Identification of the Chalcone Synthase Gene Family: Revealing the Molecular Basis for Floral Colour Variation in Wild Aquilegia oxysepala in Northeast China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Identification of AoCHS Members

2.3. Sequence Feature Analysis

2.4. Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Analysis

2.5. Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR

2.6. Correlation Network Between AoCHS5 and TFs

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of AoCHSs

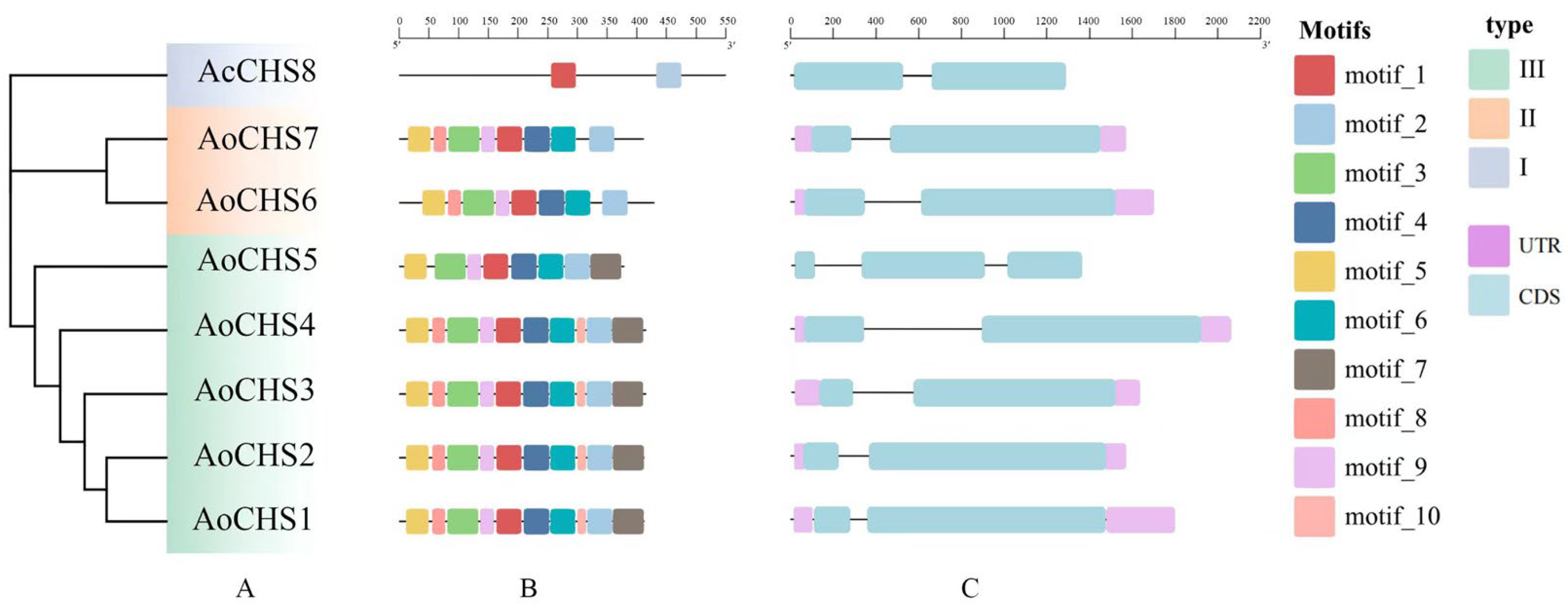

3.2. Analysis of Motifs and Gene Structure

3.3. Analysis of the Components of Cis-Acting Elementss

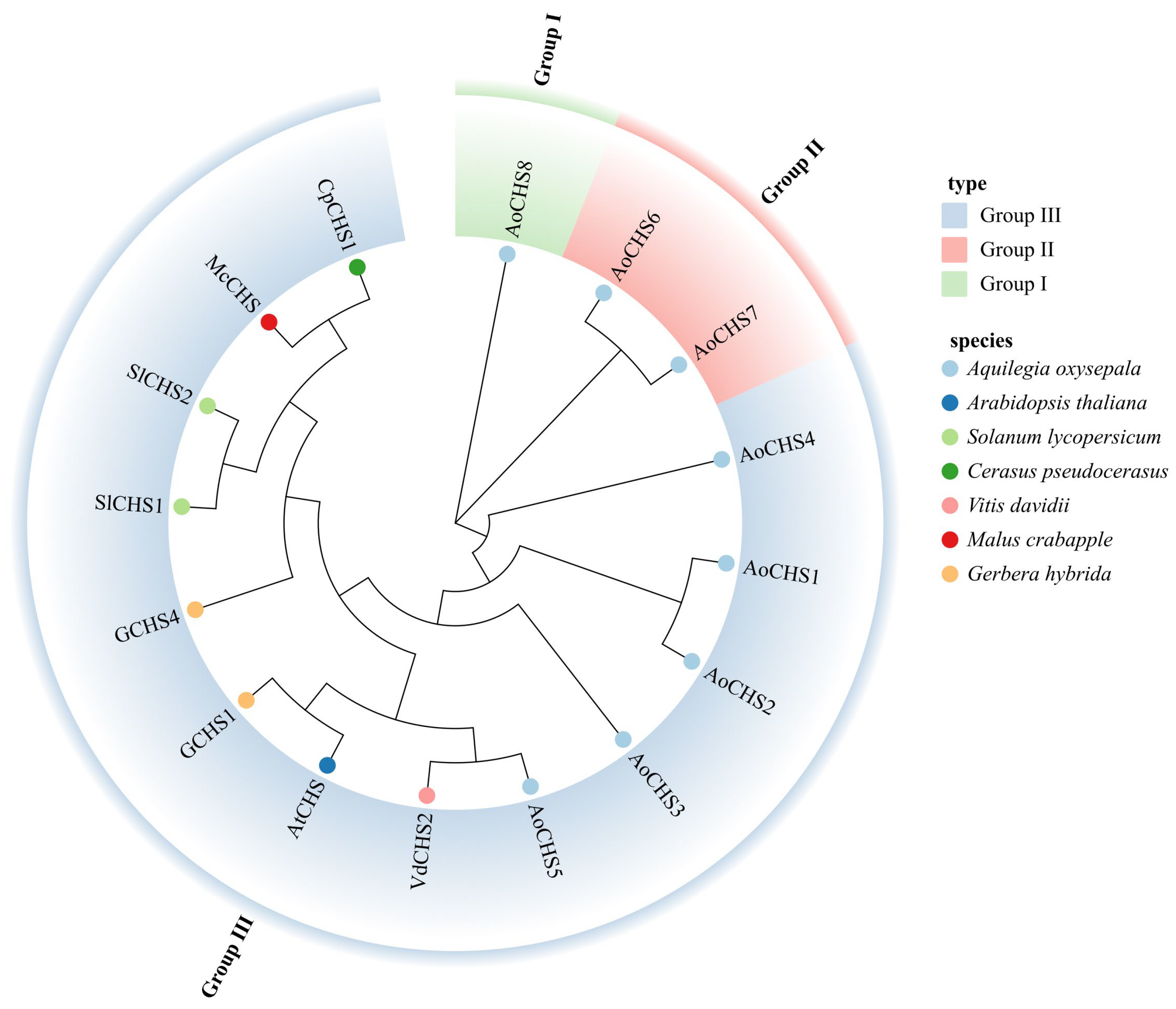

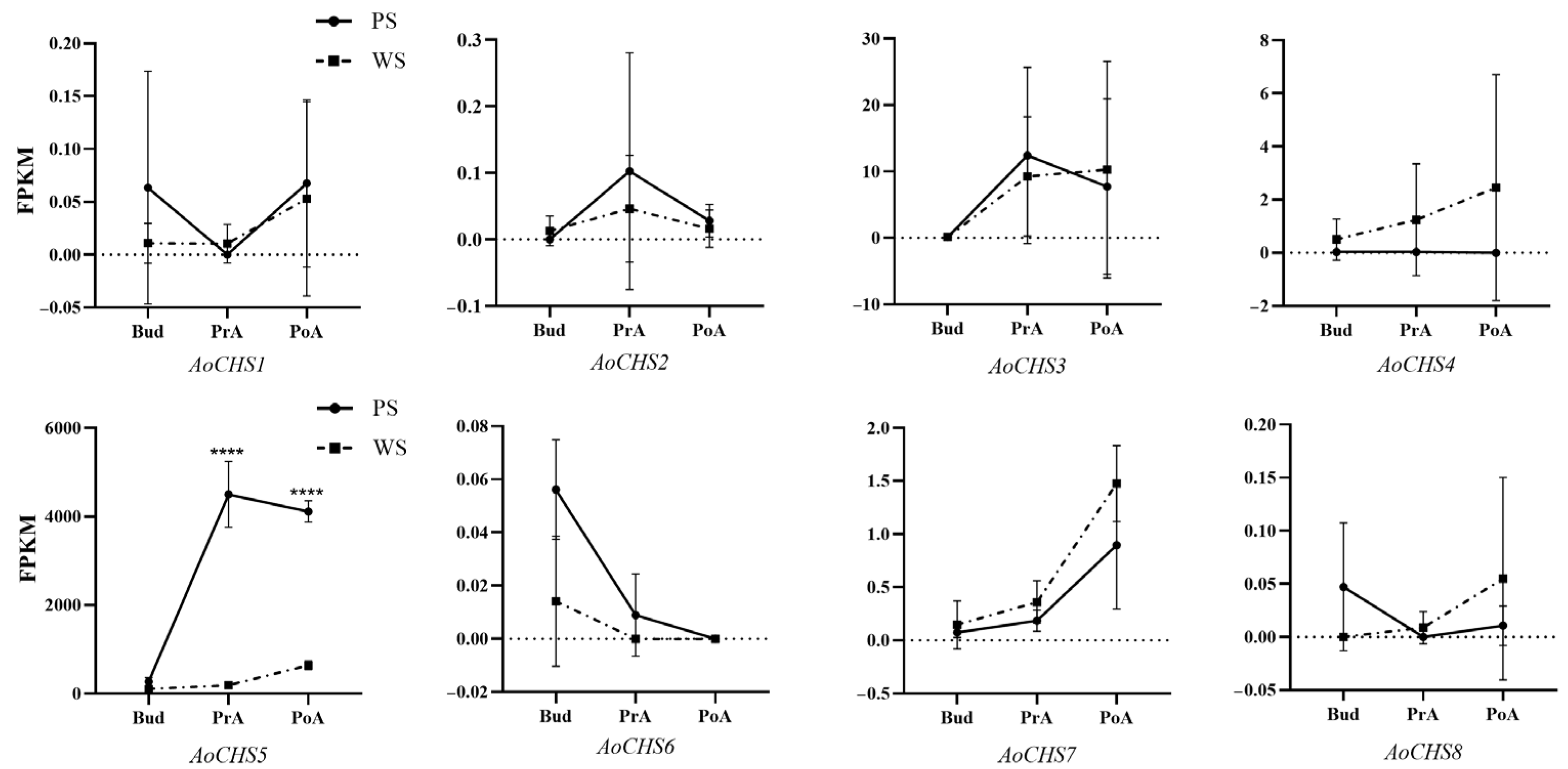

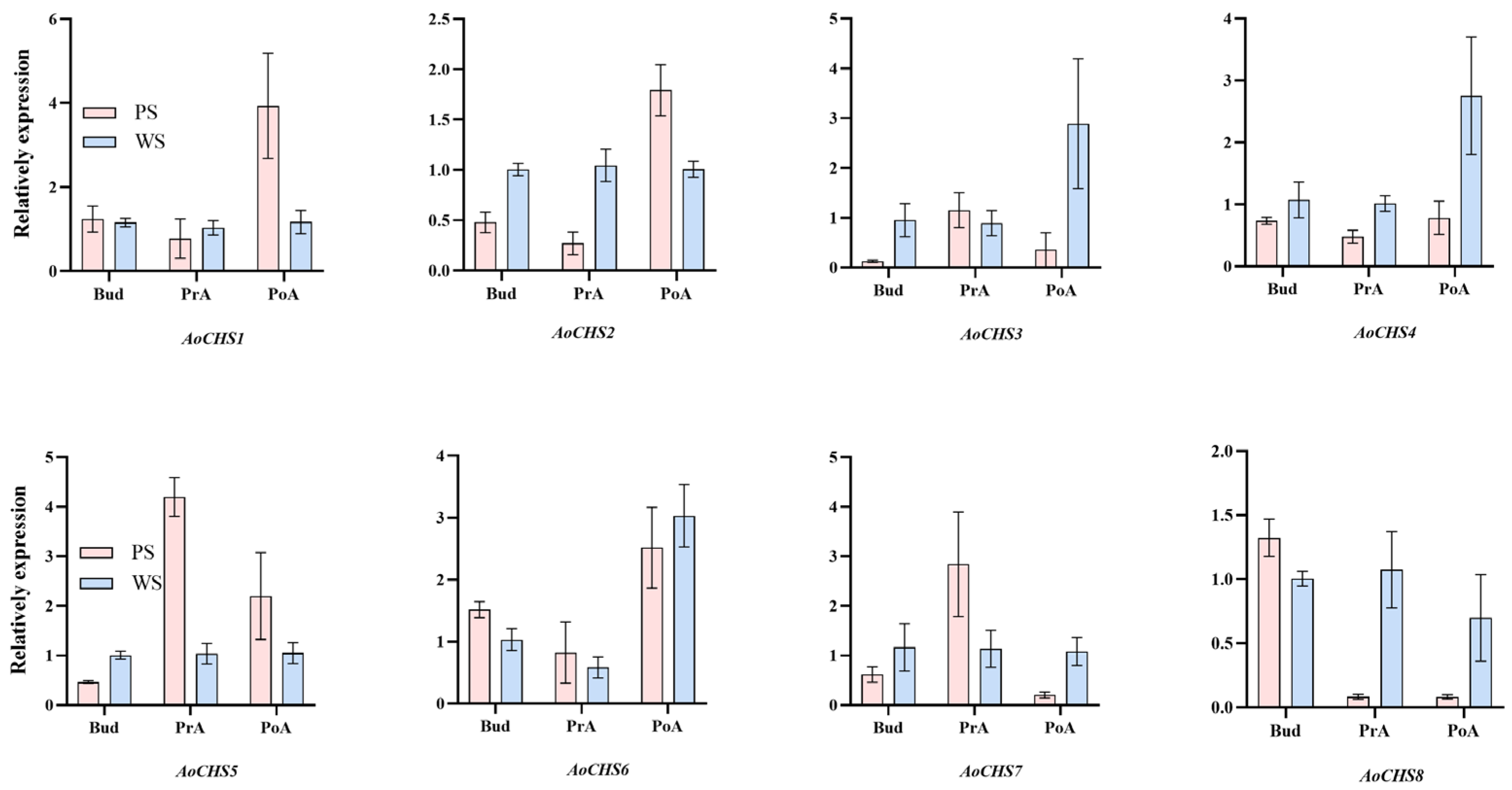

3.4. Phylogenetic and Expression Pattern Analysis

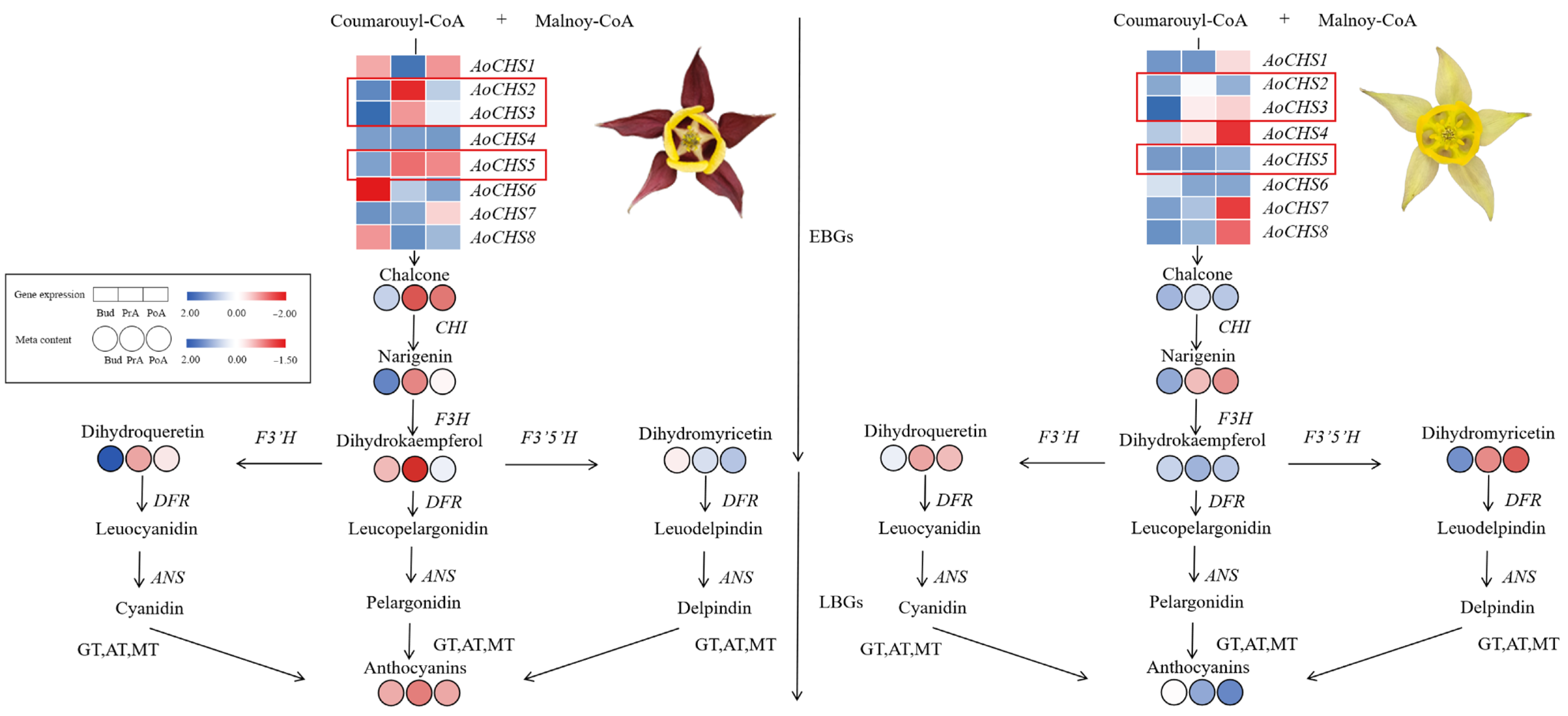

3.5. Potential Regulatory Mechanisms of AoCHS5

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, D.; Tao, J. Recent advances on the development and regulation of flower color in ornamental plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhao, D. Synergistic actions of 3 MYB transcription factors underpin blotch formation in tree peony. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 1869–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, Y.; Luo, L.; Pan, H.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q. Multiomics analysis reveals the mechanisms underlying the different floral colors and fragrances of Rosa hybrida cultivars. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2023, 195, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunschke, J.; Lunau, K.; Pyke, G.H.; Ren, Z.X.; Wang, H. Flower Color Evolution and the Evidence of Pollinator-Mediated Selection. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 617851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todesco, M.; Bercovich, N.; Kim, A.; Imerovski, I.; Owens, G.L.; Ruiz, Ó.D.; Holalu, S.V.; Madilao, L.L.; Jahani, M.; Légaré, J.S.; et al. Genetic basis and dual adaptive role of floral pigmentation in sunflowers. eLife 2022, 11, e72072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, R.; Che, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Metabolome and transcriptome profiling provide insights into green apple peel reveals light-and UV-B-responsive pathway in anthocyanins accumulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Luo, L.; He, H.; Liang, G.; Huang, H.; Huang, M. Transcriptomic Analysis of Flower Color Changes in Impatiens uliginosa in Response to Copper Stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, G.; Qiu, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, S.; Fang, W.; Chen, F.; Jiang, J. Transcriptome analysis reveals chrysanthemum flower discoloration under high-temperature stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1003635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Geng, Z.; Song, A.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, F. Functional identification of a flavone synthase and a flavonol synthase genes affecting flower color formation in Chrysanthemum morifolium. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2021, 166, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, W.; Wu, Q.; Dou, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Xing, S.; Yu, Y. Analysis of flower color diversity revealed the co-regulation of cyanidin and peonidin in the red petals coloration of Rosa rugosa. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2024, 216, 109126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, F.; Chen, Z. Integrated multi-omics reveals Li-miR828z-LiMYB114 regulatory module controlling anthocyanin biosynthesis during flower color development in Lagerstroemia indica. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 234, 121524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhu, Z.; Tan, C.; Gao, L.; Shen, W.; Wan, S.; Ge, X.; Chen, D.; Zhu, B. Fine-Mapping of OvANS: A Novel Gene Controlling White Flowers in Orychophragmus violaceus. Biology 2025, 14, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, S.; Wang, H.; Ming, F. The MYB transcription factor RcMYB1 plays a central role in rose anthocyanin biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, J.L.; Jez, J.M.; Bowman, M.E.; Dixon, R.A.; Noel, J.P. Structure of chalcone synthase and the molecular basis of plant polyketide biosynthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 1999, 6, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukma, D.; Handini, A.S.; Sudarsono, S. Isolation and characterization of chalcone synthase (CHS) gene from Phalaenopsis and Doritaenopsis orchids. Biodivers. J. Biol. Divers. 2020, 21, 5054–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittall, J.B.; Voelckel, C.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Hodges, S.A. Convergence, constraint and the role of gene expression during adaptive radiation: Floral anthocyanins in Aquilegia. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 4645–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, B.; Kramer, E.M. Virus-induced gene silencing as a tool for functional analyses in the emerging model plant Aquilegia (columbine, Ranunculaceae). Plant Methods 2007, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.B.; Tian, X.; Li, D.Z.; Guo, Z.H. Molecular composition and evolution of the chalcone synthase (CHS) gene family in five species of camellia (Theaceae). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2003, 45, 659. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Kang, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the chalcone synthase (CHS) gene family in Dendrobium catenatum. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.J.; Peng, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, A.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, F. CmBBX28-CmMYB9a Module Regulates Petal Anthocyanin Accumulation in Response to Light in Chrysanthemum. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 3750–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Sun, D.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; et al. AU-box E3 ubiquitin ligase CmPUB15 targets CmMYB73 to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to low temperatures in chrysanthemum. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoušek, J.; Kocábek, T.; Patzak, J.; Füssy, Z.; Procházková, J.; Heyerick, A. Combinatorial analysis of lupulin gland transcription factors from R2R3Myb, bHLH and WDR families indicates a complex regulation of chsH1 genes essential for prenylflavonoid biosynthesis in hop (Humulus lupulus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, E.M. Aquilegia: A New Model for Plant Development, Ecology, and Evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Zhu, Q.Q.; Sun, L.; Niu, C.Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Ren, Y. Petal ontogeny, floral structure, and pollination system of four Aquilegia species in Midwest China. Flora 2021, 286, 151987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Pandher, M.K.; Alcaraz Echeveste, A.Q.; Bravo, M.; Romo, R.K.; Ramirez, S.C. Comparative case study of evolutionary insights and floral complexity in key early-diverging eudicot Ranunculales models. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1486301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Si, W.; Ma, T.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, Y. Physiological and biochemical basis of flower coloration in Aquilegia oxysepala with a functional study of AoDFR08. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, S.; Chu, D.; Wang, X. Exploring the evolution of CHS gene family in plants. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1368358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Ciufo, S.; Domrachev, M.; Hotton, C.L.; Kannan, S.; Khovanskaya, R.; Leipe, D.; Mcveigh, R.; O’Neill, K.; Robbertse, B.; et al. NCBI Taxonomy: A comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database 2020, 2020, baaa062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söding, J. Protein homology detection by HMM–HMM comparison. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Mao, Z.; Gu, X.; Huang, S.; Xie, B. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY gene family in Cucumis sativus. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, M.; Chen, W.; Chai, Y.; Wang, W. Bioinformatic analysis of wheat defensin gene family and function verification of candidate genes. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1279502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvaud, S.; Gabella, C.; Lisacek, F.; Stockinger, H.; Ioannidis, V.; Durinx, C. Expasy, the Swiss Bioinformatics Resource Portal, as designed by its users. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W216–W227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, K.C.; Shen, H.B. Plant-mPLoc: A top-down strategy to augment the power for predicting plant protein subcellular localization. PLoS ONE 2021, 5, e11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Xia, R. A painless way to customize Circos plot: From data preparation to visualization using TBtools. Imeta 2022, 1, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbudak, M.A.; Filiz, E. Genome-wide investigation of proline transporter (ProT) gene family in tomato: Bioinformatics and expression analyses in response to drought stress. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2020, 157, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Mao, X.; Li, C. Phylogenetic, expression, and bioinformatic analysis of the ABC1 gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Sci. World J. 2013, 785070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cisacting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbreck, D.; Wilks, C.; Lamesch, P.; Berardini, T.Z.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Foerster, H.; Li, D.; Meyer, T.; Muller, R.; Ploetz, L.; et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): Gene structure and function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 36, D1009–D1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tamura, K.; Nei, M. MEGA: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software for microcomputers. Bioinformatics 1994, 10, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Shi, N.; Du, X.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Shen, H. Bioinformatics Analysis and Expression Profiling Under Abiotic Stress of the DREB Gene Family in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, F.; Rohlsen, D.; Bi, C.; Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Wei, S.; Ye, Q.; Yin, T.; Ye, N. Organellar genome assembly methods and comparative analysis of horticultural plants. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Bai, Y.; Chen, D.; Ma, T.; Si, W.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y. Integration of transcriptome and metabolome reveals key regulatory mechanisms affecting sepal color variation in Aquilegia oxysepala. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334, 113334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Dai, L. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Analysis of CHS Gene Family Members in Chrysanthemum nankingense. Genes 2022, 13, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ding, T.; Su, B.; Jiang, H. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression analysis of the chalcone synthase gene family in Chinese cabbage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Long, Y. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and expression and metabolic regulation of the maize CHS gene family under abiotic stress. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Jeridi, M.; Siddiqui, S.; Shah, A.Z.; Ali, S. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of the Chalcone Synthase gene family in Oryza sativa under Abiotic Stresses. Plant Stress 2023, 1, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Shen, W.; El Mohtar, C.A.; Zhao, X.; Gmitter, F.G., Jr. Functional study of CHS gene family members in citrus revealed a novel CHS gene affecting the production of flavonoids. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.K.; Schaal, B.A.; Chiou, Y.M.; Murakami, N.; Ge, X.J.; Huang, C.C.; Chiang, T.Y. Diverse selective modes among orthologs/paralogs of the chalcone synthase (Chs) gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana and its relative A. hallerissp. gemmifera. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 44, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biłas, R.; Szafran, K.; Hnatuszko-Konka, K.; Kononowicz, A.K. Cis-regulatory elements used to control gene expression in plants. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. (PCTOC) 2016, 127, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Garcia, C.M.; Finer, J.J. Identification and validation of promoters and cis-acting regulatory elements. Plant Sci. 2014, 217, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Xuan, X.; Tan, J.; Yu, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ramakrishnan, M. Analysis of the CHS Gene Family Reveals Its Functional Responses to Hormones, Salinity, and Drought Stress in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Plants 2025, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhai, Z.; Pu, J.; Liang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C. Two tandem R2R3 MYB transcription factor genes cooperatively regulate anthocyanin accumulation in potato tuber flesh. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchio, F.; Verweij, W.; Kroon, A.; Spelt, C.; Mol, J.; Koes, R. PH4 of Petunia is an R2R3 MYB protein that activates vacuolar acidification through interactions with basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factors of the anthocyanin pathway. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1274–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Chi, F.M.; Liu, H.D.; Zhang, H.J.; Song, Y. Single-molecule real-time and illumina sequencing to analyze transcriptional regulation of flavonoid synthesis in blueberry. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 754325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin-Wang, K.; Espley, R.V.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Allan, A.C. StMYB44 negatively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis at high temperatures in tuber flesh of potato. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 3809–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Derynck, M.R.; Li, X.; Telmer, P.; Marsolais, F.; Dhaubhadel, S. A single-repeat MYB transcription factor, GmMYB176, regulates CHS8 gene expression and affects isoflavonoid biosynthesis in soybean. Plant J. 2010, 62, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.P.; Luo, M.; Liu, X.Q.; Hao, L.Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, L.; Ma, L.Y. MYB-1 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in Magnolia wufengensis. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2024, 217, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Lv, A.; Wen, W.; Fan, N.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Zhou, P.; An, Y. MsMYB741 is involved in alfalfa resistance to aluminum stress by regulating flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 2022, 112, 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasil, V.; Marcotte, W.R., Jr.; Rosenkrans, L.; Cocciolone, S.M.; Vasil, I.K.; Quatrano, R.S.; McCarty, D.R. Overlap of Viviparous1 (VP1) and abscisic acid response elements in the Em promoter: G-box elements are sufficient but not necessary for VP1 transactivation. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.R.; Choi, J.L.; Costa, M.A.; An, G. Identification of G-box sequence as an essential element for methyl jasmonate response of potato proteinase inhibitor II promoter. Plant Physiol. 1992, 99, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Fu, J.; Jing, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, J. Phytochrome-interacting factors interact with the ABA receptors PYL8 and PYL9 to orchestrate ABA signaling in darkness. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Lefert, P.; Becker-Andre, M.; Schulz, W.; Hahlbrock, K.; Dangl, J.L. Functional architecture of the light-responsive chalcone synthase promoter from parsley. Plant Cell 1989, 1, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusnetsov, V.; Landsberger, M.; Meurer, J.; Oelmüller, R. The assembly of the CAAT-box binding complex at a photosynthesis gene promoter is regulated by light, cytokinin, and the stage of the plastids. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 36009–36014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Araki, S.; Matsunaga, S.; Itoh, T.; Nishihama, R.; Machida, Y.; Doonan, J.H.; Watanabe, A. G2/M-phase–specific transcription during the plant cell cycle is mediated by c-Myb–like transcription factors. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 1891–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Krol, A.; Mur, L.; Beld, M.; Mol, J.; Stuitje, A. Flavonoid genes in petunia: Addition of a limited number of gene copies may lead to a suppression of gene expression. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Bashandy, H.; Ainasoja, M.; Kontturi, J.; Pietiäinen, M.; Laitinen, R.A.; Albert, V.A.; Valkonen, J.P.; Elomaa, P.; Teeri, T.H. Functional diversification of duplicated chalcone synthase genes in anthocyanin biosynthesis of Gerbera hybrida. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 1469–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lai, G.; Lin, J.; Guo, A.; Yang, F.; Pan, R.; Che, J.; Lai, C. VdCHS2 Overexpression Enhances Anthocyanin Biosynthesis, Modulates the Composition Ratio, and Increases Antioxidant Activity in Vitis davidii Cells. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q.; Li, S.; Shang, C.; Wen, Z.; Cai, X.; Hong, Y.; Qiao, G. Genome-wide characterization of chalcone synthase genes in sweet cherry and functional characterization of CpCHS1 under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 989959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia, A.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.; Domínguez, E. CHS silencing suggests a negative cross-talk between wax and flavonoid pathways in tomato fruit cuticle. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014, 10, e1019979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.H.; Zheng, X.T.; Sun, B.Y.; Peng, C.L.; Chow, W.S. Over-expression of the CHS gene enhances resistance of Arabidopsis leaves to highlight. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 154, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, D.; Tian, J.; Zhang, J.; Song, T.; Yao, Y. A Malus crabapple chalcone synthase gene, McCHS, regulates red petal color and flavonoid biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 2017, 9, e110570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Kong, P.; Lu, K.; Adnan; Liu, M.; Ao, F.; Zhao, C.; et al. The biochemical and molecular investigation of flower color and scent sheds lights on further genetic modification of ornamental traits in Clivia miniata. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lian, X.; Ye, C.; Wang, L. Analysis of flower color variations at different developmental stages in two honeysuckle (Lonicera Japonica Thunb.) cultivars. HortScience 2019, 54, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chai, X.; Gao, B.; Deng, C.; Günther, C.; Wu, T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y. Multi-omics analysis reveals the mechanism of bHLH130 responding to low-nitrogen stress of apple rootstock. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 1305–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qiao, Q.; Zhao, K.; Zhai, W.; Zhang, F.; Dong, H.; Huang, X. PbWRKY18 promotes resistance against black spot disease by activation of the chalcone synthase gene PbCHS3 in pear. Plant Sci. 2024, 341, 112015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qu, P.; Hao, S.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wen, P.; Cheng, C. Characterization and Functional Analysis of Chalcone Synthase Genes in Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cheng, S.; Sun, X.; Gao, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, N. An R2R3 MYB transcription factor GhMYB5: Regulator of CHS expression and proanthocyanin synthesis in brown cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, D.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, T.; Yu, H.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, Y. Identification of the Chalcone Synthase Gene Family: Revealing the Molecular Basis for Floral Colour Variation in Wild Aquilegia oxysepala in Northeast China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122883

Chen D, Cheng Y, Ma T, Yu H, Bai Y, Zhou Y, Meng Y. Identification of the Chalcone Synthase Gene Family: Revealing the Molecular Basis for Floral Colour Variation in Wild Aquilegia oxysepala in Northeast China. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122883

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Dan, Yongli Cheng, Tingting Ma, Haihang Yu, Yun Bai, Yunwei Zhou, and Yuan Meng. 2025. "Identification of the Chalcone Synthase Gene Family: Revealing the Molecular Basis for Floral Colour Variation in Wild Aquilegia oxysepala in Northeast China" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122883

APA StyleChen, D., Cheng, Y., Ma, T., Yu, H., Bai, Y., Zhou, Y., & Meng, Y. (2025). Identification of the Chalcone Synthase Gene Family: Revealing the Molecular Basis for Floral Colour Variation in Wild Aquilegia oxysepala in Northeast China. Agronomy, 15(12), 2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122883