Phosphorus Input Threshold Drives the Synergistic Shift of Microbial Assembly and Phosphorus Speciation to Sustain Maize Productivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Design

2.2. Soil Sampling and Analysis

2.3. Plant Sample Collection and Determination

2.4. Analysis of Soil Phosphorus Fractions

2.5. DNA Extraction, Illumina NovaSeq Sequencing, and Data Processing

2.6. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis of Bacteria and Fungi

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Phosphorus Application Modulates Soil Chemistry and Microbial Biomass in Purple Soil

3.2. Response of Soil Phosphorus Fractions to Phosphorus Application

3.3. Alpha/Beta-Diversity and Community Structure of Bacterial and Fungal Communities

3.4. Effects of Phosphorus Application on Soil Microbial Network Complexity

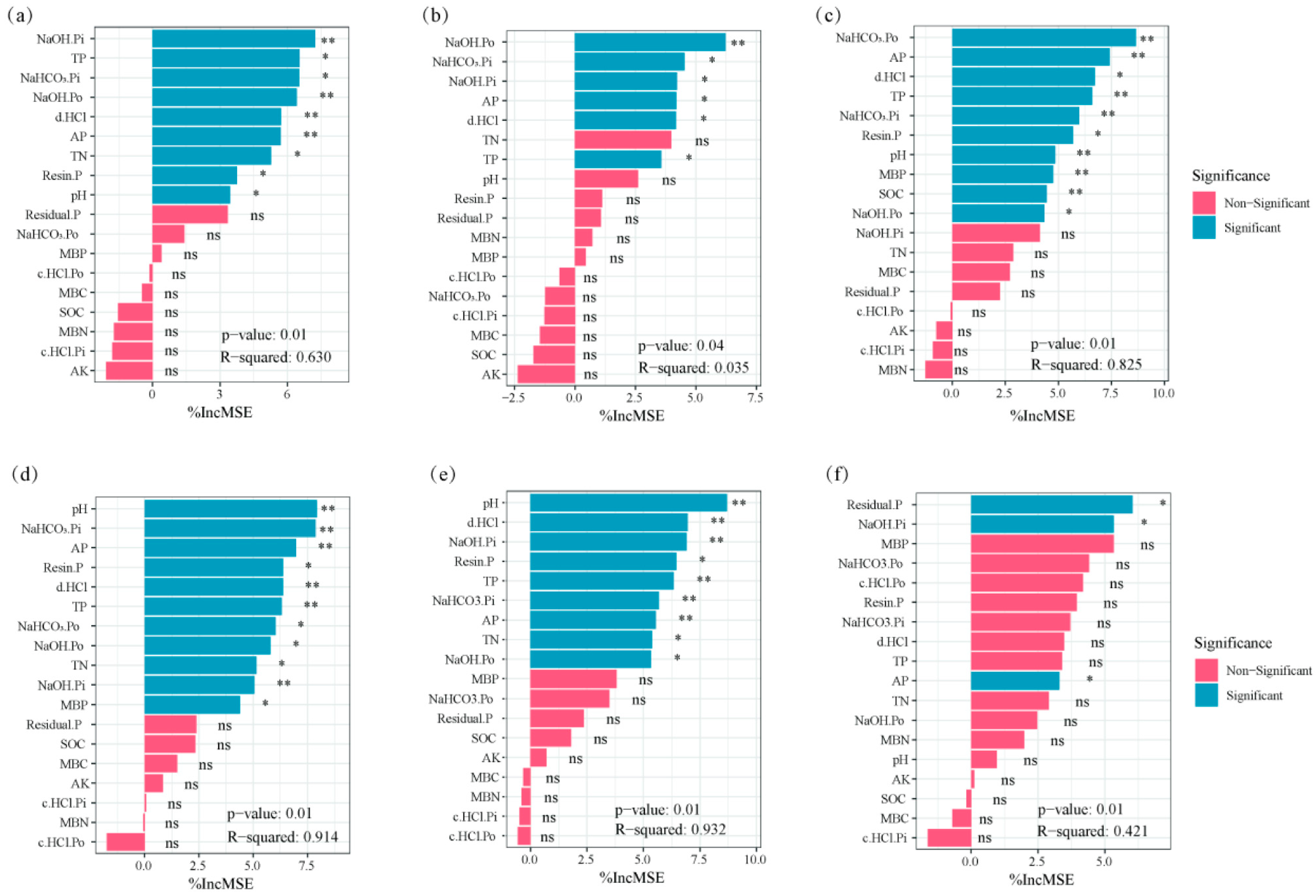

3.5. Correlation Between Soil Chemical Properties and Microbial Communities

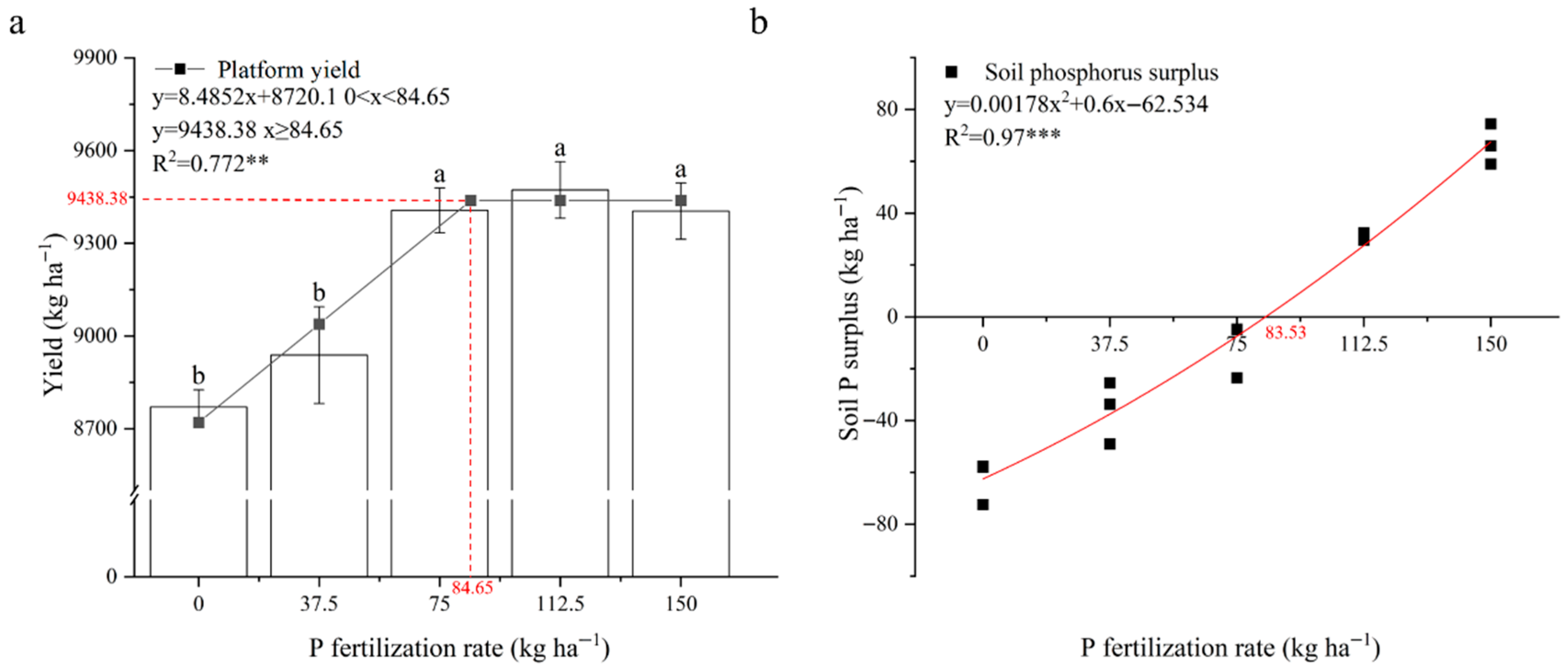

3.6. Regulatory Mechanisms of Phosphorus Application Rate on Maize Yield Formation, Root Architecture, and Phosphorus Utilization Efficiency

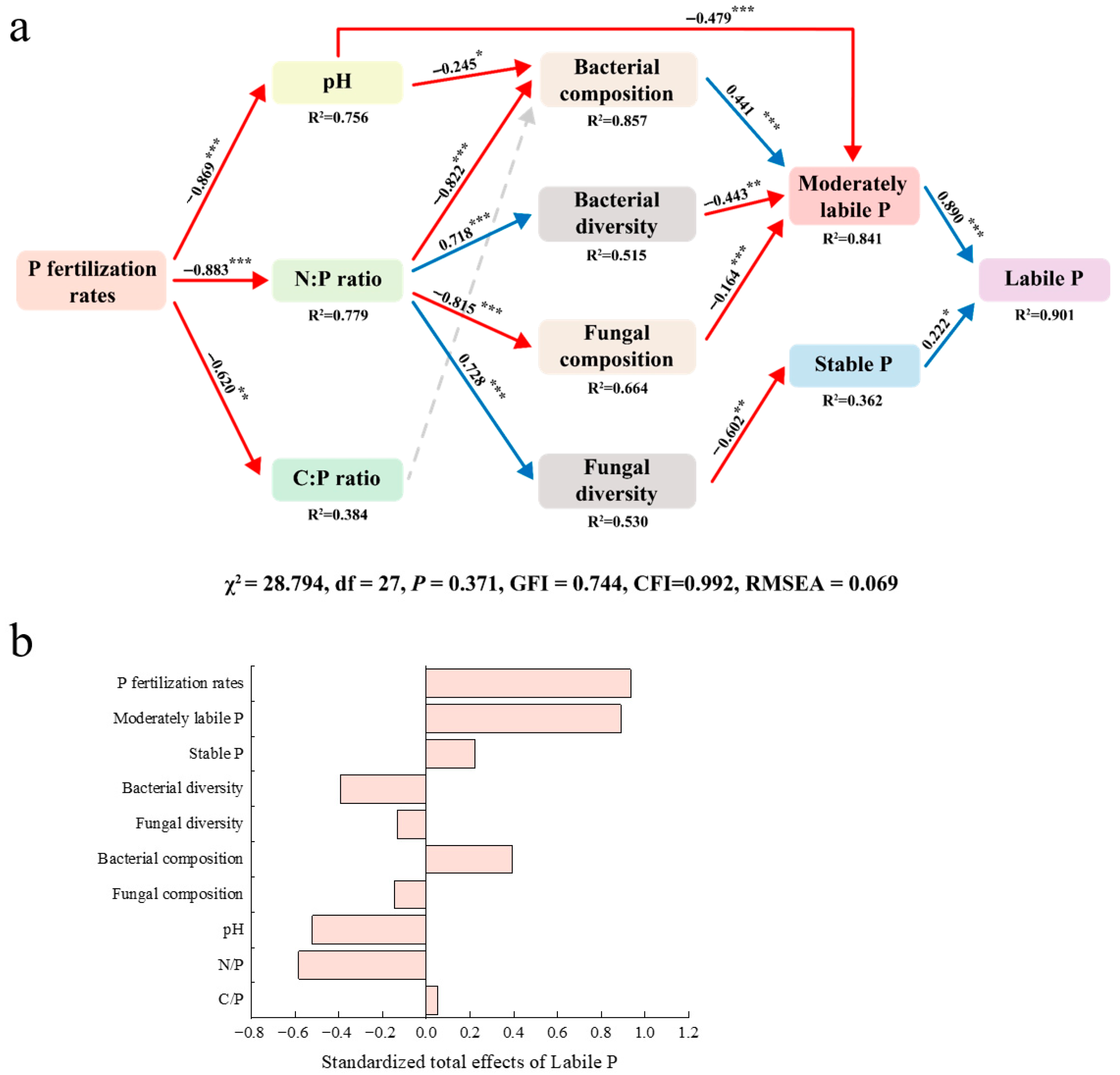

3.7. Mechanisms of Phosphorus Component Effects on Corn Yield and Phosphorus Utilization Efficiency

4. Discussion

4.1. Regulatory Mechanisms of Phosphorus Fertilization on Chemical Properties and Phosphorus Speciation Transformation in Purple Soil

4.2. Regulatory Mechanisms of Phosphorus Fertilization on Microbial Community Structure and Function in Purple Soil

4.3. Synergistic Regulatory Mechanisms of Phosphorus Application Rates on Maize Yield Formation and Phosphorus Use Efficiency

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P | Phosphorus |

| LP | Labile phosphorus |

| MP | Moderately labile phosphorus |

| SP | Stable phosphorus |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| MBN | Microbial biomass nitrogen |

| MBC | Microbial biomass carbon |

| MBP | Microbial biomass phosphorus |

References

- Ducousso-Détrez, A.; Fontaine, J.; Sahraoui, A.L.; Hijri, M. Diversity of phosphate chemical forms in soils and their contribu-tions on soil microbial community structure changes. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.; Tian, Y.; Ma, Q.; Ahmed, W.; Mehmood, S.; Hui, X.; Wang, Z. Changes in phosphorus fractions and its availability status in relation to long term P fertilization in loess plateau of China. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demay, J.; Ringeval, B.; Pellerin, S.; Nesme, T. Half of global agricultural soil phosphorus fertility derived from anthropogenic sources. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alewell, C.; Ringeval, B.; Ballabio, C.; Robinson, D.A.; Panagos, P.; Borrelli, P. Global phosphorus shortage will be aggravated by soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A. Global trends of cropland phosphorus use and sustainability challenges. Nature 2022, 611, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Feng, G. Dynamics between soil fixation of fertilizer phosphorus and biological phosphorus mobilization determine the phosphorus budgets in agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 375, 109174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Alewell, C.; Borrelli, P.; Panagos, P.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, F.; Yang, S.; Sui, Y.; et al. Pervasive soil phosphorus losses in terrestrial ecosystems in China. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Q.; Zheng, Z.M.; Drury, C.F.; Hu, Q.C.; Tan, C.S. Legacy phosphorus after 45 years with consistent cropping systems and fertilization compared to native soils. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zheng, X.; Wei, X.; Kai, Z.; Xu, Y. Excessive application of chemical fertilizer and organophosphorus pesticides induced total phosphorus loss from planting causing surface water eutrophication. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Tian, L.; Wei, X. Long-term straw return promotes soil phosphorus cycling by enhancing soil microbial functional genes responsible for phosphorus mobilization in the rice rhizosphere. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 381, 109422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Yin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z. A dynamic optimization of soil phosphorus status approach could reduce phosphorus fertilizer use by half in China. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Xiang, Y.; Jin, M.; Chen, C. Global patterns and drivers of phosphorus fraction variability in cropland soils. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 223, 108498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermoere, S.; Sande, T.V.D.; Tavernier, G.; Lauwers, L.; Goovaerts, E.; Sleutel, S.; Neve, S.D. Soil phosphorus (P) mining in agriculture—Impacts on P availability, crop yields and soil organic carbon stocks. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, A.; Yu, G.; Mao, Q.; Zheng, M.; Huang, J.; Tan, X.; Mo, J.; et al. Adsorption/desorption processes dominate the soil P fractions dynamic under long-term N/P addition in a subtropical forest. Geoderma 2025, 457, 117284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, M.; Cai, Y.; Weng, X.; Su, D.; Guo, J.; Wang, W.; Hou, Y.; Ye, D.; et al. Long-term excessive phosphorus fertilization alters soil phosphorus fractions in the acidic soil of pomelo orchards. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yuan, J.; Wang, S.; Liang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y. Soil and microbial C:N:P stoichiometries play vital roles in regulating P transformation in agricultural ecosystems: A review. Pedosphere 2024, 34, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biassoni, M.M.; Vivas, H.; Gutiérrez-Boem, F.H.; Salvagiotti, F. Changes in soil phosphorus (P) fractions and P bioavailability after 10 years of continuous P fertilization. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 232, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Hagedorn, F.; Penuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Tan, X.; Yan, Z.; He, C.; Ni, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, J.; et al. Differential responses of soil phosphorus fractions to nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization: A global meta-analysis. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2024, 38, e2023GB008064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.F.; Gao, M.; Xie, D.T.; Wang, Z.F.; Chen, C. Inorganic phosphorus in a regosol (purple) soil under long-term phosphorus fertilization. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2016, 25, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Xu, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, A.; Duan, C.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Land use effects on soil phosphorus behavior characteristics in the eutrophic aquatic-terrestrial ecotone of Dianchi lake, China. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Zou, W.; Chen, X.; Zou, C.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, F.; Yu, P.; Chen, X. Soil microbial composition and phoD gene abundance are sensitive to phosphorus level in a long-term wheat-maize crop system. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 605955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, R.; Liu, Q.; Qiang, W.; Liang, J.; Hou, E.; Zhao, C.; Pang, X. Linking soil phosphorus fractions to abiotic factors and the microbial community during subalpine secondary succession: Implications for soil phosphorus availability. Catena 2023, 233, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Guo, X.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, H. Biodiversity of key-stone phylotypes determines crop production in a 4-decade fertilization experiment. ISME J. 2021, 15, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Jia, P.; Feng, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Ou, S.; Wu, Z.; Liao, B.; Shu, W.; Liang, J.; et al. Remarkable effects of microbial factors onsoil phosphorus bio availability: A country-scale study. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4459–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Mahmood, M.; Jiao, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Long-term high-P fertilizer input shifts soil P cycle genes and microorganism communities in dryland wheat production systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Lalande, R.; Ziadi, N.; Sheng, M.; Hu, Z. An assessment of the soil microbial status after 17 years of tillage and mineral P fertilization management. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 62, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, H.; Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Lang, M.; Chen, X. Long-term moderate fertilization increases the complexity of soil microbial community and promotes regulation of phosphorus cycling genes to improve the availability of phosphorus in acid soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 194, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Han, X.; Hu, N.; Han, S.; Yuan, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Rengel, Z.; et al. The crop mined phosphorus nutrition via modifying root traits and rhizosphere micro-food web to meet the increased growth demand under elevated CO2. iMeta 2024, 3, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Xu, K.W.; Liu, W.G.; Zhang, C.C.; Chen, Y.X.; Yang, W.Y. More aboveground biomass, phosphorus accumulation and remobilization contributed to high productivity of intercropping wheat. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2017, 11, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Han, Z.; Du, J.; Ci, E.; Ni, J.; Xie, D.; Wei, C. Relationships between the lithology of purple rocks and the pedogenesis of purple soils in the Sichuan Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, D.; Sims, J.T. Recommended soil pH and lime requirement test. In Recommended Soil Testing Procedures for the Northeastern United States; Smims, J.T., Wolf, A., Eds.; Northeastern Regional Publication: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 493, pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Methods Soil Analysis Part 3: Chemical Methods; ACSESS: London, UK, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, L.E.; Nelson, D.W. Determination of total phosphorus in soils: A rapid perchloric acid digestion procedure. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1972, 36, 902–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.B.; Self, J.R.; Soltanpour, P.N. Optimal conditions for phosphorus analysis by the ascorbic acid-molybdenum blue method. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1994, 58, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agricultural Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.K. Analytic Methods for Soil Agricultural Chemistry; China Agriculture Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tiessen, H.; Moir, J.O. Characterization of Available P by Sequential Extraction; Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis 824; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, M.J.; O’Sullivan, O.; Wang, Q.; Nikkilä, J.; Marchesi, J.R.; Smidt, H.; Vos, W.M.D.; Ross, R.P.; O’Toole, P.W. Comparative analysis of pyrosequencing and a phylogenetic microarray for exploring microbial community structures in the human distal intestine. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, S.; Tang, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, P.; Zhang, Y. Novel insights into the rhizosphere and seawater microbiome of Zostera marina in diverse mariculture zones. Microbiome 2024, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y. Discovering the false discovery rate. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2010, 72, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009; Volume 3, pp. 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Arbizu, P. Pairwiseadonis: Pairwise Multilevel Comparison Using Adonis, R package version 0.4. 2020.

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Xia, Q.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Z. Rhizosphere soil properties, microbial community, and enzyme activities: Short-term responses to partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaeb, Z.A.; Summers, J.K.; Pugesek, B.H. Using structural equation modeling to investigate relationships among ecological variables. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2009, 7, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.B. Structural Equation Modeling and Natural Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachenik, D.; Fidel, J. Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2012, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, W.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, X.; Ren, F.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, B. Different responses of priming effects in long-term nitrogen- and phosphorus-fertilized soils to exogenous carbon inputs. Plant Soil 2024, 500, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cen, B.; Yu, Z.; Qiu, R.; Gao, T.; Long, X. The key role of biochar in amending acidic soil: Reducing soil acidity and improving soil acid buffering capacity. Biochar 2025, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Lambers, H.; Zhang, F. Changes in soil phosphorus fractions following sole cropped and intercropped maize and faba bean grown on calcareous soil. Plant Soil 2020, 448, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Müller, T.; Lakshmanan, P.; Liu, Y.; Liang, T.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, X. Soil phosphorus availability and fractionation in response to different phosphorus sources in alkaline and acid soils: A short-term incubation study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Sun, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, T.; Shakouri, M.; Zheng, L.; Sui, P.; et al. Iron-Tuned Depth-Dependent P Transformation on Calcium Carbonate Coprecipitates: The Impact of Fe and P Loadings. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15151–15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili-Rad, R.; Hosseini, H.M. Assessing the effect of phosphorus fertilizer levels on soil phosphorus fractionation in rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soils of wheat. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2017, 48, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, S.; Qiang, R.; Lu, E.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Q. Response of soil microbial community structure to phosphate fertilizer reduction and combinations of microbial fertilizer. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 899727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, F.; Li, Q.; Solanki, M.K.; Wang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Dong, D. Soil phosphorus transformation and plant uptake driven by phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1383813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Chenu, C.; Kappler, A.; Rillig, M.C.; Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, G.; Lin, Y.; Luo, J.; Di, H.J.; Lindsey, S.; Liu, D.; Fan, J.; Ding, W. Responses of soil fungal diversity and community composition to long-term fertilization: Field experiment in an acidic Ultisol and literature synthesis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 145, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Meng, Z.; Xua, R.; Duoji, D.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; et al. Soil microbial network complexity predicts ecosystem function along elevation gradients on the Tibetan Plateau. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 108766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Yang, T.; Bao, Y.; He, P.; Yang, K.; Mei, X.; Wei, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Banerjee, S. Network analysis and subsequent culturing reveal keystone taxa involved in microbial litter decomposition dynamics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 157, 108230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, B.; Ma, M.; Guan, D.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Cao, F.; Shen, D.; et al. Thirty four years of nitrogen fertilization decreases fungal diversity and alters fungal community composition in black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 95, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.J.; David, A.S.; Menges, E.S.; Searcy, C.A.; Afkhami, M.E. Environmental stress destabilizes microbial networks. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Cao, D.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Wei, L.; Guo, B.; Wang, S.; Ding, J.; Chen, H.; et al. Microbial carbon and phosphorus metabolism regulated by C:N:P stoichiometry stimulates organic carbon accumulation in agricultural soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 242, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Qu, Q.; Li, G.; Liu, G.; Geissen, V.; Ritsema, C.J.; Xue, S. Impact of nitrogen addition on plant-soil-enzyme C–N–P stoichiometry and microbial nutrient limitation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 170, 108714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ye, H.; Zhang, D.; Gu, J.; Deng, O. The dynamics of phosphorus fractions and the factors driving phosphorus cycle in Zoige Plateau peatland soil. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, N.; Borkar, S.; Garg, S. Phosphate solubilization by microorganisms: Overview, mechanisms, applications and advances. Adv. Biol. Sci. Res. 2019, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Deng, X.; Thomashow, L.S.; Lidbury, L.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Phosphorus availability influences disease-suppressive soil microbiome through plant-microbe interactions. Microbiome 2024, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Bai, H.; Dong, W.; Qiao, L.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine modifications stabilize phosphate starvation response–related mRNAs in plant adaptation to nutrient-deficient stress. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Chen, A.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Complex regulation of plant phosphate transporters and the gap between molecular mechanisms and practical application: What is missing? Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Rengel, Z.; Cheng, L.; Shen, J. Coupling phosphate type and placement promotes maize growth and phosphorus uptake by altering root properties and rhizosphere processes. Field Crop Res. 2024, 306, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gao, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Phosphorus fertilizer input threshold shifts bacterial community structure and soil multifunctionality to maintain dryland wheat production. Soil Till. Res. 2024, 243, 106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, B.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Xu, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; et al. Optimized phosphorus partitioning enhances phosphorus use efficiency in strip-intercropped soybean. Eur. J. Agron. 2026, 172, 127854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | pH | SOC | AP | TN | TP | AK | MBC | MBN | MBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | (g kg−1) | (g kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | ||

| P0 | 6.53 ± 0.03 a | 16.30 ± 2.14 b | 11.91 ± 0.61 d | 0.98 ± 0.02 b | 0.63 ± 0.01 d | 119.4 ± 4.96 a | 114.59 ± 4.97 ab | 17.61 ± 0.74 ab | 6.37 ± 1.41 b |

| P37.5 | 6.47 ± 0.03 a | 17.09 ± 1.27 b | 25.20 ± 1.86 c | 1.09 ± 0.01 b | 0.86 ± 0.08 c | 114.4 ± 12.33 a | 126.38 ± 2.19 ab | 17.03 ± 0.87 ab | 10.78 ± 2.63 b |

| P75 | 6.30 ± 0.00 b | 19.01 ± 1.33 b | 48.24 ± 2.32 b | 1.19 ± 0.02 ab | 1.20 ± 0.02 b | 114.5 ± 7.52 a | 127.04 ± 4.65 a | 15.86 ± 1.35 b | 14.46 ± 1.76 b |

| P112.5 | 6.17 ± 0.03 c | 21.10 ± 1.31 ab | 57.31 ± 0.26 a | 1.25 ± 0.04 a | 1.33 ± 0.01 a | 135.9 ± 10.10 a | 138.42 ± 16.58 a | 16.74 ± 0.80 ab | 27.12 ± 3.84 a |

| P150 | 6.20 ± 0.06 bc | 24.59 ± 0.67 a | 62.11 ± 2.11 a | 1.28 ± 0.07 a | 1.37 ± 0.02 a | 124.4 ± 2.93 a | 135.96 ± 6.10 a | 19.48 ± 0.73 a | 25.79 ± 7.27 a |

| C/N | N/P | C/P | MBC/MBN | MBN/MBP | MBC/MBP | ||||

| P0 | 16.72 ± 2.24 a | 1.55 ± 0.04 a | 25.78 ± 3.06 a | 6.55 ± 0.52 a | 3.02 ± 0.58 a | 19.45 ± 3.54 a | |||

| P37.5 | 15.65 ± 1.28 a | 1.29 ± 0.11 b | 20.43 ± 3.26 ab | 7.45 ± 0.24 a | 1.75 ± 0.38 b | 13.18 ± 3.10 ab | |||

| P75 | 15.98 ± 1.35 a | 0.99 ± 0.03 c | 15.79 ± 0.82 b | 8.15 ± 0.90 a | 1.15 ± 0.22 b | 9.04 ± 1.12 b | |||

| P112.5 | 16.82 ± 0.47 a | 0.94 ± 0.03 c | 15.84 ± 0.99 b | 8.24 ± 0.78 a | 0.66 ± 0.14 b | 5.51 ± 1.49 b | |||

| P150 | 19.35 ± 0.91 a | 0.93 ± 0.06 c | 17.98 ± 0.77 b | 7.02 ± 0.57 a | 0.97 ± 0.39 b | 6.40 ± 2.03 b | |||

| Treatments | Labile P | Moderately Labile P | Stable P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Proportion | Content | Proportion | Content | Proportion | |

| (mg kg−1) | (%) | (mg kg−1) | (%) | (mg kg−1) | (%) | |

| P0 | 96.32 ± 8.68 d | 15 a | 318.9 ± 9.34 d | 50 c | 215.1 ± 4.30 b | 34 a |

| P37.5 | 127.3 ± 14.69 c | 14 a | 493.4 ± 53.88 c | 57 b | 238.8 ± 22.97 ab | 27 b |

| P75 | 180.1 ± 3.21 b | 14 a | 780.5 ± 17.90 b | 64 a | 241.4 ± 3.44 ab | 20 c |

| P112.5 | 227.8 ± 1.56 a | 17 a | 853.7 ± 3.66 ab | 64 a | 250.6 ± 9.02 ab | 18 c |

| P150 | 223.2 ± 3.80 a | 16 a | 884.9 ± 22.39 a | 64 a | 261.2 ± 6.59 a | 19 c |

| Treatments | Ear Length (cm) | Ear Diameter (mm) | Bare Tip Length (cm) | Row Number per Spike | Kernels per Row | 1000-Grain Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | 15.69 ± 0.40 a | 47.79 ± 0.23 a | 15.49 ± 1.04 a | 14.37 ± 0.07 ab | 33.97 ± 2.12 a | 235.7 ± 4.1 b |

| P37.5 | 16.23 ± 0.35 a | 48.43 ± 0.46 a | 14.08 ± 0.78 ab | 14.50 ± 0.15 a | 35.32 ± 0.79 a | 234.6 ± 4.9 b |

| P75 | 15.94 ± 0.54 a | 48.32 ± 0.35 a | 12.96 ± 0.86 ab | 14.13 ± 0.09 ab | 34.80 ± 1.71 a | 256.4 ± 7.2 a |

| P112.5 | 16.32 ± 0.36 a | 47.51 ± 0.85 a | 12.33 ± 0.84 b | 13.97 ± 0.20 b | 35.57 ± 0.69 a | 256.7 ± 2.4 a |

| P150 | 15.84 ± 0.40 a | 48.65 ± 0.12 a | 12.89 ± 0.69 ab | 14.03 ± 0.15 b | 34.76 ± 1.52 a | 261.5 ± 7.3 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Zong, D.; Li, Y.; Penttinen, P.; Chen, X.; Kang, X.; Tang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gu, Y.; et al. Phosphorus Input Threshold Drives the Synergistic Shift of Microbial Assembly and Phosphorus Speciation to Sustain Maize Productivity. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122835

Wang J, Zong D, Li Y, Penttinen P, Chen X, Kang X, Tang X, Liu Y, Wu Y, Gu Y, et al. Phosphorus Input Threshold Drives the Synergistic Shift of Microbial Assembly and Phosphorus Speciation to Sustain Maize Productivity. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122835

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiangtao, Donglin Zong, Yongbo Li, Petri Penttinen, Xiaohui Chen, Xia Kang, Xiaoyan Tang, Yuanyuan Liu, Yingjie Wu, Yunfu Gu, and et al. 2025. "Phosphorus Input Threshold Drives the Synergistic Shift of Microbial Assembly and Phosphorus Speciation to Sustain Maize Productivity" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122835

APA StyleWang, J., Zong, D., Li, Y., Penttinen, P., Chen, X., Kang, X., Tang, X., Liu, Y., Wu, Y., Gu, Y., Xu, K., & Chen, Y. (2025). Phosphorus Input Threshold Drives the Synergistic Shift of Microbial Assembly and Phosphorus Speciation to Sustain Maize Productivity. Agronomy, 15(12), 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122835