1. Introduction

The desert locust,

Schistocerca gregaria (Forskål) (Orthoptera: Acrididae), is well known for destruction of crops and rangeland vegetation and for inflicting indirect costs, some of which are societal [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The pest’s ability to drastically alter its behavior (and some morphological and physiological characteristics), changing from a solitary existence during the recession phase to amassing in vast, highly mobile swarms in the gregarious phase, which can expand an already enormous “recession distribution” to a considerably larger “plague distribution” [

1,

2,

4,

5,

7,

8], complicates its management. In the wake of the 1986–1989 desert locust plague, which cost the international donor (i.e., aid agencies) community an estimated USD

$310 million [

2,

5,

8,

9], and after the banning of long-residual organochlorine pesticides (e.g., dieldrin) in the late 1980s, heightened attention has been focused on advancing desert locust management beyond a reactive defensive posture toward proactive and preventive strategies [

5,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The reactive approach is taken while desert locust upsurges and plagues are already underway, most often due to unpreparedness [

7]. Proaction, on the other hand, is an intermediate strategy that is taken to quell population dynamics during outbreaks, before upsurge or plague status is reached [

7]. Prevention occurs sufficiently early to avert outbreaks, hence preventing any further development into upsurges or plagues [

7].

In fact, a preventive strategy has been envisaged for a very long time. Following the elucidation of phase theory (whereby the pest can change between solitary and gregarious morphologies and behaviors depending on population density) by Uvarov [

13] and the location of major desert locust breeding areas in which outbreaks tend to originate, the Fifth International Locust Conference, held in Brussels, 1938, promulgated the need for international coordination as well as the possibility of developing a preventive strategy against swarm formation [

14]. Since that time, notable scientific and technical progress has been achieved in realms that are essential to improving desert locust surveillance (during recessions and during episodes that involve swarming, i.e., outbreaks, upsurges, and plagues) methods and control tactics [

7,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Salient examples include integration of remote sensing imagery and computerized synthesis of multidisciplinary data for increasingly accurate forecasting; additionally, the establishment of communication networks facilitates reporting from the field and dissemination of information between desert locust-afflicted countries and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, headquartered in Rome, Italy, which plays an irreplaceable role at the international level in the coordination of monitoring and control activities against this pest [

20,

22]. Global positioning systems (GPS) permit highly accurate locust aggregation targeting [

20,

23,

24], regardless of remote terrain, and increased reliance on oil-based ultra-low volume (ULV) pesticide formulations [

25,

26] reduces the volume of chemicals that are stored, transported, and sprayed onto the environment [

7,

27,

28,

29]. Concurrently, the introduction of biopesticides as a potential key component in locust management programs constitutes a significant recent advancement, although their use remains limited at present [

30,

31]. Ongoing research includes investigation into the use of unmanned aerial vehicles [UAVs or drones] for possible surveillance and control purposes [

7,

32,

33,

34]. In parallel, efforts are expanding, especially toward the development and application of various modeling approaches to improve real-time location of desert locust populations [

35], forecast migration patterns [

36], and assess the potential impact of climate change on the frequency and severity of outbreaks and invasions [

37]. In the early 1990s, and following the 1986–1989 plague, the FAO initiated its Emergency Prevention System Program for desert locust plague prevention [EMPRES-DL] in the central region of the desert locust’s recession distribution (composed of Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen), and that was later augmented by expanding EMPRES to include a West and Northwest Africa component [

7]. This initiative was designed to shift from costly and often late emergency responses to desert locust plagues toward a proactive, coordinated strategy. In recent years, early intervention, or proactive control efforts [

5,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12,

38] has, on several occasions, successfully eliminated desert locust populations before they could form swarms [

39,

40], thereby contributing to a reduction in the frequency of large-scale invasions. Over the past 60 yr, the interval between major desert locust episodes has steadily increased from just a few years during the 1960s to ≈10 yr by 1990, and more recently, ≈15 yr during the past three decades [

7].

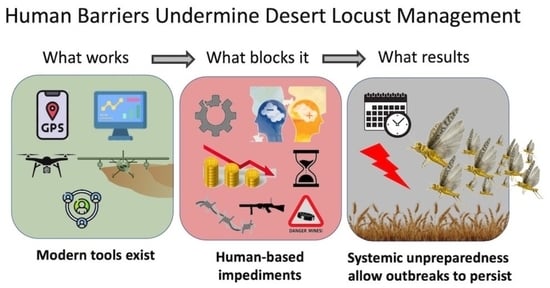

Due to its inherent complexity, desert locust management during swarming episodes is both resource- and labor-intensive [

6,

25]. Such complexity can be associated with diverse challenges that confront efficient management. While it is important to recognize and address technologically- and organizationally-based obstacles in order to eventually and sustainably develop the means for long-term, conceivably permanent, management of desert locust populations, human-based societal and financial challenges must also be identified and resolved [

6,

41,

42,

43,

44]. In spite of technological advancements aimed at minimizing the incidence of major desert locust episodes, the problem of serious upsurges and plagues has continued, and this condition will likely persist until extant nontechnical obstacles are mitigated or removed [

43]. Although it might be difficult to admit, intrinsic challenges that must be overcome before desert locusts can truly be managed originate within our own species. It is also possible that proactive desert locust control can be realized at the present state of technology if it were not for human-based impediments. While impediments of human origin that involve insecurity [

45,

46], political frictions, funding exigencies, weak lines of communication, inattention, and personnel issues have been reported [

5,

7], they have not been the main foci of stakeholders’ attention. Baraka et al. [

25] conducted a survey among 900 respondents from 30 counties in Kenya that were affected by desert locusts during the 2019–2021 control campaign. Although technological and geographical challenges caused 15% and 16% of the hindrances to control efforts (total 31%), respectively, human resources, coordination, financial limitations, political obstacles, and sociocultural issues hindered efforts by 17%, 16%, 13%, 12%, and 12%, respectively. Hence, human-based impediments in Kenya amounted to 70% of the sum of challenges [

25]. The purpose of this article is to recognize such societal and financial human-based obstacles, occasionally drawing from personal observations and experiences of the authors after >25 yr of working on desert locusts from bilateral, multilateral, and afflicted country perspectives. Although some human-based impediments are of greater magnitude and pervasiveness than others, each hinders proactive control and forethought of even more progressive strategies, involving increasingly early intervention for maintaining desert locusts in their recession phase indefinitely by averting outbreaks altogether (true desert locust episode prevention). Human-based impediments are examined in order to raise awareness of them and to broaden perspectives while considering the multitudinous facets inherent to desert locust management. Suggesting and developing specific solutions for human-based constraints will require dedicated study.

2. Insecurity

Nearly all of the countries where major desert locust recession breeding areas exist [

1,

47] are afflicted by insecurity [

45,

46]. Insecurity is a term that encompasses civil and international wars, rebellions, banditry, terrorism, and nonexploded ordnance, such as land mines [

45,

46]. Insecure conditions frequently overlap, or envelop, desert locust breeding areas, occluding access to them for ground and aerial surveillance and control operations. Lethal assaults against desert locust personnel over the last 30 years have been reported from Western Sahara to eastern Ethiopia [

45,

46]. The study of Kenya’s response during the 2019–2021 desert locust episode that heavily infested the country revealed that 75.6% of survey respondents felt insecurity was a significant constraint to desert locust management (in Kenya, mostly due to banditry) [

25]. Another study reported that insecurity deters surveillance and control operations and permits breeding to occur unchecked so outbreaks can grow into upsurges and reach plague status [

48]. The same study suggested that even an adequately funded desert locust management program can be negated if a mere 5% of its territory is inaccessible, that the proportion of plague years within a given time frame is greater when inaccessible areas are increased, and that multiple inaccessible areas heighten the risk of reaching plague status even more due to multiple “fronts” that require timely attention [

48].

As an illustration of the frequency of personal exposure to insecurity, one of the authors [AS] visited major battlefields in Eritrea immediately after the 30-yr war for independence from Ethiopia, had to be evacuated twice from Eritrea (once to Djibouti, the other time to Yemen) in one year due to war between Eritrea and Ethiopia, was bombed and strafed by Ethiopian MiG jets, and retained the services of nomadic Rashaida tribesmen as guides to avoid unmarked minefields while searching for desert locust activity. Flying low-altitude surveillance in a Desert Locust Control Organization for Eastern Africa (DLCO-EA) light aircraft over Ethiopia’s Ogaden Desert, near the Somali border, the plane was targeted by small arms fire likely, according to the pilot, from rebels or bandits. In addition, AS was directly exposed to, or in near proximity to, riots in Tunisia; numerous travel crackdowns; a terrorist bombing; an assassination of a high Palestine Liberation Organization officer; Yemeni clan shootouts; kidnapping of foreigners in Yemen; and rebellions in Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and Sudan, to name some. In a separate incident in 1991, in Niger, an encampment of scientists studying desert locusts in the Tamesna region [including one of the authors, ML] was attacked by armed assailants, resulting in one casualty [

49]. That same year, a widespread insurrection in Niger severely hindered desert locust monitoring and control operations through 1994 [

7].

While it is obvious that insecurity in desert locust breeding areas and places where surveillance and control operations should be conducted during episodes can obstruct operations [

25,

45,

46,

50], there are also deleterious indirect effects that hinder desert locust management. In terms of direct effects, insecurity can interfere with, or prevent, finding and controlling large-scale breeding, swarm development, swarms that move from elsewhere into insecure breeding areas, and swarms that move into other areas of insecurity outside the traditional breeding areas. Unlike nearly any other kind of insect control campaign, desert locust management is relatively frequently stymied by direct insecurity to the extent that it is regarded as a temporally chronic and geographically widespread problem [

2,

16,

46,

51].

Indirect impacts of insecurity can exert broad negative influences that manifest as debilitated government functions, diversion of attention away from agricultural threats, and competition for funds, equipment (especially vehicles), and personnel that might otherwise be deployed for agricultural purposes. Indirect insecurity occurs in two forms: active and inactive [

46]. Active indirect insecurity involves armed conflict (or civil disturbance) that is occurring concurrently with gregarious desert locust activity, but not in the same location [

46]. As a result of the ubiquity and variety of conflicts in many countries [

45,

46], active indirect insecurity is broad, dynamic, and persistent. Inactive indirect insecurity refers to lingering impacts after the insecure situation has abated, regardless of what part of the country the desert locust episode is manifest in. Long-lasting consequences include insufficient funds caused at least in part by prior inattention to maintaining operational capacity during periods of direct and active indirect insecurity, as well as by disabled and government-appropriated aircraft and ground vehicles, damaged infrastructure, and unmarked minefields. Simmering and dormant animosities between countries (e.g., Eritrea and Ethiopia when they are not actively fighting, or India and Pakistan) can negatively impinge upon surveillance and control operations [

7,

16,

46,

50] due to border tensions. Furthermore, ramifications of desert locust rangeland, pasture, and crop destruction include human population displacements and friction between farmers, nomads, and pastoralists over reduced resources, all compounded by the widespread, chronic, insidious, and inflammatory influences of indirect insecurity [

5,

6,

7].

Combatting desert locust episodes is accomplished by concentrated application of resources during limited windows of opportunity. Dwindling caches of resources undermine the likelihood of achieving sustainability; sustainability will be fundamental to maintaining the capacity for conducting proactive interventions and outbreak prevention. The resource-leaching impacts of insecurity are antithetical to maintaining preparedness for desert locust management. Unpreparedness in times of need can, in turn, instigate reliance on bilateral and multilateral international aid agencies and nongovernmental organizations for development and disaster assistance (in regard to controlling desert locust episodes).

Details regarding direct and indirect insecurity in selected desert locust-afflicted countries from 1986 through 2020 are described in separate published articles [

45,

46]. Selected examples of direct insecurity include (but are not limited to) obstructed control operations, 1986–1989, in northern Chad due to a long-standing border dispute with Libya [

1,

46], and civil war impaired operations through 2016 [

5,

52]. Eritrea’s 30-yr war for independence (1961–1991) from Ethiopia precluded desert locust control [

2,

5,

39,

45,

46], and, from then forward at least through 2000, unexploded land mines made travel in critically important desert locust breeding areas sufficiently dangerous to require use of aircraft instead of terrestrial vehicles [

45,

46,

53]. In 1999, Eritrea desert locust surveillance officers were detained near the contested Sudan border by the Sudan military, imprisoned, and tortured [

45,

46]. In 1992, a desert locust surveillance helicopter was shot down by rebels or bandits in the Ogaden Desert of eastern Ethiopia, killing all three persons aboard [

45,

46]. Desert locust surveillance team military escorts in Mali were killed by Tuareg rebels in 1994 [

45,

46], and operations in northern Mali were relatively frequently impeded through 2016 due to rebellions [

5,

52]. Somalia was mostly off-limits to desert locust control operations for decades as a result of long-term civil war [

45,

46]. Conflict in Western Sahara resulted in a United States C-130 being shot down by a Polisario guerrilla surface-to-air missile in 1988, killing the crew of five [

45,

46], and operations were not conducted in Western Sahara during the 1986–1989, 1992–1994, and 2003–2005 control campaigns [

2,

4,

5,

45,

46,

52]. Civil war and tribal or clan fighting have hindered control in Yemen during the 1986–1989, 1992–1994, and 2018–2021 desert locust episodes [

7,

45,

46]. Skirmishing in the Kashmir border region of India and Pakistan resulted in intensified tension along the entire border; some desert locust breeding areas on the border, south of Kashmir, were not fully controlled as a result [

29]. During those times, in one or more years, 10 of 13 major desert locust breeding areas had been the sites of direct insecurity, and indirect insecurity was even more widespread and persistent [

46]. Attempts to create regional and cross-border anti-locust “strike forces” were discontinued, or they struggled to operate due to lack of funds and aircraft maintenance (e.g., DLCO-EA) [

46].

3. Political Constraints

Often vague, intangible, unquantifiable, and difficult to characterize, political impediments to desert locust control are diverse and can slow processes within afflicted country ministries and the international aid community and between any stakeholders at local, national, and international levels and scales. Consequences can occur from negative effects on available funding, land use patterns, security, attention to research, information exchange, regional cohesion among countries, and bilateral and multilateral cooperation. On at least one occasion, a desert locust-afflicted country government ordered stocks of an entomopathogenic biopesticide (supplied by an international donor country) to be incinerated, fearing it might actually be for biological warfare [

39]. Although some political constraints have been reported in the scientific literature [

6,

7,

39,

51], the topic is generally not broached at international desert locust meetings and conferences due to the concentration on technical and programmatic issues and current locust events, and because political concerns can arouse sensitivities that might be perceived as being divisive. By 2001, Lecoq [

51] reported that desert locust control had become more dependent upon sagacious political and institutional choices than on technological and scientific advances. Lockwood and Sardo [

54] indicated that barriers to desert locust management were chiefly political, in addition to economic. Instances illustrative of disparate political interferences that challenge progress include deliberate and inadvertent failures of a country to exert desert locust swarm control before the pests fly into neighboring countries, shifting the onus of management responsibility to others [

4,

5,

6,

7,

55].

One of the authors [AS], while representing an international aid agency, observed and experienced the corrosive effects of national chauvinism between donor countries (carried out by individuals and not necessarily in accordance with national policies) that appeared to have harkened back in time to persistent medieval rivalries and historical colonialism rather than on contemporary, and seemingly more relevant, circumstances. Similarly, animosities between some international aid agency representatives and desert locust-afflicted country representatives arose from intentional and inadvertent expressions of racist attitudes, former colonial dominions, dismissal of the severity of desert locust impacts on human populations in afflicted countries, “territoriality” regarding traditional expertise on the topic of desert locusts, bilateral economic sanctions (e.g., some countries supplying international aid imposed economic sanctions against Libya and Sudan), and cultural, economic, and academic elitism. Conversely, the same author [AS] also witnessed desert locust-afflicted country representatives disparaging international aid agencies in adversarial public contexts. While the United Nations is intended to be a venue for capitalizing upon avenues for cooperation, unity, world peace, and prosperity, some national representatives at international meetings on desert locust issues revealed less than collegial viewpoints and eccentricities. Individually, each instance of politically based friction might appear insignificant, possibly unable to perceptibly alter overarching progress, but they collectively act as a brake against the likelihood of collaborative achievements in the realm of desert locust management.

A study conducted after a major desert locust episode in Kenya revealed that 50.5% of Kenyan control campaign respondents felt that political influence complicated efforts to manage the pest [

25]. This included Kenyan desert locust control officers being detained at international borders, which delayed aerial surveillance [

25]. For an insect that can fly 16–19 km in an hour [

56], such delays can result in losing track of highly mobile swarms. This provides more time for swarms to destroy crops, intensifying threats to food security [

25]. Lecoq [

22] indicated that the longer we wait to conduct control operations, the more the problem is exacerbated while challenges to solve it increase exponentially. Due to the relatively large number of countries involved, the need for efficient international cooperation is obviated [

22]. Furthermore, individual countries and groups of countries cannot, without wider international coordination, effectively manage significant desert locust episodes [

29]. In a similar vein, after sixteen meetings involving locust control officers from India, Pakistan, and Iran during 2020, little was improved regarding coordination of control efforts among the countries [

25]. Early intervention in individual countries will largely depend upon the willingness and capacity of desert locust-afflicted nations to disseminate, receive, and appropriately use information throughout the recession distribution [

29].

4. Dogma

Many scientific and technological advances are sometimes impeded by individuals who resist change or hold intractable points of view. Presented herein are two illustrative cases exemplifying this phenomenon.

Before the mid-1980s, desert locust control was conducted using long-residual, broad-spectrum insecticides that, after being deemed environmentally deleterious, were banned from further use in control campaigns during the late 1980s [

2,

7,

57]. Those long-residual chemicals were sprayed on foliage in breeding areas to kill desert locust nymphs as they fed on the insecticide-treated vegetation. The tactic, known as barrier spraying, was employed for several decades and did not require consistent human presence to be effective [

58,

59]. Since the late 1980s, shorter-residual and usually more selective insecticides have been used (mostly organophosphates and pyrethroids, although other classes of insecticides have also been applied). Such insecticides are primarily sprayed directly onto locust targets, requiring precision applications and the ability to operate within limited temporal windows of opportunity, often in remote, rugged, and contested terrain. The aim, after experiencing repeated reactive campaigns against desert locust upsurges and plagues, is to avert the development of full-blown plagues by intervening proactively during the initial, less immediately formidable and agriculturally threatening outbreak stage [

5,

7,

21,

24]. While proactive intervention was demonstrated on the Red Sea coast of Sudan against coalescing swarms [

39], and it is, in principle, an effective strategy for averting plague status [

5], there exists plenty of latitude to fail by missing optimal windows of opportunity, as occurred recently, 2018–2021 [

7]. Upon parsing the commonly used and rather vague term “prevention” into two subcategories, (1) proaction against ongoing outbreaks and (2) prevention of outbreaks, some desert locust international aid agency representatives have expressed confusion over the useful distinction, and some even espoused abandoning proactive control efforts [

60,

61]. The only recourse, then, would be a return to disaster-prone reactive campaigns. Notions of eschewing proaction and dogmatic failure to distinguish between proaction and true prevention are not in alignment with the FAO’s Emergency Prevention System (desert locust component) [

22], created at the demand of the same international aid agencies. Such dogma seems rooted in territoriality (i.e., professional and nationalistic jealousy); hence, it is politically linked. In order to expedite progress, the stakeholder community must arrive at operational consensus independent of pernicious dogmas that stymie concepts at their inception.

Another example of obstructive dogma has been a persistent argument by a few international aid agency representatives (no one from desert locust-afflicted countries) that desert locust control efforts are not necessary because desert locust episodes are not sufficiently impactful [

22]. Lecoq [

22] has indicated that studies aimed at assessing desert locust episode impacts have been too academic, limited in scope, or subjective for generating accurate assessments. Some view the approach taken by certain international aid agency representatives, who downplay the damage inflicted by desert locusts, to be disappointing [

22]. While attempting to characterize the economics of desert locust control is needed, it has been controversial. Regrettably, the longer the question of justifying desert locust control is unresolved, the greater damage will occur to aid agency perceptions, whose donations of finances and material are necessary for establishing sustainable desert locust management [

22]. Impact assessments should therefore encompass the entire spectrum of economic, environmental, political, safety, and social issues [

22]. While recent advances have contributed to a more nuanced understanding of these impacts [

62,

63,

64], continued and concerted efforts remain essential.

5. Insufficient Funding

Consistent long-term management of desert locusts that maintains preparedness for sudden onset of swarming episodes requires stable, dependable funding. Although this is widely understood, it is difficult for desert locust-afflicted country governments to justify making significant funding commitments from limited budgets for such intermittent events [

65].

Underlying causes of insufficient funding are multifaceted and occur at many levels, hampering surveillance and control operations during recessions and episodes. Competing interests are inherent to desert locust-afflicted country governments, regional organizations, bilateral aid agencies, and multilateral development organizations (such as the FAO) [

37,

65]. Also, most desert locust-afflicted countries are relatively poor and dependent to varying extents on international aid. While some countries, such as Saudi Arabia, are financially well-endowed and not donor-dependent, other countries generally struggle with maintaining sufficient agricultural production even during desert locust recessions. Reserving resources on a contingency bases for desert locust control requirements under such economically constraining conditions is untenable, and research on desert locust management by individual afflicted country ministries is of comparatively low priority.

Among numerous other integral aspects of desert locust management that are weakened by insufficient funding, infrastructure is often poorly maintained or nonexistent in areas where surveillance and control must be conducted, particularly in the “traditional” breeding areas [

5]. As an example, the Shelshela area of Eritrea’s Red Sea coastal plain, one of the most prolific of all desert locust breeding areas, was, during the 1980s and early 1990s, inaccessible by road, requiring as much as five hours to reach after navigating ridges,

wadis (dry streambeds), dunes, gulches, and minefields in a four-wheel-drive vehicle. During the latter half of the 1990s, a gravel causeway road was built to connect the only paved road (between Asmara and Massawa) to a small town called Shieb, adjacent to the Shelshela area, shortening the journey to merely thirty minutes.

Chronic funding shortages diminished the availability of terrestrial vehicles, aircraft, maintenance and spare parts, radio equipment, fuel, safety gear, camping supplies, GPS units, training, and more [

2,

4,

5,

7,

65]. In order to increasingly centralize desert locust control and to defray costs incurred by individual countries, several regional desert locust control organizations were established to protect areas from northwest Africa to Africa’s Horn [

47,

48,

65]. All but one of them have since been disbanded largely from lack of member nation payments and inertia during desert locust recession years. DLCO-EA, composed of eight member nations, has survived, but it has been in arrears for decades, at times struggling to maintain its aircraft and to pay employee salaries. The organization was owed >USD

$10 million in membership fees, for example, in 2020 [

66]. There have been instances where the organization was unable to respond to desert locust episodes in a timely fashion and other instances where it failed to do so altogether [

25,

65,

66]. Cash-strapped conditions in most desert locust-afflicted countries and DLCO-EA have resulted in relatively heavy reliance on international donor country and FAO contributions [

67]. As another example, in many desert locust-afflicted countries during swarming episodes, equipment such as sprayers, radios, and terrestrial vehicles were not only in short supply, but they were also in disrepair, unsuitable, and impractical for use in some situations [

25,

29]. Constraints on equipment slowed desert locust control operations, allowing additional time for crops and pastures to be destroyed [

25].

In Kenya, participants in the study on constraints to desert locust control operations during the 2018–2021 episode, 74.7% of the respondents indicated that funding shortfalls constituted a major impediment [

25]. Scarcity of funds, compounded by misappropriations, retards responses to time-critical circumstances [

25]. Kenya, for one, had to obtain a World Bank loan to finance desert locust control [

25]. In the same study, 51.1% of the respondents felt that corruption played a significant role in reducing available funds [

25]. Throughout most of the desert locust distribution, most constraints, such as poor infrastructure, aircraft contract renewals, conducting surveillance during recession periods, maintaining vehicles, and training of personnel, were remedied through adequate provision of funding [

25].

Further compounding the problem of limited funding, sudden needs for rapid response midway through the fiscal year are unable to be addressed when national, state, and county governments cannot allocate already scarce funds for outbreak contingencies [

25]. The international aid community, however, has not been a bottomless source of funds. While natural disasters, such as earthquakes, typhoons, and tsunamis, are viewed as warranting disaster relief aid whenever they inflict serious human injury and property damage, desert locust episodes have been perceived differently. There was a growing conviction that, since the late 1980s, the desert locust conundrum has been a chronic problem that is better rectified through development aid instead of through disaster relief. Debate occurred within many international aid agencies about how to proceed as the agencies diverted funds for other uses (e.g., competing disasters and development projects). The term “donor fatigue” was coined, implying that recurring disaster response support for desert locust plague control should not be assumed.

A clandestine meeting restricted to approximately seven international aid agency representatives [AS was one of them] occurred in the early 1990s. It was held in a rustic restaurant nestled deep in a forest near Wageningen, the Netherlands, and chaired by the Netherlands aid agency’s representative. It was unanimously decided that a letter would be drafted and signed by pertinent donor country governments, then it was delivered to the highest levels of the FAO in Rome. The letter essentially stated that desert locust plagues were a chronic problem and that international aid for desert locust control might shrink considerably unless a concerted effort was made to prevent plagues from occurring. The FAO subsequently established the EMPRES Program for desert locusts.

7. Inattention

Serious desert locust episodes have developed even in countries without widespread insecurity and without funding weaknesses. As a fairly recent example, in spite of Saudi Arabia’s resource availability, independence from international aid, and membership in EMPRES, a major desert locust outbreak grew unnoticed there. Heavy rainfall during the second half of 2018 in Saudi Arabia’s

Rub al-Khali [

7,

65], or Empty Quarter, suggested that special vigilance was needed in that remote area. Subsequent favorable breeding conditions supported three undiscovered, consecutive, increasingly populous generations of desert locusts [

7,

65]. By the year’s end, following their initial detection, swarms had become more widely distributed inside Saudi Arabia and also moved into Egypt, Eritrea, Sudan, and Yemen [

7]. Control operations in Yemen were hindered by armed conflict (rebellions and war with Saudi Arabia) [

7]. As the swarms continued to spread, entering Iran, Somalia, and Ethiopia, insecurity and unpreparedness created additional obstacles to surveillance and control operations, and the upsurge expanded east to India and south to Kenya and Tanzania [

7]. Ramifications of inattention to real-time events in Saudi Arabia’s

Rub al-Khali were enormous, lasting into 2021 [

7].

8. Personnel Issues

Human resource-based obstacles pertaining to desert locust control in afflicted countries can roughly be reduced to two issues: low coordination among and inadequate training of personnel. Weak coordination often leads to inefficient action [

5,

25,

46]. The survey-based study in Kenya determined that, during the 2018–2021 episode, 70.5%, 56.7%, and 52.7% of the respondents cited lack of clear leadership, weak supervision, and confusion regarding roles, respectively, as posing challenges during desert locust management efforts [

25]. The lengthy inactive recession periods, in particular, eventually erode institutional memory, trained manpower, and stocks of equipment and material [

25,

28,

44,

69,

70].

During recession periods, which can last a decade or more, trained human resources in desert locust-afflicted countries are promoted, transferred, retired, and rotated among positions, resulting in “institutional memory loss” (this also happens in international aid agencies). Institutional memory loss leads to the need for a certain amount of “reinventing the wheel” when major desert locust episodes occur. Loss of institutional memory and of trained personnel was identified by the FAO as a significant challenge to desert locust control operations [

5,

71]. In some instances, assignment of military and paramilitary personnel to desert locust control efforts is practiced due to shortages of trained Ministry of Agriculture agents [

2,

25]. The survey-based study in Kenya showed that 61.1% of the respondents cited limitations of knowledge and skills as having been an obstacle to Kenya’s efforts to combat the 2018–2021 episode, after several decades of desert locust inactivity there [

25]. Furthermore, 57.8% of the respondents felt that inadequate training of plant protection stakeholders presented obstacles [

25]. Because of such knowledge gaps, Kenya enlisted trainers from other countries to provide in-country training, which enhanced the Ministry of Agriculture’s resiliency for responding to the episode [

25]. It is important to point out that Kenya (like other countries), which does not host major desert locust breeding areas, is not one of the so-called “frontline countries”. Although Kenya is a member of the Desert Locust Control Committee, it appears to have, to a salient extent, overlooked the likelihood of being afflicted by desert locust swarms, such as it was during the 2018–2021 episode [

7]. Hence, Kenya, along with other countries, did not maintain necessary expertise and preparedness, which proved detrimental when the situation escalated following the failure of preventive operations in other countries where the episode originated.

9. Conclusions

Inadequate preparation for possible major desert locust episodes is fundamental to losing the initiative, and it is responsible for facilitating the genesis and magnification of the substantial episodes that occurred during 1986–1989, 1992–1994, 2003–2005, and 2018–2021 [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

39,

51,

55,

72,

73]. Unpreparedness results from some or all of numerous causes that include insecurity, low funding, unstable governments, corruption, armed conflict, political frictions, weak communication, and inefficient surveillance [

5,

7,

9,

39,

72] (

Table 1). Although crucially important, unpreparedness is listed last in this article because it is the ultimate result of the other six previously described impediment categories. Unpreparedness is problematic primarily because human and material resources have not been mobilized, or are unavailable, when desert locust episodes begin and grow into upsurges and full-blown plagues. Reliance upon the international aid community typically ensues. Because each international aid agency is usually a government bureaucracy, assessment of the ongoing situation and procurement of resources and their delivery require time while highly mobile desert locust swarms actively breed and fly across vast expanses of Africa and Asia, destroying crops and range grasses en route. Competing agricultural interests, such as protection of crops from routine pests, can diminish investment in sustainable desert locust management, particularly during long recession periods. During those relatively inactive times, resources become pooled with others, diverted for immediate uses, fall into disrepair, and become obsolete (e.g., over-aged pesticides). As an example illustrative of long desert locust recessions, Pakistan’s government, like Kenya’s, had not contended with serious desert locust activity for >27 yr until the 2018–2021 episode [

29].

A prominent instance of unpreparedness, the 1986–1989 desert locust plague originated along the Red Sea coast of Eritrea and Sudan. Because both of those countries were unprepared due to civil war, rebellion, lack of resources and funds, and initial phases of the plague, they were undetected, and after detection, they overwhelmed existing crop protection capabilities [

2,

5,

7]. Desert locust swarms bypassed national borders, moving into all of the unprepared Sahelian countries from Chad to the Cape Verde Islands. When swarms arrived in better-prepared northwestern African countries, control efforts were relatively, but not completely, effective. Regardless, once the plague had gained sufficient momentum, its eventual demise was more a consequence of weather than due to the reactive control strategy aimed at protecting crop production [

2,

7,

73].

The diverse and occasionally subtle human-based obstacles to developing and implementing desert locust management among several dozen afflicted countries on at least two continents (Africa and Asia) and across decades of fluctuating intensities are sufficiently complex in and of themselves. Those obstacles, however, are further compounded by swarm mobility and vast, rugged, and often perilous expanses, most of them uninhabited deserts, spanning Cape Verde to India, presenting challenges unlike those encountered while endeavoring to control any other insect pest. The sheer multitude and interconnectivity of physical and social impediments has necessitated global involvement such that stakeholders also involve international aid agencies, including, but not limited to, England, France, Norway, Sweden, the United States, and the Netherlands. Each aid agency is closely tied to its foreign ministry (or state department) to harmonize approaches to rendering assistance with national policies. While research and technology have made strides toward meeting some of the physical challenges and peripherally assisting with some human-based challenges, the latter present impediments that nevertheless remain largely unaddressed. Although some are mentioned, typically in passing as though they are beyond possible rectification or circumvention, those obstacles are usually not seriously considered. In comparison, technical aspects of desert locust control are the main foci of discussion and ameliorative efforts. Technical advances should certainly continue with vigor, but technological issues are no longer the most limiting factors. In order to achieve sustainability of desert locust management, a concept vaunted by most or all stakeholders, it will become necessary to shift, or at least share, concentrated effort on circumventing, mitigating, or overcoming human-based obstacles. To initiate processes devoted to that end and to make improvements, we must cease to regard such impediments as being intractable and, hence, tacitly acceptable.

10. Author’s Credentials

Allan Showler’s B.S. was earned in entomology and his M.S. in Plant Protection and Pest Management at the University of California at Davis; he also holds a Ph.D. in entomology from Louisiana State University (1987), with minors in experimental statistics and in nuclear science. He had the interesting fortune of working in bilateral and multilateral international aid agency contexts, as well as in desert locust-afflicted countries. Those experiences included working on desert locust disaster response for the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Office for Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA), on desert locust research projects for the Research and Development Bureau, and on locust control as the director of the African Emergency Locust/Grasshopper Assistance (AELGA) Project (USAID/Africa Bureau) for nine years in all, based in Washington, DC. During that time, he was involved with the control of other major pests, including the highly successful New World screwworm eradication program in Libya. For an additional four years, he headed the FAO’s EMPRES Program, posted in Asmara, Eritrea, his office located within the Eritrean Ministry of Agriculture there. Earlier in life, he served as an agricultural extension Peace Corps volunteer in Tunisia. Currently Allan Showler is a senior research entomologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, where he has worked almost exclusively on surveillance, ecology, behavior, and control of serious invasive pests that include cotton boll weevils, Mexican rice borers, red imported fire ants, and cattle fever ticks. In all, he has published more than 180 peer-reviewed scientific articles and book chapters. He speaks Arabic as well as a number of other languages, was married in Asmara to an Eritrean wife for 28 years, and his son was born in Sana’a, Yemen, during an evacuation prompted by the war between Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Michel Lecoq had dedicated over 50 years to the study of locust population dynamics, ecology, monitoring, and control, primarily within the framework of CIRAD (Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement) in Montpellier, France. From 1997 to 2010, he served as director of the research unit “Locust Ecology and Control”. Throughout his career, Michel Lecoq has worked extensively in tropical regions and has conducted field research in numerous countries affected by locust outbreaks. His work has significantly advanced the understanding of the ecology and population dynamics of several key locust and grasshopper species, including the desert locust, migratory locust, red locust, Mato Grosso locust, and Senegalese grasshopper. He has been a strong advocate for the development and implementation of preventive control strategies while also investigating the socio-economic and institutional barriers, particularly sociological and financial, that hinder effective locust management. A key contributor to the FAO’s EMPRES-DL program from 1997 to 2010, Michel Lecoq participated in numerous studies and expert missions that supported a major institutional overhaul of preventive locust control systems in West and North Africa. Michel Lecoq earned his Ph.D. in entomology from Paris-Saclay University in 1975. His research output includes 112 peer-reviewed scientific articles, 74 books or book chapters, and numerous technical reports, consultancy documents, and outreach publications. As a recognized expert on locusts, he has served as a consultant for the FAO on numerous occasions. He was president of the Orthopterists’ Society and received the prestigious D.C.F. Rentz Award in 2010 in recognition of a lifetime dedicated to the study of pest locusts and grasshoppers.