Pollution Assessment and Source Apportionment of Heavy Metals in Farmland Soil Under Different Land Use Types: A Case Study of Dehui City, Northeastern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

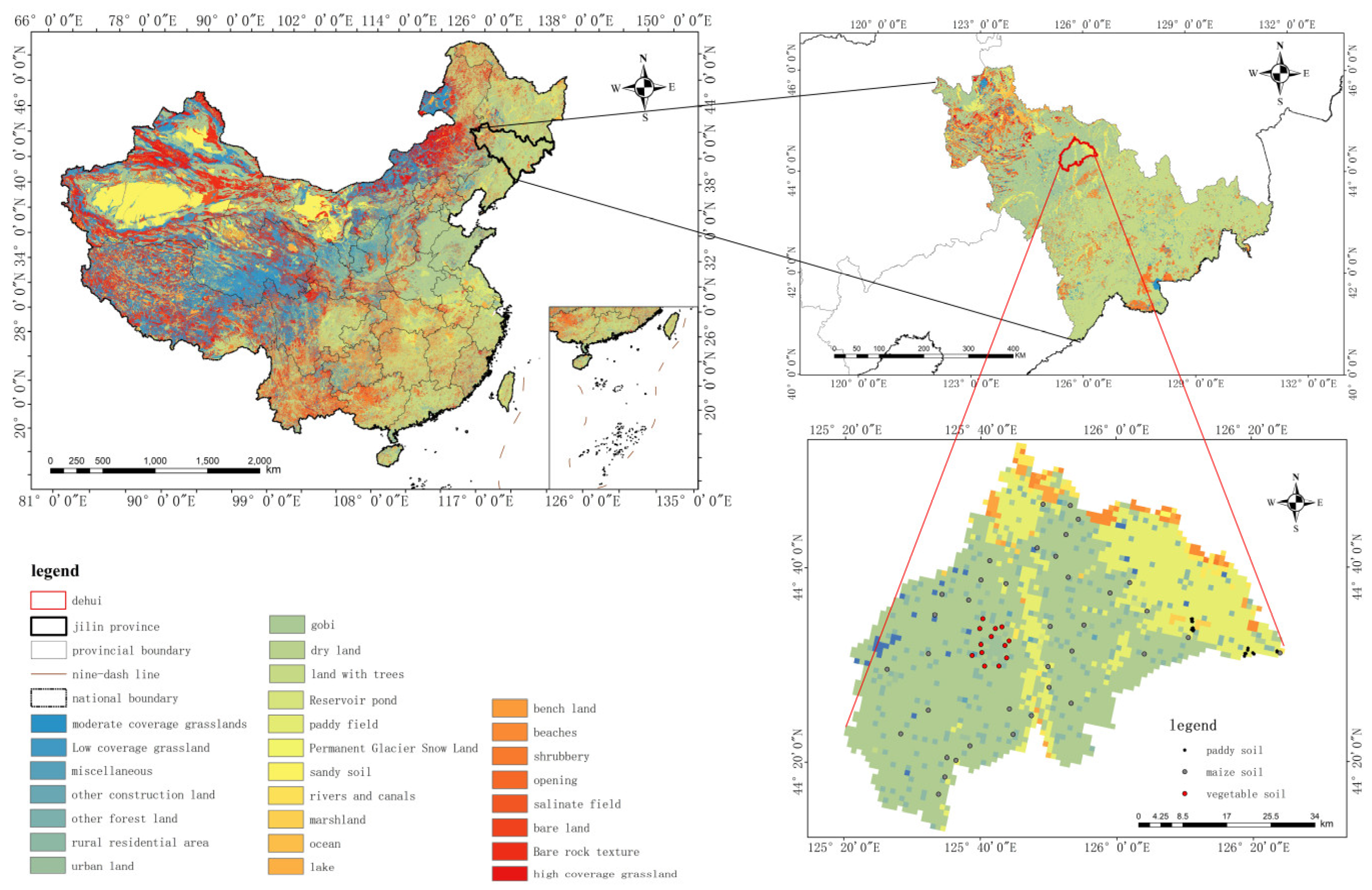

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Chemical Analysis and Quality Assurance/Quality Control

2.3. Pollution Assessment

2.3.1. Geo-Accumulation Index

2.3.2. Nemerow Integrated Pollution Index (NIPI)

2.3.3. Potential Ecological Risk Index (PERI)

2.4. Source Apportionment

2.4.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.4.2. Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

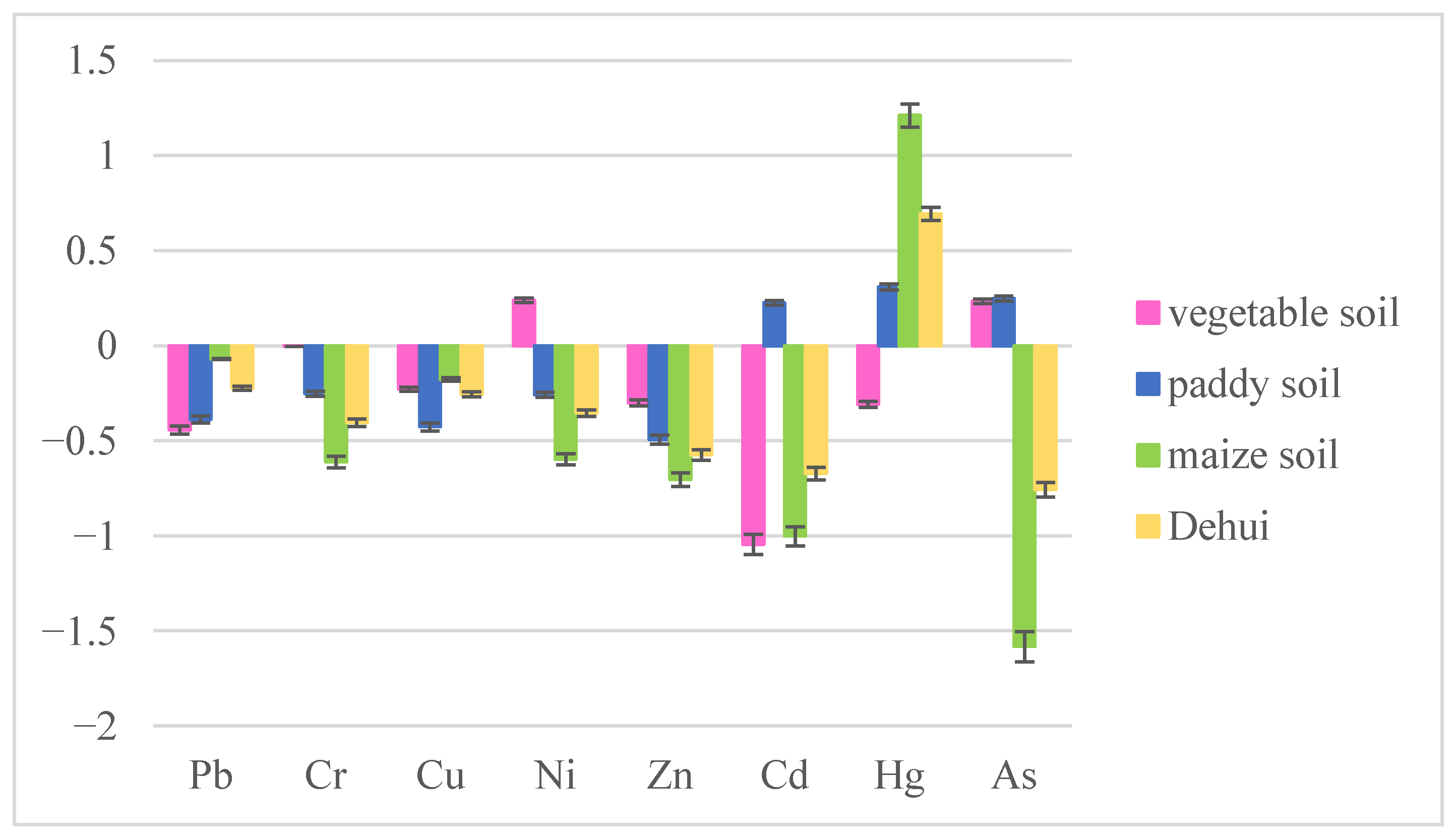

3.1. Statistical Characteristics of Heavy Metal Concentrations in Agricultural Soils of Dehui City

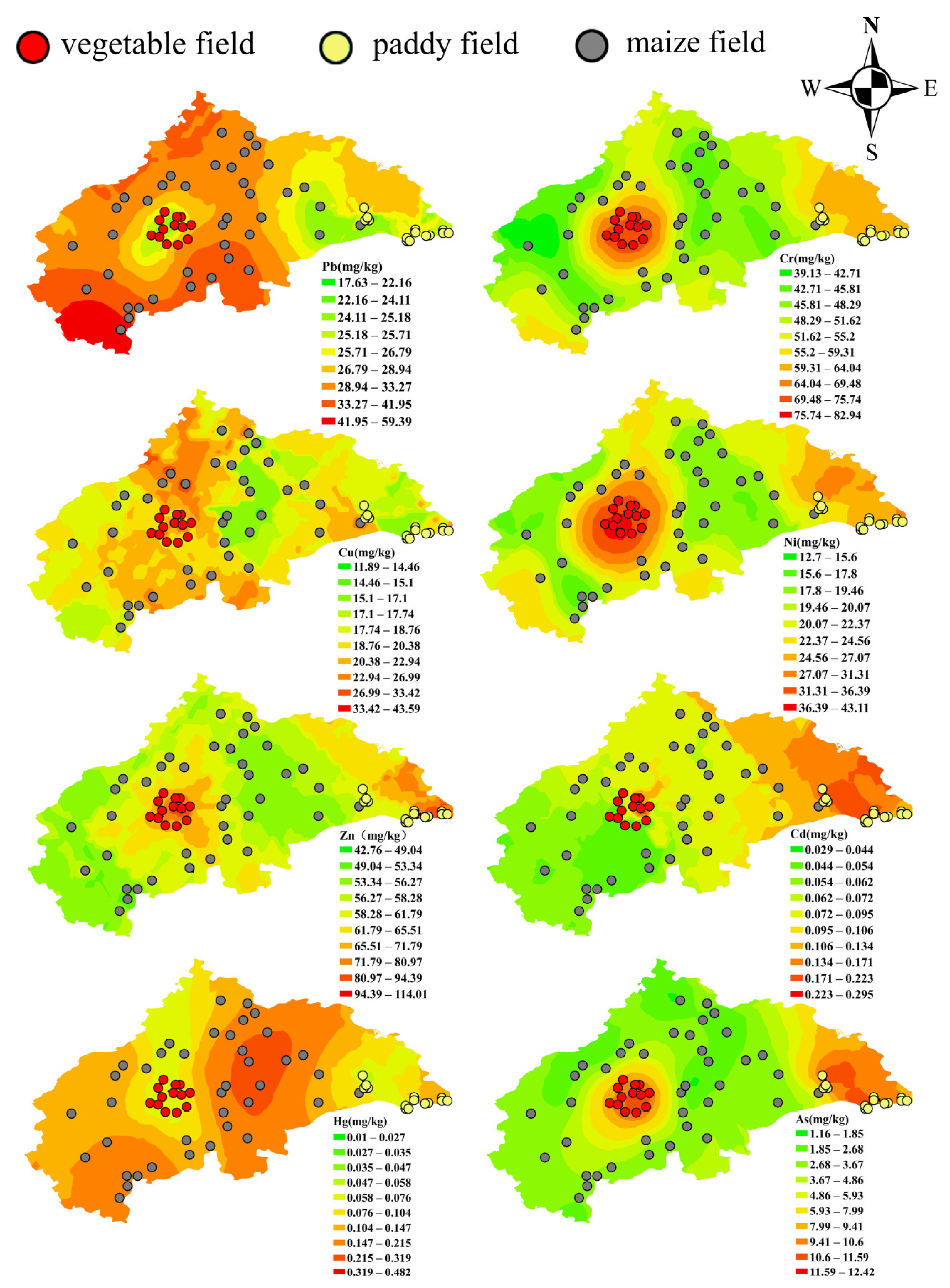

3.2. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils of Dehui City

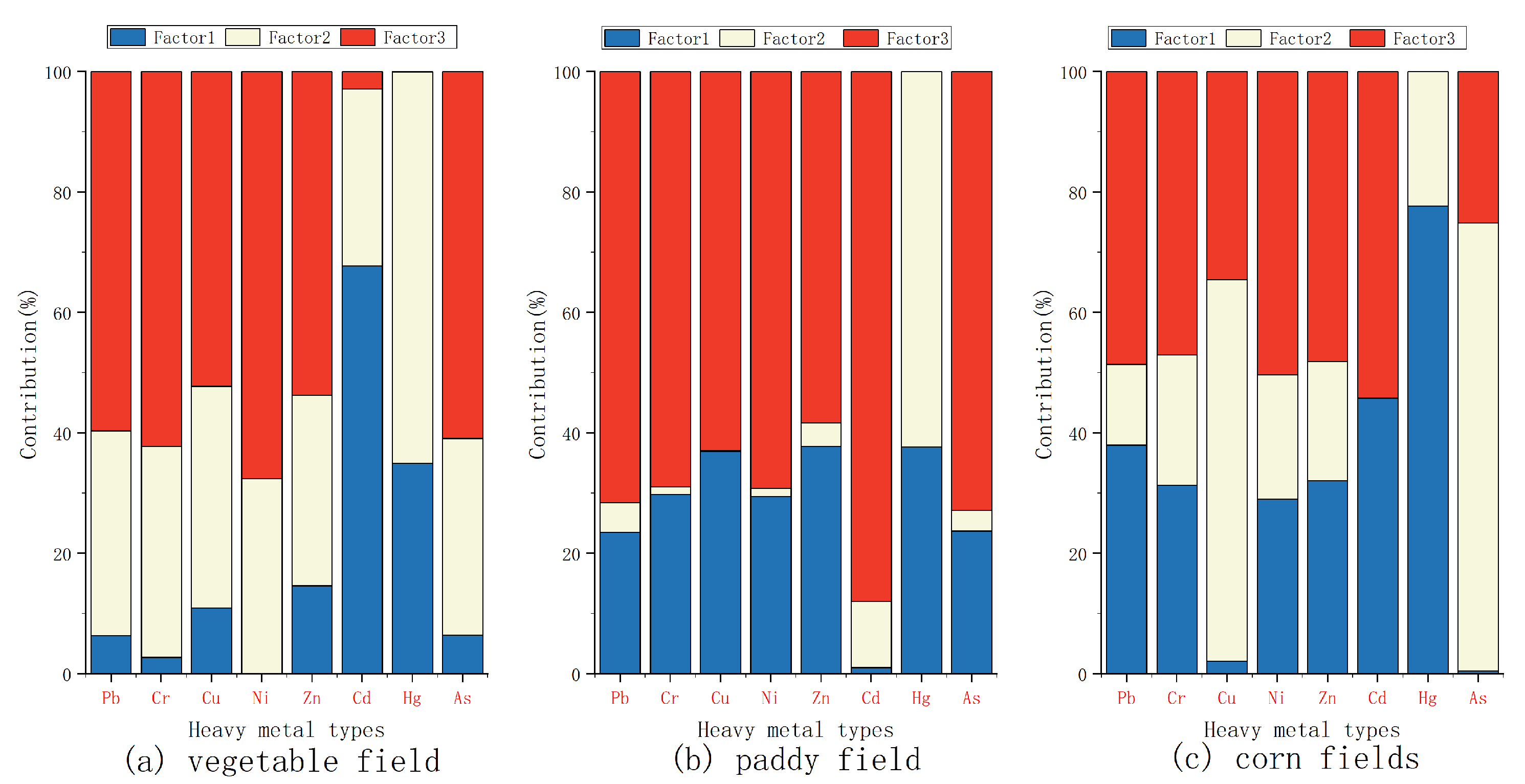

3.3. Source Analysis of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils of Dehui City

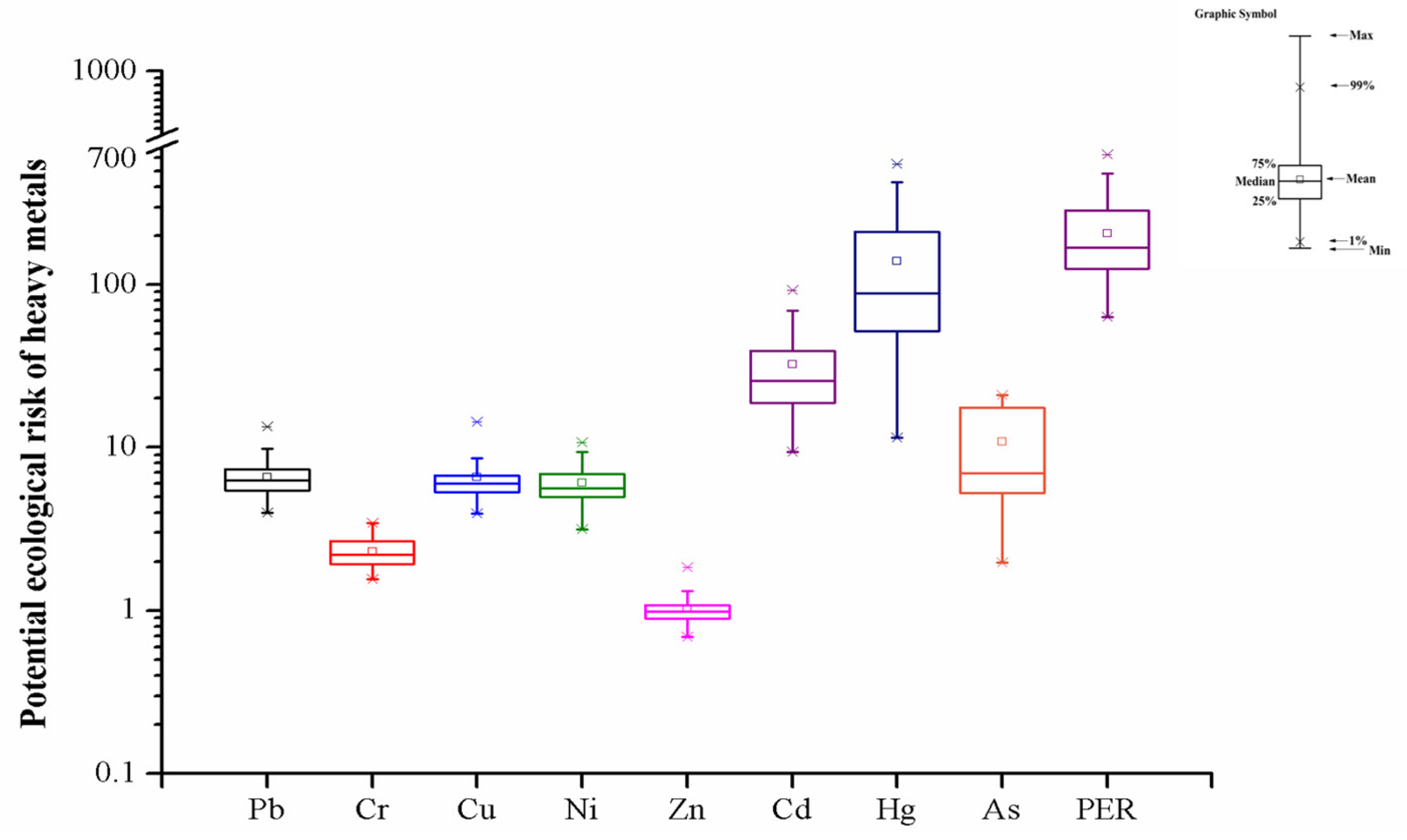

3.4. Pollution Indices and Potential Ecological Risk of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils of Dehui City

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO; ITPS. Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR)—Main Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils: Rome, Italy, 2015; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i5199e/i5199e.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Chen, R.S.; Sherbinin, A.D.; Ye, C.; Shi, G.Q. China’s Soil Pollution: Farms on the Frontline. Science 2014, 344, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.C.; Li, Z.G.; Liu, J.L.; Bi, X.Y.; Ning, Y.Q.; Yang, S.C.; Yang, X.J. Apportionment of sources of heavy metals to agricultural soils using isotope fingerprints and multivariate statistical analyses. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, T.Q.; Wu, C.X.; He, Z.L.; Japenga, J.; Deng, M.H.; Yang, X.E. An integrated approach to assess heavy metal source apportionment in peri-urban agricultural soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Fu, M.; Yang, J.Y.; Song, Y.W.; Fu, G.W.; Wang, H.B.; Lin, C.; Wang, Y. Spatial distribution characteristics, ecological risk assessment, and source analysis of heavy metal(loid)s in surface sediments of the nearshore area of Qionghai. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1491242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.W.; Chen, H.Y.; Hu, L.T.; Sun, J.C. Multimethod Analysis of Heavy Metal Pollution and Source Apportionment in a Southeastern Chinese Region. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.W.; Dong, X.Q.; Liu, J.J.; Yang, F.; Duan, W.; Xie, M.X. Characterization and source apportionment of heavy metal pollution in soil around red mud disposal sites using absolute principal component scores-multiple linear regression and positive matrix factorization models. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Li, S.Y.; Sun, X.Y.; Yang, S.B.; Li, J. Heavy metal contamination in green space soils of Beijing, China. Acta Agric. Scand. B Soil Plant Sci. 2018, 68, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N.; Qian, H.; Wang, H.K. Assessment of heavy metal (HM) contamination in agricultural soil lands in northern Telangana, India: An approach of spatial distribution and multivariate statistical analysis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.M.; Dai, W.; Gong, S.X.; Ma, Z.Y. Analysis of spatial variations and sources of heavy metals in farmland soils of Beijing suburbs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.L.; Li, R.N.; Huang, S.W.; Wang, H. Risk assessment of heavy metal accumulation in cucumber fruits and soil in a greenhouse system with long-term application of organic fertilizer and chemical fertilizer. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.J.; Yang, M.D.; Liao, K.; Wang, J.L.; Huang, Z.W.; Zeng, H.L.; Fang, H.Y.; Deng, H. Distribution, sources, and ecological risks of heavy metal contamination at the sediment-water interface in the Dongjiang Basin based on in situ high-resolution measurements. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 383, 126853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaman, R.; Peng, C.; Jiang, Z.C.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, Z.H.; Xiao, X.Y. Identifying sources and transport routes of heavy metals in soil with different land uses around a smelting site by GIS based PCA and PMF. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 823, 153759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Zhao, P.; Xiao, B.H.; Ali, M.U.; Xiao, P.W. Heavy metal pollution and source analysis of soils around abandoned Pb/Zn smelting sites: Environmental risks and fractionation analysis. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setu, S.; Strezov, V. Impacts of non-ferrous metal mining on soil heavy metal pollution and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 898, 178962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Hassan, F.U.; Toriman, M.E.; Ahmad, R.; Bashir, M.A.; Rehim, A.; Raza, Q.-U.-A.; Ta, G.C.; Abdul Halim, S.B. Spatial assessment and ecological risk evaluation of soil heavy metal contamination using multivariate statistical techniques. Catena 2025, 228, 109550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Hu, J. Soil heavy metal pollution and health risk assessment around Wangchun Industrial Park, Ningbo, China. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 2613–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.F.; Xu, Z.X.; Dong, B. Spatial Distribution, Leaching Characteristics, and Ecological and Health Risk Assessment of Potential Toxic Elements in a Typical Open-Pit Iron Mine Along the Yangzi River. Water 2024, 16, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Huang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.H.; Li, R.S.; Xia, L.F.; Fan, Y.M. Assessment of Soil-Heavy Metal Pollution and the Health Risks in a Mining Area from Southern Shaanxi Province, China. Toxics 2022, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.Q.; Wang, Y.Z.; Xie, J.F.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.E. Effects of soil properties and land use types on the bioaccessibility of Cd, Pb, Cr, and Cu in Dongguan City, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 104, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.H.; Sun, M.L.; Xu, N.; Sun, G.Y.; Zhao, M.C. Land use change from upland to paddy field in Mollisols drives soil aggregation and associated microbial communities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 146, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Song, B.; Han, G.; Zhao, H.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H. Effects of coastal wetland reclamation on soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and total phosphorus in China: A meta-analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3340–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Zhao, X.; Qin, W.; Jiao, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, M. Temporal impacts of dryland-to-paddy conversion on soil quality in the typical black soil region of China: Establishing the minimum data set. Catena 2023, 231, 107303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Miao, X.Y.; Ouyang, S.H. Soil heavy metal pollution trends for intensive vegetable production system in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, China (2000–2024) and human health implications. Environ. Res. 2025, 283, 122178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Feng, S.W.; Liang, J.L.; Jia, P.; Liao, B.; Shu, W.S.; Li, J.T.; Yi, X.Z. Heavy metal pollution in farmland soils surrounding mining areas in China and the response of soil microbial communities. Soil Secur. 2024, 16, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambhaneeya, S.M.; Garaniya, N.H.; Surve, V.H.; Deshmukh, S.P. Assessment of heavy metal contamination and accumulation in soil and leafy vegetables collected from industrial belt in Bharuch district, Gujarat. Vegetos 2024, 38, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Academy of Sciences. White Paper on Northeast Black Soil (2020); Chinese Academy of Sciences: Beijing, China, 2020. Available online: https://www.sgpjbg.com/baogao/77409.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Changchun Statistical Bureau. Changchun Statistical Yearbook 2023; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: http://tjj.changchun.gov.cn/ztlm/tjnj/202404/t20240424_3302053.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- HJ 491-2019; Soil and Sediment—Determination of Copper, Zinc, Lead, Nickel and Chromium—Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry. China Environment Publishing Group: Beijing, China, 2019. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/jcffbz/201905/t20190513_702667.shtml?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Deng, M.H.; Wu, S.F.; Japenga, J.; Li, T.Q.; Yang, X.E.; He, Z.L. A modified receptor model for source apportionment of heavy metal pollution in soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 354, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.X.; Li, S.Z. Study on Background Value of Soil Environment of the Jilin Province; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cui, Z.W.; Wang, Y.; Rui, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, Y.B. Contamination features and health risk of heavy metals in suburban vegetable soils, Yanbian, Northeast China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2018, 25, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 15618-2018; Soil Environmental Quality—Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land (Trial). China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/trhj/201807/t20180703_446029.shtml (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Hakanson, L. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control: A sedimentological approach. Water Res. 1980, 14, 975–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Gui, S.F.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.J.; Wang, C.Y.; Guo, W. Ecological risk assessment and source identification for heavy metals in surface sediment from the Liaohe River protected area, China. Chemosphere 2017, 175, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.B.; Cheng, Q.M.; Weindorf, D.C.; Yang, B.Y.; Gong, Z.B.; Yuan, Z.X. Multiple approaches for heavy metal contamination characterization and source identification of farmland soils in a metal mine impacted area. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 174, 106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Yan, M.; Ma, B.; Cao, R. Source apportionment of soil heavy metals based on multivariate statistical analysis and the PMF model: A case study of the Nanyang Basin, China. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 102, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, M.; Yang, L.S.; Wei, B.G.; Cao, Z.Q.; Yu, J.P.; Liao, X.Y. Plastic shed production systems: The migration of heavy metals from soil to vegetables and human health risk assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 215, 112106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.W.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, N.; Yu, R.; Xu, G.H.; Yu, Y. Spatial Distribution and Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Paddy Soils of Yongshuyu Irrigation Area from Songhua River Basin, Northeast China. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.L.; Yan, B.X.; Wang, L.X. Quantitative characteristics and source analysis of heavy metals in paddy soils in downstream of the Second Songhua River, Jilin Province. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 22, 2965–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.F.; Wu, Z.Q.; Luo, X.R.; Wen, M.L.; Huang, L.L.; Chen, B.; Zheng, C.J.; Zhu, C.; Liang, R. Pollution assessment and source analysis of heavy metals in acidic farmland of the Karst region in Southern China-A case study of Quanzhou County. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 123, 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Feng, K.; Li, Y.J.; Zhou, Y. Factorial Kriging analysis and sources of heavy metals in soils of different land-use types in the Yangtze River Delta of Eastern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 14957–14967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.-Z.; Gao, Z.D.; Li, K.M.; Zang, F. Pollution characteristics and probabilistic risk assessment of heavy metal(loid)s in agricultural soils across the Yellow River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Z.; Cai, L.M.; Wang, Q.S.; Hu, G.C.; Chen, L.G. A comprehensive exploration of risk assessment and source quantification of potentially toxic elements in road dust: A case study from a large Cu smelter in central China. Catena 2021, 196, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.N.; Cheng, H.F.; Tao, S. The Challenges and Solutions for Cadmium-contaminated Rice in China: A Critical Review. Environ. Int. 2016, 92–93, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.H.; Chen, S.Q.; Li, K.; Lei, M.; Ju, T.N.; Tian, L.Y. Determining the priority control sources of heavy metals in roadside soils in a typical industrial city of North China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 136347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.Z.; Chen, D.; Xiao, W.D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, S.P. Distribution characteristics and risk analysis of heavy metals in different types of pesticides. J. Pestic. Sci. 2023, 25, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, J.S.; Wang, Q.C.; Wang, Y. Assessment of heavy metal pollution in urban agricultural soils of Jilin City, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2015, 21, 1869–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.J.; Yang, L.Y.; Han, X.M.; Dai, J.R.; Pang, X.G.; Ren, M.Y.; Zhang, W. Distribution characteristics of heavy metals in surface soils from the western area of Nansi Lake, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramlan; Basir-Cyio, M.; Napitupulu, M.; Inoue, T.; Anshary, A.; Mahfudz; Isrun; Rusydi, M.; Golar; Sulbadana. Pollution and contamination level of Cu, Cd, and Hg heavy metals in soil and food crop. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.L.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Cheng, J.M.; Wang, X.F. Source analysis and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in farmland soils around heavy metal industry in Anxin County. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Er | Risk Level | PERI | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | Low | <150 | Low |

| 40 ≤ Er < 80 | Moderate | 150 ≤ PERI < 300 | Moderate |

| 80 ≤ Er < 160 | Considerable | 300 ≤ PERI < 600 | Considerable |

| 160 ≤ Er < 320 | High | ≥600 | High |

| ≥320 | Very high |

| Pb | Cr | Cu | Ni | Zn | Cd | Hg | As | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 29.24 | 55.81 | 19.82 | 24.38 | 63.25 | 0.103 | 0.123 | 6.47 |

| Range | 17.63–59.39 | 37.48–82.93 | 11.90–43.59 | 12.70–43.10 | 42.77–114.01 | 0.030–0.300 | 0.010–0.480 | 1.16–12.42 |

| CV a | 24.73% | 20.38% | 33.09% | 27.30% | 19.65% | 56.38% | 83.07% | 59.52% |

| BV b | 22.16 | 48.29 | 15.10 | 20.07 | 61.79 | 0.095 | 0.035 | 5.93 |

| Paddy soil c | 100 | 250 | 50 | 70 | 200 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 30 |

| Others c | 90 | 150 | - | - | - | 0.3 | 1.8 | 40 |

| Heavy Metals | Vegetable Field Soils | Paddy Soils | Maize Field Soils | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

| Pb | / | 0.899 | / | / | 0.771 | / | / | 0.846 |

| Cr | / | 0.710 | 0.558 | / | 0.852 | 0.892 | / | / |

| Cu | 0.930 | / | / | 0.820 | / | / | 0.790 | / |

| Ni | / | / | 0.949 | / | 0.858 | 0.897 | / | / |

| Zn | 0.912 | / | / | 0.922 | / | 0.878 | / | / |

| Cd | 0.744 | / | / | −0.667 | / | / | / | −0.689 |

| Hg | 0.654 | 0.547 | / | 0.759 | / | / | / | / |

| As | / | 0.923 | / | / | 0.740 | / | 0.919 | / |

| Eigenvalue | 2.84 | 2.73 | 1.58 | 2.72 | 2.71 | 2.95 | 1.63 | 1.23 |

| Total variance (%) | 35.48 | 34.10 | 19.79 | 33.94 | 33.86 | 36.92 | 20.33 | 15.37 |

| Cumulative variance (%) | 35.48 | 69.58 | 89.37 | 33.94 | 67.80 | 36.92 | 57.26 | 72.62 |

| Parameter | Vegetable Soil | Paddy Soil | Maize Soil | Dehui |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.40 |

| min | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| max | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.78 |

| median | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.37 |

| Pollution level | ||||

| Safe (NIPI < 0.7) | 92.31% | 95.00% | 100.00% | 97.26% |

| Precaution (0.7 ≤ NIPI < 1.0) | 7.69% | 5.00% | 0 | 2.74% |

| Slight pollution (1.0 ≤ NIPI < 2.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Cui, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Ma, J. Pollution Assessment and Source Apportionment of Heavy Metals in Farmland Soil Under Different Land Use Types: A Case Study of Dehui City, Northeastern China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122899

Xu L, Cui Z, Wang Y, Wang N, Ma J. Pollution Assessment and Source Apportionment of Heavy Metals in Farmland Soil Under Different Land Use Types: A Case Study of Dehui City, Northeastern China. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122899

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Linhao, Zhengwu Cui, Yang Wang, Nan Wang, and Jinpeng Ma. 2025. "Pollution Assessment and Source Apportionment of Heavy Metals in Farmland Soil Under Different Land Use Types: A Case Study of Dehui City, Northeastern China" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122899

APA StyleXu, L., Cui, Z., Wang, Y., Wang, N., & Ma, J. (2025). Pollution Assessment and Source Apportionment of Heavy Metals in Farmland Soil Under Different Land Use Types: A Case Study of Dehui City, Northeastern China. Agronomy, 15(12), 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122899