Biocontrol and Microscopic Observations of Bacillaceae Strains Against Root-Knot Nematodes on Cotton, Soybean and Tomato: A Brazilian Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Meloidogyne spp. Isolates and Bacillaceae Strains

2.2. Rhizocompetence of Bacillaceae-Commercial and Non-Commercial Strains

2.3. Evaluation of the Biocontrol of Commercial and Non-Commercial Bacillaceae Strains Against Meloidogyne spp. in Greenhouse (S = 15°43′46.6″, W = 47°54′00.5″) Conditions

2.3.1. Control of Meloidogyne incognita on Cotton

2.3.2. Control of Meloidogyne javanica and M. incognita in Soybean

2.3.3. Control of M. incognita on Tomato Plants

2.3.4. Evaluation of Bacteria in Reducing the Penetration of M. javanica Second-Stage Juveniles (J2) and the Histopathological Technique in Soybean Roots

3. Results

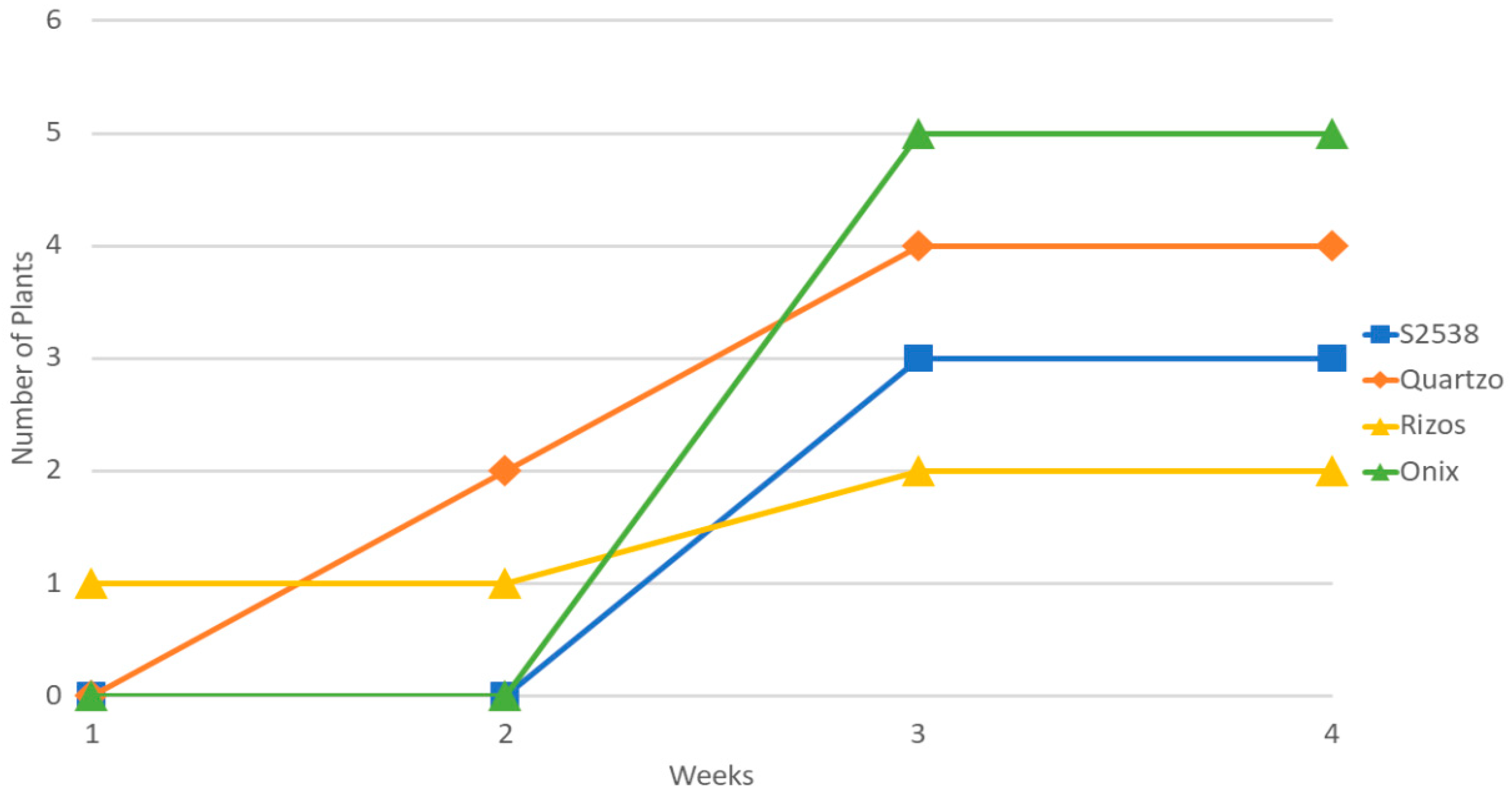

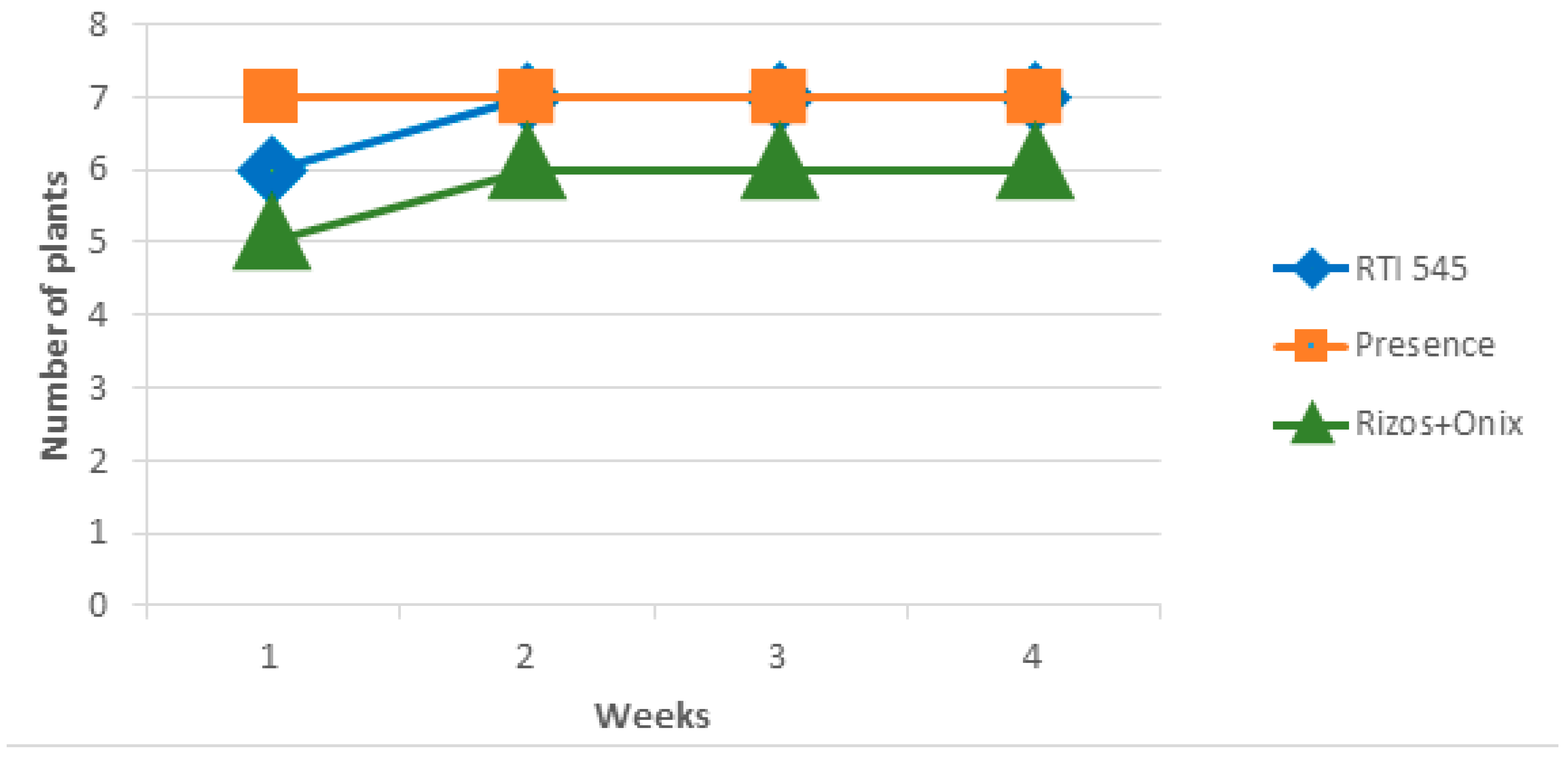

3.1. Rhizocompetence of Bacillaceae Bacteria on Commercial and Non-Commercial Strains

3.2. Evaluation of the Biocontrol of Commercial and Non-Commercial Bacillaceae Strains Against Meloidogyne spp. in Greenhouse Conditions

3.2.1. Cotton

3.2.2. Soybean

3.2.3. Tomato

3.3. Comparative Histopathology of M. javanica in Soybean Roots Treated or Not with Bacillus spp.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moens, M.; Perry, R.N.; Starr, J.L. Meloidogyne species-a diverse group of novel and important plant parasites. In Root-Knot Nematodes; Perry, R.N., Moens, M., Starr, J.L., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, J.B.; Pereira, R.B.; Suinaga, F.A. Manejo de nematoides na cultura do tomate. Circ. Téc. Embrapa Hortaliças 2014, 132, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, W.P.; Garcia, A.; Silva, J.F.V.; Carneiro, G.E.S. Nematoides em soja: Identificação e controle. Circ. Téc. Embrapa Soja 2010, 76, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Galbieri, R.; Inomoto, M.M.; Silva, R.A.; Asmus, G.L. Manejo de nematoides na cultura do algodão. In Manual de Boas Práticas; AMPA-IMA: Cuiabá, Brazil, 2015; pp. 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R.F.; Galbieri, R.; Asmus, G.L. Nematode parasites of cotton and other tropical fibre crops. In Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture; Luc, M., Sikora, R.A., Bridge, J., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2022; pp. 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawi, G.S.; Widmer, T.L. Impact of soil health management practices on soilborne pathogens, nematodes and root diseases of vegetable crops. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2000, 15, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, D.L.; Fourie, H.H.; Moens, M. Current and future management strategies in resource-poor farming. In Root-Knot Nematodes; Perry, R.N., Moens, M., Starr, J.L., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 444–475. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, G.R. Biological Control of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes, 2nd ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2019; p. 510. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, R.M.D.G.; Monteiro, T.S.A.; Eckstein, B.; Freitas, L.G. Controle biológico de nematoides fitoparasitas. In Controle Biológico de Pragas da Agricultura, 1st ed.; Fontes, E.M.G., Valadares-Inglis, M.C., Eds.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; pp. 371–399. [Google Scholar]

- Andreata, M.F.L.; Alves, S.M.; Andrade, G.; Bueno, A.; Ventura, M.U.; Marcondes De Almeida, J.E.; Fonseca, E.A.; Mosela, M.; Simionato, A.; Robaina, R.R.; et al. The Current Increase and Future Perspectives of the Microbial Pesticides Market in Agriculture: The Brazilian Example. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1574269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, E.M.G.; Pires, C.S.S.; Sujii, E.R. Estratégias de uso e histórico. In Controle Biológico de Pragas da Agricultura, 1st ed.; Fontes, E.M.G., Valadares-Inglis, M.C., Eds.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mariutto, M.; Ongena, M. Molecular patterns of rhizobacteria involved in plant immunity elicitation. In Advances in Botanical Research; Bais, H., Sherrier, J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 75, pp. 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, R.A.; Schäfer, K.; Dababat, A.A. Modes of action associated with microbially induced in planta suppression of plant-parasitic nematodes. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2007, 36, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Heuer, H.; Hallmann, J. Bacterial antagonists of fungal pathogens also control root-knot nematodes by induced systemic resistance of tomato plants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, R.M.D.G.; Souza, C.F.B.; Mattos, V.S.; Correia, V.R. Molecular techniques for root-knot nematode identification. In Plant-Nematode Interactions; Molinari, S., Ed.; Springer Protocols: Bari, Italy, 2024; pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, B.P.V.; Aguilar-Vildoso, C.I.; Melo, I.S. Visualização in vitro da colonização de raízes por rizobactérias. Summa Phytopathol. 2006, 32, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, R.S.; Barker, K.R. A comparison of methods of collecting inocula of Meloidogyne spp., including a new technique. Plant Dis. Rep. 1973, 57, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Boneti, J.I.S.; Ferraz, S. Modificação do método de Hussey & Barker para extração de ovos de Meloidogyne exigua de raízes de cafeeiro. Fitopatol. Bras. 1981, 6, 553. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D.F. Sisvar: A computer statistical analysis system. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2011, 35, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd Jr, D.W.; Kirkpatrick, T.; Barker, K.R. An improved technique for clearing and staining plant tissues for detection of nematodes. J. Nematol. 1983, 15, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Pegard, A.; Brizzard, G.; Fazari, A.; Soucaze, O.; Abad, P.; Djian-Caporalino, C. Histological characterization of resistance to different root-knot nematode species related to phenolics accumulation in Capsicum annuum. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, J.; Davies, K.G.; Sikora, R. Biological control using microbial pathogens, endophytes and antagonists. In Root-Knot Nematodes; Perry, R.N., Moens, M., Starr, J.L., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 380–411. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Wang, Y.F.; Tang, Y.Y.; Chen, S.L.; Yan, S.Z. Endophytic Bacillus cereus effectively controls Meloidogyne incognita on tomato plants through rapid rhizosphere occupation and repellent action. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, F.C.; Alves, G.C.S.; Giband, M.; Gomes, A.C.M.M.; Sousa, F.R.; Mattos, V.S.; Barbosa, V.H.S.; Barroso, P.A.V.; Nicole, M.; Peixoto, J.R.; et al. New sources of resistance to Meloidogyne incognita race 3 in wild cotton accessions and histological characterization of the defense mechanisms. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.M.L.; Cares, J.E.; Perina, F.J.; Nascimento, G.F.; Mendonça, J.S.F.; Moita, A.W.; Castagnone-Sereno, P.; Carneiro, R.M.D.G. Diversity of Meloidogyne incognita populations from cotton and aggressiveness to Gossypium spp. accessions. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.F.B.; Suassuna, N.D.; Mattos, V.S.; Cruz, A.L.P.; Cares, J.E.; Carneiro, R.M. Residual-resistance effect of two known QTLs in cotton genotypes on Meloidogyne enterolobii reproduction. Nematology 2025, 27, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, M.; Tefera, T.; Sakhuja, P.K. Effect of formulation of Bacillus firmus on root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita infestation and growth of tomato plants in the greenhouse and nursery. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2009, 100, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, H.; Xia, L.; Li, L.; Sun, M.; Yu, Z. Systemic nematicidal activity and biocontrol efficacy of Bacillus firmus against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgham, J.L.; Sikora, R.A. Biological control potential and modes of action of Bacillus megaterium against Meloidogyne graminicola on rice. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, J.W.; Yao, J.H.; Feng, H.; Wei, L.H. Effects of Bacillus cereus strain Jdm1 on Meloidogyne incognita and the bacterial community in tomato rhizosphere soil. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.M.C.; D’Arc de Lima, R.; Carneiro, R.M.D.G. Variabilidade isoenzimática de populações de Meloidogyne spp. provenientes de regiões brasileiras produtoras de soja. Nematol. Bras. 2003, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, J.; Quadt-Hallmann, A.; Miller, W.G.; Sikora, R.A.; Lindow, S.E. Endophytic colonization of plants by the biocontrol agent Rhizobium etli G12 in relation to Meloidogyne incognita infection. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, M. Microbial inoculation of seed for improved crop performance: Issues and opportunities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5729–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatments | Bacillus spp. | Concentration | Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| S2538 1 | P. aryabhattai | 1.0 × 1010 UFC/mL | 3 mL/kg of seed |

| S2538 1 | P. aryabhattai | 1.0 ×108 UFC/mL | 20 mL in 2 Kg of soil |

| Presence | Bacillus subtilis + B. licheniformis | 1.0 × 1011 UFC/mL | 1 g/1 kg of seed |

| Quartzo® ST | B. licheniformis + B. subtilis | 1.0 × 1011 UFC/g + 1.0 × 1011 UFC/g | 20 g/3 kg of seed |

| Quartzo® Drench | B. licheniformis + B. subtilis | 1.0 × 1011 UFC/g + 1.0 × 1011 UFC/g | 200 g/ha |

| Onix® | B. velezensis | 1.0 × 109 UFC/mL | 3 mL/kg of seed |

| Rizos® | B. subtilis | 3.0 × 109 UFC/mL | 2 mL/kg of seed |

| RTI 545 | B. thuringiensis | 2.5 × 1010 UFC/mL | 1.5 mL–6 mL/kg of seed |

| Untreated control | distilled water | NA | 3 mL/kg of seed |

| Treatment | RF 1 | SDB (g) 1 | RFB (g) 1 | EGR 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

60

DAI |

120

DAI |

60

DAI |

120

DAI |

60

DAI |

120

DAI |

60

DAI |

120

DAI | |

| Untreated control | 9.11 a | 104.8 a | 19.87 a | 45.06 a | 23.75 b | 90.56 a | 2003.92 a | 6338.84 a |

| S2538 | 7.59 a | 58.56 | 20.25 a | 45.75 a | 27.37 b | 67.75 b | 1418.72 a | 4270.9 a |

| Onix® | 4.59 a | 49.86 b | 18.87 a | 43.7 a | 33.0 a | 67.81 b | 692.16 b | 3820.03 a |

| Quartzo® | 8.91 a | 43.15 b | 18.12 a | 40.81 a | 33.06 a | 73.81 b | 1355.18 a | 4498.57 a |

| Rizos® | 7.62 a | 81.56 a | 18.87 a | 44.6 a | 31.25 a | 65.16 b | 1395.42 a | 6085.37 a |

| CV | 4.81 | 7.18 | 2.46 | 8.13 | 7.65 | 18.02 | 22.5 | 25.4 |

| Treatment | RF 1 | SDB (g) 1 | RFB (g) 1 | EGR 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 DAI | 120 DAI | 60 DAI | 120 DAI | 60 DAI | 120 DAI |

60

DAI |

120

DAI | |

| Untreated control | 13.9 a | 85.9 a | 40.8 a | 53.5 a | 33.8 a | 124.5 a | 4212.4 a | 6889.8 a |

| S2538 | 8.4 b | 74.6 a | 41.9 a | 55.5 a | 37.5 a | 95.8 b | 2317 b | 8138.7 b |

| Onix® | 11.4 b | 188.0 a | 38.6 a | 52.6 a | 36.1 a | 99.6 b | 3685.2 b | 18,195.6 b |

| Quartzo® drench | 8.5 b | 152.4 a | 38.3 a | 51.0 a | 37.0 a | 106.5 a | 2586.5 b | 14,688.4 a |

| Quartzo® ST | 10.2 a | 144.9 a | 40.3 a | 52.1 a | 42 a | 89.3 b | 2513.7 b | 15,700.1 b |

| Rizos® | 18.6 a | 104.6 a | 41.8 a | 49.4 a | 36 a | 108.1 a | 3196.4 a | 13,524.2 a |

| CV | 7.43 | 7.92 | 6.77 | 7.19 | 9.14 | 20.79 | 22.7 | 20.79 |

| Bioassay 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | RF 1 | EGR 1 | RFB (g) 1 |

| Untreated control | 9.43 a | 2368.92 a | 19.9 a |

| Rugby® | 4.30 b | 1176.97 a | 18.25 a |

| Presence® | 9.00 a | 3194.86 a | 14.08 a |

| RTI 545 (3 mL) | 5.42 a | 1980.90 a | 13.68 a |

| Onix + Rizos | 3.11 b | 1245.20 a | 12.50 a |

| CV | 20.23 | 31.26 | 14.03 |

| Bioassay 2 | |||

| Treatments | RF 1 | EGR 1 | RFB (g) 1 |

| Untreated control | 17.36 a | 3297.24 a | 26.33 a |

| Marshal® | 3.75 c | 3655.55 c | 5.13 b |

| Presence® | 14.57 a | 2658.79 a | 27.41 a |

| RTI 545 (3 mL) | 16.83 a | 2928.34 a | 28.75 a |

| Onix + Rizos | 9.27 b | 1590.76 b | 29.16 a |

| CV | 29.80 | 36.49 | 30.65 |

| Bioassay 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | RF 1 | EGR 1 | RFB (g) 1 |

| Untreated control | 8.23 a | 4145.15 a | 9.93 a |

| Rugby® | 6.24 a | 4120.22 a | 7.57 a |

| Presence® | 7.08 a | 3348.39 a | 10.57 a |

| RTI 545 (3 mL) | 5.06 a | 3035.60 a | 8.34 a |

| Onix + Rizos | 7.28 a | 4348.54 a | 8.37 a |

| CV | 29.86 | 32.25 | 25.82 |

| Bioassay 2 | |||

| Treatments | RF 1 | EGR 1 | RFB (g) 1 |

| Untreated control | 18.40 a | 6737.36 a | 13.66a |

| Marshal®Start | 3.85 b | 3977.95 a | 4.84 b |

| Presence® | 13.74 a | 8591.93 a | 8.00 b |

| RTI 545 (3 mL) | 15.12 a | 5160.11 a | 14.66 a |

| Onix + Rizos | 13.27 a | 9267.65 a | 7.16 b |

| CV | 22.05 | 31.31 | 25.84 |

| Bioassay 1-Untreated | Bioassay 1-Treated with RTI 545 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicates | RFB (g) 1 | EGR 1 | RF 1 | RFB (g) 1 | EGR 1 | RF 1 |

| 1 | 27 | 4440.4 | 24.4 | 52 | 321.0 | 3.3 |

| 2 | 34 | 4412.0 | 30.0 | 60.5 | 441.5 | 5.4 |

| 3 | 39.5 | 4895.0 | 38.7 | 34.5 | 966.0 | 6.7 |

| 4 | 21.5 | 6512.0 | 28.0 | 45.5 | 1245.2 | 11.3 |

| 5 | 35 | 3524.0 | 24.7 | 50 | 933.0 | 9.3 |

| Means | 31.4 | 4756.7 | 29.2 | 48.5 | 781.3 | 7.2 |

| Bioassay 2-Untreated | Bioassay 2-Treated with RTI 545 | |||||

| Replicates | RFB (g) 1 | EGR 1 | RF 1 | RFB (g) 1 | EGR 1 | RF 1 |

| 1 | 29.0 | 6490.2 | 24.7 | 63.5 | 787.0 | 10.0 |

| 2 | 46.5 | 2867.0 | 26.7 | 40.1 | 1083.2 | 8.7 |

| 3 | 30.1 | 4444.2 | 26.7 | 34.3 | 882.0 | 6.1 |

| 4 | 23.0 | 4348.0 | 20.0 | 33.4 | 1210.2 | 8.1 |

| 5 | 29.2 | 6430.7 | 37.3 | 24.2 | 417.0 | 2.0 |

| Means | 29.6 | 4916.0 | 27.1 | 39.1 | 875.9 | 7.0 |

| Treatments | RFB | EGR | RF | % of Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated control | 33.4 b 1 | 10,190.56 a | 69.27 a | _ |

| 3 mL RTI 545/1 kg of seeds | 71.1 a | 3310.92 a | 47.06 a | 32.07 |

| 5 mL RTI 545/1 kg of seeds | 43.3 b | 1400.74 b | 8.99 b | 87.0 |

| 5 mL RTI 545 + 5 mL H2O/1 kg of seeds | 60.5 a | 720.23 b | 8.70 b | 87.4 |

| 10 mL RTI 545/1 kg | 18.1 c | 3590.09 | 12.93 b | _ |

| CV | 30.7 | 26.5 | 20.2 | - |

| Treatments | RFB | EGR | RF | % of Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated control | 60.90 b 1 | 2605.65 a | 44.09 a | - |

| S2538 RT * | 68.38 b | 1103.10 b | 24.14 c | 45.25 |

| S2538 DT ** | 59.38 b | 1113.46 b | 21.64 c | 50.92 |

| RTI 545 RT | 87.5 a | 792.61 c | 23.05 c | 47.70 |

| RTI 545 DT | 57.37 b | 1880.47 b | 36.88 b | 16.33 |

| CV | 25.4 | 32.5 | 28.3 | - |

| Treatments | RFB | EGR | RF | % of Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated control | 44.00 b 1 | 1886.3 a | 25.4 a | - |

| S2538 DT ** | 74.00 a | 658.3 c | 15.2 b | 40.17 |

| S2538 ST *** | 56.3 b | 1246.3 b | 24.5 a | 3.78 |

| RTI 545 ST | 42.50 b | 665.7 c | 9.5 c | 62.81 |

| CV | 28.5 | 38.7 | 26.3 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mattos, V.S.; Torres, C.A.R.; Santos, M.F.A.; Gomes, A.C.M.M.; Ribeiro, N.A.; Hoepers, L.M.L.; Eckstein, B.; Carneiro, R.M.D.G. Biocontrol and Microscopic Observations of Bacillaceae Strains Against Root-Knot Nematodes on Cotton, Soybean and Tomato: A Brazilian Experience. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122828

Mattos VS, Torres CAR, Santos MFA, Gomes ACMM, Ribeiro NA, Hoepers LML, Eckstein B, Carneiro RMDG. Biocontrol and Microscopic Observations of Bacillaceae Strains Against Root-Knot Nematodes on Cotton, Soybean and Tomato: A Brazilian Experience. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122828

Chicago/Turabian StyleMattos, Vanessa S., Caio A. R. Torres, Marcilene F. A. Santos, Ana C. M. M. Gomes, Nanci A. Ribeiro, Lívia M. L. Hoepers, Barbara Eckstein, and Regina M. D. G. Carneiro. 2025. "Biocontrol and Microscopic Observations of Bacillaceae Strains Against Root-Knot Nematodes on Cotton, Soybean and Tomato: A Brazilian Experience" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122828

APA StyleMattos, V. S., Torres, C. A. R., Santos, M. F. A., Gomes, A. C. M. M., Ribeiro, N. A., Hoepers, L. M. L., Eckstein, B., & Carneiro, R. M. D. G. (2025). Biocontrol and Microscopic Observations of Bacillaceae Strains Against Root-Knot Nematodes on Cotton, Soybean and Tomato: A Brazilian Experience. Agronomy, 15(12), 2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122828