Selection of High-Yield Varieties (Lines) and Analysis on Molecular Regulation Mechanism About Yield Formation of Seeds in Alfalfa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Materials

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. Experimental Design

2.3.2. Soil Sampling and Determination of Available Phosphorus

2.3.3. Measurement of Alfalfa Agronomic Trait Indices

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. Transcriptome Data Sequencing and Gene Expression Validation

2.6. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Genetic Variation in Agronomic Traits Among Different Alfalfa Accessions

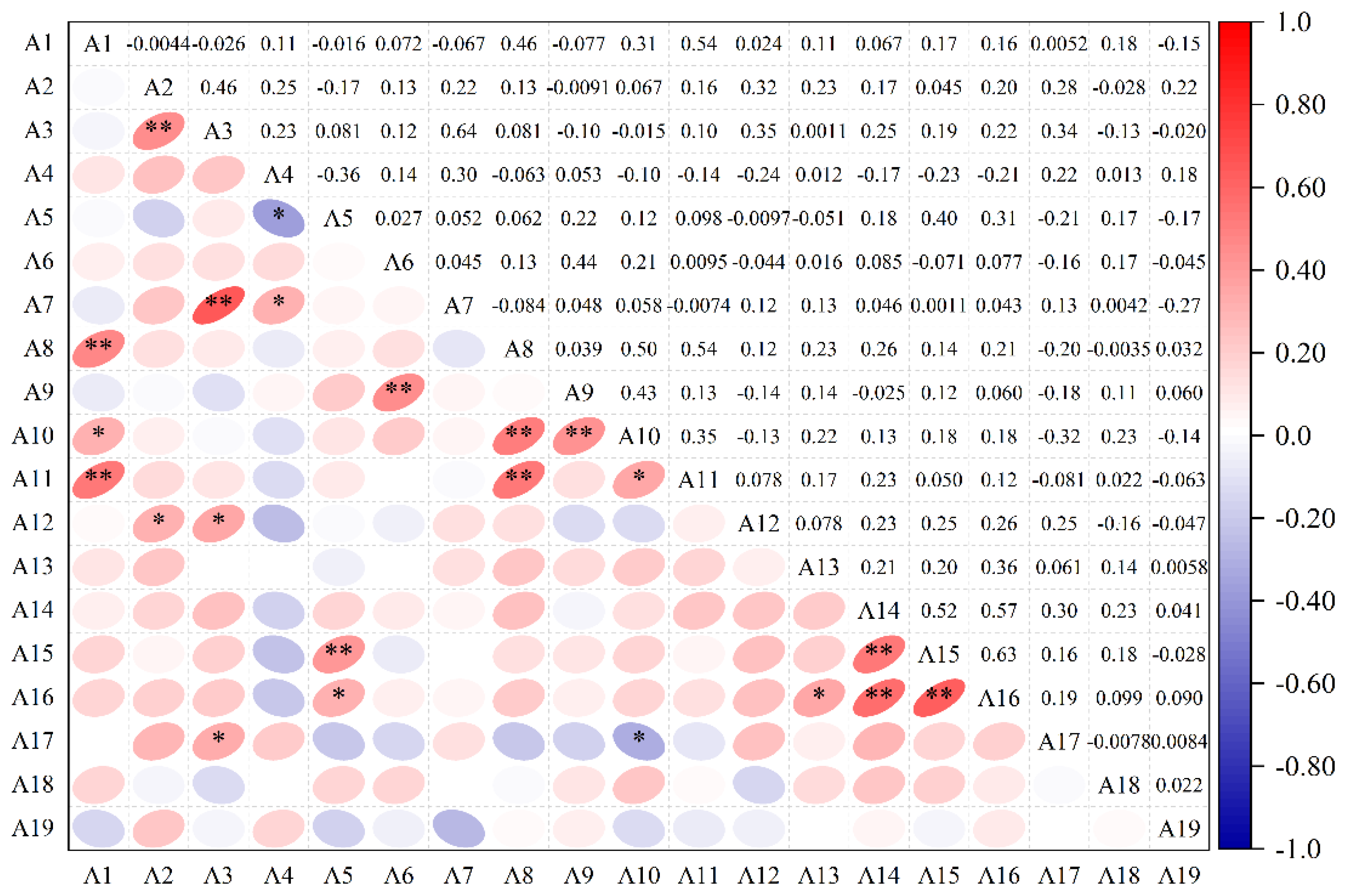

3.2. Correlation Analysis of Alfalfa Agronomic Traits

3.3. Principal Component Analysis of Alfalfa Agronomic Traits and Screening for High-Yield Germplasm

3.4. Linear Regression and Path Analysis of Agronomic Traits and Yield

3.5. Cluster Analysis of Alfalfa Accessions Based on Agronomic Traits

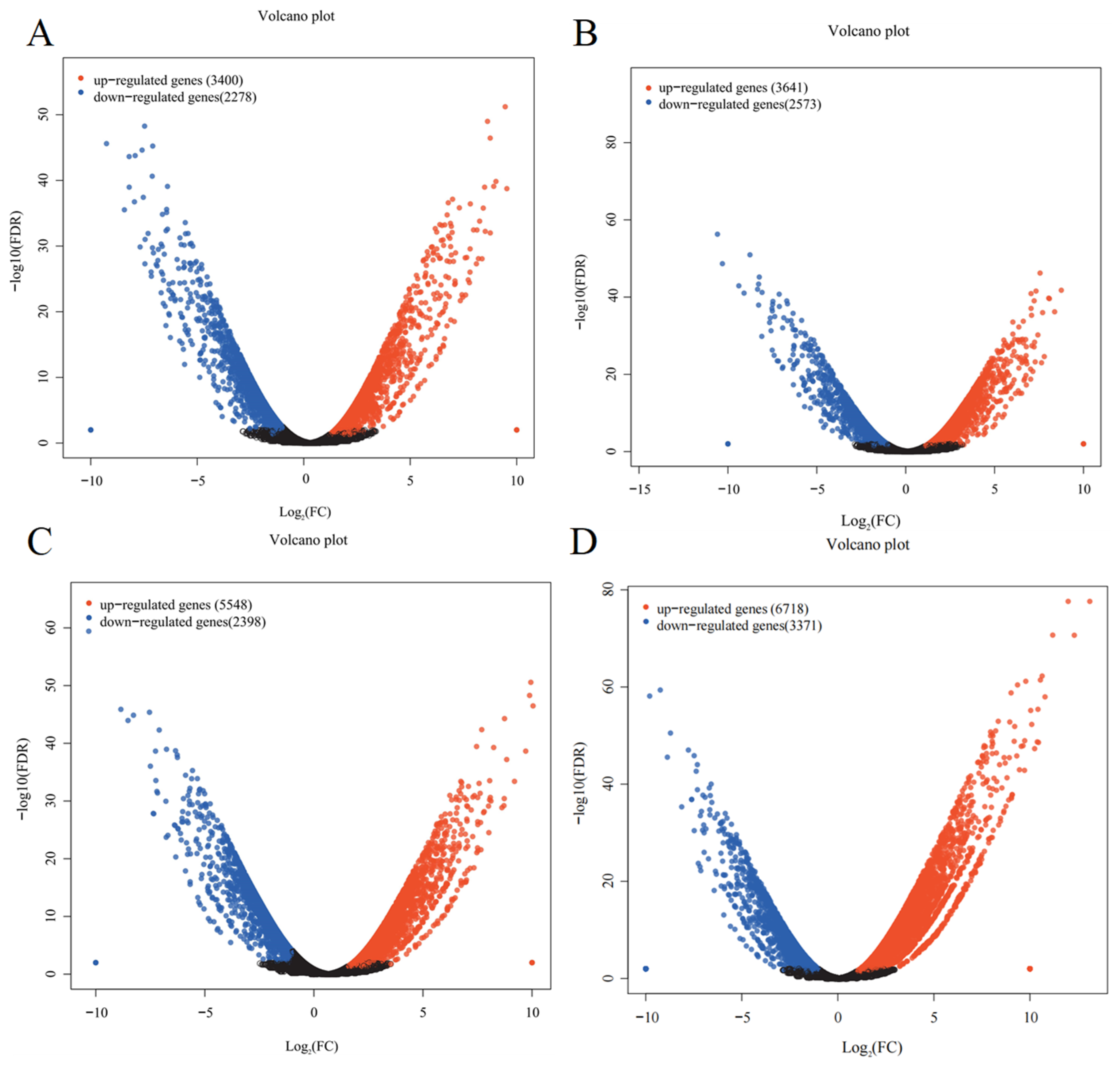

3.6. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes in Different Tissues of Medicago sativa (Alfalfa)

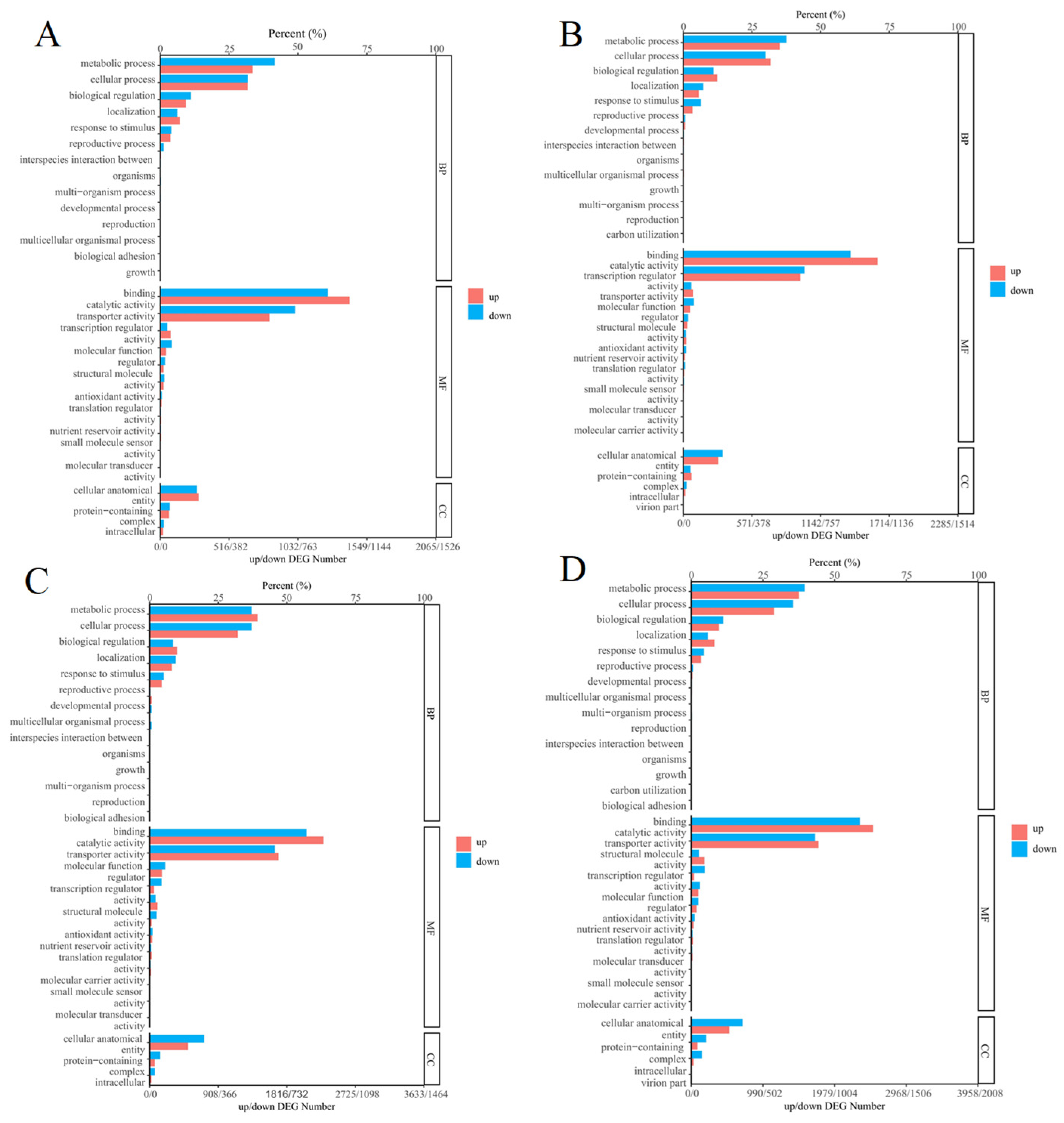

3.7. GO Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in Different Tissues of Medicago sativa

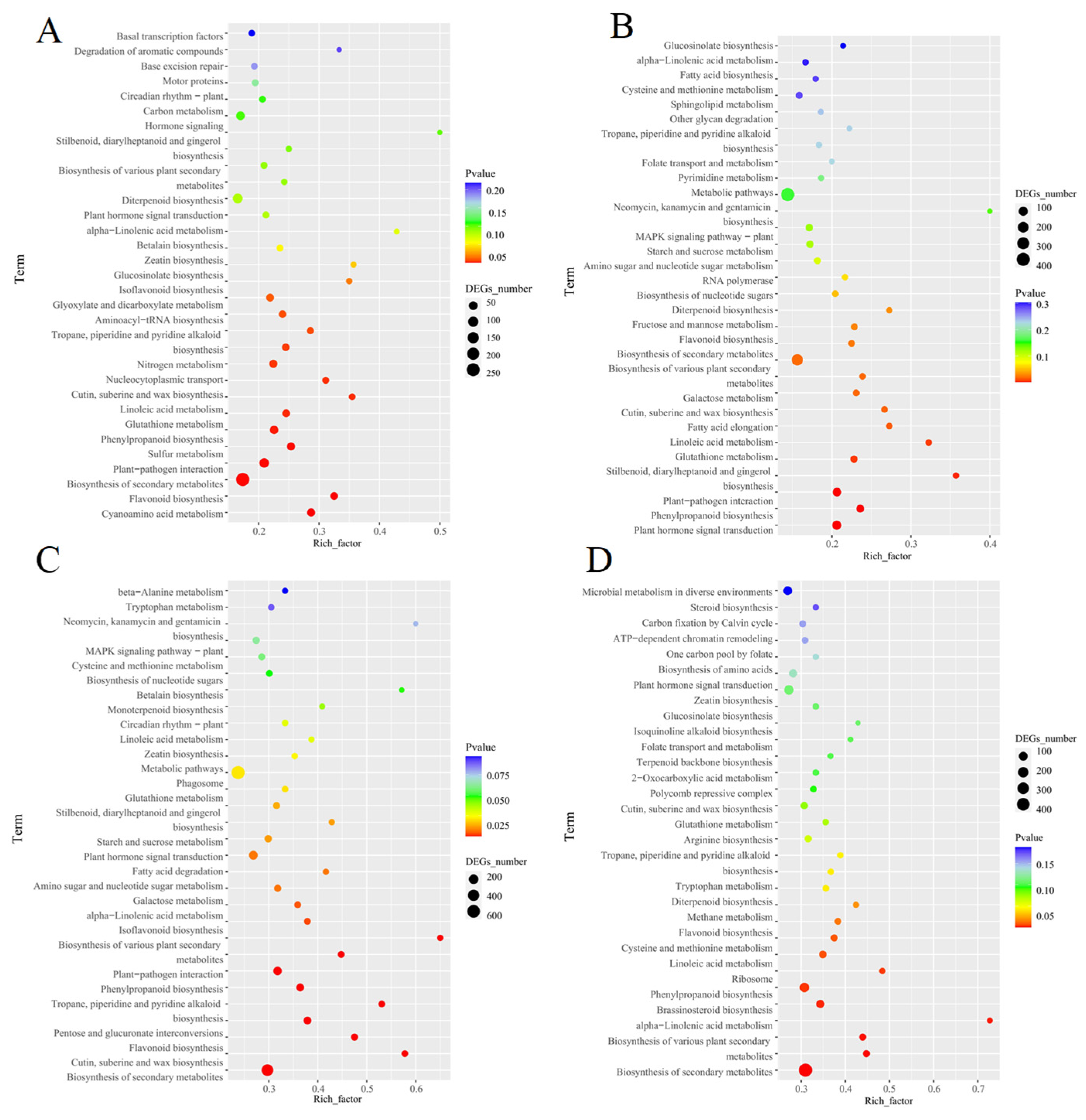

3.8. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in Different Tissues of Medicago sativa

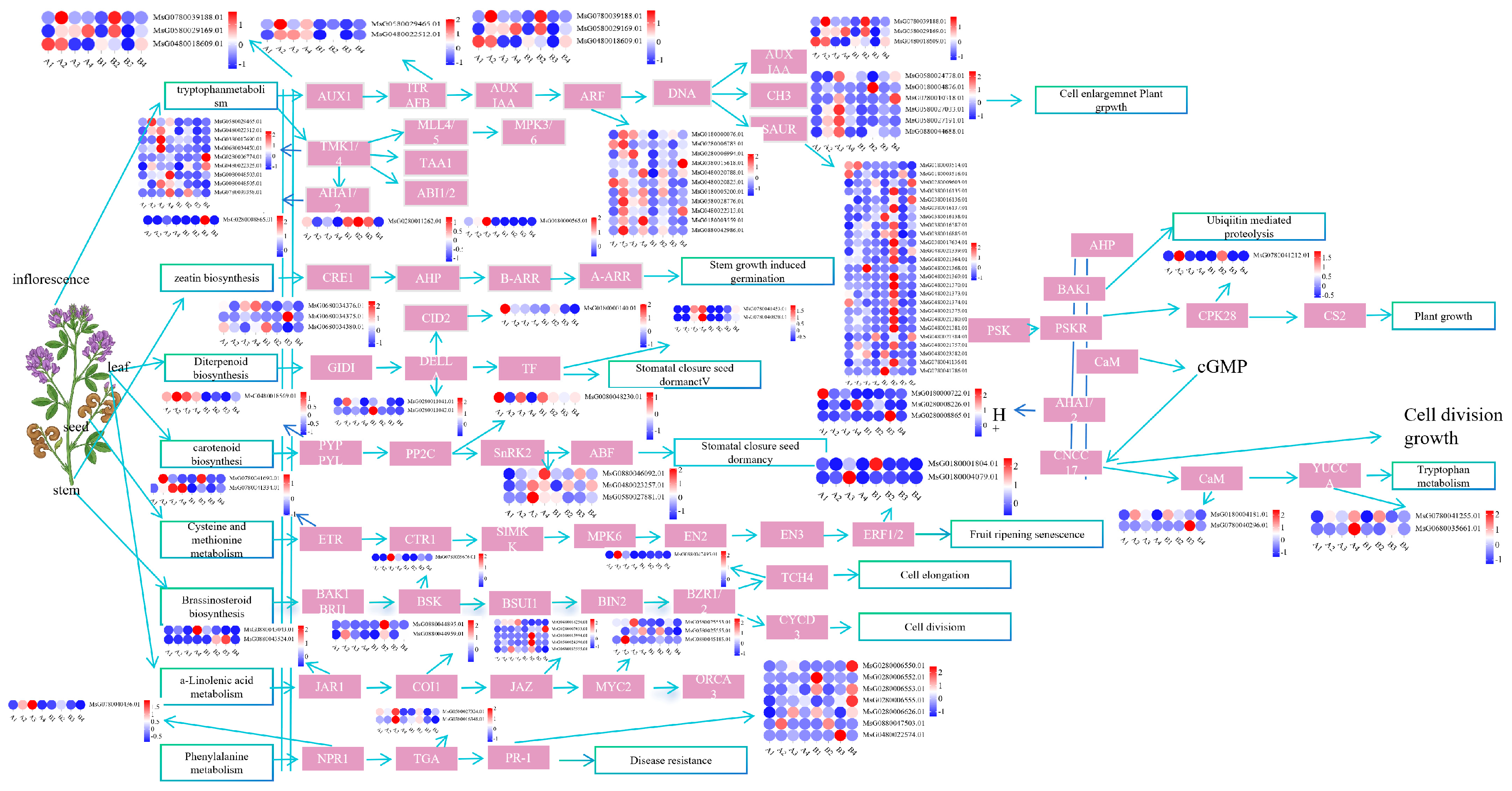

3.9. Analysis of Hormone Signal Transduction Pathways in Alfalfa

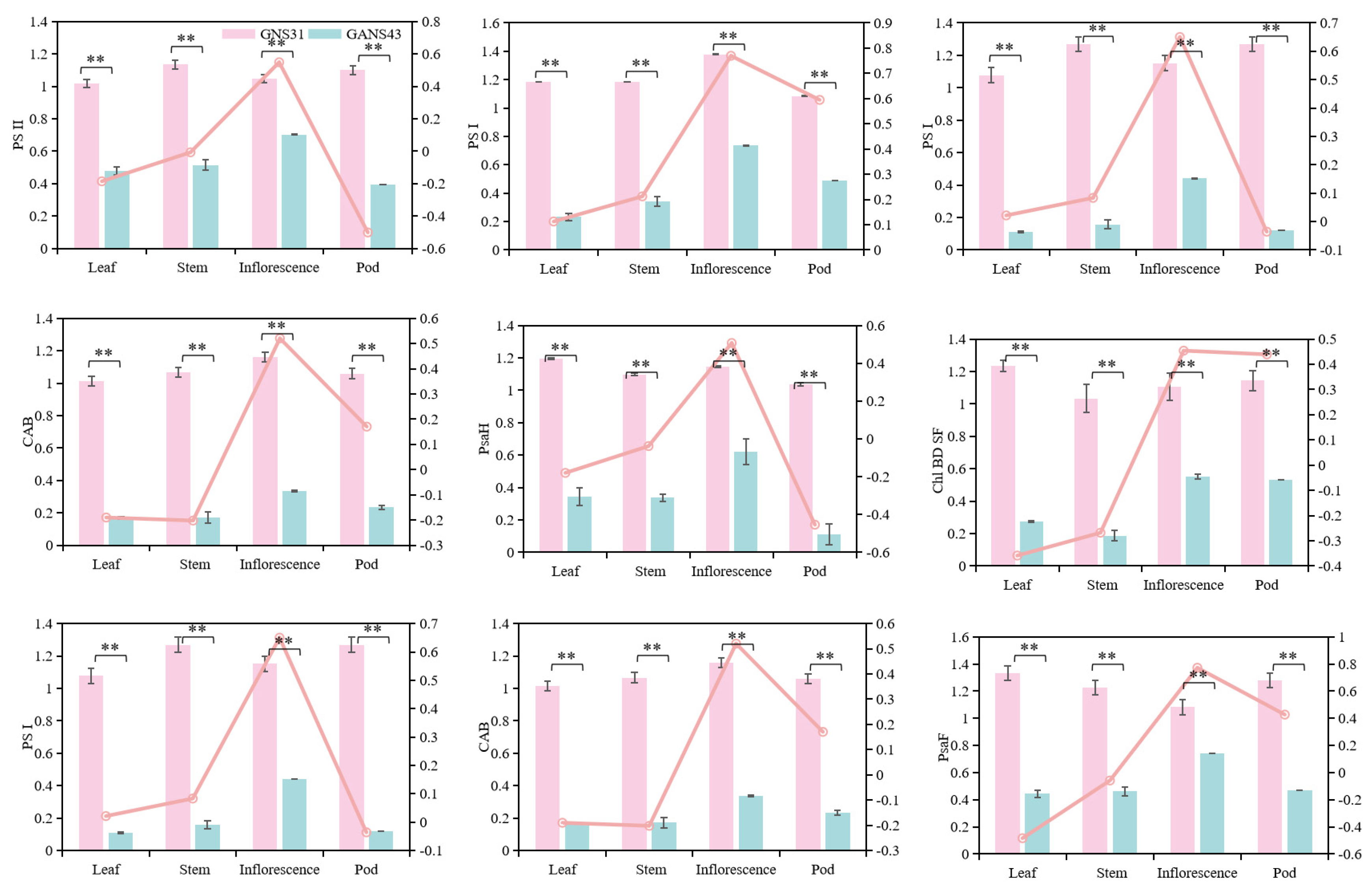

3.10. RT-qPCR Validation of Differentially Expressed Genes

4. Discussion

4.1. Investigation of Coefficient of Variation and Correlation Analysis of Agronomic Traits in Medicago sativa for High-Yield Breeding

4.2. Synergistic Evaluation of Medicago sativa Varieties/Lines Through Multi-Dimensional Analysis

4.3. Tissue-Specific Transcriptional Differences Between Medicago sativa Varieties

4.4. Mechanism of Alfalfa Yield Formation Co-Regulated by Hormone Signal Transduction and Carbon Metabolism

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schnurr, J.A.; Jung, H.J.G.; Samac, D.A. A comparative study of alfalfa and Medicago truncatula stem traits: Morphology, chemical composition, and ruminal digestibility. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annicchiarico, P.; Piano, E. Use of artificial environments to reproduce and exploit genotype× location interaction for lucerne in northern Italy. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Elzenga, J.T.M.; Venema, J.H.; Tiedge, K.J. Thriving in a salty future: Morpho-anatomical, physiological and molecular adaptations to salt stress in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and other crops. Ann. Bot. 2024, 134, 1113–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, J.P.; Lopez, Y.; Gouveia, B.T.; de Bem Oliveira, I.; Resende, M.F., Jr.; Muñoz, P.R.; Rios, E.F. Breeding alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) adapted to subtropical agroecosystems. Agronomy 2020, 10, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Qi, G.; Yin, M.; Kang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y. Alfalfa cultivation patterns in the Yellow River Irrigation Area on soil water and nitrogen use efficiency. Agronomy 2024, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Improving China’s alfalfa industry development: An economic analysis. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, Y.; Wan, L. Potential analysis and policy recommendations for restructuring the crop farming and developing forage industry in China. Strateg. Study Chin. Acad. Eng. 2016, 18, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Mikhael, J.E. The Effects of Biochar and Nitrogen Stabilizers Application on Forage Crop Growth, Greenhouse Gas Emission and Soil Quality; Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Shen, B.; Kong, X.; Sawadgo, W.; Li, W. 2024 Q1 Agricultural Trade Series: US-China Trade Trends and Opportunities for Alfalfa Exports. Plains Press. 2024. Available online: https://plainspress.scholasticahq.com/article/124556.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Shi, S.; Nan, L.; Smith, K.F. The current status, problems, and prospects of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) breeding in China. Agronomy 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Cai, W.; Pan, J.; Su, X.; Dou, L. Molecular Mechanisms of Alfalfa Response to Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2025, 14, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Deng, X.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, H.c. Forage Crop Research in the Modern Age. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2415631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Hasan, M.K.; Islam, M.R.; Chowdhury, M.K.; Pramanik, M.H.; Iqbal, M.A.; Rajendran, K.; Iqbal, R.; Soufan, W.; Kamran, M. Water relations and yield characteristics of mungbean as influenced by foliar application of gibberellic acid (GA3). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1048768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, R.M.; Boulisset, F.; Conreux, C.; Thompson, R.; Ochatt, S.J. In vitro auxin treatment promotes cell division and delays endoreduplication in developing seeds of the model legume species Medicago truncatula. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 148, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desta, B.; Amare, G. Paclobutrazol as a plant growth regulator. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Q. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus addition on agronomic characters, photosynthetic performance and anatomical structure of alfalfa in northern xinjiang, China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Hernandez, T.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Z.-Y. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). In Agrobacterium Protocols; Springer: Humana Totowa, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Tang, B.; Zhang, H.; Hao, F.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Allele-aware chromosome-level genome assembly and efficient transgene-free genome editing for the autotetraploid cultivated alfalfa. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, T.; Yu, L.X.; He, F.; et al. Genome Assembly of Alfalfa Cultivar Zhongmu-4 and Identification of SNPs Associated with Agronomic Traits. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Du, H.; Chen, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhu, F.; Chen, H.; Meng, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, P.; Zheng, L. The chromosome-level genome sequence of the autotetraploid alfalfa and resequencing of core germplasms provide genomic resources for alfalfa research. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, E.; Massa, G.; González, M.; Stritzler, M.; Tajima, H.; Gómez, C.; Frare, R.; Feingold, S.; Blumwald, E.; Ayub, N. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in alfalfa using a public germplasm. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 661526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolabu, T.W.; Cong, L.; Park, J.-J.; Bao, Q.; Chen, M.; Sun, J.; Xu, B.; Ge, Y.; Chai, M.; Liu, Z. Development of a highly efficient multiplex genome editing system in outcrossing tetraploid alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, T.; Yu, L.-X.; He, F. Assembly of chromosome-scale and allele-aware autotetraploid genome of the Chinese alfalfa cultivar Zhongmu-4 and identification of SNP loci associated with 27 agronomic traits. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.K.; Barwal, S.K.; Moni, A. Exploring the impact of integrated breeding strategies in enhancing yield, nutritional quality, and stress tolerance in alfalfa. Plant Trends 2023, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Chen, L.; Chen, F.; Ma, H. Genome-wide identification of SHMT family genes in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and its functional analyses under various abiotic stresses. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Lin, Z.-S.; Du, L.-P.; Ma, H.-L.; Xiao, L.-L.; Ye, X.-G. Production and identification of haploid dwarf male sterile wheat plants induced by corn inducer. Bot. Stud. 2014, 55, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.R.; Navarro, L. Citrus Germplasm Resources; CABI Digital Library: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 45–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Yong, X.; Xiao-Fen, C.; An, W.; Fei, T.; Li-qun, S.; Qiao-quan, L. A genetic diversity assessment of starch quality traits in rice landraces from the Taihu basin, China. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wen, X.; Zhang, R.; Xing, X. Current Situation and Utilization of Velvet Deer Germplasm Resources in China. Animals 2022, 12, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Ying, J. Advances in Crop Molecular Breeding and Genetics; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2025; 340p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.G.D. Alfalfa Breeding for Cultivation in the Tropics: Insights on Genetic Diversity and Yield Persistence. 2021. Available online: https://locus.ufv.br/server/api/core/bitstreams/c7e910e0-6041-4152-b12b-6a42861afaf3/content (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Kong, F.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Comparison of Nutritional Components, Ruminal Degradation Characteristics and Feed Value from Different Cultivars of Alfalfa Hay. Animals 2023, 13, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monirifar, H. Path analysis of yield and quality traits in alfalfa. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2011, 39, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hifny, Z.; Bakheit, B.; Hassan, M.; Abd El-Rady, W. Forage and seed yield variation of alfalfa cultivars in response to planting date. SVU-Int. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 1, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.; Bhering, L.; Ferreira, R.d.P. Biometric procedures applied to genetic improvement of alfalfa. In Genetic Improvement of Alfalfa; Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation: Brasília, Brazil, 2025; Available online: http://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/handle/doc/1171631 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, W.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cai, T.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chang, C.; Yin, Q.; Jiang, X.; et al. Multi-omics analyses reveal new insights into nutritional quality changes of alfalfa leaves during the flowering period. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 995031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Li, J.; Lei, H.; Yan, M.; Wang, Q.; Ji, R.; Zhang, S.; Min, X.; Sun, Z.; Wei, Z. PCA-Driven Multivariate Trait Integration in Alfalfa Breeding: A Selection Model for High-Yield and Stable Progenies. Plants 2025, 14, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meskiene, I.; Bögre, L.; Dahl, M.; Pirck, M.; Ha, D.; Swoboda, I.; Heberle-Bors, E.; Ammerer, G.; Hirt, H. cycMs3, a novel B-type alfalfa cyclin gene, is induced in the G0-to-G1 transition of the cell cycle. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.-S.; Zhang, Z. Proteomic changes in the xylem sap of Brassica napus under cadmium stress and functional validation. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Elias, N.C.; Martínez-Barajas, E.; Bernal-Gracida, L.A.; Vázquez-Sánchez, M.; Galván-Escobedo, I.G.; Rodriguez-Zavala, J.S.; López-Herrera, A.; Peña-Valdivia, C.B.; García-Esteva, A.; Cruz-Cruz, C.A. Sucrose synthase gene family in common bean during pod filling subjected to moisture restriction. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1462844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ren, Z.; Ma, H. Selection of High-Yield Varieties (Lines) and Analysis on Molecular Regulation Mechanism About Yield Formation of Seeds in Alfalfa. Agronomy 2026, 16, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010108

Ren Z, Ma H. Selection of High-Yield Varieties (Lines) and Analysis on Molecular Regulation Mechanism About Yield Formation of Seeds in Alfalfa. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Zhili, and Huiling Ma. 2026. "Selection of High-Yield Varieties (Lines) and Analysis on Molecular Regulation Mechanism About Yield Formation of Seeds in Alfalfa" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010108

APA StyleRen, Z., & Ma, H. (2026). Selection of High-Yield Varieties (Lines) and Analysis on Molecular Regulation Mechanism About Yield Formation of Seeds in Alfalfa. Agronomy, 16(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010108