Mapping Yield and Fusarium Wilt on Green Bean Combining Vegetation Indices in Different Management Zones

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Field Management

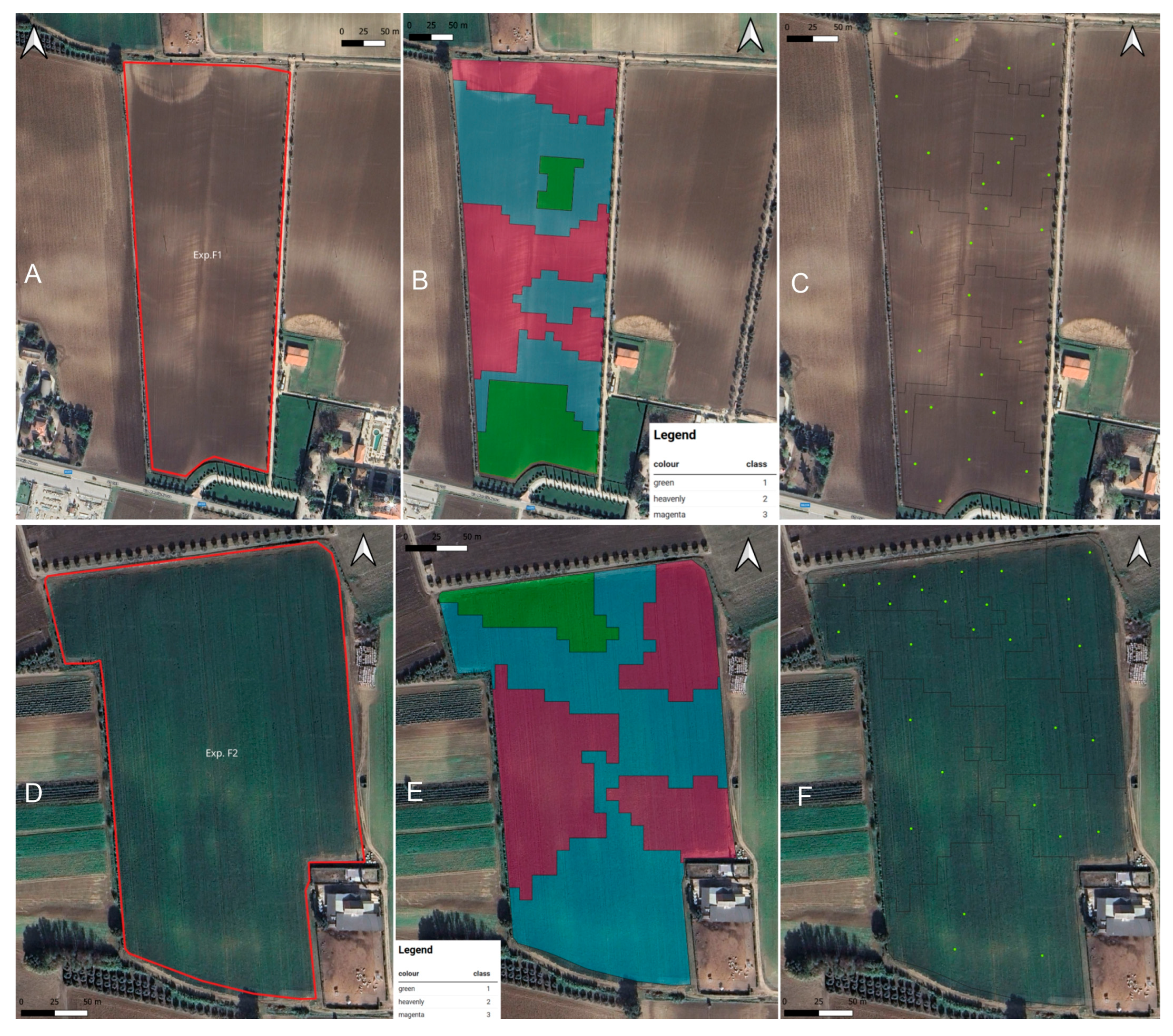

2.2. Definition of Management Unit Zones and Soil Analysis

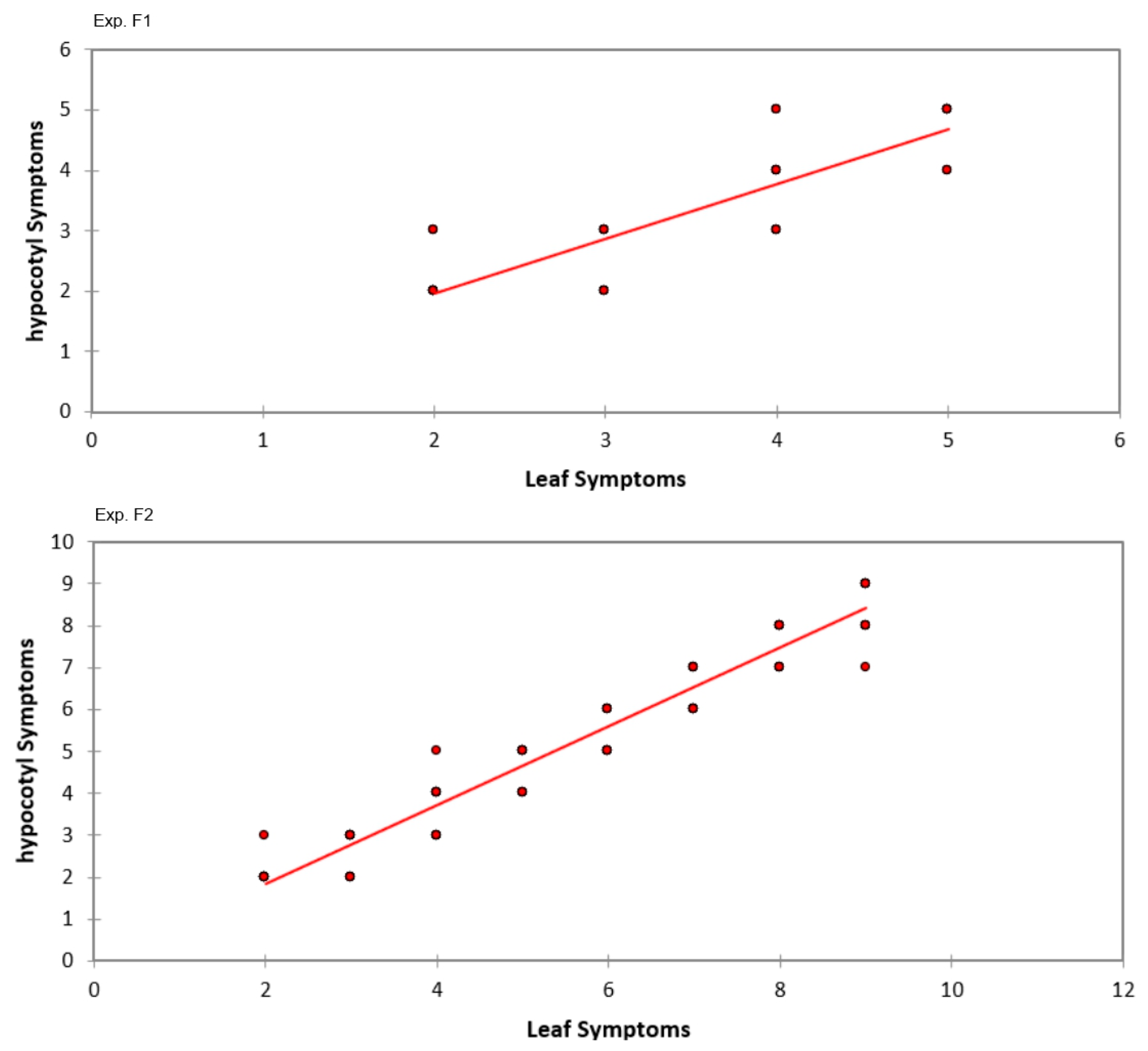

2.3. Incidence and Severity of Fusarium Wilt Leaf Symptoms, Evaluation of Yield Losses, and Correlation Between Root and Leaf Symptoms

2.4. Isolation of Pathogens from Symptomatic Plants

2.5. Disease Mapping

2.6. Yield Mapping

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

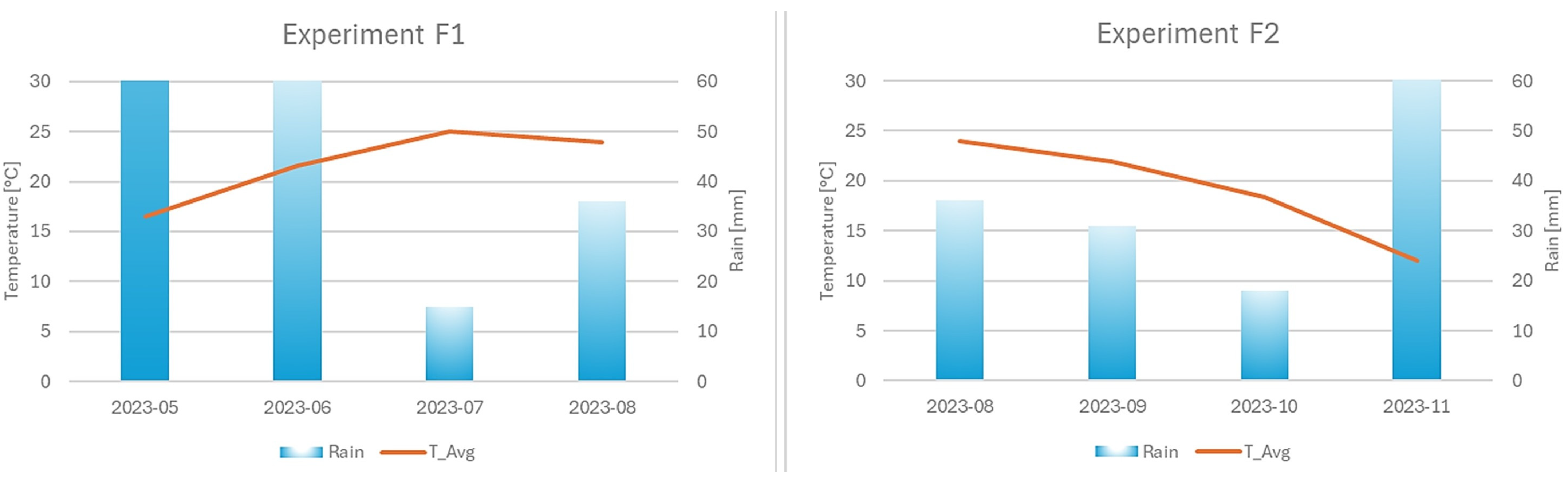

3.1. Meteorological Data

3.2. Soil Characteristics

3.3. Survey of Symptoms of Fungal Diseases

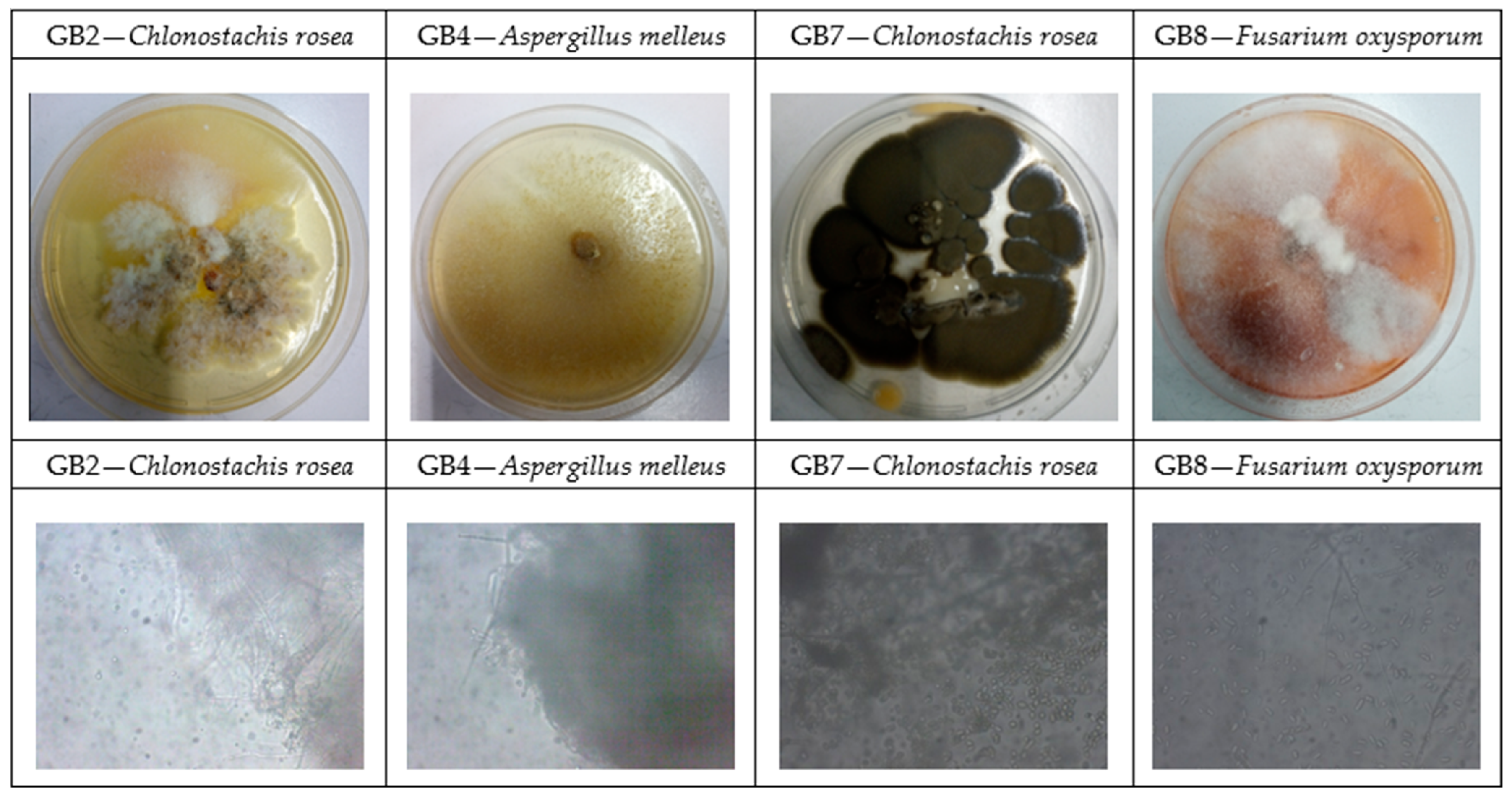

3.4. Isolation and Identification of Fungal Species

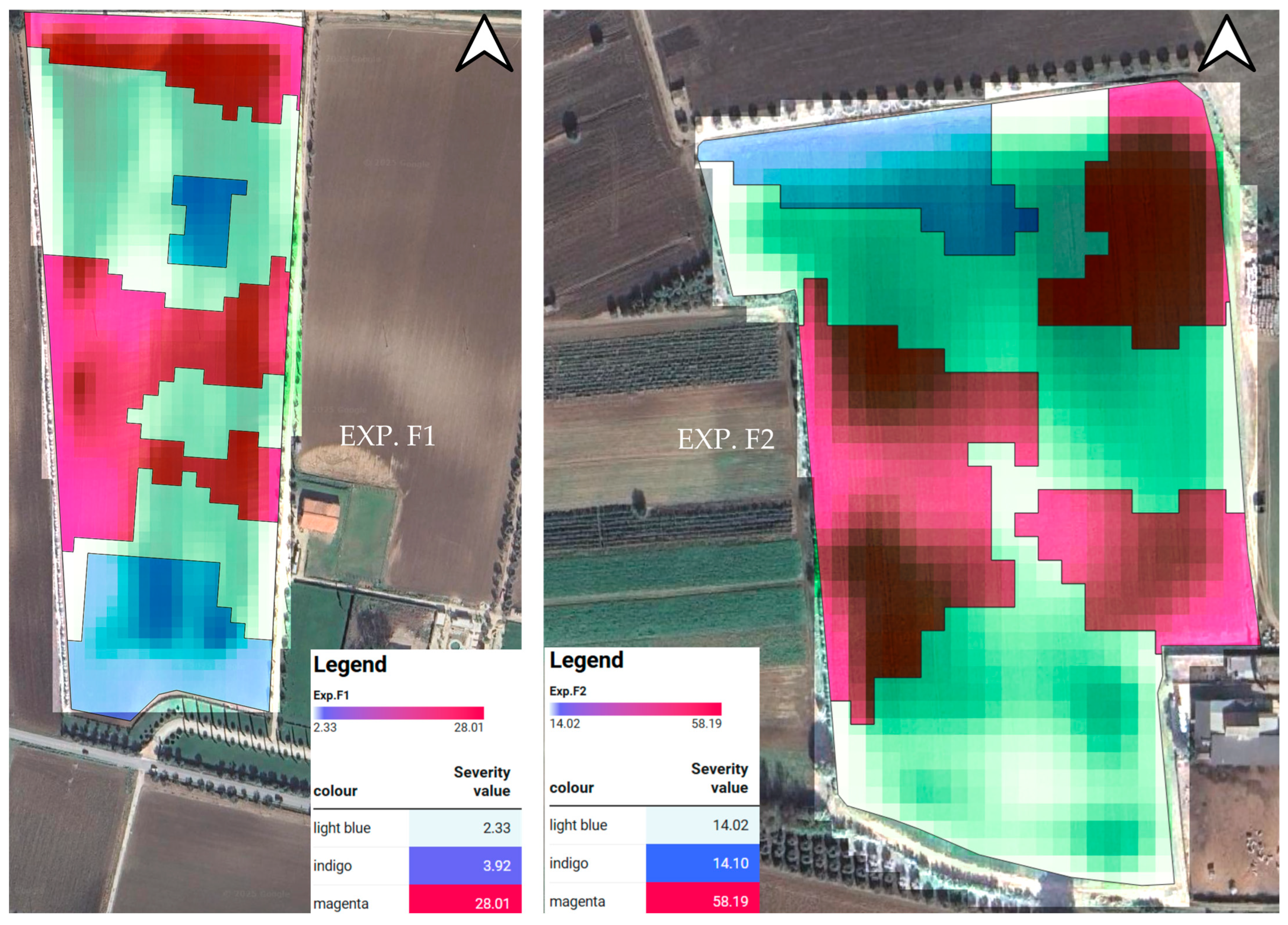

3.5. Disease Mapping

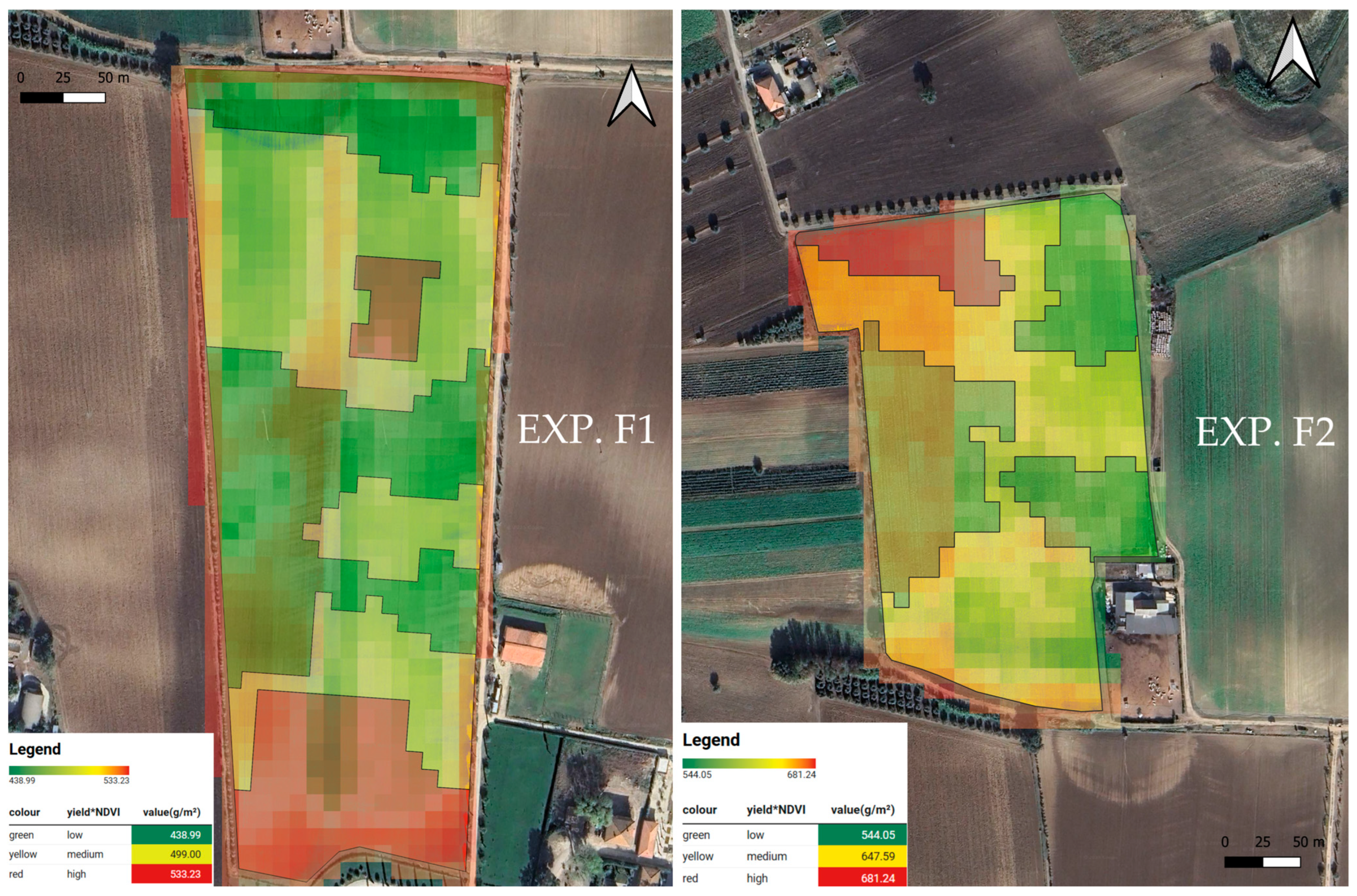

3.6. Yield Mapping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katalin, T.G.; Rahoveanu, T.; Magdalena, M.; István, T. Sustainable new agricultural technology—Economic aspects of precision crop protection. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 8, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, D.J. Twenty five years of remote sensing in precision agriculture: Key advances and remaining knowledge gaps. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 114, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelpfennig, D. Crop production costs, profits, and ecosystem stewardship with precision agriculture. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groß, J.; Gentsch, N.; Boy, J.; Heuermann, D.; Schweneker, D.; Feuerstein, U.; Brunner, J.; von Wirén, N.; Guggenberger, G.; Bauer, B. Influence of small-scale spatial variability of soil properties on yield formation of winter wheat. Plant Soil 2023, 493, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Chhogyel, N.; Gopalakrishnan, T.; Hasan, M.K.; Jayasinghe, S.L.; Kariyawasam, C.S.; Kogo, B.K.; Ratnayake, S. Climate Change and Future of Agri-Food Production. In Future Foods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Miao, Y.; Wang, H.; Su, M.; Fan, M.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, P.; et al. A preliminary precision rice management system for increasing both grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency. Field Crops Res. 2013, 154, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaço, A.F.; Bramley, R.G.V. Do crop sensors promote improved nitrogen management in grain crops? Field Crops Res. 2018, 218, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán-Montes, B.; Serra, P.; Zabala, A.; Masó, J.; Pons, X. A near real-time spatial decision support system for improving sugarcane monitoring through a satellite mapping web browser. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPAG Precision Ag Definition. Available online: https://www.ispag.org (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Castrignanò, A.; Buttafuoco, G.; Quarto, R.; Parisi, D.; Rossel, R.A.V.; Terribile, F.; Langella, G.; Venezia, A. A geostatistical sensor data fusion approach for delineating homogeneous management zones in precision agriculture. Catena 2018, 167, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, N.R.; Costa, J.L. Delineation of management zones with soil apparent electrical conductivity to improve nutrient management. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 99, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabro, J.D.; Stevens, W.B.; Evans, R.G.; Iversen, W.M. Spatial variability and correlation of selected soil properties in the ap horizon of a crp grassland. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2010, 26, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Gonzalez, D.A.; Chokmani, K.; Cambouris, A.N.; D’Souza, M.L. Delineation of management zones based on the agricultural potential concept for potato production using optical satellite images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Ferreira Silva, C.; Manzione, R.L.; de Medeiros Oliveira, S.R. Exploring 20-year applications of geostatistics in precision agriculture in Brazil: What’s next? Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 2293–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Ferreira Silva, C.; Grego, C.R.; Manzione, R.L.; Oliveira, S.R.D.M.; Rodrigues, G.C.; Rodrigues, C.A.G.; Speranza, E.A.; Luchiari, A.; Koenigkan, L.V. Summarizing soil chemical variables into homogeneous management zones—Case study in a specialty coffee crop. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanucara, S.; Praticò, S.; Pioggia, G.; Di Fazio, S.; Modica, G. Web-based spatial decision support system for precision agriculture: A tool for delineating dynamic management unit zones (MUZs). Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.J.; Yang, J.S.; Zhang, T.J.; Gao, P.; Wang, X.P.; Hong, L.Z.; Wang, M.W. Determination of site-specific management zones using soil physico-chemical properties and crop yields in coastal reclaimed farmland. Geoderma 2014, 232–234, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasaponara, R.; Abate, N.; Masini, N. Early Identification of Vegetation Pest Diseases Using Sentinel 2 NDVI Time Series 2016–2023: The Case of Toumeyella Parvicorvis at Castel Porziano (Italy). IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleta, R.J.; Roro, A.G.; Terfa, M.T. Phenotypic and yield responses of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties to different soil moisture levels. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shohag, M.J.I.; Salgado, E.M.; Gluck, M.C.; Liu, G. Evaluating the impact of phosphorus and solid oxygen fertilization on snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): A two-year field study. Plants 2024, 13, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavidas, I.; Ntatsi, G.; Vougeleka, V.; Karkanis, A.; Ntanasi, T.; Saitanis, C.; Agathokleous, E.; Ropokis, A.; Sabatino, L.; Tran, F.; et al. Agronomic practices to increase the yield and quality of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): A systematic review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdino, A.C.S.; de Freitas, M.B.; de Borba, M.C.; Stadnik, M.J. Phenolic and flavonoid content in roots and hypocotyls of resistant and susceptible bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) during early stage of colonization by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Phaseoli. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2021, 46, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.F.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.F.; Blair, M.W.; Wang, X.M.; Ge, W.D.; Zhu, Z.D.; Wang, S.M. Salicylic acid enhances resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Phaseoli in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 33, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Borba, M.C.; de Freitas, M.B.; Stadnik, M.J. Ulvan enhances seedling emergence and reduces Fusarium wilt severity in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Crop Prot. 2019, 118, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, B. Root rot of common bean in Zanjan, Iran: Major pathogens and yield loss estimates. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2008, 37, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Toledo-Souza, E.D.; da Silveira, P.M.; Café-Filho, A.C.; Junior, M.L. Fusarium wilt incidence and common bean yield according to the preceding crop and the soil tillage system. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2012, 47, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Jiang, G.; Wei, Z.; Sáez-Sandino, T.; Gao, M.; Liu, H.; Xiong, C. Plant pathogens, microbiomes, and soil health. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Mena, R.A.; Stoorvogel, J.J.; García-Bastidas, F.; Salacinas-Niez, M.; Kema, G.H.J.; Sandoval, J.A. Evaluating the potential of soil management to reduce the effect of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Cubense in banana (Musa AAA). Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 2021, 160, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petito, M.; Barca, E.; Pagnani, G.; Ranghetti, L.; Messori, F.; Antonucci, L.; Occhipinti, N.; Lorenzo, A.; Pisante, M. A geospatial framework for soil characterization: Integrating multitemporal remote sensing with advanced statistical methods. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MiPAAFT Gazzetta Ufficiale Supplemento Ordinario No. 248 Del 21/10/1999, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca Dello Stato, Rome, Italy. Methods VII.3 and XIV.2 + XIV.3. 1999. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- McKinney, H.H. Influence of soil temperature and moisture on infection of wheat seedlings by Helminthosporium sativum. J. Agric. Res. 1923, 26, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoonhoven, A. Standard System for Evaluation of Bean Germplasm; CIAT, Ed.; CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid dna isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.J.W.T.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: NewYork, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gamon, J.A.; Peñuelas, J.; Field, C.B. A narrow-waveband spectral index that tracks diurnal changes in photosynthetic efficiency. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 41, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Filella, I.; Gamon, J.A. Assessment of photosynthetic radiation-use efficiency with spectral reflectance. New Phytol. 1995, 131, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, P.; Yadav, R.K.; Manandhar, H.K.; Parajulee, M.N. Management of root rot (Rhizoctonia solani Kühn) of common bean using host resistance and consortia of chemicals and biocontrol agents. Biology 2025, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Landa, B.B.; Méndez-Rodríguez, M.A.; Jiménez-Díaz, R.M. Quantitative modeling of the effects of temperature and inoculum density of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Ciceris races 0 and 5 on development of Fusarium wilt in chickpea cultivars. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatch, E.W.; du Toit, L.J. Limestone-mediated suppression of Fusarium wilt in spinach seed crops. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanubile, A.; Muppirala, U.K.; Severin, A.J.; Marocco, A.; Munkvold, G.P. Transcriptome profiling of soybean (Glycine max) roots challenged with pathogenic and non-pathogenic isolates of Fusarium oxysporum. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byamukama, E.; Robertson, A.E.; Nutter, F.W. Quantifying the within-field temporal and spatial dynamics of bean pod mottle virus in soybean. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuerger, A.C.; Mitchell, D.J. Effects of temperature, hydrogen ion concentration, humidity, and light quality on disease caused by Fusarium solani f. sp. Phaseoli in mung bean. Can. J. Bot. 1992, 70, 1798–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K. Nutrient management for sustainable dry bean production in the tropics. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2002, 33, 1537–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Moreira, A.; Coelho, A.M. Nutrient uptake in dry bean genotypes. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2012, 43, 2289–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Sabagh, A.E.L.; Erman, M.; Fahad, S.; Islam, T.; Bhatt, R.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Nutrient management for improving abiotic stress tolerance in legumes of the family Fabaceae. In The Plant Family Fabaceae; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 393–415. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, K.M.; Brenner, T.; Jacobsen, B.J. Temperature effects on the interactions of sugar beet with Fusarium yellows caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Betae. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 37, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.B.; Li, S.D.; Ren, Q.; Xu, J.L.; Lu, X.; Sun, M.H. Biology and applications of Clonostachys rosea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Rondelli, V.; Martelli, R.; Falsone, G.; Lupia, F.; Barbanti, L. Management zones delineation through clustering techniques based on soils traits, NDVI data, and multiple year crop yields. Agriculture 2022, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, P.; Ferraro, M.B.; Martella, F. Hierarchical clustering. In An Introduction to Clustering with R; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 9–73. [Google Scholar]

| Exp. F1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| MUZs | Soil Sampling Points | Hectares |

| 1 | 9 | 1.37 |

| 2 | 9 | 3.26 |

| 3 | 9 | 2.85 |

| Total | 27 | 7.48 |

| Exp. F2 | ||

| MUZs | Soil Sampling Points | Hectares |

| 1 | 9 | 0.49 |

| 2 | 9 | 2.99 |

| 3 | 9 | 2.23 |

| Total | 27 | 5.71 |

| Experiment | MUZs | Sand (g/kg) | Silt (g/kg) | Clay (g/kg) | OC (g/kg) | N (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. F1 | ||||||

| 1 | 284.67 b | 346.78 a | 368.56 a | 9.52 a | 1.06 a | |

| 2 | 291.89 ab | 354.44 a | 353.67 ab | 9.18 ab | 0.99 a | |

| 3 | 314.44 a | 359.78 a | 325.78 b | 8.79 b | 0.98 a | |

| Exp. F2 | ||||||

| 1 | 141.89 a | 417.11 a | 441.00 a | 8.31 a | 1.19 a | |

| 2 | 188.22 a | 437.44 a | 374.33 b | 8.04 b | 1.06 b | |

| 3 | 222.22 b | 431.33 a | 346.44 b | 7.96 b | 1.03 b |

| Exp. F1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square Test | MUZs | ||||

| Chi-Square | Prob > Chi-Square | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Incidence (%) | 33.25 | 0.05 | 14.07 b | 8.64 b | 63.95 a |

| Severity (%) | 39.19 | 0.05 | 3.92 b | 2.33 b | 28.01 a |

| Exp. F2 | |||||

| Chi Square Test | MUZs | ||||

| Chi-Square | Prob > Chi-Square | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Incidence (%) | 28.86 | 0.05 | 44.69 b | 48.88 b | 88.15 a |

| Severity (%) | 34.37 | 0.05 | 14.07 b | 14.02 b | 58.18 a |

| Exp. F1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUZs | Total Pod (n.) | Symptomatic Pods | Marketable Pods | ||

| Number | Weight (g m2) | Number | Weight (g m2) | ||

| 1 | 252 a | 7 b | 16.18 b | 243 a | 533.23 a |

| 2 | 251 a | 11 b | 19.87 b | 240 a | 500.00 b |

| 3 | 244 b | 53 a | 135.15 a | 191 b | 438.99 c |

| Exp. F2 | |||||

| MUZs | Total Pod (n.) | Symptomatic Pods | Marketable Pods | ||

| Number | Weight (g m2) | Number | Weight (g m2) | ||

| 1 | 290 a | 22 b | 57.43 b | 267 a | 681.24 a |

| 2 | 284 b | 27 b | 49.49 b | 257 b | 647.59 b |

| 3 | 267 c | 66 a | 234.54 a | 201 c | 544.05 c |

| Colony Typology * | Colony Isolation ** (%) | Fungal Species | Identity of Alignment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GB2 | 0.74 | Clonostachys rosea | 99 |

| GB4 | 0.74 | Aspergillus melleus | 99 |

| GB7 | 0.74 | Clonostachys rosea | 99 |

| GB8 | 97.78 | Fusarium oxysporum | 100 |

| sterile | 0.00 | / | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagnani, G.; Calzarano, F.; Antonucci, L.; Petito, M.; Di Marco, S.; Osti, F.; Nematpour, A.; Lorenzo, A.; Occhipinti, N.; Stagnari, F.; et al. Mapping Yield and Fusarium Wilt on Green Bean Combining Vegetation Indices in Different Management Zones. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122848

Pagnani G, Calzarano F, Antonucci L, Petito M, Di Marco S, Osti F, Nematpour A, Lorenzo A, Occhipinti N, Stagnari F, et al. Mapping Yield and Fusarium Wilt on Green Bean Combining Vegetation Indices in Different Management Zones. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122848

Chicago/Turabian StylePagnani, Giancarlo, Francesco Calzarano, Lisa Antonucci, Matteo Petito, Stefano Di Marco, Fabio Osti, Afsaneh Nematpour, Alfredo Lorenzo, Nausicaa Occhipinti, Fabio Stagnari, and et al. 2025. "Mapping Yield and Fusarium Wilt on Green Bean Combining Vegetation Indices in Different Management Zones" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122848

APA StylePagnani, G., Calzarano, F., Antonucci, L., Petito, M., Di Marco, S., Osti, F., Nematpour, A., Lorenzo, A., Occhipinti, N., Stagnari, F., & Pisante, M. (2025). Mapping Yield and Fusarium Wilt on Green Bean Combining Vegetation Indices in Different Management Zones. Agronomy, 15(12), 2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122848