Investigation of the Migration of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Soil–Millet System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. High-Through qPCR for ARGs

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Alpha-Diversity of ARGs in Soil–Millet System

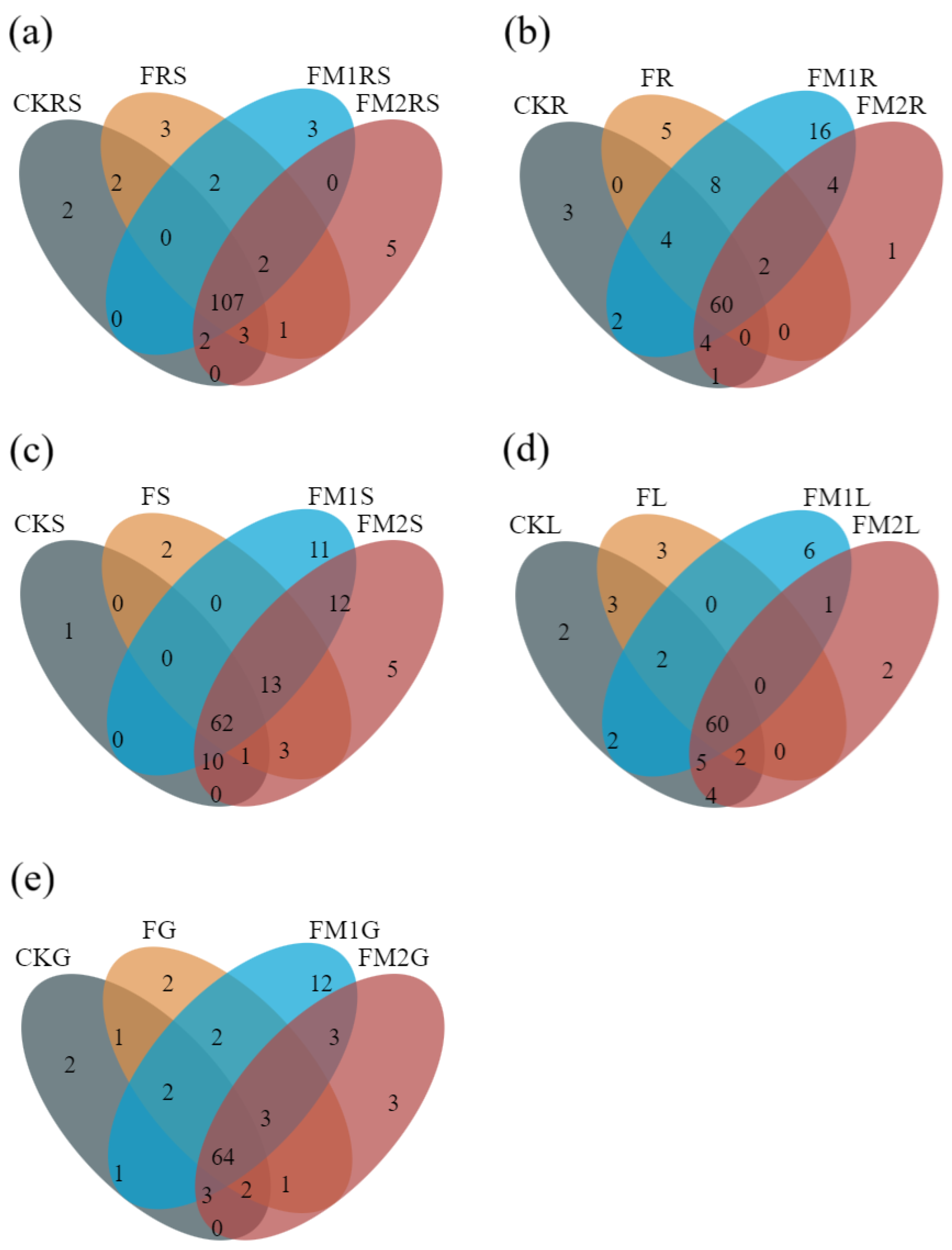

3.2. Venn Diagram of ARGs in Soil–Millet System

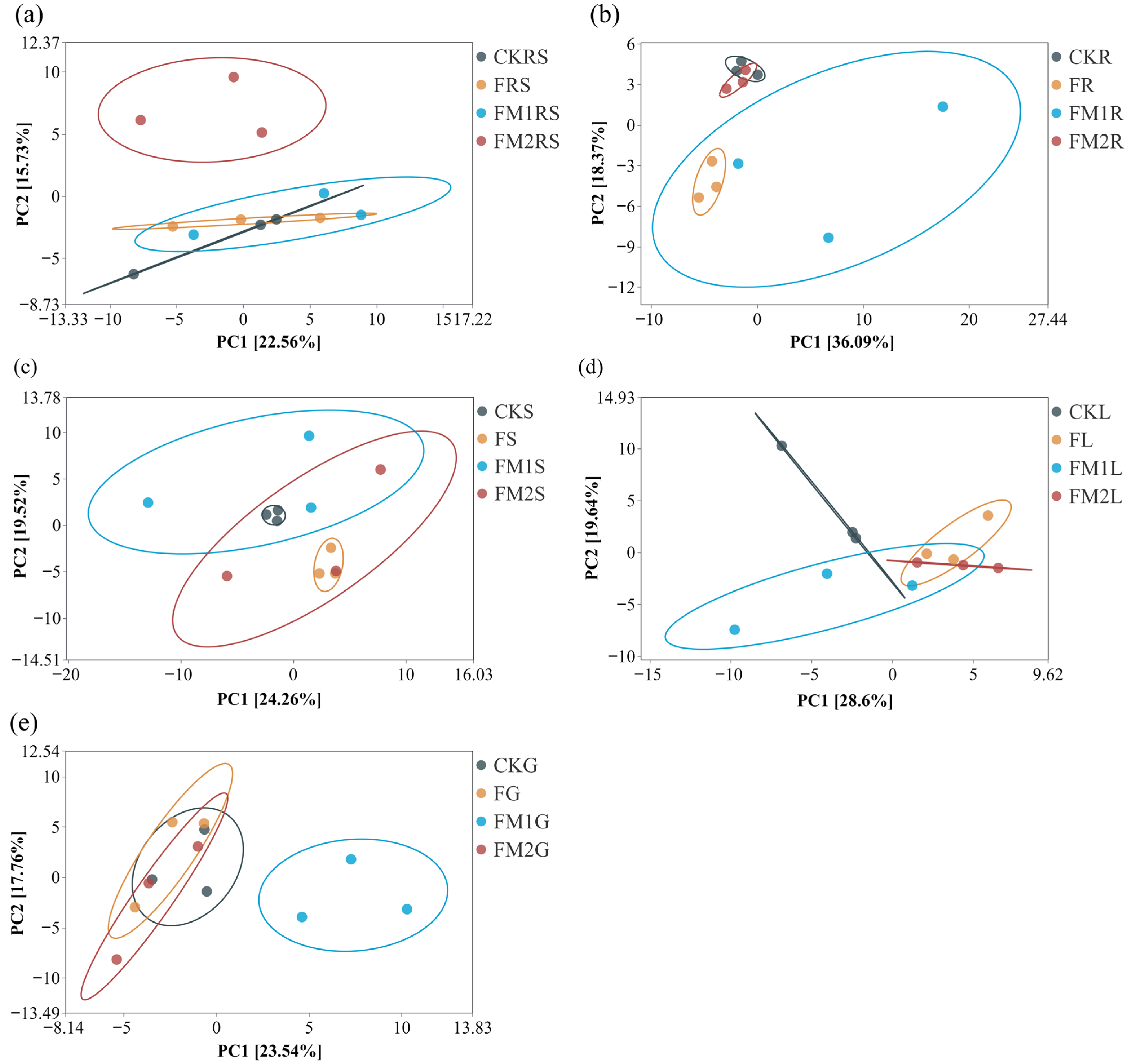

3.3. Beta-Diversity of ARGs in Soil–Millet System

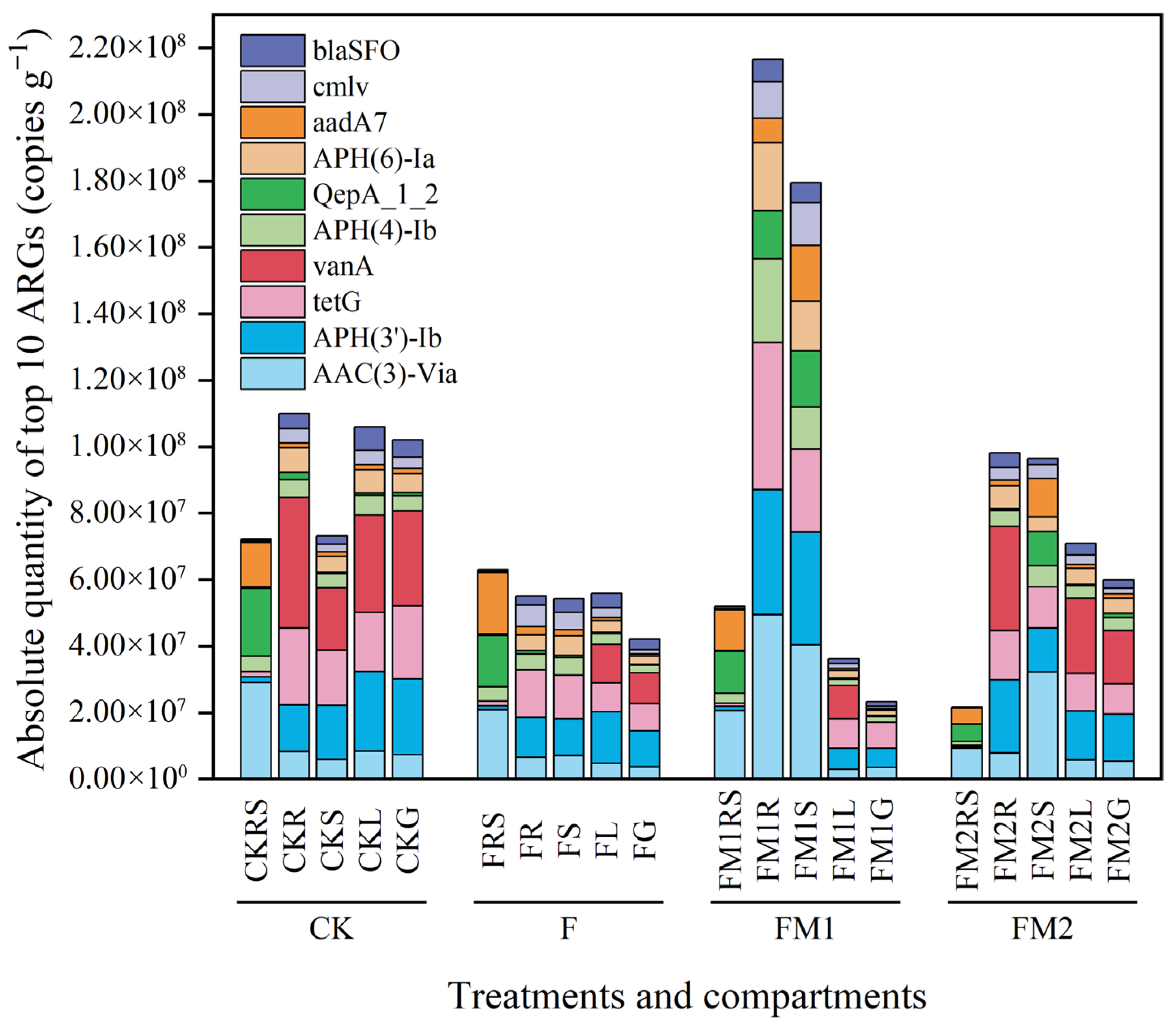

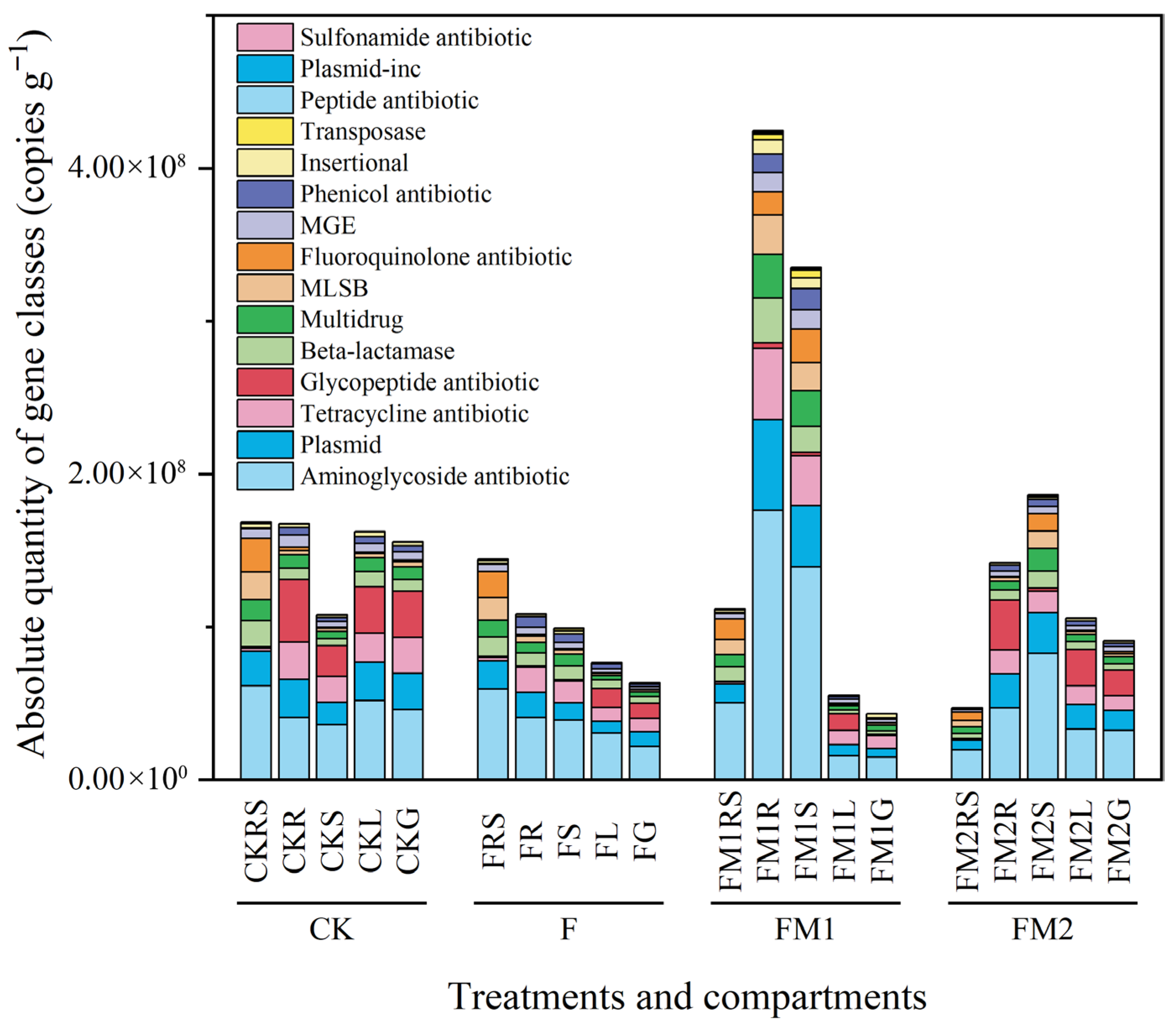

3.4. Absolute Abundance of ARGs in the Soil–Millet System

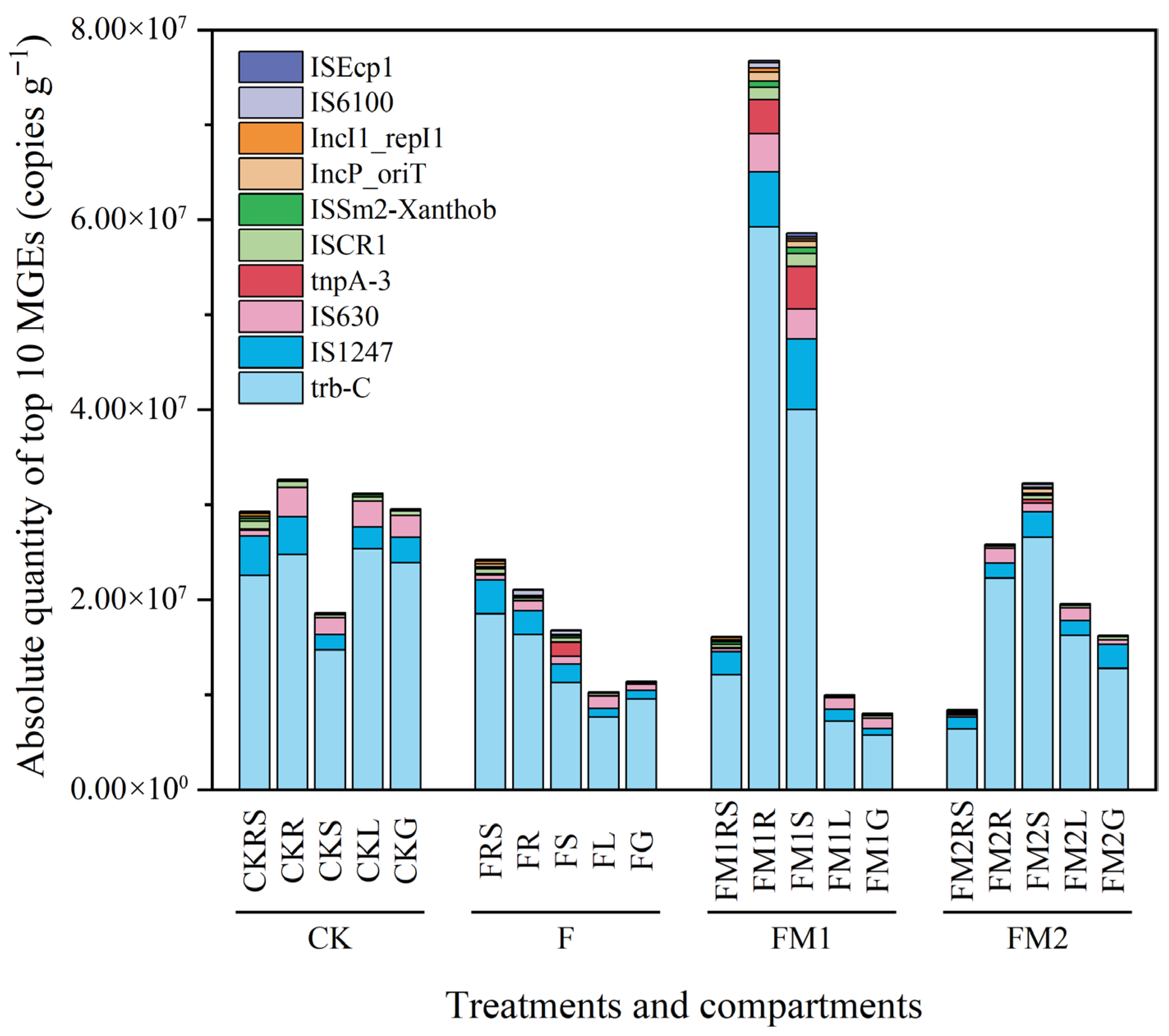

3.5. Absolute Abundance of MGEs in the Soil–Millet System

3.6. Absolute Abundance of Gene Families in the Soil–Millet System

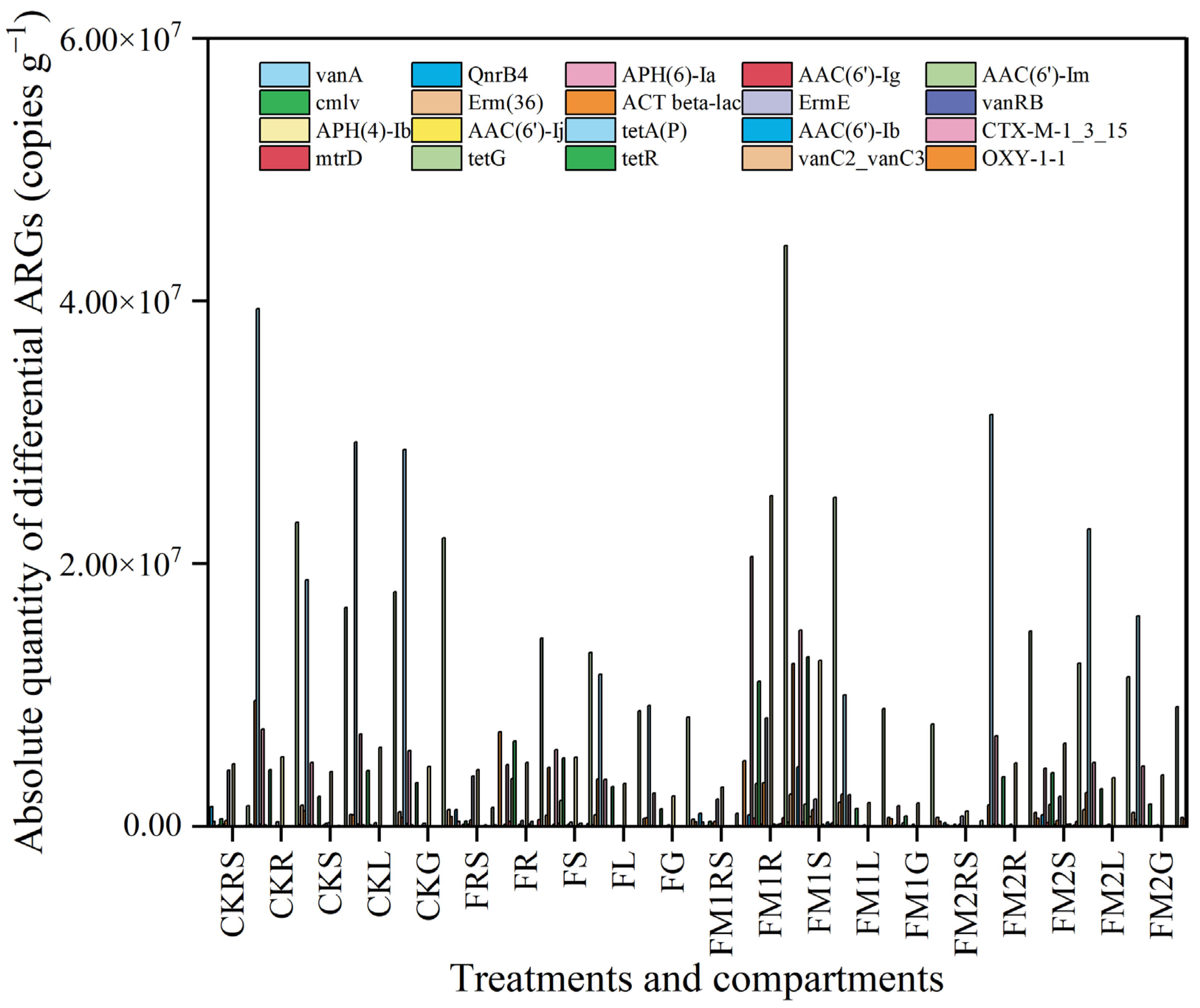

3.7. Differential ARGs

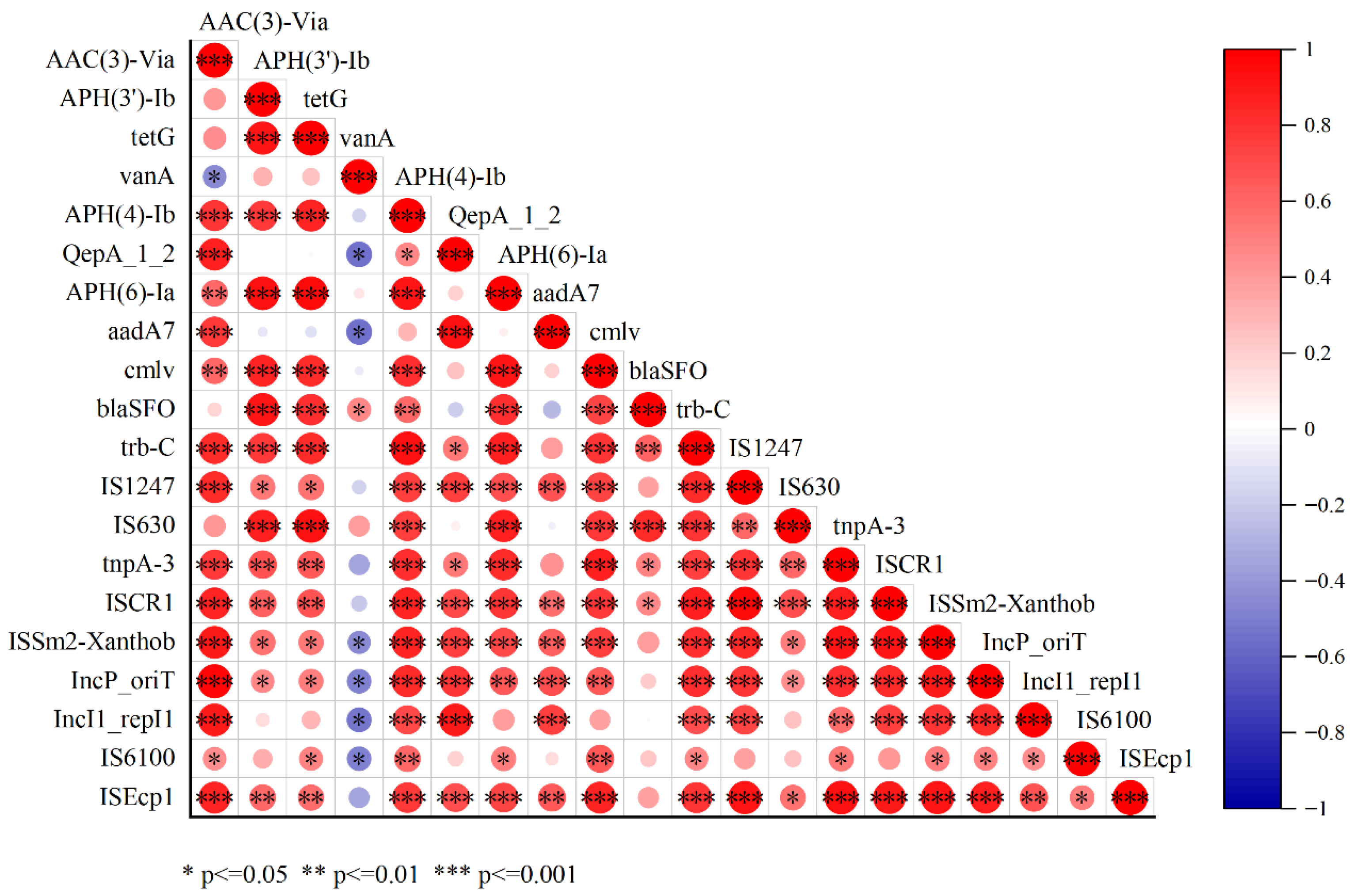

3.8. Correlation of ARGs and MGEs

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Fertilization on the Distribution and Migration of ARGs and MGEs in Soil–Millet System

4.2. The Distribution of ARGs and MGEs in Soil–Millet System and Their Correlation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, L.J.; Ying, G.G.; Liu, S.; Zhang, R.Q.; Lai, H.J.; Chen, Z.F.; Pan, C.G. Excretion masses and environmental occurrence of antibiotics in typical swine and dairy cattle farms in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 444, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmah, A.K.; Meyer, M.T.; Boxall, A.B. A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 725–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Syed, M. Antibiotics: Past, Present and Future. J. Biomol. Res. Ther. 2016, 5, 1000e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, H.; Schmitt, H.; Smalla, K. Antibiotic resistance gene spread due to manure application on agricultural fields. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puckowski, A.; Mioduszewska, K.; Lukaszewicz, P.; Borecka, M.; Caban, M.; Maszkowska, J.; Stepnowski, P. Bioaccumulation and analytics of pharmaceutical residues in the environment: A review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 127, 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.L.; Coque, T.M.; Baquero, F. What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, R.L.; Collignon, P.; Larsson, D.G.; McEwen, S.A.; Li, X.Z.; Gaze, W.H.; Reid-Smith, R.; Timinouni, M.; Graham, D.W.; Topp, E. The scourge of antibiotic resistance: The important role of the environment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jechalke, S.; Schreiter, S.; Wolters, B.; Dealtry, S.; Heuer, H.; Smalla, K. Widespread dissemination of class 1 integron components in soils and related ecosystems as revealed by cultivation-independent analysis. Front Microbiol. 2014, 4, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Kim, O.S.; Chai, B.; Yang, L.; Stedtfeld, T.M.; Hong, S.G.; Kim, D.; Lim, H.S.; Hashsham, S.A.; et al. Influence of Soil Characteristics and Proximity to Antarctic Research Stations on Abundance of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 12621–12629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, G. Burden of infectious diseases and bacterial antimicrobial resistance in China: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 2024, 43, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruden, R.A.; Pei, R.; Storteboom, H. Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants: Studies in northern Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 7445–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.L.; Oda, Y.; Grewal, S.; Morrison, M.; Michel, F.C.; Yu, Z.T. Persistence of resistanceto erythromycin and tetracycline in swine manure during simulatedcomposting and lagoon treatments. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 63, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binh, C.T.; Heuer, H.; Kaupenjohann, M.; Smalla, K. Piggery manure used for soil fertilization is a reservoir for transferable antibiotic resistance plasmids. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binh, C.T.; Heuer, H.; Kaupenjohann, M.; Smalla, K. Diverse aadA gene cassettes on class 1 integrons introduced into soil via spread manure. Res. Microbiol. 2009, 160, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedje, J.M.; Wang, F.; Manaia, C.M.; Virta, M.; Sheng, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, T.; Topp, E. Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Human-Impacted Environment: A One Health Perspective. Pedosphere 2019, 29, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Domingues, S.; Da Silva, G.J. Manure as a Potential Hotspot for Antibiotic Resistance Dissemination by Horizontal Gene Transfer Events. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checcucci, A.; Trevisi, P.; Luise, D.; Modesto, M.; Blasioli, S.; Braschi, I.; Mattarelli, P. Exploring the Animal Waste Resistome: The Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Through the Use of Livestock Manure. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.Q.; Wei, B.; Ou-Yang, W.Y.; Huang, F.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.J.; Zhu, Y.G. Antibiotic resistome and its association with bacterial communities during sewage sludge composting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 7356–7363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarczuk, K.; Markowicz, A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. The urgent need for risk assessment on the antibiotic resistance spread via sewage sludge land application. Environ. Int. 2016, 87, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.L.; An, X.L.; Zheng, B.X.; Ma, Y.B.; Su, J.Q. Long-term organic fertilization increased antibiotic resistome in phyllosphere of maize. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, Y.C.; Li, B.; Zhang, T.; Scott, A.; Murray, R.; Sabourin, L.; Marti, R.; Topp, E. Impact of dairy manure pre-application treatment on manure composition, soil dynamics of antibiotic resistance genes, and abundance of antibiotic-resistance genes on vegetables at harvest. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 581–582, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; An, X.; Li, H.; Su, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.G. Long-term field application of sewage sludge increases the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in soil. Environ. Int. 2016, 92–93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, F.; Rizzotti, L.; Felis, G.E.; Torriani, S. Horizontal gene transfer among microorganisms in food: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Food Microbiol. 2014, 42, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezanson, G.S.; MacInnis, R.; Potter, G.; Hughes, T. Presence and potential for horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance in oxidase-positive bacteria populating raw salad vegetables. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 127, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Ryser, E.T.; Li, H.; Zhang, W. Bacterial community assembly and antibiotic resistance genes in the lettuce-soil system upon antibiotic exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yu, K.; He, Y. The dynamics and transmission of antibiotic resistance associated with plant microbiomes. Environ. Int. 2023, 176, 107986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.L.; Cui, H.L.; Su, J.Q.; Penuelas, J.; Zhu, Y.G. Antibiotic Resistomes in Plant Microbiomes. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, F.; Matamoros, V.; Bayona, J.M.; Berendonk, T.U.; Elsinga, G.; Hornstra, L.M.; Pina, B. Antibiotic resistance gene distribution in agricultural fields and crops. A soil-to-food analysis. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, J.; Duan, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q.; Liu, M.; Xue, C.; Guo, S.; Shen, Q.; et al. Long-term manure inputs induce a deep selection on agroecosystem soil antibiotic resistome. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Teng, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; He, C.; Li, B.; Zhou, T.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Li, H. Exploring potential ecological risks of antibiotic–resistance genes in soil–plant systems caused by manure application. Sustain. Horiz. 2025, 14, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Hu, H.W.; Chen, Q.L.; Singh, B.K.; Yan, H.; Chen, D.; He, J.Z. Transfer of antibiotic resistance from manure-amended soils to vegetable microbiomes. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H.; Qiao, M.; Chen, Z.; Su, J.Q.; Zhu, Y.G. Antibiotic resistance genes in manure-amended soil and vegetables at harvest. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.J.; Li, H.Z.; Xu, J.; Gillings, M.R.; Zhu, Y.G. Sewage Sludge Promotes the Accumulation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Tomato Xylem. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10796–10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Zheng, N.; An, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, S.; Ji, Y.; Li, N. The effects of cadmium-copper stress on the accumulation of antibiotic-resistance genes in soil and pakchoi leaves. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 191, 109362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Luo, B.; Cao, T.; Bai, T.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Xie, J.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; et al. Livestock manure-based organic fertilization facilitates the transmission of antibiotic resistance genes across the soil-onion continuum: A significant contribution from root exudates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 209, 109910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregi, L.; Epelde, L.; Alkorta, I.; Garbisu, C. Antibiotic Resistance in Agricultural Soil and Crops Associated to the Application of Cow Manure-Derived Amendments From Conventional and Organic Livestock Farms. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 633858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.M. Progresses in stress tolerance and field cultivation studies of orphan cereals in China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2019, 52, 3943–3949. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.W.; Zhao, J.F.; Wang, G.H.; Li, Y.F.; Zhao, G.Y.; Yan, X.F. Effects of different density and row spacing on agronomic traits and yield of spring millet. J. Shanxi Agric. Sci. 2019, 47, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stedtfeld, R.D.; Guo, X.P.; Stedtfeld, T.M. Primer set 2.0 for highly parallel qPCR array targeting antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yao, Q.; Liu, J.J. Profiles of antibiotic resistome with animal manure application in black soils of northeast China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Kim, Y.M. Distribution of quinolone and macrolide resistance genes and their co-occurrence with heavy metal resistance genes in vegetable soils with long-term application of manure. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 44, 3343–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahube, T.O.; Marti, R.; Scott, A.; Tien, Y.C.; Murray, R.; Sabourin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Duenk, P.; Lapen, D.R.; Topp, E. Impact of fertilizing with raw or anaerobically digested sewage sludge on the abundance of antibiotic-resistant coliforms, antibiotic resistance genes, and pathogenic bacteria in soil and on vegetables at harvest. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 6898–6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marti, R.; Scott, A.; Tien, Y.C.; Murray, R.; Sabourin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Topp, E. Impact of manure fertilization on the abundance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and frequency of detection of antibiotic resistance genes in soil and on vegetables at harvest. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5701–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.G.; Liu, F.; Liu, M.; Cheng, R.H.; Xia, E.J.; Diao, X.M. Current status and future prospective of foxtail millet production and seed industry in China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2021, 54, 459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Wu, W.F.; Wu, C.Y.; Hu, Y.; Xiang, Q.; Li, G.; Lin, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.G. Seeds Act as Vectors for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Dissemination in a Soil-Plant Continuum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 21358–21369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant-microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.R.; Lundberg, D.S.; Del Rio, T.G.; Tringe, S.G.; Dangl, J.L.; Mitchell-Olds, T. Host genotype and age shape the leaf and root microbiomes of a wild perennial plant. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Schlaeppi, K.; Spaepen, S.; Ver Loren van Themaat, E.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorholt, J.A. Microbial life in the phyllosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, F.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Fu, Y.; Xiang, L.; Sheng, H.; Li, Z.; Hashsham, S.A.; Jiang, X.; Tiedje, J.M. Transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from soil to rice in paddy field. Environ. Int. 2024, 191, 108956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Yuan, J.; Hong, W.D.; Niu, G.Q.; Zou, X.; Yang, X.P.; Shen, Q.; Zhao, F.J. Prevalent and highly mobile antibiotic resistance genes in commercial organic fertilizers. Environ. Int. 2022, 162, 107157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, X.Y.; Hu, X.J.; Ling, W.T. Migration and reduction of antibiotic resistance genes in soil-vegetable systems. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2025, 44, 605–615. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Huang, R.; Cui, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Mao, D.; Luo, Y.; Ren, H. Antibiotic Resistance Gene-Carrying Plasmid Spreads into the Plant Endophytic Bacteria using Soil Bacteria as Carriers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 10462–10470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Huang, D.; Du, L.; Song, B.; Yin, L.; Chen, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, R.; Huang, H.; Zeng, G. Antibiotic resistance in soil-plant systems: A review of the source, dissemination, influence factors, and potential exposure risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sui, Q.; Tong, J.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wei, Y. Soil types influence the fate of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes following the land application of sludge composts. Environ. Int. 2018, 118, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Chen, Q.; Chen, S.; Zhu, Y.G. Does organically produced lettuce harbor higher abundance of antibiotic resistance genes than conventionally produced? Environ. Int. 2017, 98, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Zhang, X.; Maciel-Guerra, A.; Babaarslan, K.; Dong, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, Y.; Renney, D.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; et al. Convergence of resistance and evolutionary responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica co-inhabiting chicken farms in China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Chemical Fertilizer | Manure | Total Nutrients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P2O5 | K2O | N | P2O5 | K2O | N | P2O5 | K2O | |

| CK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 225 | 112.5 | 135 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225 | 112.5 | 135 |

| FM1 | 225 | 112.5 | 135 | 130 | 90 | 285 | 355 | 202.5 | 420 |

| FM2 | 225 | 112.5 | 135 | 260 | 180 | 570 | 485 | 682.5 | 705 |

| ACE | Chao1 | Simpson | Shannon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKRS | 100.49 a | 102.83 a | 11.89 ab | 4.40 b |

| FRS | 109.45 a | 121.27 a | 12.83 a | 4.51 a |

| FM1RS | 116.50 a | 121.38 a | 12.34 a | 4.51 a |

| FM2RS | 103.02 a | 99.28 a | 11.04 b | 4.40 b |

| CKR | 63.89 b | 66.33 b | 8.70 b | 3.87 bc |

| FR | 70.25 b | 64.92 b | 9.24 b | 4.07 b |

| FM1R | 92.36 a | 94.31 a | 14.62 a | 4.61 a |

| FM2R | 59.24 b | 60.87 b | 8.40 b | 3.77 c |

| CKS | 78.16 a | 93.88 a | 9.36 b | 3.93 c |

| FS | 75.77 a | 72.94 a | 14.02 a | 4.52 a |

| FM1S | 82.31 a | 86.06 a | 13.24 a | 4.49 a |

| FM2S | 83.94 a | 81.03 a | 10.48 ab | 4.24 b |

| CKL | 47.70 a | 44.39 a | 9.50 a | 3.95 ab |

| FL | 51.41 a | 41.38 a | 9.46 a | 3.91 ab |

| FM1L | 47.16 a | 50.11 a | 10.03 a | 4.03 a |

| FM2L | 41.88 a | 35.51 a | 8.93 a | 3.88 b |

| CKG | 51.57 b | 52.65 a | 9.05 a | 3.90 b |

| FG | 52.55 b | 74.46 a | 9.65 a | 3.94 b |

| FM1G | 62.79 a | 64.00 a | 11.41 a | 4.24 a |

| FM2G | 51.33 b | 51.02 a | 10.13 a | 4.00 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hua, J.; Xie, W.; Yang, Z.; He, L.; Wu, X.; Chen, D.; Zhou, H. Investigation of the Migration of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Soil–Millet System. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2849. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122849

Liu Z, Guo Z, Wang Z, Hua J, Xie W, Yang Z, He L, Wu X, Chen D, Zhou H. Investigation of the Migration of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Soil–Millet System. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2849. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122849

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhiping, Ziyuan Guo, Zongyi Wang, Jin Hua, Wenyan Xie, Zhenxing Yang, Liyan He, Xueping Wu, Deli Chen, and Huaiping Zhou. 2025. "Investigation of the Migration of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Soil–Millet System" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2849. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122849

APA StyleLiu, Z., Guo, Z., Wang, Z., Hua, J., Xie, W., Yang, Z., He, L., Wu, X., Chen, D., & Zhou, H. (2025). Investigation of the Migration of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Soil–Millet System. Agronomy, 15(12), 2849. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122849