Rice Responds to Different Light Conditions by Adjusting Leaf Phenotypic and Panicle Traits to Optimize Shade Tolerance Stability and Yield

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

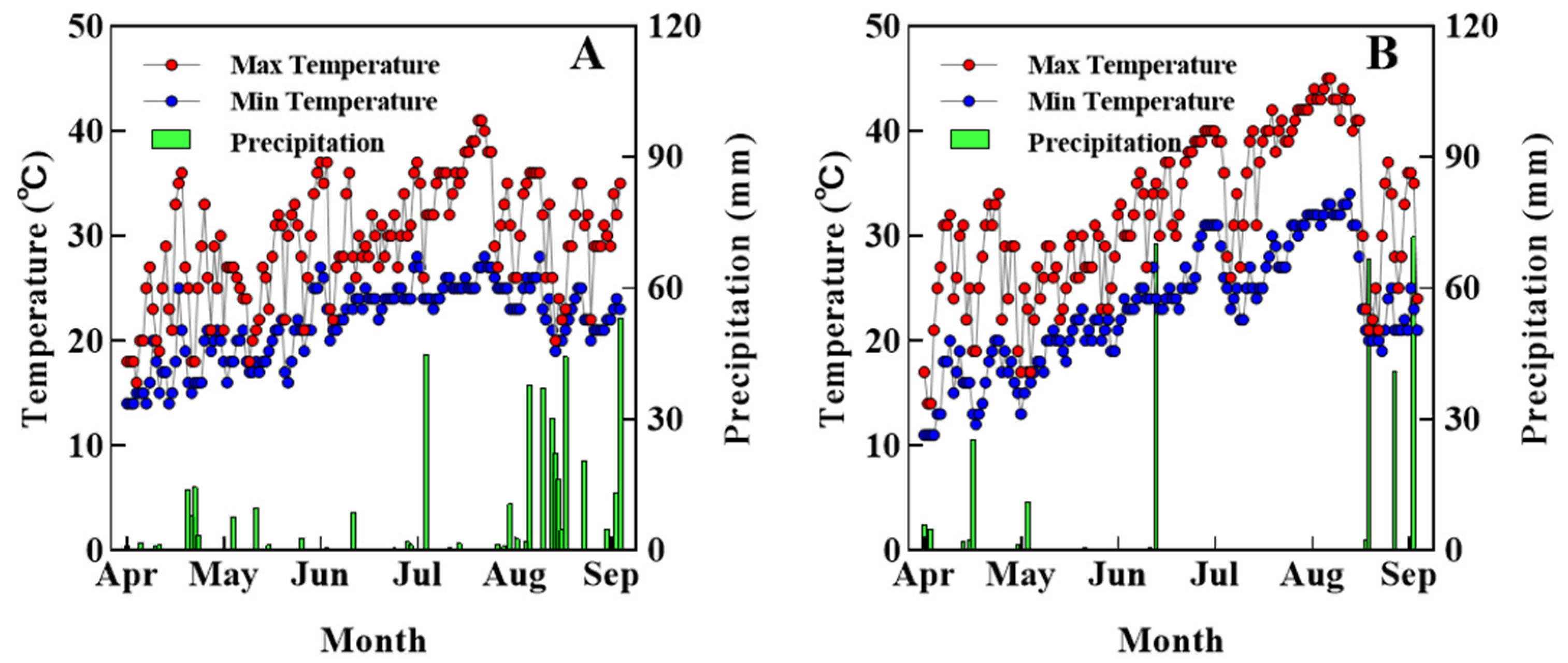

2.1. Experimental Design and Field Management

2.2. Morphological Characteristics and Physiological Measurements

2.3. Dry Mass Measurement

2.4. Yield Component Measurement

2.5. Shade Tolerance Coefficients

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

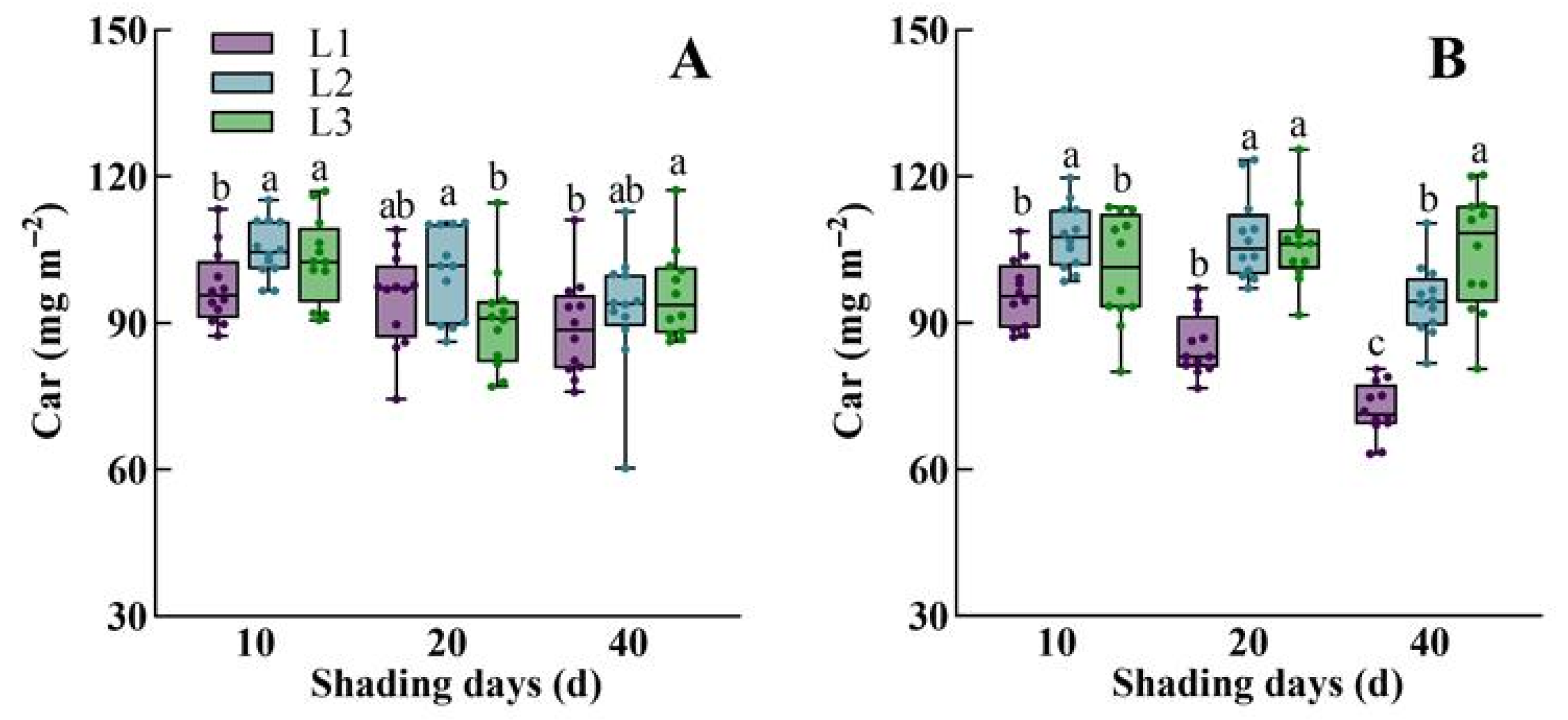

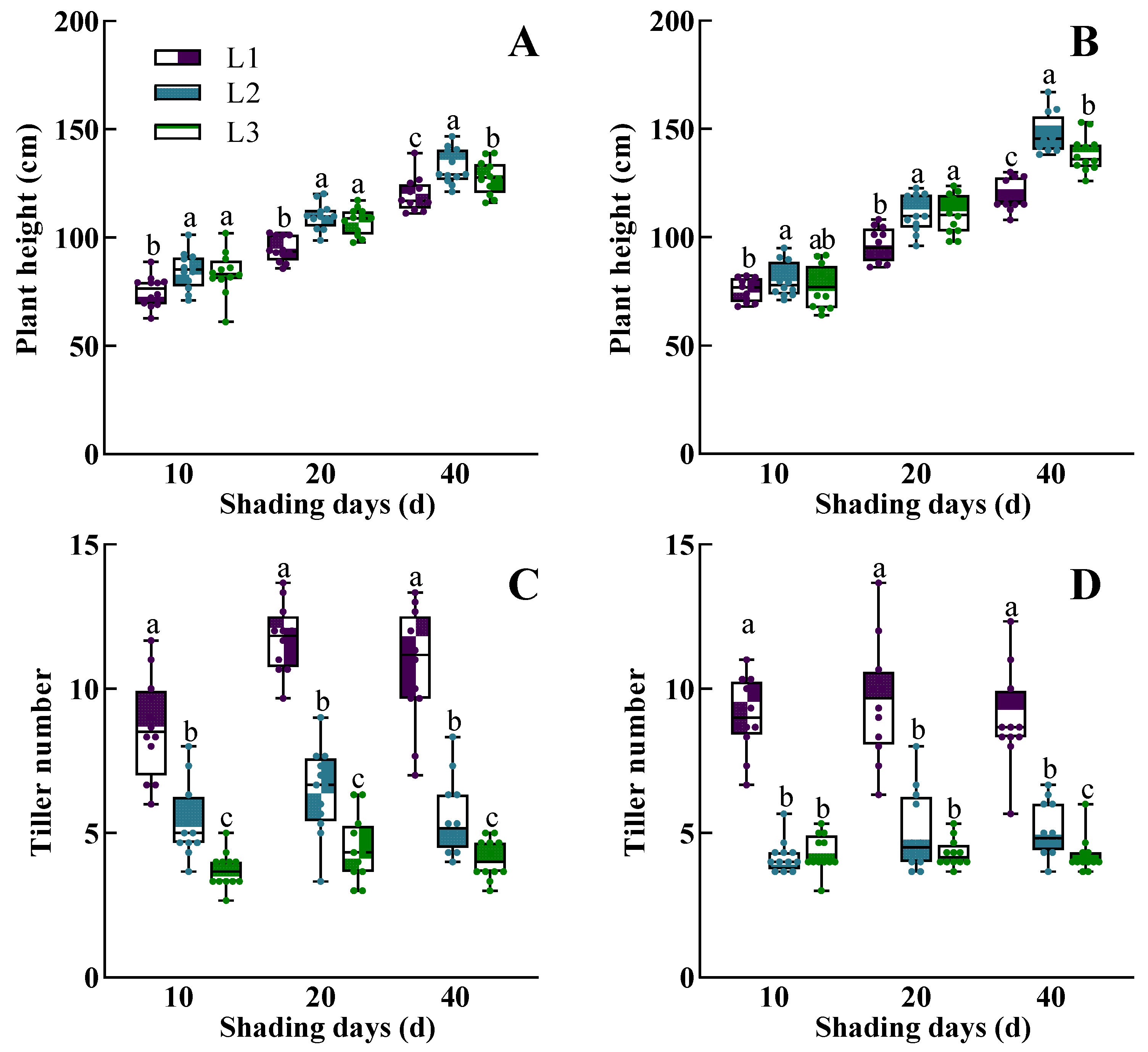

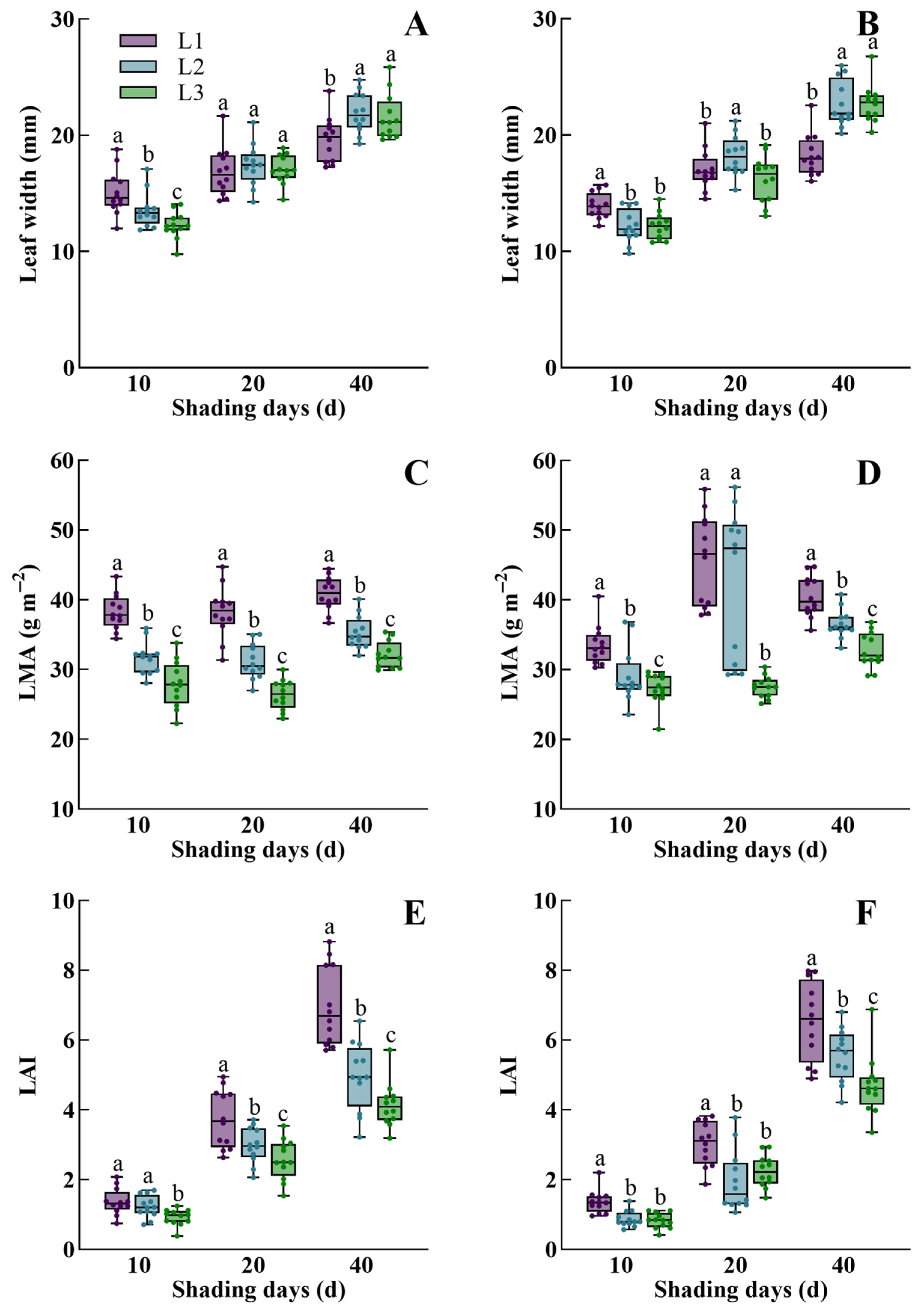

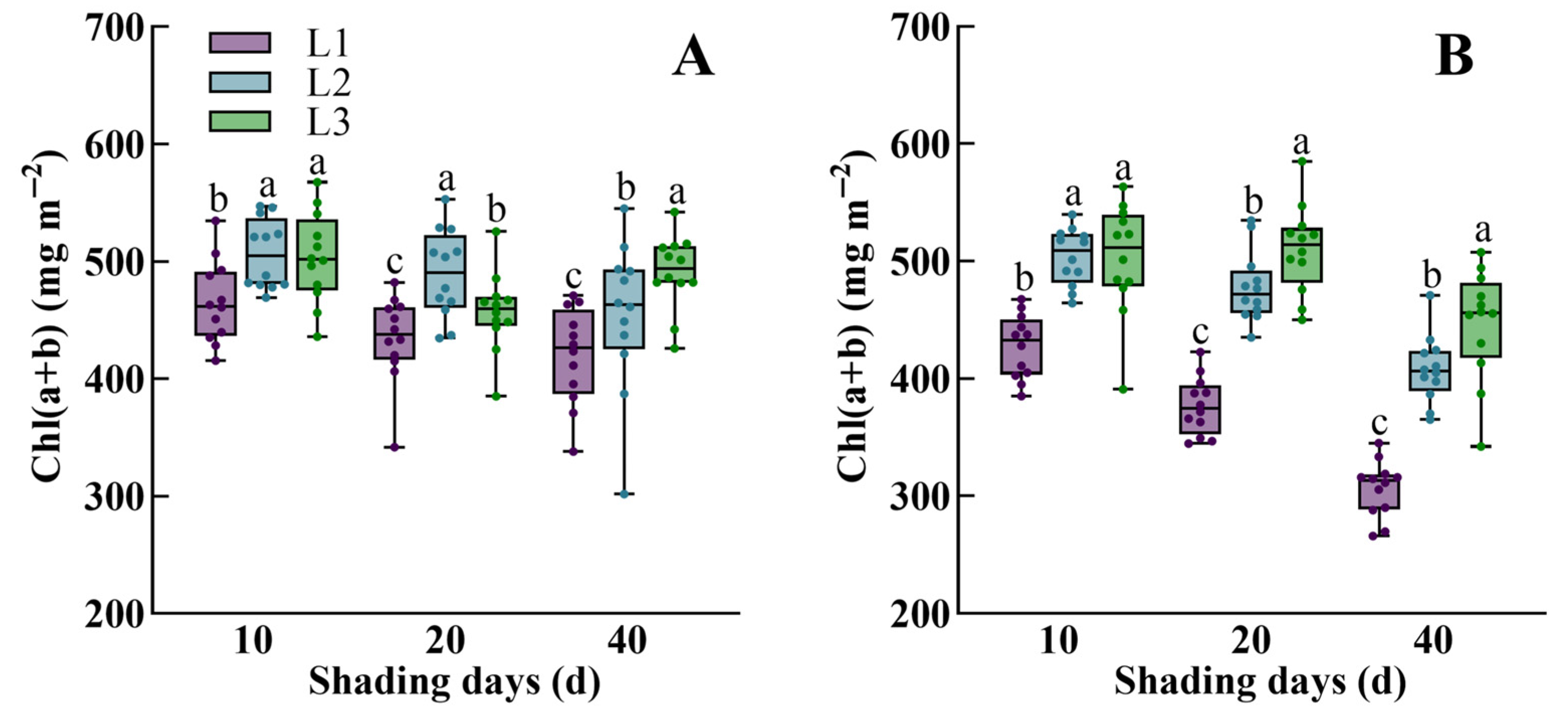

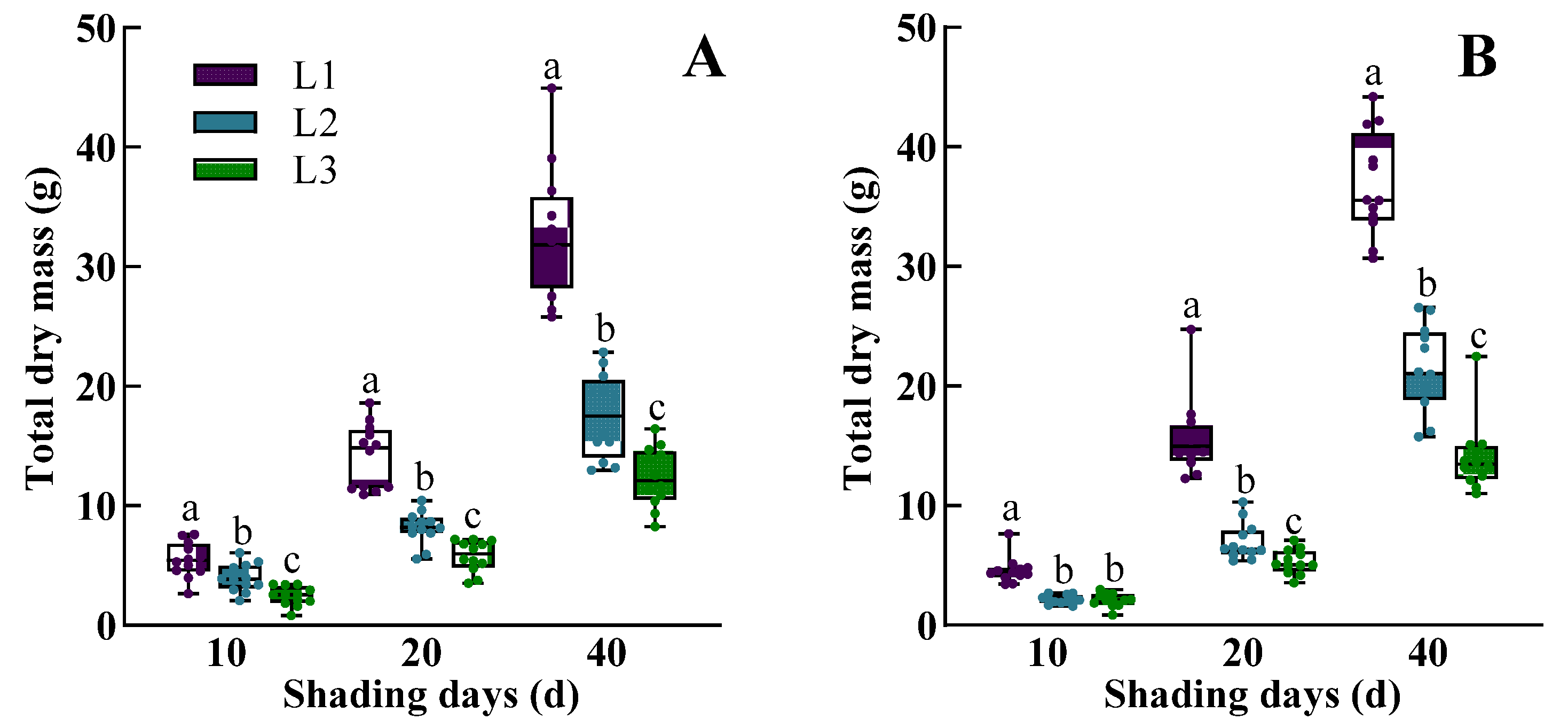

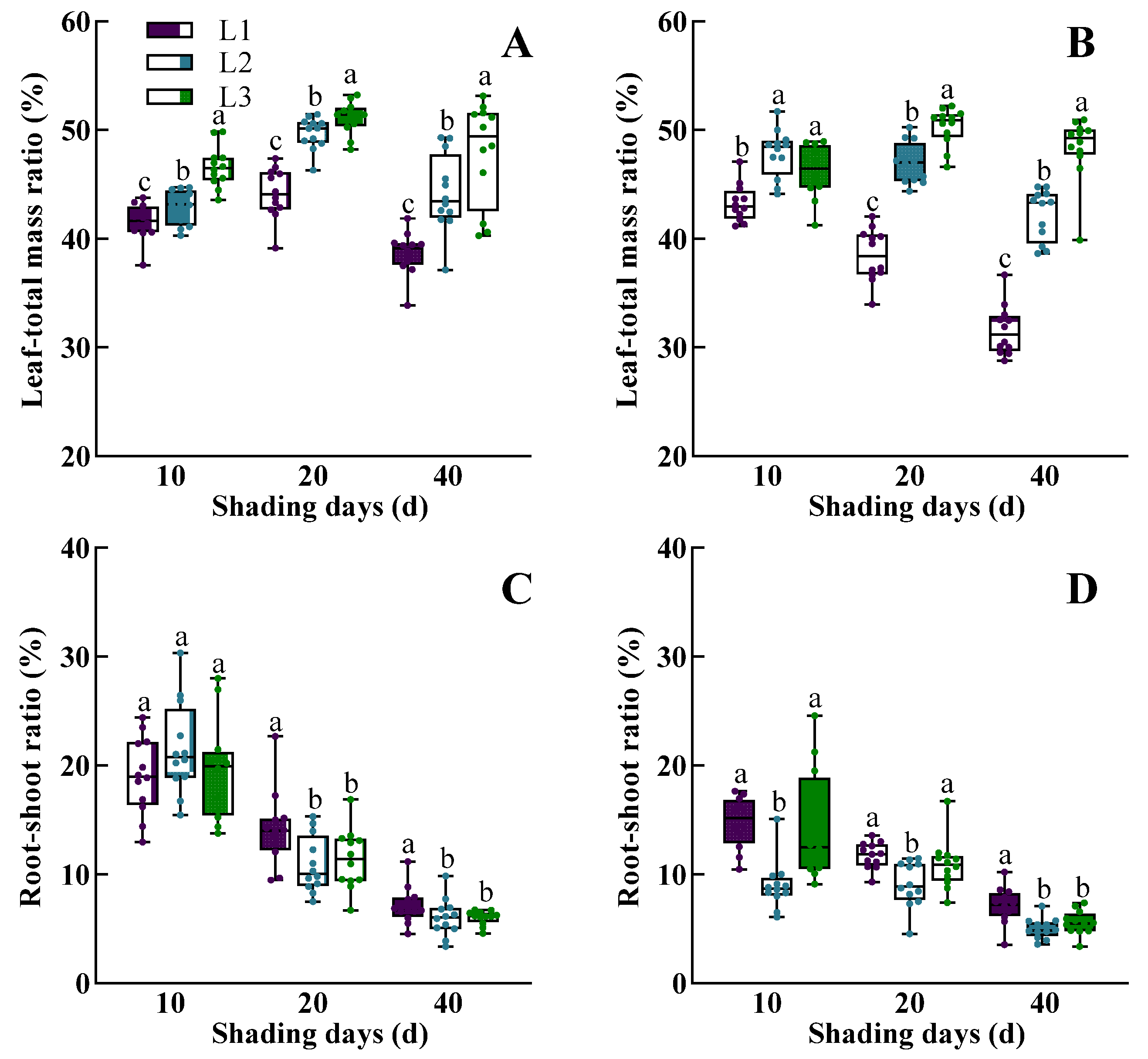

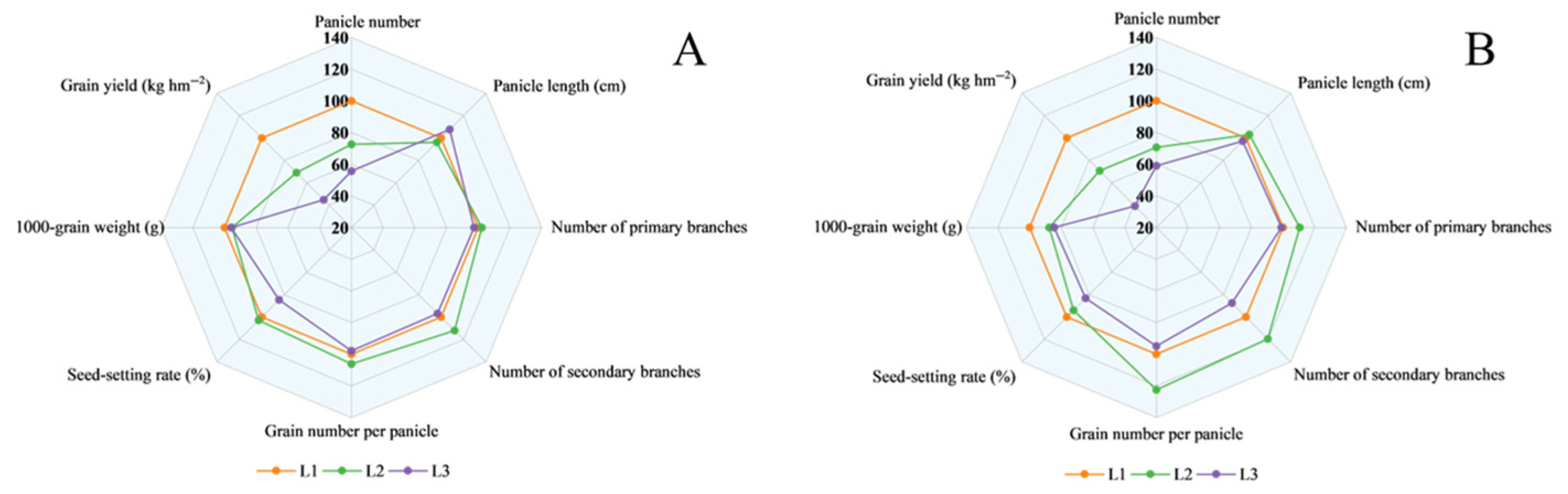

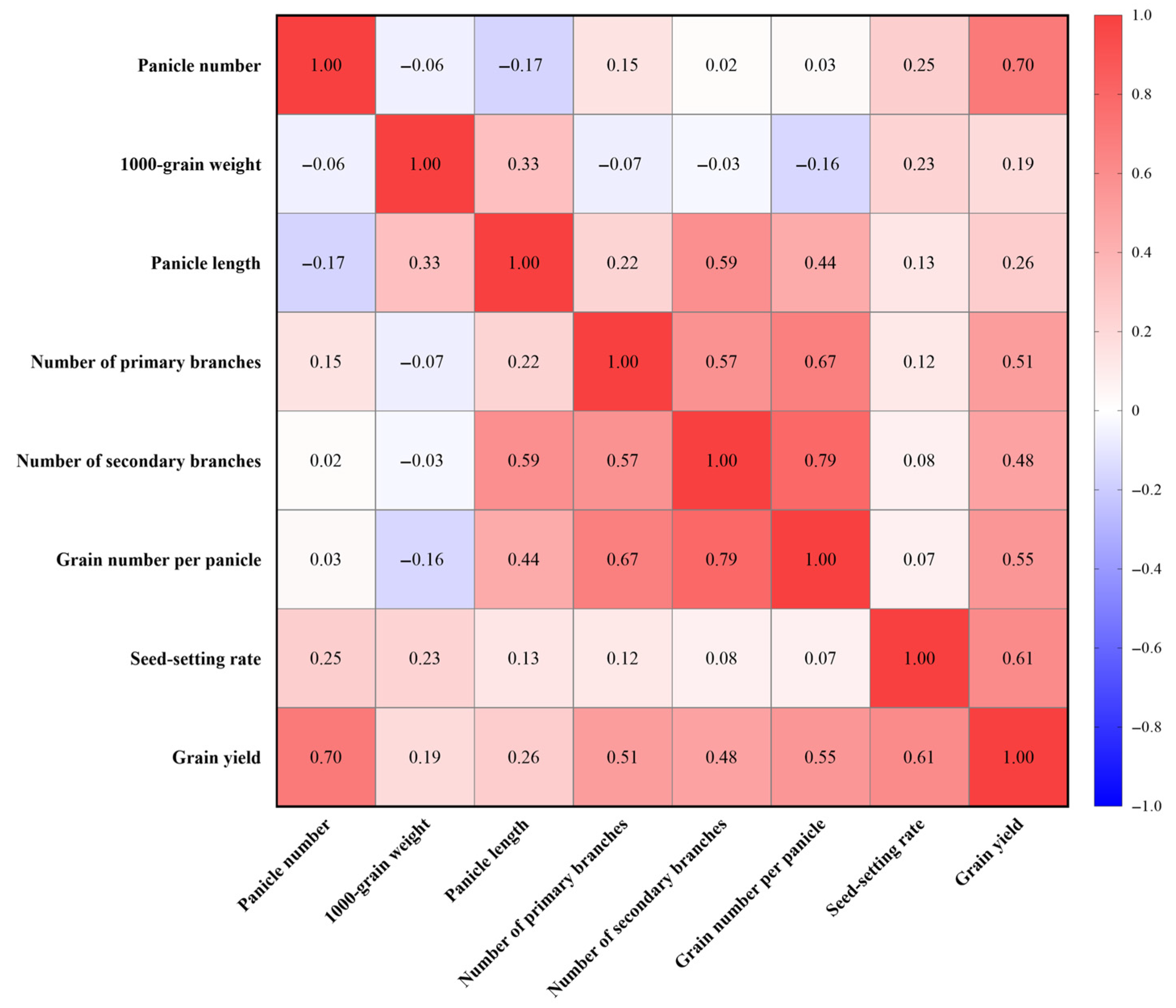

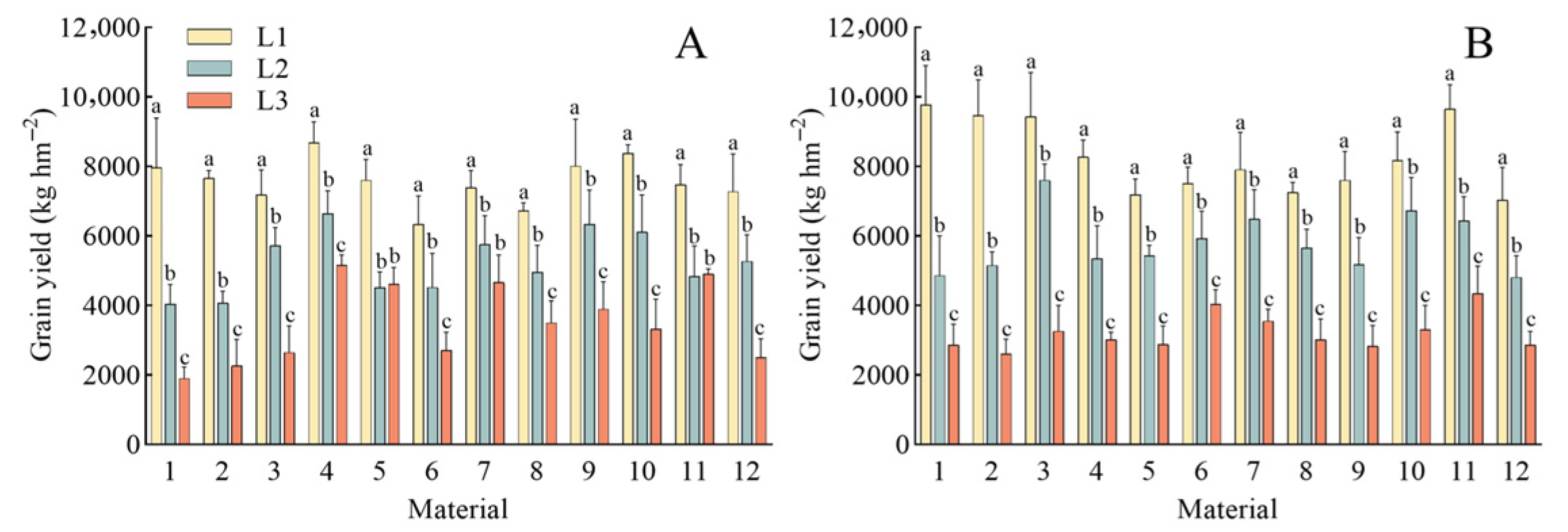

3.1. The Dynamic Response of Morphological Characteristics, Physiological Traits, Dry Mass Accumulation, and Yield of Rice to Low Light

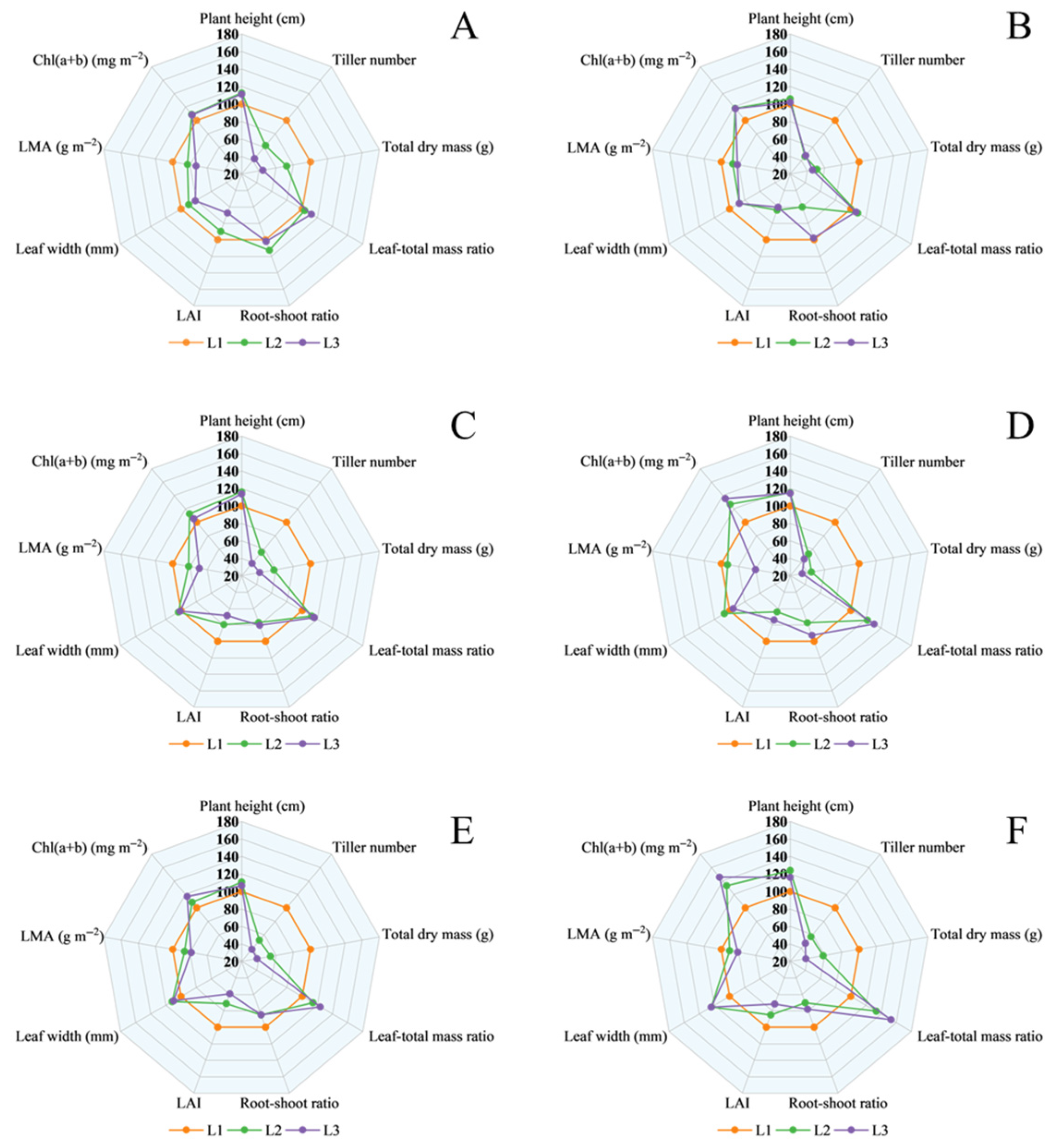

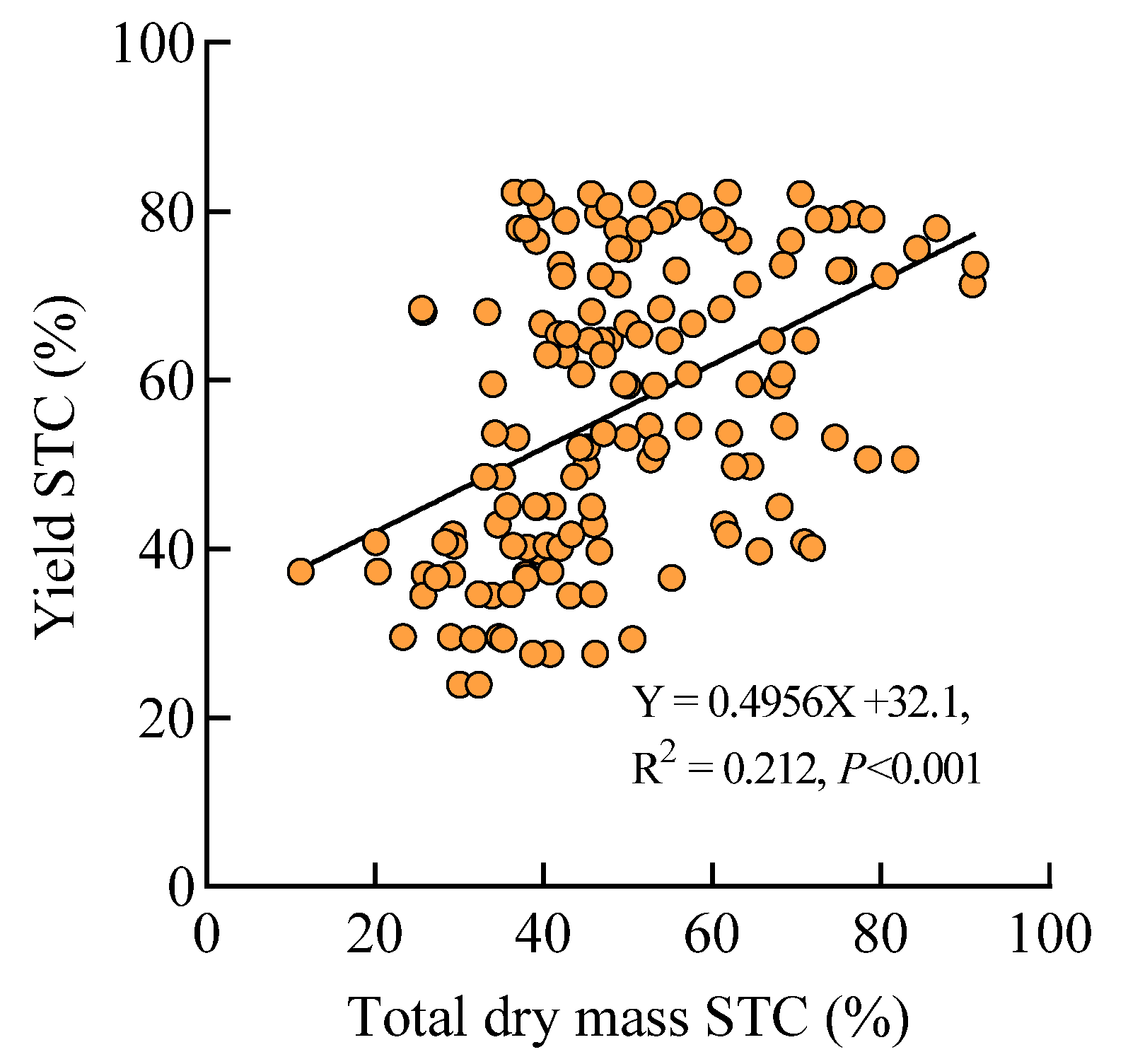

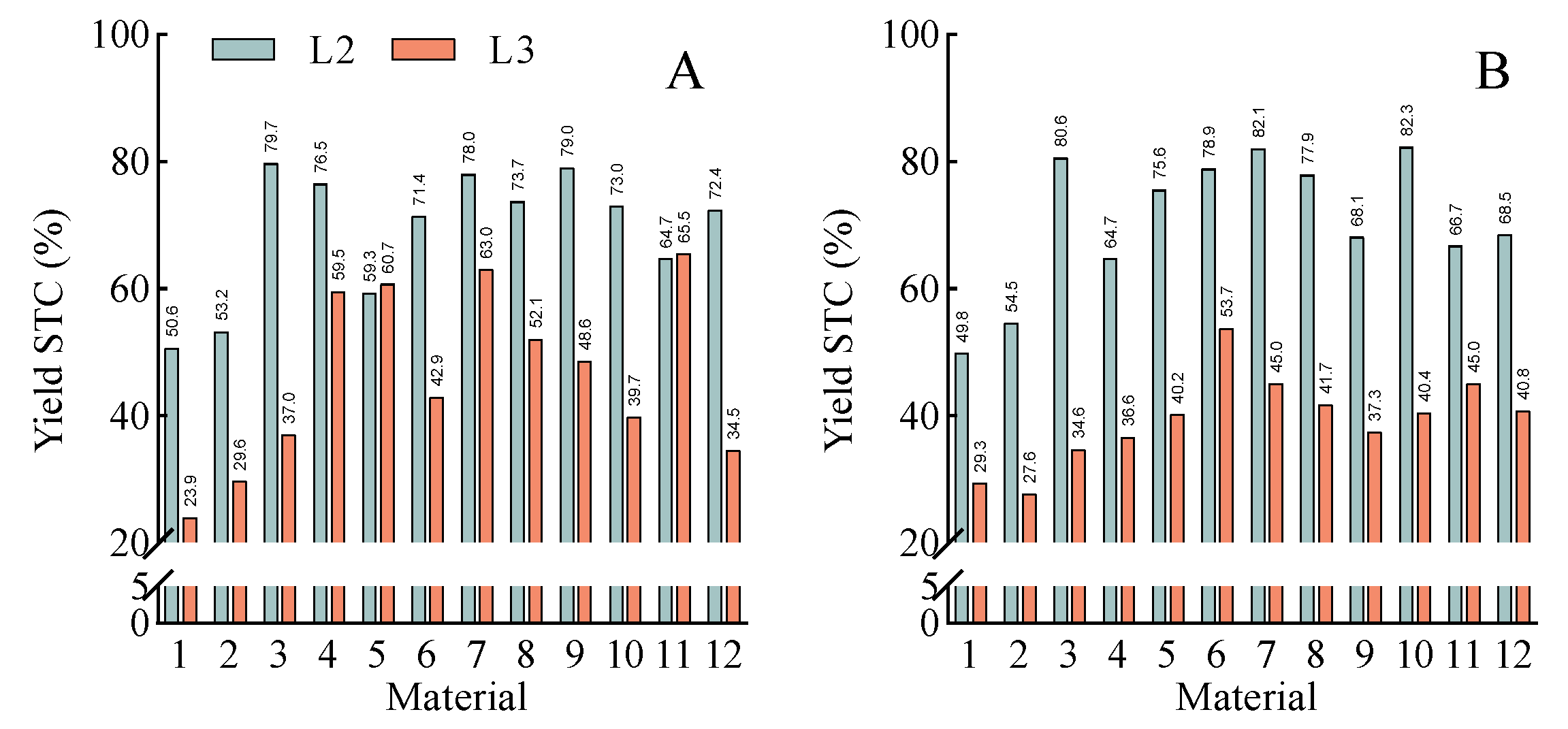

3.2. Analysis of Shade Tolerance Coefficients for Agronomic Traits

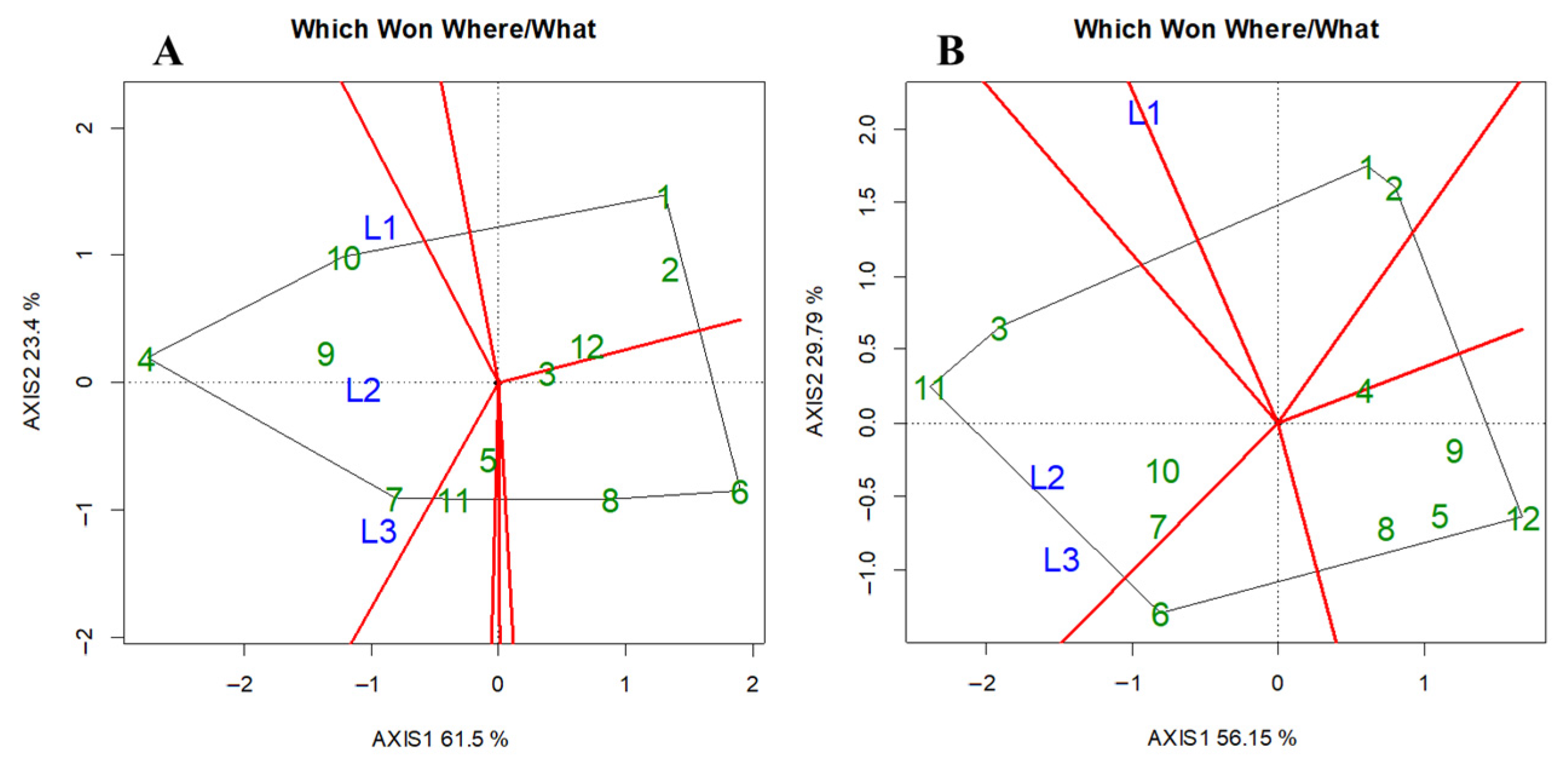

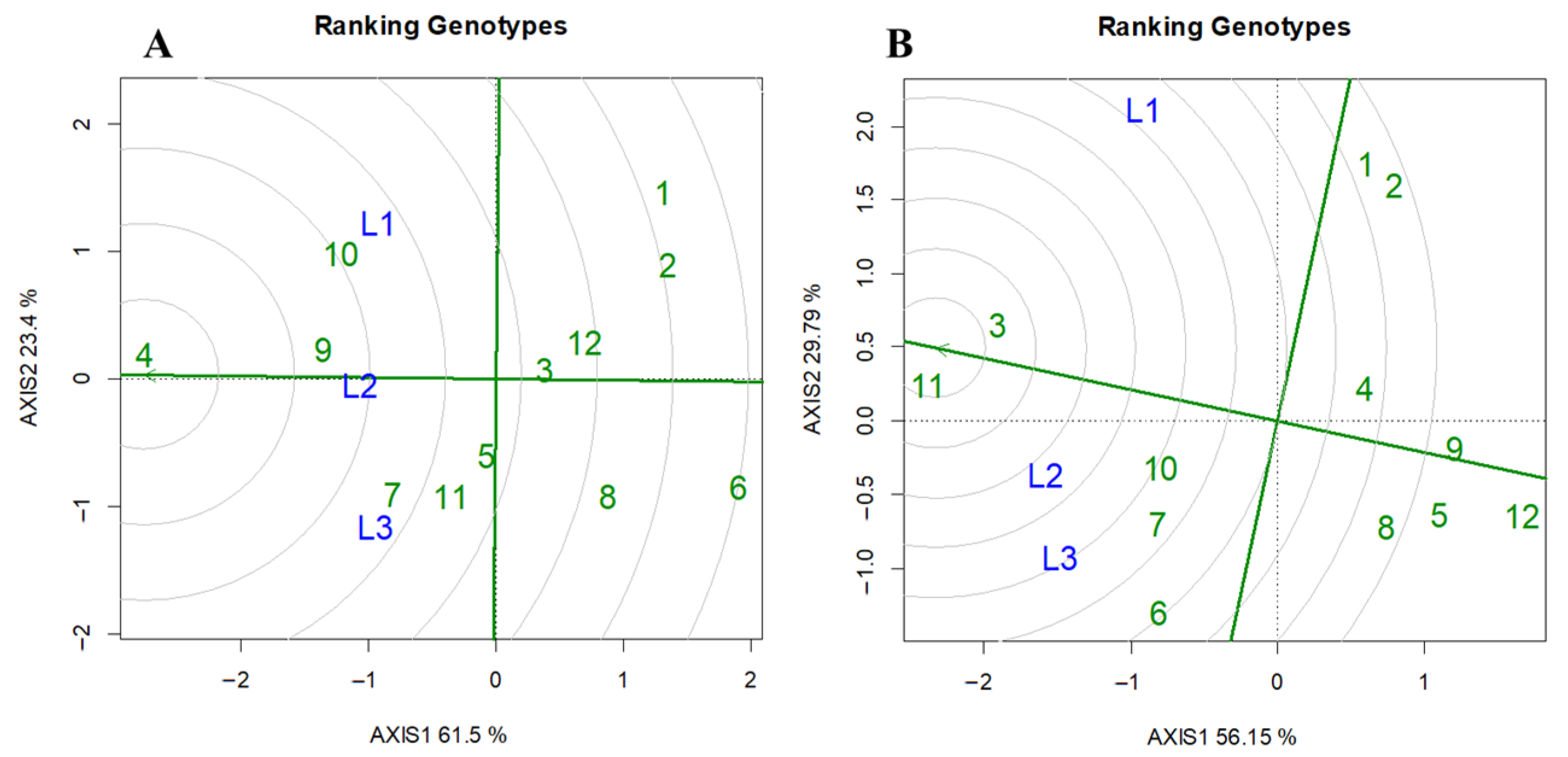

3.3. Differences in Shade Tolerance Among Rice Cultivars

4. Discussion

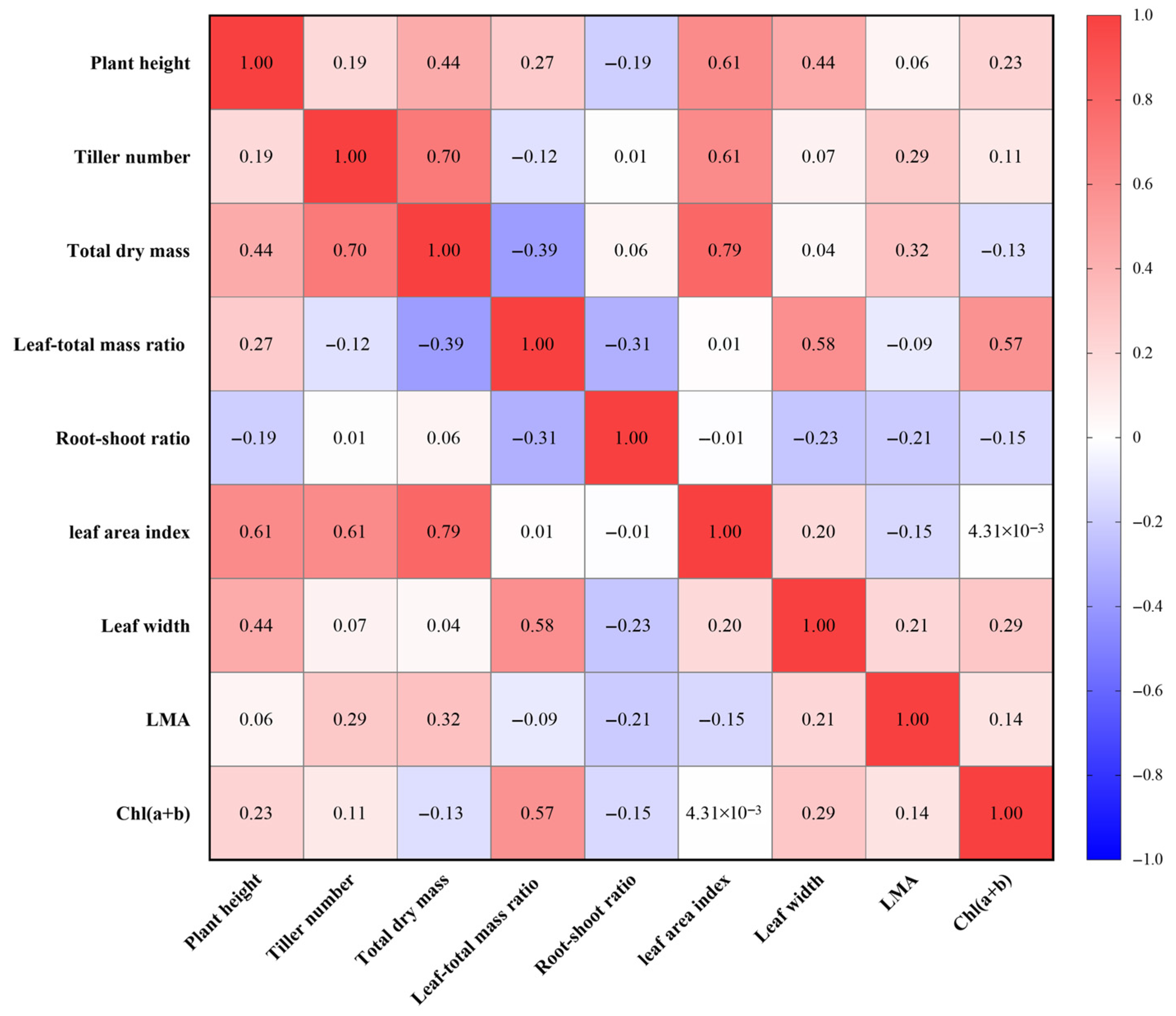

4.1. The Change in Leaf Width Is the Basic Feature of Rice Acclimatization to Low Light

4.2. Synergistic Interactions of Plant Phenotype Drives Low-Light Acclimatization in Rice

4.3. Panicle Number Is a Crucial Determinant of Rice Yield Under Low-Light Conditions

4.4. Comprehensive Evaluation of Rice Shade Tolerance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMA | Leaf mass per area |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| Chl | Chlorophyll |

| Car | Carotenoid |

| STC | Shade tolerance coefficient |

Appendix A

| Month | Sunshine Duration (h) | Total Solar Radiation (MJ m−2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Apr | 117.7 | 224.5 | 133.7 | 202.6 |

| May | 187.1 | 213.0 | 182.9 | 209.0 |

| Jun | 241.1 | 228.2 | 197.4 | 202.3 |

| Jul | 274.1 | 342.1 | 250.5 | 304.6 |

| Aug | 237.5 | 345.4 | 214.8 | 310.4 |

| Sep | 243.4 | 167.5 | 220.8 | 165.5 |

| Cultivar NO. | 2021 | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L1 | L2 | L3 | |

| 1 | 7973 ± 1422 a | 4037 ± 568 b | 1904 ± 332 c | 9776 ± 1125 a | 4868 ± 1139 b | 2863 ± 605 c |

| 2 | 7662 ± 221 a | 4077 ± 334 b | 2267 ± 757 c | 9462 ± 1033 a | 5157 ± 385 b | 2611 ± 427 c |

| 3 | 7184 ± 719 a | 5725 ± 516 b | 2656 ± 758 c | 9435 ± 1267 a | 7601 ± 473 b | 3268 ± 734 c |

| 4 | 8681 ± 608 a | 6642 ± 662 b | 5167 ± 291 c | 8271 ± 494 a | 5353 ± 945 b | 3023 ± 213 c |

| 5 | 7608 ± 601 a | 4515 ± 449 b | 4619 ± 475 b | 7192 ± 454 a | 5434 ± 297 b | 2888 ± 525 c |

| 6 | 6346 ± 806 a | 4528 ± 976 b | 2720 ± 517 c | 7518 ± 470 a | 5931 ± 788 b | 4040 ± 415 c |

| 7 | 7396 ± 490 a | 5770 ± 819 b | 4662 ± 792 b | 7914 ± 1069 a | 6494 ± 840 b | 3560 ± 331 c |

| 8 | 6736 ± 218 a | 4961 ± 776 b | 3507 ± 630 c | 7257 ± 292 a | 5652 ± 546 b | 3025 ± 590 c |

| 9 | 8016 ± 1347 a | 6336 ± 987 b | 3892 ± 795 c | 7605 ± 832 a | 5180 ± 776 b | 2839 ± 585 c |

| 10 | 8380 ± 246 a | 6118 ± 1063 b | 3329 ± 855 c | 8179 ± 811 a | 6727 ± 953 b | 3306 ± 700 c |

| 11 | 7489 ± 568 a | 4846 ± 871 b | 4903 ± 149 b | 9654 ± 701 a | 6438 ± 698 b | 4347 ± 785 c |

| 12 | 7285 ± 1080 a | 5272 ± 761 b | 2512 ± 537 c | 7034 ± 939 a | 4816 ± 615 b | 2869 ± 388 c |

| Factors | Panicle Number | Panicle Length (cm) | Number of Primary Branches | Number of Secondary Branches | Grain Number per Panicle | Seed-Setting Rate (%) | 1000-Grain Weight (g) | Grain Yield (kg hm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Cultivar | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Light × Cultivar | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Light × Year | ns | *** | ns | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** |

| Cultivar × Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Light × Cultivar × Year | *** | * | *** | * | *** | *** | *** | * |

| Factors | Plant Height (cm) | Tiller Number | Total Dry Mass (g) | Leaf-Total Mass Ratio | Root-Shoot Ratio | LAI | Leaf Width (mm) | Leaf Mass per Area (g m−2) | Chl(a + b) (mg m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Cultivar | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Year | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * |

| Light × Cultivar | *** | *** | *** | ns | ** | *** | ns | *** | * |

| Light × Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** |

| Cultivar × Year | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns |

| Light × Cultivar × Year | *** | *** | *** | * | ns | *** | ns | ** | ns |

| Factors | Plant Height (cm) | Tiller Number | Total Dry Mass (g) | Leaf-Total Mass Ratio | Root-Shoot Ratio | LAI | Leaf Width (mm) | Leaf Mass per Area (g m−2) | Chl(a + b) (mg m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Cultivar | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Year | ** | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** | ns |

| Light × Cultivar | ns | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** | ns | *** | ns |

| Light × Year | ns | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** | ** | *** | *** |

| Cultivar × Year | *** | * | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | ns |

| Light × Cultivar × Year | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | *** | * | *** | ns |

| Factors | Plant Height (cm) | Tiller Number | Total Dry Mass (g) | Leaf-Total Mass Ratio | Root-Shoot Ratio | LAI | Leaf Width (mm) | Leaf Mass per Area (g m−2) | Chl(a + b) (mg m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Cultivar | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | ns | ns | *** |

| Light × Cultivar | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Light × Year | *** | *** | * | *** | ns | *** | *** | ns | *** |

| Cultivar × Year | ns | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** | * | ns | ** |

| Light × Cultivar × Year | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | ** | ns | *** |

References

- Hatzianastassiou, N.; Papadimas, C.D.; Matsoukas, C.; Pavlakis, K.; Fotiadi, A.; Wild, M.; Vardavas, I. Recent regional surface solar radiation dimming and brightening patterns: Inter-hemispherical asymmetry and a dimming in the Southern Hemisphere. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2012, 13, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatis, M.; Hatzianastassiou, N.; Korras-Carraca, M.; Matsoukas, C.; Wild, M.; Vardavas, I. Which are the main drivers of global dimming and brightening? Atmos. Res. 2025, 322, 108140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Han, Y.; Jiang, W.H. Distribution Characters of Fog in Chongqing and Causes of Fog in November 7, 2006. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 726–731, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Zhou, L.; Liao, X.; Zhang, K.; Aer, L.; Yang, E.; Deng, J.; Zhang, R. Effects of low light after heading on the yield of direct seeding rice and its physiological response mechanism. Plants 2023, 12, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Deng, F.; Ren, W. Effect of different shading materials on grain yield and quality of rice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, I.; Hussain, S.; Raza, M.; Iqbal, N.; Ahsan Asghar, M.; Raza, A.; Fan, Y.; Mumtaz, M.; Shoaib, M.; Ansar, M.; et al. Crop photosynthetic response to light quality and light intensity. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resurreccion, A.; Makino, A.; Bennett, J.; Mae, T. Effect of light intensity on the growth and photosynthesis of rice under different sulfur concentrations. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2002, 48, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, F.; Yu, E.; Sun, L.; Guo, J.; Xing, Z.; Guo, B.; Wei, H.; Huo, Z.; Xu, K.; et al. Effect of low temperature and weak light combined stress during panicle differentiation on grain yield and physiological property in rice. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Shi, C.; Jiang, M. Simulation model for assessing high-temperature stress on rice. Agronomy 2024, 14, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Deng, F.; Zeng, Y.; Li, B.; He, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Tao, Y.; et al. Low light stress increases chalkiness by disturbing starch synthesis and grain filling of rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Q. Research progress on the impacts of low light intensity on rice growth and development. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2013, 21, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Nimitha, K.; Saha, S.; Mahapatra, N.; Bhattacharya, K.; Kundu, R.; Ganguly, S.; Sen, P.; Saha, A.; Purkayastha, S.; et al. Identification and analysis of low light responsive yield enhancing QTLs in rice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarge, T.; Seassau, C.; Martin, M.; Bueno, C.; Clément-Vidal, A.; Schreck, E.; Luquet, D. Regulation and recovery of sink strength in rice plants grown under changes in light intensity. Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U.; Laza, M.; Soulié, J.; Pasco, R.; Mendez, K.; Dingkuhn, M. Compensatory phenotypic plasticity in irrigated rice: Sequential formation of yield components and simulation with SAMARA model. Field Crops Res. 2016, 193, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Purkayastha, S.; Nimitha, K.; Ganguly, S.; Das, S.; Ganguly, S.; Mahapatra, N.; Bhattacharya, K.; Das, D.; Saha, A.; et al. Rice (Oryza sativa) alleviates photosynthesis and yield loss by limiting specific leaf weight under low light intensity. Funct. Plant Biol. 2023, 50, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Deng, F.; Ren, W. Shading tolerance in rice is related to better light harvesting and use efficiency and grain filling rate during grain filling period. Field Crops Res. 2015, 180, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xiao, F.; Huang, D.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Jin, S.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Paul, M.; Liu, Z. High canopy photosynthesis before anthesis explains the outstanding yield performance of rice cultivars with ideal plant architecture. Field Crops Res. 2024, 306, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Analysis 1983, 11, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zou, D.; Li, C.; Zhou, W.; Li, K.; Tang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Li, X.; Cao, L. Analysis of characteristics of rice tillering dynamics influenced by sowing dates based on DTM. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Sheng, T.; Zhong, X.; Ye, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, L.; Tian, X.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y. Delayed leaf senescence improves radiation use efficiency and explains yield advantage of large panicle-type hybrid rice. Plants 2023, 12, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, S.; Ohkubo, S.; San, N.; Nakkasame, A.; Tomisawa, K.; Katsura, K.; Ookawa, T.; Nagano, A.; Adachi, S. Maintaining higher leaf photosynthesis after heading stage could promote biomass accumulation in rice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Lü, Y.; Yin, C.; Li, C. Morphological and physiological plasticity of woody plant in response to high light and low light. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2005, 11, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loretta, G. Plant Phenotypic Plasticity in Response to Environmental Factors. Adv. Bot. 2014, 2014, 208747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, M.; Brini, F.; Brestic, M.; Landi, M. Interplay between low light and hormone-mediated signaling pathways in shade avoidance regulation in plants. Plant Stress 2023, 9, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Knapik, D.; Escudero, A.; Mediavilla, S.; Scoffoni, C.; Zailaa, J.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Alvarez-Arenas, T.; Molins, A.; Alonso-Forn, D.; Ferrio, J.; et al. Deciduous and evergreen oaks show contrasting adaptive responses in leaf mass per area across environments. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, N. Chlorophyll fluorescence: A probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Jiang, D.; Wollenweber, B.; Dai, T.; Cao, W. Effects of shading on morphology, physiology and grain yield of winter wheat. Eur. J. Agron. 2010, 33, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierik, R.; Ballaré, C. Control of plant growth and defense by photoreceptors: From mechanisms to opportunities in agriculture. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gommers, C.M.M.; Visser, E.J.W.; Onge, K.R.S.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Pierik, R. Shade tolerance: When growing tall is not an option. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidnia, F.; Taherian, M.; Nazeri, S. Graphical analysis of multi-environmental trials for wheat grain yield based on GGE-biplot analysis under diverse sowing dates. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NO. | Cultivar | Type | NO. | Cultivar | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zhong 9 You 804 | indica | 7 | Le You 918 | indica |

| 2 | Xida 8 You 727 | indica | 8 | Q You 12 | indica |

| 3 | Gang You 952 | indica | 9 | Yuxiang 203 | indica |

| 4 | Rong You 184 | indica | 10 | Chuankang You 65 | indica |

| 5 | Jia You 968 | indica | 11 | Shen 9 You 28 | indica |

| 6 | Zhong You 596 | indica | 12 | II You 602 | indica |

| Year | Parameter | L1 | L2 | L3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Panicle number | 6.38 ± 1.23 a | 4.63 ± 0.95 b | 3.55 ± 0.97 c |

| Panicle length (cm) | 26.48 ± 1.91 b | 27.07 ± 2.98 b | 28.50 ± 2.81 a | |

| Number of primary branches | 12.94 ± 1.85 b | 14.49 ± 2.41 a | 12.59 ± 1.63 b | |

| Number of secondary branches | 38.49 ± 7.23 a | 40.85 ± 11.16 a | 37.23 ± 12.91 a | |

| Grain number per panicle | 225.29 ± 38.86 a | 231.63 ± 46.72 a | 220.44 ± 52.38 a | |

| Seed-setting rate (%) | 89.67 ± 5.31 a | 85.49 ± 8.40 b | 75.82 ± 12.66 c | |

| 1000-grain weight (g) | 27.32 ± 4.01 a | 26.28 ± 2.58 a | 26.19 ± 2.79 a | |

| Grain yield (kg hm−2) | 7631.84 ± 985.71 a | 5268.16 ± 1103.77 b | 3414.09 ± 1198.35 c | |

| 2022 | Panicle number | 6.96 ± 1.27 a | 4.91 ± 0.96 b | 4.10 ± 0.64 c |

| Panicle length (cm) | 29.15 ± 1.95 ab | 30.03 ± 2.71 a | 28.29 ± 3.32 b | |

| Number of primary branches | 14.00 ± 1.14 b | 15.48 ± 1.42 a | 13.86 ± 1.38 b | |

| Number of secondary branches | 48.73 ± 8.62 b | 58.25 ± 12.17 a | 42.65 ± 11.82 c | |

| Grain number per panicle | 255.19 ± 42.63 b | 312.77 ± 62.90 a | 242.38 ± 52.74 b | |

| Seed-setting rate (%) | 82.41 ± 6.26 a | 77.43 ± 8.49 b | 68.55 ± 11.50 c | |

| 1000-grain weight (g) | 25.68 ± 2.24 a | 22.51 ± 2.27 b | 21.71 ± 1.96 c | |

| Grain yield (kg hm−2) | 8252.50 ± 1242.88 a | 5827.01 ± 1080.51 b | 3229.00 ± 709.41 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Li, L.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Kong, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Lei, Z.; Gul, S.; He, G.; et al. Rice Responds to Different Light Conditions by Adjusting Leaf Phenotypic and Panicle Traits to Optimize Shade Tolerance Stability and Yield. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122855

Yang S, Li L, Wang G, Liu Y, Kong Y, Li X, Liu Y, Lei Z, Gul S, He G, et al. Rice Responds to Different Light Conditions by Adjusting Leaf Phenotypic and Panicle Traits to Optimize Shade Tolerance Stability and Yield. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122855

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shihui, Lingyi Li, Guangyuan Wang, Yan Liu, Ying Kong, Xianghui Li, Yufei Liu, Zhensheng Lei, Shareef Gul, Guanghua He, and et al. 2025. "Rice Responds to Different Light Conditions by Adjusting Leaf Phenotypic and Panicle Traits to Optimize Shade Tolerance Stability and Yield" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122855

APA StyleYang, S., Li, L., Wang, G., Liu, Y., Kong, Y., Li, X., Liu, Y., Lei, Z., Gul, S., He, G., & Yao, H. (2025). Rice Responds to Different Light Conditions by Adjusting Leaf Phenotypic and Panicle Traits to Optimize Shade Tolerance Stability and Yield. Agronomy, 15(12), 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122855