Foliar Fertilization-Induced Rhizosphere Microbial Mechanisms for Soil Health Enhancement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Soil Sampling

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.2.2. Metagenomic Analysis of Soil Microbial Communities

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Bioinformatic Analyses

2.3.2. Calculation of the Soil Health Index (SHI)

3. Results

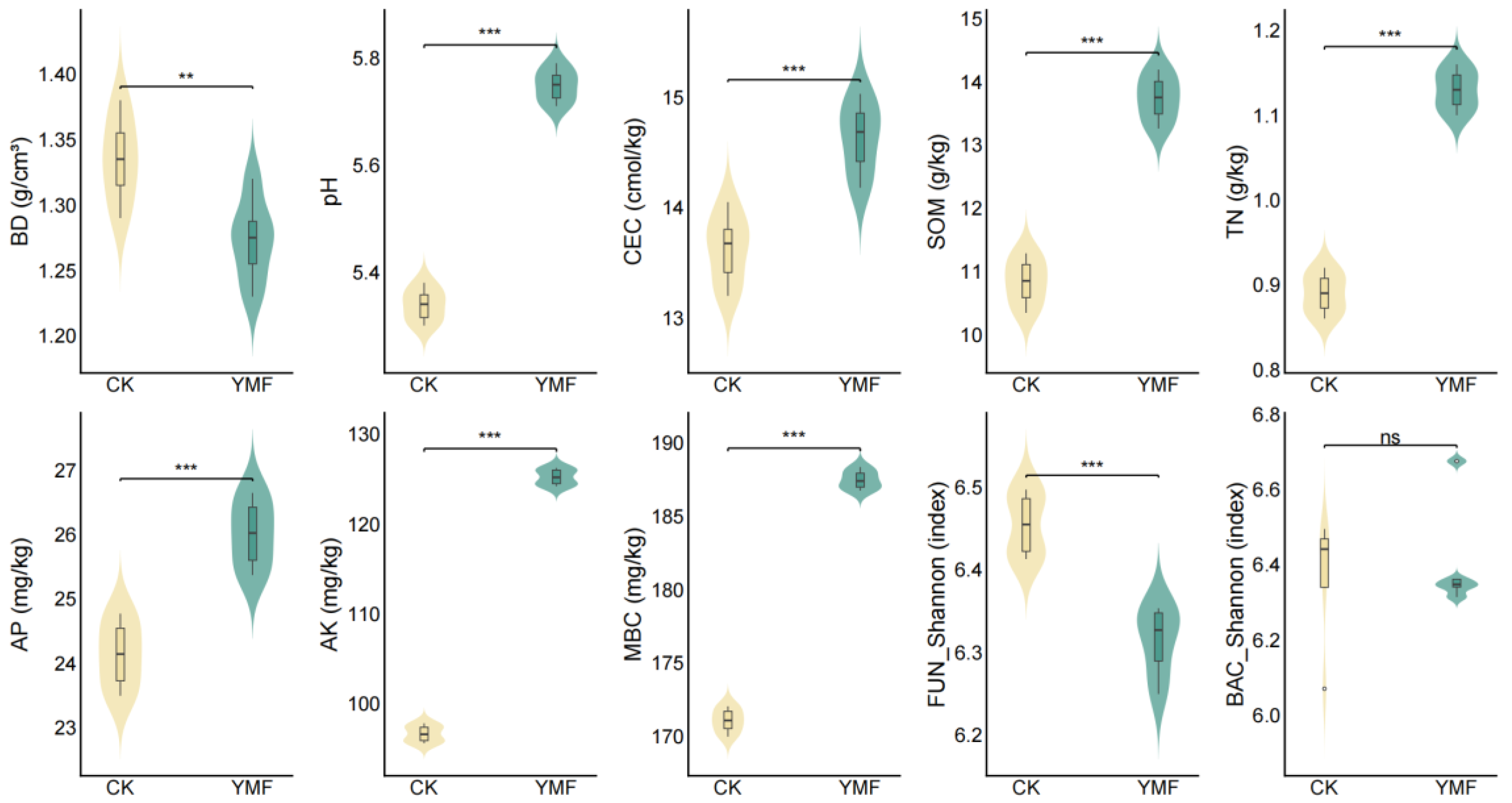

3.1. Physicochemical and Microbial Characteristics of Soil

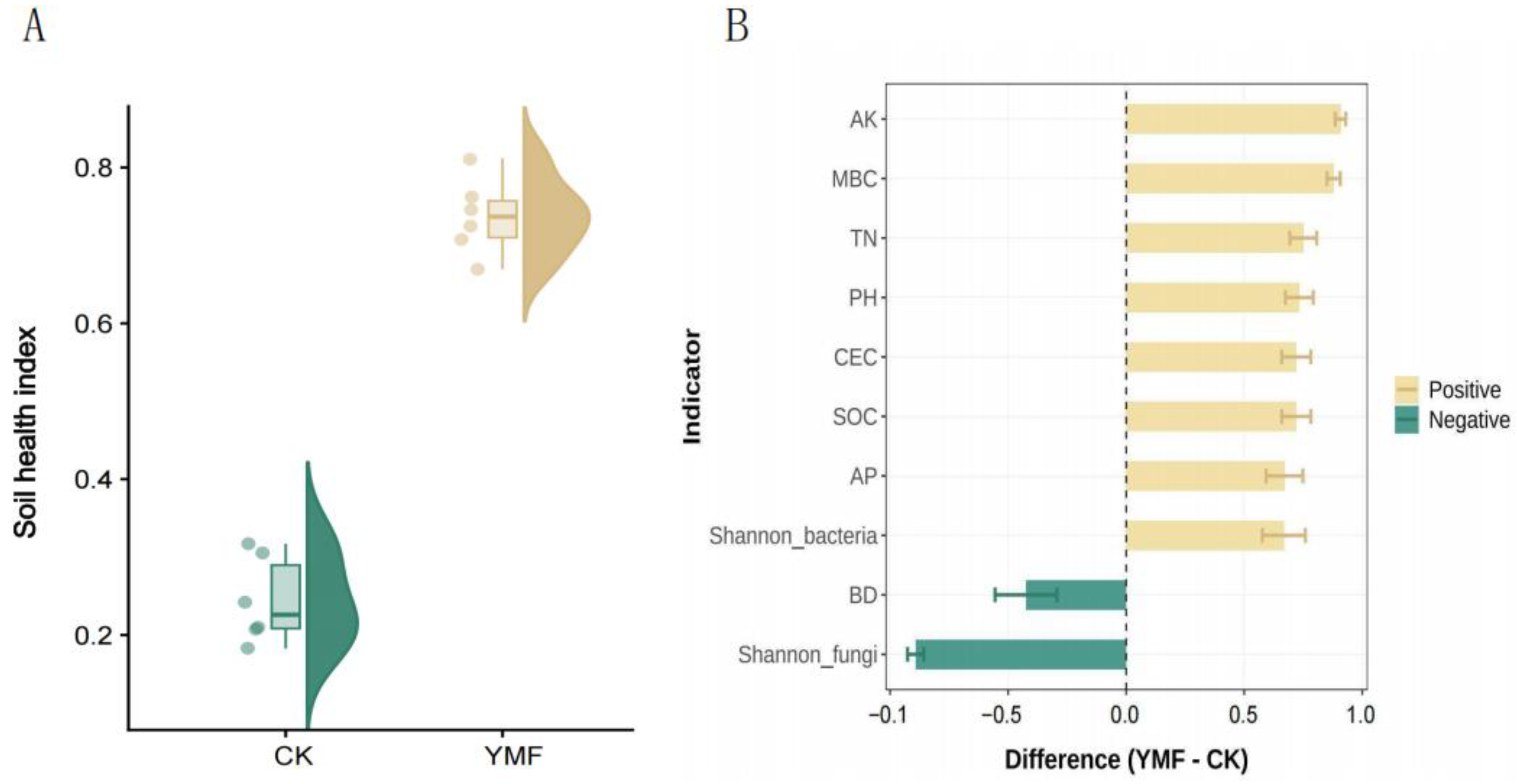

3.2. Soil Health Index (SHI) Analysis

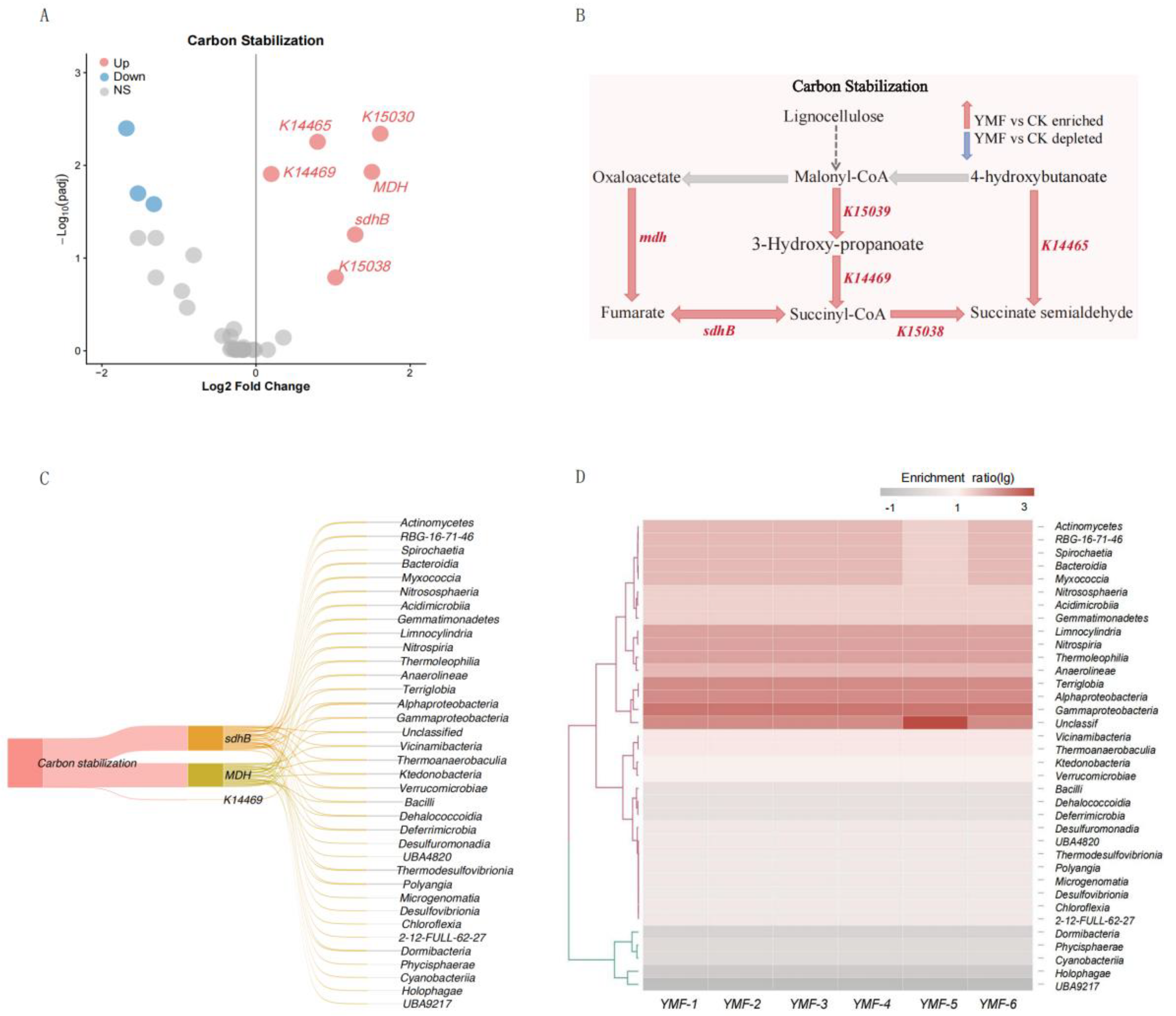

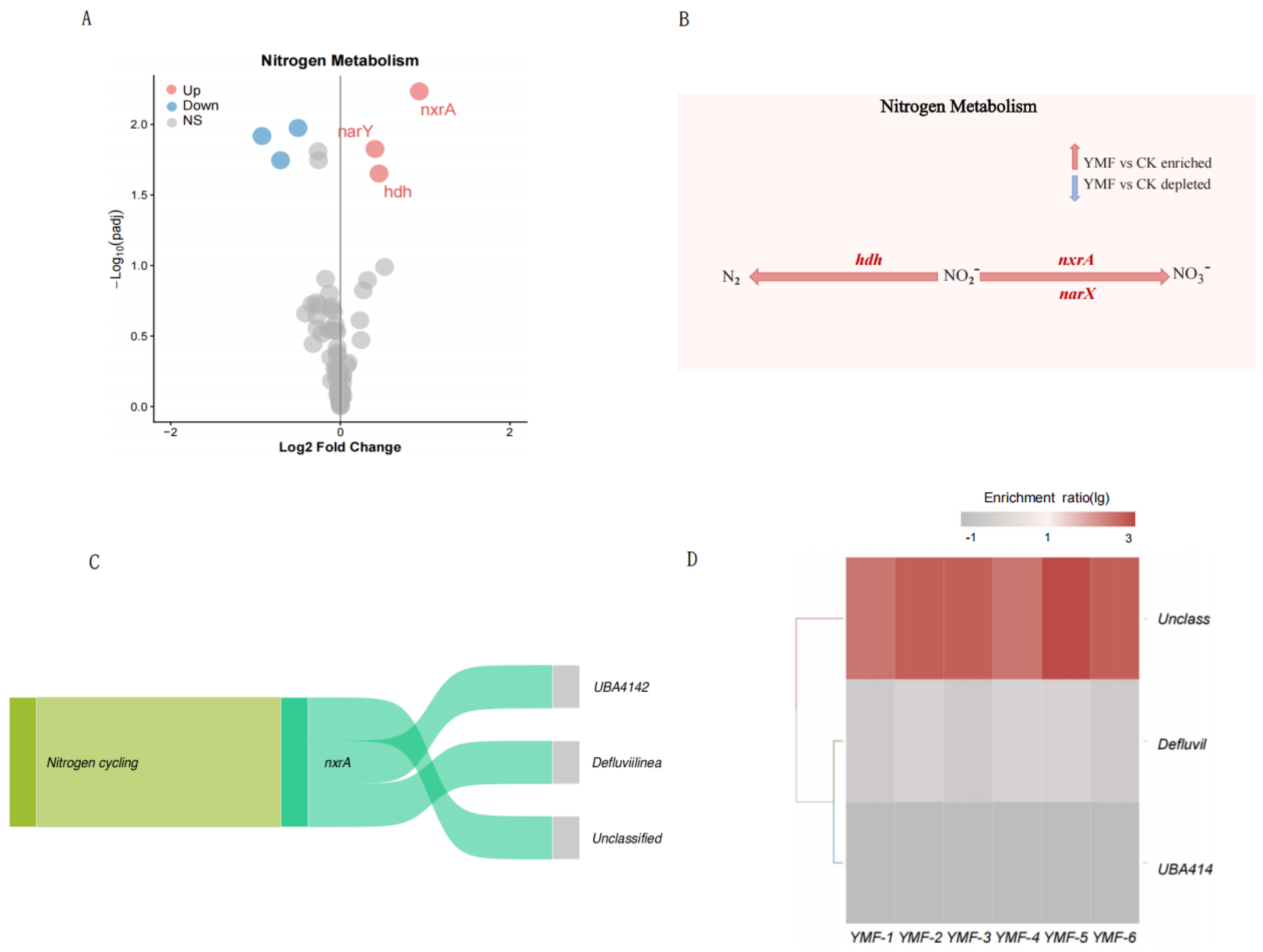

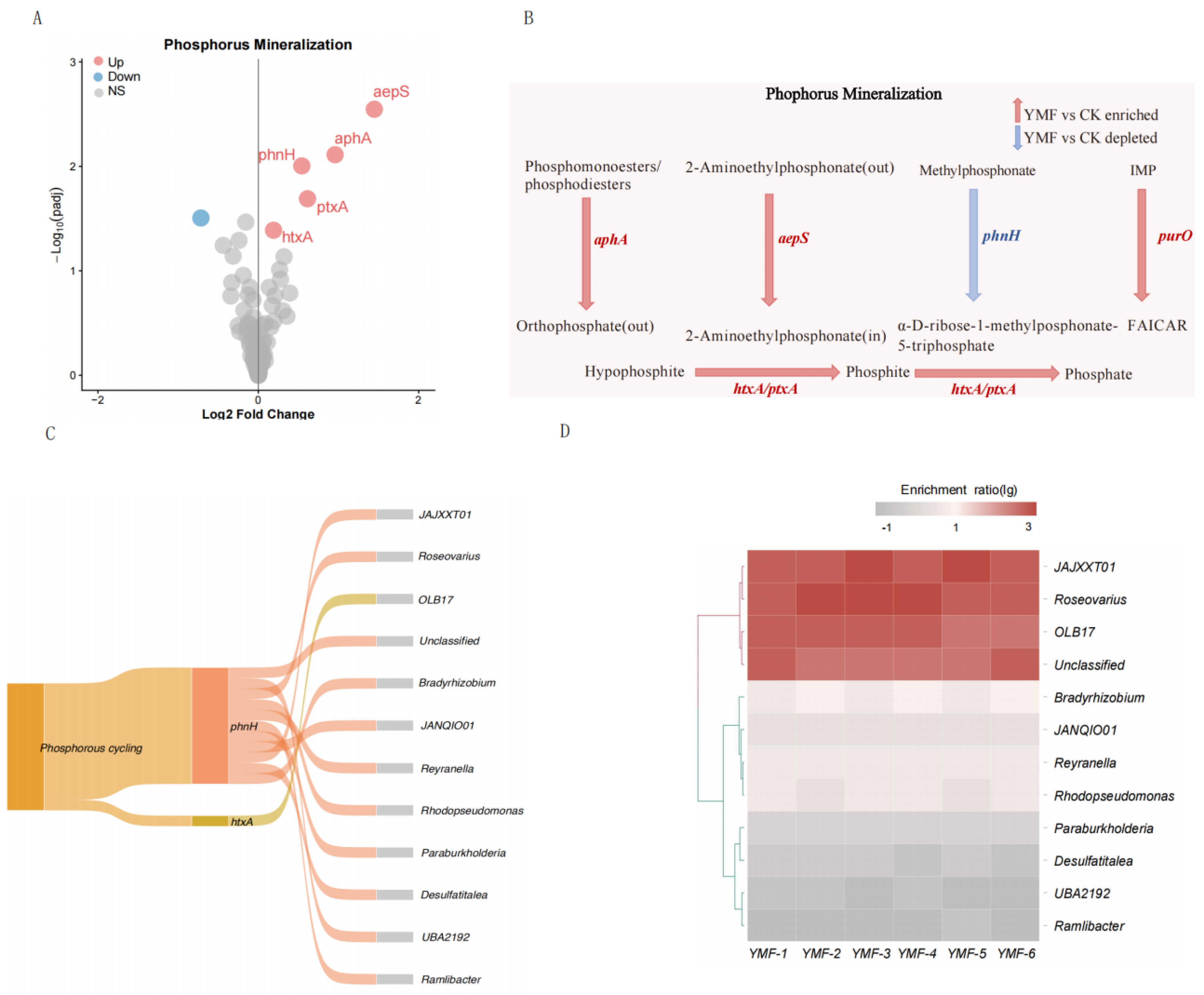

3.3. Differential Functional Gene Analysis and Taxonomic Annotation

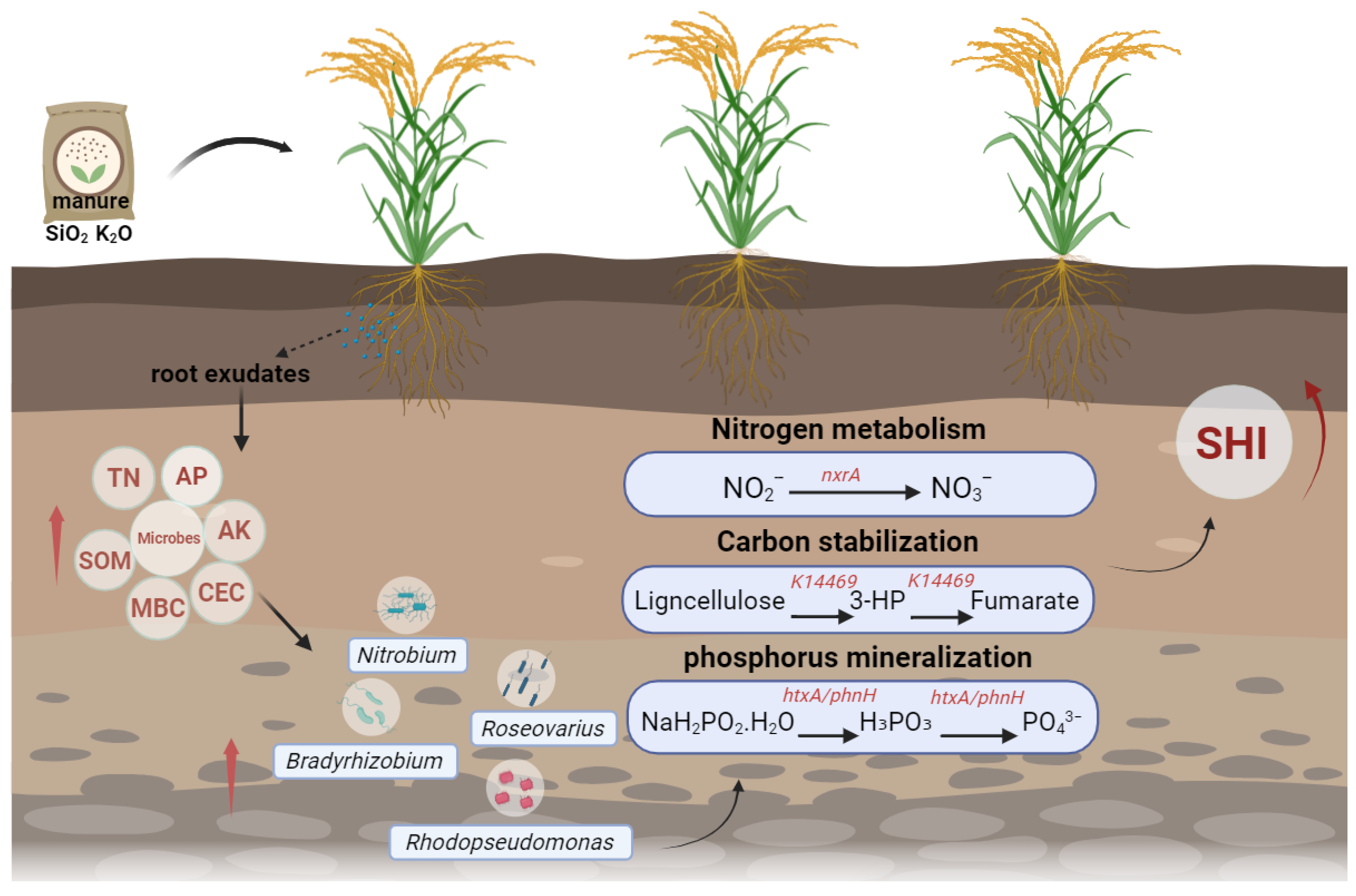

3.4. Foliar Fertilization–Mediated Mechanisms of C–N–P Cycling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doran, J.W.; Zeiss, M.R. Soil Health and Sustainability: Managing the Biotic Component of Soil Quality. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2000, 15, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibblewhite, M.G.; Ritz, K.; Swift, M.J. Soil Health in Agricultural Systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Ren, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, S. Soil health contributes to variations in crop production and nitrogen use efficiency. Nat. Food 2025, 6, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khambalkar, P.A.; Agrawal, S.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Yadav, S.S.; Sadawarti, M.J.; Singh, A.; Yadav, I.R.; Yadav, K.; Shivansh; Prasad, D.; et al. Sustainable Nutrient Management Balancing Soil Health and Food Security for Future Generations. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Ren, C.; Wang, C.; Cheng, L.; Xu, J.; Gu, B. Agricultural Management Practices in China Enhance Nitrogen Sustainability and Benefit Human Health. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Improving Nutrient Use Efficiencies with Foliar Applied Nutrients. Integr. Soils 2023, v190829. [Google Scholar]

- Balachandra, Y.; Tej, M.K.; Raju, S.J.; Reddy, B.J. Foliar Fertilization for Nutrient Use Efficiency. Int. J. Agric. Nutr. 2025, 7, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, M.; Kiran, A.; Ur Rehman, H.; Farooq, M.; Ijaz, N.H.; Nadeem, F.; Azeem, I.; Li, X.; Wakeel, A. Foliar Nutrition: Potential and Challenges under Multifaceted Agriculture. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 200, 104909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z.; Redmile-Gordon, M.; Liang, C.; Tang, C.; Guggenberger, G.; Yan, S.; Yin, L.; Peng, J.; et al. Microbial Metabolisms Determine Soil Priming Effect Induced by Organic Inputs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 209, 109885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Reich, P.B.; Jeffries, T.C.; Gaitan, J.J.; Encinar, D.; Berdugo, M.; Campbell, C.D.; Singh, B.K. Microbial Diversity Drives Multifunctionality in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.; Saharan, B.S. Microbial Dynamics in Soil: Impacts on Fertility, Nutrient Cycling, and Soil Properties for Sustainable Geosciences—People, Planet, and Prosperity. Arab. J. Geosci. 2025, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, N.; Franks, A.E.; Shentu, J.; Luo, Y.; Xu, J.; He, Y. Loss of Microbial Diversity Does Not Decrease γ-HCH Degradation but Increases Methanogenesis in Flooded Paddy Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 156, 108210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, V.; Brown, P.H. From Plant Surface to Plant Metabolism: The Uncertain Fate of Foliar-Applied Nutrients. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Fu, W.; Wang, G.; Ji, J.; Guan, C. Rice-Associated with Bacillus sp. DRL1 Enhanced Remediation of DEHP-Contaminated Soil and Reduced the Risk of Secondary Pollution Through Promotion of Plant Growth, Degradation of DEHP in Soil and Modulation of Rhizosphere Bacterial Community. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-W.; Guan, D.-X.; Qiu, L.-X.; Luo, Y.; Liu, F.; Teng, H.H.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Ma, L.Q. Spatial Dynamics of Phosphorus Mobilization by Mycorrhiza. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 206, 109797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Gu, C.; Xiao, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Microbial Inoculations Promoted the Rice Plant Growth by Regulating the Root-Zone Bacterial Community Composition and Potential Function. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2023, 23, 5222–5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, M.S.; Shahzadi, F.; Ali, F.; Shakeela, Q.; Niaz, Z.; Ahmed, S. Comparative Effect of Fertilization Practices on Soil Microbial Diversity and Activity: An Overview. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 3644–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Humphreys, E.; Tuong, T.P.; Barker, R. Rice and Water. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 92, pp. 187–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobermann, A.; Fairhurst, T. Rice: Nutrient Disorders & Nutrient Management; International Rice Research Institute: Los Baños, Philippines, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Shen, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tang, Y.; Allen, S.C. Controlled-Release Urea Reduced Nitrogen Leaching and Improved Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Yield of Direct-Seeded Rice. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 220, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Filho, M.P.B.; Moreira, A.; Guimarães, C.M. Foliar Fertilization of Crop Plants. J. Plant Nutr. 2009, 32, 1044–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jifon, J.L.; Lester, G.E. Foliar Potassium Fertilization Improves Fruit Quality of Field-Grown Muskmelon on Calcareous Soils in South Texas. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 2452–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.; Silberbush, M. Response of maize to foliar vs. soil application of nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium fertilizers. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünemann, E.K.; Bongiorno, G.; Bai, Z.; Creamer, R.E.; De Deyn, G.; de Goede, R.; Fleskens, L.; Geissen, V.; Kuyper, T.W.; Mäder, P.; et al. Soil Quality—A Critical Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Caspari, T.; Gonzalez, M.R.; Batjes, N.H.; Mäder, P.; Bünemann, E.K.; de Goede, R.; Brussaard, L.; Xu, M.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; et al. Effects of Agricultural Management Practices on Soil Quality: A Review of Long-Term Experiments for Europe and China. Agric. Ecosyst. 2018, 265, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trap, J.; Bonkowski, M.; Plassard, C.; Villenave, C.; Blanchart, E. Ecological Importance of Soil Bacterivores for Ecosystem Functions. Plant Soil 2016, 398, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.R.; Karlen, D.L.; Veum, K.S.; Moorman, T.B.; Cambardella, C.A. Biological Soil Health Indicators Respond to Tillage Intensity: A US Meta-Analysis. Geoderma 2020, 369, 114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Qin, S.; Sun, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, C.; Hu, H.; Liu, B. Long-Term Nitrogen Fertilization Alters Microbial Community Structure and Denitrifier Abundance in the Deep Vadose Zone. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 2394–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T/JAAASS 145-2024; Technical Code for Soil Health Assessment in Farmland. Jiangsu Society of Agricultural Science: Nanjing, China, 2024.

- Pansu, M.; Gautheyrou, J. (Eds.) pH Measurement. In Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 551–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansu, M.; Gautheyrou, J. (Eds.) Water Content and Loss on Ignition. In Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansu, M.; Gautheyrou, J. (Eds.) Organic and Total C, N (H, O, S) Analysis. In Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 327–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixen, P.E.; Grove, J.H. Testing Soils for Phosphorus. In Soil Testing and Plant Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 141–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haby, V.A.; Russelle, M.P.; Skogley, E.O. Testing Soils for Potassium, Calcium, and Magnesium. In Soil Testing and Plant Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 181–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sahoo, J.; Raza, M.B.; Barman, M.; Das, R. Ongoing Soil Potassium Depletion under Intensive Cropping in India and Probable Mitigation Strategies. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An Ultra-Fast Single-Node Solution for Large and Complex Metagenomics Assembly via Succinct de Bruijn Graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a Reference Resource for Gene and Protein Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D457–D462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Szklarczyk, D.; Heller, D.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Forslund, S.K.; Cook, H.; Mende, D.R.; Letunic, I.; Rattei, T.; Jensen, L.J.; et al. eggNOG 5.0: A Hierarchical, Functionally and Phylogenetically Annotated Orthology Resource Based on 5090 Organisms and 2502 Viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D309–D314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, Q.; Lin, L.; Cheng, L.; Deng, Y.; He, Z. NCycDB: A Curated Integrative Database for Fast and Accurate Metagenomic Profiling of Nitrogen Cycling Genes. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Tu, Q.; Yu, X.; Qian, L.; Wang, C.; Shu, L.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Huang, Z.; He, J.; et al. PCycDB: A Comprehensive and Accurate Database for Fast Analysis of Phosphorus Cycling Genes. Microbiome 2022, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment Using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- bwa-mem2. bwa-mem2/README.md at Master·bwa-mem2/bwa-mem2. GitHub. Available online: https://github.com/bwa-mem2/bwa-mem2/blob/master/README.md (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Woodcroft, B.J.; Singleton, C.M.; Boyd, J.A.; Evans, P.N.; Emerson, J.B.; Zayed, A.A.F.; Hoelzle, R.D.; Lamberton, T.O.; McCalley, C.K.; Hodgkins, S.B.; et al. Genome-Centric View of Carbon Processing in Thawing Permafrost. Nature 2018, 560, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, K.; Hosseini, S. Introduction to R Programming and RStudio Integrated Development Environment (IDE). In R Programming: Statistical Data Analysis in Research; Okoye, K., Hosseini, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolyniak, M.J.; Frazier, R.H.; Gemborys, P.K.; Loehr, H.E. Malate Dehydrogenase: A Story of Diverse Evolutionary Radiation. Essays Biochem. 2024, 68, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudijk, L.; Gaal, J.; de Krijger, R.R. The Role of Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Analysis of Succinate Dehydrogenase in the Diagnosis of Endocrine and Non-Endocrine Tumors and Related Syndromes. Endocr. Pathol. 2019, 30, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Cron, B.R.; Toner, B.M.; Anantharaman, K.; Breier, J.A.; Dick, G.J.; Li, M. Gammaproteobacteria Mediating Utilization of Methyl-, Sulfur- and Petroleum Organic Compounds in Deep Ocean Hydrothermal Plumes. ISME J. 2020, 14, 3136–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyksma, S.; Bischof, K.; Fuchs, B.M.; Hoffmann, K.; Meier, D.; Meyerdierks, A.; Pjevac, P.; Probandt, D.; Richter, M.; Stepanauskas, R.; et al. Ubiquitous Gammaproteobacteria Dominate Dark Carbon Fixation in Coastal Sediments. ISME J. 2016, 10, 1939–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Z.; Tripathi, G.D.; Mishra, M.; Dashora, K. Actinomycetes—The Microbial Machinery for the Organic-Cycling, Plant Growth, and Sustainable Soil Health. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 101893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, R.; Gopika, G.; Dhanasekaran, D.; Saravanamuthu, R. Isolation, Characterisation and Antifungal Activity of Marine Actinobacteria from Goa and Kerala, the West Coast of India. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2012, 45, 1010–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.B.; Rodrigues, A. Ecology of Thermophilic Fungi. In Fungi in Extreme Environments: Ecological Role and Biotechnological Significance; Tiquia-Arashiro, S.M., Grube, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garritano, A.N.; Song, W.; Thomas, T. Carbon Fixation Pathways across the Bacterial and Archaeal Tree of Life. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, I.A. Ecological Aspects of the Distribution of Different Autotrophic CO2 Fixation Pathways. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hügler, M.; Sievert, S.M. Beyond the Calvin Cycle: Autotrophic Carbon Fixation in the Ocean. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2011, 3, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daims, H.; Lebedeva, E.V.; Pjevac, P.; Han, P.; Herbold, C.; Albertsen, M.; Jehmlich, N.; Palatinszky, M.; Vierheilig, J.; Bulaev, A.; et al. Complete Nitrification by Nitrospira Bacteria. Nature 2015, 528, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Seven, J.; Zilla, T.; Dippold, M.A.; Kuzyakov, Y. Microbial Phosphorus Recycling in Soil by Intra- and Extracellular Mechanisms. ISME Commun. 2024, 3, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Liu, G.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Ai, S.; Wei, D.; Li, D.; Ma, B.; Tang, C.; et al. Long-Term Nutrient Inputs Shift Soil Microbial Functional Profiles of Phosphorus Cycling in Diverse Agroecosystems. ISME J. 2020, 14, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, J.; He, P.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Ma, M.; Ling, N. Microbial Phosphorus-Cycling Genes in Soil under Global Change. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Thomas, B.W.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Xu, W.; Chang, X.; Huang, R.; Wang, M.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y. Phosphorus Cycling Genes, Enzyme Activities and Microbial Communities Shift Based on Green Manure Residues and Soil Environment. Pedosphere 2025, S1002016025000657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Tang, F.; Wang, Y. Microbial Mechanisms for Improved Soil Phosphorus Mobilization in Monoculture Conifer Plantations by Mixing with Broadleaved Trees. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 120955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Bossio, D.A.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Rillig, M.C. The Concept and Future Prospects of Soil Health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H.; Abdollahi-Bastam, S.; Aghaee, A.; Ghorbanpour, M. Foliar-Applied Silicate Potassium Modulates Growth, Phytochemical, and Physiological Traits in Cichorium intybus L. under Salinity Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.C.Z.; Pereira, R.F.; da Silva Ferreira, R.; Alves, S.B.; de Sousa, F.S.; Rodrigues, S.S.; de Brito Neto, J.F.; de Melo, A.S.; da Silva, R.M.; de Mesquita, E.F. Silicon and Potassium Synergistically Alleviate Salt Stress and Enhance Soil Fertility, Nutrition, and Physiology of Passion Fruit Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1685221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mogy, M.; Abdeldaym, E.A.; Abdelaziz, S.M.; Ismail, A.M.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Ramadan, K.M.A.; Mahmoud, A.W.M.; Mottaleb, S.A. Foliar Application of Calcium, Silicon, and Potassium Nanoparticles Improves Growth, and Fruit Quality of Drought-Stressed Cucumber Plants through Modulation of Osmolytes, Antioxidant Enzymes, Photosynthesis Efficiency, and Phytohormones. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2025, 53, 14470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Yamaji, N. Silicon Uptake and Accumulation in Higher Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, W.T. Potassium Influences on Yield and Quality Production for Maize, Wheat, Soybean and Cotton. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Nahar, K.; Hossain, M.S.; Mahmud, J.A.; Hossen, M.S.; Masud, A.A.C.; Moumita; Fujita, M. Potassium: A Vital Regulator of Plant Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses. Agron. J. 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Nguyen, C.; Finlay, R.D. Carbon Flow in the Rhizosphere: Carbon Trading at the Soil–Root Interface. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haichar, F.E.Z.; Santaella, C.; Heulin, T.; Achouak, W. Root Exudates Mediated Interactions Belowground. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Dumont, M.G.; Di, H.; Xu, J.; et al. Atmospheric Methane Oxidation Is Affected by Grassland Type and Grazing and Negatively Correlated to Total Soil Respiration in Arid and Semiarid Grasslands in Inner Mongolia. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Li, J.; Liao, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Zhao, J. Linking Microbial Metabolism and Ecological Strategies to Soil Carbon Cycle Function in Agroecosystems. Soil Till. Res. 2025, 251, 106562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolton, M.; Sela, N.; Elad, Y.; Cytryn, E. Comparative Genomic Analysis Indicates That Niche Adaptation of Terrestrial Flavobacteria Is Strongly Linked to Plant Glycan Metabolism. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Carrión, V.J. Importance of Bacteroidetes in Host–Microbe Interactions and Ecosystem Functioning. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujakić, I.; Piwosz, K.; Koblížek, M. Phylum Gemmatimonadota and Its Role in the Environment. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, P.E.; Knobbe, L.N.; Chanton, P.; Zaugg, J.; Mortazavi, B.; Mason, O.U. Uncovering Novel Functions of the Enigmatic, Abundant, and Active Anaerolineae in a Salt Marsh Ecosystem. mSystems 2024, 10, e01162-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.C.; Grand, S.; Verrecchia, É.P. Calcium-Mediated Stabilisation of Soil Organic Carbo. Biogeochemistry 2018, 137, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Yang, F.; Sun, Z.; Miao, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G. Asymmetric Responses of Soil Organic Carbon Stability to Shifting Dominance of pH-Mediated Metal-Bound Organic Carbon. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hassan, M.; Bo, X.; Guo, L. Fumarate-Based Metal-Organic Framework/Mesoporous Carbon as a Novel Electrochemical Sensor for the Detection of Gallic Acid and Luteolin. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 849, 113378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Tang, C.; Li, Y.; Guggenberger, G.; Xu, J. Succession of the Soil Bacterial Community as Resource Utilization Shifts from Plant Residues to Rhizodeposits. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 108785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Myrold, D.; Tiedje, J. Soil Organic Carbon in a Changing World. Pedosphere 2017, 27, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Van Zwieten, L.; Liang, C.; Xu, J.; Guggenberger, G.; Luo, Y. Deciphering the Microbial Players Driving Straw Decomposition and Accumulation in Soil Components of Particulate and Mineral-Associated Organic Matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 209, 109871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, S.; Parfrey, L.W.; Doebeli, M. Decoupling Function and Taxonomy in the Global Ocean Microbiome. Science 2016, 353, 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, M.G.; Stein, L.Y. Nitrifier Genomics and Evolution of the Nitrogen Cycle. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 278, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The Microbial Nitrogen-Cycling Network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Pan, W.; Tang, S.; Sun, X.; Xie, Y.; Chadwick, D.R.; Hill, P.W.; Si, L.; Wu, L.; Jones, D.L. Maize and Soybean Experience Fierce Competition from Soil Microorganisms for the Uptake of Organic and Inorganic Nitrogen and Sulphur: A Pot Test Using 13C, 15N, 14C, and 35S Labelling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 157, 108260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Tang, C.; Xu, J. Labile and Recalcitrant Carbon Inputs Differ in Their Effects on Microbial Phosphorus Transformation in a Flooded Paddy Soil with Rice (Oryza Sativa L.). Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 198, 105372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Anđelković, S.; Panneerselvam, P.; Senapati, A.; Vasić, T.; Ganeshamurthy, A.N.; Chauhan, M.; Uniyal, N.; Mahakur, B.; Radha, T.K. Phosphate-Solubilizing Microbes and Biocontrol Agent for Plant Nutrition and Protection: Current Perspective. Commun. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2020, 51, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. Belowground Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; van Straalen, N.M. The Unseen Majority: Soil Microbes as Drivers of Plant Diversity and Productivity in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamani, M.M.; Hughes, A.C.; Qureshi, S.; Zhang, Q.; Tarafder, E.; Das, D.; Acharya, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.-G. Microbial Biodiversity and Plant Functional Trait Interactions in Multifunctional Ecosystems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 201, 105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini-Andreote, F.; van Elsas, J.D. Back to the Basics: The Need for Ecophysiological Insights to Enhance Our Understanding of Microbial Behaviour in the Rhizosphere. Plant Soil 2013, 373, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, Q.; Xie, H.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, L.; Liu, Y.; Ding, F.; Zhao, C.; et al. Foliar Fertilization-Induced Rhizosphere Microbial Mechanisms for Soil Health Enhancement. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122837

Zeng Q, Xie H, Zheng S, Zhao Y, Zhang X, Zheng Y, Lu L, Liu Y, Ding F, Zhao C, et al. Foliar Fertilization-Induced Rhizosphere Microbial Mechanisms for Soil Health Enhancement. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122837

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Qinwen, Hua Xie, Siyuan Zheng, Yuzhuo Zhao, Xiaoyue Zhang, Yunyou Zheng, Luotian Lu, Yonghong Liu, Fenghua Ding, Chengsen Zhao, and et al. 2025. "Foliar Fertilization-Induced Rhizosphere Microbial Mechanisms for Soil Health Enhancement" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122837

APA StyleZeng, Q., Xie, H., Zheng, S., Zhao, Y., Zhang, X., Zheng, Y., Lu, L., Liu, Y., Ding, F., Zhao, C., Song, X., & Ma, B. (2025). Foliar Fertilization-Induced Rhizosphere Microbial Mechanisms for Soil Health Enhancement. Agronomy, 15(12), 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122837