Interpreting Machine Learning Models with SHAP Values: Application to Crude Protein Prediction in Tamani Grass Pastures

Abstract

1. Introduction

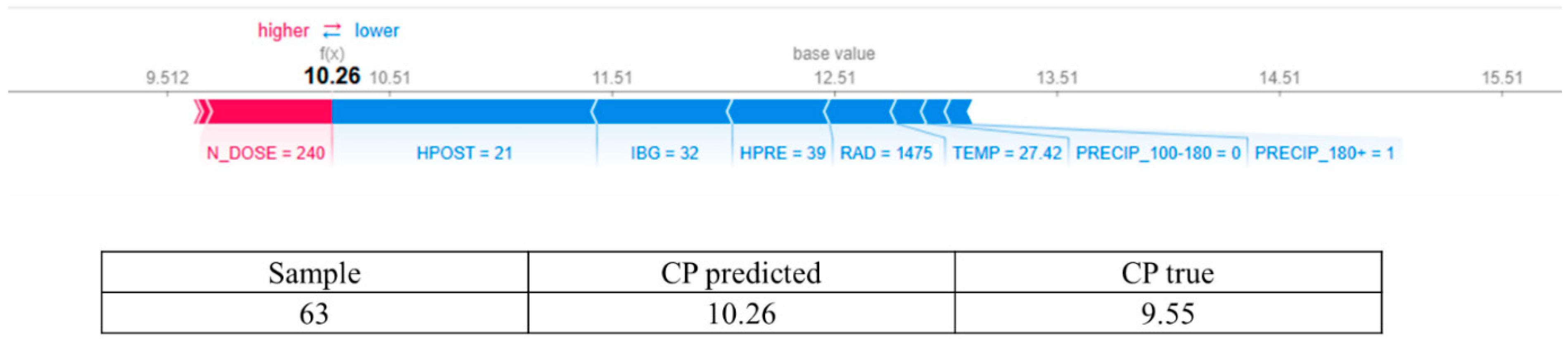

- It provides an interpretation of the XGBoost model for predicting the crude protein (CP) content of Tamani grass leaves using the SHAP technique. This represents an advance in the methodological framework for forage production studies, offering an explainable model that generates insights to support decision-making.

- The analysis revealed that rainfall within the range of 100–180 mm tends to increase the CP content of Tamani grass leaves, underscoring the value of interpretability in identifying optimal management practices.

- The findings demonstrated that the application of 240 kg ha−1 year−1 of nitrogen enhances leaf CP content when combined with favorable pasture structural conditions, such as appropriate pre- and post-grazing heights.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Description

2.2. Machine Learning

2.3. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)

3. Results

- RQ1: When disregarding the effect of the season, does the order of the variables with the greatest impact change?

- RQ2: How does increasing nitrogen dose (N_DOSE) affect CP content?

- RQ3: Which precipitation range has positive SHAP values in predicting the CP content of tamani grass?

- RQ4: Does N_DOSE influence the hierarchy of importance of management and environmental variables in predicting the CP content of tamani grass leaves?

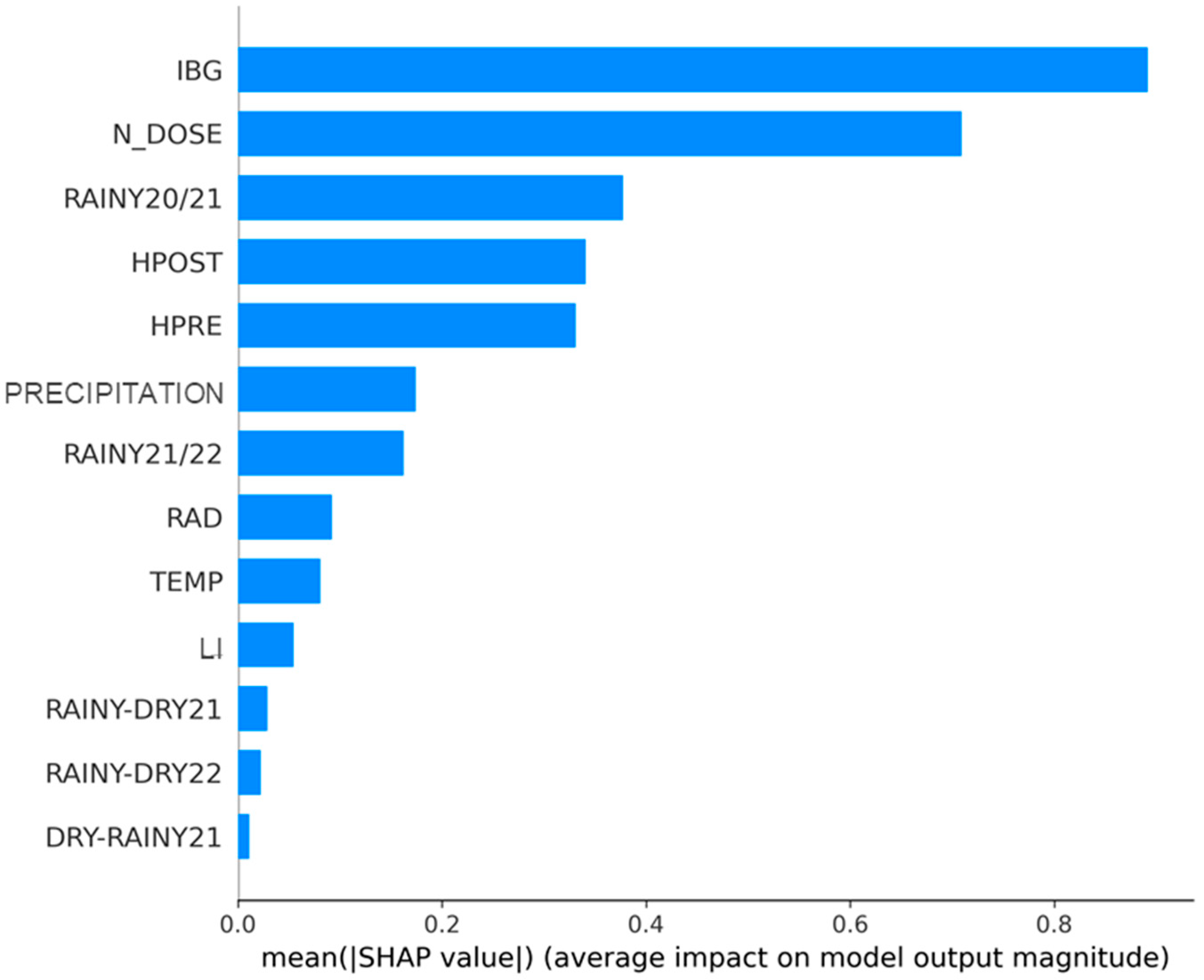

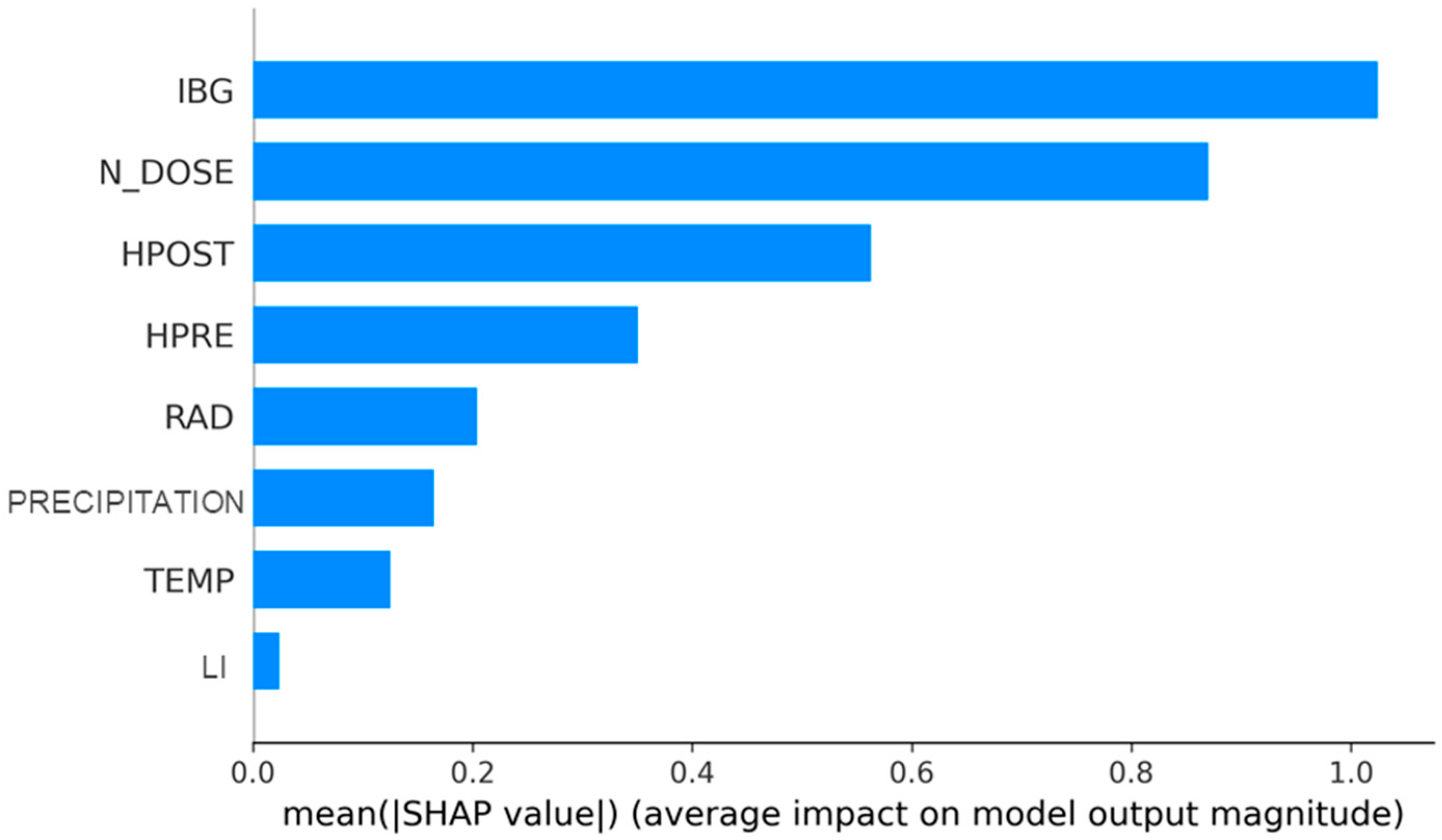

3.1. Answering RQ1: When the Effect of the Season Is Disregarded, Is There a Change in the Order of the Variables That Have the Greatest Impact?

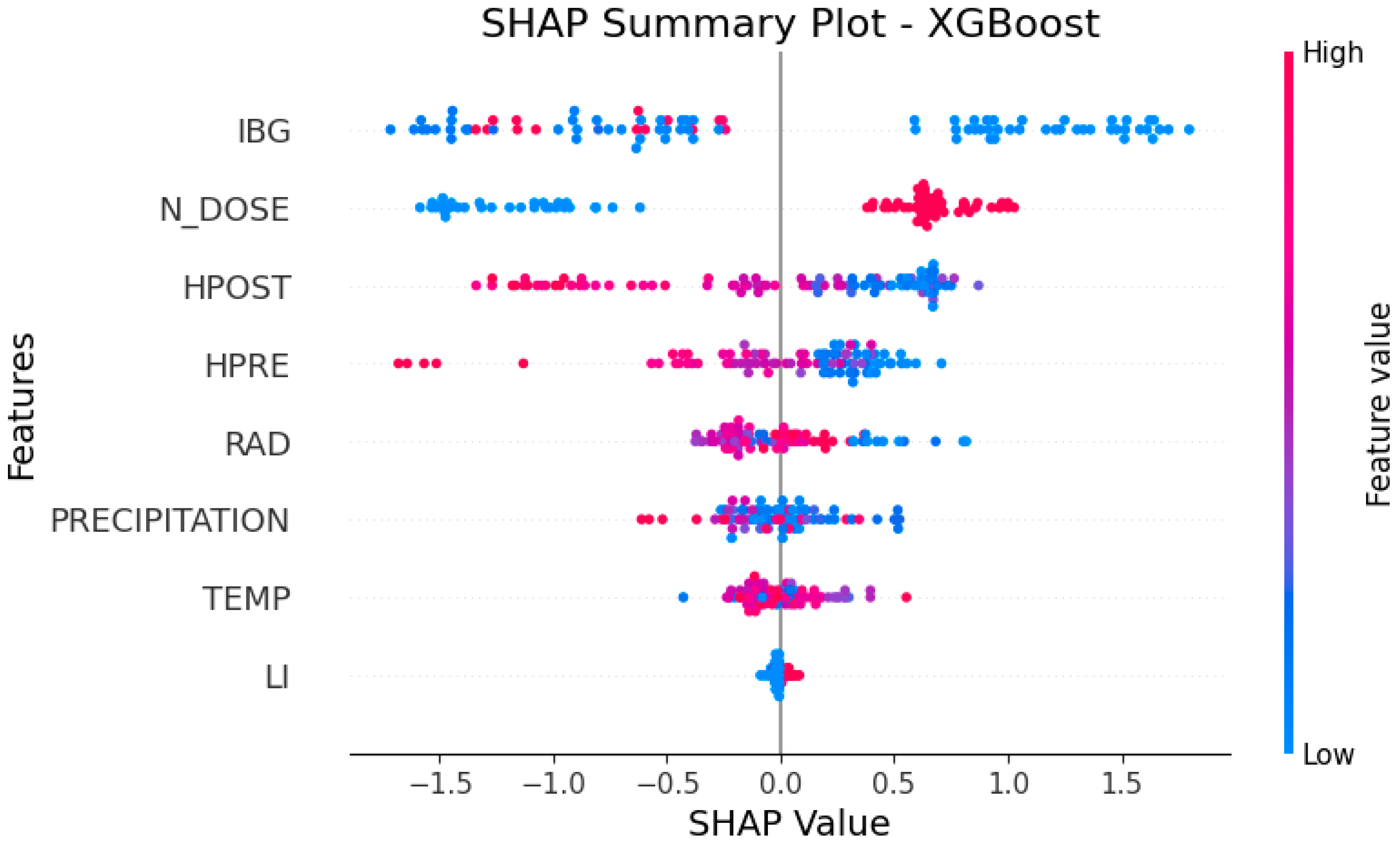

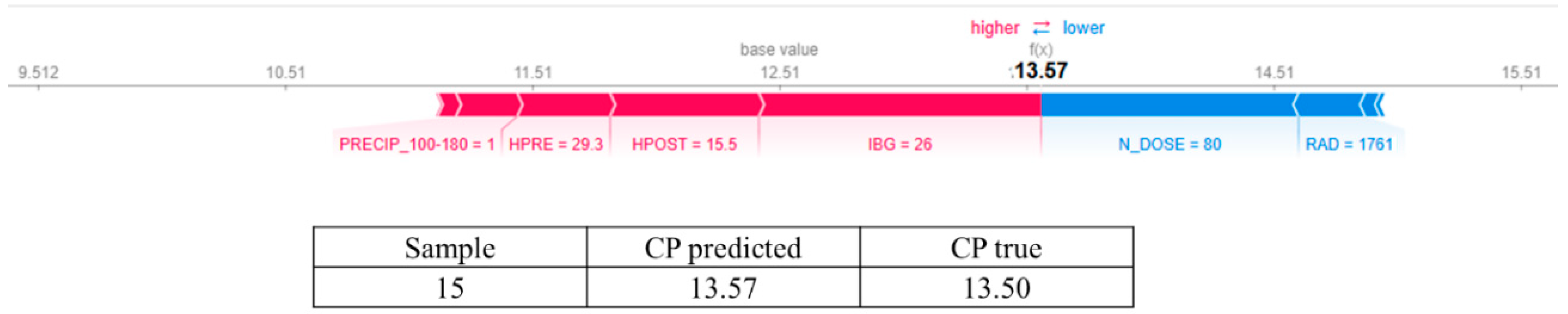

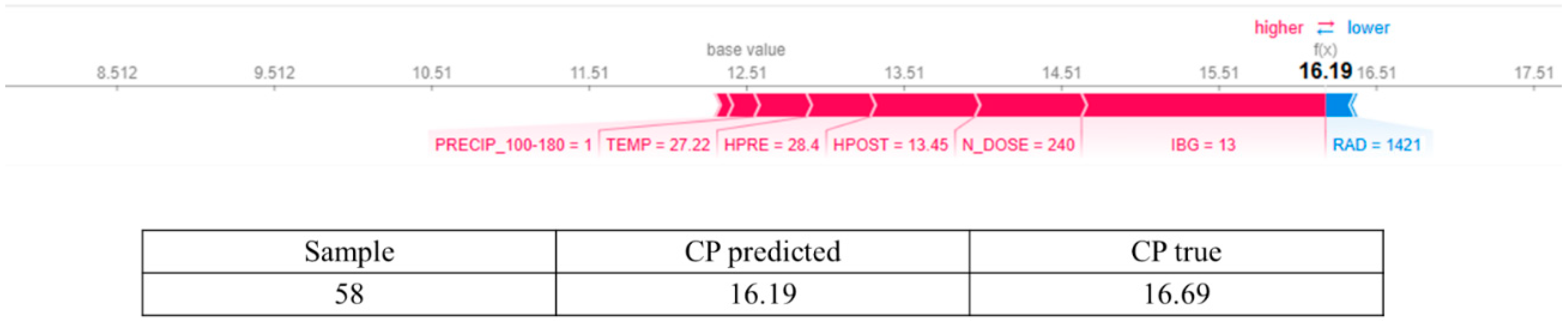

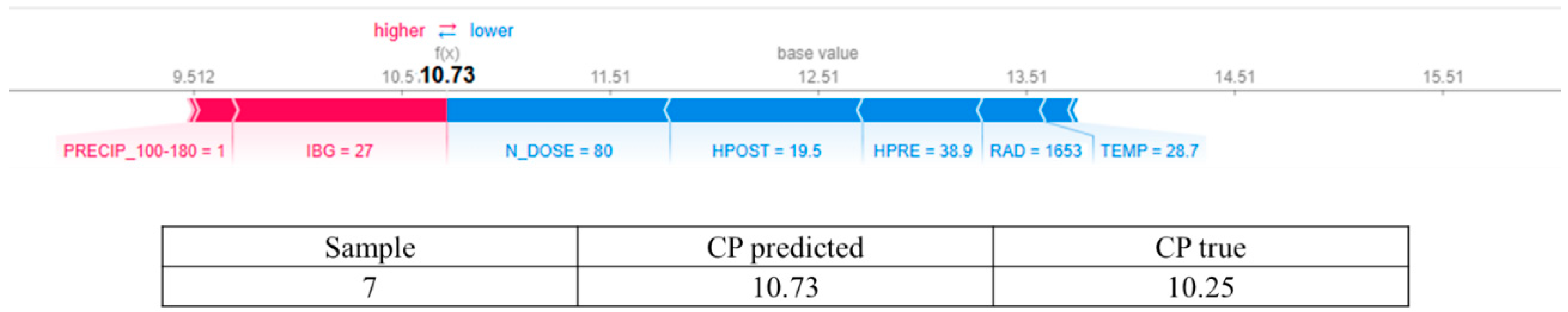

3.2. Answering RQ2: How Does Increasing Nitrogen Dose (N_DOSE) Affect CP Content?

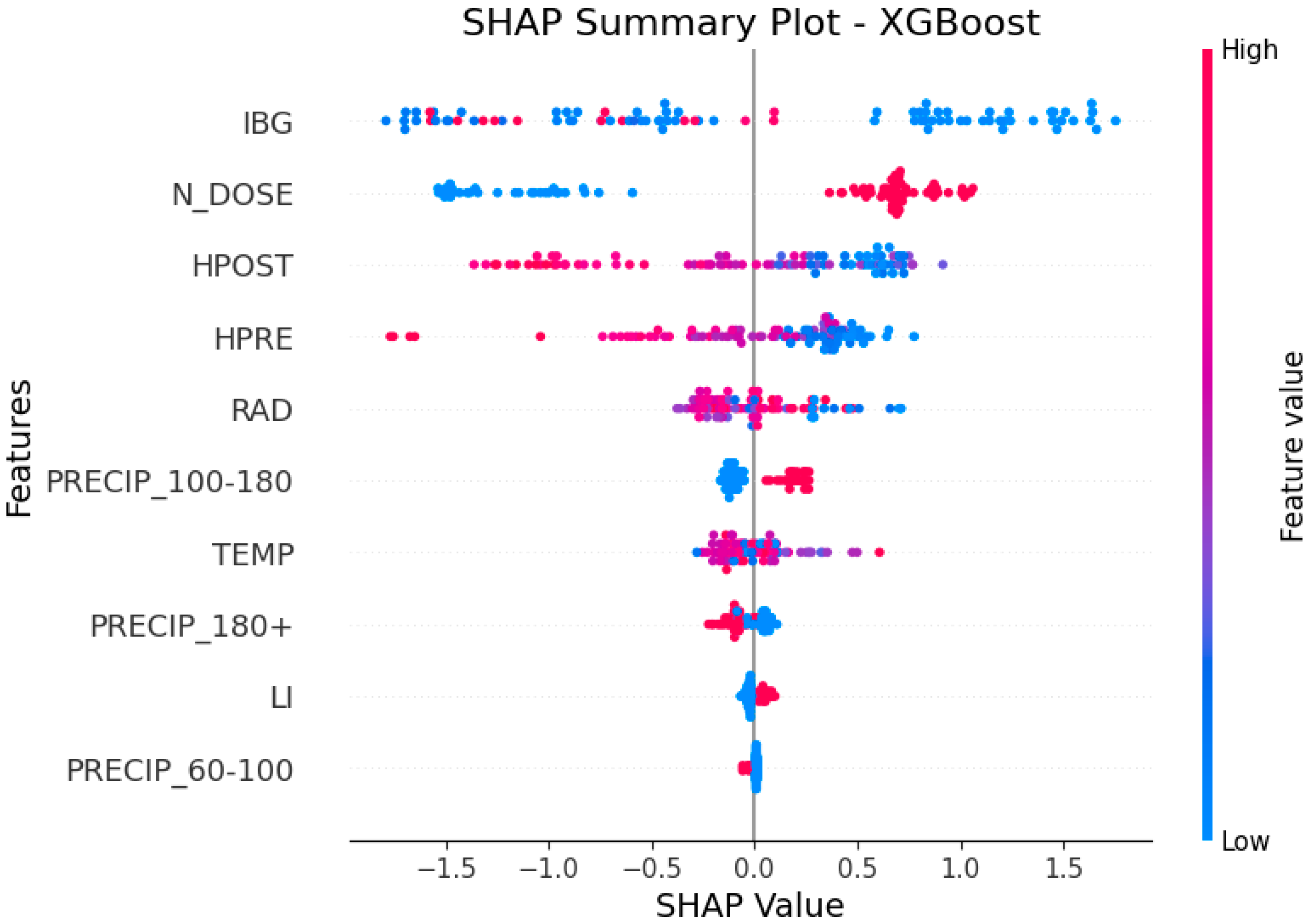

3.3. Answering RQ3: Which Precipitation Range Has Positive SHAP Values in Predicting the CP Content of Tamani Grass?

- When discretized precipitation is in the range of 100–180 mm (PRECIP_100–180 = 1), the SHAP value is positive, indicating that it drives the model toward higher predictions of leaf CP content;

- When precipitation exceeds 180 mm (PRECIP_180+ = 1), the SHAP value is negative, contributing to a decrease in the model’s prediction;

- Precipitation in the range of 60–100 mm (PRECIP_60–100 = 1) and LI have no significant impact on the model (SHAP value ≈ 0) (Figure 5).

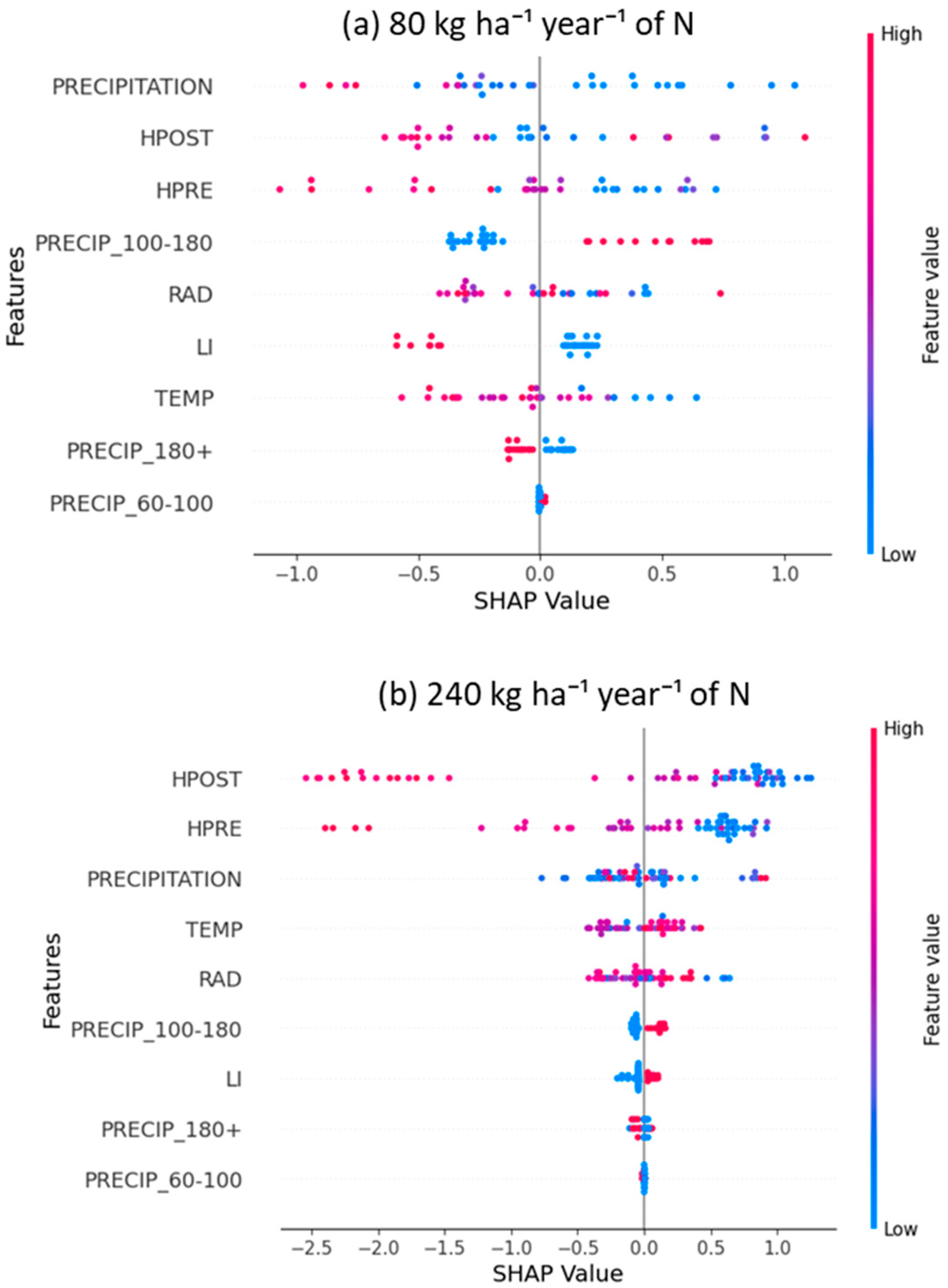

3.4. In Response to RQ4: Does N_DOSE Influence the Hierarchy of Importance of Management and Environmental Variables in Predicting the Crude Protein Content of Tamani Grass Leaves?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wani, S.; Kanth, R.H.; Tantry, R.A. Intensification of Forage Production and Quality Parameters: A Review. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Soc 2022, 40, 513–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.O.; Miotto, F.R.C.; Neiva, J.N.M.; Silva, L.F.F.M.; Freitas, I.B.; Araújo, V.L.; Restle, J. Efeitos do aumento dos níveis de nitrogênio no capim Mombaça em pastagem características, composição química e desempenho da pecuária de corte nos trópicos úmidos da Amazônia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 3293–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyika, J.; Chui, M.; Miremadi, M.; Bughin, J.; George, K.; Willmott, P.; Dewhurst, M. A Future That Works: Automation, Employment, and Productivity; McKinsey Global Institute: Beijing, China, 2017; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/digital-disruption/harnessing-automation-for-a-future-that-works (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Röös, E.; Bajželj, B.; Smith, P.; Patel, M.; Little, D.; Garnett, T. Greedy or needy? Land use and climate impacts of food in 2050 under different livestock futures. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfert, S.; Ge, L.; Verdouw, C.; Bogaardt, M.J. Big data in smart farming—A review. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, I.L.; Valente, D.S.M.; De Oliveira, T.F.; Montagner, D.B.; Euclides, V.P.B.; Chizzotti, F.H.M. Canopy height and biomass prediction in Mombaça guinea grass pastures using satellite imagery and machine learning. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1638–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, I.L.; Valente, D.S.; Silva, F.F.; Chizzotti, M.L.; Paulino, M.F.; D’áUrea, A.P.; Paciullo, D.S.; Pedreira, B.C.; Chizzotti, F.H. Prediction of aboveground biomass and dry—Matter content in Brachiaria pastures by combining meteorological data and satellite imagery. Grass Forage Sci. 2021, 76, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, A.A.; Werner, J.P.S.; Silva, B.C.; Figueiredo, G.K.D.A.; Antunes, J.F.G.; Esquerdo, J.C.D.M.; Coutinho, A.C.; Lamparelli, R.A.C.; Rocha, J.V.; Magalhães, P.S.G. Monitoring pasture aboveground biomass and canopy height in an integrated crop–livestock system using textural information from PlanetScope imagery. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defalque, G.; Santos, R.; Bungenstab, D.; Echeverria, D.; Dias, A.; Defalque, C. Machine learning models for dry matter and biomass estimates on cattle grazing systems. Comput. Electron. 2024, 216, 108520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Han, Q.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Zou, X. YOLO-BLBE: A novel model for identifying blueberry fruits with different maturities using the I-MSRCR method. Agronomy 2024, 14, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpe, C.; Leukel, J.; Zimpel, T. Prediction of pasture yield using machine learning-based optical sensing: A systematic review. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 430–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubo-Robles, D.; Devegowda, D.; Jayaram, V.; Bedle, H.; Marfurt, K.J.; Pranter, M.J. Machine learning model interpretability using SHAP values: Application to a seismic facies classification task. In SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting; SEG: Houston, TX, USA, 2020; p. D021S008R006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/hash/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Abstract.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable. 2020. Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.G.; Lee, S. Consistent individualized feature attribution for tree ensembles. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, R.; Li, X.; Chen, R.; Liu, J. Grazing regime rather than grazing intensity affect the foraging behavior of cattle. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 85, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yan, G.; Li, F.; Lin, H.; Jiao, H.; Han, H.; Liu, W. Optimized Machine Learning Models for Predicting Core Body Temperature in Dairy Cows: Enhancing Accuracy and Interpretability for Practical Livestock Management. Animals 2024, 14, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingler, A.; Dujakovic, A.; Vuolo, F.; Mayer, K.; Gaier, L.; Pötsch, E.M.; Schaumberger, A. Prediction of grassland yield in Austria: A machine learning approach based on satellite, weather, and extensive in situ data. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 170, 127701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, D.; Li, S.; Tang, K.; Yu, H.; Yan, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Xin, X. Comparative Analysis of Feature Importance Algorithms for Grassland Aboveground Biomass and Nutrient Prediction Using Hyperspectral Data. Agriculture 2024, 14, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, V.G.; Batello, C.; Berretta, E.J.; Hodgson, J.; Kothmann, M.; Li, X.; McIvor, J.; Milne, J.; Morris, C.; Peeters, A.; et al. An international terminology for grazing lands and grazing animals. Grass Forage Sci. 2011, 66, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marten, G.C.; Shenk, J.S.; Barton, F.E. Near Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy (NIRS): Analysis of Forage Quality; United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Beltsville, MD, USA, 1985; p. 643. [Google Scholar]

- Tesk, C.R.M.; Pedreira, B.C.; Pereira, D.H.; Pina, D.D.S.; Ramos, T.A.; Mombach, M.A. Impact of grazing management on forage qualitative characteristics: A review. Sci. Electron. Arch. 2018, 11, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenutti, M.A.; Gordon, I.J.; Poppi, D.P.; Crowther, R.; Spinks, W. Foraging mechanics and their outcomes for cattle grazing reproductive tropical swards. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delevatti, L.M.; Romanzini, P.; Fabiano, J.; Koscheck, W.; Luis Da Ross De Araujo, T.; Renesto, D.M.; Ferrari, A.C.; Pavezzi Barbero, R.; Mulliniks, J.T.; Reis, R.A. Forage management intensification and supplementation strategy: Intake and metabolic parameters on beef cattle production. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2019, 247, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euclides, V.P.B.; Montagner, D.B.; de Araújo, A.R.; de Aragão Pereira, M.; dos Santos Difante, G.; de Araújo, I.M.M.; Barbosa, L.F.; Barbosa, R.A.; Gurgel, A.L.C. Biological and economic responses to increasing nitrogen rates in Mombaça guinea grass pastures. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Mlambo, V.; Jennings, P.G.A.; Lallo, C.H.O. The accuracy of predicting in vitro ruminal organic matter digestibility from chemical components of tropical pastures varies with season and harvesting method. Trop. Agric. 2014, 91. Available online: https://journals.sta.uwi.edu/ojs/index.php/ta/article/view/927 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Pereira, L.E.T.; Nishida, N.T.; Carvalho, L.D.R.; Herling, V.R. Recomendações Para Correção e Adubação de Pastagens Tropicais; Faculdade de Zootecnia e Engenharia de Alimentos da USP: Pirassununga, Brazil, 2018; 56p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreira, B.C.; Pereira, L.E.T.; Paiva, A.J. Eficiência produtiva e econômica na utilização de pastagens adubadas. Simpósio Matogrossense Bov. Corte 2013, 2, 2013–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, A.M.Q.; Macedo, V.H.M.; de Oliveira, J.K.S.; Melo, D.d.M.; Domingues, F.N.; Cândido, E.P.; Faturi, C.; Rêgo, A.C.D. Nitrogen fertilisation as a strategy for intensifying production and improving the quality of Massai grass grown in a humid tropical climate. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.C.C.; Montagner, D.B.; Araujo, A.R.; Euclides, V.P.B.; Difante, G.S.; Gurgel, A.L.C.; Souza, D.L. The soil-plant interface in Megathyrsus maximus cv. Mombasa subjected to different doses of nitrogen in rotational grazing. Rev. Mex. Ciências Pecuárias 2021, 12, 1098–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.A.; Paciullo, D.S.C.; Silva, F.F.; Morenz, M.J.F.; Gomide, C.A.M.; Rodrigues, R.A.R.; Bretas, I.L.; Chizzotti, F.H.M. Evaluation of a long-established silvopastoral Brachiaria decumbens system: Plant characteristics and feeding value for cattle. Crop Pasture Sci. 2019, 70, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Cleef, F.O.S.; van Cleef, E.H.C.B.; Longhini, V.Z.; Nascimento, T.S.; Ezequiel, J.M.B.; Ruggieri, A.C. Feedlot performance, carcass characteristics, and meat characteristics of lambs grown under silvopastoral systems. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 100, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, J. Grazing Management: Science into Practice; Logman Group UK Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 1990; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- Sbrissia, A.F.; da Silva, S.C.; Nascimento Júnior, D. Ecofisiologia de plantas forrageiras e o manejo do pastejo. Simpósio Sobre Manejo Pastagem 2007, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevalli, R.A.; Da Silva, S.C.; Bueno, A.D.O.; Uebele, M.C.; Bueno, F.O.; Hodgson, J.; Silva, G.N.; Morais, J.P.G. Herbage production and grazing losses in Panicum maximum cv. Mombaça under four grazing managements. Trop. Grassl. 2006, 40, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Pedreira, B.C.; Pedreira, C.G.S.; Silva, S.C.D. Acúmulo de forragem durante a rebrotação de capim-xaraés submetido a três estratégias de desfolhação. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2009, 38, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant, 2nd ed.; Cornell University 1250 Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| Variable (Symbol) | Meaning | Unit | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20/21 Rainy | season | binary var. (1/0) | [0; 1] |

| 21 Rainy-Dry | season | binary var. (1/0) | [0; 1] |

| 21 Dry-Rainy | season | binary var. (1/0) | [0; 1] |

| 21/22 Rainy | season | binary var. (1/0) | [0; 1] |

| 22 Rainy-Dry | season | binary var. (1/0) | [0; 1] |

| TEMP | average temperature | degrees °C | [22.72; 30.35] |

| RAD | solar radiation | KJ/m2 | [673.79; 2184.90] |

| PREC | precipitation | mm | [0; 1136.4] |

| PRECIP.100–180 | discretized precipitation | mm | [100; 180] |

| PRECIP.180+ | discretized precipitation | mm | [180; 1136.4] |

| PRECIP.60–90 | discretized precipitation | mm | [60; 90] |

| N DOSE | nitrogen dose | kg ha−1 year−1 | [80; 240] |

| LI | light interception | % | [90; 95] |

| IBG | interval between grazing | days | [12; 69] |

| HPRE | pre-grazing height | cm | [24.5; 51] |

| HPOST | post-grazing height | cm | [11; 26] |

| CP | crude protein | % of DM | [6.6; 18.51] |

| Model | Hyperparameters | Interval |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Colsample bytree: 0.6, learning rate: 0.1, max depth: 2, n estimators: 200, reg alpha: 0.6, reg lambda: 2, subsample: 0.6 | Colsample bytree: [0.6, 0.8, 1.0], learning rate: [0.001, 0.01,0.1], max depth: np.arange(2, 8, 2), n estimators: [200, 600,1000], reg alpha: [0, 0.2, 0.6], reg lambda’: [1, 1.5, 2] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monteiro, G.O.d.A.; Difante, G.d.S.; Montagner, D.B.; Euclides, V.P.B.; Castro, M.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Pereira, M.d.G.; Ítavo, L.C.V.; Campos, J.A.; da Costa, A.B.; et al. Interpreting Machine Learning Models with SHAP Values: Application to Crude Protein Prediction in Tamani Grass Pastures. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2780. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122780

Monteiro GOdA, Difante GdS, Montagner DB, Euclides VPB, Castro M, Rodrigues JG, Pereira MdG, Ítavo LCV, Campos JA, da Costa AB, et al. Interpreting Machine Learning Models with SHAP Values: Application to Crude Protein Prediction in Tamani Grass Pastures. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2780. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122780

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonteiro, Gabriela Oliveira de Aquino, Gelson dos Santos Difante, Denise Baptaglin Montagner, Valéria Pacheco Batista Euclides, Marina Castro, Jéssica Gomes Rodrigues, Marislayne de Gusmão Pereira, Luís Carlos Vinhas Ítavo, Jecelen Adriane Campos, Anderson Bessa da Costa, and et al. 2025. "Interpreting Machine Learning Models with SHAP Values: Application to Crude Protein Prediction in Tamani Grass Pastures" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2780. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122780

APA StyleMonteiro, G. O. d. A., Difante, G. d. S., Montagner, D. B., Euclides, V. P. B., Castro, M., Rodrigues, J. G., Pereira, M. d. G., Ítavo, L. C. V., Campos, J. A., da Costa, A. B., & Matsubara, E. T. (2025). Interpreting Machine Learning Models with SHAP Values: Application to Crude Protein Prediction in Tamani Grass Pastures. Agronomy, 15(12), 2780. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122780