Effects of Exogenous Hormones on Endophytic Rhizobial Proliferation and Growth Promotion in Alfalfa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Bacterial Strains

2.1.2. Plant Hormones

2.1.3. Plant Materials

2.1.4. Culture Media

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.2.1. Preparation of Exogenous Hormone Solutions at Different Concentrations

2.2.2. Activation of Rhizobium Strains

2.2.3. Determination of the Optimal Hormone Concentration for the Growth of Fluorescently Labeled Rhizobia

2.2.4. Hormone Treatment and Alfalfa Plant Culture

2.2.5. Determination Indexes and Methods

- (1)

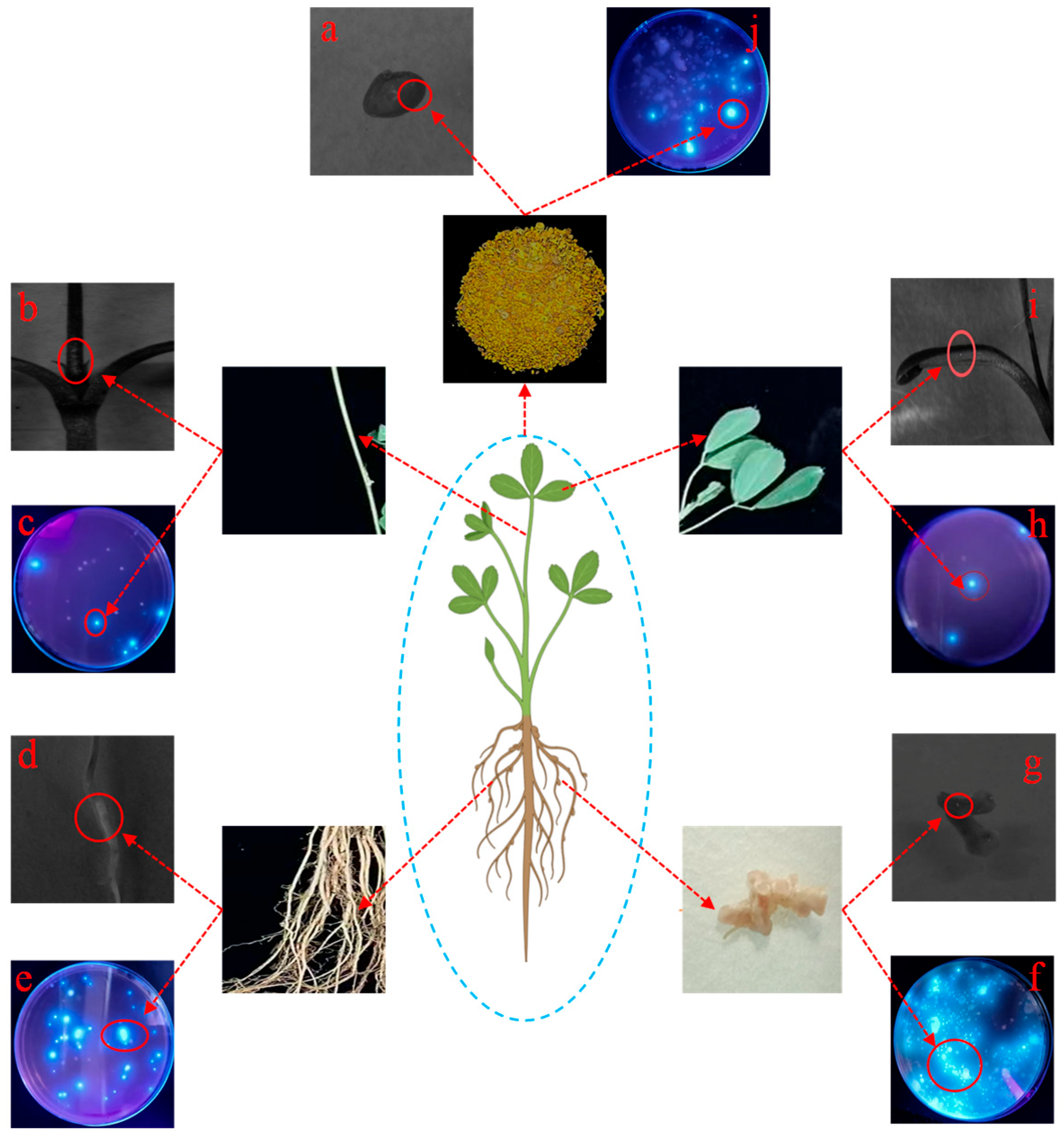

- Method for Detecting Fluorescently Labeled Endophytic Rhizobia

- (2)

- Assessment of Nodulation Traits

- (3)

- Assessment of Nitrogen Fixation Activity

- (4)

- Determination of Plant Biomass

2.3. Statistic Analysis

3. Results

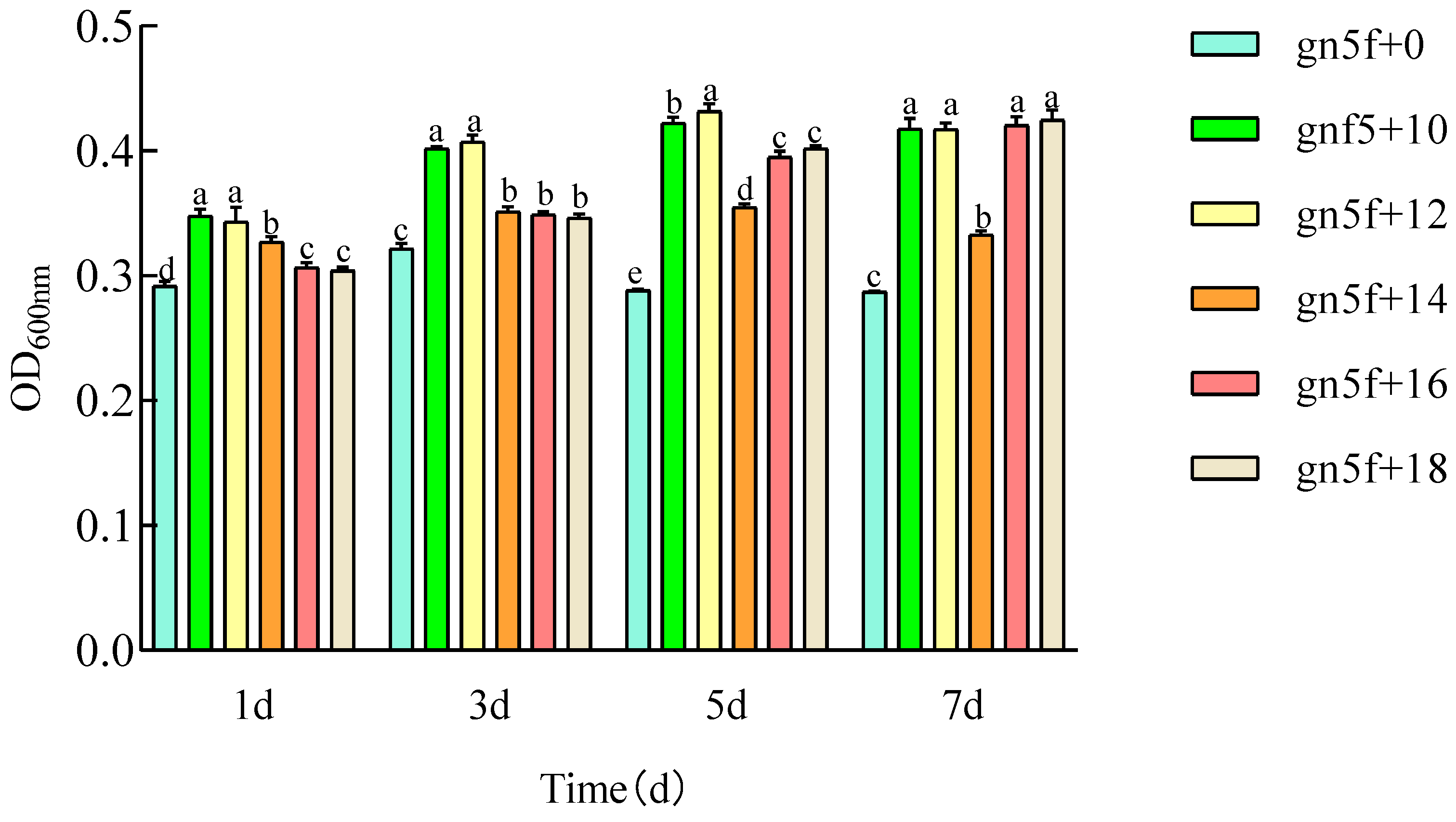

3.1. Effects of Exogenous Hormone Concentrations on the Growth of the Fluorescently Labeled Rhizobium Strain R.gn5f

3.1.1. 3-Indoleacetic Acid

3.1.2. 6-Benzyladenine

3.1.3. Homobrassinolide

3.2. Effects of Exogenous Hormones on the Proliferation of Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f and Seedling Growth During the Vegetative Stage

3.2.1. Effects of Exogenous Hormones During the Vegetative Growth Stage on the Proliferation of Endophytic Rhizobia R.gn5f in Alfalfa

3.2.2. Effects of Exogenous Hormones During the Vegetative Growth Stage on Nodulation and Nitrogen Fixation in Alfalfa Inoculated with Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f

3.2.3. Effects of Exogenous Hormones on Alfalfa Seedling Growth Inoculated with Marked Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f

3.3. Effects of Exogenous Hormones on Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f Proliferation and Plant Growth During the Reproductive Stage

3.3.1. Effects of Exogenous Hormones During the Reproductive Growth Stage on the Proliferation of Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f in Alfalfa

3.3.2. Effects of Exogenous Hormones During the Reproductive Growth Stage on Nodulation and Nitrogen Fixation in Alfalfa Inoculated with Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f

3.3.3. Effects of Exogenous Hormones on the Growth of Alfalfa Plants Inoculated with Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f

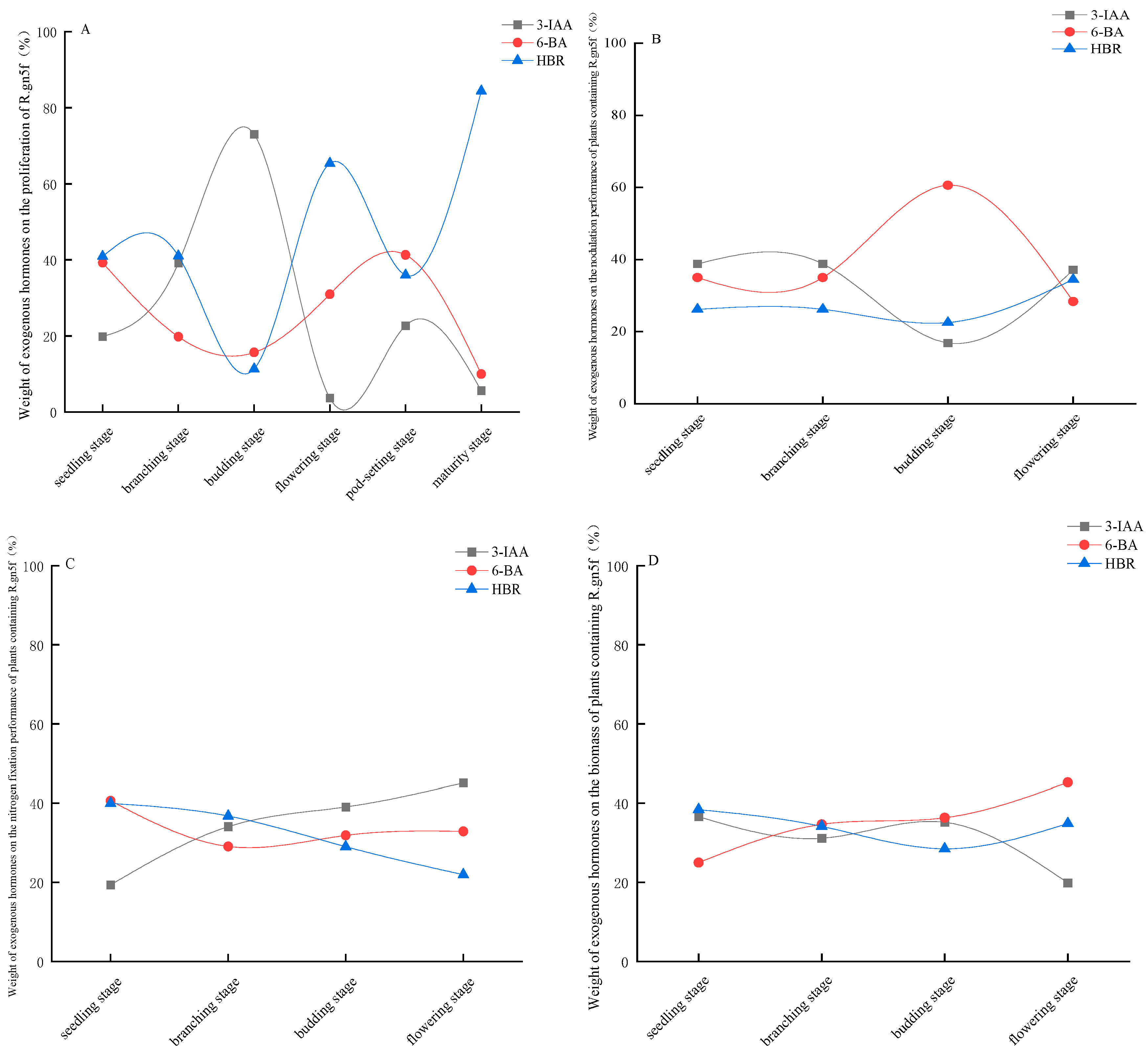

3.4. Contribution of Exogenous Hormones to the Proliferation of Endophytic Rhizobium R.gn5f and the Nitrogen Fixation Performance and Biomass of Alfalfa Plants

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Auxin on the Proliferation of Endophytic Rhizobia and Plant Growth

4.2. Effects of Cytokinin on the Proliferation of Endophytic Rhizobia and Plant Growth

4.3. Effects of Brassinosteroid on the Proliferation of Endophytic Rhizobia and Plant Growth

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y. Development and utilization and biological characteristics of Medicago sativa L. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2007, 35, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.A.; Wu, R.; Selles, F.; Harker, K.N.; Clayton, G.W.; Bittman, S.; Zebarth, B.J.; Lupwayi, N.Z. Crop yield and nitrogen concentration with controlled release urea and split applications of nitrogen as compared to non-coated urea applied at seeding. Field Crops Res. 2012, 127, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.W. Isolation and Characterization of Early Symbiosis Signal Pathway Genes in Soybean. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y. Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation Systems in Plants. China Foreign Med. Treat. 2006, 6, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, B.K.; Lowe, D.J. Mechanism of Molybdenum Nitrogenase. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 2983–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seefeldt, L.C.; Hoffman, B.M.; Dean, D.R. Mechanism of Mo-Dependent Nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 701–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Lin, M.; Ping, S.Z. Biological Nitrogen Fixation and Its Application in Sustainable Agriculture. Biotechnol. Bull. 2008, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.H.; Hu, Y.G. Review on studies on the important role of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in agriculture and livestock production and the factors affecting its efficiency. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2006, 14, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. Biological Nitrogen Fixation and Eco-Agriculture. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2006, 18, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, C.; Yuan, C.; Shan, M.; Fan, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ren, L.; Cui, L.; Wang, C. Effects of Different Intertillage Practices on Soil Biochemical Properties and Soybean Yield in Soybean Fields. Agronomy 2025, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.X. Identification of Alfalfa Rhizobia and Their Correlations with Soil Physical and Chemical Properties. Master’s Thesis, Ningxia University, Yinchuan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, M.Y. Mechanism of Auxin Transport in Salicylic Acid-Induced Immune Response and Soybean Nodulation. Ph.D. Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q. Migration of Rhizobia Inside Alfalfa Plants and Influencing Factors. Ph.D. Thesis, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saikia, S.P.; Srivastava, G.C.; Jain, V. Nodule-Like Structures Induced on the Roots of Maize Seedlings by the Addition of Synthetic Auxin 2, 4-D and Its Effects on Growth and Yield. Cereal Res. Commun. 2004, 32, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, Z.F.; Feng, Y.J.; Wu, C.X. Regulation of Plant Hormones on the Formation and Development of Legumes Root Nodules. Soybean Sci. 2013, 32, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Frank, M.; Reid, D. No Home Without Hormones: How Plant Hormones Control Legume Nodule Organogenesis. Plant Commun. 2020, 1, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandwal, A.S.; Bharti, S. Effect of Kinetin and Indole Acetic Acid on Growth, Yield and Nitrogen Fixing Efficiency of Nodules in Pea (Pisum sativum L.). Indian J. Plant Physiol. 1982, 25, 358–363. [Google Scholar]

- McGuiness, P.N.; Reid, J.B.; Foo, E. The Role of Gibberellins and Brassinosteroids in Nodulation and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Associations. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J. Nodule Development and Self-Regulation in Legume Plants. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2013, 41, 13110–13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.Y. Effects of Exogenous Materials on the Migration and Colonization of Rhizobia in Alfalfa Plants. Ph.D. Thesis, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Shi, S.L.; Kang, W.J.; Miao, Y.Y.; Wu, F. Effects of storage methods on the transmissibility of endophytic rhizobia from alfalfa seeds. Grassl. Turf 2022, 42, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, P.H. Antimicrobial-Resistant Rhizobia Screening and Effect Verification of Undesired Microbe Control in the Prepared Rhizobia Inoculant. Ph.D. Thesis, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.L. Study on Growth-promoting Effect of Robinia pseudoacacia Rhizobia on Platycodon gradiflorus. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2014, 26, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Q.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, B. Effects of Endogenous Hormone Change and Exogenous Auxin on the Germination Process of Alfalfa Seed. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2018, 26, 691–696. [Google Scholar]

- Anuradha, S.; Rao, S.S.R. Effect of brassinosteroids on salinity stress induced inhibition of seed germination and seedling growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2001, 33, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.J. Biotype Classification of Medicago sativa Rhizobia and Its Transcriptome Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Q.; Han, X.Z.; Qiao, Y.F.; Yan, J.; Li, X.H. Effects of low molecular organic acids on nitrogen accumulation, nodulation, and nitrogen fixation of soybean (Glycine max L.) under phosphorus deficiency stress. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 20, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.M.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, F.S. Effects of Improvement of Iron Nutrition by Mixed Cropping with Maize on Nodule Microstructure and Leghaemoglobin Content of Peanut. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2003, 29, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Jin, C.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, M.; Li, D.; Cui, Z.; Wang, S. Expression and Identification of Replication and Transcription-competent Ebola Virus-like Particles. Chin. J. Virol. 2017, 33, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santelia, D.; Henrichs, S.; Vincenzetti, V.; Sauer, M.; Bigler, L.; Klein, M.; Bailly, A.; Lee, Y.; Friml, J.; Geisler, M.; et al. Flavonoids Redirect PIN-Mediated Polar Auxin Fluxes During Root Gravitropic Responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 31218–31226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Auxin Biosynthesis and Its Role in Plant Development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Friml, J. Auxin Regulates Distal Stem Cell Differentiation in Arabidopsis Roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12046–12051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, R.J.; Csukasi, F.; Catalá, C. Mechanisms Regulating Auxin Action During Fruit Development. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 151, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Huang, Y.; Qi, P.; Lian, G.; Hu, X.; Han, N.; Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Qian, Q.; Bian, H. Functional Analysis of Auxin Receptor Ostir1/Osafb Family Members in Rice Grain Yield, Tillering, Plant Height, Root System, Germination, and Auxinic Herbicide Resistance. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2676–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigge, M.J.; Platre, M.; Kadakia, N.; Zhang, Y.; Greenham, K.; Szutu, W.; Pandey, B.K.; Bhosale, R.A.; Bennett, M.J.; Busch, W.; et al. Genetic Analysis of the Arabidopsis TIR1/AFB Auxin Receptors Reveals Both Overlapping and Specialized Functions. eLife 2020, 9, e54740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Guo, X.; Zhang, A. Research Advances in Auxin Biosynthesis. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2012, 47, 292–301. [Google Scholar]

- Fässler, E.; Evangelou, M.W.; Robinson, B.H.; Schulin, R. Effects of Indole-3-Acetic Acid(IAA)on Sunflower Growth and Heavy Metal Uptake in Combination with Ethylene Diamine Disuccinic Acid(EDDS). Chemosphere 2010, 80, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teale, W.D.; Paponov, I.A.; Palme, K. Auxin in action: Signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velandia, K.; Reid, J.B.; Foo, E. Right Time, Right Place: The Dynamic Role of Hormones in Rhizobial Infection and Nodulation of Legumes. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, C.W.; Li, X.; Tian, C.F.; Xie, F.; Cao, Y.R.; Wang, E.T. Advances in the legume–rhizobia symbiosis. Plant Physiol. J. 2023, 59, 1407–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope-Selby, N.; Cookson, A.; Squance, M.; Donnison, I.; Flavell, R.; Farrar, K. Endophytic Bacteria in Miscanthus Seed: Implications for Germination, Vertical Inheritance of Endophytes, Plant Evolution and Breeding. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Clcbment, C.; Sessitsch, A. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria in the Rhizo- And Endosphere of Plants: Their Role, Colonization, Mechanisms Involved and Prospects for Utilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benková, E.; Michniewicz, M.; Sauer, M.; Teichmann, T.; Seifertová, D.; Jürgens, G.; Friml, J. Local, Efflux-Dependent Auxin Gradients as a Common Module for Plant Organ Formation. Cell 2003, 115, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pii, Y.; Crimi, M.; Cremonese, G.; Spena, A.; Pandolfini, T. Auxin and Nitric Oxide Control Indeterminate Nodule Formation. BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.J.; Mathesius, U. Phytohormone Regulation of Legume-Rhizobia Interactions. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 40, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.J.; Huang, P.; Zhou, X.; Ran, M. Good Helper for Plant Growth: Cytokinins. Chin. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.B.; Zhang, G.H.; Wang, G.D. Progress on Cytokinin Signaling in Plant Vascular Development. Plant Physiol. J. 2015, 51, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.L.; Gu, W.Y.; Qin, Y.L.; Lv, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.X. Effects of exogenous CTK on the growth and character of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Pratacult. Sci. 2005, 22, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.Y.; Zhou, L.F.; Shi, X.Y.; Wang, M.D.; Zhang, T.J.; Chao, Y.H.; Zhao, Y. Self-activation Detection and Expression Analysis of Cytokinin Response Regulator ARR9 of Medicago truncatula. Chin. J. Grassl. 2021, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Transcriptional Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes Involved in Selective Nodulation in Bradyrhizobium diazoeficiens at the Presence of Soybean Root Exudates. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mens, C.; Li, D.; Haaima, L.E.; Gresshoff, P.M.; Ferguson, B.J. Local and Systemic Effect of Cytokinins on Soybean Nodulation and Regulation of Their Isopentenyl Transferase (IPT) Biosynthesis Genes Following Rhizobia Inoculation. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, M.; Tong, M.; Wu, D.; Chu, J.; Yao, X. Sucrose and Brassinolide Alleviated Nitrite Accumulation, Oxidative Stress and the Reduction of Phytochemicals in Kale Sprouts Stored at Low Temperature. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 208, 112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.A.; Abdullah, B. Effect of Brassinolide Levels on Some Growth of Sunflower Hellanthus annuus L. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 761, 012084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.J.; Lin, M.H.; Gresshoff, P.M. Regulation of Legume Nodulation by Acidic Growth Conditions. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e23426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, M.; Nagaraja, A.; Srivastav, M.; Meena, N.K.; Kumar, M.S.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, R.R. Pleiotropic Influences of Brassinosteroids on Fruit Crops: A Review. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 87, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Ma, D.M.; Zhao, L.J.; Ma, Q.L. Effects of 2,4-table Brassinolide on Enzyme Activity and Root ion Distribution and Absorption in Alfalfa Seedlings. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2021, 29, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhini, B.V.; Rao, S.S.R. Effect of Brassionosteriods on Nodulation and Nitrogenase Activity in Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Growth Regul. 1999, 28, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, Y.-Y.; Kang, W.-J.; Shi, S.-L.; Han, Y.-L.; Guan, J.; Lu, B.-F.; Wu, B. Effects of Exogenous Hormones on Endophytic Rhizobial Proliferation and Growth Promotion in Alfalfa. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122799

Du Y-Y, Kang W-J, Shi S-L, Han Y-L, Guan J, Lu B-F, Wu B. Effects of Exogenous Hormones on Endophytic Rhizobial Proliferation and Growth Promotion in Alfalfa. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122799

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Yuan-Yuan, Wen-Juan Kang, Shang-Li Shi, Yi-Lin Han, Jian Guan, Bao-Fu Lu, and Bei Wu. 2025. "Effects of Exogenous Hormones on Endophytic Rhizobial Proliferation and Growth Promotion in Alfalfa" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122799

APA StyleDu, Y.-Y., Kang, W.-J., Shi, S.-L., Han, Y.-L., Guan, J., Lu, B.-F., & Wu, B. (2025). Effects of Exogenous Hormones on Endophytic Rhizobial Proliferation and Growth Promotion in Alfalfa. Agronomy, 15(12), 2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122799