Transcriptomic Dynamics Associated with the Seed Germination Process of the Invasive Weed Cenchrus longispinus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plants Materials and Seed Germination

2.2. RNA Extraction, cDNA Library Construction, and Sequencing

2.3. Data Quality Control, Assembly, and Annotation

2.4. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

2.5. Verification of the Expression of Key Genes Using RT-qPCR

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Seed Morphology During Germination

3.2. Transcriptomics of C. longispinus M-Type Seeds During Germination

3.2.1. Transcriptome Sequencing Assembly and Correlation Analysis

3.2.2. DEGs Associated with Germination in C. longispinus M-Type Seeds

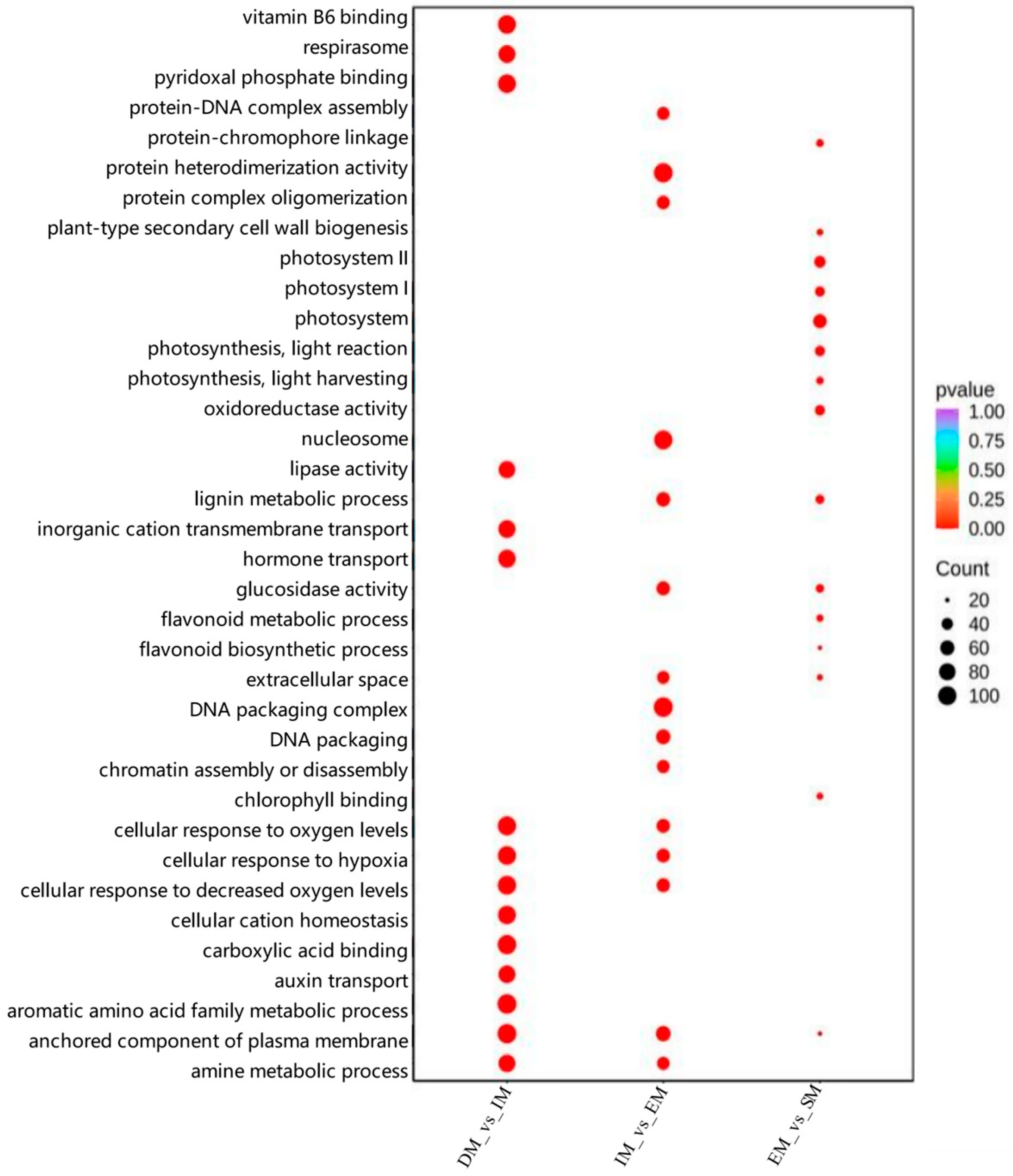

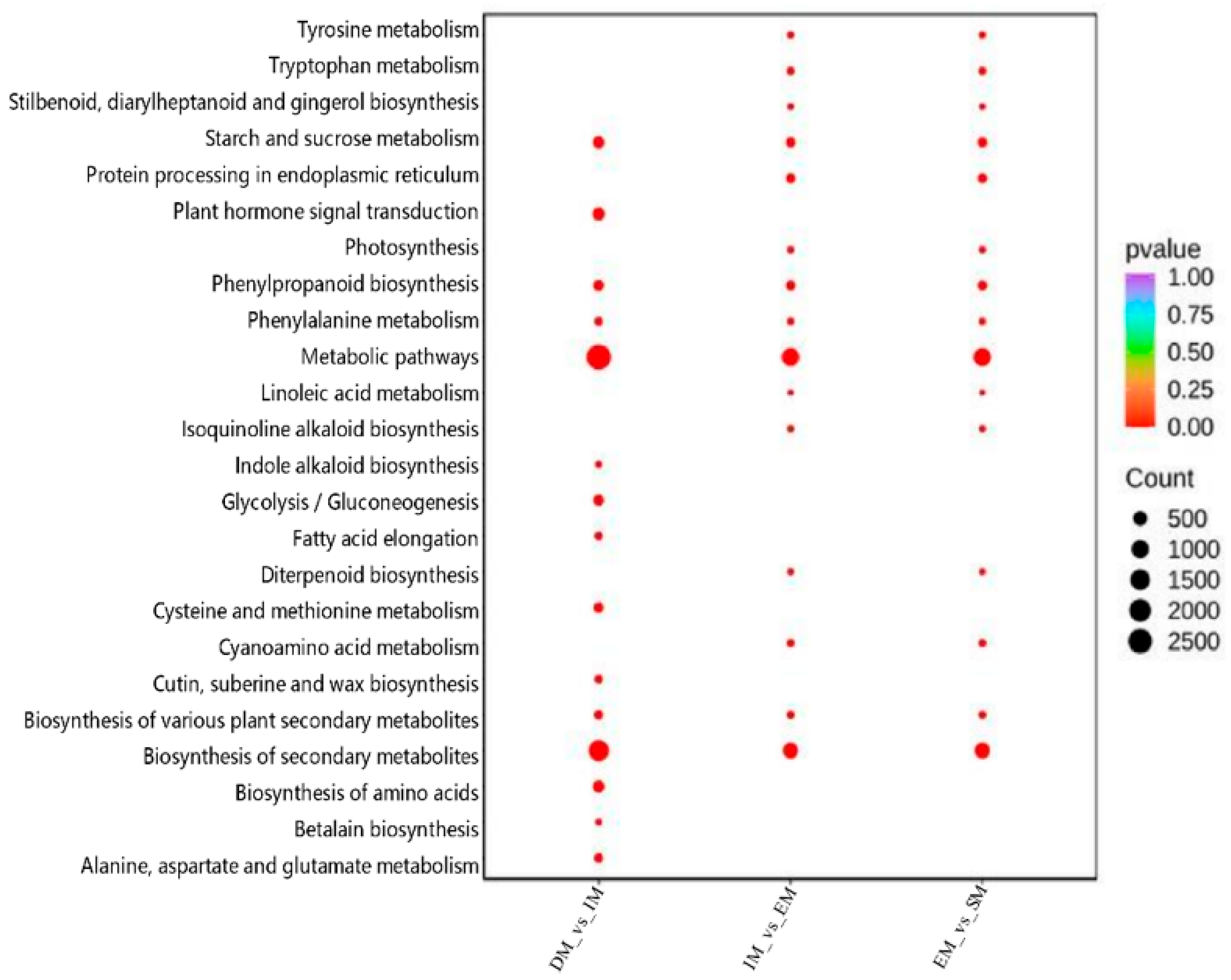

3.3. Dynamic Changes in the Transcriptome During M-Type Seed Germination and GO and KEGG Enrichment Analyses

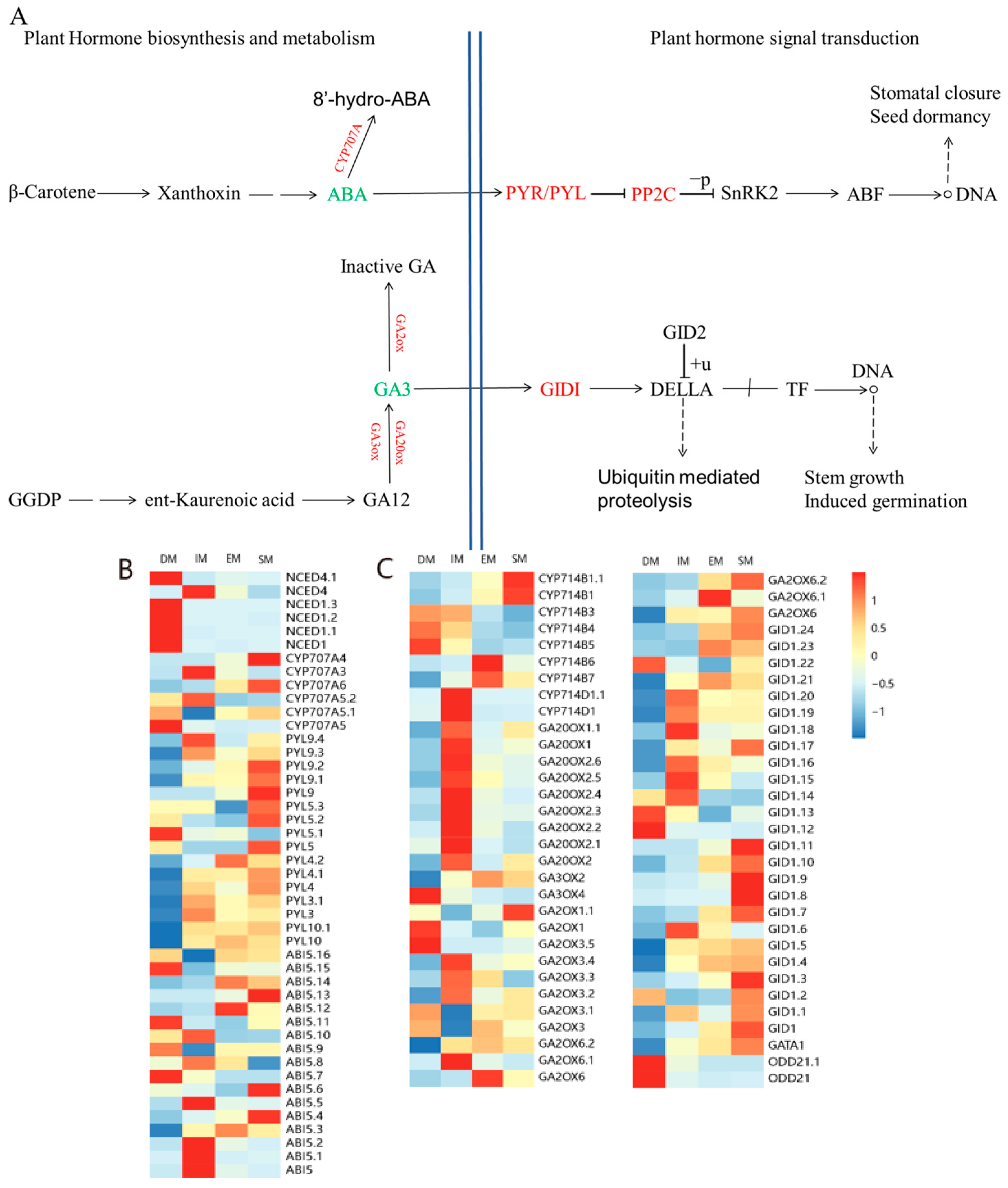

3.4. DEGs Involved in Plant Hormone Signaling Pathways Related to Seed Germination

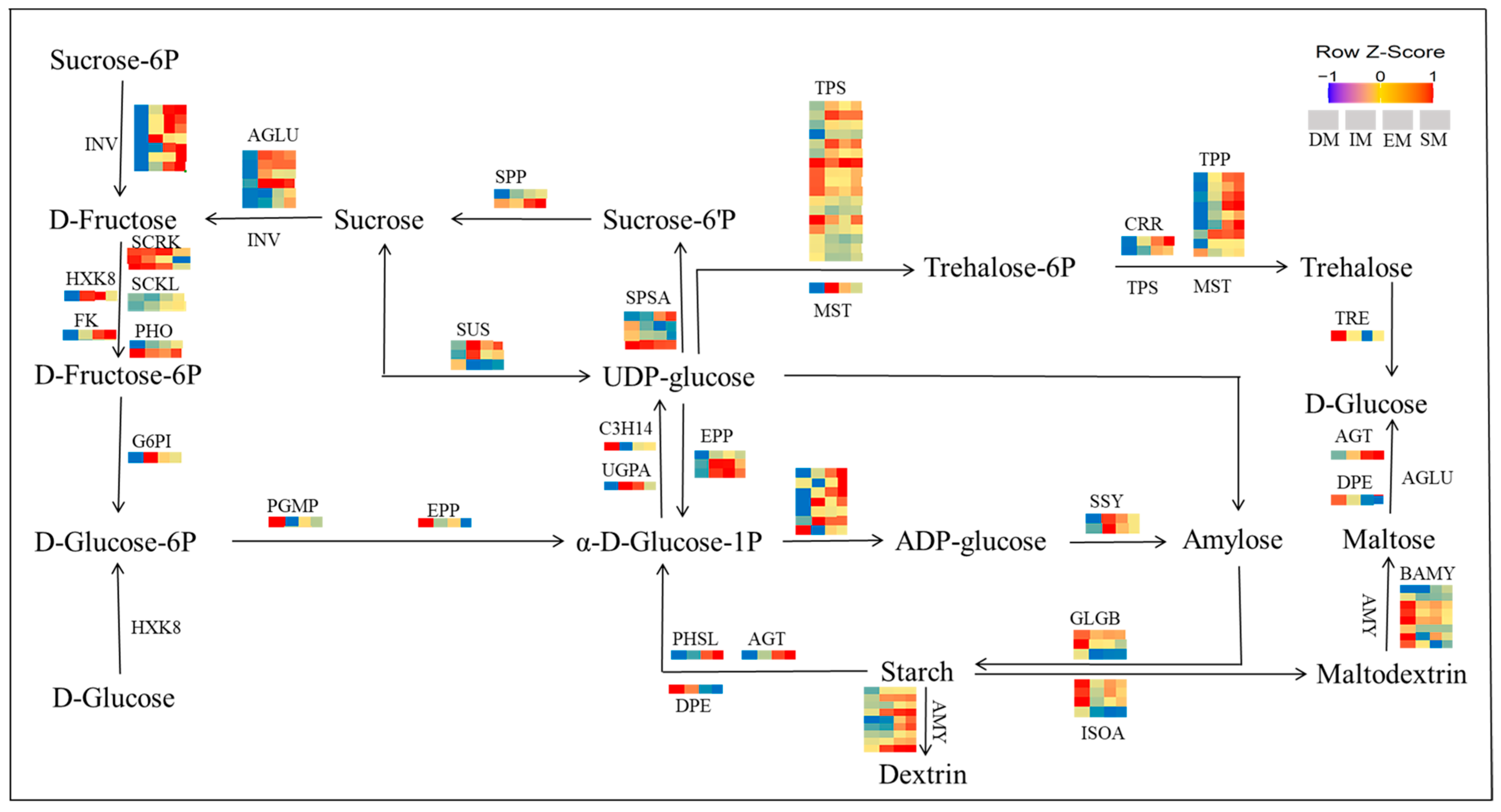

3.5. Starch and Sucrose-Associated Metabolic Pathways Involved in Seed Germination

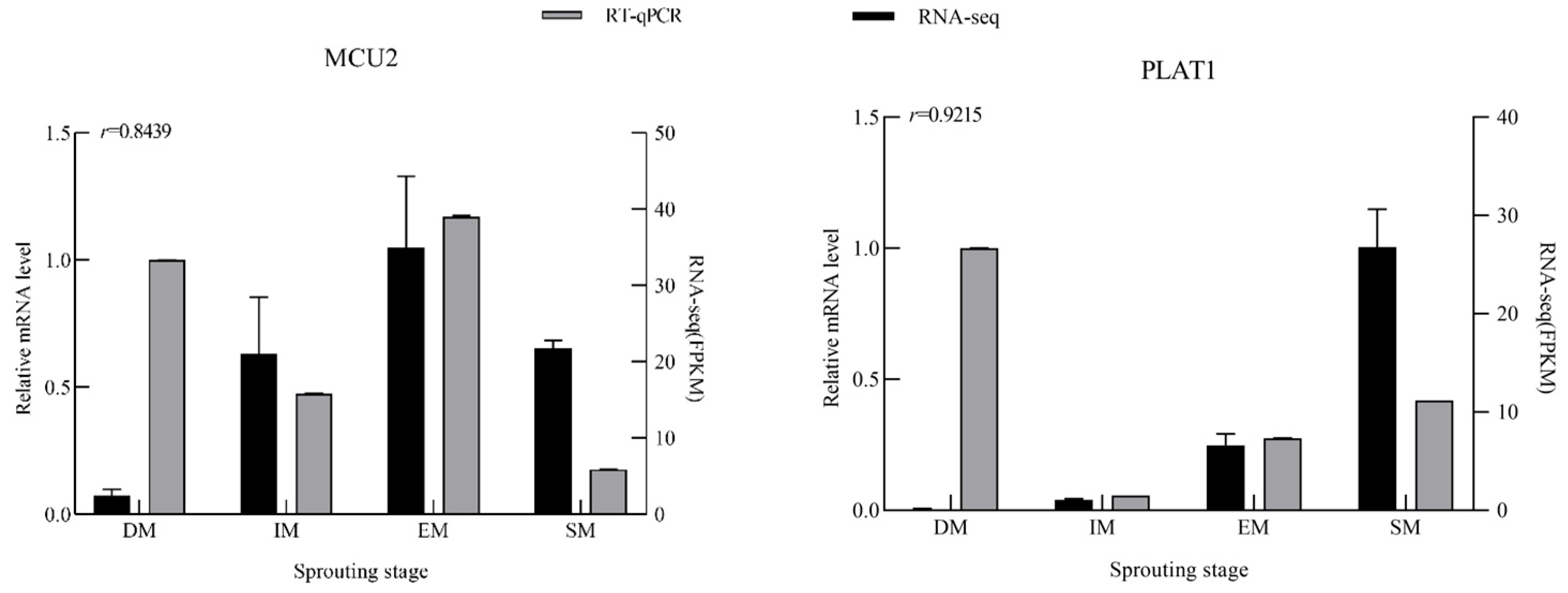

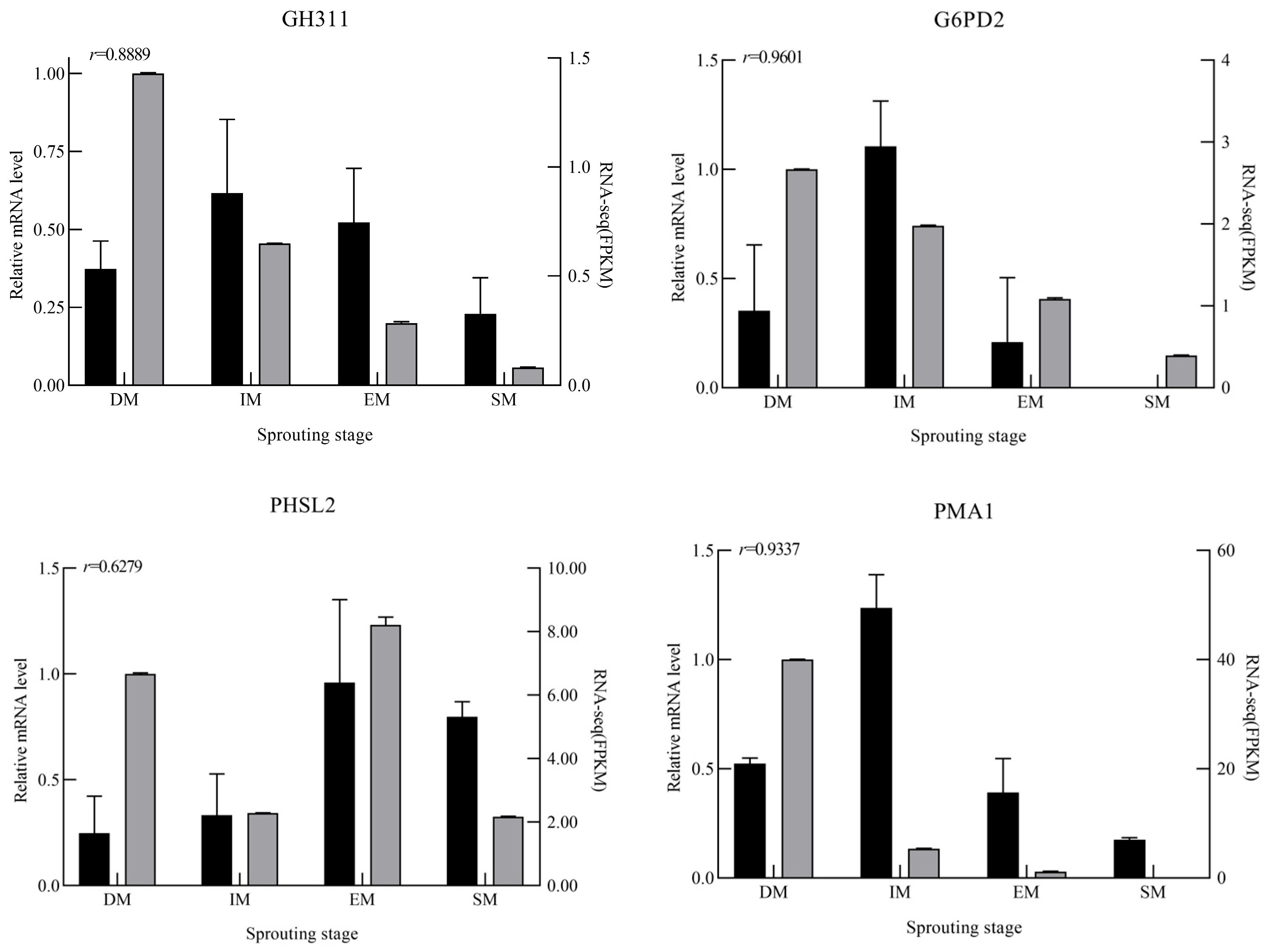

3.6. Analysis of DEGs by RT-qPCR

4. Discussion

4.1. Transcriptomes Dynamics Changed During the Germination of C. longispinus M-Type Seeds

4.2. Starch and Sucrose-Associated Metabolic Pathways Involved in Seed Germination

4.3. DEGs Involved in Plant Hormone Signaling Pathways Related to Seed Germination

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, G.M.; Cao, F.Q.; Liu, W.B.; Hao, F.G. Cenchrus pauciflorus and its damage in grassland of Liaoning Province. Grassl. China 1995, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.L.; Wang, Z.W.; Qi, F.L.; Yang, D.Z.; Men, H.Y.; Sun, B.; Qi, N.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.C. Biological and ecological characteristics of Cenchrus pauciflorus and the integrated control strategies. J. Ecol. 2021, 40, 2593–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Y.; Xie, Y. Invasive Alien Species in China; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H.; Fu, J.W.; Wang, Y.F.; Luo, J.; Yao, Y.; Yang, B.; Shao, R.J.; Zhang, L. Occurrence monitoring and control of Cenchrus pauciflorus in Inner Mongolia. J. Plant Prot. 2021, 41, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.X. Study on the Biological Characteristics of Cenchrus calyculatus Cav. Bachelor’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.Y.; Li, J.H.; Ma, F.; Liu, H.Y. Study on seed germination characteristics of Cenchrus pauciflorus Benth. J. Inn. Mong. Univ. Natl. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 28, 203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, T.; Zhou, L.Y. Heteromorphic seed germination strategy and seedling growth characteristics of invasive plant Cenchrus pauciflorus. Pratac. J. 2022, 31, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Stoian-Dod, R.L.; Dan, C.; Morar, I.M.; Sestras, A.F.; Truta, A.M.; Roman, G.; Sestras, R.E. Seed germination within genus rosa: The complexity of the process and influencing factors. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; He, R.; Tang, X.; Li, M.; Yi, T. RNA-Sequencing analysis reveals critical roles of hormone metabolism and signaling transduction in seed germination of Andrographis paniculata. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, K.A.; Narsai, R.; Carroll, A.; Ivanova, A.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B.; Millar, A.H.; Whelan, J. Mapping metabolic and transcript temporal switches during germination in rice highlights specific transcription factors and the role of RNA instability in the germination process. Plant Physiol. 2008, 149, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, T.; He, Z.L.; Tan, X.Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, X.; Luo, Y.F.; Hu, S.N. An integrated RNA-Seq and network study reveals a complex regulation process of rice embryo during seed germination. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 464, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.L.; Tian, T.; Chen, J.Z.; Wang, D.; Tong, B.L.; Liu, J.M. Transcriptome analysis of Cinnamomum migao seed germination in medicinal plants of southwest China. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.S. Seed Germination and Differential Expression of Related Enes in Different Abutilon theophrasti Populations. Bachelor’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Strgulc Krajšek, S.; Kladnik, A.; Skočir, S.; Bačič, M. Seed germination of invasive Phytolacca americana and potentially invasive P. acinosa. Plants 2023, 12, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, R.H.; Fu, W.D.; Song, Z.; Ni, H.W.; Zhang, G.L. Effects of different cultivation practices on the amount of seeds in the soils and seed production of Cenchrus pauciflorus Benth. J. Agric. Res. Environ. 2015, 32, 312–320. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Chen, Y.D. Seed bank and seed vigor structure characteristics of Cenchrus pauciflorus in different regions of Horqin sandy land. Chin. J. Grassl. 2015, 37, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- International Rules for Seed Testing. Available online: https://www.seedtest.org/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.M.; Oshlack, A. Corset: Enabling differential gene expression analysis for de novo assembled transcriptomes. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 410. [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink, B.; Chao, X.; Huson, D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.Y.; Dillies, M.A. SARTools: A DESeq2- and EdgeR-based rpipeline for comprehensive differential analysis of RNA-seq data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, W.D.; Wang, P.; Zhang, R.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Song, Z.; Xia, G.X.; Wu, J.H. iTRAQ protein profile differential analysis of dormant and germinated grassbur twin seeds reveals that ribosomal synthesis and carbohydrate metabolism promote germination possibly through the PI3K pathway. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derek, B.J.; Bradrord, J.J.; Hihorst, H.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seed: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mccormac, A.C.; Keefe, P.D. Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L.) seed vigour:imbibition effects. J. Exp. Bot. 1990, 7, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitbrecht, K.; Mueller, K.; Leubner-Metzger, G. First off the mark: Early seed germination. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 3289–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, S.R.; Chrobok, D.; Juvany, M.; Delhomme, N.; Lindén, P.; Brouwer, B.; Ahad, A.; Moritz, T.; Jansson, S.; Gardeström, P.; et al. Darkened leaves use different metabolic strategies for senescence and survival. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasulu, N.; Usadel, B.; Winter, A.; Radchuk, V.; Scholz, U.; Stein, N.; Weschkr, W.; Strickert, M.; Close, T.J.; Stitt, M.; et al. Barley grain maturation and germination: Metabolic pathway and regulatory network commonalities and differences highlighted by new MapMan/PageMan profiling tools. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1738–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.; Smith, D.L. Plant hormones and seed germination. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 99, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, K.; Nakabayashi, K.; Miatton, E.; Leubner-Metzger, G.; Soppe, W.J. Molecular mechanisms of seed dormancy. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1769–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Liu, X.D.; Xie, Q.; He, Z.H. Two faces of one seed: Hormonal regulation of dormancy and germination. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.L.; Yan, L.H.; Yan, Y.J.; Chen, W.B. Study on seed morphological structure and seed germination of Sinocalycanthus chinensis. Seed 2021, 40, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, E.J.H. The Seeds of Dicotyledons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1976; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.Z.; Yao, Z.Q.; Cao, X.L.; Peng, J.F.; Xu, Y.; Chen, M.X.; Zhao, S.F. Transcriptome analysis of Phelipanche aegyptiaca seed germination mechanisms stimulated by fluridone, TIS108, and GR24. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e187539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, R.; Siva, R. Analysis of phylogenetic and functional diverge in plant nine-cis epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene family. J. Plant Res. 2015, 128, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todoroki, Y.; Ueno, K. Development of specific inhibitors of CYP707A, a key enzyme in the catabolism of abscisic acid. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 3230–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhang, F.; Luo, X.; Xie, J. Histone deacetylase HDA19 interacts with histone methyltransferase SUVH5 to regulate seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Fan, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, L.; Zhang, C.; Sun, W.; He, H.; Yu, S. OsGRETCHENHAGEN3-2 modulates rice seed storability via accumulation of abscisic acid and protective substances. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, D.; He, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Tian, S.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X. Understanding of hormonal regulation in rice seed germination. Life 2022, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voegele, A.; Linkies, A.; Müller, K.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Members of the gibberellin receptor gene family GID1 (GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1) play distinct roles during Lepidium sativum and Arabidopsis thaliana seed germination. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5131–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Gene ID | Primer Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GH311 | Cluster-73386.4 | F: 5′-AATAGCGTCACTCGTGCCAA-3′ | R: 5′-CGCGTCAATAGGTGTTGCAT-3′ |

| G6PD2 | Cluster77460.1 | F: 5′-TGCGTTCCATGAAGCCGTTG-3′ | R: 5′-ACTATCCTTGGGAACTGTCTGG-3′ |

| MCU2 | Cluster-73819.0 | F: 5′-GCAGAAGGCAGACATCGACC-3′ | R: 5′-GTAGCCGGCCATGAAGTACA-3′ |

| PLAT1 | Cluster-77858.1 | F: 5′-GGAGGACAAGTGCGTGTACA-3′ | R: 5′-TGAAGATGTCGAGGTTGCCC-3′ |

| PMA1 | Cluster-56206.2 | F: 5′- CCGGTGTATTGATCGTCCTTGT-3′ | R: 5′-AGGTACACGGCAGAGGCTA-3′ |

| PHSL | Cluster-65501.3 | F: 5′-ATCCTCAACACAGCTGGCTC-3′ | R: 5′-AGGAAAGGATGACAGGCTTGA-3′ |

| EF1F (Reference) | LOC_Os03g08010 | F: 5′-GTGCTCATTGGCCATGTCGAC-3′ | R: 5′-CCTTGTACCAGTCAAGGTTGG-3′ |

| Sample | Clean Reads | Clean Bases (Gb) | Q30 (%) | GC Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM01 | 57,427,274 | 8.61 | 93.99 | 60.92 |

| DM02 | 67,936,678 | 10.19 | 94.59 | 59.44 |

| DM03 | 59,877,842 | 8.98 | 94.52 | 59.83 |

| IM01 | 67,624,928 | 10.14 | 94.83 | 54.68 |

| IM02 | 60,568,370 | 9.09 | 94.85 | 55.39 |

| IM03 | 51,387,084 | 7.71 | 95.01 | 55.3 |

| EM01 | 51,180,072 | 7.68 | 96.13 | 54.5 |

| EM02 | 76,538,254 | 11.48 | 93.39 | 55.74 |

| EM03 | 57,874,496 | 8.68 | 95.01 | 56.05 |

| SM01 | 54,008,910 | 8.1 | 94.48 | 56.08 |

| SM02 | 57,269,048 | 8.59 | 94.41 | 56.72 |

| SM03 | 58,710,964 | 8.81 | 94.6 | 55.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.-Y.; Li, Y.-Y.; Guo, L.-Z.; Bao, H.; Lin, K.-J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, R.; Hao, L.-F. Transcriptomic Dynamics Associated with the Seed Germination Process of the Invasive Weed Cenchrus longispinus. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122789

Xu X-Y, Li Y-Y, Guo L-Z, Bao H, Lin K-J, Ji Y, Wang R, Hao L-F. Transcriptomic Dynamics Associated with the Seed Germination Process of the Invasive Weed Cenchrus longispinus. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122789

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiao-Yang, Yu-Yu Li, Li-Zhu Guo, Han Bao, Ke-Jian Lin, Yu Ji, Rui Wang, and Li-Fen Hao. 2025. "Transcriptomic Dynamics Associated with the Seed Germination Process of the Invasive Weed Cenchrus longispinus" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122789

APA StyleXu, X.-Y., Li, Y.-Y., Guo, L.-Z., Bao, H., Lin, K.-J., Ji, Y., Wang, R., & Hao, L.-F. (2025). Transcriptomic Dynamics Associated with the Seed Germination Process of the Invasive Weed Cenchrus longispinus. Agronomy, 15(12), 2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122789