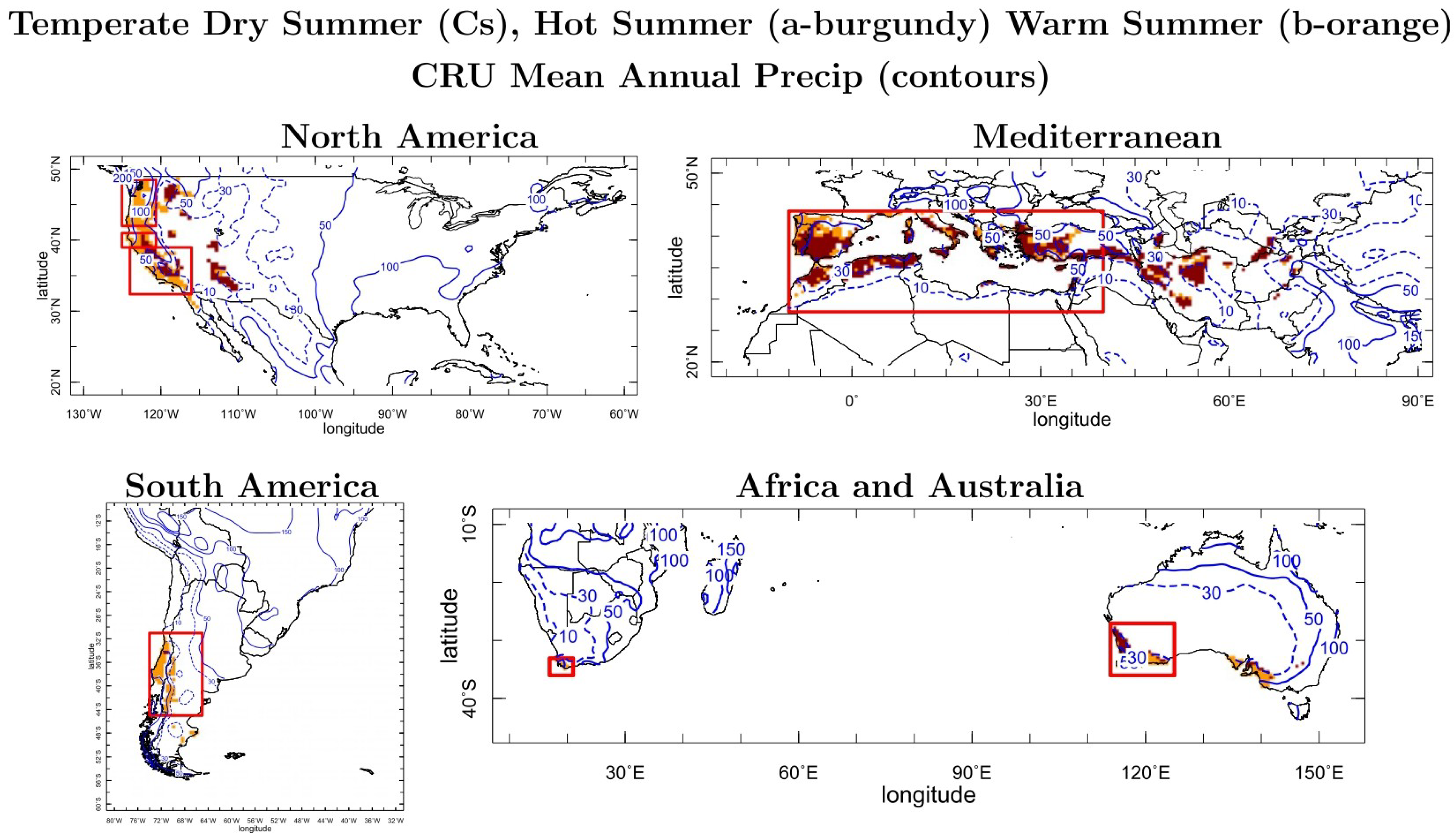

Agricultural Systems Under Mediterranean-Type Climates

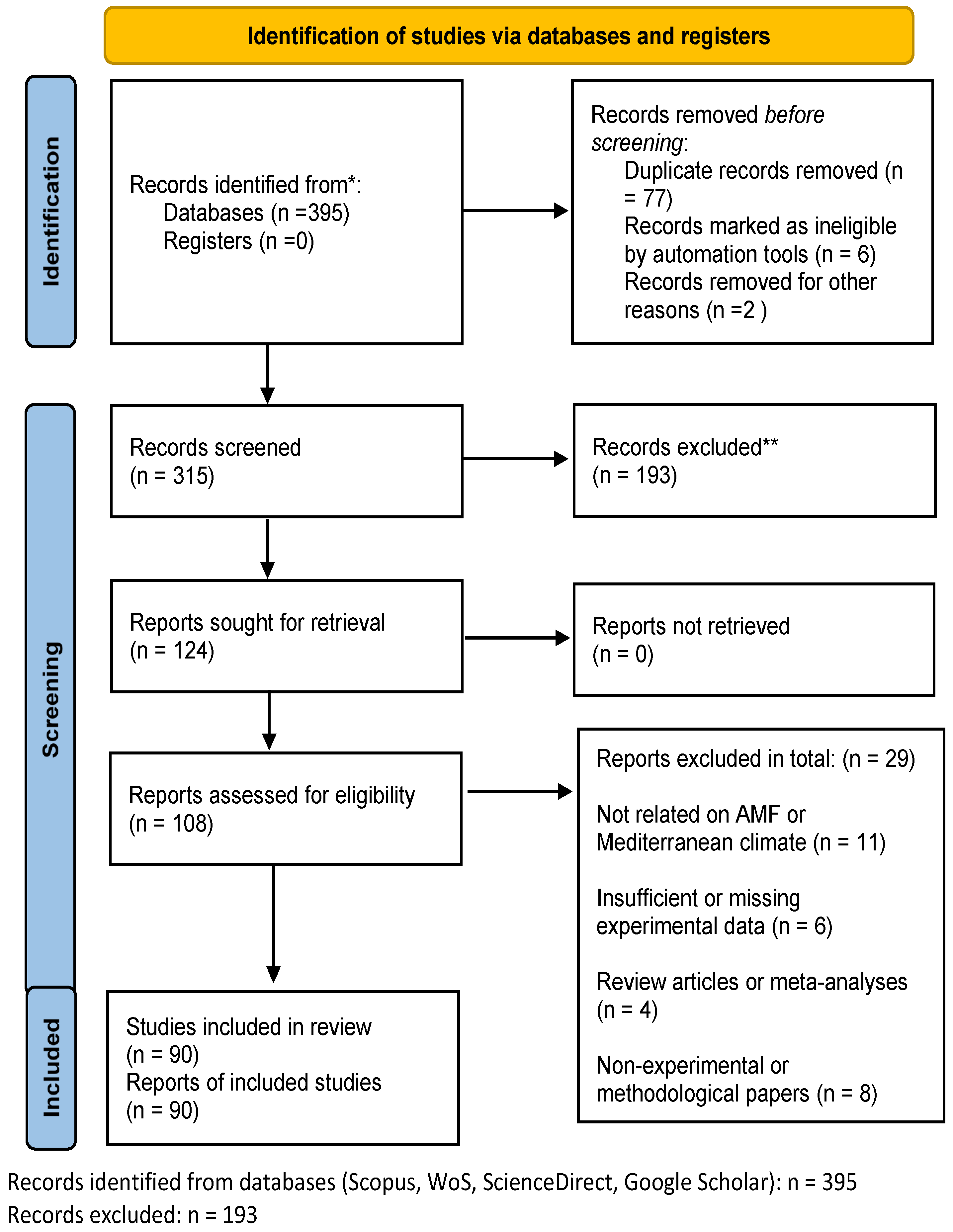

2. Materials and Methods

- Articles published in English in peer-reviewed journals;

- Studies evaluating the effect of AMF on crops exposed to abiotic or biotic stress, with explicit focus on Mediterranean climates or comparable environments;

- Research reporting quantitative or qualitative data on agronomic performance, physiological responses, nutritional parameters, or microbe–plant interactions associated with AMF.

- Conference abstracts, book chapters, editorials, and non-peer-reviewed material;

- Studies not dealing with AMF in agricultural contexts;

- Articles lacking sufficient methodological detail or presenting unquantified or inconclusive outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Abiotic Stress and Its Mitigation Through Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi

3.1.1. Drought Stress

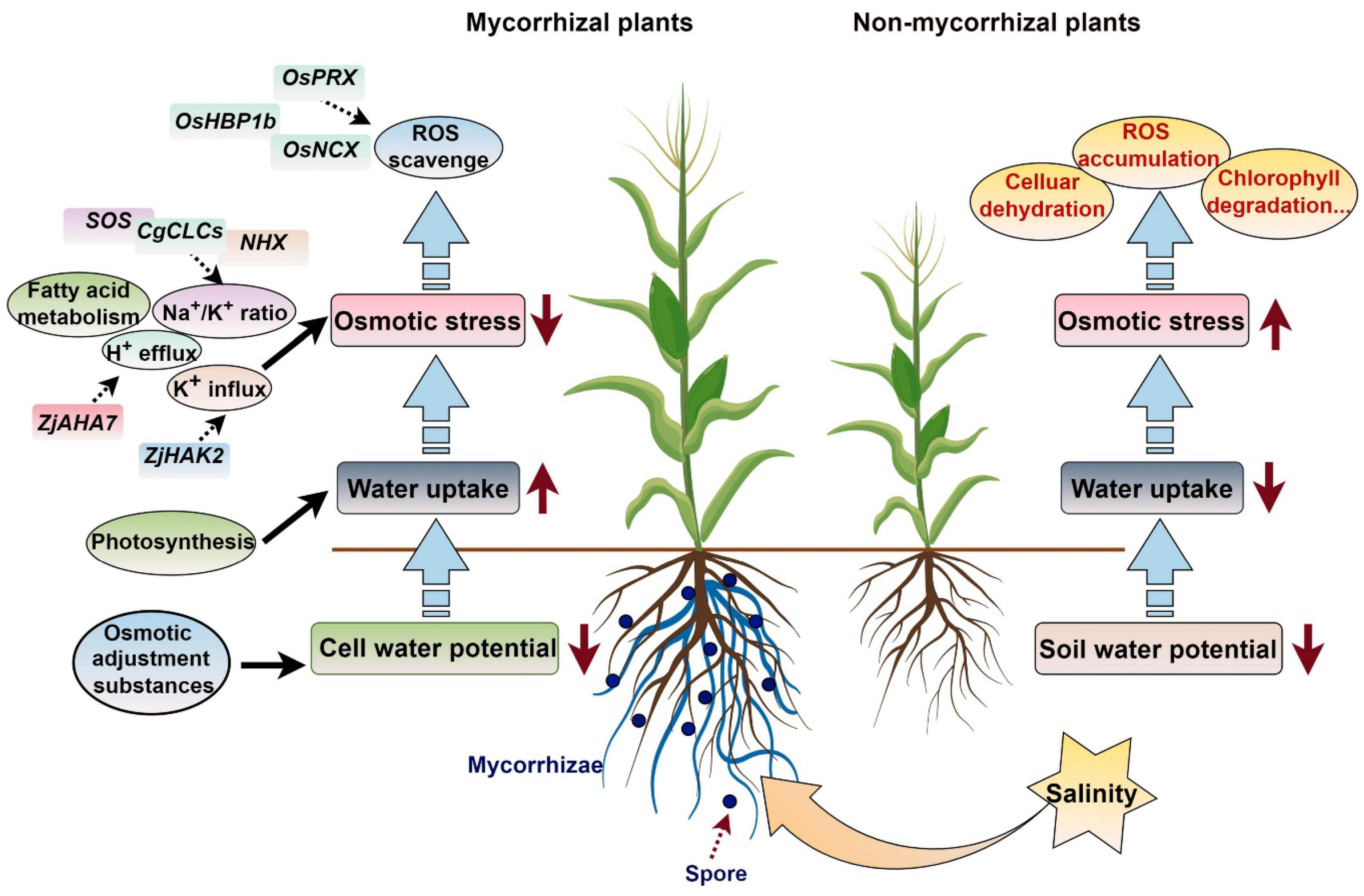

3.1.2. Salinity Stress

3.1.3. Temperature Extremes

3.1.4. Heavy Metal Stress

3.2. Biotic Stress and Its Mitigation Through Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi

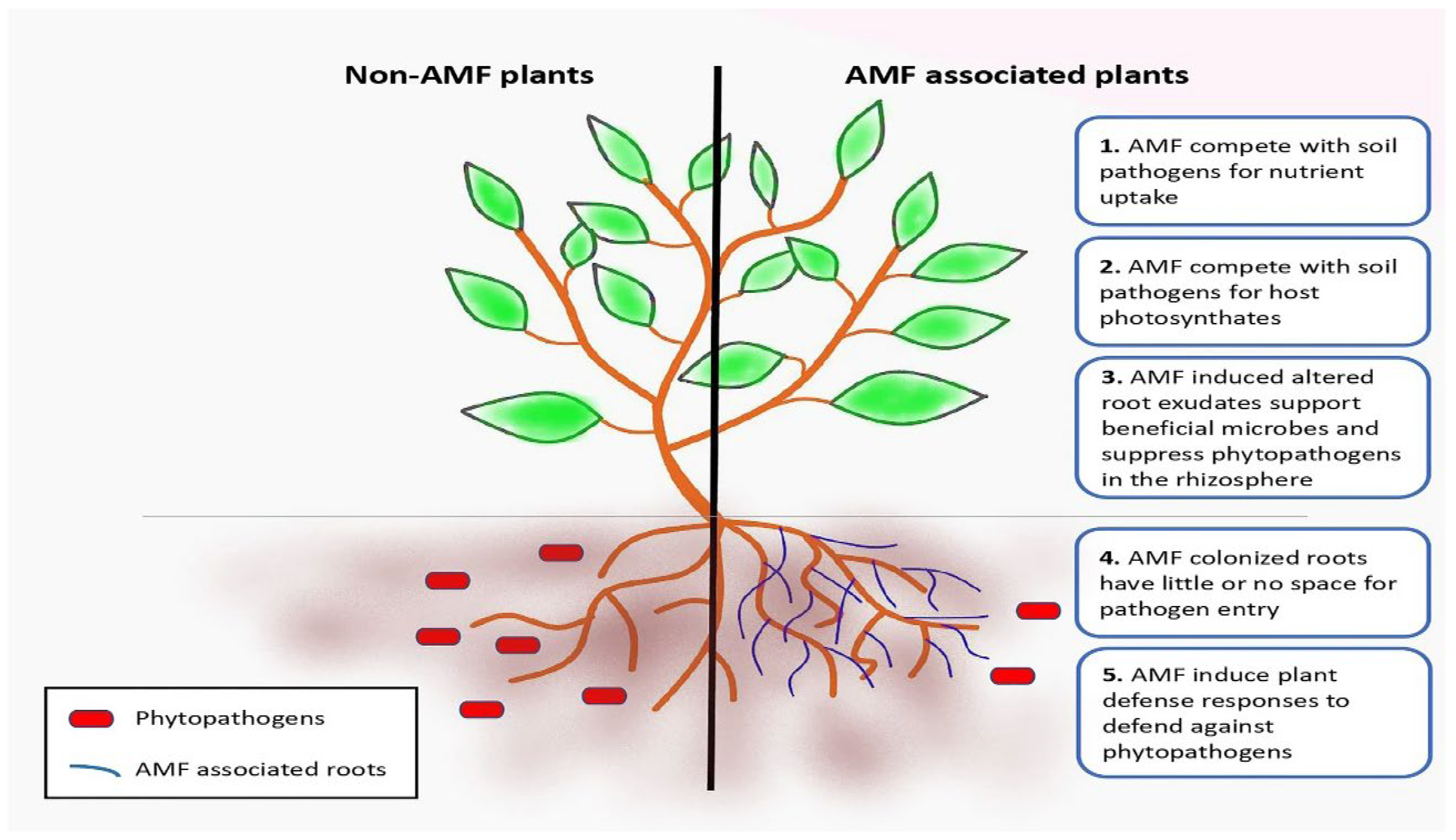

3.2.1. Pathogen Resistance

3.2.2. Insect Herbivory Resistance

3.2.3. Nematode Suppression

4. Co-Inoculation of AMF and Biostimulants

5. Limitations and Challenges

6. Future Technological Perspectives and Emerging Research Directions

7. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Microorganism | Abbreviated form | Reference |

| Claroideoglomus etunicatum | C. etunicatum | [10,51] |

| Claroideoglomus claroideum | C. cloroideum | [30,51,65] |

| Funnelliformis geosporus | F. geosporus | [51] |

| Funnelliformis mosseae | F. mosseae | [31,34,37,39,45,51,53,72,73,90] |

| Glomus intraradices | G. intraradices | [30,31,52,69,74] |

| Glomus mosseae | G. mosseae | [31,32,65,72,74] |

| Gigaspora margarita | G. margarita | [72] |

| Glomus gigantea | G. gigantea | [72] |

| Glomus viscosum | G. viscosum | [71] |

| Glomus aggregatum | G. aggregatum | [74] |

| Glomus monosporum | G. monosporum | [45] |

| Rhizophagus irregularis | R. irregularis | [35,37,39,45,48,51,59,67,90] |

| Rhizophagus intraradices | R. intraradices | [10,47] |

| Rhizophagus fasciculatus | R. fasciculatus | [49] |

| Septoglomus constrictum | S. consctictum | [10] |

| Bacillus megaterium | B. megaterium | [52,54] |

| Pantoea agglomerans | P. agglomerans | [54] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | P. fluorescens | [54] |

| Burkholderia cedrus | B. cedrus | [52] |

| Streptomyces beta-vulgaris | S. beta-vulgaris | [52] |

| Acronyms | Extended forms | |

| AMF | Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi | |

| CRU TS3.25 | Climatic Research Unit Time Series version 3.25 | |

| IR | Induced resistance | |

| MIR | Mycorrhiza-Induced Resistance | |

| NPK | Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), and Potassium (K) | |

| PGPR | Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria | |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses | |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species | |

| SAR | Systemic acquired resistance | |

References

- Begum, N.; Qin, C.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmed, N.; Zhang, L. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: Implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacete, A.; Ghanem, M.E.; Martínez-Andújar, C.; Acosta, M.; Sánchez-Bravo, J.; Martínez, V.; Lutts, S. Hormonal changes in relation to biomass partitioning and shoot growth impairment in salinized tomato plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 59, 4119–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wu, W.; Abrams, S.R.; Cutler, A.J. Drought-related gene expression in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 59, 2991–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardieu, F.; Tuberosa, R. Dissection and modelling of abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akula, R.; Ravishankar, G.A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahad, S.; Bajwa, A.A.; Nazir, U.; Anjum, S.A.; Farooq, A.; Zohaib, A.; Sadia, S.; Nasim, W.; Adkins, S.; Saud, S.; et al. Crop production under drought and heat stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.; de Vos, R.C.H.; Bones, A.M.; Hall, R.D. Plant molecular stress responses face climate change. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihorimbere, V.; Ongena, M.; Smargiassi, M.; Thonart, P. Beneficial plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2011, 15, 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bais, H.P.; Weir, T.L.; Perry, L.G.; Gilroy, S.; Vivanco, J.M. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, B.; Aroca, R.; Barea, J.M.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M. Native arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi isolated from a saline habitat improved maize antioxidant systems and plant tolerance to salinity. Plant Sci. 2013, 201–202, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinton, R.; Varanini, Z.; Nannipieri, P. The Rhizosphere as a Site of Heavy Metal Interactions between Soil, Microorganisms and Plants. In Soil Heavy Metals; Sherameti, I., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Jha, D.K. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): Emergence in agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 1327–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, A.; Azcón, R. Effectiveness of the application of arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi and organic amendments to improve soil quality and plant performance under stress conditions. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010, 10, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, G. Plant–microbe interactions promoting plant growth and health. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, C. Impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on N and P cycling in the root zone. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2004, 84, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Abbate, C.; Pandino, G.; Parisi, B.; Scavo, A.; Mauromicale, G. Potato grown under high-calcareous soils: Fertilization and mycorrhization. J. Agron. 2020, 10, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Anderson, I.C.; Smith, F.A. Mycorrhizal associations and phosphorus acquisition: From cells to ecosystems. In Annual Plant Reviews: Phosphorus Metabolism in Plants; Plaxton, W.C., Lambers, H., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 48, pp. 409–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelin, H.; Kapoor, R.; Giri, B. AMF and salt stress alleviation: A review. Ann. Bot. 2009, 104, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tang, M.; Sulpice, R.; Chen, H.; Tian, S.; Ban, Y. AMF alter fractal dimension characteristics of Robinia pseudoacacia under drought. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 33, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, U.; Regvar, M.; Bothe, H. AMF and heavy metal tolerance. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, F.; Li, B.; Jiang, M.; Yue, X.; He, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Y. AMF enhance antioxidant defense and heavy metal retention in maize roots. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 24338–24347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.J.; Azcón-Aguilar, C.; Ocampo, J.A. Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. In Induced Resistance for Plant Protection; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.E.; Bever, J.D. Mycorrhizal fungi mediate plant interactions with herbivores and pathogens. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 683–691. [Google Scholar]

- Adesemoye, A.O.; Torbert, H.A.; Kloepper, J.W. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria allow reduced application rates of chemical fertilizers. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 58, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.L.; Pepe, O. Microbial consortia as plant biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Naveed, M.; Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A. Rhizosphere bacteria for improving crop production under stress conditions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2013, 66, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandino, G.; Abbate, C.; Scavo, A.; Di Benedetto, D.; Mauromicale, G.; Lombardo, S. Co-inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting bacteria improves plant growth and yield of globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus scolymus). Sci. Hortic. 2023, 335, 113365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschmann, H. Mediterranean-type climate: A defined entity, a specific causal mechanism, and a worldwide distribution. In Mediterranean-Type Ecosystems: Origin and Structure; Kruger, F.J., Mitchell, D.T., Jarvis, J.U.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Lozano, J.M.; Aroca, R.; Zamarreño, M.J.; Azcón, R. Drought and plant–microbe interactions: Roles of plant hormones and microbial signals. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 205, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavito, M.E.; Olsson, P.A.; Rouhier, H.; Medina-Peñafiel, A.; Jakobsen, I.; Bago, A.; Azcón-Aguilar, C. Temperature constraints on the growth and functioning of root organ cultures with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2005, 168, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithra, D.; Yapa, P.N. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation enhances drought tolerance in soybean (Glycine max L.). Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.C.; Martinez-Medina, A.; Lopez-Raez, J.A.; Pozo, M.J. Mycorrhiza-induced resistance and priming. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujvári, G.; Turrini, A.; Avio, L.; Agnolucci, M. Possible role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and associated bacteria in the recruitment of endophytic bacterial communities by plant roots. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Cheng, W. Metabonomics reveals mechanisms of stress resistance in Vetiveria zizanioides inoculated with AMF under copper stress. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Ghosh, S. AMF in plant immunity and pathogen control. Rhizosphere 2022, 22, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.J.; Azcón-Aguilar, C. Unraveling mycorrhiza-induced resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowarah, B.; Gill, S.S.; Agarwala, N. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi confer tolerance to biotic stresses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Abrantes, F.; Congedi, L.; Dulac, F.; Gacic, M.; Gomis, D.; Goodess, G.; Hoff, H.; Kutiel, H.; Luterbacher, J.; et al. Introduction: Mediterranean Climate—Background Information. In The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From the Past to the Future; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; p. xxxv-xc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandino, G.; Lombardo, S.; Lo Monaco, A.; Ruta, C.; Mauromicale, G. In vitro micropropagation and mycorrhizal treatment influence polyphenol profiles of globe artichoke under field conditions. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seager, R.; Osborn, T.J.; Kushnir, Y.; Simpson, I.R.; Nakamura, J.; Liu, H. Climate Variability and Change of Mediterranean-Type Climates. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 2887–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuila, D.; Ghosh, S. Challenges of AMF as biofertilizers. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 10010712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance plant tolerance to salinity stress through ion homeostasis, antioxidant regulation, and osmotic adjustment pathways. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1323881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Agnihotri, R.; Sharma, M.P.; Reddy, V.R.; Jajoo, A. High temperature stress and AMF in maize. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebbane, M.; Labidi, S.; Hafsi, M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi symbiosis in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) under no-tillage and tillage practices in a semiarid region. Agric. Sci. Dig. 2023, 43, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejón, P.; Fernández-Boy, E.; Madejón, E.; Morales-Salmerón, L.; Domínguez, M.T. Tillage effects on triticale under water stress. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2025, 186, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.-X.; Xu, K.-X.; Guan, D.-X.; Liu, Y.-W.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Teng, H.H.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Ma, L.Q. Contrasting effects of arsenic on mycorrhizal-mediated silicon and phosphorus uptake by rice. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 124005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooja, P.; Devi, S.; Tallapragada, S.; Ahlawat, Y.K.; Sharma, N.; Kasnia, P.; Lakra, N.; Porcel, R.; Mulet, J.M.; Elhindi, K.M. Impact of AM symbiosis on photosynthetic, antioxidant, and water flux parameters in salt-stressed chickpea. Agronomy 2023, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Azid, A.; Hamid, F.S.; Pariatamby, A.; Ossai, I.C. Inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improved phytoremediation ability of Jatropha multifida L. in metal/metalloid contaminated landfill soil. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 12737–12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, B.; Soares, C.; Sousa, F.; Martins, M.; Mateus, P.; Rodrigues, F.; Azenha, M.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Lino-Neto, F. AMF and biochar enhance tomato tolerance to combined heat and salt stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 224, 104986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechri, B.; Tekaya, M.; Guesmi, A.; Ben Hamadi, N.; Khezami, L.; Soltani, T.; Attia, F.; Chehab, H. Enhancing olive tree (Olea europaea) rhizosphere dynamics: Co-inoculation effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth- promoting rhizobacteria in field experiments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirdel, M.; Eshghi, S.; Shahsavandi, F.; Fallahi, E. AM inoculation mitigates heat-stress effects on strawberry yield and physiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicer, S.; Erdinc, C.; Comlekcioglu, N. Co-inoculation of microbial biostimulants at different irrigation levels under field conditions affects cucumber growth. Gesunde Pflanz. 2023, 75, 1237–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversa, G.; Elia, A.; La Rotonda, P. Mycorrhizal inoculation and P fertilization effects on processing tomato. Acta Hortic. 2007, 758, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventis, G.; Tsiknia, M.; Feka, M.; Ladikou, E.; Papadakis, I.; Chatzipavlidis, I.; Papadopoulou, K.; Ehaliotis, C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance growth of tomato under normal and drought conditions, via different water regulation mechanisms. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karaki, G.N.; Hammad, R.; Rusan, M. Response of two tomato cultivars differing in salt tolerance to inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi under salt stress. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, J.; Hernández, J.A.; Caravaca, F.; Roldán, A. Antioxidant enzymes in PGPR vs. AMF under salinity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras-Soriano, A.; Soriano-Martín, M.L.; Porras-Piedra, A.; Azcón, R. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi increased growth, nutrient uptake and tolerance to salinity in olive trees under nursery conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 166, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Gelani, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Heat tolerance in plants: An overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, L.M.; Ma, L.Q.; Santos, J.A.G.; Guilherme, L.R.G.; Lessl, J.T.; Mello, J.W.V. Effects of arsenate, chromate, and sulfate on arsenic and chromium uptake and translocation by arsenic hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata L. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higueras-Valdivia, M.; Silva-Castro, G.A.; Paniagua-López, M.; Romero-Freire, A.; García-Romera, I. Mitigation of heavy metal soil contamination: A novel strategy with mycorrhizal fungi and biotransformed olive residue. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, A.; Saran, M.; Giovannetti, M.; Oehl, F. Rhizoglomus venetianum, a new AMF species from a heavy metal-contaminated site. Mycol. Prog. 2018, 17, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, S.E.; Gange, A.C. Impacts of plant symbiotic fungi on insect herbivores: A hidden world of interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2009, 54, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, R.; Biere, A.; Harvey, J.A.; Bezemer, T.M. Soil organisms influence aboveground plant–insect interactions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.D.; Neal, A.L.; van Wees, S.C.M.; Ton, J. Mycorrhiza-induced resistance: More than the sum of its parts? Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacott, C.N.; Murray, J.D.; Ridout, C.J. Trade-offs in AMF symbiosis. Agronomy 2017, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, A.; Gervacio, D.; Swennen, R.; De Waele, D. AMF-induced biocontrol against nematodes in Musa. Plant Soil 2008, 308, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, E.C.; Owen, K.J.; Zwart, R.S.; Thompson, J.P. AMF effects on root-lesion nematodes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Tommasi, F.; Paciolla, C. The Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Glomus viscosum Improves the Tolerance to Verticillium Wilt in Artichoke by Modulating the Antioxidant Defense Systems. Cells 2021, 10, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, G.M.; El-Haddad, S.A.; Hafez, E.E.; Rashad, Y.M. Induction of defense responses in common bean plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 166, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouteden, N.; de Waele, D.; Panis, B.; Vos, C.M. AMF for biocontrol of plant-parasitic nematodes: Mechanisms involved. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Chavana, J.; Soti, P.; Racelis, A.; Kariyat, R. AMF influence growth and insect dynamics in sorghum–sudangrass. Arthropod–Plant Interact. 2020, 14, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostadi, A.; Javanmard, A.; Machiani, M.A.; Sadeghpour, A.; Maggi, F.; Nouraein, M.; Morshedloo, M.R.; Hano, C.; Lorenzo, J.M. Co-Application of TiO2 Nanoparticles and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Improves Essential Oil Quantity and Quality of Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) in Drought Stress Conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, C.M.; Tesfahun, A.N.; Panis, B.; De Waele, D.; Elsen, A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce systemic resistance in tomato against Meloidogyne incognita and Pratylenchus penetrans. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 61, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, B.S.; Chaudhary, P.; Ayilara, M.S.; Ojo, F.M.; Erinoso, S.M.; Upadhayay, V.K.; Adeyemo, A.I.; Akinola, S.A. Rhizosphere microbiomes mediating abiotic stress mitigation for improved plant nutrition. Ecologies 2024, 5, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizos, G.; Papatheodorou, E.M.; Chatzistathis, T.; Ntalli, N.; Aschonitis, V.G.; Monokrousos, N. Microbial. The Role of Microbial Inoculants on Plant Protection, Growth Stimulation, and Crop Productivity of the Olive Tree (Olea europea L.). Plants 2020, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Chahal, K.; Gupta, V.; Chaurasia, A.; Rana, B. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: A potential tool for sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Role of AMF in regulating growth, productivity, and ecosystems under stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hol, W.H.G.; Cook, R. An overview of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi–nematode interactions. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2005, 6, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, M.M.; Torrecillas, E.; Hernández, G.; Roldán, A. Differences in the composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in wild and cultivated Olea europaea L. under the influence of fertilization and tillage. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Koziol, L.; Lubin, T.; Bever, J.D. An assessment of twenty-three mycorrhizal inoculants reveals limited viability of AM fungi, pathogen contamination, and negative microbial effect on crop growth for commercial products. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigle, T.P.; Miller, M.H.; Evans, D.G.; Fairchild, G.L.; Swan, J.A. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular–arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrassini, V.; Ercoli, L.; Aguilar Paredes, A.V.; Pellegrino, E. Positive response to inoculation with indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as modulated by barley genotype. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 45, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.M.; Campos, E.V.R.; de Oliveira, F.F.; Rodrigues, J.S.; de Freitas Proença, P.L.; Melo, A.A.; Fraceto, L.F. Harnessing nanotechnology and bio-based agents: Advanced strategies for sustainable soybean nematode management. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 13, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.N.Y.; Kuca, K.; Dhalaria, R. Economic Analysis of Mycorrhizal Applications and Their Potential for Enhancing Farm Profitability and Livelihoods. In Sustainable Mycorrhizal Cultivation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.; Maucieri, C.; Berruti, A.; Borin, M.; Barbera, A.C. Responses of Panicum miliaceum genotypes to saline and water stress. Agronomy 2018, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyno, G.; Rezaee Danesh, Y.; Çevik, R.; Teniz, N.; Demir, S.; Demirer Durak, E.; Farda, B.; Mignini, A.; Djebaili, R.; Pellegrini, M.; et al. Synergistic benefits of AMF: Development of sustainable plant defense system. Front. Micro-Biol. 2025, 16, 1551956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorui, M.; Chowdhury, S.; Burla, S. Recent advances in the commercial formulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculants. Front. Ind. Microbiol. 2025, 3, 1553472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Species | Stress Agent | AMF | Effect Detail | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poaceae | Zea mays | High temperatures 42 °C | Rhizophagus irregularis, Funneliformis mosseae, Glomus spp. | • Reduction in oxidative stress (−47%); • Improvement in chlorophyll pigmentation (+85%). | [45] |

| Zea mays | Salinity | R. intraradices, S. constrictum, Claroideoglomus etunicatum | At 100 mM NaCl, root colonization was: • 84.3% (R. intraradices); • 77.3% (C. etunicatum). indicating different responses depending on the AMF species | [10] | |

| Triticum durum | Drought | Indigenous 1AMF consortia | 54% increase in root colonization with no-tillage practices compared to conventional tillage. | [46] | |

| Triticale hexaploide | Drought | Indigenous 1AMF consortia | With conservation tillage, increasing in the following: the abundance of vesicles (+6%) and arbuscules (+5%). | [47] | |

| Oryza sativa | Arsenic | R. irregularis | Phytoextraction: Increasing As accumulation in the following: • roots (+38%); • aerial parts (+55%). | [48] | |

| Vetiveria zizanioides | Copper | F. mosseae | Increase in the following: • height (+38%); • biomass (+32%). Reduction in Cu content in leaves (up to −111.2%). | [34] | |

| Fabaceae | Glycine max | High-input systems + Drought | G. intraradices G. mosseae | No effect on biometric parameters. Increase in the following: • photosynthetic rate; • soil moisture content. Reduction in proline accumulation. | [31] |

| Cicer arietinum | Salinity | R. fasciculatus | Increasing activity of antioxidant enzymes: • Superoxide Dismutase (+20–23%); • Catalase (+18%); • Peroxidase (+30%). | [49] | |

| Pongamia pinnata | Nickel | 1AMF microbial consortium | Phytoremediation: High Ni removal efficiency (90–93%) from the substrate. | [50] | |

| Solanaceae | Solanum lycopersicum | Salinity + High temperatures +42 °C | R. irregularis, C. etunicatum, C. claroideum, F. mosseae, F. geosporus | Reduction in the following: • flower drop; • Na accumulation (−25%). Increase in the following: • fruit set (+71%); • fresh weight (+30%); • Ca uptake (+20%); • Mg uptake (+15%). Improvement in CO2 assimilation (+ 40%). | [51] |

| Asteraceae | C. cardunculus var. scolymus | Drought | F. mosseae, R. irregulare | Increase in caffeoylquinic acids. Root colonization maintained under stress: 25%. | [39] |

| C. cardunculus var. scolymus | Co-inoculum 1AMF + 2PGPR | Glomus spp + 2PGPR (Bacillus spp., Azotobacter spp.) | Increase in the following: • aerial biomass (+23%); • fresh weight yield (+54%). | [27] | |

| Oleaceae | Olea europaea | Salinity | R. irregularis | Reduction in Na in leaves Increase in the following: • relative water content; • K+/Na+ ratio. | [48] |

| Olea europaea | Co-inoculum 1AMF + 2PGPR | G. intraradices + 2PGPR | Improved uptake of the following: • N (+26%); • P (+60%); • Fe (+25%); • other nutrients. | [52] | |

| Rosaceae | Fragaria ananassa | High temperatures 42 °C | F. mosseae | Increase in the following: • fruit weight (+11%); • yield (+6%); • photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm); Reduction in membrane damage. | [53] |

| Apiaceae | Daucus carota | Low temperatures 15 °C | G. intraradices, G. claroideum, G. mosseae | Reduction in hyphal growth sporulation (60–70%), with G. intraradices being more tolerant to cold. | [30] |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis sativus | Drought | Mix of 1AMF + 2PGPR (Bacillus, Pantoea, Pseudomonas) | Increase in the following: • yield (+34%); • water use efficiency. | [54] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha curcas | Nickel | 1AMF microbial consortium | Ni removal efficiency from 82% to 86%. | [50] |

| Family | Species | Stress Agent | AMF | Effect Detail | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fabaceae | Phaseolus vulgaris | Rhizoctonia solani | Mix: Glomus mosseae, G. intraradices, G. clarum, G. gigantea, G. margarita | Reduction in disease incidence (from 100% to 73.3%) and severity (from 100% to 66.3%). | [72] |

| Glycine max | Aulacorthum solani | Gigaspora margarita | Negative: The aphid was 10 times more abundant on inoculated plants. | [66] | |

| Glycine max | herbivorous insects | 1AMF | No effect: 75% of interactions are neutral; Positive: 25% for interaction (reduced larval biomass). | [66] | |

| Glycine max | Meloidogyne incognita | Funneliformis mosseae | The following reductions: • 60% infection; • 27–32% egg hatching. | [32,73] | |

| Solanaceae | Solanum lycopersicum | Alternaria solani, Botrytis cinerea Pratylenchus penetrans | Rhizophagus irregularis G. mosseae | Increase in resistance to foliar pathogens. Reduction of 87% in nematode population in root. | [67] |

| Poaceae | Oryza sativa | Magnaporthe oryzae, Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus | R. irregularis | Increase in resistance to the pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae and the insect Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus. | [35,37] |

| Sorghum vulgare | Spodoptera frugiperda | G. intraradices, G. mosseae, G. aggregatum, G. monosporum | Significant reduction in insect incidence compared to the control. | [74] | |

| Asteraceae | Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus | Verticillium dahliae | G. viscosum | Mitigation of infections | [71] |

| Plantaginaceae | Plantago lanceolata | Arctia caja | G. intraradices, G. claroideum, G. mosseae | Larvae of Arctia caja consumed 77–82% less plant material from non-mycorrhizal plants. | [65] |

| Rubiaceae | Coffea arabica | Meloidogyne | Indigenous 1AMF consortia | Average reduction in infection severity of 38.3–52.5%. | [35] |

| Musaceae | Musa paradisiaca | R. similis and P. coffeae | G. intraradices | Reduction in nematode population by 72% (R. similis) and 84% (P. coffeae). | [69] |

| Poaceae | Grasses | Pratylenchus | Glomerales, Glomus, Funneliformis | Meta-analysis: • decrease in 36.6% of cases; • no effect in 46.6% of cases; • increase in 16.6% of cases. | [70] |

| Species | Technology Applied | Effect Detail | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus | In vitro micropropagation combined with 1AMF inoculation | Increased phenolic compound accumulation | [39] |

| C. cardunculus var. scolymus | Co-inoculation 1AMF + 2PGPR | Increased aerial biomass and head yield; improved functional quality traits | [27] |

| Olea europaea | 1AMF inoculation combined with 2PGPR consortia (field trial) | Increased macro- and micronutrient uptake and enhanced secondary metabolite accumulation (oleuropein; verbascoside) | [52] |

| Triticum aestivum | Native 1AMF isolates for phytoremediation | Improved biomass and photosynthetic efficiency in heavy-metal contaminated soils | [63] |

| Zea mays | Native 1AMF isolated from saline Mediterranean soils | Enhanced antioxidant systems and higher salinity tolerance | [10] |

| Glycine max | Nanotechnology + RNA interference delivery | Highly specific suppression of plant-parasitic nematodes | [17] |

| Salvia officinalis | Co-application of TiO2 nanoparticles + 1AMF | Increased essential oil quantity and improved quality under drought stress | [75] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Formenti, C.; Mauromicale, G.; Pandino, G.; Lombardo, S. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Mitigate Crop Multi-Stresses Under Mediterranean Climate: A Systematic Review. Agronomy 2026, 16, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010113

Formenti C, Mauromicale G, Pandino G, Lombardo S. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Mitigate Crop Multi-Stresses Under Mediterranean Climate: A Systematic Review. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010113

Chicago/Turabian StyleFormenti, Claudia, Giovanni Mauromicale, Gaetano Pandino, and Sara Lombardo. 2026. "Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Mitigate Crop Multi-Stresses Under Mediterranean Climate: A Systematic Review" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010113

APA StyleFormenti, C., Mauromicale, G., Pandino, G., & Lombardo, S. (2026). Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Mitigate Crop Multi-Stresses Under Mediterranean Climate: A Systematic Review. Agronomy, 16(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010113