Reconstructing Millennial-Scale Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Japan’s Cropland Cover

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

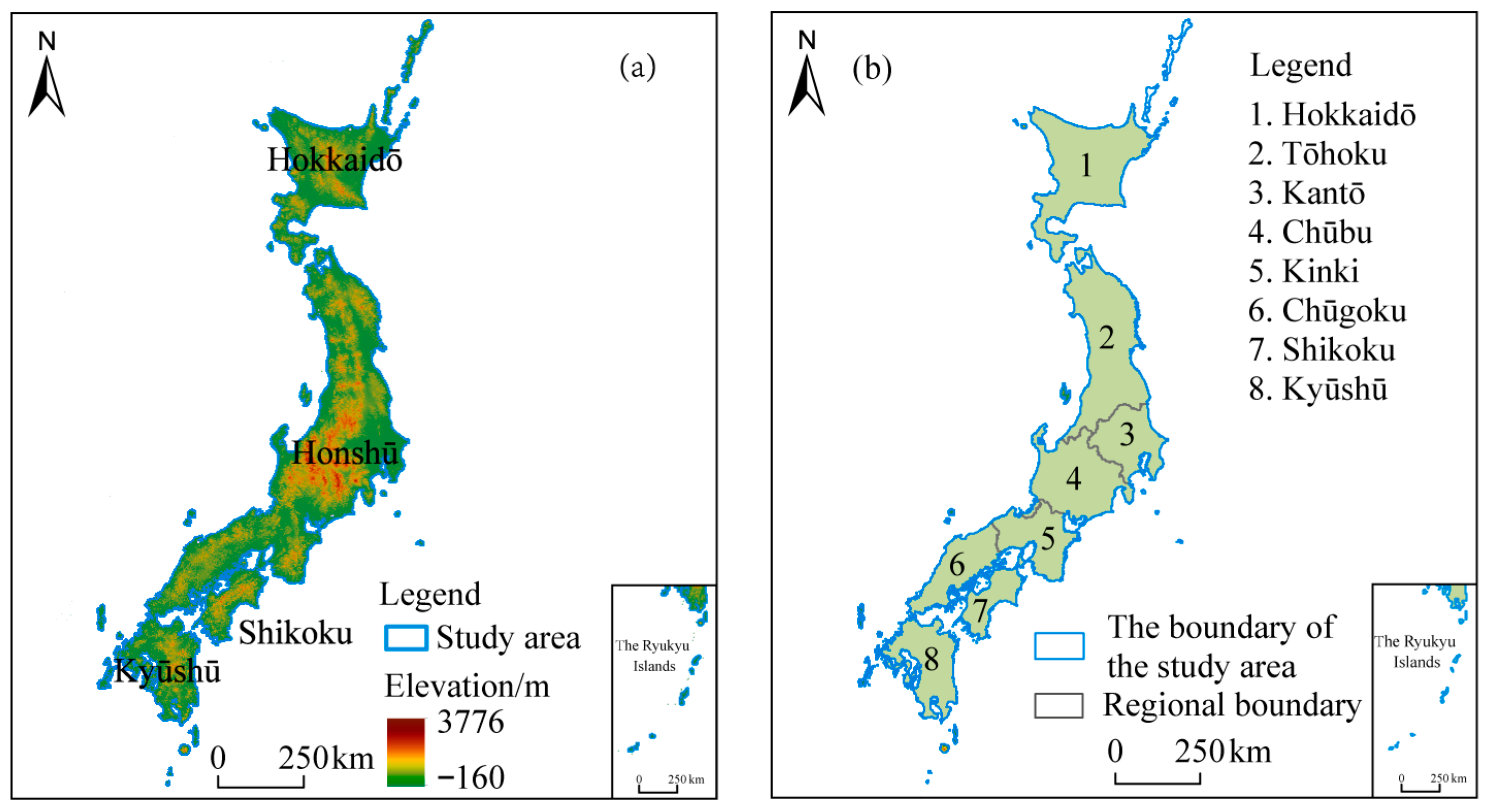

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Methods

2.2.1. Data Sources

Cropland Area Data

- (1)

- Fragmentary historical shōen records from the first year of Kyūan (1045 CE) to the second year of Tokuji (1307 CE) were sourced from the studies of Ono [41] and Takeuchi [42]. During the Heian to early Sengoku periods (800–1583 CE), shōen constituted the fundamental agricultural production units in Japan. Manor lords leased cropland (shōden) to farm households, collecting taxes based on the leased area [43]. The shōden figures recorded in historical documents likely registered by manor lords to secure tax revenue, suggesting reasonable reliability.

- (2)

- National kenchi data from the third year of Keichō (1598 CE) were derived from the studies of Miyagawa [44] and Kanzaki [45], while the fifteen year of Kyōhō (1730 CE) kenchi records were obtained from the Great Japan Tax Records (Dai-Nippon Sozei-shi) [46]. Kenchi surveys under the kokudaka system involved government-led assessments of cropland and standardized rice yields. Officials (bugyō) conducted on-site measurements, classifying paddy and upland fields into graded productivity tiers. Standardized rice output per unit area was calculated for each tier, then multiplied by the surveyed area to derive total yield estimates [45]. Notably, for the third year of Keichō (1598 CE), only the rice yield data have been preserved.

- (3)

- Since the Meiji era, cropland area data have included: survey records for the fifth year of Meiji (1872 CE) derived from Den-Tanbetsu compiled by the Meiji government [47]; archives data from the thirteen year of Meiji (1880 CE) to the thirty-third year of Meiji (AD 1900) sourced from the Ministry of Finance [48]; and statistical datasets from the thirty-seventh year of Meiji (1904 CE) to 2000 obtained from the Statistics Bureau of Japan (https://www.stat.go.jp/index.htm, accessed on 21 September 2024).

| Data Types | Temporal Coverage | Spatial Coverage | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical shōen data | 1045–1307 CE | Manor | Ono [41], Takeuchi [42] |

| Historical kenchi data | 1598 and 1730 CE | National | Miyagawa [44], Kanzaki [45]; Great Japan Tax Records [46] |

| Cropland survey data | 1872–1900 CE | County | Den-Tanbetsu [47], the Ministry of Finance [48] |

| Cropland statistical data | 1904–2000 CE | County | The Statistics Bureau of Japan (https://www.stat.go.jp/index.htm, accessed on 21 September 2024) |

| Historical revised population data | 800–1150 CE | National | Kito [49] |

| 1192–1603 CE | National | Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism [50] | |

| 1721–1868 CE | National | Minami [51] | |

| 1705–1872 CE | Ritsuryō province | Sekiya [52] | |

| 800–1872 CE | Sub-regional | Kito [49] | |

| Population statistical data | 1872–1920 CE | National | Sekiya [52] |

| 1920–2000 CE | National | The Statistics Bureau of Japan (https://www.stat.go.jp/index.htm, accessed on 21 September 2024) | |

| Modern Remote sensing-based data | 1982–2015 CE | 30 m × 30 m | Liu et al. [13], http://data.ess.tsinghua.edu.cn/, (accessed on 12 June 2025) |

| Topographic data | 1960–2000 CE | 90 m × 90 m | The United States Geological Survey (USGS) (http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/, accessed on 12 June 2025) |

| Climatic variables | 1960–1990 CE | 10 m × 10 m | The Global Agro-ecological Zones (GAEZ) (https://gaez.fao.org, accessed on 13 June 2025) |

| Soil texture data | 2010 CE | 250 m × 250 m | SoilGrids (www.soilgrids.org, accessed on 13 June 2025) |

Population Data

Other Basic Data Required for Cropland Gridding Allocation

2.2.2. Methods for Cropland Area Reconstruction

National Cropland Area Reconstruction

Regional Cropland Area Reconstruction

2.2.3. Methods for Spatially Explicit Allocation

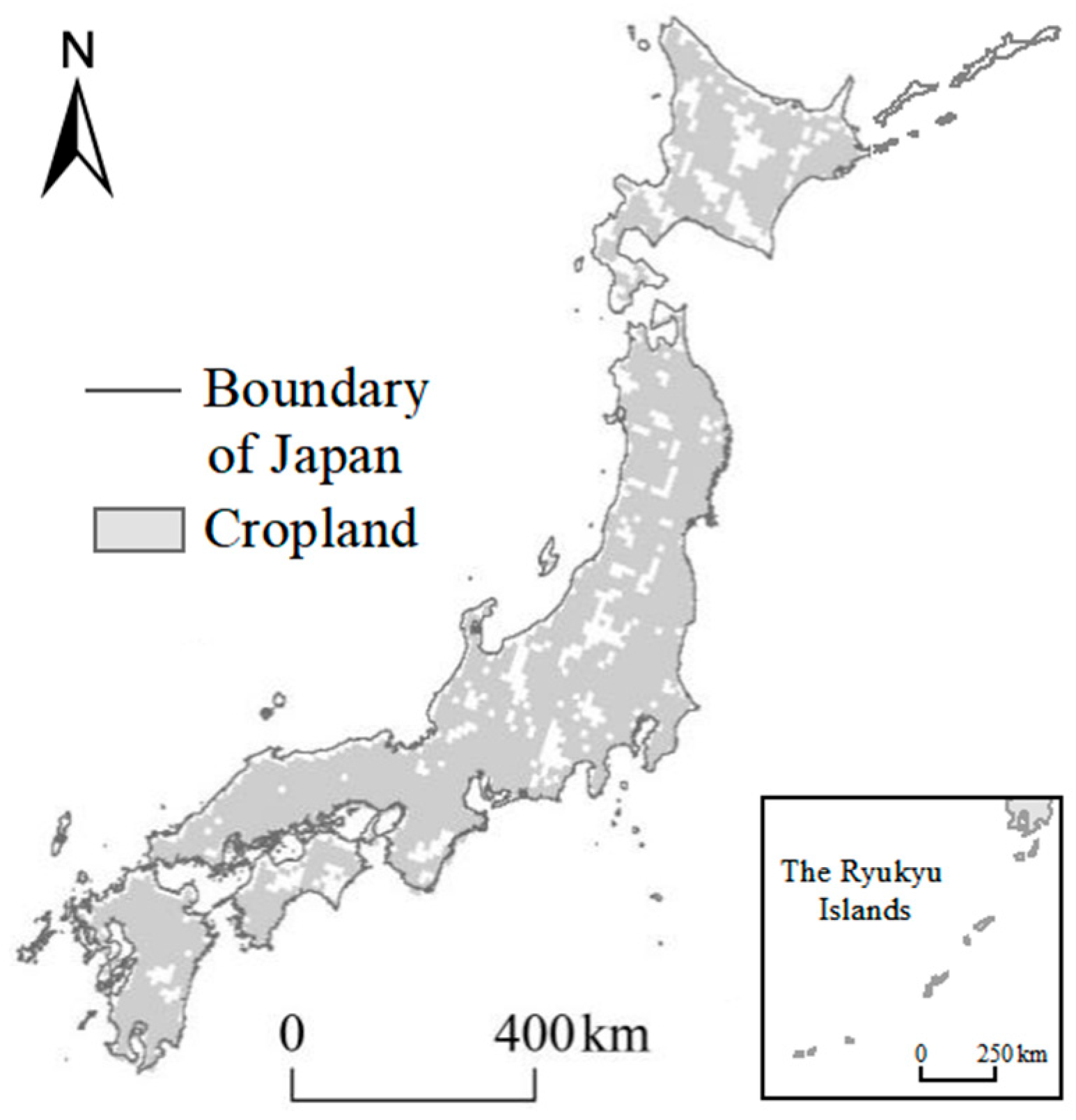

Determination of the Maximum Extent of Cropland

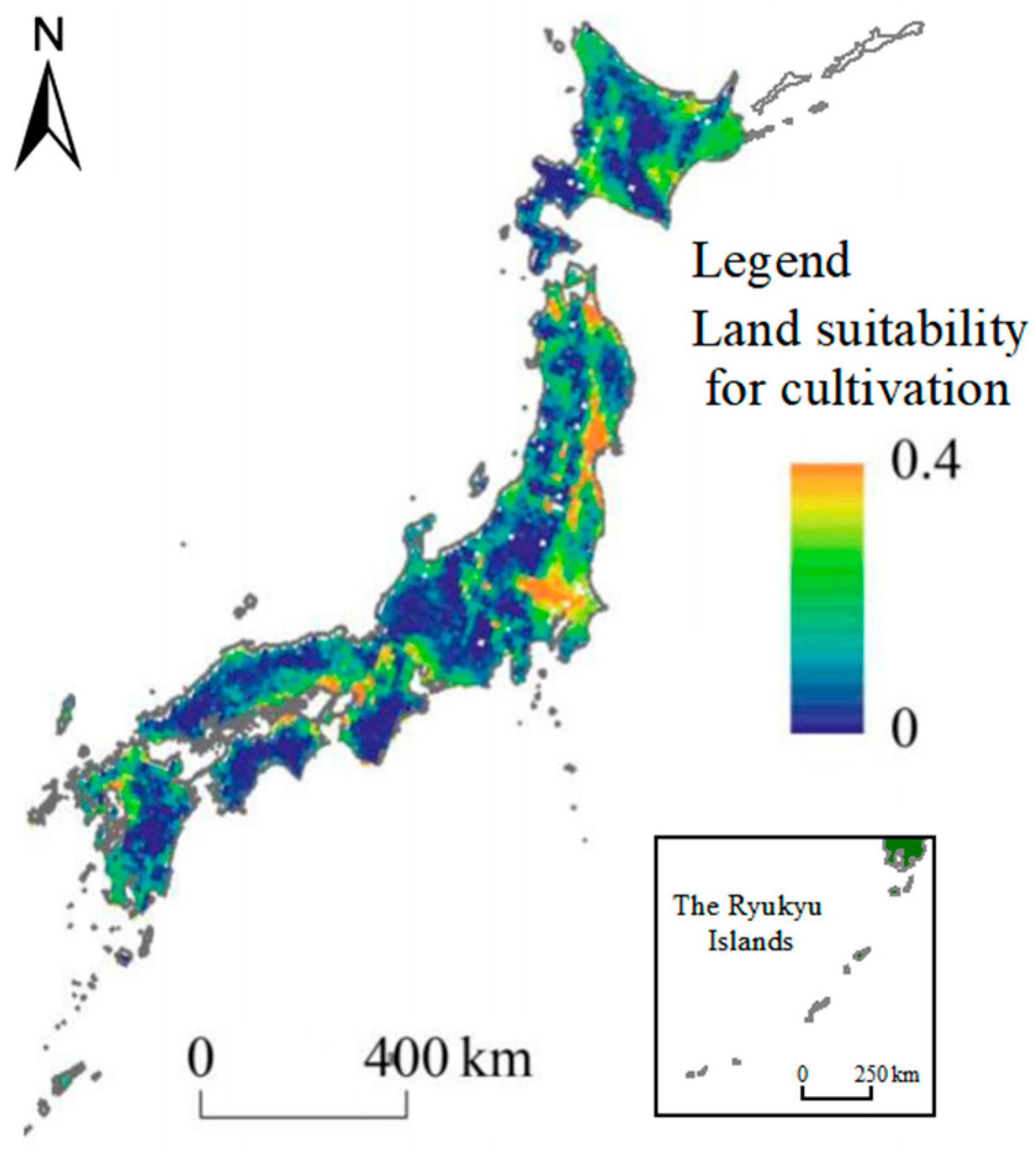

Land Suitability Model for Cultivation

- (1)

- The normalization equations for the elevation and slope factors are as follows:

- (2)

- The normalization of accumulated temperature and annual precipitation was performed using the following equations:

- (3)

- The soil texture factor was normalized using the following equation:

- (4)

- Land suitability for cultivation was computed as follows:

Gridding Allocation Method for Cropland

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Cropland Area over the Past Millennium

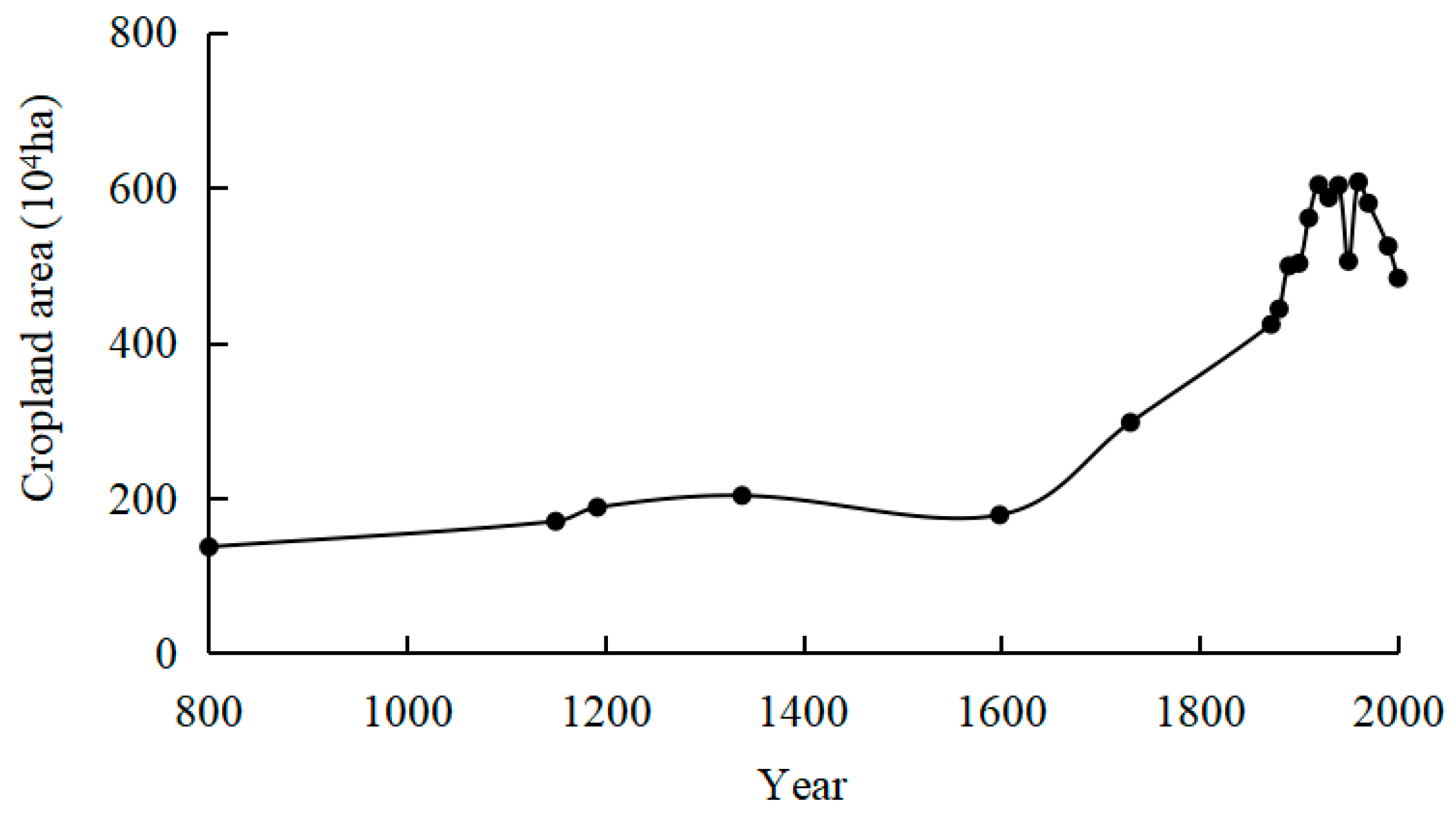

3.1.1. Changes at the National Level

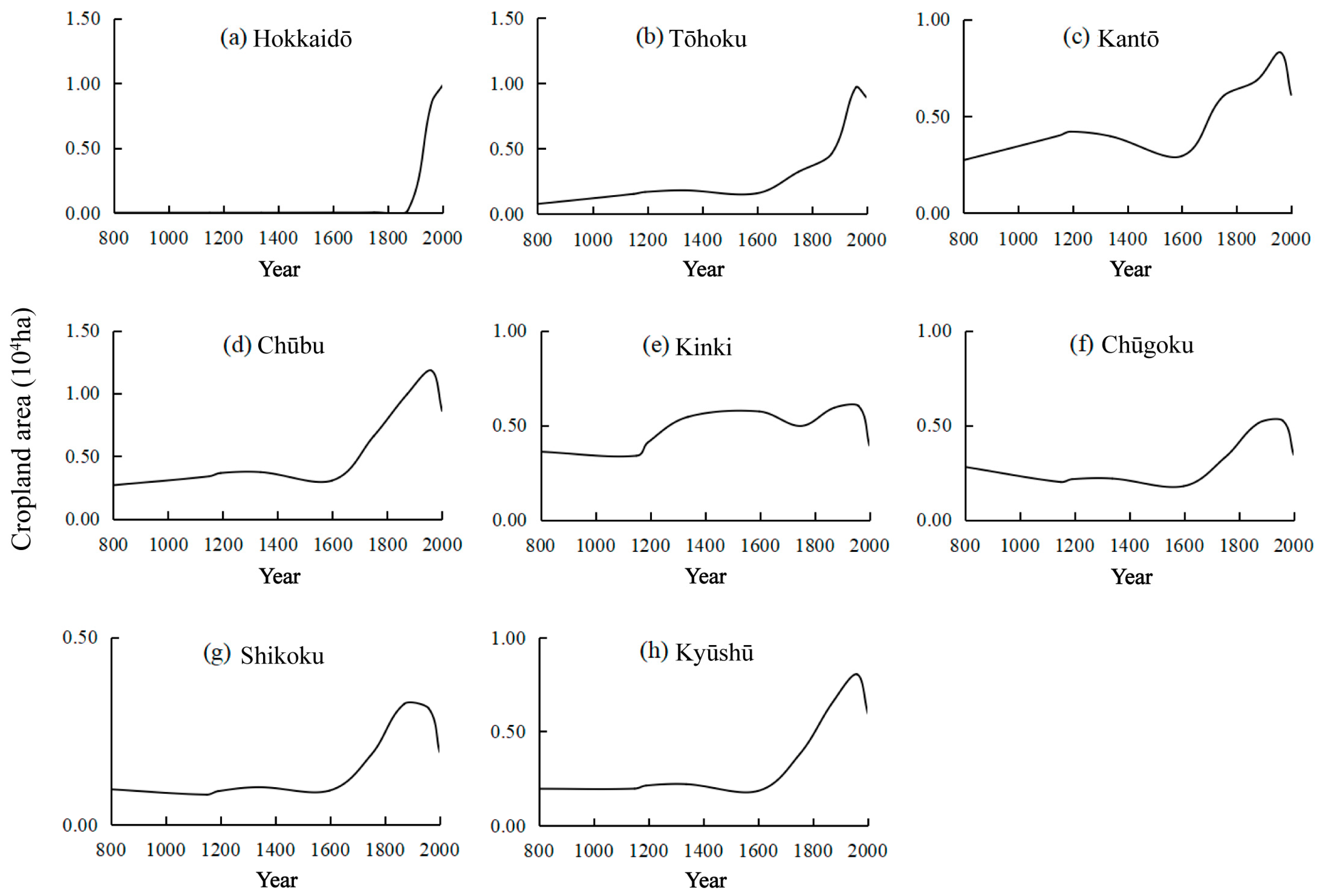

3.1.2. Changes at the Regional Level

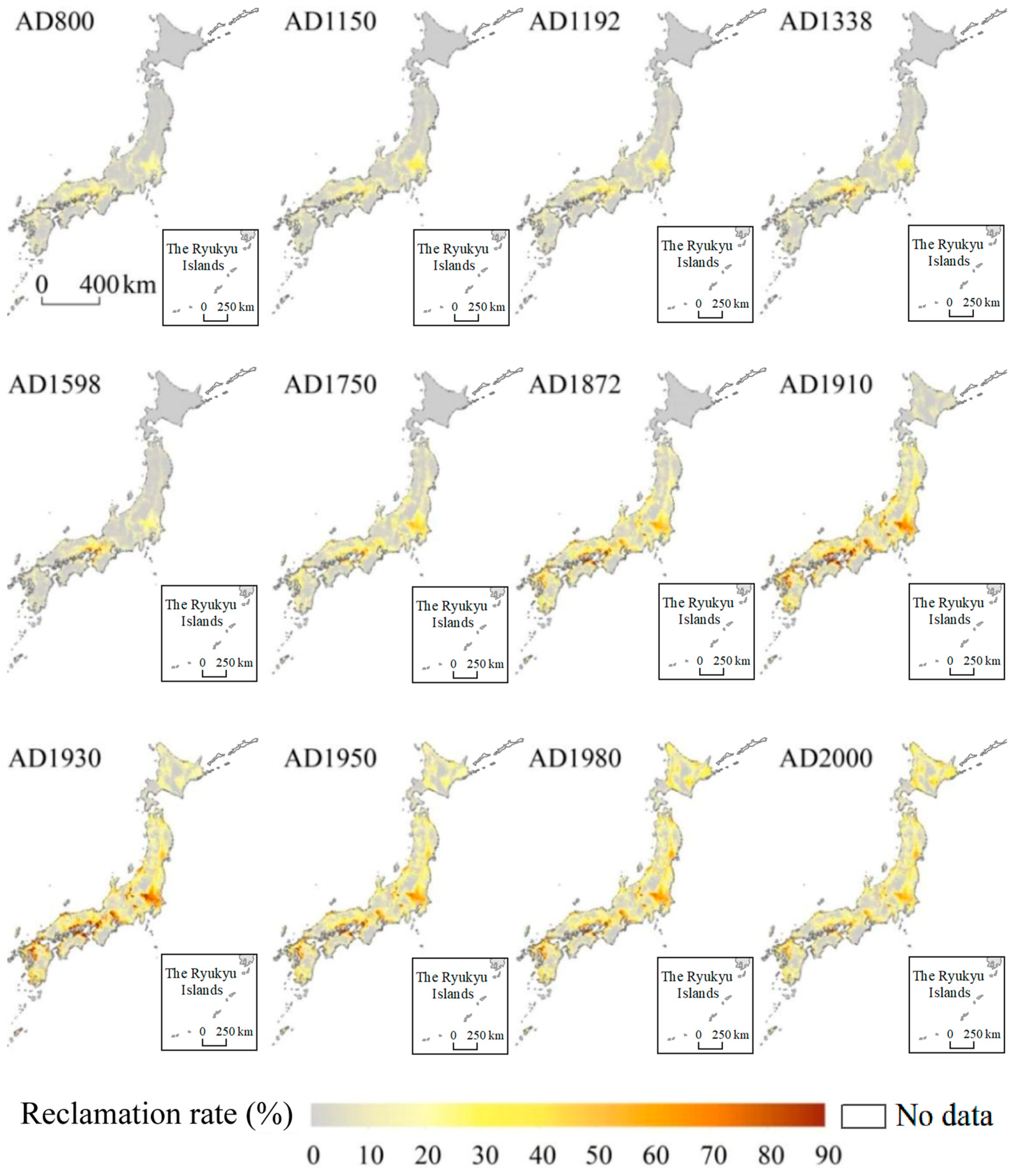

3.2. Spatial Pattern Changes of Cropland Cover

4. Discussion

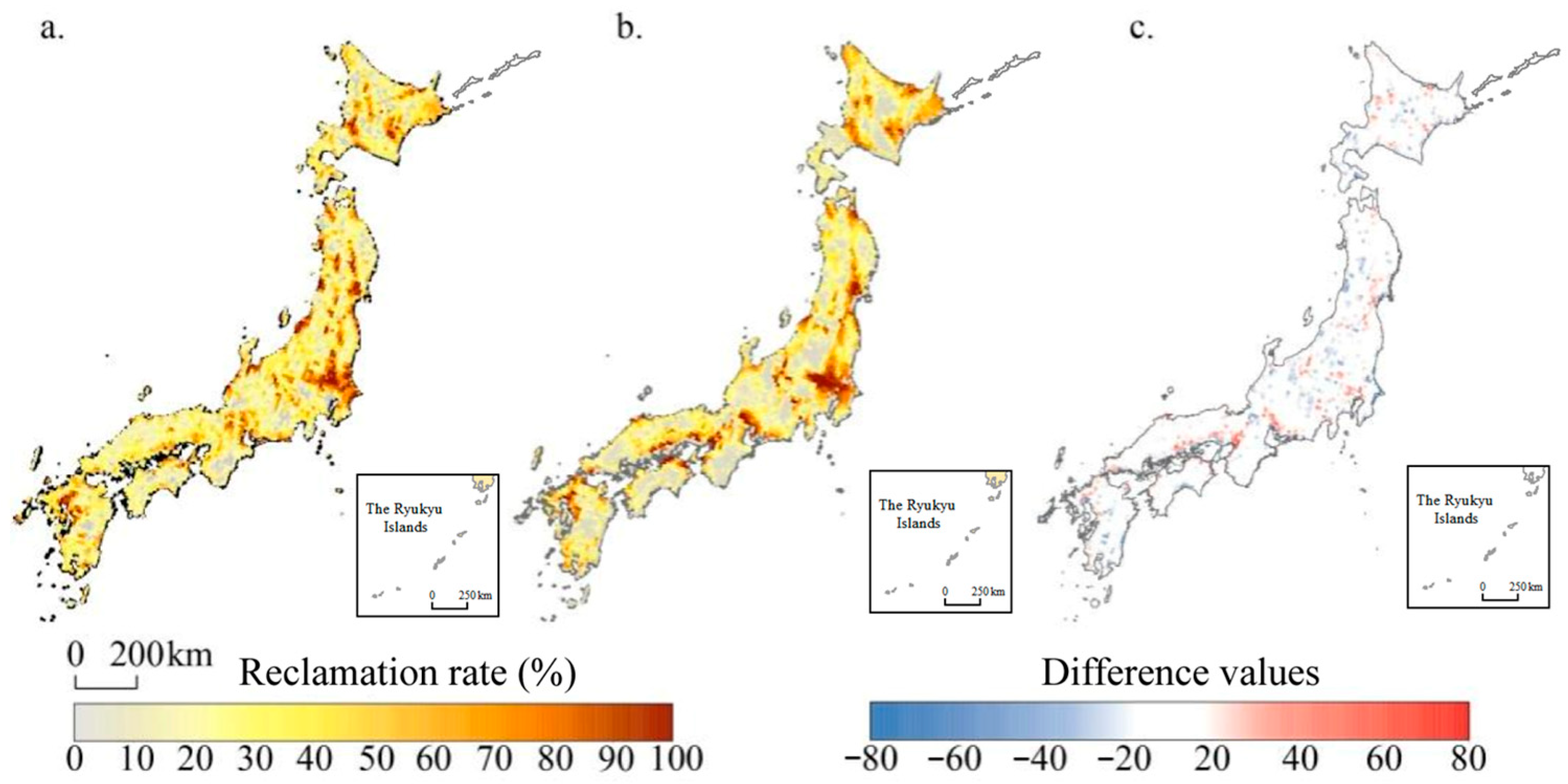

4.1. Comparison with Satellite-Based Data

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.3. Uncertainty Analysis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Japan’s total cropland area has undergone four distinct phases over the past millennium: a gradual increase from 136.70 × 104 ha in 800 CE to 202.90 × 104 ha in 1338 CE, a slow decline to 177.90 × 104 ha in 1598 CE, a rapid expansion to 602.70 × 104 ha in 1940, and a sustained contraction to 486.60 × 104 ha. These shifts reflect profound transitions in Japan’s socio-ecological systems: early growth was constrained by pre-industrial agricultural technology development limits; feudal conflicts triggered medieval declines; population increase, coupled with industrialization, drove rapid modern expansion; and post-war urbanization ultimately reversed this trend. Regionally, divergent pathways emerged based on geographical and historical contingencies. Eastern regions (Tōhoku, Kantō) and Kyushu showed synchronous four-phase trajectories, whereas Hokkaido’s late-onset expansion defied the national pattern. The Kansai region’s prolonged decline and delayed peak further illustrate how regional socio-political centers experienced distinct agricultural rhythms. These spatial differences underscore that Japan’s agricultural transitions were not uniform processes but spatially articulated responses to shifting political centers, conflict zones, and development frontiers.

- (2)

- Japan’s agricultural expansion followed a distinct center-to-periphery trajectory, advancing systematically from the core Kansai and Kantō regions toward southwestern and northeastern frontiers. The analysis demonstrates three key spatial-temporal patterns: First, the persistent dominance of the Kansai and Kantō regions, where reclamation rates consistently exceeded other regions—reaching 10.90% in Kansai and 8.54% in Kantō during the early phase (800–1192 CE), and peaking at 26.67% in Kantō by the 20th century. Second, the phased expansion into peripheral regions corresponded to major socio-political transitions: Tōhoku and Kyushu showed significant growth during the Edo period (6.88% and 15.81% reclamation rates, respectively), while Hokkaidō’s development accelerated in the modern era, reaching 7.05% by 1930. Third, the 20th-century divergence between continued frontier expansion in Hokkaidō and widespread cropland contraction in other regions, where southern areas maintained approximately 20% reclamation rates while most regions declined.

- (3)

- Applying the historical cropland gridding methodology developed in this study, we allocated region-level cropland statistics for the year 2000—derived from remote sensing data—onto a 10 km × 10 km grid. The reconstructed cropland distribution shows close spatial agreement with the remote sensing-based map. Quantitatively, 69.12% of grid cells exhibit differences within ±20%, while only 0.15% exceed ±80% deviation. This high level of consistency validates both the feasibility of the gridding reconstruction method and the reliability of the resulting cropland data product.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Stocker, B.D.; Zhang, Z.; Malhotra, A.; Melton, J.R.; Poulter, B.; Kaplan, J.O.; Klein Goldewijk, K.; Siebert, S.; Minayeva, T. Extensive global wetland loss over the past three centuries. Nature 2023, 614, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.C.; Gauthier, N.; Klein Goldewijk, K.; Bird, R.B.; Boivin, N.; Díaz, S.; Fuller, D.Q.; Gill, J.L.; Kaplan, J.O.; Kingston, N.; et al. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023483118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, L.; Fuller, D.; Boivin, N.; Rick, T.; Gauthier, N.; Kay, A.; Marwick, B.; Armstrong, C.G.D.; Barton, C.M.; Denham, T.; et al. Archaeological assessment reveals Earth’s early transformation through land use. Science 2019, 365, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, M.J.; Morrison, K.D.; Madella, M.; Whitehouse, N. Past land use and land-cover change: The challenge of quantification at the subcontinental to global scales. Past Land Use Land Cover 2018, 26, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Ning, S.; Yan, A.; Jiang, P.; Ren, H.; Li, N.; Huo, T.; Sheng, J. Analysis of carbon emissions and ecosystem service value caused by land use change, and its coupling characteristics in the Wensu Oasis, Northwest China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.M.d.; Franceschi, M.; Panosso, A.R.; Carvalho, M.A.C.d.; Moitinho, M.R.; Martins Filho, M.V.; Oliveira, D.M.d.S.; Freitas, D.A.F.d.; Yamashita, O.M.; La Scala, N., Jr. Effects of land use changes on CO2 emission dynamics in the Amazon. Agronomy 2025, 15, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, R.; Pielke, R.A., Sr.; Hubbard, K.G.; Niyogi, D.; Dirmeyer, P.A.; McAlpine, C.; Carleton, A.M.; Hale, R.; Gameda, S.; Beltrán-Przekurat, A.; et al. Land cover changes and their biogeophysical effects on climate. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 929–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Defries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Estimating historical changes in global land cover: Croplands from 1700 to 1992. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1999, 13, 997–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, J.; Reick, C.; Raddatz, T.; Claussen, M. A reconstruction of global agricultural areas and land cover for the last millennium. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 2008, 22, GB3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Krumhardt, K.M.; Ellis, E.C.; Ruddiman, W.F.; Lemmen, C.; Klein Goldewijk, K. Holocene carbon emissions as a result of anthropogenic land cover change. Holocene 2011, 21, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; Beusen, A.; Doelman, J.; Stehfest, E. Anthropogenic land use estimates for the Holocene-HYDE 3.2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 927–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Wang, J.; Clinton, N.; Bai, Y.; Liang, S. Annual dynamics of global land cover and its long-term changes from 1982 to 2015. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1217–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.W.; Yu, L.; Li, X.C.; Chen, M.; Li, X.; Hao, P.Y.; Gong, P. A 1 km global cropland dataset from 10,000 BCE to 2100 CE. Earth Syst Sci Data 2021, 13, 5403–5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tian, P.; Luo, H.; Hu, T.; Dong, B.; Cui, Y.; Khan, S.; Luo, Y. Impacts of land use and land cover changes on regional climate in the Lhasa River basin, Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Krumhardt, K.M.; Zimmermann, N.E. The effects of land use and climate change on the carbon cycle of Europe over the past 500 years. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, R.; Prestele, R.; Verburg, P.H. A global assessment of gross and net land change dynamics for current conditions and future scenarios. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2018, 9, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.J.; Wei, L.; Wang, B.; Yu, L. Contrasting influences of biogeophysical and biogeochemical impacts of historical land use on global economic inequality. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; He, F.N.; Li, S.C.; Li, M.J.; Wu, P.F. A new estimation of carbon emissions from land use and land cover change in China over the past 300 years. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Jansson, U.; Ye, Y.; Widgren, M. The spatial and temporal change of cropland in the Scandinavian Peninsula during 1875–1999. Reg. Environ. Change 2013, 13, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Krumhardt, K.M.; Gaillard, M.J.; Sugita, S.; Trondman, A.K.; Fyfe, R.; Marquer, L.; Mazier, F.; Nielsen, A.B. Constraining the deforestation history of Europe: Evaluation of historical land use scenarios with pollen-based land cover reconstructions. Land 2017, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.Y.; Fang, X.Q.; Yang, L.E. Comparison of the HYDE cropland data over the past millennium with regional historical evidence from Germany. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; He, F.N.; Zhang, X.Z.; Zhou, T.Y. Evaluation of global historical land use scenarios based on regional datasets on the Qinghai-Tibet Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.Q.; Zhao, W.Y.; Zhang, C.P.; Zhang, D.Y.; Wei, X.Q.; Qiu, W.L.; Ye, Y. Methodology for credibility assessment of historical global LUCC datasets. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.S.; He, F.N.; Yang, F.; Li, S.C. Uncertainties of global historical land use scenarios in past-millennium cropland reconstruction in China. Quat. Int. 2022, 641, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.J.; He, F.N.; Zhao, C.S.; Yang, F. Evaluation of global historical cropland datasets with regional historical evidence and remotely sensed satellite data from the Xinjiang area of China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Krumhardt, K.M.; Zimmermann, N. The prehistoric and preindustrial deforestation of Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009, 28, 3016–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, R.; Herold, M.; Verburg, P.H.; Clevers, J.G.P.W. A high-resolution and harmonized model approach for reconstructing and analyzing historic land changes in Europe. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.L. The application of ANN-FLUS model in reconstructing historical cropland distribution changes: A case study of Vietnam from 1885 to 2000. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1473–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ye, Y.; Fang, X.Q.; Zhang, C.P.; Zhang, D.Y. Reconstruction dataset of cropland change in five Central Asian countries over the last millennium (1000–2000). J. Glob. Change Data Discov. 2022, 6, 374–385. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.N.; Yang, F.; Zhao, C.S.; Li, S.C.; Li, M.J. Spatially explicit reconstruction of cropland cover for China over the past millennium. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 53, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Lu, C.Q. Historical cropland expansion and abandonment in the continental U.S. during 1850 to 2016. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.C.P.; Pimenta, F.M.; Santos, A.B.; Costa, M.H.; Ladle, R.J. Patterns of land use, extensification, and intensification of Brazilian agriculture. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 2887–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.Q.; Banger, K.; Bo, T.; Dadhwal, V.K. History of land use in India during 1880–2010: Large-scale land transformations reconstructed from satellite data and historical archives. Glob. Planet. Change 2014, 121, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, J.; Fang, X.Q.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhao, Z.L.; Wu, Z.L.; Lu, Y.J.; Li, B.B. Reconstruction of cropland change in European countries using integrated multisource data since AD 1800. Boreas 2023, 52, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, H.; He, F.N.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhou, S.N.; Dong, G.P. A 1000-year history of cropland cover change along the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 921–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Liu, Y.T.; Li, J.R.; Zhang, X.Z. Mapping cropping patterns in the North China Plain over the past 300 years and an analysis of the drivers of change. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 2074–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, E.P.; Richards, J.F. Historical analysis of changes in land use and carbon stock of vegetation in South and Southeast Asia. Can. J. For. Res. 1991, 21, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himiyama, Y. Land use/cover changes in Japan: From the past to the future. Hydrol. Process. 1998, 12, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Takara, K.; He, B.; Razafindrabe, B.H. Reconstruction assessment of historical land use: A case study in the Kamo River basin, Kyoto, Japan. Comput. Geosci. 2014, 63, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T. A History of the Japanese Shōen System; Yuhikaku Publishing Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1979; p. 137. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R100000039-I1716585 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Takeuchi, R. History of Land Systems, Vol. I; Yamakawa Shuppansha: Tokyo, Japan, 1973; pp. 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, M. An Overview of the History of Japanese Shōden; Yoshikawa Kōbunkan: Tokyo, Japan, 1959; pp. 234–235, 257–259. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R100000002-I000000963726 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Miyakawa, M. On the Taikō Kenchi; Ochanomizu Shobō: Tokyo, Japan, 1959; p. 359. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R100000039-I2468176 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Kanzaki, A. Kenchi; Nihon Shinsyo Publishing Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1983; pp. 15, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Treasury. Great Japan Tax Records, Vol. 1 & 2; Choyokai: Tokyo, Japan, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Meiji Financial History Compilation Society (Ed.) Meiji Financial History, Vol. 5; Yoshikawa Kōbunkan: Tokyo, Japan, 1954; Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R100000039-I1449175 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Fukushima, M. Chiso Kaisei; Yoshikawa Kōbunkan: Tokyo, Japan, 1995; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Kito, H. Regional population in Japan before the Meiji Period. Sophia Econ. Rev. 1996, 41, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Japan’s National Land Agency. Long-Term Time Series Analysis of Population Distribution in the Japanese Archipelago; Japan’s National Land Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 1974; Available online: https://www.kok.or.jp/publication/pdf/tokuColum_202404.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Minami, K. A study on the Edo society in the late Tokugawa Period. Jpn. Hist. Res. 1980, 218, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya, N. The History of Japan’s Population; Shikai Shobō: Tokyo, Japan, 1942; pp. 1–261. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R100000074-IALIS_QQ00820837 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Tamagawa, H. A History of Japanese Farmers; Seibido Shuppan Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1935; pp. 461–463. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/sehs/5/12/5_KJ00002437678/_article/-char/ja/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Li, M.J.; He, F.N.; Zhao, C.S.; Yang, F. Reconstruction and dynamic evolution characteristics of cropland area in Japan over the past millennium. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 2573–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.K.; Cong, S.Y.; Meng, C.F. Japanese Agricultural Geography; Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.S.; Zheng, J.Y.; He, F.N. Gridding cropland data reconstruction over the agricultural region of China in 1820. J. Geogr. Sci. 2009, 19, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.L. Japanese Agricultural Economy; Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; Beusen, A.; Van Drecht, G.; De Vos, M. The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human-induced global land-use change over the past 12,000 years. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Difference Level (%) | <−80 | −80~−70 | −70~−60 | −60~−50 | −50~−40 | −40~−30 | −30~−20 | −20~−10 | −10~0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of grid numbers (%) | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 1.06 | 2.67 | 5.11 | 8.55 | 15.18 | 19.31 |

| Difference level (%) | 0~10 | 10~20 | 20~30 | 30~40 | 40~50 | 50~60 | 60~70 | 70~80 | >80 |

| Proportion of grid numbers (%) | 23.53 | 11.10 | 6.92 | 3.36 | 1.38 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Zhao, C.; He, F.; Li, S.; Yang, F. Reconstructing Millennial-Scale Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Japan’s Cropland Cover. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122834

Li M, Zhao C, He F, Li S, Yang F. Reconstructing Millennial-Scale Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Japan’s Cropland Cover. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122834

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Meijiao, Caishan Zhao, Fanneng He, Shicheng Li, and Fan Yang. 2025. "Reconstructing Millennial-Scale Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Japan’s Cropland Cover" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122834

APA StyleLi, M., Zhao, C., He, F., Li, S., & Yang, F. (2025). Reconstructing Millennial-Scale Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Japan’s Cropland Cover. Agronomy, 15(12), 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122834