Effects of Grassland Ley Sward Diversity on Soil Potassium and Magnesium Forms in Two Contrasting Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Basic Chemical Soil Properties

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Sampling

2.5. Data Analysis

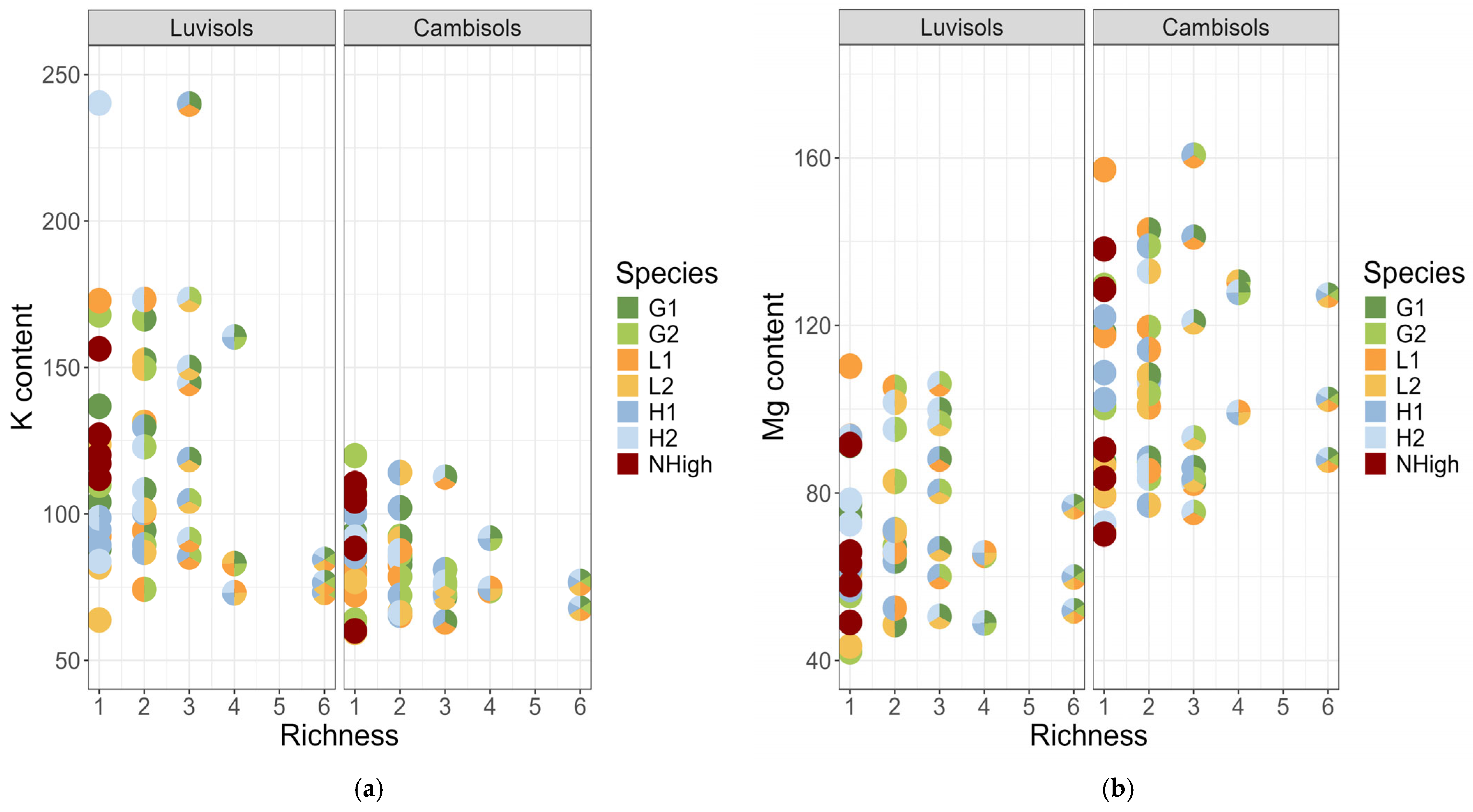

3. Results

3.1. Diversity Interaction Models

3.2. Identity Effects

3.3. Pairwise Linear Contrasts

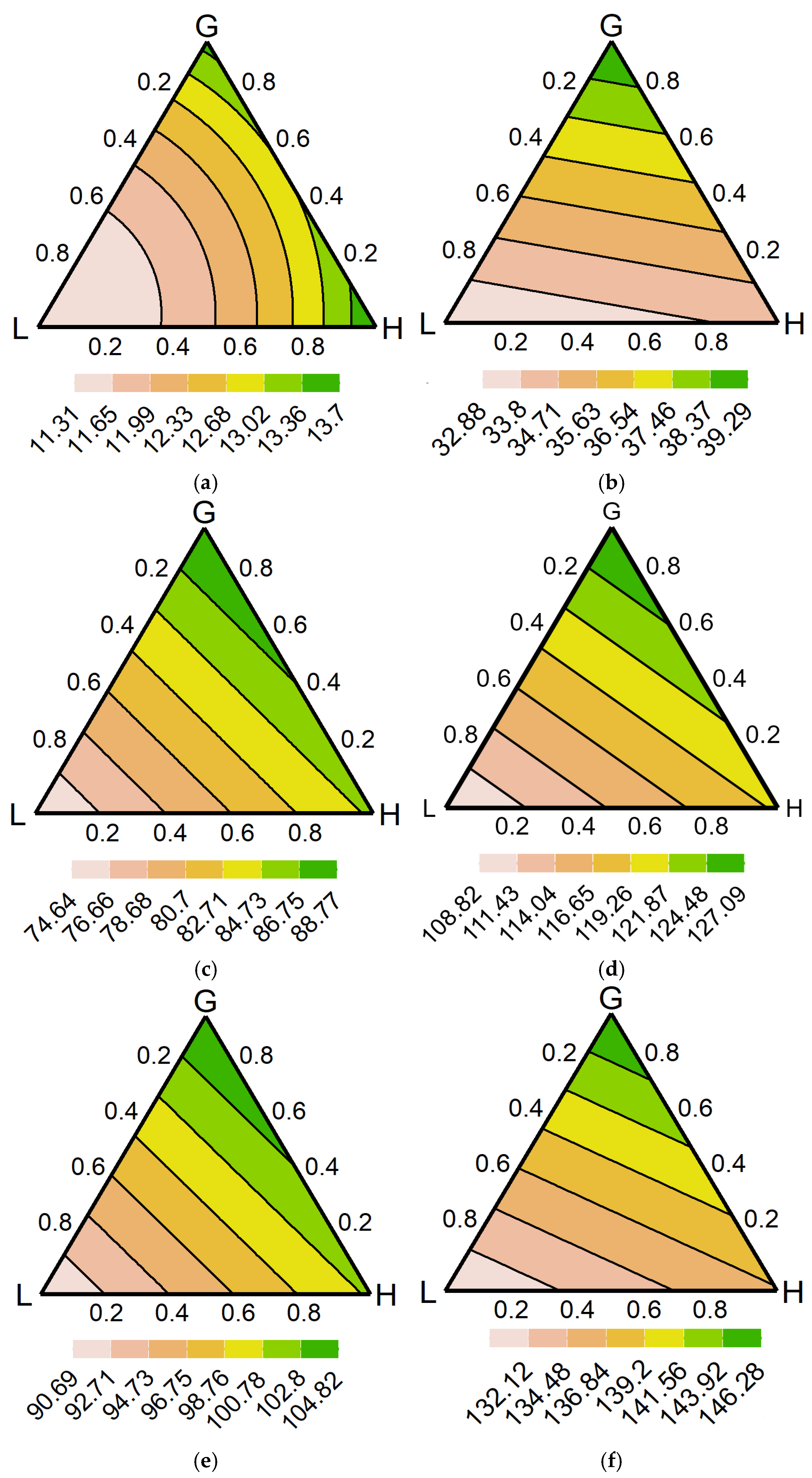

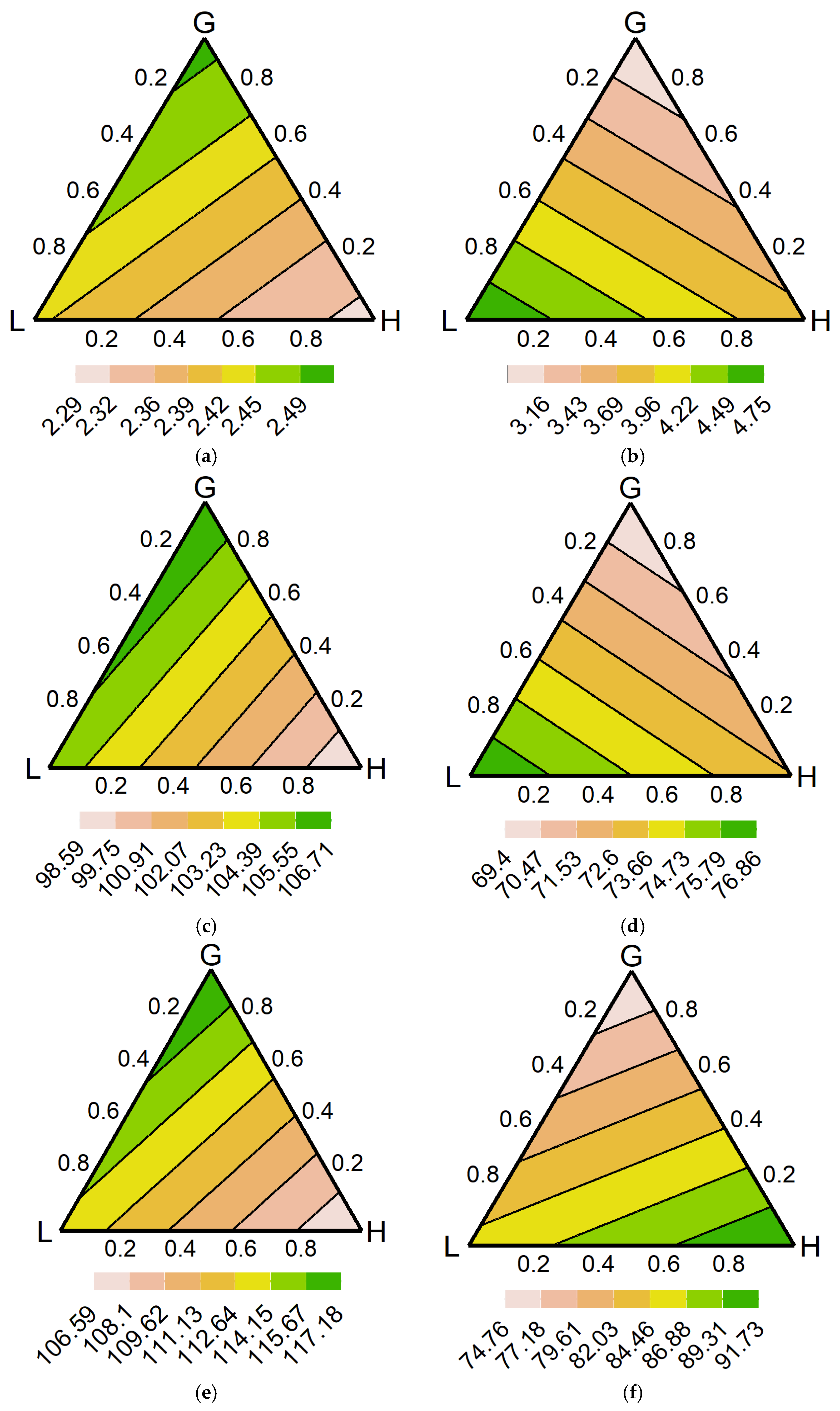

3.4. Model Predictions

4. Discussion

4.1. Species Richness Effect

4.2. Differences Between Soil Types

4.3. Differences Among Extractants

4.4. Optimal Range of Communities

4.5. Nutrient Cycling Complexity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/LC (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Golińska, B.; Vishwakarma, R.; Brophy, C.; Goliński, P. Positive effects of plant diversity on dry matter yield while maintaining a high level of forage digestibility in intensively managed grasslands across two contrasting environments. Grass Forage Sci. 2023, 78, 438–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, S.; Finger, R.; Leiber, F.; Probst, S.; Kreuzer, M.; Weigelt, A.; Buchmann, N.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M. Plant diversity effects on forage quality, yield and revenues of semi-natural grasslands. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, M.; Huguenin-Elie, O.; Lüscher, A. Multispecies for multifunctions: Combining four complementary species enhances multifunctionality of sown grassland. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, S.; Velescu, A.; Leimer, S.; Weigelt, A.; Chen, H.; Eisenhauer, N.; Scheu, S.; Oelmann, Y.; Wilcke, W. Plant diversity influenced gross nitrogen mineralization, microbial ammonium consumption and gross inorganic N immobilization in a grassland experiment. Oecologia 2020, 193, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, J.; Mortensen, T.; Søegaard, K. Root biomass and carbon storage in differently managed multispecies temporary grasslands. Grass Forage Sci. Eur. 2012, 17, 610–612. [Google Scholar]

- Obasoro, O.; Shackleton, J.; Grace, C.; Kennedy, J.; Oram, N.J.; Sheridan, H.; Schmidt, O.; De Goede, R.; Hoffland, E.; Obasoro, O.; et al. Multispecies swards improve nitrogen use efficiency and reduce nitrogen surplus in agricultural grasslands. Plant Soil 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; MacE, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüscher, A.; Barkaoui, K.; Finn, J.A.; Suter, D.; Suter, M.; Volaire, F. Using plant diversity to reduce vulnerability and increase drought resilience of permanent and sown productive grasslands. Grass Forage Sci. 2022, 77, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, W.; Dupont, Y.L.; Søegaard, K.; Eriksen, J. Optimizing yield and flower resources for pollinators in intensively managed multi-species grasslands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 302, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikoyi, I.; Grange, G.; Finn, J.A.; Brennan, F.P. Plant diversity enhanced nematode-based soil quality indices and changed soil nematode community structure in intensively-managed agricultural grasslands. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2023, 118, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komainda, M.; Muto, P.; Isselstein, J. Interaction of multispecies sward composition and harvesting management on herbage yield and quality from establishment phase to the subsequent crop. Grass Forage Sci. 2022, 77, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, C.; Finn, J.A.; Lüscher, A.; Suter, M.; Kirwan, L.; Sebastià, M.T.; Helgadóttir, Á.; Baadshaug, O.H.; Bélanger, G.; Black, A.; et al. Major shifts in species’ relative abundance in grassland mixtures alongside positive effects of species diversity in yield: A continental-scale experiment. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 1210–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J.A.; Kirwan, L.; Connolly, J.; Sebastià, M.T.; Helgadottir, A.; Baadshaug, O.H.; Bélanger, G.; Black, A.; Brophy, C.; Collins, R.P.; et al. Ecosystem function enhanced by combining four functional types of plant species in intensively managed grassland mixtures: A 3-year continental-scale field experiment. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, G.; Brophy, C.; Vishwakarma, R.; Finn, J.A. Effects of experimental drought and plant diversity on multifunctionality of a model system for crop rotation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Soil Monitoring and Resilience (Soil Monitoring Law); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Weninger, T.; Ramler, D.; Bondi, G.; Asins, S.; O’Sullivan, L.; Assennato, F.; Astover, A.; Bispo, A.; Borůvka, L.; Buttafuoco, G.; et al. Do we speak one language on the way to sustainable soil management in Europe? A terminology check via an EU-wide survey. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, D. Structure and weathering of potassium containing minerals. In Proceedings of the 11th Congress of the International Potash Institute, Tokyo, Japan, 27–28 August 1978; International Potash Institute: Bern, Switzerland, 1978; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, D.L. Potassium Dynamics in Soils. In Proceedings of the Advances in Soil Science; Stewart, B.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, P.L.; Curtin, D.; Scott, C.L. An improved procedure for routine determination of reserve-K in pastoral soils. Plant Soil 2011, 341, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, M.E. Handbook of Soil Science; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; p. 2148. [Google Scholar]

- Andrist-Rangel, Y.; Edwards, A.C.; Hillier, S.; Öborn, I. Long-term K dynamics in organic and conventional mixed cropping systems as related to management and soil properties. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 122, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.L.; Huang, P.M. Physical chemistry of soil potassium. In Potassium in Agriculture; Munson, R.D., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1985; pp. 201–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser, M.; Isselstein, J. Potassium cycling and losses in grassland systems: A review. Grass Forage Sci. 2005, 60, 213–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylton, L.O.; Ulrich, A.; Cornelius, D.R. Potassium and Sodium Interrelations in Growth and Mineral Content of Italian Ryegrass. Agron. J. 1967, 59, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Niu, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Yuan, L.; Xie, J. Potassium nutrition of crops under varied regimes of nitrogen supply. Plant Soil 2010, 335, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, T.; Wall, D.P.; Casey, I.A.; Humphreys, J.; Forrestal, P.J. Integrating Soil Potassium Status and Fertilisation Strategies to Increase Grassland Production and Mitigate Potassium Management Induced Metabolic Disorders in Grazing Livestock. Soil Use Manag. 2025, 41, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M.E.; Cowan, J.A. Magnesium chemistry and biochemistry. Biometals 2002, 15, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senbayram, M.; Gransee, A.; Wahle, V.; Thiel, H. Role of magnesium fertilisers in agriculture: Plant-soil continuum. Crop Pasture Sci. 2015, 66, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Yazici, A.M. Magnesium: A forgotten element in crop production. Better Crops 2010, 94, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Staugaitis, G.; Rutkauskienė, R. Comparison of magnesium determination methods as influenced by soil properties. Agriculture 2010, 97, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen, R. Soil and fertilizer magnesium. Better Crops 2010, 94, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Nazim, H.; Liang, Z.; Yang, D. Magnesium deficiency in plants: An urgent problem. Crop J. 2016, 4, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkesford, M.; Horst, W.; Kichey, T.; Lambers, H.; Schjoerring, J.; Møller, I.S.; White, P. Functions of Macronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Marschner, P., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Pergamon, UK, 2011; pp. 135–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonewille, J.T. Magnesium in dairy cow nutrition: An overview. Plant Soil 2013, 368, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooledge, E.C.; Sturrock, C.J.; Atkinson, B.S.; Mooney, S.J.; Brailsford, F.L.; Murphy, D.V.; Leake, J.R.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Herbal leys have no effect on soil porosity, earthworm abundance, and microbial community composition compared to a grass-clover ley in a sheep grazed grassland after 2-years. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 365, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorczyk, S.; Alberski, J.; Olszewska, M. Accumulation of potassium, calcium and magnesium by selected species of grassland legumes and herbs. J. Elem. 2013, 18, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, J.; Seidel, M.; Kayser, M. Potassium dynamics of four grassland soils contrasting in soil K management history. Grassl. Sci. 2013, 59, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frau, L.J.; Libohova, Z.; Joost, S.; Levasseur, C.; Jeangros, B.; Bragazza, L.; Sinaj, S. Regional investigation of spatial-temporal variability of soil magnesium—A case study from Switzerland. Geoderma Reg. 2020, 21, e00278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB, World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, J.A. Experiments with Mixtures: Designs, Models, and the Analysis of Mixture Data, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeuwijk, L.P. Procedures for Soil Analysis, 6th ed.; Technical Paper No. 9; FAO/ISRIC: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2002; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2020. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Moral, R.A.; Vishwakarma, R.; Connolly, J.; Byrne, L.; Hurley, C.; Finn, J.A.; Brophy, C. Going beyond richness: Modelling the BEF relationship using species identity, evenness, richness and species interactions via the DImodels R package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 2250–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, L.; Connolly, J.; Finn, J.A.; Brophy, C.; Nyfeler, D. Diversity-interaction modeling: Estimating contributions of species identities and interactions to ecosystem function. Ecology 2009, 90, 2032–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.M. Reducing transformation bias in curve fitting. American Statistician 1984, 38, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spychalski, W.; Kosiada, T.; Otremba, K. Content of potassium forms in an anthropogenic soil formed from post-mining lands under diversified agricultural practices. Acta Sci. Pol.—Agric. 2007, 6, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Roscher, C. Linking plant diversity–productivity relationships to plant functional traits of dominant species and changes in soil properties in 15-year-old experimental grasslands. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyfeler, D.; Huguenin-Elie, O.; Suter, M.; Frossard, E.; Connolly, J.; Lüscher, A. Strong mixture effects among four species in fertilized agricultural grassland led to persistent and consistent transgressive overyielding. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öborn, I.; Edwards, A.C.; Hillier, S. Quantifying uptake rate of potassium from soil in a long-term grass rotation experiment. Plant Soil 2010, 335, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailes, K.J.; Aitken, R.L.; Menzies, N.W. Magnesium in tropical and subtropical soils from north-eastern Australia. I. Magnesium fractions and interrelationships with soil properties. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1997, 35, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, M.; Andersson, S.; Andrist-Rangel, Y.; Hillier, S.; Mattsson, L.; Öborn, I. Potassium release and fixation as a function of fertilizer application rate and soil parent material. Geoderma 2007, 198, 140–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Chemical Properties | Unit | PL1 Cambisols Soil | PL2 Luvisols Soil |

|---|---|---|---|

| pHH2O | - | 6.45 | 5.92 |

| pHKCl | - | 5.55 | 5.17 |

| Exchangeable H+ (He+) | cmol(+) kg−1 | 1.85 | 2.15 |

| Total exchangeable base (TEB) | cmol(+) kg−1 | 7.08 | 6.03 |

| Cation-exchange capacity (CEC) | cmol(+) kg−1 | 8.93 | 8.18 |

| Total nitrogen content (N) | % | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Total carbon content (C) | % | 0.59 | 0.68 |

| Phosphorus content (P) | mg∙kg−1 | 57.41 | 32.26 |

| Class of abundance | - | medium | low |

| Soil Chemical Properties | Unit | PL1 Cambisols Soil | PL2 Luvisols Soil |

|---|---|---|---|

| pHH2O | - | 6.34 | 5.67 |

| pHKCl | - | 5.37 | 4.85 |

| Exchangeable H+ (He+) | cmol(+) kg−1 | 2.09 | 2.79 |

| Total exchangeable base (TEB) | cmol(+) kg−1 | 6.05 | 4.08 |

| Cation-exchange capacity (CEC) | cmol(+) kg−1 | 8.14 | 6.87 |

| Total nitrogen content (N) | % | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Total carbon content (C) | % | 0.76 | 1.04 |

| Phosphorus content (P) | mg∙kg−1 | 66.01 | 47.47 |

| Class of abundance | - | high | medium |

| Experiment Stage | Cation | PL1 Cambisols Soil | PL2 Luvisols Soil |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before establishment | Potassium content (K) (mg∙kg−1) | 99.88 | 107.62 |

| Class of abundance | medium | medium | |

| Magnesium content (Mg) (mg∙kg−1) | 14.60 | 14.00 | |

| Class of abundance | very low | very low | |

| After termination | Potassium content (K) (mg∙kg−1) | 91.31 | 84.60 |

| Class of abundance | low | low | |

| Magnesium content (Mg) (mg∙kg−1) | 13.96 | 14.70 | |

| Class of abundance | very low | very low |

| K and Mg Forms | Extractant | Denotation | Description of the Extraction Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2O-soluble | H2O | K-H2O Mg-H2O | 100 g soil + 100 cm3 H2O (1:1) → shake 1.5 h → filter |

| Active | 0.01 mol∙dm−3 CaCl2 | K-CaCl2 Mg-CaCl2 | 2 g soil + 100 cm3 0.01 mol·dm−3 CaCl2 (1:50) → shake 1.5 h → filter |

| Exchangeable | 1 mol∙dm−3 NH4OAc by pH 7.0 | K-CH3COONH4 Mg-CH3COONH4 | 2 g soil + 100 cm3 CH3COONH4 (1:50) → shake 1.5 h → filter |

| Cation | Site No. | Soil Type | Extractant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | CaCl2 | NH4OAc | ||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |||

| K | PL1 | Cambisols | 13.26 | 0.33 | 83.90 | 2.07 | 99.96 | 1.72 |

| PL2 | Luvisols | 37.90 | 3.00 | 119.13 | 5.79 | 138.56 | 5.50 | |

| Mg | PL1 | Cambisols | 2.45 | 0.08 | 104.19 | 3.38 | 113.24 | 3.40 |

| PL2 | Luvisols | 3.86 | 0.23 | 71.90 | 2.58 | 82.15 | 3.27 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orešković, M.; Spychalski, W.; Golińska, B.; Goliński, P. Effects of Grassland Ley Sward Diversity on Soil Potassium and Magnesium Forms in Two Contrasting Sites. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122815

Orešković M, Spychalski W, Golińska B, Goliński P. Effects of Grassland Ley Sward Diversity on Soil Potassium and Magnesium Forms in Two Contrasting Sites. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122815

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrešković, Matej, Waldemar Spychalski, Barbara Golińska, and Piotr Goliński. 2025. "Effects of Grassland Ley Sward Diversity on Soil Potassium and Magnesium Forms in Two Contrasting Sites" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122815

APA StyleOrešković, M., Spychalski, W., Golińska, B., & Goliński, P. (2025). Effects of Grassland Ley Sward Diversity on Soil Potassium and Magnesium Forms in Two Contrasting Sites. Agronomy, 15(12), 2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122815